Abstract

Societies are looking for ways to mitigate risk while stimulating economic recovery from COVID-19. Facial coverings (masks) reduce the risk of disease spread but there is limited understanding of public beliefs regarding mask usage in the U.S. where mask wearing is divisive and politicized. We find that 83% (±3%) of U.S. respondents in our nationally representative sample believed masks have a role in U.S. society related to the spread of COVID-19 in June 2020. However, 11–24% of these respondents reported not wearing a mask themselves in some public locations. Beliefs about mask wearing and usage vary by respondent demographics and level of agreement with a variety of societal value statements. Agreement with the statement gun ownership is a right based on the U.S. Constitution was negatively correlated with the belief masks had a role in society related to the spread of COVID-19. Agreement with the statements healthcare is a human right and I always wear my seat belt when driving were positively correlated with the belief masks had a role. Only 47% of respondents agreed that “Wearing a mask will help prevent future lock-downs in my community related to COVID-19.” Public perception of the importance of mask usage revealed public transportation, grocery/food stores, and schools, as the relatively most important public places for mask usage among those seven places studied. Results suggest that public health advisories about riskiness of various situations or locations and public perception of importance of risk mitigation by location may not be well aligned.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mask compliance, Public perceptions

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a health crisis but also an economic crisis. Economic decline is known to yield negative health outcomes as tax revenue and public health funding availability declines on the macro level, while individuals experiencing unemployment face devastation on the micro level (McKee and Stuckler, 2020). The complex nature of global supply chains is expected to magnify losses further (Guan et al., 2020). Direct impacts may be more acutely experienced by those facing longer or more intense local impacts; but it remains to be seen how COVID-19-related personal experiences relate to perceptions of risk and/or adoption of risk mitigating practices.

Masks are effective in preventing illness and in asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19 (Eikenberry et al., 2020). Covering one's face in public is a practice which elicits strong responses in the U.S.(Chuck, 2020; Knowles et al., 2020). Currently the CDC recommends, “everyone wear cloth face coverings when leaving their homes, regardless of whether they have fever or symptoms of COVID-19.” (CDCa, 2020). Asian cultures and societies have long embraced mask usage in public, driven at least in part by experiences with SARS (Wong, 2020). Personal costs to mask wearing may include discomfort, expense of obtaining/maintaining masks, and potential lack of communication efficiency involving facial expression (Mehta et al., 2020). The CDC states that mask wearing protects those around the wearer, more so than the wearer (CDCb, 2020). Benefits of wearing a mask in 2020 in response to the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. are fundamentally accrued at the societal level; the impact of one's behavior on others, in the context of mask wearing, is similar to other negative externalities.

A U.S. nationally representative sample of 1198 completed responses was obtained via an online survey conducted on June 12th – 20th, 2020. It was hypothesized that personal COVID-19 experiences and knowledge, societal values held, self-reported engagement in risky personal behaviors outside of COVID-19, and demographics may be related to beliefs about the role of masks. A best-worst scaling (BWS) discrete choice experiment was used to elicit the perceived relative importance of mask wearing among seven public locations among respondents who felt masks had a role to play. Policy makers could use this information to provide information to clarify misconceptions or encourage (or possibly mandate) mask wearing.

2. Methods

Data collection took place June 12, 2020 to June 20, 2020. Kantar, a company which hosts a large opt-in panel database (Kantar, 2020), was used to distribute the survey link to prospective respondents, who were required to be 18 years of age or older. (The survey in its entirety is available as Supplementary Material.) The research process was approved by Oklahoma State University IRB (number: 20–283). Quotas set within Qualtrics, an online survey tool (Qualtrics, 2020), were used to target the proportion of respondents to match the U.S. population for sex, age, education, income, and region of residence (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016). The test of proportions was used to identify statistical differences between the proportions of respondents in each demographic category in the sample obtained versus the U.S. census, and between question subsamples (Acock, 2018; StataCorp, 2019).

