ABSTRACT

Introduction:In 2017, no indigenous malaria cases were reported in China, but imported malaria was a challenge for the elimination program. This study analyzed the status and trends of imported malaria in China from 2012 to 2018 to provide evidence for further strategies and adjustments to current interventions.

Methods: Data on individuals were collected from the Parasitic Diseases Information Reporting Management System (PDIRMS) from 2012 to 2018. Plasmodium species, case classification, temporal distribution, spatial distribution, and source of imported cases were analyzed to investigate imported malaria characteristics.

Results:In total, 21,376 malaria cases were recorded in the PDIRMS from 2012 to 2018. Among them, 20,938 (98.0%) cases were imported malaria cases (IMCs). The number and proportion of IMCs increased from 2012 (n=2,474, 91.0%) to 2018 (n=2,511, 99.7%). IMCs consisted of 13,510 (64.5%) P. falciparum, 4,803 (22.9%) P. vivax, 1,725 (8.2%) P. ovale, 376 (1.8%) P. malariae, 2 (0.01%) P. knowlesi, 348 (1.7%) mixed infections, and 174 (0.8%) clinically-diagnosed cases. The proportion of imported P. falciparum cases increased from 2012 (n=1403, 57.4%) to 2018 (n=1655, 66.0%), while imported P. vivax cases showed a decreasing trend from 2012 (n = 901, 43.7%) to 2018 (n=352, 14.0%). IMCs were mainly reported in Yunnan (n=2,922, 14.0%), Guangxi (n=2,827, 13.5%), and Jiangsu (2,067, 9.9%). IMCs were reported throughout the entire year, and the highest number of IMCs was reported in June 2013. IMCs originated from 67 countries from 4 continents, and the largest proportion were from Myanmar (n=3,081, 14.7%) and Ghana (n=2,704, 12.9%).

Conclusion and Implications for Public Health Practice: The total number of IMCs increased in China. Therefore, two actions are needed to continue the elimination of malaria in China: prevent re-establishment caused by imported P. vivax because Anopheles sinensis is still widely distributed; and ensure timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment to avoid fatal cases caused by imported P. falciparum.

INTRODUCTION

China has succeeded in controlling indigenous malaria and has reached milestones towards malaria elimination since the National Malaria Elimination Action Plan has launched in 2010 (1-3). In 2017, for the first time, no indigenous cases were reported in China (4). However, with increasing globalization, larger numbers of people go to or return from malaria endemic areas and present challenges to malaria elimination in China (5).

Imported malaria cases (IMCs) may increase risks in malaria-free localities where Anopheles mosquitoes still exist. In addition, severe malaria infections caused by Plasmodium falciparum are catastrophic if diagnosis and treatment are not timely.

In 2012, the Parasitic Diseases Information Reporting Management System (PDIRMS) was set up to determine whether every case was indigenous or imported. Therefore, the objective of this study was to characterize the epidemiological status and trends of IMCs from 2012 to 2018 to provide evidence-based data to support the adjustment of appropriate strategies and activities towards the achievement of malaria elimination not only in China but also in other countries with similar elimination processes.

