Abstract

Sixty-seven clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae (40 of serotype 23F, 19 of serotype 19F, and 8 of serotype 6B) with decreased susceptibilities to penicillin and erythromycin were characterized by antimicrobial susceptibility patterns; DNA restriction endonuclease cleavage profiles of the penicillin-binding protein genes pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x; random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) patterns generated by arbitrarily primed PCR; and chromosomal macrorestriction profiles based on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. A total of 22 clones (identical or closely related pulsotypes and identical RAPD patterns) were identified; 14 clones of 23F, 6 of 19F, and 2 of 6B. Three 23F clones (26 isolates) and one 19F clone (9 isolates) expressed high-level resistance to penicillin, cefotaxime, and erythromycin (MICs ≥ 256 μg/ml). These data strongly suggest that multiple high-level penicillin-, extended-spectrum cephalosporin-, and macrolide-resistant clones of S. pneumoniae have been disseminated in Taiwan.

The emergence of strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae resistant to penicillin, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, and macrolides has become a considerable concern in many parts of the world, including Taiwan, as it limits the options available for the treatment of serious pneumococcal infections (1, 8, 10, 11, 14, 17, 25). Previous observations provide strong evidence that the spread of penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae in a geographic area may be due to transfer of mosaic pbp genes from resistant isolates into susceptible isolates (horizontal spread) or to dissemination of a pneumococcal clone (clonal spread) (2, 3, 6, 7, 13, 26). In addition, dissemination of a multidrug-resistant S. pneumoniae (MDRSP) phenotype to additional serotypes due to in vivo capsular transformation may occur (3, 13, 16). Dissemination of serotype 23F MDRSP or other serotype clones of S. pneumoniae has been documented in several countries; however, no reported clones possessed extremely high resistance to erythromycin (MICs ≥ 256 μg/ml) (5, 12, 18, 20–22, 24, 27).

Bacterial isolates.

A total of 67 isolates (40 of serotype 23F, 19 of serotype 19F, and 8 of serotype 6B) of S. pneumoniae with reduced susceptibilities to penicillin and erythromycin recovered from various clinical specimens from patients who were treated at National Taiwan University Hospital, a tertiary referring center with 2,000 beds in northern Taiwan, from January 1996 to December 1997 were studied. These isolates were recovered from 67 patients, 30 adults and 37 children, who resided in the northern part of Taiwan. Sources of the isolates included sputum or bronchial secretion (34 isolates), blood (14 isolates), ear-nose-throat-sinus (10 isolates), wound and pus (6 isolates), cerebrospinal fluid (2 isolates), and bile (1 isolate). All isolates were identified by conventional methods (25).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs of seven antimicrobial agents for the 67 isolates, determined by the agar dilution method with Mueller-Hinton agar containing 5% sheep blood (BBL Microbiology Systems), were adopted from our previous study (10). MIC breakpoints for defining susceptibility and resistance were in accordance with the 1998 guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, except for gentamicin and cefpirome, for which no criteria were provided (23). MDRSP was defined as showing intermediate or high-level resistance to penicillin and resistance to one or more classes of the other antibiotics tested. Antibiotypes of the isolates were considered to be different if the MIC of at least one of the antimicrobial agents tested was a ≥2-dilution discrepancy.

DNA fingerprinting of genes encoding pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x.

Segments of the pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x genes of the isolates were amplified from chromosomal DNA by PCR with the previously described oligonucleotide primers (21). Gene fingerprinting of the segments of the pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x genes was performed with the restriction enzymes HinfI and AluI (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) (18, 26).

RAPD analysis.

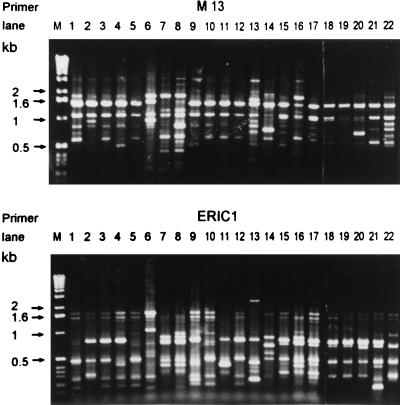

The preparation of isolates for random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis, generated by arbitrarily primed PCR, and extraction of genomic DNA were as described previously (9). Three primers were used: M13 (5′-GAGGGTGGCGGTTCT-3′), ERIC1 (5′-GTGAATCCCCAGGAGCTTACAT-3′), and OPA-7 (5′-GAAACGGGTG-3′). Patterns differing by more than one band were considered to be different.