In order to analyze the potential impact the number or severity of cases of COVID-19 had on respondent's self-reported beliefs, states were grouped by three different criteria. (1) number of cases over 40,001, which the CDC defined as the worst category at the time (2) the top 10 states defined by COVID-19 cases per capita, and (3) the top 6 states that experienced a rapid increase in COVID-19 cases after Memorial Day 2020. According to the CDC (CDCe, 2020), as of June 17th 2020, 17 states had over 40,001 cases of COVID-19: California, Texas, Louisiana, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan and Illinois. Many of the states with the highest number of COVID-19 cases also have relatively higher populations. Therefore, the number of COVID-19 cases as of June 17, 2020, were divided by the estimated 2019 population according to the U.S. census (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016). The top 10 states with the highest number of COVID-19 cases per capita were New Jersey, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, District of Colombia, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, and Louisiana. In response to reopening plans and post-memorial weekend, six states had record numbers of new cases including Florida, Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Nevada (CBS News, 2020).

All respondents were asked do you agree that masks (meaning any face covering that covers your nose and mouth) have any role in U.S. society related to the spread of viral disease, especially COVID-19, in the June–December 2020 time frame and could select from the answer choices: NO - they have absolutely no role whatsoever in U.S. society or YES - they have some potential role in U.S. society. Information regarding the value of masks, and whether masks protected the wearer or those around them, was still being evaluated in June 2020. For this reason, the questioning began broad, simply asking people if there was ANY role before being presented a series of seven statements regarding mask usage in response to COVID-19 to respond to. Respondents who indicated masks have at least some role were presented a list of 10 locations: in person religious service, big box grocery store/supermarket, specialty grocery store, gym, home improvement store, restaurant, workplace, school, and clothing store/ retail store other than grocery, clothing or home improvement. The respondent was asked to indicate (multiple selections were allowed) if they did not go to this place, if that type of business was not open in their community, if they wore a mask voluntarily, if they were required to wear a mask, and/or if they did not wear a mask.

A series of societal value and personal circumstance statements were curated to gain a better understanding of the underlying beliefs of those who choose to wear or not wear. Respondents were asked to indicate on a scale from 1(strongly agree) to 5(strongly disagree) their level of agreement with nine statements. To establish potential relationships between these statements and the belief masks have a role in U.S. society, Spearman correlations (Spearman, 1904) were calculated (StataCorp, 2019).

To analyze further the relationship between the belief masks have some potential role in U.S. society, demographics, and agreement with statements regarding masks a logit model was employed. Logit model was chosen because the probability of selecting yes masks have a role takes on the value of either 1, or 0. The latent utility (V i) of selecting yes masks play a role is represented by the equation (Train, 2009):

| (1) |

where x i is the vector of observed variables for respondent i and e n is the unobserved error term. Assuming the error term is independently, identically distributed extreme value the logit probability for respondent i becomes (Train, 2009):

| (2) |

The coefficients of latent class models are not directly interpretable so marginal effects, which report the average partial effects between two covariate levels, are reported.

2.1. Best-worst scaling (BWS) discrete choice experiment for prioritizing locations

Respondents who indicated they believed masks had a role in society (n = 996) participated in a BWS choice experiment designed to elicit the relative ranking of importance of public locations to wear a mask among seven locations, including grocery/food stores, home improvement/hardware store, retail settings other than grocery store/home improvement store (i.e. department and other retailers), religious services (i.e. attending church or religious services or gatherings), schools, restaurants, and public transportation (in buses, airplanes, trains or other transportation interacting with any member of the public). The BWS design was determined using the SAS macro SAS %MktBSize (SAS, 2020). Prior to participating in the BWS experiment, respondents were shown the following information: Thinking about societal impacts and welfare broadly speaking in June–December 2020 which locations do you feel mask usage is most important? You will choose the locations with the most important and least important roles in terms of mask usage contributing to human well-being in light of what is currently known about COVID-19. A subset of the locations below will be presented 7 times. Each respondent saw seven choice scenarios (questions), each presenting three of the seven locations for respondents to select among. The respondents' choices of the most important and least important locations for mask usage were used to determine each location's relative position along a continuum from most important to least important. The position of location j on the scale of most important to least important is represented by λ j. Thus, how important a respondent views a particular attribute, which is unobservable to researchers, for respondent i is:

| (3) |

where ℇ ij is a random error term. The probability the respondent i chooses the attribute j as the most important attribute and attribute k as the least important attribute is the probability that the difference between I ij and I ik is greater than all potential differences available from the choices presented. Assuming the error term is independently and identically distributed type I extreme value, the probability of choosing a given most important-least important combination takes the multinomial logit form (Train, 2009), represented by:

