Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Non-fermentative Gram-negative Bacilli (NFGNB) is known as a major cause of healthcare-associated infections with high levels of antibiotic resistance. The aim of this study was to investigate the antibiotic resistance profiles and molecular characteristics of metallo-beta-lactamase (MBL)-producing NFGNB.

Materials and Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, the antibiotic resistance profile of 122 clinical NFGNB isolates was determined by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion and microdilution broth methods. Bacterial isolates were investigated for the detection of MBLs production using the combination disk diffusion Test (CDDT). The existence of blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaNDM genes in all carbapenem-resistant isolates was determined employing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays.

Results:

High resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa was reported to cefotaxime and minocycline, whereas Acinetobacter baumannii isolates were highly resistant to all antibiotics except colistin. Multidrug resistance (MDR)-NFGNB (66% vs. 12.5%, P=0.0004) and extensively drug resistant (XDR)-NFGNB (55.7% vs. 12.5%, P=0.001) isolates were significantly more common in hospitalized patients than in outpatients. The production of MBL was seen in 40% of P. aeruginosa and 93.3% of A. baumannii isolates. It was found that 33.3% and 46.7% of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates, and 13.3% and 28.9% of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates were harboring blaIMP-1 and blaVIM-1 genes, respectively. The incidence of MDR (98.2% vs. 28.3%, P<0.001) and XDR (96.4% vs. 11.7%, P<0.001) in MBL-producing NFGNB isolates was significantly higher than non-MBL-producing isolates.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated a higher rate of resistance among NFGNB isolates with an additional burden of MBL production within them, warranting a need for robust microbiological surveillance and accurate detection of MBL producers among the NFGNB.

Keywords: Gram-negative bacteria, Carbapenems, Anti-bacterial agents, Metallo-beta-lactamase, Carbapenem resistance

INTRODUCTION

Non-fermentative Gram-negative bacilli including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia are opportunistic pathogens with a highly variable level of virulence that rarely causes disease in healthy individuals. However, these bacteria as one of the most important nosocomial pathogens can cause severe infections such as bacteremia, urinary tract and surgical site infections in hospitalized and immunocompromised patients (1–3).

The ever-increasing emergence of antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, and S. maltophilia strains has become a health concern worldwide. Currently, the choice of appropriate treatment options for patients with multidrug-resistant NFGNB infections is a serious challenge (4, 5). The increasing incidence of resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillins and cephalosporins among NFGNB represents a significant clinical problem nowadays. Nevertheless, the carbapenems are often considered to be the last resort for the treatment of infections associated with MDR-NFGNB isolates (6, 7).

Carbapenem resistance in NFGNB, especially in P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii, is an emerging global threat to public health and is a cause of concern as many nosocomial NFGNB isolates are resistant to most other antibiotics. Notably, S. maltophilia is intrinsically resistant to many classes of antibiotics such as carbapenems (2, 8). The most common mechanism of carbapenem resistance in NFGNB is the production of carbapenemases, such as Ambler classes A, B, and D enzymes. MBLs belong to Amber class B type of beta-lactamase and exhibit a broad spectrum of activity to all penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems (9, 10). The worldwide emergence and spread of MBLs represent a major threat to human health care not only due to their ability to confer a high level of resistance but also because their genes carried highly mobile elements, which are the main cause of their dissemination in the hospital setting (11, 12). The occurrence rates of five different types of MBLs including IMP, VIM, SPM, GIM, and SIM are increasing rapidly, and among them, IMP and VIM are most predominant. Furthermore, NDM-1 is a novel type of MBLs that has emerged as a serious threat to the treatment of bacterial infections (13, 14).

Given the rising emergence of antibiotic resistance in MBL-producing NFGNB and the fact that clinical infections caused by these bacteria are often associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality (5, 6), this study aimed to investigate the antibiotic resistance profiles and molecular characteristics of MBL-producing NFGNB isolates in Birjand, South-East Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This cross-sectional study was conducted on a total of 122 non-duplicate clinical NFGNB isolates collected from out-patients and in-patients (hospital stay >48 hours at the time of specimen collection) referred to Birjand Imam Reza Hospital, in Iran from Jan 2018 to May 2019. The clinical samples contained urine, wound swab, blood, and lung secretions. The study was approved by the Birjand University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (IR. BUMS.REC.1395.130).