METHODS

Data from 31 provincial-level administrative divisions (PLADs) were collected via the PDIRMS from 2012 to 2018 and carefully reviewed. Plasmodium species, case classification [indigenous①, imported②, or other (induced③, introduced④, relapse⑤ or recrudesce⑥)], and source of imported cases were analyzed to explore the characteristics of IMCs. Clinically-diagnosed cases⑦ and laboratory-confirmed cases⑧ were included in this analysis. Data from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan were excluded from the study. Moreover, data from foreign nationals were not concluded. Statistical analysis was performed using the chi-square test for trends by software SPSS ( version 21.0, IBM Corp., New York, US), and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In total, 21,376 malaria cases were recorded in the PDIRMS from 2012 to 2018. Among them, 20,938 (98.0%) cases were IMCs. The number and proportion of IMCs increased from 2012 (n=2,474, 91.0%) to 2018 (n=2,511, 99.7%) with statistical significance (evaluated by chi-square test for trends, χ2 = 435.423, p < 0.001). IMCs consisted of 20,764 laboratory-confirm cases and 174 clinically-diagnosed cases. The laboratory-confirmed cases consisted of 13,510 (64.5%) P. falciparum cases, 4,803 (22.9%) P. vivax cases, 1,725 (8.2%) P. ovale cases, 376 (1.8%) P. malariae cases, 2 (0.01%) P. knowlesi cases, 348 (1.7%) mixed infection cases (Table 1). Among these cases, the proportion of imported P. falciparum cases increased from 2012 (n=1,403, 57.4%) to 2018 (n=1,655, 66.0%), while imported P. vivax cases decreased from 2012 (n=901, 43.7%) to 2018 (n=352, 14.0%). In addition, imported P. malariae and P. ovale cases also increased during the same timeframe. In 2012, the proportion of P. malariae and P. ovale cases was 2.3% (n=56), while in 2018, this proportion peaked at 18.0% (n=453). Most IMCs were male (n=19,877, 94.9%), and 1,061 cases (5.1%) were female. The highest number of IMCs was observed in the age group of 46 to 50 years, and most IMCs occurred in migrant workers (n=14,300, 68.3%).

Table 1. Clinically-diagnosed and laboratory-confirmed imported malaria cases in China (2012–2018).

| Year | Subtotal | Laboratory-confirmed cases | Clinically-diagnosed cases | |||||

| P. vivax | P. falciparum | P. ovale | P. malariae | P. knowlesi | Mixed | |||

| * The number of imported P. ovale and P. malariae was not counted separated, so herein we provide the total number of P. ovale and P. malariae. | ||||||||

