Abstract

Background

Previous COVID-19 pandemic research has focused on assessing the severity of psychological responses to pandemic-related stressors. Little is understood about (a) resilience as a mental health protective factor during these stressors, and (b) whether families from Eastern and Western cultures cope differently. This study examines how individual resilience and family resilience moderate the associations between pandemic-related stressors and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in two culturally distinct regions.

Methods

A total of 1,039 adults (442 from Minnesota, United States, and 597 from Hong Kong) living with at least one family member completed an online survey about COVID-19-related experiences, mental health, individual resilience and family resilience from May 20 to June 30, 2020. Predictors of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms were examined separately using hierarchical regression analyses.

Results

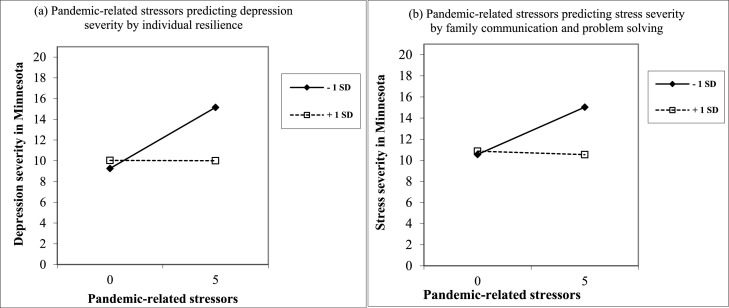

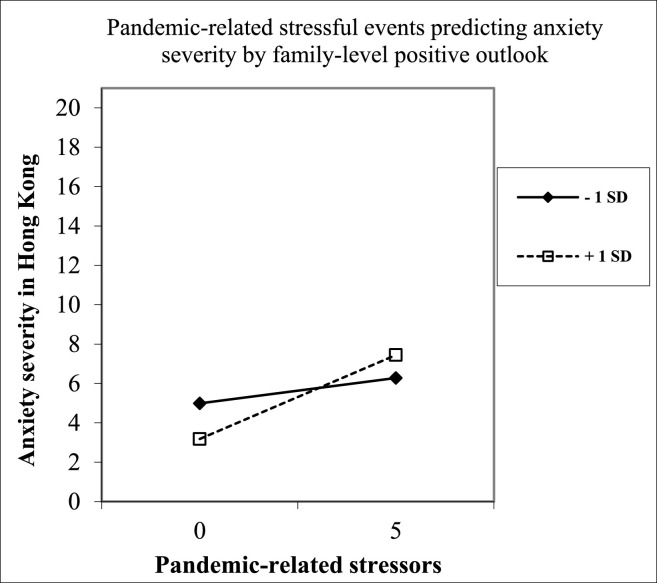

In both regions, pandemic-related stressors predicted higher symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Individual resilience and two domains of family resilience were associated with positive mental health. In Minnesota, higher levels of individual resilience buffered the negative relationship between pandemic-related stressors and depressive symptoms; higher levels of family communication and problem solving also buffered the negative relationship between pandemic-related stressors and stress symptoms. In Hong Kong, higher family-level positive outlook magnified the negative relationship between pandemic-related stressors and anxiety symptoms.

Conclusions

Individual and family resilience is protective against the adverse psychological effects of pandemic stressors, but they vary across cultures and as exposure to pandemic-related stressors increases.

