Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to compare pre/post-COVID-19 changes in mental health–related emergency department visits among adolescents.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of all mental health–related emergency department visits in two large tertiary pediatric hospital centers between January 2018 and December 2020. We described monthly pre/post-COVID-19 changes in frequency and proportion of mental health visits as well as changes in hospitalization rates for eating disorders, suicidality, substance use, and other mental health conditions.

Results

We found an increase in the proportion of mental health–related emergency department visits during the months of July–December 2020 (p < .01). There was a 62% increase in eating disorder visits between 2018–2019 and 2020 (p < .01). No pre pandemic/postpandemic changes were found in the proportion of visits resulting in hospitalization for any of the four diagnostic categories.

Conclusions

Our study suggests significant impacts of COVID-19 on adolescent mental health and a need for further longitudinal research work in this area.

Keywords: Adolescent, COVID-19, Emergency department, Hospitalization, Eating Disorder, Mental Health, Suicidality

Implications and Contribution.

This longitudinal study of pre/post-COVID-19 adolescent mental health–related emergency department visits identified a significant increase in the proportion of mental health visits as well as an increase in visits related to eating disorders in the second half of 2020, highlighting the important burden of COVID-19 on adolescent mental health.

Several studies have reported increases in rates of mental health symptoms [1,2] and increased demand for mental health services since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic [3]. Emergency departments (EDs) are increasingly a first point of contact for youth with acute or emerging mental health problems [4], especially among youth with self-harm and substance use-related concerns [5]. While an increasing number of cross-sectional studies have highlighted the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health measures on youth mental health [6,7], few studies have described changes in ED visits and hospitalization rates for mental health presentations.

Two studies, one of 16 EDs in British Columbia, Canada [8], and the other of a single center in the United States [9], reported significant decreases in mental health–related ED visits (41% and 60% decrease, respectively) during the first two months of the pandemic compared with the same period one year prior. Similarly, a retrospective study from 10 European countries found a significant decrease in the number of psychiatric emergency visits between March and April 2020 versus 2019 with a smaller proportion of youths admitted to an observation unit [10]. However, a small number of studies analyzing ED visits across the United States during the year 2020 showed a significant increase in the proportion of mental health–related visits among all adolescent visits in the second half of 2020 [11,12], with some studies reporting increases in the proportion of some (i.e., eating disorders, suicidality) but not all types of mental health visits [13,14]. In this report, we compare the frequency of mental health–related ED visits and hospitalization rates in adolescents before and after onset of COVID-19.

Methods

This study included all completed pediatric ED visits for adolescents of ages 12–17 years at two high-volume tertiary pediatric Hospitals in Montreal, Canada, between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2020. Patients leaving hospital before receiving care were excluded from the study because no diagnosis code was available. Mental health visits were identified and aggregated into one of four diagnostic categories based on primary discharge diagnosis: eating disorders, suicidal ideation, substance use, or other mental health conditions (including mood, anxiety, psychotic, psychosomatic, and conduct disorders). Diagnoses were available for all patients using electronic health records as free text for one site and as International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10) diagnostic codes at the second site. Categories were agreed upon by consensus between coauthors. A complete list of diagnoses per category for each site is included in Table S1.

Descriptive analyses were conducted to determine the monthly number of mental health visits, in total and per diagnostic category, for the years 2018, 2019, and 2020. Values for 2018 and 2019 were combined and averaged. The proportion of mental health visits out of all adolescent ED visits, and the proportion of visits resulting in hospitalization per diagnostic category were also calculated. Visit counts and proportions were compared between the years 2018–2019 (mean) and 2020 for each calendar month using unpaired t-tests (frequencies) and Z-tests (proportions). A two-sided p value < .05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. All analyses were conducted using Python, version 3.8.3. The study received research ethics board approval from both Sainte-Justine and McGill University Hospitals.