| 2012 | 2,474 | 901 | 1,403 | 56* | 0 | 0 | 39 | |

| 2013 | 4,042 | 859 | 2,899 | 133 | 51 | 0 | 65 | 35 |

| 2014 | 3,022 | 798 | 1,876 | 231 | 53 | 1 | 44 | 19 |

| 2015 | 3,077 | 779 | 1,895 | 266 | 65 | 0 | 55 | 17 |

| 2016 | 3,139 | 622 | 2,066 | 315 | 64 | 0 | 59 | 14 |

| 2017 | 2,672 | 496 | 1,716 | 350 | 65 | 1 | 35 | 9 |

| 2018 | 2,511 | 348 | 1,655 | 374 | 78 | 0 | 51 | 5 |

| Total | 20,938 | 4,803 | 13,510 | 1,725 | 376 | 2 | 348 | 174 |

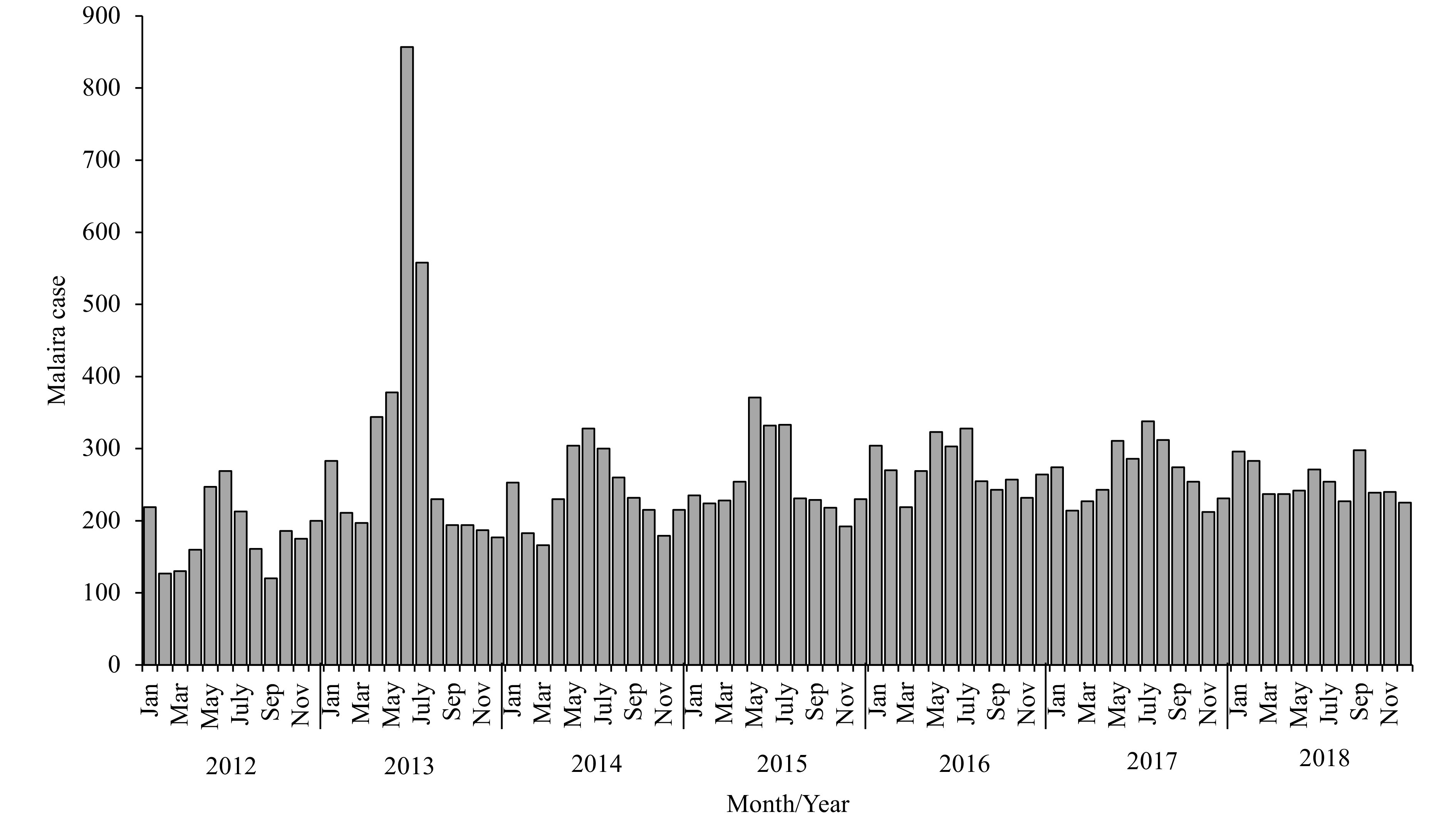

IMCs were mainly reported in the PLADs of Yunnan (n=2,922, 14.0%), Guangxi (n=2,827, 13.5%), and Jiangsu (n=2,067, 9.9%) (Table 2). The distribution of IMCs broadened with cases reported in 618 counties in 2012 and 688 counties in 2018. The temporal distribution showed that IMCs were reported throughout the entire year, and the highest number of IMCs was reported in June 2013 (n=857) (Figure 1).

Table 2. Imported malaria cases in 31 provincial-level administrative divisions (PLADs) in China (2012–2018).

| PLADs | Total cases | Imported cases | Proportion of imported cases (%) in the whole country | |