Keywords: COVID-19, Individual resilience, Family resilience, Mental health

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created a public health emergency and produced a profound ripple effect on individuals, family systems, communities, and societies through the world. As the COVID-19 pandemic progressed, governments have launched lockdown policies and emphasized the need for social distancing measures to mitigate the rapid transmission of COVID-19 (World Health Organization, 2020). As a result, many individuals and families are forced to stay at home and are physically cut off from extrafamilial supports in the early outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic. While virtual connections may help maintain some social relations, these social distancing measures seem likely to produce a significant loss of social support from outside the home. Although lockdowns might provide opportunities for renewing connections with family members, interpersonal friction could also be magnified when staying in close proximity for an extended period (Lee, 2020). Altogether, the uncertainty and social isolation arising from the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to an unprecedented mental health crisis. Indeed, recent systematic reviews of population-based studies worldwide consistently demonstrate high rates of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms during this pandemic (Cooke et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021). However, some individuals and families may be at greater risk for mental health symptoms depending upon the extent of their exposure to pandemic-related stressors. Those working in healthcare or other “frontline” positions have faced elevated stress, as have those experiencing pandemic-related unemployment as well as illness and death of family members (Amerio et al., 2020; Connor et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021).

1.1. Families from different cultures

Drawing upon Bronfenbrenner's (1979) Ecological Framework, individual adjustment is influenced by the interaction processes with both family and sociocultural contexts during the pandemic. The family adjustment and adaptation response (FAAR) Model posits that individual and family stress responses are moderated by the perception of the stressor and the resources available to the family (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983). At the family level, the FAAR Model suggests that family systems with resources, such as collaborative problem solving skills and a positive outlook, may buffer the negative impact of pandemic-related stressors on family processes and individual adjustment. However, family discord and marital conflicts may also threaten individual and family well-being (Lee, 2020). At the cultural level, individuals from various sociocultural contexts may adapt various coping strategies when facing pandemic-related stressors. Individuals from individualistic, Western cultures tend to embrace independent self-construal (i.e., autonomy and separation), while individuals from collectivistic, Eastern cultures tend to embrace interdependent self-construal (i.e., connecting with others; Markus and Kitayama, 1991). Given these differences, it is possible that individuals and families representing these cultures will demonstrate unique responses and coping strategies when faced with pandemic-related stressors.

1.2. Individual resilience and family resilience

Both individual resilience and family resilience has been identified to support positive coping with adversity. Individual resilience is a dynamic process in which individuals are able to adaptive positively after exposure to adversity or trauma (Lutha and Cicchetti, 2000). In the face of a pandemic, high individual resilience serves to buffer stress and psychological distress throughout the crisis (Hou et al., 2021; Prime et al., 2020; Riehm et al., 2021). Past research has focused on evaluating the impact of individual resilience on mental health following a major public health event (e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2003; Bonanno et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2004). Recent studies explored the relationships between individual resilience and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Havnen et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2021; Riehm et al., 2021). For example, adults in Western societies such as the United States and Norway reporting low resilience experienced marked increases in mental distress during the pandemic (Havnen et al., 2020; Riehm et al., 2021). Resilience was associated with lower levels of anxiety in Hong Kong (Hou et al., 2021).

Family beliefs, interactions, and resources may support family adjustment and adaptations during the pandemic (Prime et al., 2020; Walsh, 2020). Family resilience is as an active process of personal and relational transformation through which family members emerge stronger and more resourceful through their shared efforts in confronting family challenges (Walsh, 1996). Family resilience focuses on three key processes when dealing with challenges, including family belief systems (i.e., meaning making and positive family outlook), family communication processes (i.e., collaborative problem solving) and organization processes (i.e., family connectedness, flexibility to adapt, and family resources; Walsh, 2016). Emerging evidence indicated that family resilience buffered the association between family stress and adjustment of single parent families in an Eastern culture (i.e., Korea; Hyun, 2007). However, no empirical studies to date have investigated how family resilience processes may facilitate or hinder individuals’ and family units’ ability to cope with social disruption during the pandemic.

Previous research has shown that family coping styles may vary across cultures. For example, a review on culture and social support provided evidence that Asians or Asian Americans are more reluctant than European Americans to explicitly ask for support from close others (Kim et al., 2008). Furthermore, we are not aware of any studies that have simultaneously examined whether individual and family resilience factors moderate the association between stressors and mental health of individuals facing a public health emergency such as a pandemic. Thus, a better understanding of how resilience may function across cultures will facilitate the design and implementation of timely, culturally-sensitive psychoeducation and/or interventions to support mental health when facing crises such as pandemics.