| (4) |

Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is used to estimate the parameter λ j, which represents how important attribute j is relative to the least important attribute. One attribute must be normalized to zero to prevent multicollinearity (Train, 2009). A random parameters logit (RPL) model was specified to allow for continuous heterogeneity among individuals as opposed to the multinomial logit model which assumed homogenous preferences. The coefficients are not directly intuitive to interpret, so shares of preferences are calculated (Train, 2009):

| (5) |

and necessarily sum to one across the 7 locations. The calculated preference share for each attribute is the forecasted probability that each attribute is chosen as the most important (Wolf and Tonsor, 2013). We employed the bootstrapping method outlined by Krinsky and Robb (Krinsky and Robb, 1986) to generate the empirical distribution for each location's preference share (confidence interval). The complete combinatorial method (Poe et al., 2005) was employed to evaluate if the preference shares between each location were statistically different.

3. Results

The sample demographics closely matched those of the U.S. population with few exceptions (Table 1 ). Sixty-eight percent of respondents were from states with the highest COVID-19 cases, 15% from those with the highest per capita COVID-19 cases and 22% from states with record new COVID-19 cases as of Memorial Day 2020.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and comparison to U.S. Census N = 1198.

| Demographic variable | Percentage (%) of respondents n = 1198 | P-value of test between sample and census | U.S. Census |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 47 | 0.2977 | 49 |

| Female | 53 | 0.2977 | 51 |

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | 10 | 0.0064 | 13 |

| 25–34 | 18 | 0.9018 | 18 |

| 35–44 | 16 | 0.7936 | 16 |

| 45–54 | 18 | 0.2700 | 17 |

| 55–65 | 17 | 0.8572 | 17 |

| 65 + | 20 | 0.3244 | 19 |

| Income | |||

| $0–$24,999 | 24 | 0.0652 | 22 |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 25 | 0.1231 | 23 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 18 | 0.2381 | 17 |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 13 | 0.1754 | 12 |

| $100,000 and higher | 19 | 0.0000 | 26 |

| Education | |||

| Did not graduate from high school | 3 | 0.0000 | 13 |

| Graduated from high school, did not attend college | 29 | 0.5385 | 28 |

| Attended college, no degree earned | 24 | 0.0178 | 21 |

| Attended college, associates or Bachelor's degree earned | 31 | 0.0006 | 27 |

| Attended college, graduate or professional degree earned | 13 | 0.1488 | 12 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 18 | 0.8005 | 18 |

| South | 39 | 0.4475 | 38 |

| Midwest | 22 | 0.5040 | 21 |

| West | 21 | 0.0111 | 24 |

| COVID-19 cases | |||

| States with highest cases | 68 | ||

| States with highest per capita | 15 | ||

| States with record new cases | 22 |

A statistically higher percentage of respondents (83%) indicated masks had at a potential role than the proportion who said masks had no role (17%) (Table 2 ). For all statements regarding mask wearing in response to COVID-19, the percentage who indicated they believed masks had a role was statistically different from those who did not agree. A higher percentage of respondents with lower incomes (21%) and from a high spike in cases state (21%) did not believe masks had a role when compared to higher income (13%) and not from a high spike in cases state (16%), respectively.

Table 2.

Beliefs regarding mask wearing regarding COVID-19, percentage (%) of respondents for that category. N given in column.

| Believes that masks have a role in U.S. society |

Sex |

Household Income1 |

State COVID-19 status |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample |

Yes |

No |

Male |

Female |

Higher income |

Lower income |

High total |

Not high total |

High per capita |

Not high per capita |

High spike in cases |

Not high spike in cases |

|

| N= | 1198 | 569 | 629 | 610 | 588 | 810 | 388 | 178 | 1020 | 269 | 929 | ||

| NO - masks have absolutely no role whatsoever in U.S. society related to the spread of viral disease | 17Ϯ | 0 | 100 | 18Ϯ | 16Ϯ | 13Ϯ, ψ | 21Ϯ, ψ | 16Ϯ | 19Ϯ | 13Ϯ | 17Ϯ | 21Ϯ, ψ | 16Ϯ, ψ |

| YES - masks have some potential role in U.S. society related to the spread of viral disease | 83Ϯ | 100 | 0 | 82Ϯ | 84Ϯ | 87Ϯ, ψ | 79Ϯ, ψ | 84Ϯ | 81Ϯ | 87Ϯ | 83Ϯ | 79Ϯ, ψ | 84Ϯ, ψ |