Identification of NFGNB isolates.

All collected samples were inoculated onto 5% Sheep Blood agar (Merck, Germany) and MacConkey Agar (Merck, Germany) and incubated aerobically at 37°C ± 2°C for 24 hours. The clinical NFGNB isolates were characterized and identified by conventional microbiological methods and biochemical testing (Such as colonial morphology, Gram staining, the alkaline reaction on Triple Sugar Iron agar [Merck, Germany], oxidation/fermentation test [Merck, Germany], motility, oxidase test [Rosco, Denmark], and growth at 42°C ± 2°C).

Notably, the 16S rRNA PCR with specific primers was used for molecular confirmation of P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, and S. maltophilia isolates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Target genes and their primers used in this study.

| Primers | Sequence (5′-3′) | Products sizes (bp) | Annealing (ºC) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bla IMP | Fw- GGAATAGAGTGGCTTAAYTCTC | 232 | 52 | (17) |

| Rv- GGTTTAAYAAAACAACCACC | ||||

| bla VIM | Fw- GATGGTGTTTGGTCGCATA | 390 | 59 | (18) |

| Rv- CGAATGCGCAGCACCAG | ||||

| bla NDM | Fw- GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC | 621 | 52 | (17) |

| Rv- CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC | ||||

| 16S rRNA (P. aeruginosa) | Fw- GGGGGATCTTCGGACCTCA | 956 | 58 | (19) |

| Rv- TCCTTAGAGTGCCCACCCG | ||||

| 16S rRNA (A. baumannii) | Fw- TTTAAGCGAGGAGGAGG | 240 | 56 | (20) |

| Rv- ATTCTACCATCCTCTCCC | ||||

| 16S rRNA (S. maltophilia) | Fw- AGTTCGCATCGTTTAGGG | 762 | 58 | (21) |

| Rv- ACGGCAGCACAGAAGAGC |

Antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST).

The antibiotic resistance profile of the isolates was determined according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (15). The Kirby-Bauer disk-diffusion method was used for susceptibility testing to amikacin (30 μg), piperacillin/tazobactam (100/10 μg), imipenem (10 μg), meropenem (10 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), levofloxacin (5 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 μg) (MAST, UK). Furthermore, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by the microdilution broth method for colistin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) according to CLSI guidelines (15). Briefly, 100 μl of twofold serial dilutions of colistin were dispensed into wells of 96-well plates and the bacterial suspension (100 μl) with final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/ml was added to each well of the microtiter plate. Finally, plates were incubated at 37°C ± 2°C for 18–24 hours. E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used for quality control of antibiotic susceptibility testing. It is noteworthy that MDR in NFGNB isolates was defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories and XDR as non-susceptibility to at least one agent in all but two or fewer antimicrobial categories (16).

Phenotypic screening of MBL producing isolates.

Bacterial isolates with resistance to carbapenems and/or resistance to other broad-spectrum beta-lactams such as ceftazidime were investigated for the detection of MBLs production by the combination disk diffusion Test (CDDT) using imipenem disks (10 mg) (MAST, UK) solely and in combination with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). An increase of ≥7 mm in the zone diameter of imipenem tested in combination with EDTA versus imipenem alone was considered as MBLs positive. The S. maltophilia isolates, as inherent carriers of an MBL gene, were excluded (7, 17). P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used as the control.

PCR assays for detection of MBLs genes.

The existence of blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaNDM genes in all carbapenem-resistant isolates was determined employing PCR assays with specific primers described in Table 1. Genomic DNA was extracted from pure cultures of the NFGNB isolates using High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was conducted on the summation of all volumes consisting of 25 μl (12.5 μl of 2× Hot Star Taq Master Mix, 2 μl of the DNA template, 1 μl of each primer (10 pmol/ μl) and 8.5 μl of ddH2O) using the Taq PCR Master Mix Kit (Amplicon, Denmark). DNA amplification was performed in a thermocycler (PEQLAB, Erlangen, Germany) with an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 5 minutes; 35 amplification cycles each for 1 minute at 94°C, 40 seconds at different temperatures for different genes (Table 1), and 50 seconds at 72°C; and followed by an additional extension step of 10 minutes at 72°C. The amplified products were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel containing 1× RedSafe DNA stain (Intron, USA).