| Number | Proportion (%) | |||

| Yunnan | 3,285 | 2,922 | 88.9 | 14.0 |

| Guangxi | 2,828 | 2,827 | 99.9 | 13.5 |

| Jiangsu | 2,070 | 2,067 | 99.9 | 9.9 |

| Sichuan | 1,697 | 1,697 | 100.0 | 8.1 |

| Henan | 1,285 | 1,285 | 100.0 | 6.1 |

| Shandong | 1,283 | 1,282 | 99.9 | 6.1 |

| Zhejiang | 1,241 | 1,241 | 100.0 | 5.9 |

| Guangdong | 1,038 | 1,035 | 99.7 | 4.9 |

| Hunan | 969 | 964 | 99.5 | 4.6 |

| Hubei | 884 | 875 | 99.0 | 4.2 |

| Anhui | 876 | 845 | 96.5 | 4.0 |

| Fujian | 637 | 637 | 100.0 | 3.0 |

| Beijing | 561 | 561 | 100.0 | 2.7 |

| Shannxi | 424 | 424 | 100.0 | 2.0 |

| Liaoning | 355 | 353 | 99.4 | 1.7 |

| Hebei | 323 | 323 | 100.0 | 1.5 |

| Jiangxi | 304 | 304 | 100.0 | 1.5 |

| Shanghai | 284 | 284 | 100.0 | 1.4 |

| Chongqing | 209 | 209 | 100.0 | 1.0 |

| Gansu | 162 | 162 | 100.0 | 0.8 |

| Guizhou | 150 | 150 | 100.0 | 0.7 |

| Jilin | 105 | 105 | 100.0 | 0.5 |

| Shanxi | 93 | 93 | 100.0 | 0.4 |

| Hainan | 81 | 80 | 98.8 | 0.4 |

| Tianjin | 62 | 62 | 100.0 | 0.3 |

| Heilongjiang | 41 | 41 | 100.0 | 0.2 |

| Xinjiang | 37 | 37 | 100.0 | 0.1 |

| Ningxia | 29 | 29 | 100.0 | 0.1 |

| Inner Monglia | 19 | 19 | 100.0 | 0.1 |

| Qinghai | 14 | 14 | 100.0 | 0.1 |

| Tibet | 30 | 9 | 30.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 21,376 | 20,936 | 97.9 | 100.0 |

Figure 1.

Temporal distribution of imported malaria cases in China (2012–2018).

IMCs originated from 67 countries from 4 continents, and among them, 16,720 cases (79.9%) originated from Africa, mainly central and western Africa, which accounted for 33.5% (n=7,007) and 32.5% (n=6,806) of all IMCs, respectively. IMCs from Africa in this time period showed an increasing trend with 58.8% in 2012 (n=1,454) and 90.4% in 2018 (n=2,470). The imported P. falciparum cases from Africa also showed an increasing trend. In 2012, 32 African countries reported 1,177 P. falciparum cases, while in 2018, 35 African countries reported 1,641 P. falciparum cases. The cases imported from Africa were mainly from Ghana (n=2,704, 12.9%), Angola (n=2,085, 10.0%), and Nigeria (n=1,939, 9.3%) (Table 3).

Table 3. Source of imported cases reported in China (2012–2018).

| Regions | Country | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Total |

| Africa | 1,454 | 3,243 | 2,295 | 2,487 | 2,689 | 2,282 | 2,270 | 16,720 | |

| Southeast Africa | 196 | 311 | 380 | 457 | 541 | 436 | 395 | 2,716 | |

| Ethiopia | 38 | 62 | 118 | 150 | 148 | 113 | 95 | 724 | |

| Mozambique | 22 | 48 | 68 | 75 | 84 | 103 | 104 | 504 | |

| Uganda | 16 | 28 | 28 | 53 | 139 | 66 | 41 | 371 | |

| Tanzania | 13 | 34 | 41 | 52 | 49 | 46 | 58 | 293 | |

| Sudan | 63 | 72 | 44 | 44 | 7 | 15 | 10 | 255 | |

| Zambia | 17 | 37 | 42 | 48 | 47 | 30 | 33 | 254 | |

| Kenya | 7 | 6 | 11 | 9 | 14 | 23 | 13 | 83 | |

| Malawi | 9 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 71 | |

| Madagascar | 5 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 45 | |

| South Sudan | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 20 | 9 | 10 | 45 | |

| Rwanda | 2 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 39 | |

| Zimbabwe | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 13 | |

| Djibouti | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 8 | |

| Egypt | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| Eritrea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Somalia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| West Africa | 641 | 1,870 | 879 | 723 | 828 | 950 | 915 | 6,806 | |

| Ghana | 235 | 1349 | 188 | 172 | 241 | 347 | 172 | 2,704 | |

| Nigeria | 207 | 225 | 341 | 283 | 273 | 286 | 324 | 1,939 | |

| Guinea | 58 | 75 | 64 | 98 | 72 | 80 | 129 | 576 | |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 18 | 16 | 41 | 64 | 104 | 97 | 127 | 467 | |