| Wearing a mask helps prevent the spread of COVID-19 | 70 Ϯ | 80 Ϯ, ψ | 21 Ϯ, ψ | 68 Ϯ | 72 Ϯ | 71 Ϯ | 69 Ϯ | 72 Ϯ, ψ | 66 Ϯ, ψ | 76Ϯ | 69Ϯ | 67Ϯ | 71Ϯ |

| Wearing a mask helps prevent me from getting COVID-19 | 53Ϯ | 61Ϯ, ψ | 16Ϯ, ψ | 50ψ | 56Ϯ, ψ | 54Ϯ | 52 | 55 Ϯ | 50 | 57 Ϯ | 53 Ϯ | 54 | 53 Ϯ |

| Wearing a mask helps prevent me from spreading COVID-19 | 64 Ϯ | 74Ϯ, ψ | 15Ϯ, ψ | 60 Ϯ, ψ | 68 Ϯ, ψ | 69Ϯ, ψ | 59Ϯ, ψ | 66Ϯ, ψ | 60Ϯ, ψ | 70Ϯ | 63Ϯ | 59 Ϯ | 66 Ϯ |

| Wearing a mask will help prevent future lock-downs in my community related to COVID-19 | 47 Ϯ | 55Ϯ, ψ | 10Ϯ, ψ | 47 Ϯ | 48 | 51ψ | 43 Ϯ, ψ | 51Ϯ, ψ | 41Ϯ, ψ | 52 | 47Ϯ | 43Ϯ | 49 |

| There is social pressure in my community to wear a mask | 31 Ϯ | 29Ϯ, ψ | 42Ϯ, ψ | 35 Ϯ, ψ | 27 Ϯ, ψ | 34Ϯ, ψ | 28Ϯ, ψ | 32Ϯ | 28Ϯ | 33 Ϯ | 30 Ϯ | 30 Ϯ | 31 Ϯ |

| Wearing a mask does not prevent the spread of COVID-19 | 14 Ϯ | 8Ϯ, ψ | 44Ϯ, ψ | 14 Ϯ | 14 Ϯ | 14 Ϯ | 14 Ϯ | 12 Ϯ, ψ | 17 Ϯ, ψ | 10Ϯ | 15Ϯ | 17Ϯ | 13Ϯ |

| Wearing a mask has negative health consequences for the mask wearer | 13Ϯ | 7Ϯ, ψ | 38Ϯ, ψ | 12Ϯ | 13Ϯ | 12Ϯ | 13Ϯ | 11Ϯ, ψ | 16Ϯ, ψ | 11Ϯ | 13Ϯ | 12Ϯ | 13Ϯ |

lower income is defined as less than $49,999 and high income is $50,000 and greater.

indicates the percentage of respondents is statistically different between those who selected they agreed with the statement and those who did not at the <0.05 level. Those who did not select that they agreed with the statement and those who did sum to 100% within a category (i.e. men) and were not included for brevity with the exception of the role of masks in society.

indicates the percentage of respondents between the two levels within a category, for example men vs women, or high total vs not high total are statistically different at the <0.05 level.

For the statement wearing a mask helps prevent the spread of COVID-19 1 a higher percentage of respondents who believed masks had a place in society (80%), and from high case number states (72%) agreed with the statement compared to those who did not believe masks had a place (21%), and non-high case number states (66%), respectively. A higher percentage of those who believed masks had a place in society (61%), and of women (56%) agreed with the statement wearing a mask helps prevent me from getting COVID-19 when compared to those who did not believe masks had a place (16%) and men (50%). A higher percentage of respondents who believed masks had a place in society (74%) compared to those who did not (15%) agreed with the statement wearing a mask helps prevent me from spreading COVID-19.

For the statement wearing a mask will help prevent future lock-downs in my community related to COVID-19 a higher percentage of those who believed masks had a role (55%) compared to those who did not believe (10%), higher income (51%) when compared to lower income (43%) and residents from high total number of COVID-19 case states (51%) when compared to non-high total number of COVID-19 case states (41%) agreed. A higher percentage of people who believed masks did not have a place in society (42%), men (35%) and higher income respondents (34%) agreed with the statement there is social pressure in my community to wear a mask. This is in comparison to those who believed masks had a place (29%), women (27%) and lower income respondents (28%), respectively.