PFGE analysis.

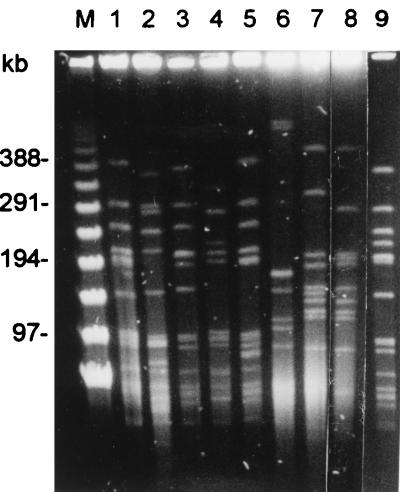

DNA fingerprinting of the isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis was performed in accordance with previous descriptions (15, 19). The DNA was digested by SmaI, and the fragments were resolved by PFGE in 1% agarose (SeaKem GTC agarose; FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer for 20 h at 14°C and 6 V/cm with a CHEF-DRIII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.). Interpretation of PFGE profiles (pulsotypes) was in accordance with the criteria described by Tenover et al. (28).

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the isolates are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Among the isolates, 22 different clones were identified, including 22 RAPD patterns (patterns A to V) and 22 different pulsotypes (profiles a to v) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Figure 2 shows the pulsotypes of the nine clones (clones 1 to 9) of serotype 23F with high-level resistance to penicillin. Isolates having the same pulsotypes and RAPD patterns all belonged to different serotypes. Among the 22 clones, 17 antibiotypes were identified (Table 2) and all isolates were MDRSP. Forty-four (66%) isolates belonging to 11 clones had erythromycin MICs of ≥256 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 67 penicillin- and erythromycin-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates

| Clone (no. of isolates) | Antibiotype | Serotype | RAPD patterna | Pulsotype | Fingerprint profile

|

Source(s) (no. of isolates)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pbp1a | pbp2x | pbp2b | ||||||

| 1 (16) | A | 23F | A | a | I | I | I | Blood (4), CSF (1), S/B (8), throat (3) |

| 2 (4) | B | 23F | B | b | II | II | II | Blood (2), S/B (1), sinus (1) |

| 3 (3) | C | 23F | C | c | III | II | III | Blood (1), S/B (2) |

| 4 (1) | B | 23F | D | d | IV | II | IV | S/B (1) |

| 5 (1) | D | 23F | E | e | III | II | IV | Nose (1) |

| 6 (1) | E | 23F | F | f | V | II | III | Throat (1) |

| 7 (1) | F | 23F | G | g | VI | II | V | S/B (1) |

| 8 (1) | A | 23F | H | h | IV | II | V | S/B (1) |

| 9 (6) | B | 23F | I | i | III | II | IV | Blood (1), S/B (4), nose (1) |

| 10 (2) | G | 23F | J | j | VII | II | III | Blood (1), S/B (1) |

| 11 (1) | H | 23F | K | k | III | III | IV | Sinus (1) |

| 12 (1) | I | 23F | L | l | IV | II | III | S/B (1) |

| 13 (1) | B | 23F | M | m | III | IV | III | S/B (1) |

| 14 (1) | J | 23F | N | n | IV | II | III | Pus (1) |

| 15 (4) | K | 19F | O | o | VI | II | IV | Pus (1), S/B (2), ear (1) |

| 16 (1) | A | 19F | P | p | IV | III | III | S/B (1) |

| 17 (2) | L | 19F | Q | q | IV | II | IV | Blood (1), pus (1) |

| 18 (2) | M | 19F | R | r | IV | V | V | Blood (1), S/B (1) |

| 19 (9) | N | 19F | S | s | IV | II | IV | S/B (6), wound (2), blood (1) |

| 20 (1) | O | 19F | T | t | III | II | V | Blood (1) |

| 21 (7) | P | 6B | U | u | III | V | IV | CSF (2), S/B (2), blood (1), Bile (1), wound (1) |

| 22 (1) | Q | 6B | V | v | III | II | V | Ear (1) |

Generated by PCR with primers OPA-7, M13, and ERIC1.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; S/B, sputum or bronchial secretion.