1.3. The present study

To understand the intersectional influences of families and cultures on pandemic-related coping, samples were recruited from the United States and Hong Kong, representing individualistic and collectivistic societies respectively (Gardner et al., 1999; Hofstede et al., 2010). Rather than surveying the U.S. nationally, we selected a single state, Minnesota, to sample. Because of the wide variability in COVID cases across states as well as state-level social distancing mandates, a focus on a single state allowed for greater consistency in these variables. The two regions surveyed for the current study share some similarities and many differences that may influence individuals’ experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic. Minnesota and Hong Kong are of approximately the same population size (5.6 to 7 million at the time of the study), and each launched a social distancing policy in approximately the same timeframe. Notably, the course of the pandemic progressed differently in the two regions. In Minnesota, the first COVID-19 case started in early March, with an average of 436 new daily COVID-19 cases (range = 143–984) between mid-May and June. In Hong Kong, the first COVID-19 case started in late January, with fewer than 30 new daily COVID cases between mid-May and June.

The two regions demonstrate significant social and cultural differences as well as distinct experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of these many layers of regional variation, our focus was not on detecting differences in resilience processes between the two regions. Any differences that emerged would be difficult to interpret due to challenges in disentangling cultural and pandemic-related factors as well as a potential lack of measurement equivalence of key constructs across the regions. Instead, we sought to simultaneously understand how resilience factors may support individuals and their families within each region while considering the unique cultural context and pandemic experiences of each region.

Specifically, our goals for this study were to (a) examine the association between pandemic-related stressors and mental health (i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress severity) among adults in Minnesota and Hong Kong; and (b) explore whether individual resilience and family resilience moderates the relationship. We hypothesized that more pandemic-related stressors would be associated with poorer mental health (H1); higher individual resilience and family resilience, respectively, would be associated with better mental health (H2, H3); individual resilience and family resilience, respectively, would buffer the negative relationship between pandemic-related stressors and mental health (H4, H5).

2. Methods

2.1. Procedures

Participants eligible for this study were (a) adults aged 18 or above, (b) currently living in Minnesota or Hong Kong, (c) living with at least one family member, and (d) practicing social distancing due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the past or currently. Participants were excluded if they were living on their own or living with non-family members only. Social distancing refers to the mandatory or voluntary practice of reducing physical contact with people outside of the home (e.g., in social, work, or school settings) to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19. Only one member from each household was encouraged to participate. Convenience and snowball sampling was used to recruit participants from both regions from May 20 to June 30, 2020. Study information about family health promotion under COVID-19 was advertised on local Facebook groups and via university networks in Minnesota and Hong Kong, respectively. Participants were directed to a link for the Qualtrics survey. IP addresses were checked to confirm the unique identity and location of participants. Participants could opt in for a random drawing of a gift card upon completion of the survey. This study was approved by the authors’ university ethics review boards in Minnesota and Hong Kong.

2.2. Participants

Potential participants made 1482 clicks on the link to the survey webpage (i.e., 603 from Minnesota and 879 from Hong Kong). Among them, 1039 participants (442 from Minnesota and 597 from Hong Kong) met the eligibility criteria and completed COVID-19 experiences and mental health measures; these participants were included in the final dataset for analysis. Of note, 5% of participants had partial completion of the survey (i.e., 21 from Minnesota and 31 from Hong Kong), which we speculate was primarily due to respondent fatigue. There were no significant differences in demographics between full and partial responses in both regions. Participants who partially completed the survey were retained in the sample for data analyses. Minimal missing data (<3% of dataset) were observed and imputed using multiple imputation.

