Abstract

Research in bone tissue engineering aims to design materials that are effective at generating bone without causing significant side effects. The osteogenic potential of combining matrices and protein growth factors has been well documented, however, improvements are necessary to achieve optimal therapeutic benefits upon clinical translation. In this article, rat calvarial defects were treated with gene-activated matrices (GAMs). The GAMs used were collagen sponges mineralized with a simulated body fluid (SBF) containing a nonviral gene delivery system. Both in vitro and in vivo studies were performed to determine the optimal mode of gene delivery. After 6 weeks, the defects were extracted to assess bone formation and tissue quality through histological and microcomputed tomography analyses. The optimal GAM consisted of a collagen sponge with polyethylenimine plasmid DNA (PEI-pDNA) complexes embedded in a calcium phosphate coating produced by SBF, which increased total bone formation by 39% compared with 19% for control samples. A follow-up in vivo study was performed to optimize the ratio of growth factors included in the GAM. The optimal ratio for supporting bone formation after 6 weeks of implantation was five parts of pBMP-2 to three parts pFGF-2. These studies demonstrated that collagen matrices biomimetically mineralized and activated with plasmids encoding fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) can optimally improve bone regeneration outcomes.

Impact statement

Bone tissue engineering has explored both nonviral gene delivery and the concept of biomimetic mineralization. In this study, we combined these two concepts to further enhance bone regeneration outcomes. We demonstrated that embedding polyethylenimine (PEI)-based gene delivery within a mineral layer formed from simulated body fluid (SBF) immersion can increase bone formation rates. We also demonstrated that the ratio of growth factors utilized for matrix fabrication can impact the amount of bone formed in the defect site. This research highlights a combined approach using SBF and nonviral gene delivery both in vitro and in vivo and prepares the way for future optimization of synthetic gene activated matrices.

Keywords: gene therapy, tissue engineering, polyethylenimine, simulated body fluid, calvarial defect model

Introduction

One goal of bone tissue engineering is to develop materials or composites that adequately repair bone without requiring human tissue grafts. The current gold standard for critical-sized bone defect repair are autografts, but autografts necessitate additional surgery, which leads to pain, surgery-related comorbidities, and increased costs. A suitable synthetic matrix for bone repair requires cellular compatibility, osteoconductivity, and osteoinductivity.1 To this end, simulated body fluid (SBF) has been used to biomimetically coat matrices to increase the bioactivity for bone tissue regeneration.2 Additionally, growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2), can be loaded into matrices to increase osteoinductivity.3–6

SBF is a solution that contains ions in similar concentrations to that present in human blood plasma.7 Traditionally, SBF has been used to evaluate the osteoconductivity of materials by incubating the testing materials in SBF and measuring the mineralization rate of the material's surface.2,8 By the same principle, SBF can also be used to form a calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite (HA) layer on a substrate over time; this process can be accelerated by increasing the concentration of calcium and phosphate ions in the SBF solution.9 The SBF-derived mineralized layer is biocompatible, releases calcium and phosphate ions, and can help facilitate bone synthesis. This concept has been applied previously by incubating a collagen substrate in SBF to improve bone tissue engineering outcomes.3,10

Growth factors are often used in bone tissue engineering to increase vascularization, cell proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation.3,11 Recombinant human proteins, BMP-2 and BMP-7, are currently used in FDA-approved bone graft substitutes to increase bone formation rates, however, these materials do have unwanted side effects.12,13 Due to the short half-life of BMPs necessitating a large initial dose, literature has suggested that the bolus dose of proteins in these bone graft substitutes have disadvantages such as increased risk for edema, and ectopic bone formation.14,15 Gene therapy offers a more desirable release of protein at the target site because gene therapy avoids a rapid release of protein often caused by the initial burst release.16 To deliver the gene therapy, polyethylenimine (PEI) was selected because it is a low-cost nonviral vector that is capable of packaging plasmid DNA (pDNA) for nuclear delivery, even after lyophilization in a collagen matrix.17,18 Additionally, our previous work has demonstrated that PEI-pDNA complexes effectively induce protein expression and bone formation in vivo.4

In this study, pBMP-2 and pFGF-2 were selected to load into the gene-activated matrices (GAMs) because previous works demonstrated that the production of growth factors specific to bone formation was improved when using these two growth factors together.3,19 BMP-2 is a growth factor that induces osteogenic differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), and FGF-2 is a proliferation inducer and has a role in angiogenesis.20 Our previous work has shown that a combined treatment of pFGF-2 and pBMP-2 is more effective at inducing osteogenesis in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and promoting bone repair in diabetic rabbits than either is alone.4,21 However, BMSCs were selected for this work because they are commonly used in tissue engineering approaches and are likely responsible for populating damaged bone tissue.4,22,23 Additionally, research evaluating the order for introducing these growth factors to a bone defect consistently found that FGF-2 followed by BMP-2 delivery produced the best outcomes in terms of improved bone repair.24,25 Therefore, we aimed to deliver plasmids independently encoding for FGF-2 and BMP-2 sequentially by embedding them into two SBF mineralized layers coating the collagen sponges.