Between 2% and 28% of respondents who indicated they believed masks had a role in society (n = 996) also indicated religious services, gyms, home improvement stores, and schools were not open in their community (Table 3 ). Of those who could have and did attend the listed locations and believed masks had a role in society, between 42% and 63% of respondents voluntarily wore a mask. Only 42% of respondent who went to work indicated they wore a mask in the workplace. Surprisingly, 23% and 24% of respondents who believed masks had a role in society and who could have and did go to the gym, and restaurants (respectively) did not wear a mask.

Table 3.

Locations that respondents who indicated masks have at least some role in society wear a mask. Multiple selections permitted, percentage (%) of respondents.

| Percentage of respondents n = 996 |

Percentage who can and do attend this location (location-specific n provided) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I do not go to this place | This type of business is not open in my community | n | I wear a mask voluntarily | I am required to wear a mask | I do not wear a mask | |

| In person religious service | 49 | 20 | 325 | 54 | 41 | 18 |

| Big box grocery store/supermarket | 9 | 2 | 884 | 64 | 36 | 12 |

| Specialty grocery store | 30 | 5 | 655 | 60 | 41 | 11 |

| Gym | 55 | 23 | 236 | 52 | 40 | 23 |

| Home improvement store | 22 | 4 | 729 | 17 | 13 | 7 |

| Restaurant | 32 | 16 | 525 | 52 | 34 | 24 |

| Workplace | 43 | 11 | 463 | 43 | 53 | 19 |

| School | 54 | 28 | 199 | 59 | 40 | 14 |

| Clothing store | 29 | 13 | 578 | 60 | 33 | 16 |

| Retail store other than grocery, clothing, or home improvement | 18 | 7 | 754 | 63 | 34 | 14 |

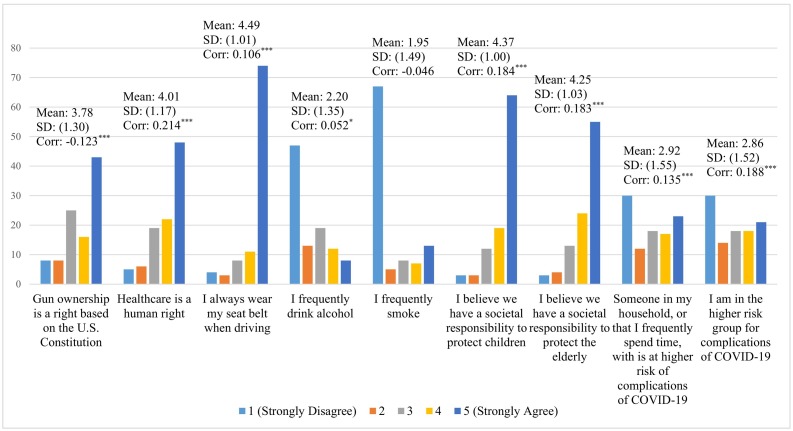

Respondents indicated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) their level of agreement with eight social statements (Fig. 1 ). Agreement with the statement gun ownership is a right based on the U.S. Constitution was negatively correlated with the belief masks had a role in society related to the spread of COVID-19. Agreement with the statements healthcare is a human right and I always wear my seat belt when driving were positively correlated with the belief masks had a role. Belief that we have a societal responsibility to protect children and the elderly were positively correlated with the belief masks had a role in society, as was being at higher risk or having someone in the household or that they spend time with at a higher risk.

Fig. 1.

Agreement with social statements and correlation with belief that masks have a place in society (N = 1198; percentage (%) of respondents). Mean (Standard Deviation) provided in box above bars. Corr indicates the correlation between level of agreement and belief that masks have a place in society. *indicates statistically significant at the 0.10 level **at the 0.05 level *** at the <0.0001 level.

In the logit model estimating the probability a respondent believed masks had a role in society, sex or agreement to the statement there is social pressure in my community to wear a mask was not statistically significantly associated (Table 4 ). As income increased, the probability the respondent believed masks had a place in society increased. Agreeing with the statements wearing a mask helps prevent the spread of COVID-19, wearing a mask helps prevent me from getting COVID-19, wearing a mask helps prevent me from spreading COVID-19, and wearing a mask will help prevent future lock-downs in my community related to COVID-19 increased the probability that the respondent believed masks had a role in society. Agreement with the statements wearing a mask does not prevent the spread of COVID-19 and wearing a mask has negative health consequences for the mask wearer decreased the probability the respondents believed masks had a role in society.

