Abstract

Objective

To examine the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on post-acute care utilization and spending.

Design

We used a large national multipayer claims data set from January 2019 through October 2020 to examine trends in posthospital discharge location and spending.

Setting and participants

We identified and included 975,179 hospital discharges who were aged ≥65 years.

Methods

We summarized postdischarge utilization and spending in each month of the study: (1) the percentage of patients discharged from the hospital to home for self-care and to the 3 common post-acute care locations: home with home health, skilled nursing facility (SNF), and inpatient rehabilitation; (2) the rate of discharge to each location per 100,000 insured members in our cohort; (3) the total amount spent per month in each post-acute care location; and (4) the percentage of spending in each post-acute care location out of the total spending across the 3 post-acute care settings.

Results

The percentage of patients discharged from the hospital to home or to inpatient rehabilitation did not meaningfully change during the pandemic whereas the percentage discharged to SNF declined from 19% of discharges in 2019 to 14% by October 2020. Total monthly spending declined in each of the 3 post-acute care locations, with the largest relative decline in SNFs of 55%, from an average of $42 million per month in 2019 to $19 million in October 2020. Declines in total monthly spending were smaller in home health (a 41% decline) and inpatient rehabilitation (a 32% decline). As a percentage of all post-acute care spending, spending on SNFs declined from 39% to 31%, whereas the percentage of post-acute care spending on home health and inpatient rehabilitation both increased.

Conclusions and Implications

Changes in posthospital discharge location of care represent a significant shift in post-acute care utilization, which persisted 9 months into the pandemic. These shifts could have profound implications on the future of post-acute care.

Keywords: Post-acute care, COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic had profound effects on health care delivery, utilization, and spending. Beginning in March 2020, hospital admissions declined as hospitals deferred elective admissions and procedures. Physicians pivoted from in-person care to telemedicine. And many patients deferred health care services. These changes were associated with large and unparalleled declines in medical spending.1

Although changes in hospitalization rates and shifts to telemedicine have been well described, less attention has been paid to how COVID-19 affected post-acute care, which is very commonly used after hospital discharge in the United States and results in high health care spending.2

The effects of COVID-19 on use and spending on post-acute care may be particularly important for nursing homes, one of the most common sites of post-acute care, as they have been particularly hard hit during the pandemic with substantial declines in census3 and revenue, leading to financial instability and closures.4 With higher reimbursement for Medicare-paid skilled nursing stays, post-acute care admissions are an important source of revenue for nursing homes and has been a large and often growing part of Medicare's budget for years. In 2018, one-fifth of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries were discharged to a skilled nursing facility (SNF), costing Medicare $28.5 billion.2

Understanding how the pandemic has altered use of post-acute care is critically important to informing expectations and policies aimed at funding post-acute care and optimizing the use of post-acute care moving forward, particularly for nursing homes.

In this article, we use a large national data set to document COVID-19–associated changes in the utilization and spending on post-acute care.

Data and Methods

We used multipayer deidentified noncapitated claims data from FAIR Health. FAIR Health is an independent nonprofit organization that maintains a data repository that contains privately billed medical and dental claims contributed by more than 60 payors nationwide. We used longitudinal data including more than 70 million commercially insured individuals, including Medicare Advantage beneficiaries.

We identified all hospital discharges for patients aged ≥65 years between January 2019 and October 2020. Using their first location of care after hospital discharge, we identified each discharge's subsequent postdischarge destination—including the 3 most common sites of post-acute care [home with home health care, admission to a skilled nursing facility (SNF), or inpatient rehabilitation facility] and discharge home for self-care. We excluded the approximately 2% of hospital discharges that went to long-term acute care hospitals, hospice, or other institutional settings such as psychiatric hospitals.

We calculated postdischarge utilization and spending in each month of the study using 4 measures: (1) the percentage patients discharged from the hospital and admitted to each of the 4 postdischarge locations and (2) the rate of discharge to each postdischarge location per 100,000 insured members in our cohort (to account for the decline in hospitalizations during the COVID-19 pandemic). We also calculated the monthly spending on post-acute care over this time period as (3) total amount spent in each post-acute care location and (4) the percentage of spending in each post-acute care location out of the total spending across the 3 post-acute care settings.