Our goal consisted of combining a nonviral gene delivery system with a biomimetic coating deposited by SBF mineralization for bone regeneration, then optimizing the ratios of the pBMP-2 to pFGF-2 within the mineral coating of the GAM to maximize the amount of bone tissue formed. We hypothesized that: (1) combining an SBF coating and, (2) nonviral gene delivery in the coating will further enhance growth factor production in vitro and bone formation in vivo compared with that of a collagen matrix alone. Additionally, the ratio of pBMP-2 to pFGF-2 was optimized in the coating to further increase the amount of bone formed. The first hypothesis was based on our previous findings that increased calcium can improve the transfection efficiency and the expression of PEI-pDNA complexes.26 In this study, PEI-pDNA complexes were prepared encoding for BMP-2 and FGF-2 and coprecipitated within the SBF coating. The prepared matrices were then tested both in vitro and in vivo for bone regeneration outcomes. Herein, we show that the combination of SBF with nonviral gene delivery can enhance bone tissue regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Concentrated SBF preparation

A 3.5 × SBF solution was prepared similarly to a 1.00 × solution as described in a previous publication.27 The original 1.00 × SBF solution consists of 141 mM Na+, 5 mM K+, 1.5 mM Mg2+, 2.5 mM Ca2+, 152 mM Cl−, 4.2 mM HCO3−, 1.0 mM H2PO4−, and 0.5 mM SO4− in water adjusted to pH 7.4 with Tris-HCl. For the work presented here, a more concentrated form of SBF (3.5 × SBF) was prepared. The concentrations of CaCl2 and KH2PO4- were increased to 8.75 and 3.5 mM, respectively, and the pH was adjusted to 6.3 with Tris-HCl to increase the solubility; all other ion concentrations remained the same. The listed salts were added individually to nanopure water at 37°C. The solution was then sterile filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and stored at 4°C for future use.

PEI-pDNA fabrication

PEI-pDNA complexes were prepared based on previous work.28 Branched PEI, molecular weight 25,000 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) was combined with pDNA based on molar ratios of the amine groups in the PEI (N) to the phosphate groups in the pDNA (P) at an N/P ratio of 10:1. Then 50 μg of pDNA was added to 500 μL of sterile Nanopure water, and 32.57 μg of PEI was diluted into a separate aliquot of 500 μL of sterile Nanopure water. These two solutions were combined and vortexed for 30 s at 2,500 rpm. The PEI-pDNA complexes were stabilized by incubating them for 30 min at room temperature before use. The pDNA contained one gene sequence encoding for EGFP (pEGFP), FGF-2 (pFGF-2), or BMP-2 (pBMP-2). pEGFP was a gift from Doug Golenbock (plasmid No. 13031 open read frame [ORF] ref LC337019.1; Addgene, Watertown, MA) and the pFGF-2 and pBMP-2 were purchased from OriGene (Rockville, MD; FGF-2 plasmid No. SC118884 ORF ref NM_002006.3, BMP-2 plasmid No. SC119392 ORF ref NM_001200.1). All plasmids utilized a CMV promotor and were untagged; the plasmid containing EGFP was codon optimized. The pDNAs were transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α and then harvested using the Endotoxin-Free Plasmid Maxiprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Matrix fabrication and characterization

Collagen sponges, Collaplugs (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN), were aseptically cut into disks (10 mm diameter × 2 mm height) with a scalpel blade. For matrices that were not SBF mineralized, the collagen sponge was stored frozen after cutting. To incorporate PEI-pDNA complexes into the collagen sponges, a solution containing 50 μg/mL of complexes based on the weight of pDNA was pipetted directly into the center of the collagen sponge in 100 μL increments.26 Then the collagen sponge was frozen and lyophilized. This process was repeated until the desired amount of complexes had been added to the collagen sponge.

For SBF mineralized matrices, the cut disks were placed into 24-well plates and incubated with 1 mL of 3.5 × SBF. Every 24 h the SBF solution was refreshed. The mineralization was carried out for 30 days. The matrix with complexes embedded was prepared as follows: 10 days of SBF mineralization, 5 days of SBF mineralization with PEI-pBMP-2 complexes at 5 μg/mL, 5 days of SBF mineralization, 5 days of SBF mineralization with PEI-pFGF-2 complexes at 5 μg/mL, and 5 days of SBF mineralization for a total of 30 days. In other words, the matrices with PEI-pDNA complexes were exposed to 25 μg of PEI-pDNA complexes total over a 5-day period or 5 μg per day. After the mineralization process, the matrices were frozen at −20°C and lyophilized. For the first animal study, each defect received a full matrix; for the second animal study, the matrices were bisected to better fit inside of the defect.

To visualize the layers formed during coincubation of PEI-pDNA complexes in the SBF solution, PEI-pDNA complexes formed from PEI conjugated to either Tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) or Fluorescein-5-Isothiocyanate (FITC; Thermo Fisher) were used. To form the layers, collagen matrices were first incubated in SBF for 10 days, followed by coincubation of SBF and PEI-pDNA complexes labeled with TRITC at 1 μg/day for 5 days. Then, the matrices were treated with 5 days of SBF mineralization, followed by the final coincubation of SBF and PEI-pDNA complexes labeled with FITC at 1 μg/day for 5 days. Matrices containing the labeled PEI-pDNA complexes were visualized in three dimensions using a Leica SP8 STED confocal microscope (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Collagen matrices alone and collagen matrices mineralized with SBF for 30 days were mounted on scanning electron microscopy (SEM) stubs and sputter coated with Au-Pd (Emitech K550 Sputter Coater, Kent, England, United Kingdom). The samples were then visualized using an S-4800 SEM (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The acceleration voltage and the current were 1.5 kV and 10 μA, respectively. The calcium phosphate coating from a 20-day mineralized matrix was analyzed using an energy-dispersive spectroscope, Model 550i (IXRF Systems, Austin, TX).