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of 67 isolates of S. pneumoniae and their antibiotypes

| Clone (no. of isolates) | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Antibiotype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | Cefotaxime | Cefpirome | Imipenem | Gentamicin | Ciprofloxacin | Erythromycin | ||

| 1 (16) | 4 | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 32 | 1 | ≥256 | A |

| 2 (4) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 32 | 1 | ≥256 | B |

| 3 (3) | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 1 | ≥256 | C |

| 4 (1) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 32 | 1 | ≥256 | B |

| 5 (1) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 8 | 1 | 4 | D |

| 6 (1) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 32 | 2 | 2 | E |

| 7 (1) | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 32 | 1 | 4 | F |

| 8 (1) | 8 | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 32 | 2 | ≥256 | A |

| 9 (6) | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 16 | 1 | ≥256 | B |

| 10 (2) | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 2 | G |

| 11 (1) | 0.12 | 0.06 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | 16 | 1 | ≥256 | H |

| 12 (1) | 1 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 32 | 1 | 64 | I |

| 13 (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 16 | 0.5 | ≥256 | B |

| 14 (1) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.06 | ≤0.03 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 8 | J |

| 15 (4) | 2 | 0.5 | ≤0.03 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | K |

| 16 (1) | 8 | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 32 | 2 | ≥256 | A |

| 17 (2) | 0.25 | 0.12 | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | L |

| 18 (2) | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 | ≤0.03 | 16 | 0.5 | 16 | M |

| 19 (9) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 1 | ≥256 | N |

| 20 (1) | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 16 | 1 | 1 | O |

| 21 (7) | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.25 | 32 | P |

| 22 (1) | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 1 | 2 | 4 | Q |

FIG. 1.

RAPD patterns generated by arbitrarily primed PCR of the 22 clones of S. pneumoniae with two primers, M13 and ERIC1. Molecular sizes (lane M) are indicated in kilobases (Gibco BRL).

FIG. 2.

PFGE profiles of SmaI-digested chromosomal DNA of nine clones of serotype 23F S. pneumoniae isolates. Lane M is a molecular size standard for a bacteriophage λ ladder (Gibco BRL); lanes 1 to 9 show clones 1 to 9, respectively.

Of the 14 clones (clones 1 to 14) of isolates belonging to serotype 23F, two major clones (clones 1 and 9) comprised 55% (22 isolates) of the isolates; these isolates all had high-level resistance to penicillin and erythromycin, with MICs of ≥256 μg/ml. Clone 1 isolates were also highly resistant to cefotaxime (MICs of 8 μg/ml) and cefpirome (MICs of 4 μg/ml). Among the 31 isolates belonging to the five clones (clones 1, 2, 3, 9, and 10) resulting in dissemination (more than one isolate included in a single clone), the majority were recovered from sputum or bronchial secretion (52%), followed by blood (29%), and 26 isolates (84%) were recovered from children.

Among the 19 isolates of serotype 19F, six distinct clones were identified, with one principal clone (clone 19) comprising nine closely related isolates which had intermediate resistance to penicillin but had erythromycin MICs of ≥256 μg/ml. Clonal dissemination was found in four clones (clones 15 and 17 to 19). Seven (88%) of the serotype 6B isolates belonged to one clone (clone 21), and all had intermediate resistance to penicillin (MICs of 0.5 μg/ml). Among these seven isolates, four were recovered from children.

Among the 67 isolates, seven fingerprint profiles of pbp1a, five of pbp2b, and five of pbp2x were identified (Table 1). All isolates of the same clones had identical pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x fingerprint profiles, confirming their clonal origin. Isolates of clone 1 had unique pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x gene fingerprint profiles, which were different from those obtained from other clones. Twenty-two of the 24 serotype 23F isolates, other than clone 1, had the same pbp2x fingerprint profile (profile II) as the 16 isolates of serotype 19F. The same pbp2b fingerprint profile (profile IV) was obtained from 9 isolates (clones 4, 5, 9, and 11) of serotype 23F and 16 isolates (clones 15, 17, 19, and 20) of serotype 19F. Twenty-seven isolates including nine different clones (clones 4, 5, 8, 9, 15, 17, 19, 20, and 22) had identical pbp2x (profile II) and pbp2b (profile IV) fingerprint profiles. The pbp2x (profile II) and pbp2b (profile III) fingerprint profiles were found in eight serotype 23F isolates of five different clones (clones 3, 6, 10, 12, and 14). Two clones (clones 5 and 9), comprising seven isolates of serotype 23F, had identical pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x fingerprint profiles and identical antibiotypes for β-lactam antibiotics. Identical susceptibilities to β-lactam antibiotics and restriction profiles of pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x were also found in two serotype 6B isolates (clones 20 and 22).