The study was reviewed by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and determined not to be human subjects research.

Results

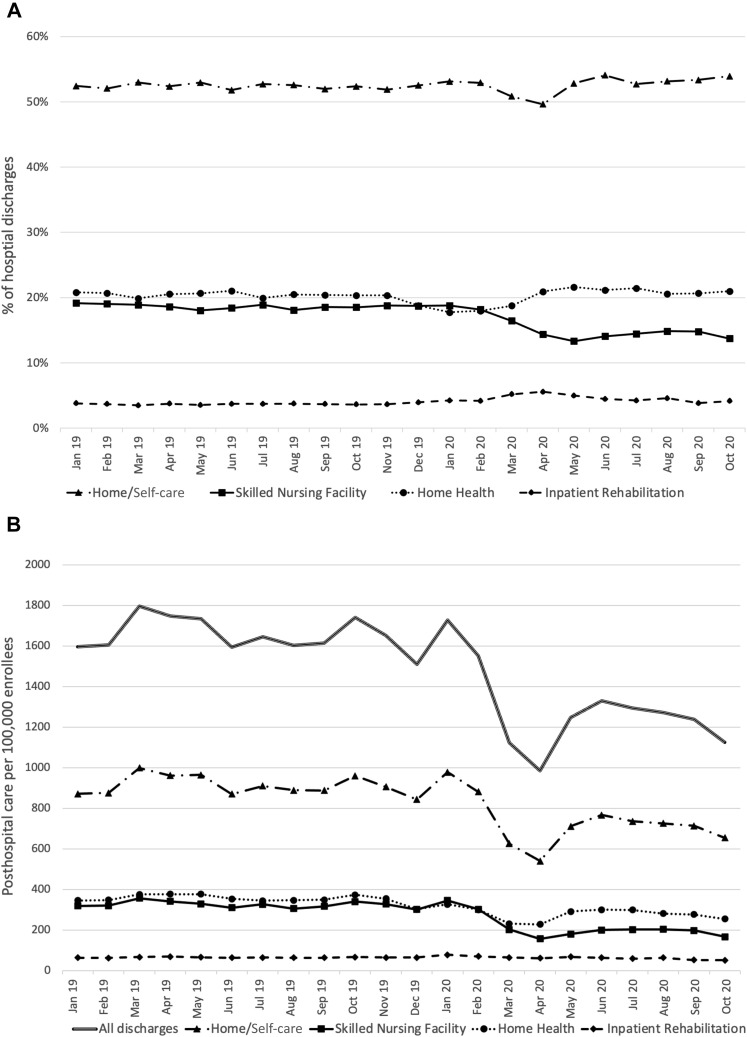

We identified and included 975,179 hospital discharges who were 65 years or older. The percentage of discharges to each of the 4 postdischarge locations remained steady in 2019. In 2020, the percentage of patients discharged home for self-care or with home health increased slightly (from an average of 52% in 2019 to 54% in October 2020 for self-care; 20%-21% for home health; Figure 1 A). The percentage of patients discharged to inpatient rehabilitation did not meaningfully change. The use of SNF declined over this time period, from an average of 19% of discharges in 2019 to 14% in October 2020.

Fig. 1.

Trends in destination after hospital discharge to the 4 most common discharge destinations (home with self-care, skilled nursing facility, home with home health, and inpatient rehabilitation). (A) Percentage of all hospital discharges. (B) Rate per 100,000 insured members.

The rate of post-acute care use per 100,000 enrollees declined in March and April 2020 in most settings owing to the decline in hospitalizations in those months (Figure 1B). Although these rates rebounded by October 2020 to 72% (in home health) and 78% (in inpatient rehabilitation) of the prepandemic rate, the rate of SNF use did not rebound in the same way but, rather, remained low. SNF use declined from 324 SNF admissions per 100,000 enrollees on average in 2019 to 167 SNF admissions per enrollee in October 2020, a level that was 51% of the prepandemic rate.