Human BMSC culture

Primary human adult BMSCs (No. PCS-500-012; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were subcultured for at least two passages before beginning experiments. The BMSCs were cultured in complete media: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), low glucose, l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 1 × GlutaMAX, and 50 μg/mL gentamicin sulfate (Thermo Fisher). The cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Cells were passaged every 7 days or upon reaching 90% confluence.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

BMSCs were seeded at 50,000 cells/well in 24-well tissue culture plates in complete medium. After 24 h, the medium was changed to FBS-free medium, and the BMSCs were transfected with indicated PEI-pDNA complexes as shown in Table 1. After the transfection, the cells were washed with PBS, and 0.5 mL of complete medium was added to each well. The cells were cultured for 48 h. A 10 mg/mL solution of heparin in sterile water was added to bring the concentration of heparin to 10 μg/mL in each well. This was to ensure the complete release of surface-bound proteins from the cells. After 4 h, the supernatants were collected and analyzed using the Human FGF-2 Basic Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kit and the BMP-2 Quantikine ELISA Kit (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MI) using the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 1.

Scheme of Polyethylenimine/Plasmid DNA Complexes Added to Each Group

| Groups |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Empty vector | BMP-2 | BMP-2+FGF-2 3:1 | BMP-2+FGF-2 3:2 | BMP-2+FGF-2 3:3 | |

| Complexes (μg) | ||||||

| PEI-pEGFP | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| PEI-pBMP-2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| PEI-pFGF-2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 1.00 |

| Total PEI-pDNA | 0.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

BMP-2, bone morphogenetic protein-2; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; pDNA, plasmid DNA; PEI, polyethylenimine.

Calvarial defect model

The animal studies were performed with approval from the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Fisher 344 rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) at 14 weeks of age were used for this study. All animals were housed in animal care facilities and cared for according to the guidelines established by the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol No. 6111900). Before the survival surgeries, the animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine/xylazine solution, 95 and 13.5 mg/kg, respectively. Meloxicam (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany) was also administered before beginning the surgery. To gain access to the calvaria, incisions were made through the skin and periosteum, and the anchoring tissue was separated using a flat blade. On either side of the sagittal suture, a 5 mm diameter defect was created in the calvaria using a round 330 carbide burr. The matrix was implanted, and the periosteum was sutured over the matrix to minimize the movement. After 6 weeks, the animals were euthanized, and the defects were extracted and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histology and microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) analyses.

To test the efficacy of SBF mineralization, five groups were examined as follows: uncoated collagen matrix (Collagen; N = 3); SBF mineralized matrix (SBF; N = 4); uncoated collagen matrix loaded with 25 μg of both PEI-pBMP-2 and PEI-pFGF-2 complexes (Collagen GAM; N = 4); SBF mineralized matrix loaded with PEI-pDNA complexes (SBF GAM; N = 4); and SBF mineralized matrix with PEI-pDNA complexes embedded (SBF GAM embedded; N = 4).

For the optimization of the pFGF-2 to pBMP-2 ratio, five groups were examined as follows: SBF mineralized matrix (SBF; N = 6); SBF mineralized matrix with 12.5 μg of PEI-pBMP-2 complexes embedded (BMP-2; N = 4); SBF mineralized matrix with 12.5 μg of PEI-pBMP-2 and 2.5 μg of PEI-pFGF-2 complexes embedded (BMP-2+FGF-2 5:1; N = 5); SBF mineralized matrix with 12.5 μg of PEI-pBMP-2 and 7.5 μg of PEI-pFGF-2 complexes embedded (BMP-2+FGF-2 5:3; N = 5); SBF mineralized matrix with 12.5 μg of PEI-pBMP-2 and 12.5 μg of PEI-pFGF-2 complexes embedded (BMP-2+FGF-2 5:5; N = 5); and SBF mineralized matrix with PEI-pDNA complexes embedded. All groups with PEI-pDNA complexes contained the same amount of PEI to minimize effects due to PEI.

Micro-CT and histology staining

A Skyscan 1272, a high-resolution X-ray microtomograph (Bruker, Billerica, MA), at 100 kV·μA was used to scan the defects with a voxel size of 21.7 μm3. Bone tissue was identified based on a density threshold, and bone volume per total volume was calculated using Dragon Fly analysis software (Object Research Systems, Quebec, Canada).

After micro-CT analysis, the samples were incubated in Surgipath decalcifier solution (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) for 2 weeks, and the solution was replaced every 2 days. The solution was assessed for calcium concentration by adding ammonium oxalate to an aliquot of the used decalcifier solution. The tissue was determined to be fully decalcified when no precipitates formed when the ammonium oxalate was added to the supernatant. The decalcified tissue was paraffin embedded, microtomed, mounted, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin. Each defect was bisected, so the tissue slice ran through the center of the defect in question. The bright-field images were captured using a bright-field microscope (Olympus BX61) equipped with a digital camera (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed with a sample size of at least 3. For statistical testing, one-way or two-way analysis of variance was performed for all datasets containing more than two groups; otherwise, a student's t-test was performed. If significance was detected, a Dunnett's test was performed to identify the experimental groups that were significantly different from the empty defect group. All data are represented as mean of the samples, and the error bars represent standard deviation.