Table 1 shows the demographics of the samples from each region. For the Minnesota sample (N = 442), respondents were an average age of 41 years old (SD = 12.86), predominately females (86%) and White non-Hispanic (80%). A majority of respondents (77%) had completed bachelor's degrees or above. Respondents were predominately middle-class, married or cohabitating (79%) and living with children (61%). More than half (53%) of respondents were caregivers for children or grandchildren, while 10% were caregivers for adult family members. Of note, the Minnesotan sample was slightly different from overall state demographics (United States Census Bureau, 2019), with a similar proportion of White non-Hispanic and age group distribution, but slightly more educated than the state average for the adult population and had greater representation of females.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, Pandemic Exposure, Mental Health, and Resilience by Region.

| Minnesota (n = 442) |

Hong Kong (n = 597) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristics | Range | n | % | n | % |

| Female | 382 | 86.4 | 428 | 71.7 | |

| Age (M, SD) | 41.89 | 12.86 | 31.6 | 12.51 | |

| 18–39 | 221 | 50.0 | 455 | 76.2 | |

| 40–59 | 171 | 38.7 | 122 | 20.4 | |

| 60–85 | 50 | 11.3 | 20 | 3.4 | |

| White non-Hispanic | 355 | 80.3 | – | – | |

| Married / cohabitated | 350 | 79.2 | 185 | 31.0 | |

| Bachelor degree or above | 342 | 77.4 | 256 | 42.9 | |

| Household characteristics | |||||

| Household income below poverty line | 24 | 5.4 | 87 | 14.6 | |

| Household income above 75th percentile | 214 | 48.4 | 89 | 14.9 | |

| Primary caregivers for children or grandchildren | 235 | 53.2 | 118 | 19.8 | |

| Primary caregivers for adult family members | 44 | 10.0 | 125 | 20.9 | |

| Number of people living at home (M, SD) | 3.54 | 1.48 | 3.56 | 1.16 | |

| Number of pandemic-related stressors | |||||

| 0 | 3 | 0.7 | 97 | 16.2 | |

| 1 | 36 | 8.1 | 216 | 36.2 | |

| 2 | 176 | 39.8 | 205 | 34.3 | |

| 3 | 153 | 34.6 | 64 | 10.7 | |

| 4+ | 74 | 16.7 | 15 | 2.5 | |

| Pandemic-related stressors | |||||

| Currently practicing social distancing/quarantining | 400 | 90.5 | 216 | 36.2 | |

| Family members inside/outside home experiencing or suspected of having symptoms of COVID-19 | 124 | 28.1 | 47 | 7.9 | |

| Family members at home working in high risk job | 130 | 29.4 | 115 | 19.3 | |

| Family members working from home in response to COVID-19 | 349 | 79.0 | 310 | 51.9 | |

| Family members experiencing reduced employment | 151 | 34.2 | 193 | 32.3 | |

| Current mental health (DASS-21) | |||||

| Depression(M, SD) | 0–21 | 6.58 | 4.89 | 5.07 | 4.59 |

| Normal | 0–4 | 175 | 39.6 | 326 | 54.6 |

| Mild | 5–6 | 78 | 17.6 | 96 | 16.1 |

| Moderate | 7–10 | 102 | 23.1 | 95 | 15.9 |

| Severe | 11–13 | 42 | 9.5 | 41 | 6.9 |

| Extremely severe | 14–21 | 45 | 10.2 | 39 | 6.5 |

| Anxiety(M, SD) | 0–21 | 3.30 | 3.87 | 3.70 | 4.21 |

| Normal | 0–3 | 289 | 65.4 | 370 | 62.0 |

| Mild | 4–5 | 47 | 10.6 | 77 | 12.9 |

| Moderate | 6–7 | 38 | 8.6 | 56 | 9.4 |

| Severe | 8–9 | 28 | 6.3 | 25 | 4.2 |

| Extremely severe | 10–21 | 40 | 9.0 | 69 | 11.6 |

| Stress(M, SD) | 0–21 | 7.73 | 5.04 | 5.79 | 4.86 |

| Normal | 0–7 | 100 | 22.6 | 229 | 38.4 |

| Mild | 8–9 | 66 | 14.9 | 100 | 16.8 |

| Moderate | 10–12 | 61 | 13.8 | 86 | 14.4 |

| Severe | 13–16 | 69 | 15.6 | 59 | 9.9 |

| Extremely severe | 17–21 | 146 | 33.0 | 123 | 20.6 |

| Individual resilience (CD-RISC10) (M, SD) | 0–40 | 26.71 | 5.83 | 22.66 | 6.31 |