Table 4.

Logit model: dependent variable masks have a role related to the spread of viral disease, independent variables demographics and beliefs regarding masks to mitigate COVID-19 risk. N = 996.

| Marginal effect | Standard error | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | −0.00901 | 0.012359 | 0.4660 |

| Income | 0.017565 | 0.004754 | <0.0000 |

| Wearing a mask helps prevent the spread of COVID-19 | 0.078937 | 0.0154 | <0.0000 |

| Wearing a mask helps prevent me from getting COVID-19 | 0.032513 | 0.014699 | 0.0270 |

| Wearing a mask helps prevent me from spreading COVID-19 | 0.091317 | 0.015667 | <0.0000 |

| Wearing a mask will help prevent future lock-downs in my community related to COVID-19 | 0.068202 | 0.015962 | <0.0000 |

| There is social pressure in my community to wear a mask | −0.00595 | 0.013399 | 0.6570 |

| Wearing a mask does not prevent the spread of COVID-19 | −0.05382 | 0.016986 | 0.0020 |

| Wearing a mask has negative health consequences for the mask wearer | −0.05786 | 0.016734 | 0.0010 |

In the BWS experiment estimation, public transportation had the highest mean preference share (32%), indicating it was the most important location to wear a mask among the seven locations studied (Table 5 ). Grocery/food stores were the second most important (19%) followed by schools (16%). Religious services (13%), retail settings (8%), and home improvement/hardware store (3%) all had statistically smaller preference shares indicating they were less important locations among the seven investigated.

Table 5.

Random parameters logit model results for most important location to wear a mask. N = 996.

| Locations | Coefficient (standard error) | Standard deviation (standard error) | Estimated mean preference share [confidence interval] |

Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grocery/ food stores | −0.537⁎⁎⁎ | 0.695⁎⁎⁎ | 19% [0.178, 0.200] |

2 |

| (0.044) | (0.056) | |||

| Home improvement/ hardware store | −2.314⁎⁎⁎ | 0.952⁎⁎⁎ | 3% [0.029, 0.035] |

6 |

| (0.063) | (0.063) | |||

| Retail settings | −1.387⁎⁎⁎ | 0.514⁎⁎⁎ | 8% [0.076,0.086] |

5 |

| (0.045) | (0.064) | |||

| Religious services | −0.941⁎⁎⁎ | 1.294⁎⁎⁎ | 13% [0.117, 0.138] |

4 |

| (0.056) | (0.059) | |||

| Schools | −0.688⁎⁎⁎ | 1.199⁎⁎⁎ | 16% [0.150, 0.177] |

3 |

| (0.054) | (0.059) | |||

| Restaurants | −1.365⁎⁎⁎ | 0.967⁎⁎⁎ | 8% [0.076, 0.089] |

5 |

| (0.050) | (0.058) | |||

| Public transportation | – | – | 32% [0.310, 0.339] |

1 |

| – | – |

Note: *indicates statistically significant at the 0.10 level **at the 0.05 level *** at the <0.0001 level.

4. Discussion

Recent findings on masks indicate they are more effective than originally thought (Prather et al., 2020) for reducing COVID-19 transmission. Shorter but stricter restrictions on movement, social distancing enforcement, and use of personal protective measures such as hand washing and facemasks are highly successful in containing epidemic spread (López and Rodó, 2020). Seventy percent of respondents believed mask wearing prevented spread, but only 64% correctly identified that masks prevent spread to others. Fifty-three percent of respondents self-reported their belief that masks helped prevent oneself from catching COVID-19. It is important to note that the general knowledge and beliefs regarding the efficacy of masks is continuously evolving. Eighty-three percent of respondents indicated that masks have a role, but even among that group, masks are not worn by 23% in gyms, 24% in restaurants, and 19% in the workplace. Arguably, masks may not be necessary in all workplaces, but most indoor situations would be expected to involve hallways or use of communal spaces necessitating at least some mask usage.

Hypothetical scenarios have suggested near universal (80%) adoption of even moderately effective masks (50%) could prevent 17–45% of projected deaths and decrease peak daily death rate by 34–58% over two months in New York (Eikenberry et al., 2020). Given the amount of economic, financial, social, and societal stress instigated by forced lock-downs in the U.S. thus far, it could be hypothesized that even fear of lockdowns may impact behavior. When asked about how masks play a role in keeping their communities/societies functional, 47% believed wearing a mask would help prevent future lock-downs. Whether the respondent's state was experiencing more or less cases had little relationship to mask wearing.