Results

GAMs mineralized in SBF were characterized for surface morphology and chemical composition

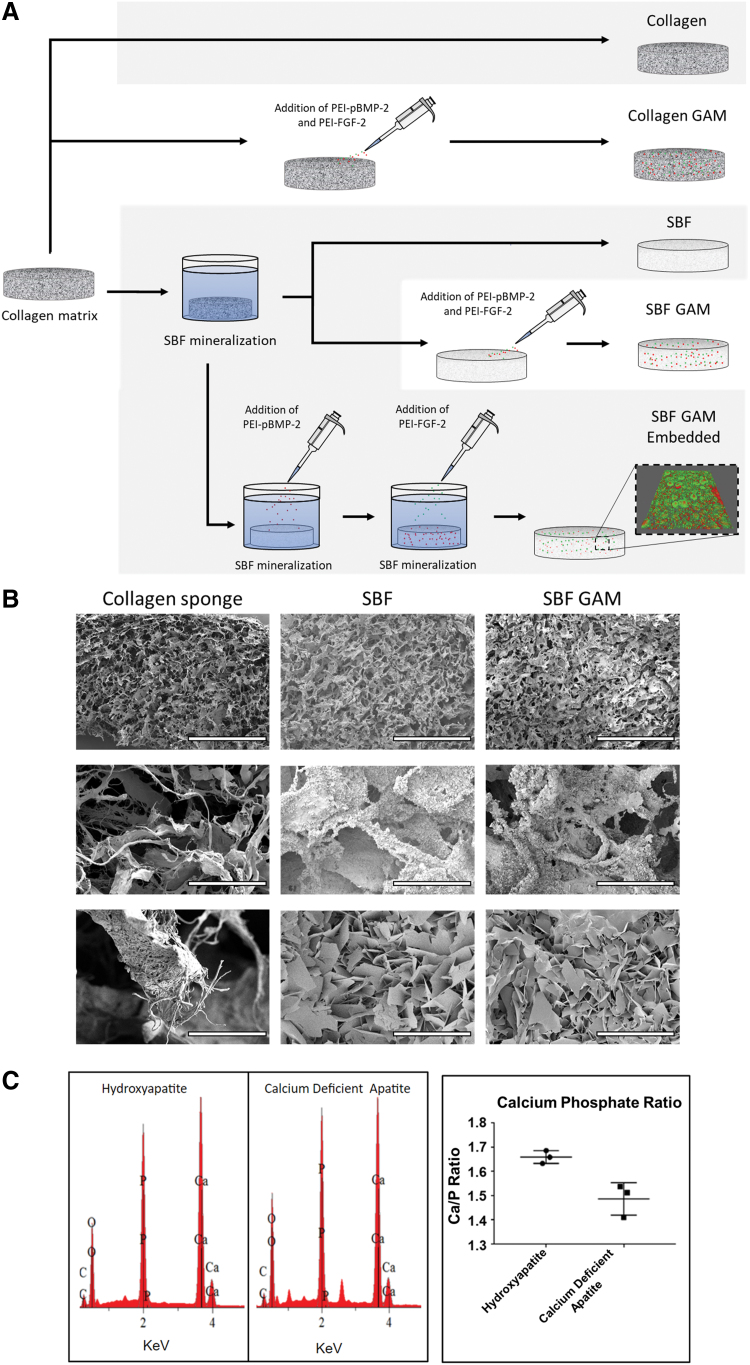

The fabrication strategy for the five types of matrices examined for this study uses a combination of PEI-pDNA complexes, SBF solution, and collagen matrices (Fig. 1A). Collagen matrices were either used as is (Collagen) or injected with PEI-pFGF-2 and PEI-pBMP-2 complexes (Collagen GAM). For the SBF mineralized matrices, collagen matrices were mineralized first (SBF) and subsequently injected with a solution containing PEI-pFGF-2 and PEI-pBMP-2 complexes (SBF GAM). For the final group (SBF GAM Embedded), the collagen matrices were mineralized for 10 days, followed by a coincubation of PEI-pBMP-2 complexes in SBF, then PEI-pFGF-2 complexes. This created a bilayer system within the mineral coat containing PEI-pFGF-2 (green) in the outer layer with PEI-pBMP-2 (red) in the inner layer. Collagen sponges were mineralized with and without PEI-pDNA complexes and evaluated with SEM (Fig. 1B). The SEM images revealed that SBF incubation formed plate-like crystal structures on the surface of the collagen sponge. The elemental analyses demonstrated the mineral plates formed on the collagen were likely calcium-deficient HA based on the Ca/P ratio of 1.5 as compared with commercial-grade HA, which has a Ca/P ratio of 1.67 (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of SBF mineralized matrices. Matrix fabrication schematic demonstrating the bilayer formed through SBF mineralization with PEI-pDNA complexes. The confocal image is an SBF mineralized 2D surface contain PEI-pDNA complexes dyed with TRITC (red) or FITC (green) (A). SEM images of a collagen sponge, a collagen sponge after 30 days of SBF incubation (SBF), and SBF with PEI-pDNA complexes incorporated (SBF GAM). Under high magnification plate-like structures are visible on the surface of the SBF and SBF GAM groups (B) (scale bars are 1 mm [top] and 100 μm [middle] and 10 μm [bottom]). Element composition of the SBF coating (CDA) by EDS analysis compared with 99.8% pure HA (C). CDA, calcium-deficient apatite; EDS, energy-dispersive spectroscope; FITC, fluorescein-5-Isothiocyanate; GAM, gene-activated matrix; HA, hydroxyapatite; pDNA, plasmid DNA; PEI, polyethylenimine; SBF, simulated body fluid; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; TRITC, tetramethylrhodamine. Color images are available online.