In our previous survey we noted a marked increase in erythromycin resistance in clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae, from 9.1% in 1984 to 85.8% in 1997, in Taiwan (10). In addition, the resistance rate of penicillin increased from 1.6% in 1992 to 66.2% in 1997, of which 60% of the isolates had high-level resistance and the majority belonged to serotypes 23F, 19F, or 6B (10). Our prior study also showed that a surprisingly large fraction of the isolates belonged to serotype 23F (from 8.8% during 1984 to 1986 to 32.5% during 1996 to 1997), and the majority of the isolates had less susceptibility to penicillin and high-level resistance to erythromycin (MICs ≥ 256 μg/ml) (8, 10). This suggests that epidemic spread of a few bacterial clones occurred in this area.

In the present study, three important points regarding the molecular epidemiology of the most frequently encountered serotypes of clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae with reduced susceptibility to penicillin and erythromycin were clarified. First, four major clones (clones 1, 9, 19, and 21) involving serotypes 23F, 19F, and 6B have obviously been disseminated in Taiwan. The majority of these isolates were highly resistant to penicillin, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, and erythromycin (MICs ≥ 256 μg/ml). Second, several isolates expressing serotype 23F or 19F and having identical altered pbp genes and β-lactam susceptibilities had different RAPD patterns and PFGE profiles (different clones), suggesting that the occurrence of horizontal transfer of pbp genes between strains is likely. Third, none of the isolates originating from a common ancestor (a single clone) expressed different serotypes, indicating that serotype (capsular) transformation in vivo did not occur in these strains.

Although resistant pneumococci may be selected due to antibiotic pressure in a given geographic area, it is suggested that the spread of individual highly resistant clones has contributed to the emergence of worldwide resistance (20). In the present study, one of the principal clones (clone 1, serotype 23F) comprises 16 isolates recovered from different patients, showing that this clone has been widely spread in northern Taiwan. A similar scenario might be seen with serotypes 19F (clone 19) and 6B (clone 21) in the near future in Taiwan.

In this study, we did not simultaneously compare the pbp gene fingerprint profiles or PFGE profiles of our serotype 23 clones with the South African or Spanish erythromycin-resistant serotype 23F clone. However, dissemination of the Spanish or South African 23F clone to Taiwan is not likely, for three reasons. First, the origins of serotype 23F isolates in northern Taiwan appeared to be heterogeneous, since 14 distinct clones were clearly identified. Multiplication of a single imported clone is not the only process used to explain the recent upsurge in the proportion of penicillin- and erythromycin-resistant serotype 23F isolates. Second, our principal clone of serotype 23F (clone 1) had an antibiotype, i.e., high MICs (≥256 μg/ml) of erythromycin as well as high penicillin and cefotaxime MICs (4 and 8 μg/ml, respectively), which was different from that of the Spanish or South African clone. Third, we compared the PFGE profiles of our disseminated serotype 23 clones with those of the Spanish clone published in the literature, and no identical or closely related profiles were found (4, 19).