Results

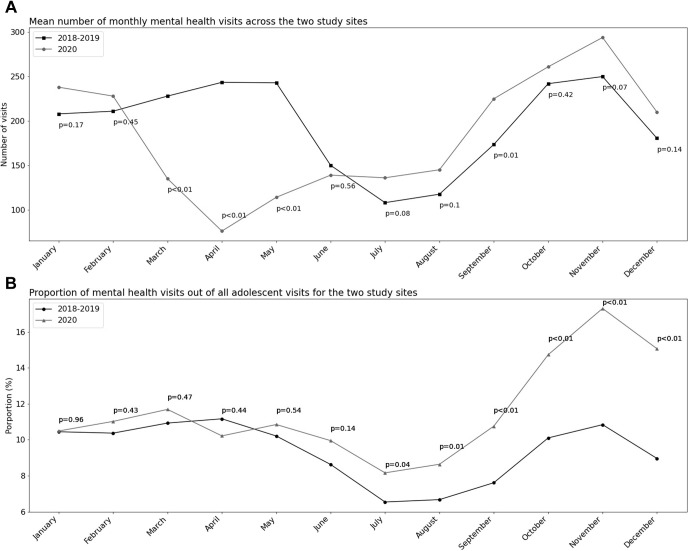

From 2018 to 2020, there was a total of 68,637 visits (mean for 2018–2019: 24,824.5; 2020: 18,988) from adolescents in the two sites including 6,911 (10.1%) mental health–related visits (mean for 2018–2019: 2,355; 2020: 2,201). Figure 1 presents the mean number of monthly ED visits and the proportion of mental health visits among all adolescent ED visits. In comparison to 2018–2019, the number of mental health visits was significantly lower in March, April, and May 2020 (40.8%–68.8% decrease, p < .01) and higher in September (29.7% increase, p = .01). Between July and December 2020, the proportion of mental health visits exceeded 2018–2019, peaking at 17.3% in November (p < .01).

Figure 1.

Mean monthly number of adolescent mental health-related emergency department visits and proportion of mental health–related visits out of all adolescent emergency department visits: 2018–2020. (A) Mean number of monthly mental health visits across the two study sites. (B) Proportion of mental health visits out of all adolescent visits for the two study sites. p values shown for unpaired t-tests (counts) and Z-tests (proportions) comparing number of visits and proportions of mental health visits out of all adolescent visits between 2020 and the mean for 2018 and 2019.

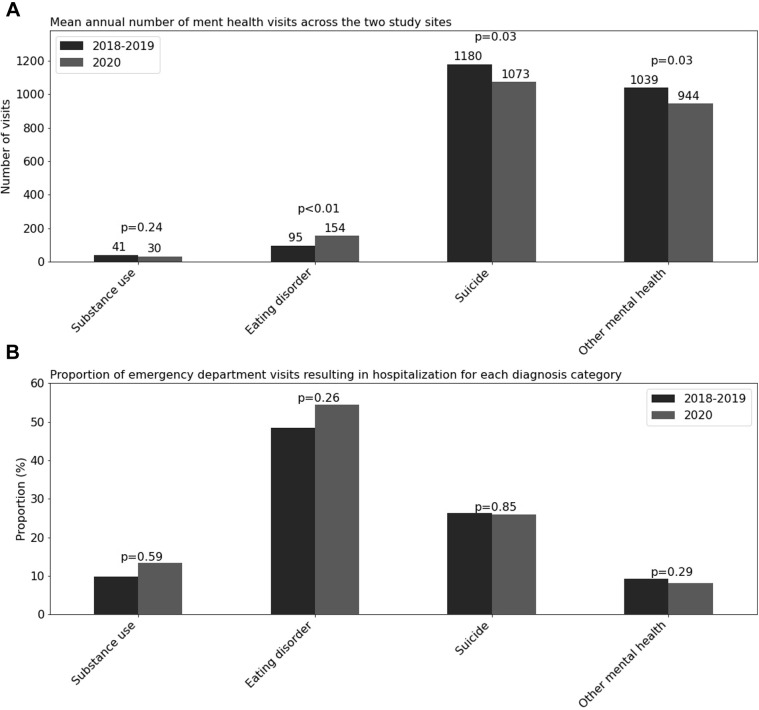

The total number of annual visits increased by 62% for eating disorders in 2020 compared with the mean for 2018–2019 (p < .01), remained stable for substance use, and significantly decreased for suicidal ideation (-9.9%, p = .03) and other mental health conditions (-9.1%, p = .03), as shown in Figure 2 A. The proportion of patients requiring hospitalization within a given diagnostic category did not vary significantly between study periods (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Mean annual number of adolescent mental health-related emergency department visits and proportion of mental health-related visits resulting in hospitalization by diagnosis subtype: 2018-2020. (A) Mean annual number of mental health visits across the two study sites. (B) Proportion of emergency department visits resulting in hospitalization for each diagnosis category. p values shown for unpaired t-tests (counts) and Z-tests (proportions) comparing number of visits and proportions of visits resulting in hospitalization between 2020 and the mean for 2018 and 2019.

Discussion

Consistent with existing literature, our study showed an initial decrease in the number of mental health–related ED visits at the onset of the pandemic followed by a significant increase in the proportion of mental health–related ED visits out of all adolescent ED visits starting in July 2020 [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. The frequency of ED visits related to eating disorders increased markedly during the year 2020, though we did not see such an increase in other mental health diagnoses, such as substance use and other mental health conditions (which included depression and anxiety), a finding that has also been reported in the United States [13,14]. As for hospitalization rates within diagnostic categories, no significant change was noted.