Effect of PEI-pDNA treatment on production of BMP-2 and FGF-2 in vitro

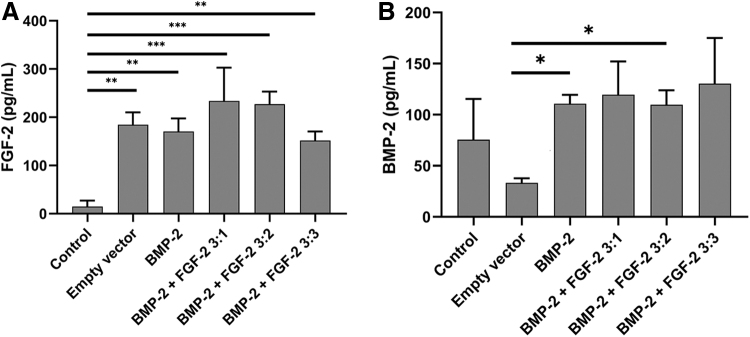

ELISA assays for BMP-2 and FGF-2 were performed on the supernatant from 2-day cultures of BMSCs with various PEI-pFGF-2 and PEI-pBMP-2 concentrations. BMSCs cultured with PEI-pDNA encoding no growth factors (empty vector) produced <200 pg/mL of FGF-2 (Fig. 2A). The BMSCs treated with a ratio of 3:1 BMP-2 to FGF-2 produced the most FGF-2 protein with the ratio of 3:2 being nearly identical. The addition of more PEI-pFGF-2 (i.e., a ratio of 3:3 BMP-2 to FGF-2) did not result in increased FGF-2 secretion. For BMP-2 expression, the control cells produced a basal level of BMP-2 around 70 pg/mL. With the addition of an empty vector, there was a decrease in protein secretion compared with untreated cells, which was likely due to toxic effects of the PEI-pDNA complexes reducing cell viability (Fig. 2B). The groups treated with PEI-pBMP-2 all expressed similar levels of BMP-2 protein (∼110 pg/mL). This suggests that the addition of PEI-pBMP-2 enhances the secretion of BMP-2, however PEI-pFGF-2 had minimal effects on increasing the BMP-2 secretion.

FIG. 2.

ELISA analysis of BMP-2 and FGF-2 production after PEI-pDNA treatment. BMSCs were treated for 4 h with PEI-pDNA complexes either encoding for EGFP (empty vector), BMP-2 (BMP-2), or a ratio of pBMP-2 to pFGF-2 (BMP-2+FGF-2 3:X). All samples were treated with 2 μg of PEI-pDNA complexes total. All groups treated with complexes increased expression of FGF-2 especially those with a ratio of 3:1 or 3:2 PEI-pBMP-2 to PEI-pFGF-2 (A). For BMP-2 expression, the groups BMP-2 and BMP-2 + FGF-2 3:1 secreted significantly more BMP-2 than the empty vector group (B) (N = 3; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005). BMP-2, bone morphogenetic protein-2; BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FGF, fibroblast growth factor.

Effect of matrix design on bone formation in vivo

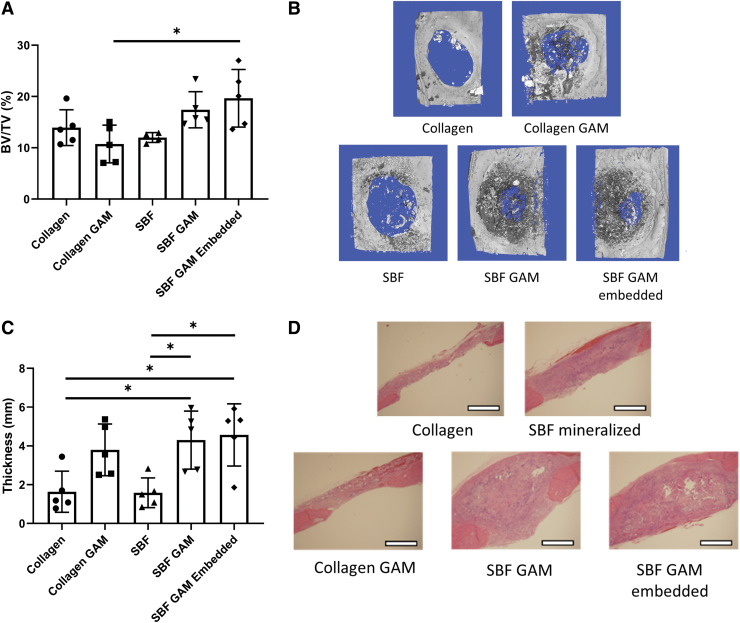

Calvarial defects, 5 mm in diameter, were filled by the various matrices and allowed to heal for 6 weeks (Fig. 3). The results from the micro-CT analysis suggests that the SBF GAM-embedded group had the greatest amount of new bone tissue, and while SBF GAM produced comparable amounts of bone, this was not significantly different from the Collagen GAM group (p = 0.06) (Fig. 3A, B). The SBF mineralization alone did not enhance the amount of new bone tissue at the defect site. The histological analysis demonstrated that significantly more total tissue was formed in the defects with PEI-pDNA present than with collagen present (Fig. 3C, D). These results suggest that PEI-pDNA complexes are effective in facilitating tissue growth at the defect site, but significantly enhanced bone formation was limited to only the SBF GAM-embedded group.

FIG. 3.

Effect of GAM synthesis strategies on bone formation tested in calvarial defect model. Rat calvarial defects assessed by micro-CT and H&E staining. Matrices of collagen (Collagen), SBF mineralized collagen (SBF), collagen loaded with 25 μg of both PEI-pBMP-2 and PEI-pFGF-2 (Collagen GAM), mineralized collagen loaded with the same amounts of PEI-pDNA (SBF GAM), and mineralized collagen with PEI-pDNA embedded (SBF GAM Embedded) were used (A). Micro-CT images of the calvarial defects (B). The thickness of the defects was measured as an indicator of total tissue formation at 6 weeks postsurgery (C). Histology of the bisected extracted calvarial defects (D). (N = as shown; *p < 0.05; scale bar = 1 mm). H&E, Hematoxylin and Eosin; micro-CT, microcomputed tomography. Color images are available online.