In conclusion, our data strongly suggest that multiple high-level penicillin-, extended-spectrum cephalosporin-, and macrolide-resistant clones of S. pneumoniae have become disseminated in Taiwan. This might explain the extremely high rates of resistance to these drugs in clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae recovered in Taiwan. Clinicians in Taiwan should be alerted to the possible spread of these multiresistant strains, which may pose serious dilemmas for the treatment of patients with infections caused by these organisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by a grant (NSC86-2314-B-002-053) from the National Science Council, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelbaum P C. Antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: an overview. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:77–83. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes D M, Whittier S, Gilligan P H, Soares S, Tomasz A, Henderson F W. Transmission of multidrug-resistant serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae in group day care: evidence suggesting capsular transformation of the resistant strain in vivo. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;171:890–896. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffey T J, Dowson C G, Daniels M, Zhou J, Martin C, Spratt B G, Musser J M. Horizontal transfer of multiple penicillin-binding protein genes, and capsular biosynthetic genes, in natural populations of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2255–2260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey T J, Daniels M, McDougal L K, Dowson C G, Tenover F C, Spratt B G. Genetic analysis of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with high-level resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1306–1313. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffey T J, Berron S, Daniels M, Garcia-Leoni M E, Cercenado E, Bouza E, Fenoll A, Spratt B G. Multiply antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae recovered from Spanish hospital (1988–1994): novel major clones of serotypes 14, 19F and 15. Microbiology. 1996;142:2747–2757. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-10-2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowson C G, Hutchinson A, Brannigan J A, George R C, Hansman D, Linares J, Tomasz A, Smith J M, Spratt B G. Horizontal transfer of penicillin-binding protein genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8842–8846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall L M C, Whiley R A, Duke B, George R C, Efstratiou A. Genetic relatedness within and between serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United Kingdom: analysis of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:853–859. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.853-859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsueh P R, Chen H M, Lu Y C, Wu J J. Antimicrobial resistance and serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated in southern Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 1996;95:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsueh P R, Teng L J, Lee P I, Yang P C, Hung L M, Chang S C, Lee C Y, Luh K T. Outbreak of scarlet fever at a hospital day care centre: analysis of strain relatedness with phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. J Hosp Infect. 1997;36:191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(97)90194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsueh, P. R., L. J. Teng, L. N. Lee, P. C. Yang, S. W. Ho, and K. T. Luh. Extremely high prevalence of macrolide and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Taiwan. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Klugman K P. Pneumococcal resistance to antibiotics. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:171–196. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klugman K P, Coffey T J, Smith A, Wasas A, Meyers M, Spratt B G. Cluster of an erythromycin-resistant variant of the Spanish multiply-resistant 23F clone of Streptococcus pneumoniae in South Africa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:171–174. doi: 10.1007/BF01982193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laible G, Spratt B G, Hakenbeck R. Interspecies recombination events during the evolution of altered PBP 2× genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1993–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H J, Park J Y, Jang S H, Kim J H, Kim E C, Choi K W. High incidence of resistance to multiple antimicrobials in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from a university hospital in Korea. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:826–835. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefevre J C, Faucon G, Sicard A M, Gase A M. DNA fingerprinting of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2724–2728. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2724-2728.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefevre J C, Bertrand M A, Faucon G. Molecular analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae from Toulouse, France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:491–497. doi: 10.1007/BF02113426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marton A, Gulyas M, Munoz R, Tomasz A. Extremely high incidence of antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Hungary. Clin Infect Dis. 1991;163:542–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDougal L K, Facklam R, Reeves M, Hunter S, Swenson J M, Hill B C, Tenover F C. Analysis of multiply antimicrobial-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2176–2184. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDougal L K, Rasheed J K, Biddle J W, Tenover F C. Identification of multiple clones of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2282–2288. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGee L, Klugman K P, Friedland D, Lee H J. Spread of the Spanish multi-resistant serotype 23F clone of Streptococcus pneumoniae to Seoul, Korea. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:253–257. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moissenet D, Valcin M, Marchand V, Garabedian E, Geslin P, Garbarg-Chenon A, Vu-Thien H. Molecular epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae with decreased susceptibility to penicillin in a Paris children’s hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:298–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.298-301.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munoz R, Coffey T J, Daniels M, Dowson C G, Laible G, Casal J, Hakenbeck R, Jacobs M, Musser J M, Spratt B G, Tomasz A. Intercontinental spread of a multiresistant clone of serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:302–306. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standard for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: eighth informational supplement, M100-S8. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reichmann P, Varon E, Gunther E, Reinert R R, Luttiken R, Marton A, Geslin P, Wagner J, Hakenbeck R. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Germany: genetic relationship to clones from other European countries. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:377–385. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-5-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruoff K L. Streptococcus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith A M, Klugman K P, Coffey T J, Spratt B G. Genetic diversity of penicillin-binding protein 2B and 2X genes from Streptococcus pneumoniae in South Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1938–1944. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.9.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soares S, Kristinsson K G, Musser J M, Tomasz A. Evidence for the introduction of a multiresistant clone of serotype 6B Streptococcus pneumoniae from Spain to Iceland in the late 1980s. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:158–163. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P, Murray B, Persing D, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]