Although we did not see an increase in the overall number of mental health–related ED visits, the observed increase in the proportion of mental health–related ED visits aligns with reported increases in prevalence of mood, anxiety, and eating disorder symptoms in the general population [[15], [16], [17], [18]]. Youth have been less affected by medical complications of COVID-19 [19], and have been less likely to present to the ED for other reasons since the beginning of the pandemic [13]. This could be owing to youth having fewer opportunities to contract other infections and injuries and could explain the increase in proportion of mental health–related visits without an overall increase in visit numbers. Nonetheless, the increase in visits for eating disorders revealed in our study suggests increased need for supportive services for adolescents with these conditions as the pandemic continues to unfold [20].

Our results should be interpreted considering certain limitation. First, our data are restricted to ED visits, and as such, may not be generalizable to the general population outside of the metropolitan area from which the data were collected and do not fully capture the incidence of mental health problems among youth who did not present to a tertiary pediatric ED. Second, there could have been missed mental health cases among the small proportion (2.1%) of adolescent ED visits categorized as “other.” Finally, our study could not account for the potentially reduced access to other services such as school-based and community services, which may have impacted the number of adolescents presenting to the ED.

In conclusion, we found significant increases in the proportion of mental health ED visits among adolescents during the second half of 2020, a period that saw an easing and retightening of COVID-19 preventive measures in Canada. Our study highlights the importance of longitudinally assessing both acute- and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth mental health.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by a Clinical Research Scholar Award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé [Junior 1, OD].

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.036.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Newlove-Delgado T., McManus S., Sadler K. Child mental health in England before and during the COVID-19 lockdown. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:353–354. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh S., Roy D., Sinha K. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113429. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bojdani E., Rajagopalan A., Chen A. COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on psychiatric care in the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113069. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saunders N.R., Gill P.J., Holder L. Use of the emergency department as a first point of contact for mental health care by immigrant youth in Canada: A population-based study. CMAJ. 2018;190:E1183–E1191. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.180277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo C.B., Bridge J.A., Bridge J.A. Children’s mental health emergency department visits: 2007-2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145 doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers A.A., Ha T., Ockey S. Adolescents’ Perceived Socio-Emotional impact of COVID-19 and Implications for mental health: Results from a U.S.-Based Mixed-Methods study. J Adolesc Heal. 2021;68:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magson N.R., Freeman J.Y.A., Rapee R.M. Risk and protective Factors for Prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50:44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldman R.D., Grafstein E., Barclay N. Paediatric patients seen in 18 emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Med J. 2020;37:773–777. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-210273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leff R.A., Setzer E., Cicero M.X., Auerbach M. Changes in pediatric emergency department visits for mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;26:33–38. doi: 10.1177/1359104520972453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ougrin D., Wong B.H.-C., Vaezinejad M. Pandemic-related emergency psychiatric presentations for self-harm of children and adolescents in 10 countries (PREP-kids): A retrospective international cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01741-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leeb R.T., Bitsko R.H., Radhakrishnan L. Mental health–related emergency department visits among children aged <18 Years during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 1–October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1675–1680. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krass P., Dalton E., Doupnik S.K., Esposito J. US pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e218533. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLaroche A.M., Rodean J., Aronson P.L. Pediatric emergency department visits at US Children’s hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2021;147 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-039628. e2020039628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adjemian J., Hartnett K.P., Kite-Powell A. Update: COVID-19 pandemic–associated changes in emergency department visits — United States, December 2020–January 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:552–556. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7015a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bignardi G., Dalmaijer E.S., Anwyl-Irvine A.L. Longitudinal increases in childhood depression symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown. Arch Dis Child. 2020;106:791–797. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barendse M., Flannery J., Cavanagh C. Longitudinal change in adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international collaborative of 12 samples. PsyArXiv Prepr. 2021 doi: 10.31234/OSF.IO/HN7US. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nutley S.K., Falise A.M., Henderson R. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on disordered eating behavior: Qualitative analysis of social media posts. JMIR Ment Heal. 2021;8:e26011. doi: 10.2196/26011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breaux R., Dvorsky M.R., Marsh N.P. Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: Protective role of emotion regulation abilities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rankin D.A., Talj R., Howard L.M., Halasa N.B. Epidemiologic trends and characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infections among children in the United States. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2021;33:114–121. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno C., Wykes T., Galderisi S. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:813–824. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.