| Liberia | 44 | 86 | 88 | 34 | 39 | 61 | 56 | 408 | |

| Sierra Leone | 43 | 55 | 53 | 34 | 43 | 44 | 63 | 335 | |

| Benin | 5 | 22 | 33 | 10 | 17 | 9 | 12 | 108 | |

| Togo | 2 | 24 | 50 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 105 | |

| Mali | 17 | 14 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 84 | |

| Burkina Faso | 6 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 33 | |

| Niger | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 | 4 | 3 | 25 | |

| Senegal | 5 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 16 | |

| Mauritania | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Gambia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Central Africa | 550 | 1,038 | 1,015 | 1,283 | 1,292 | 882 | 947 | 7,007 | |

| Angola | 151 | 437 | 272 | 416 | 410 | 192 | 207 | 2,085 | |

| Equatorial Guinea | 247 | 300 | 287 | 272 | 185 | 132 | 115 | 1,538 | |

| Cameroon | 17 | 101 | 175 | 248 | 242 | 190 | 159 | 1,132 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 47 | 64 | 118 | 175 | 244 | 151 | 236 | 1,035 | |

| Republic of Congo | 33 | 53 | 83 | 101 | 154 | 119 | 98 | 641 | |

| Gabon | 35 | 42 | 34 | 43 | 37 | 53 | 73 | 317 | |

| Chad | 11 | 36 | 38 | 25 | 9 | 13 | 30 | 162 | |

| The Central African Republic | 9 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 28 | 25 | 82 | |

| Burundi | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 15 | |

| South Africa | 11 | 21 | 17 | 12 | 14 | 9 | 5 | 89 | |

| South Africa | 11 | 20 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 8 | 5 | 84 | |

| Namibia | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | |

| Comoros | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| North Africa | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 23 | |

| Libya | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 17 | |

| Algeria | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Africa (Other regions) | 51 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 79 | |

| Asia | 955 | 774 | 706 | 566 | 420 | 359 | 219 | 3,999 | |

| Southeast Asia | 906 | 736 | 674 | 548 | 392 | 291 | 192 | 3,739 | |

| Myanmar | 766 | 605 | 495 | 477 | 326 | 245 | 167 | 3,081 | |

| Indonesia | 36 | 71 | 142 | 35 | 27 | 18 | 7 | 336 | |

| Laos | 37 | 38 | 18 | 12 | 27 | 13 | 5 | 150 | |

| Cambodia | 57 | 19 | 9 | 17 | 6 | 14 | 11 | 133 | |

| Vietnam | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | |

| Thailand | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |

| Malaysia | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| The Philippines | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| Timor-Leste | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| East Asia | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Democratic People’s Republic of Korea | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Republic of Korea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| South Asia | 47 | 37 | 32 | 17 | 26 | 67 | 26 | 252 | |

| Pakistan | 31 | 22 | 17 | 10 | 18 | 63 | 22 | 183 | |

| India | 14 | 15 | 15 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 65 | |

| Afghanistan | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Nepal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Bangladesh | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| South America | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 30 | |

| Guyana | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 18 | |

| Venezuela | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | |

| Brazil | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| Ecuador | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Surinam | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Oceania | 6 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 16 | 21 | 15 | 75 | |

| Papua New Guinea | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 14 | 19 | 15 | 70 | |

| Solomon Islands | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | |

| Unknown sources | 58 | 12 | 10 | 20 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 113 | |

| Total | 2,474 | 4,042 | 3,021 | 3,077 | 3,139 | 2,672 | 2,511 | 20,936 |

The cases from another major infection source, namely, Southeast Asia, gradually declined. In this area, 3,999 cases (19.1%) were reported in 2012-2018 with a 77.1% decrease from 2012 (n=955) to 2018 (n=219). In Myanmar, the major source of imported cases in Southeast Asia, the number of P. vivax cases greatly decreased. In 2012, there were 554 P. vivax cases imported from Myanmar, accounting for 22.4% of the IMCs in the same year. In 2018, however, there were only 154 cases imported from Myanmar, accounting for only 6.1% of the IMCs. Moreover, 5 countries from South America and 2 countries from Oceania reported 30 and 75 cases, respectively.