Sequencing of amplicons was performed on the purified PCR products by an ABI PRISM 3700 sequencer (Macrogen, Korea). The nucleotide sequences were analyzed using Chromas software (version 1.45) and compared with sequences in the GenBank using the national center for biotechnology information (NCBI) basic local alignment search tool (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Statistical analysis.

The data were entered and analyzed using SPSS statistical software (version 21). Frequency and percentages were calculated, as well as the Pearson chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were done whenever applicable with P-values of less than 0.05 regarded as statistically significant. It is noteworthy that the S. maltophilia isolates, as chromosomal MBL-producers, were excluded from the statistical analysis related to the distribution of MBL producing isolates.

RESULTS

Patients and bacterial isolates.

Out of the total 122 NFGNB isolates isolated from different clinical samples, 66 (54.1%), 50 (41%) and 6 (4.9%) were P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, and S. maltophilia, respectively. The majority of the isolates were originated from lung secretions (56 isolates, 45.9%), followed by wound (42 isolates, 34.4%), urine (18 isolates, 14.8%), and blood (6 isolates, 4.9%).

Among the 122 isolates obtained, 70 (57.4%) were from males and 52 (42.6%) were from females. The mean age of patients was 39.15 ± 17.52 years old (range of 1–73 years), of which 106 (86.9%) were hospitalized and 16 (13.1%) were out-patients.

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns in NFGNB.

The results of the antimicrobial resistance determinations of P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, and S. maltophilia isolates are shown in Table 2. High resistance in P. aeruginosa was reported to cefotaxime and minocycline (84.8% [56 out of 66 isolates] and 59.1% [39 out of 66 isolates], respectively), whereas A. baumannii isolates were highly resistant to all studied antibiotics except colistin. It is noteworthy that 16.7% (one out of 6 isolates) of S. maltophilia isolates exhibited resistance to each of minocycline, levofloxacin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Finally, antimicrobial resistance was observed to be higher in A. baumannii than in P. aeruginosa, and S. maltophilia.

Table 2.

Resistance pattern of non-fermentative Gram-negative bacilli (NFGNB) isolates to different antimicrobial agents according to CLSI guidelines (15).

| Antimicrobial agents | No. of isolates (%) showing antibiotic resistance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| P. aeruginosa (n=66) | A. baumannii (n=50) | S. maltophilia (n=6) | |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 13 (19.7) | 46 (92) | NT |

| Amikacin | 15 (22.7) | 42 (84) | NT |

| Aztreonam | 17 (25.8) | 47 (94) | NT |

| Levofloxacin | 10 (15.2) | 45 (90) | 1 (16.7) |

| Gentamicin | 24 (36.4) | 43 (86) | NT |

| Minocycline | 39 (59.1) | 45 (90) | 1 (16.7) |

| Ceftriaxone | NT | 46 (92) | NT |

| Ceftazidime | 15 (22.7) | 44 (88) | NT |

| Cefotaxime | 56 (84.8) | 45 (90) | NT |

| Cefepime | 19 (28.8) | 44 (88) | NT |

| Imipenem | 8 (12.1) | 44 (88) | NT |

| Meropenem | 12 (18.2) | 45 (90) | NT |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | NT | 45 (90) | 1 (16.7) |

| Colistin | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

NT: antibiotics not tested or not recommended by CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute).

The results revealed that out of 122 NFGNB isolates, 59.8% (72 isolates) were MDR and 50% (61 isolates) of them identified as XDR. The incidence of MDR and XDR in P. aeruginosa isolates was reported at 34.8% (23/66) and 19.7% (13/66), and in A. baumannii isolates at 98% (49/50) and 96% (48/50), respectively. However, only one out of six S. maltophilia isolate (16.7%) was characterized as MDR according to the antibiotics tested in this study. MDR-NFGNB (66% vs. 12.5%, P=0.0004) and XDR-NFGNB (55.7% vs. 12.5%, P=0.001) isolates were significantly more common in hospitalized patients than in outpatients. Moreover, the frequency of these MDR/XDR isolates was reported significantly higher in the burn ward than in other wards (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of MDR/XDR among 122 NFGNB isolates by patient characteristics.

| Item/Status | NFGNB isolates | NFGNB isolates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MDR (%)

(n=72) |

Non-MDR (%)