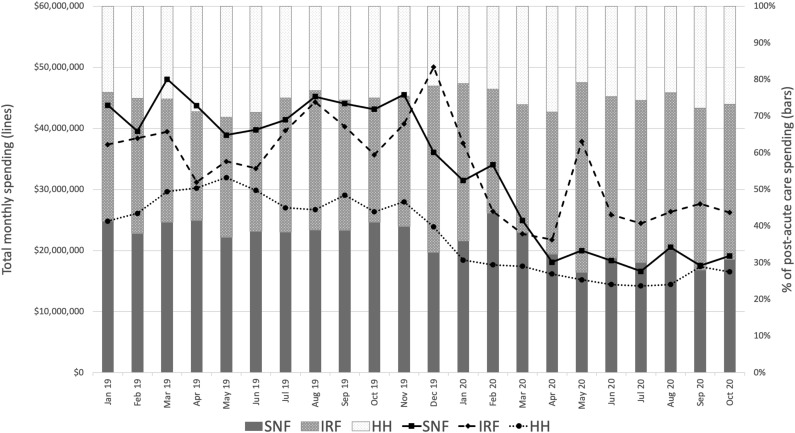

The total amount spent declined in each of the 3 post-acute care locations. SNF spending declined the most, from an average of $42 million per month in 2019 to $19 million in October 2020, a 55% decline (trend lines in Figure 2 ). The relative declines in total spending in home health and inpatient rehabilitation were smaller by comparison. Home health spending declined from an average of $28 million per month in 2019 to $16.5 million in October 2020, a 41% decline; inpatient rehabilitation spending declined from an average of $39 million per month in 2019 to $26 million in October 2020, a 32% decline.

Fig. 2.

Trends in spending on the 3 most common settings for formal post-acute care. The trend lines display the total monthly spending in each setting. The stacked bars display the monthly spending in each of these 3 settings as a percentage of total spending across these 3 post-acute care settings. HH, home with home health; IRF, inpatient rehabilitation; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

When examining spending in each post-acute care location as a percentage of all post-acute care spending, we found that spending shifted away from SNFs and toward home health and inpatient rehabilitation. As a percentage of post-acute care spending, spending on SNFs declined from 39% to 31% (stacked bars in Figure 2). On the other hand, the percentage of post-acute care spending on home health and inpatient rehabilitation both increased. Spending on home health increased slightly from an average of 26% in 2019 to 27% in October 2020; spending on inpatient rehabilitation increased from 36% to 42%.

Discussion

In a large, national, commercially insured cohort, post-acute care utilization declined during the pandemic. The largest and most persistent declines in utilization were in SNFs, where spending also substantially declined to less than half of what it was in 2019. A larger portion of posthospital-discharge care was delivered at home, though total spending on home health also declined.

Trends away from institutional post-acute care existed before the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicare and other payers implemented a number of alternative payment arrangements over the last decade, such as accountable care organizations and bundled payments that hold providers accountable for total costs of care. With its high costs and high rates of utilization,2 reducing skilled nursing facility utilization has been a common target in these alternative payment models to reduce health care spending. As a result, home-based care was becoming more common after hospital discharge, even before the pandemic.5 With the pandemic, we document an acceleration in these trends, particularly in SNFs, likely due to concerns about COVID-19 rates in nursing homes.

These changes in post-acute care utilization have important implications for patients, families, and caregivers. First, shifting postdischarge care home is often consistent with patient preferences. However, it may also shift the burden of care to family members or other unpaid caregivers.6 Although home health care is often available after hospital discharge, its benefits may not provide sufficient care to patients recovering from hospitalization, who often need short-term help with activities of daily living. Families and friends often must fill in these gaps in care.

Second, shifting care home may result in worse outcomes for some patients. There is increasing concern that beyond limitations in the level of help for activities of daily living, current models of home-based care may also provide insufficient medical care to care for ill patients recovering from hospitalization.7 Prior research has found that compared with patients who receive post-acute care in nursing homes, those we are discharged home have higher rehospitalization rates.8 , 9 Further development of more intensive support for home-based post-acute care models may be needed for some conditions,10 particularly those higher acuity conditions that may benefit the most from more intensive posthospital follow-up. In the meantime, it is important to monitor the impact of lower rates of institutional post-acute care on patient outcomes.