Effect of PEI-pBMP-2 to PEI-pFGF-2 ratio on bone formation in vivo

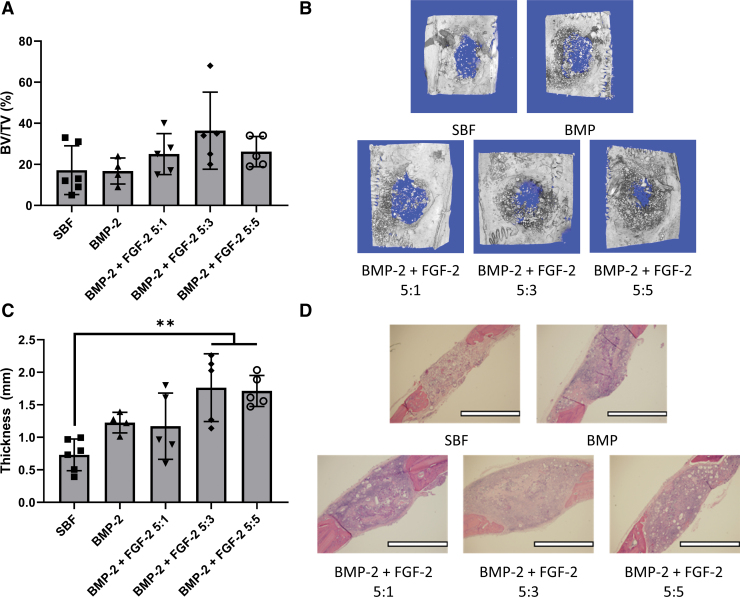

In the second animal study, the goal was to optimize the ratio of PEI-pBMP-2 to PEI-pFGF-2. Each matrix with BMP-2 contained 12.5 μg of PEI-pBMP-2 and the amount of PEI-pFGF-2 contained was either 0, 2.5, 7.5, or 12.5 μg. From the micro-CT data, the BMP-2 + FGF-2 5:3 performed the best in terms of the total amount of new bone tissue in the defect, and the inclusion of PEI-pFGF-2 complexes helped in all groups (Fig. 4A, B). The histology results again suggest that the addition of PEI-pDNA complexes improved the amount of tissue formed throughout the defect (Fig. 4C, D). The BMP-2 + FGF-2 5:3 and BMP-2 + FGF-2 5:5 groups had the highest amount of tissue formed overall at ∼1.7 mm in thickness compared with 0.7 mm in the SBF group.

FIG. 4.

Effect of PEI-pBMP-2 to PEI-pFGF-2 ratio on bone formation tested in calvarial defect model. Rat calvarial defects were generated bilaterally with a diameter of 5 mm and the respective matrices were implanted and allowed to heal for 6 weeks. Matrices of SBF, SBF loaded with 12.5 μg of PEI-pBMP-2, and 12.5 μg of PEI (BMP), SBF loaded with 12.5 μg of PEI-pBMP-2, Y μg of PEI-pFGF-2, and 12.5-Y μg of PEI to give the described ratio (BMP-2 + FGF-2 5:X) were implanted and evaluated with micro-CT (A). Micro-CT images of the calvarial defects (B). The thickness of the defects was measured as an indicator of total tissue formation at 6 weeks postsurgery (C). Histology of the bisected extracted calvarial defects (D). (N = as shown; **p < 0.01; scale bar = 2 mm). Color images are available online.

Discussion

Based on our review of the literature, this is the first study to investigate using nonviral gene delivery in a collagen sponge mineralized in SBF. By controlling the ion content of the SBF, different calcium phosphate mineral compositions and morphologies can be produced.27,29,30 The mineralization rate of SBF solutions increases with higher concentrations of calcium and phosphate and the resulting coatings have a lower Ca/P ratio. Additionally, the SBF composition can affect the morphology of the calcium phosphate crystal structures.29,30 One study examined the effects of changing both calcium and phosphate concentrations in the SBF and found that various morphologies could be produced: spherulitic with 1 × SBF, plate-like with 3.5 × SBF, and net-like with 5 × SBF.29 They found that increasing calcium and phosphate concentrations increased human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation toward the osteoblast lineage, but a decrease in the proliferation rate was evident. Another study compared SBF with and without the addition of carbonate.30 The addition of carbonate produced spherulitic-like structures, whereas the SBF alone produced plate-like structures similar to those depicted in Figure 1C. In that study, the viability of MC3T3s was greater for plate-like structures. In this study, a 3.5 × SBF was selected because it produced a plate-like morphology on the collagen substrate and was the highest concentration of SBF that was consistently produced without precipitation issues. Since the collagen is not an ideal substrate for mineral formation, SBF incubation required an upward of 30 days to achieve a substantial mineral coating, however, polymeric matrices could be used in the future to accelerate the rate of mineralization due to increased concentration of nucleation sites.28

Two important considerations when using multiple growth factors to promote bone tissue engineering are the introduction timeline and the concentrations used. Kuhn et al. found that there were optimal concentrations of rhBMP-2 and rhFGF-2 that promoted maximal osteogenic differentiation in mouse MSCs in vitro.5 Their work noted that a combination of rhBMP-2 with lower amount of rhFGF-2 was optimal for bone formation. Another study specifically investigated the ratios of rhBMP-2 to rhFGF-2 and found that a 2:1 ratio of rhBMP-2 (100 ng/mL) to rhFGF-2 (50 ng/mL) gave the best results in terms of BMSC differentiation and bone formation in an in vivo subcutaneous model.6 In this study, BMSCs were treated with PEI-pDNA complexes instead of with proteins and a focus was the optimization of the ratio of PEI-pBMP-2 to PEI-pFGF-2. The group that secreted the most BMP-2 and FGF-2 protein was treated with a pBMP-2 to pFGF-2 ratio of 3:1, and the group treated with a ratio 3:2 also produced similar results. Although this is with a gene-based therapy, it is consistent with the previously mentioned reports, where a greater introduction of BMP-2 to FGF-2 is advantageous for bone tissue engineering outcomes. Also, of note the PEI-pEGFP was enough to stimulate FGF-2 production despite not encoding a gene related to FGF-2 production. This could be due to cell stress triggered by the PEI causing an upregulation in FGF-2 expression, but further studies would be necessary to confirm this speculation.31,32