(n=50) |

P-value |

XDR (%)

(n=61) |

Non-XDR (%)

(n=61) |

P-value | |

| Hospitalization Status | ||||||

| In-patients | 70 (66) | 36 (34) | 0.0004 | 59 (55.7) | 47 (44.3) | 0.001 |

| Out-patients | 2 (12.5) | 14 (87.5) | 2 (12.5) | 14 (87.5) | ||

| Hospital Wards | ||||||

| Surgery | 10 (47.6) | 11 (52.4) | 0.001 | 5 (23.8) | 16 (76.2) | 0.0005 |

| Burn | 29 (72.5) | 11 (27.5) | 28 (70) | 12 (30) | ||

| ICU | 31 (68.9) | 14 (31.1) | 26 (57.8) | 19 (42.2) | ||

| Out-patients | 2 (12.5) | 14 (87.5) | 2 (12.5) | 14 (87.5) | ||

MDR: Multidrug-resistant, XDR: Extensively drug-resistant, NFGNB: Non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli, ICU: Intensive care unit.

Distribution of MBL-producing NFGNB and MBL genes.

In the current study, carbapenems resistance was observed in 15 (22.7%) and 45 (90%) P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii isolates, respectively. Out of 60 carbapenems resistance isolates, 48 (80%) strains were determined as phenotypic MBL producers. The production of MBL was seen in 40% (6/15) of P. aeruginosa and 93.3% (42/45) of A. baumannii isolates.

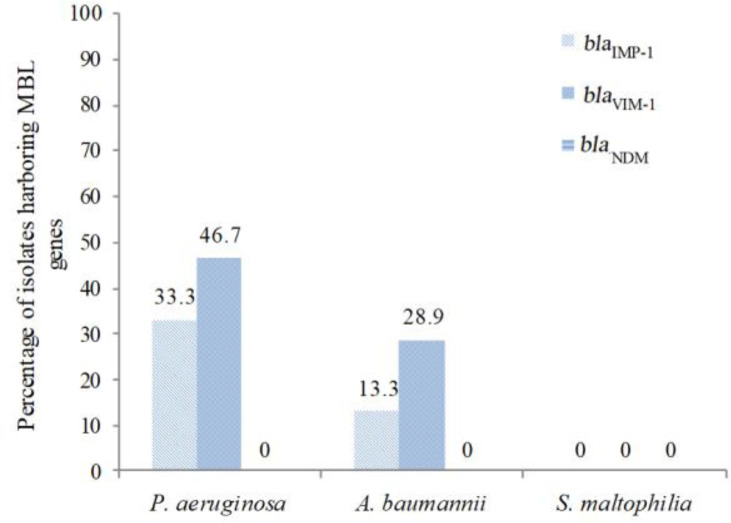

The existence of blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaNDM genes was determined in all carbapenem-resistant NFGNB isolates. It was found that 33.3% (5 out of 15 isolates) and 46.7% (7 out of 15 isolates) of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates, and 13.3% (6 out of 45 isolates) and 28.9% (13 out of 45 isolates) of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates were harboring blaIMP-1 and blaVIM-1 genes, respectively (Fig. 1). However, the blaNDM gene was not detected in any of the isolates. The PCR amplification of MBL genes from NFGNB isolates is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of MBL genes among carbapenem-resistant NFGNB isolates.

MBL: Metallo-beta-lactamase, NFGNB: Non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli.

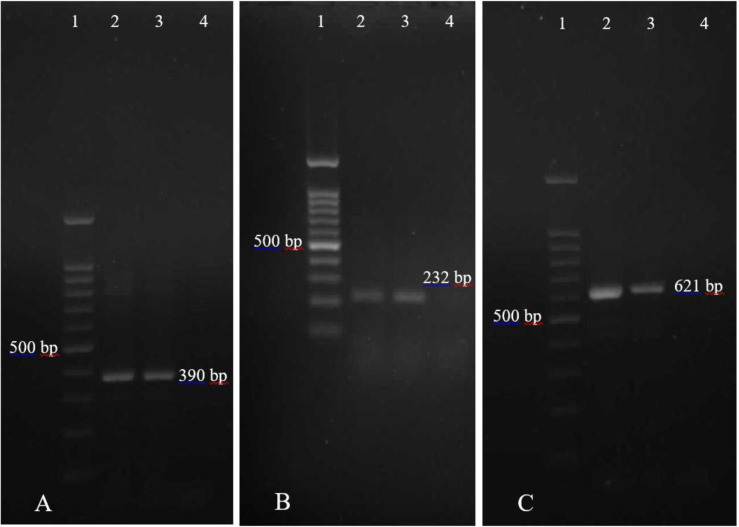

Fig. 2.