Optimism bias, in which one has the belief negative consequences are less likely for themselves than others, can be a challenge when considering behaviors that impact COVID-19 risk and spread. Optimism bias helps people avoid experiencing difficult negative emotions, which may aid people in coping while simultaneously leading people to underestimate their probability of catching a disease (Bavel et al., 2020). Already by May 2020, mask usage in grocery stores was reportedly declining (Splitter, 2020). The CDC updated guidance on June 15, 2020 to aid people in deciding whether to go out by assessing relative riskiness of activities (CDCc, 2020).

While people's physical health depends on pandemic control measures and mental and economic health depends on successful reopening of world economies, COVID-19 and mask usage have been politicized. Former President Trump first refused to wear a mask (Liptak, 2020) but then weeks later, which was already months into the pandemic timeline, he donned a mask for the first time (Lemire, 2020) sending media into a frenzy about the delay to public appearance in a mask, whether he would continue the practice, and the potential impact on the behavior of his supporters (BBC News, 2020; Reston, 2020). The politicization of pandemics is not new in U.S. society, having been recognized as a significant factor in the final death rates and counts in the 1918 Spanish Flu (Barry, 2005). Many COVID-19 myths appear to be politically motivated (Fleming, 2020) irreparably linking conversations about public health and societal economic survival with political agendas.

Results from the BWS experiment conducted found mask usage relatively most important for the top three locations of public transportation, grocery/food stores, and schools. Relative importance of masks may be influenced by individual's own circumstances, including the ability to avoid entirely public places perceived as riskiest. Public views on where masks are most valuable may not align with what public health entities advise.

5. Conclusions and implications

Agreement on the statement/belief masks have a role in U.S. society was not equivalent to consistent mask usage as assessed in June 2020. Regardless of the eventual impact of political leaders appearing with or without masks, the interest in such behavior politically, rather than simply as a matter of medical necessity highlights the divisive politicization of the practice. Respondents who did not believe masks had a role in society also often perceived social pressure in their communities to wear a mask. Results are based on data collected in June 2020; given the rapid changes in knowledge about the value of masks in lessening risk of spread of COVD-19 in various circumstances, it is possible that opinions have changed over time. Furthermore, only seven public places were directly ranked in terms of relative importance for mask wearing in the experiment conducted. Additional work with places tailored to individual's circumstances and places visited might yield more conclusive findings about why people perceive or believe that they do about pandemic control measures. Yet, understanding the knowledge of residents and their willingness to comply with masking and other public health measures, even at a single point in time, can extend the ability of public health officials to communicate meaningfully with residents, including those who may have societal viewpoints or higher tolerance for risky behaviors themselves.

Data availability

Data available upon reasonable request.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. These authors contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

In total a small number (43 respondents = 3.5%) selected seemingly contradictory statements, by agreeing with “wearing a mask helps prevent the spread of COVID-19” and “wearing a mask does not prevent the spread of COVID-19”. Possible explanations for these selections are due to fatigue, mistakes, confusion, and/or the inclusion of the word help in one of the statements creating ambiguity in whether masks prevent spread.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106784.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Acock A.C. 6th ed. Stata Press; 2018. A Gentle Introduction to Stata. [Google Scholar]

- Barry J.M. Penguin; 2005. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavel J.J.V., Baicker K., Boggio P.S., Capraro V., Cichocka A., Cikara M., Crockett M.J., Crum A.J., Douglas K.M., Druckman J.M., Drury J., Dube O., Ellemers N., Finkel E.J., Fowler J.H., Gelfand M., Han S., Haslam A.S., Jetten J., Kitayama S., Mobbs D.…Willer R. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020;4:460–471. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BBC News . BBC News; 2020, July 12. Coronavirus: Donald Trump Wears Face Mask for the First Time.https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-53378439 [Google Scholar]

- CBS News . CBS News; 2020, June 17. 6 States Report Record-High Jumps in Coronavirus Cases as Reopening Plans Weighed.https://www.cbsnews.com/news/coronavirus-cases-6-states-report-record-highs/ [Google Scholar]

- CDCa . CDC; 2020. Important Information about your Cloth Face Coverings.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/cloth-face-covering.pdf Retrieved June 22, 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- CDCb . CDC; 2020, June 28. About Cloth Face Coverings.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/about-face-coverings.html Retrieved June 30, 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- CDCc . CDC; 2020, June 15. Deciding to Go out.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/deciding-to-go-out.html Retrieved June 30, 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- CDCe COVID-19 Cases. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html Retrieved June 18, 2020, from.