This study is the first work to evaluate a SBF-mineralized GAM using PEI-pFGF-2 and PEI-pBMP-2 complexes either surface bound or coprecipitated into layers. The results suggest that the combination of PEI-pDNA complexes embedded in a mineralized matrix improves the amount of bone formed likely due to improved efficacy of the PEI-pDNA complexes. This result is consistent with previous reports that demonstrated transfection improved in the presence of soluble calcium or with a mineralized cell/substrate.26,29 For example, Luong et al. demonstrated pDNA complexes coprecipitated in the mineral layer improved transfection efficiency in vitro, which may have explained the minor increase in the bone formation in the coprecipitated group over the adsorbed group.33

Fine-tuning the ratio of BMP-2 to FGF-2 is crucial for optimal osteogenesis as discussed previously, and optimization of the ratio was required in vivo since gene delivery does not necessarily translate to protein production. Prior research found that a relatively lower dose of FGF-2 when combined with BMP-2 was optimal for promoting osteogenesis.34 However, these results were also based on bolus doses of proteins. With gene delivery, the secretion of the protein is dependent on protein synthesis in the cells and requires time for production. Therefore, the goal of this study was to find an optimal ratio of pBMP-2 to pFGF-2 to load into the matrices. Although there were not significant differences between the different concentrations of pFGF-2 loaded into the matrices, there was a slight trend indicating that the BMP-2 + FGF-2 5:3 group was optimal. From the in vitro results, PEI-pDNA alone stimulated FGF-2 production, so a more efficient gene delivery system such as chemically modified RNA may be required to tease out significant differences.

Conclusions

Both nonviral gene delivery and SBF have been used individually for bone tissue engineering, and the work presented here combines these two approaches to create an optimized matrix. After 20 days of incubating in SBF, a mineralized layer was formed on the collagen sponge surface, and it was demonstrated that the mineral coating could contain layers of PEI-pDNA complexes. BMSCs produced more FGF-2 when exposed to PEI-pDNA complexes. When the matrices were implanted in vivo, the gene delivery system embedded in the calcium phosphate matrix produced the most amount of bone and tissue thickness in the defect. This concept was then further tested by adjusting the ratio of PEI-pBMP-2 to PEI-pFGF-2 complexes embedded in the matrices. The BMP-2 + FGF-2 5:3 group produced more bone and tissue at the defect site than did the SBF group. The results here suggest that SBF mineral coatings for bone tissue engineering can be improved with the incorporation of a nonviral delivery system.

In the future, further analysis of the SBF-mineralized GAMs and experimenting with other materials may provide valuable insights for developing novel matrices for bone tissue engineering. The GAMs described in this study, should be assessed through in vitro biochemical assays to determine the impact on gene expression and the extent of osteodifferentiation. This would help guide future research in making informed decisions on how to improve these matrices. However, some other options to improve these GAMs would be in changing the base material and the nonviral gene delivery method. Using materials such as synthetic polymers and metals instead of a collagen sponge may increase the mechanical properties of the matrix while still retaining the ability to be coated with a gene-activated mineral capable of enhancing bone repair.35 Further improvement to this system may come from using chemically modified RNA instead of PEI-pDNA, since our group has previously demonstrated that incorporation of chemically modified RNA into collagen matrices promotes significantly increased bone healing compared with PEI-pDNA.23 Thus, incorporating chemically modified RNA within the mineral coating may also improve the effectiveness of these matrices.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Liu Hong in the Department of Prosthodontics at the University of Iowa College of Dentistry and Dental Clinics for providing T.M.A., N.Z.L., and L.R.J. with the surgical training on the calvarial defect animal model that has been used in this study.

Authors' Contributions

K.S. and A.K.S. conceived the original experiments for this study. T.M.A., N.Z.L., L.R.J., K.S., and A.K.S. designed, finalized, and carried out the experiments. T.M.A., N.Z.L., and L.R.J., either assisted with or performed the animal surgeries. D.K.M. aided with histological analysis. T.M.A. performed all data analysis, in vitro experiments, and wrote the article. All authors, especially K.S. and A.K.S., provided a critical review of the article. All authors gave final approval of the current version to be published.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This research was supported by the Martin “Bud” Schulman Postdoctoral Fellowship Award from the American Association of Orthodontists Foundation (AAOF).