PCR amplification products of MBL genes from NFGNB isolates. (A) PCR amplification of blaVIM-1 gene. Lane 1, DNA marker (100 bp); Lane 2 and 3, Clinical isolates positive for blaVIM-1 (390 bp); Lane 4, Negative control. (B) PCR amplification of blaIMP-1 gene. Lane 1, DNA marker (100 bp); Lane 2 and 3, Clinical isolates positive for blaIMP-1 (232 bp); Lane 4, Negative control. (C) PCR amplification of blaNDM gene. Lane 1, DNA marker (100 bp); Lane 2 and 3, Positive control isolates for blaNDM (621 bp); Lane 4, Negative control.

MBL: Metallo-beta-lactamase, NFGNB: Non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli.

Distribution and antibiotic resistance of MBL-producing NFGNB.

Out of total 56 phenotypic and/or genotypic MBL-producing NFGNB isolates, 98.2% (55 isolates) and 96.4% (54 isolates) were characterized as MDR and XDR, respectively. The incidence of MDR (98.2% vs. 28.3%, P<0.001) and XDR (96.4% vs. 11.7%, P<0.001) in MBL-producing NFGNB isolates was significantly higher than non-MBL-producing NFGNB isolates. Furthermore, MBL-producing NFGNB isolates (55% vs. 6.3%, P=0.0002) were significantly more common in hospitalized patients than in outpatients that the isolates had the highest frequency in the burn ward (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution and antibiotic resistance of MBL-producing NFGNB isolates.

| Item/Status | NFGNB isolates* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| MBL (%) (n=56) | Non-MBL (%) (n=60) | P-value | |

| Hospitalization Status | |||

| In-patients | 55 (55) | 45 (45) | 0.0002 |

| Out-patients | 1 (6.3) | 15 (93.8) | |

| Hospital Wards | |||

| Surgery | 5 (26.3) | 14 (73.7) | 0.0001 |

| Burn | 25 (64.1) | 14 (35.9) | |

| ICU | 25 (59.5) | 17 (40.5) | |

| Out-patients | 1 (6.3) | 15 (93.8) | |

| MDR | |||

| Yes | 55 (98.2) | 17 (28.3) | <0.001 |

| No | 1 (1.8) | 43 (71.7) | |

| XDR | |||

| Yes | 54 (96.4) | 7 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| No | 2 (3.6) | 53 (88.3) | |

MBL: Metallo-beta-lactamase, MDR: Multidrug-resistant, XDR: Extensively drug-resistant,

NFGNB: Non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli, ICU: Intensive care unit.

S. maltophilia isolates, as chromosomal MBL-producers, were excluded.

DISCUSSION

Non-fermentative Gram-negative bacilli have emerged as a significant cause of healthcare-associated infections. The ever-increasing emergence of antibiotic resistance in NFGNB and the lack of new antibacterial agents is a major challenge for treating patients suffering from infections caused by them (1, 23).

In the present study, high resistance in P. aeruginosa was reported to cefotaxime and minocycline (84.8% and 59.1%, respectively), whereas A. baumannii isolates were highly resistant to all antibiotics except colistin. It is noteworthy that colistin, imipenem, levofloxacin, and meropenem were found to be the most effective antibiotics against P. aeruginosa. In our study, antimicrobial resistance was observed to be higher in A. baumannii than in P. aeruginosa. The pattern of antibiotic resistance for P. aeruginosa in our study is similar to many previous studies (2, 5, 6, 10). Furthermore, high resistance to most antibiotics in A. baumannii has also been reported in many studies in which colistin was introduced as the most effective antimicrobial agent against the isolates (2, 4, 5, 7). Finally, S. maltophilia isolates in our study exhibited resistance to minocycline, levofloxacin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (each was 16.7%).