Third, the trend in declining use of SNF for post-acute care may hasten the decline of nursing homes,11 which were experiencing falling admissions and revenue prior to the pandemic. There are well-described financial benefits to nursing homes of providing post-acute care. Post-acute stays in nursing homes are typically paid for by Medicare, at generous per-diem rates that result in high financial margins for nursing homes.2 Long stays, on the other hand, are commonly paid for by Medicaid, at lower daily rates that may not cover the costs of delivering care. Although post-acute care is a relatively small proportion of overall nursing home care, it is a financially important source of revenue for nursing homes. This is particularly relevant in the post-COVID era, as the pandemic has harmed the finances of many nursing homes owing to a declining census12 and the increased costs needed to adequately respond to the pandemic in terms of equipment, supplies, and staffing. The general consensus is that nursing homes use Medicare-based revenue to cross-subsidize Medicaid stays.2 , 13 With the decline in post-acute care in nursing homes and the accompanying decline in payment to nursing homes that we document, nursing homes may be losing an important source of revenue. The decline in SNF admissions may hasten a change in the role of nursing homes,11 , 14 causing nursing home to focus more on long-term care as post-acute care admissions decline. This specialization in long-term care may benefit patients, but given the lower Medicaid reimbursement rates, may also cause nursing homes to become more financially unstable and, in the worst case, forcing some to close.

It is unknown whether these trends will continue as the pandemic fades and what the full implications of these shifts on patients, families, and health care systems are. However, they suggest there may be a fundamental shift in providing post-acute care at home, rather than in nursing homes. If we are to continue to support the growth of care at home, we will need to expand the availability of and access to paid personal care assistance, which is currently an optional benefit in Medicaid and therefore subject to considerable state variation. We may also need to consider more widespread implementation of more intensive home-based post-acute care models that can more feasibly substitute for SNF care.15 These trends may also hasten a reckoning with the instability of the nation's nursing homes and their current inadequate financing.

Footnotes

Rachel Werner is supported by K24-AG047908 from the National Institute on Aging.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McWilliams J.M., Russo A., Mehrotra A. Implications of early health care spending reductions for expected spending as the COVID-19 pandemic evolves. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:118–120. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MedPAC . Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; Washington, DC: 2020. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werner R.M., Coe N.B. Nursing home staffing levels did not change significantly during COVID-19: Study examines US nursing home staffing levels during COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood) 2021;40:795–801. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spanko A. Skilled Nursing News; 2021. Nursing home industry projects $34B in revenue losses, 1,800 closures or mergers due to COVID.https://skillednursingnews.com/2021/02/nursing-home-industry-projects-34b-in-revenue-losses-1800-closures-or-mergers-due-to-covid/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett M.L., Wilcock A., McWilliams J.M., et al. Two-year evaluation of mandatory bundled payments for joint replacement. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:252–262. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1809010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatterjee P., Hoffman A.K., Werner R.M. Shifting the burden? Consequences of postacute care payment reform on informal caregivers. Health Affairs Blog. 2019 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190828.894278/full/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett M.L., Mehrotra A., Grabowski D.C. Postacute care—the piggy bank for savings in alternative payment models? N Engl J Med. 2019;381:302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1901896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner R.M., Coe N.B., Qi M., Konetzka R.T. Patient outcomes after hospital discharge to home with home heath care versus to skilled nursing facility. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:617–623. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose L. The effects of skilled nursing facility care: Regression discontinuity evidence from Medicare. Am J Health Econ. 2020;6:39–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werner R.M., Van Houtven C.H. In the time of COVID-19, we should move high-intensity postacute care home. Health Affairs Blog. 2020 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200422.924995/full/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller M. New York Times; New York: 2021. Turning away from nursing homes, to what? [Google Scholar]

- 12.Begley T.A., Weagley D. Firm finances and the spread of COVID-19: Evidence from nursing homes. Georgia Tech Scheller College of Business Research Paper No. 3659480. 2021. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3659480 Available at:

- 13.Troyer J.L. Cross-subsidization in nursing homes: Explaining rate differentials among payer types. South Econ J. 2002;68:750–773. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werner R.M., Hoffman A.K., Coe N.B. Long-term care policy after Covid-19—Solving the nursing home crisis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:903–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2014811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Augustine M.R., Davenport C., Ornstein K.A., et al. Implementation of post-acute rehabilitation at home: A skilled nursing facility-substitutive model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1584–1593. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]