| Family resilience (FRAS) (M, SD) | |||||

| Communication and collaborative problem-solving | 23–92 | 71.18 | 10.58 | 64.28 | 10.89 |

| Maintaining a family-level positive outlook | 6–23 | 19.45 | 2.65 | 17.61 | 3.64 |

Note. CD-RISC-2 = Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale–2; DASS-21 = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale–21; FRAS-32 = Family Resilience Assessment Scale–32.

For the Hong Kong sample (N = 597), 72% of respondents were females and an average age of 32 years old (SD = 12.51). Nearly half of respondents (43%) had bachelor's degrees and above. Respondents were predominately never married (67%), living with parents (69%) and siblings (42%). Similar proportions of respondents reported that they were caregivers for children or grandchildren (20%), and adult family members (21%). Of note, the Hong Kong sample demonstrated some differences from the overall region demographics (Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department, 2020), with a higher proportion of younger adults than the regional distribution, greater education than the regional average, and greater representation of females.

2.3. Study measures

English and Chinese survey batteries were provided to participants in Minnesota and Hong Kong respectively. Demographics and validated scales were used to measure pandemic-related stressors, mental health, individual resilience, and family resilience.

2.3.1. Demographics

Participants provides demographics, including age, gender, ethnicity (for the Minnesota sample), marital status, annual household income, information about family members living in the same household, and caregiving responsibilities for children, grandchildren, or adults at home.

2.3.2. Pandemic-related stressors

Pandemic-related stressors were measured using five items: (a) currently practicing social distancing or quarantining, (b) family members inside/outside the home experiencing or suspected of having symptoms of COVID-19, (c) family members inside the home working in healthcare or other high risk jobs for contracting COVID-19, (d) family members working from home in response to COVID-19, and (e) family members experiencing reduced employment (e.g., job loss, limited working hours, or not working due to safety concern) as a result of COVID-19. These items were selected based on existing literature identifying common pandemic-related stressors (Connor et al., 2020; Prime et al., 2020). An overall pandemic-related stressors score was created by summing the number of pandemic-related stressors experienced.

2.3.3. Depression, anxiety and stress

Symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress were measured using the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995; Taouk et al., 2001). Each item was rated on a four-point Likert scale to indicate the severity or frequency of experiencing each state over the past week. Total scores were obtained by summing the items scores of each subscale; we then categorized participants into conventional severity labels (i.e., normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe) based on normed cut-off scales (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1996). The Chinese version of DASS-21 had been validated previously and has an established corresponding 3-factor structure in a Hong Kong sample (Moussa et al., 2001). The respective internal consistency for depression, anxiety, and stress subscales were α = 0.90, 0.84, and 0.88 for Minnesota and α = 0.90, 0.88, and 0.90 for Hong Kong.

2.3.4. Individual resilience

Resilience at individual level was measured using the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC10; Connor and Davidson, 2003). Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 ‘never’ to 4 ‘almost always’, with higher scores indicating greater individual resilience. The Chinese version of CD-RISC10 had been validated in a Hong Kong sample (Chow et al., 2018). Scale reliability for the current sample was satisfactory (α = 0.87 for Minnesota and α = 0.92 for Hong Kong).

2.3.5. Family resilience

Resilience at family level was measured using the 32-item short version of the validated Family Resilience Assessment Scale (FRAS-32), which captures three domains of family resilience, namely, (1) family communication and problem solving, (2) maintaining a positive outlook, and (3) utilizing social resources (Li et al., 2016; Sixbey, 2005). Each item was rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 4 ‘strongly agree’, with higher scores indicating greater family resilience. Subscale reliability for the current sample was excellent for family communication and problem solving (α = 0.96 for both regions), satisfactory for maintaining a positive outlook (α = 0.87 for Minnesota and α = 0.86 for Hong Kong), but questionable for the three-item utilizing social resources (α = 0.66 for Minnesota and α = 0.49 for Hong Kong). Therefore, the subscale of utilizing social resources was excluded from subsequent data analyses.