Ever-increasing resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in S. maltophilia isolates has been reported interestingly in some studies (22, 24–26), and the emergence of resistance to this antibiotic, as the firstline therapy for S. maltophilia infection, threatens the treatment of infections caused by them. Overall, the increasing emergence of antibiotic resistance in NFGNB isolates is a serious problem in developing countries, especially because of the relatively easy access to over-the-counter antibiotics (2, 21).

The results revealed that the incidence of MDR and XDR in P. aeruginosa isolates was 34.8% and 19.7%, and in A. baumannii isolates 98% and 96%, respectively. However, only one S. maltophilia isolate (16.7%) was characterized as MDR in this study. A similar pattern of results was obtained in many studies, which reported a high frequency of MDR and XDR strains in NFGNBs, especially among A. baumannii isolates (23, 27–29). In contrast to our findings, some studies reported the different prevalence of MDR and XDR strains in NFGNBs (5, 6, 21, 30). This difference could be attributed to factors such as geographical area, type of patients, hospitalization status, and history of antibiotic use. Moreover, MDR-NFGNB (66% vs. 12.5%, P=0.0004) and XDR-NFGNB (55.7% vs. 12.5%, P=0.001) isolates were significantly more common in hospitalized patients than in outpatients. The frequency of these MDR/XDR isolates in our study was reported significantly higher in the burn ward than in other wards. In line with the results of this study, El-Mahallawy and et al., in 2015 also stated that the incidence of MDR-NFGNB isolates was significantly higher among hospitalized patients than outpatients (28). In another study, the level of resistance in Acinetobacter species was significantly higher in the isolates originating from inpatients (31). Farajzadeh Sheikh and colleagues in 2020 showed that the frequency of MDR P. aeruginosa isolates was higher in the burn ward than in other wards (14). It should be noted that the high occurrence of MDR/XDR NFGNB isolates among hospitalized patients, especially patients admitted to the burn ward is not surprising due to the use of various antibiotics for treatment as well as long hospital stays.

The worldwide emergence and spread of MBLs, as one of the most common carbapenem resistance mechanisms, is a major threat to human health care not only due to their ability to confer a high level of resistance but also because their genes carried highly mobile elements (11, 12). In the current study, carbapenems resistance was observed in 15 (22.7%) and 45 (90%) P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii isolates, respectively. Out of 60 carbapenems resistance isolates, 48 strains (80%) were determined as phenotypic MBL producers. The production of MBL was seen in 40% and 93.3% of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii isolates, respectively. Previous studies from India (8, 12), Nepal (5), Romania (27), Egypt (28), and other research from Iran (7, 11, 14) also showed a rising trend in the carbapenem resistance among NFGNB isolates. It seems that the high pressure of antibiotics due to greater empirical or indiscriminate use of antibiotics can lead to carbapenem resistance in the hospital setting. Moreover, consistent with our study, a large outbreak of MBL-producing NFGNB infections, especially due to A. baumannii isolates were described in India (8, 9), Brazil (1), Pakistan (32), and Nepal (33). In the present study, it was found that 33.3% and 46.7% of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates, and 13.3% and 28.9% of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates were harboring blaIMP-1 and blaVIM-1 genes, respectively. However, the blaNDM gene was not detected in any of the isolates. Similar results on the distribution of carbapenem-resistance genes with the predominance of the blaVIM gene were also reported from many studies (6, 7, 11, 34). Finally, the incidence of MDR (98.2% vs. 28.3%, P<0.001) and XDR (96.4% vs. 11.7%, P<0.001) in MBL-producing NFGNB isolates in our study was significantly higher than non-MBL-producing NFGNB isolates. Furthermore, MBL NFGNB isolates (55% vs. 6.3%, P=0.0002) were significantly more common in hospitalized patients than in outpatients that the isolates had the highest frequency in the burn ward. In line with the results of this study, Choudhary and et al., in 2019 also indicated that the prevalence of MDR/ XDR P. aeruginosa isolates was significantly higher among the MBL group as compared to that in the non-MBL group (35). Another study found that MBL positive isolates of A. baumannii were showing significantly higher resistance to all antimicrobials agents as compared to MBL negative isolates (8). In the study of Argenta and colleagues (2017), high levels of antibiotic resistance were reported in MBL-producing NFGNB isolates compared to Non-MBL isolates (1). In a previous study, all MBL-producing P. aeruginosa was isolated from In-patients only (10). Overall, the accurate identification and reporting of MBL-producing NFGNB isolates would help select suitable antimicrobial therapy and prevent the further spread of these MDR isolates. Consequently, it is generally recommended that all carbapenem-resistant NFGNB isolates to be tested for MBL production.