From 2012 to 2018, China reported 111 malaria death cases (0.5%, 111/20,936) among the IMCs, and most of these cases died of P. falciparum infection (n=108, 97.3%), and China also reported 3 unclassified cases. The deaths mainly reported in Sichuan (n=13, 11.7%), Henan (n=12, 10.8%), and Beijing (n=12, 10.8%). The highest number of deaths occurred in 2014 (n=25).

DISCUSSION

For countries that are approaching or have achieved elimination, imported malaria presents a high risk for resurgence or re-establishment (6-7). In 2018, Hunan Province reported 4 introduced cases (P. vivax, first generation), which prompted the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) staff to strengthen the sensitivity of the surveillance system (8). Since 2012, the proportion of IMCs has increased due to the increased numbers of Chinese workers going to and coming back from abroad. According to data reported by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the number of migrant workers was 606,000 in 2018, which increased by 16.6% compared to that in 2012 (505,563).

The increasing trend of imported P. falciparum cases from 2012 to 2018 may be explained by the increasing number of migrant workers who travelled to or returned from Africa. The number of imported P. vivax cases increased before 2012 (9) but decreased after 2012. This decreasing trend may have been due to the decline of malaria cases imported from Southeast Asia, especially Myanmar. Several factors have contributed to the reduction of P. vivax in Myanmar. First, the number of P. vivax cases in Myanmar continues to decline, and the number of P. vivax cases decreased from 53,351 in 2007 to 29,944 in 2017 (10-11). Second, Yunnan Province, which neighbors Myanmar, adopted a “three defense line” strategy in the border areas to carry out joint prevention and control with Myanmar to strengthen the surveillance of IMCs (12). Therefore, the number of P. vivax cases reported by the Yunnan Province also declined significantly with a 76.8% reduction from 2012 (599 cases) to 2018 (137 cases). Third, the flow of Chinese nationals changed direction, especially for those in the border areas of Yunnan Province (13).

With regard to the increasing number of P. malariae and P. ovale cases, the increasing number of overseas workers may be one of the factors contributing to this trend as well as the establishment of the provincial reference laboratories. China has established 24 provincial reference laboratories for all the endemic provinces, which have achieved case detection and reconfirmation using polymerase chain reaction and microscopy within 3 day after reporting through the PDIRMS (14). The capacity of the CDC staff to focus on microscopy has strengthened through training by the External Competency Assessment of Malaria Microscopists (ECAMM) held by the World Health Organization (WHO) since 2015. Currently, 19 CDC staff members have obtained first-level certification, and an additional 13 CDC staff members have obtained second-level certification (4).

This study indicated that the number of imported P. vivax cases decreased, while imported P. falciparum cases increased. Therefore, accurate diagnosis and prompt investigation and response need to be strengthened as well as implementation of mobile population-specific measures, especially at the China-Myanmar border to prevent re-establishment caused by imported P. vivax cases (15). Moreover, timely and appropriate treatment by medical staff should be improved to avoid fatal malaria cases caused by imported P. falciparum.

This study is subject to at least a few limitations. First, not all IMCs had exact epidemiological information in 2012−2018. Second, there were 113 unknown cases imported from abroad. Third, not all IMCs were confirmed by laboratory methods as 174 clinically-diagnosed cases were included in this study. Finally, an accurate number of P. ovale and P. malariae cases was not obtained in 2012.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the staff members of the provincial and county Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in China for assistance.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the key techniques in collaborative prevention and control of major infectious diseases in the Belt and Road (2018ZX10101002-004).

Footnotes

Indigenous case: a case contracted locally with no evidence of importation and no direct link to transmission from an imported case. In this study, an indigenous case refers to malaria acquired by mosquito transmission in the People’s Republic of China.

Imported case: a malaria case or infection in which the infection was acquired outside the area in which it was diagnosed. Here, it refers to the patient who acquired the illness from a known malaria-prevalent region outside the People’s Republic of China.