References

- 1.Amini, A.R., Laurencin, C.T., and Nukavarapu, S.P.. Bone tissue engineering: recent advances and challenges. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 40,363, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin, K., Acri, T., Geary, S., and Salem, A.K.. Biomimetic mineralization of biomaterials using simulated body fluids for bone tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Tissue Eng Part A 23,1169, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gronowicz, G., Jacobs, E., Peng, T., et al. Calvarial bone regeneration is enhanced by sequential delivery of FGF-2 and BMP-2 from layer-by-layer coatings with a biomimetic calcium phosphate barrier layer. Tissue Eng Part A 23,1490, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khorsand, B., Nicholson, N., Do, A.-V., et al. Regeneration of bone using nanoplex delivery of FGF-2 and BMP-2 genes in diaphyseal long bone radial defects in a diabetic rabbit model. J Control Release 248,53, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhn, L.T., Ou, G., Charles, L., et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 and bone morphogenetic protein-2 have a synergistic stimulatory effect on bone formation in cell cultures from elderly mouse and human bone. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68,1170, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang, L., Huang, Y., Pan, K., Jiang, X., and Liu, C.. Osteogenic responses to different concentrations/ratios of BMP-2 and bFGF in bone formation. Ann Biomed Eng 38,77, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokubo, T., Kushitani, H., Sakka, S., Kitsugi, T., and Yamamuro, T.. Solutions able to reproduce in vivo surface-structure changes in bioactive glass-ceramic A-W3. J Biomed Mater Res A 24,721, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kokubo, T., and Takadama, H.. How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials 27, 2907, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richbourg, N.R., Peppas, N.A., and Sikavitsas, V.I.. Tuning the biomimetic behavior of scaffolds for regenerative medicine through surface modifications. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 13,1275, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Munajjed, A.A., Plunkett, N.A., Gleeson, J.P., et al. Development of a biomimetic collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffold for bone tissue engineering using a SBF immersion technique. J Biomed Mater Res B 90B,584, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Witte, T.-M., Fratila-Apachitei, L.E., Zadpoor, A.A., and Peppas, N.A.. Bone tissue engineering via growth factor delivery: from scaffolds to complex matrices. Regen Biomater 5,197, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carragee, E.J., Hurwitz, E.L., and Weiner, B.K.. A critical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 trials in spinal surgery: emerging safety concerns and lessons learned. Spine J 11,471, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James, A.W., LaChaud, G., Shen, J., et al. A review of the clinical side effects of bone morphogenetic protein-2. Tissue Eng Part B 22,284, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly, M.P., Savage, J.W., Bentzen, S.M., et al. Cancer risk from bone morphogenetic protein exposure in spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 96,1417, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter, J.R., Ruckh, T.T., and Popat, K.C.. Bone tissue engineering: a review in bone biomimetics and drug delivery strategies. Biotechnol Prog 25,1539, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park, S.-Y., Kim, K.-H., Kim, S., Lee, Y.-M., and Seol, Y.-J.. BMP-2 gene delivery-based bone regeneration in dentistry. Pharmaceutics 11,393, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, Y.C., Riddle, K., Rice, K.G., and Mooney, D.J.. Long-term in vivo gene expression via delivery of PEI-DNA condensates from porous polymer scaffolds. Hum Gene Ther 16,609, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scherer, F., Schillinger, U., Putz, U., Stemberger, A., and Plank, C.. Nonviral vector loaded collagen sponges for sustained gene delivery in vitro and in vivo. J Gene Med 4,634, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura, Y., Tensho, K., Nakaya, H., et al. Low dose fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) enhances bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2)-induced ectopic bone formation in mice. Bone 36,399, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Mello, S., Elangovan, S., and Salem, A.K.. FGF2 gene activated matrices promote proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells. Arch Oral Biol 60,1742, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atluri, K., Seabold, D., Hong, L., Elangovan, S., and Salem, A.K.. Nanoplex-mediated codelivery of fibroblast growth factor and bone morphogenetic protein genes promotes osteogenesis in human adipocyte-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Pharm 12,3032, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colnot, C.Cell sources for bone tissue engineering: insights from basic science. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 17,449, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elangovan, S., Khorsand, B., Do, A.-V., et al. Chemically modified RNA activated matrices enhance bone regeneration. J Control Release 218,22, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei, L., Wang, S., Wu, H., et al. Optimization of release pattern of FGF-2 and BMP-2 for osteogenic differentiation of low-population density hMSCs. J Biomed Mater Res A 103,252, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, S., Ju, W., Shang, P., Lei, L., and Nie, H.. Core–shell microspheres delivering FGF-2 and BMP-2 in different release patterns for bone regeneration. J Mater Chem B 3,1907, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acri, T.M., Laird, N.Z., Geary, S.M., Salem, A.K., and Shin, K.. Effects of calcium concentration on nonviral gene delivery to bone marrow-derived stem cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 13,2256, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin, K., Jayasuriya, A.C., and Kohn, D.H.. Effect of ionic activity products on the structure and composition of mineral self assembled on three-dimensional poly(lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A 83,1076, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elangovan, S., D'Mello, S.R., Hong, L., et al. The enhancement of bone regeneration by gene activated matrix encoding for platelet derived growth factor. Biomaterials 35,737, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi, S., and Murphy, W.L.. A screening approach reveals the influence of mineral coating morphology on human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Biotechnol J 8,496, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lebourg, M., Suay Antón, J., and Gomez Ribelles, J.L.. Characterization of calcium phosphate layers grown on polycaprolactone for tissue engineering purposes. Compos Sci Technol 70,1796, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beyerle, A., Irmler, M., Beckers, J., Kissel, T., and Stoeger, T.. Toxicity pathway focused gene expression profiling of PEI-based polymers for pulmonary applications. Mol Pharm 7,727, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zittermann, S.I., and Issekutz, A.C.. Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, FGF-2) potentiates leukocyte recruitment to inflammation by enhancing endothelial adhesion molecule expression. Am J Pathol 168,835, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luong, L.N., McFalls, K.M., and Kohn, D.H.. Gene delivery via DNA incorporation within a biomimetic apatite coating. Biomaterials 30,6996, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charles, L.F., Woodman, J.L., Ueno, D., et al. Effects of low dose FGF-2 and BMP-2 on healing of calvarial defects in old mice. Exp Gerontol 64,62, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qian, Y., Chen, H., Xu, Y., et al. The preosteoblast response of electrospinning PLGA/PCL nanofibers: effects of biomimetic architecture and collagen I. Int J Nanomedicine 11,4157, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]