- Chuck E. NBC News; 2020 Jun 17. Necessary or Needless? Three Months into the Pandemic, Americans are Divided on Wearing Masks.https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/necessary-or-needless-three-months-pandemic-americans-are-divided-wearing-n1231191 [Google Scholar]

- Eikenberry E., Mancuso M., Iboi E., Phan T., Eikenberrry K., Kuang Y., Kostelich E., Gumel A.B. To mask or not to mask: Modeling the potential for face mask use by the general public to curtail the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect. Dis. Model. 2020;5:293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming N. Nature Career Feature. 2020, June 17. Coronavirus misinformation, and how scientists can help to fight it.https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01834-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan D., Wang D., Hallegatte S., Davis S.J., Li S., Bai Y., Lei T., Xue Q., Coffman D., Cheng D., Chen P., Liang X., Xu B., Lu X., Wang S., Hubacek K., Gong P. Global supply-chain effects of COVID-19 control measures. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020;4:577–587. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0896-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantar . Kantar; 2020. About Kantar.https://www.kantar.com/about [Google Scholar]

- Knowles H., Shaban H., Mettler K., Farzan A.N., Armus T., Hassan J., Iati M., Bellware K., Fritz A. The Washington Post; 2020, June 18. Californians Required to Cover their Faces in ‘Most Settings Outside the Home.’.https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/06/18/coronavirus-live-updates-us/ [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky I., Robb A.L. On approximating the statistical properties of elasticities. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1986;68:715–719. doi: 10.2307/1924536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemire J. AP News; 2020, July 11. Trump Wears Mask in Public for First Time during Pandemic.https://apnews.com/7651589ac439646e5cf873d021f1f4b6 [Google Scholar]

- Liptak K. CNN; 2020, May 21. Trump Says He won’t Wear a Mask in Front of the Cameras.https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/21/politics/donald-trump-michigan-masks/index.html [Google Scholar]

- López L., Rodó X. The end of social confinement and COVID-19 re-emergence risk. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M., Stuckler D. If the world fails to protect the economy, COVID-19 will damage health not just now but also in the future. Nat. Med. 2020;26:640–642. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta U.M., Venkatasubramanian G., Chandra P. The “mind” behind the “mask”: assessing mental stats and creating therapeutic alliance amidst COVID-19. Schizophr. Res. 2020;222:503–504. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poe G.L., Giraud K.L., Loomis J.B. Computational methods for measuring the difference of empirical distributions. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2005;87:353–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8276.2005.00727.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prather K.A., Wang C.C., Schooley R.T. Reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;368:1422–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics . Qualtrics; 2020. Online Survey Tool.https://www.qualtrics.com/core-xm/survey-software/ [Google Scholar]

- Reston M. CNN Politics; 2020, July 12. Trump Gives in to the Mask but Takes New Risks with Schools.https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/12/politics/trump-mask-coronavirus-schools-reopening/index.html [Google Scholar]

- SAS The %MktBSize Macro. 2020. https://support.sas.com/rnd/app/macros/MktBSize/mktbsize.htm

- Spearman C.E. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904;15:72–101. doi: 10.2307/1412159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splitter J. Forbes; 2020, May 31. New Grocery Survey finds Fewer Shoppers Taking Safety Precautions to Prevent Coronavirus.https://www.forbes.com/sites/jennysplitter/2020/05/31/new-grocery-survey-finds-fewer-shoppers-taking-safety-precautions-to-prevent-coronavirus/#418f601a112c [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC; College Station: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Train K.E. Cambridge university press; 2009. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . 2016. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Selected Age Groups by Sex for the United States, States, Counties and Puerto Rico Commonwealth and Municipios: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf C.A., Tonsor G.T. Dairy farmer policy preferences. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2013;38(2):220–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wong T. BBC News; 2020 May 12. Coronavirus: Why Some Countries Wear Face masks and other don’t.https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52015486 [cited 2020 Jun 20]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request.