Induced case: a case in which the origin of the illness can be traced to a blood transfusion or other form of parenteral inoculation of the parasite but not to transmission by a natural mosquito-borne inoculation.

Introduced case: a case contracted locally with strong epidemiological evidence linking it directly to a known imported case (first-generation local transmission).

Relapse case: a malaria case attributed to activation of hypnozoites of P. vivax or P. ovale acquired previously.

Recrudescent case: recurrence of asexual parasitaemia of the same genotype(s) that caused the original illness due to incomplete clearance of asexual parasites after antimalarial treatment.

Clinically diagnosed case: an individual with malaria-related symptoms (fever [axillary temperature ≥37.5 °C], chills, severe malaise, headache, or vomiting) at the time of examination.

Laboratory-diagnosed case: a clinical case confirmed by microscopy, polymerase chain reaction, or rapid diagnostic tests in the laboratory.

References

- 1.Feng J, Xiao HH, Xia ZG, Zhang L, Xiao N Analysis of malaria epidemiological characteristics in the People’s Republic of China, 2004-2013. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(2):293–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng J, Tu H, Zhang L, Zhang SS, Jiang S, Xia ZG, et al Mapping transmission foci to eliminate malaria in the People’s Republic of China, 2010-2015: a retrospective analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:115. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3018-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng J, Zhou SS From control to elimination: the historical retrospect of malaria control and prevention in China. Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis. 2019;37(5):505–13. doi: 10.12140/j.issn.1000-7423.2019.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng J, Zhang L, Huang F, Yin JH, Tu H, Xia ZG, et al Ready for malaria elimination: zero indigenous case reported in the People’s Republic of China. Malar J. 2018;17(1):315. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2444-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng J, Xia ZG, Vong S, Yang WZ, Zhou SS, Xiao N Preparedness for malaria resurgence in China: case study on imported cases in 2000-2012. Adv Parasitol. 2014;86:231–65. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800869-0.00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dharmawardena P, Premaratne RG, De AW Gunasekera WMKT, Hewawitarane M, Mendis K, Fernando D Characterization of imported malaria, the largest threat to sustained malaria elimination from Sri Lanka. Malar J. 2015;14:177. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0697-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Yu WQ, Shi H, Yang ZZ, Xu JN, Ma YJ Historical survey of the kdr mutations in the populations of Anopheles Sinensis in China in 1996-2014 . Malar J. 2015;14:120. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0644-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Feng J, Zhang SS, Xia ZG, Zhou SS Epidemiological characteristics of malaria and the progress towards its elimination in China in 2018. Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis. 2019;37(3):241–7. doi: 10.12140/j.issn.1000-7423.2019.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng J, Xiao HH, Zhang L, Yan H, Feng XY, Fang W, et al The plasmodium vivax in China: decreased in local cases but increased imported cases from southeast Asia and Africa . Sci Rep. 2015;5:8847. doi: 10.1038/srep08847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. World malaria report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2018/en/.

- 11.World Health Organization. World malaria report 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241563697/en/.

- 12.Feng J, Liu J, Feng XY, Zhang L, Xiao HH, Xia ZG Towards malaria elimination: monitoring and evaluation of the "1-3-7" approach at the China-Myanmar Border. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95(4):806–10. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Feng J, Tu H, Xia ZG, Zhou SS Challenges in malaria elimination: the epidemiological characteristics of Plasmodium vivax in China from 2011 to 2018 . Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis. 2019;37(5):532–8. doi: 10.12140/j.issn.1000-7423.2019.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin JH, Yan H, Huang F, Li M, Xiao HH, Zhou SS, et al Establishing a China malaria diagnosis reference laboratory network for malaria elimination. Malar J. 2015;14:40. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0556-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen TM, Zhang SS, Feng J, Xia ZG, Luo CH, Zeng XC, et al Mobile population dynamics and malaria vulnerability: a modelling study in the China-Myanmar border region of Yunnan Province, China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7:36. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0423-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]