A limitation of this study was the small sample size for S. maltophilia isolates, which could affect the likelihood of detecting antibiotic resistance and metallo-beta-lactamase genes in these isolates. Given this, the investigation of the pattern of antibiotic resistance and the frequency of metallo-beta-lactamase genes in S. maltophilia isolates with appropriate sample size may be of interest for future studies.

CONCLUSION

Our findings showed a high rate of carbapenem- and MDR resistant isolates among the NFGNB, especially A. baumannii isolates. The results indicated that colistin was still an effective antibiotic for the treatment of infections caused by NFGNB. A high prevalence of MDR/XDR phenotypes among the MBL-producing NFGNB isolates highlights the importance of accurate identification of MBL producers and judicious use of carbapenems to prevent the further spread of these bacteria. The presence of these resistant bugs strongly reflects the need to rapidly promote the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship policies and robust microbiological surveillance programs in the hospitals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran (grant number 4263).

REFERENCES

- 1.Argenta AR, Fuentefria DB, Sobottka AM. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated from clinical samples at a tertiary care hospital. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2017; 50: 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta R, Malik A, Rizvi M, Ahmed M. Presence of metallo-beta-lactamases (MBL), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) & AmpC positive non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli among intensive care unit patients with special reference to molecular detection of blaCTX-M & blaAmpC genes. Indian J Med Res 2016; 144: 271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Usha Rani P, Vijayalakshmi P. Detection of metallo-beta-lactamase production in rare carbapenem-resistant non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli isolated in a tertiary care hospital, Visakhapatnam, India. J Med Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 4: 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta V. Metallo beta lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter species. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2008; 17: 131–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yadav SK, Bhujel R, Mishra SK, Sharma S, Sherchand JB. Emergence of multidrug-resistant non-fermentative gram negative bacterial infection in hospitalized patients in a tertiary care center of Nepal. BMC Res Notes 2020; 13: 319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farhan SM, Ibrahim RA, Mahran KM, Hetta HF, Abd El-Baky RM. Antimicrobial resistance pattern and molecular genetic distribution of metallo-β-lactamases producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from hospitals in Minia, Egypt. Infect Drug Resist 2019; 12: 2125–2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarashi S, Goudarzi H, Erfanimanesh S, Pormohammad A, Hashemi A. Phenotypic and molecular detection of metallo-beta-lactamase genes among imipenem resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from patients with burn injuries. Arch Clin Infect Dis 2016; 11(4): e39036. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur A, Gupta V, Chhina D. Prevalence of metalo-β-lactamase-producing (MBL) Acinetobacter species in a tertiary care hospital. Iran J Microbiol 2014; 6: 22–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esther J, Edwin DH, Uma. Prevalence of carbapenem resistant non-fermenting gram negative bacterial infection and identification of carbapenemase producing NFGNB isolates by simple phenotypic tests. J Clin Diagn Res 2017; 11: DC10–DC13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaudhary AK, Bhandari D, Amatya J, Chaudhary P, Acharya B. Metallo-Beta-Lactamase producing gram-negative bacteria among patients visiting shahid Gangalal national heart centre. Austin J Microbiol 2016; 2: 1010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aghamiri S, Amirmozafari N, Fallah Mehrabadi J, Fouladtan B, Samadi Kafil H. Antibiotic resistance pattern and evaluation of metallo-beta lactamase genes including bla-IMP and bla-VIM types in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from patients in Tehran hospitals. ISRN Microbiol 2014; 2014: 941507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta V, Sidhu S, Chander J. Metallo-β-lactamase producing nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria: an increasing clinical threat among hospitalized patients. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2012; 5: 718–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acharya M, Joshi PR, Thapa K, Aryal R, Kakshapati T, Sharma S. Detection of metallo-β-lactamases-encoding genes among clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a tertiary care hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Res Notes 2017; 10: 718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farajzadeh Sheikh A, Shahin M, Shokoohizadeh L, Ghanbari F, Solgi H, Shahcheraghi F. Emerge of NDM-1-producing multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and co-harboring of carbapenemase genes in South of Iran. Iran J Public Health 2020; 49: 959–967. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wayne PA. (2019). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 29th ed. CLSI supplement M100S. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18: 268–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peleg AY, Franklin C, Bell JM, Spelman DW. Dissemination of the metallo-β-lactamase gene bla IMP-4 among gram-negative pathogens in a clinical setting in Australia. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41: 1549–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poirel L, Walsh TR, Cuvillier V, Nordmann P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2011; 70: 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sedighi M, Halajzadeh M, Ramazanzadeh R, Amirmozafari N, Heidary M, Pirouzi S. Molecular detection of β-lactamase and integron genes in clinical strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2017; 50: 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spilker T, Coenye T, Vandamme P, LiPuma JJ. PCR-based assay for differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from other Pseudomonas species recovered from cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 2074–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porbaran M, Habibipour R. Relationship between biofilm regulating operons and various β-Lactamase enzymes: analysis of the clinical features of infections caused by non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli (NF-GNB) from Iran. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2020; 14: 1723–1736. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bostanghadiri N, Ghalavand Z, Fallah F, Yadegar A, Ardebili A, Tarashi S, et al. Characterization of phenotypic and genotypic diversity of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strains isolated from selected hospitals in Iran. Front Microbiol 2019; 10: 1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grewal US, Bakshi R, Walia G, Shah PR. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli at a tertiary care hospital in Patiala, India. Niger Postgrad Med J 2017; 24: 121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu LF, Chen GS, Kong QX, Gao LP, Chen X, Ye Y, et al. Increase in the prevalence of resistance determinants to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in clinical Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolates in China. PLoS One 2016; 11(6): e0157693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung HS, Kim K, Hong SS, Hong SG, Lee K, Chong Y. The sul1 gene in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia with high-level resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Ann Lab Med 2015; 35: 246–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alcaraz E, Garcia C, Papalia M, Vay C, Friedman L, Passerini de Rossi B. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolated from patients exposed to invasive devices in a university hospital in Argentina: molecular typing, susceptibility and detection of potential virulence factors. J Med Microbiol 2018; 67: 992–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gheorghe I, Czobor I, Chifiriuc MC, Borcan E, Ghiţă C, Banu O, et al. Molecular screening of carbapenemase-producing gram-negative strains in Romanian intensive care units during a one year survey. J Med Microbiol 2014; 63: 1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Mahallawy HA, Hamid RMA, Hassan SS, Radwan S, Saber M. The increased frequency of carbapenem resistant non fermenting gram negative pathogens as causes of health care associated infections in adult cancer patients. J Cancer Ther 2015; 6: 881–888. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mirzaei B, Bazgir ZN, Goli HR, Iranpour F, Mohammadi F, Babaei R. Prevalence of multi-drug resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) phenotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii isolated in clinical samples from Northeast of Iran. BMC Res Notes 2020; 13: 380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tohamy ST, Aboshanab KM, El-Mahallawy HA, El-Ansary MR, Afifi SS. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens isolated from febrile neutropenic cancer patients with bloodstream infections in Egypt and new synergistic antibiotic combinations. Infect Drug Resist 2018; 11: 791–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gajdács M, Burián K, Terhes G. Resistance levels and epidemiology of non-fermenting gram-negative bacteria in urinary tract infections of inpatients and outpatients (RENFUTI): a 10-year epidemiological snapshot. Antibiotics (Basel) 2019; 8: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaleem F, Usman J, Hassan A, Khan A. Frequency and susceptibility pattern of metallo-beta-lactamase producers in a hospital in Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries 2010; 4: 810–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thapa P, Bhandari D, Shrestha D, Parajuli H, Chaudhary P, Amatya J, et al. A hospital based surveillance of metallo-beta-lactamase producing gram negative bacteria in Nepal by imipenem-EDTA disk method. BMC Res Notes 2017; 10: 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee K, Lee WG, Uh Y, Ha GY, Cho J, Chong Y, et al. VIM-and IMP-type metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. in Korean hospitals. Emerg Infect Dis 2003; 9: 868–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choudhary V, Pal N, Hooja S. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance pattern of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from clinical specimens in a tertiary care hospital. J Mahatma Gandhi Inst Med Sci 2019; 24: 19–22. [Google Scholar]