2.4. Data analysis

Datasets from Minnesota and Hong Kong were analyzed separately. Participant demographic characteristics and their pandemic-related stressors were summarized. All instruments were scored per instrument guidelines and summarized using descriptive statistics in SPSS 25.0. Bivariate correlations were examined between study variables. Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between mental health, individual and family resilience, and pandemic-related stressors. All regression models controlled for age, ethnicity, gender, marital status, income level, family caregiving responsibility and number of coresident family members (step 1). Then, additional variables were entered in blocks in each successive step to assess the contributions of pandemic-related stressors (step 2), individual resilience and two domains of family resilience (i.e., family positive outlook, and family communication and problem solving (step 3), and the interaction between individual and family resilience and stressors (step 4) on each mental health outcome. Individual and family resilience variables were only evaluated in the context of interaction terms if they were significant predictors in step 3.

3. Results

Table 1 shows individual and family characteristics, pandemic-related stressors, and mental health outcomes of the Minnesota and Hong Kong sample. Table 2 shows bivariate correlations. Although household size was similar across the Minnesota and Hong Kong samples, more married or cohabitated respondents from Minnesota lived with their spouses and children, while more unmarried respondents from Hong Kong lived with their parents and siblings. The Minnesota sample (M = 2.61, SD = 0.94) had more pandemic-related stressors than Hong Kong sample (M = 1.48, SD = 0.99), with a majority of respondents in Minnesota (90.5%) currently practicing social distancing versus one-third in Hong Kong (36.2%).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables.

| Variable | Minnesota | Hong Kong | Correlations | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| 1. Age | 41.89 (12.86) | 31.6 (12.51) | – | −0.05 | .10* | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.13⁎⁎ | −0.24⁎⁎ | −0.12* | .17⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.20⁎⁎ | −0.20⁎⁎ | −0.27⁎⁎ |

| 2. Femalea | 0.87 (0.34) | 0.72 (0.45) | 0.01 | – | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| 3. White non-Hispanicb | 0.80 (0.40) | – | – | – | – | 0.11* | 0.07 | −0.13⁎⁎ | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.18⁎⁎ | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.05 |

| 4. Married or cohabitatedc | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.31 (0.46) | .70⁎⁎ | 0.02 | – | – | 0.23⁎⁎ | −0.22⁎⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.20⁎⁎ | −0.16⁎⁎ | −0.18⁎⁎ | −0.09 |

| 5. Above 75th percentile household incomed | 0.49 (0.50) | 0.15 (0.36) | .18⁎⁎ | 0.01 | – | 0.20⁎⁎ | – | −0.24⁎⁎ | 0.12* | −0.10* | 0.11* | 0.03 | .10* | 0.10* | 0.07 | −0.15⁎⁎ | −0.15⁎⁎ | −0.08 |

| 6. Below poverty line household incomed | 0.05 (0.23) | 0.15 (0.35) | −0.08 | 0.10* | – | −0.16⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎⁎ | – | 0.03 | 0.15⁎⁎ | 0.12* | 0.05 | −0.09* | −0.12* | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 7. Caregiver for children/grandchildrend | 0.53 (0.50) | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.09* | – | 0.51⁎⁎ | 0.12⁎⁎ | 0.02 | – | −0.13⁎⁎ | 0.41⁎⁎ | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.05 | 0.08 |

| 8. Caregiver for adult family membersd | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.14⁎⁎ | 0.03 | – | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.08* | 0.09* | – | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.03 |

| 9. Number of co-resident family members | 3.54 (1.48) | 3.56 (1.16) | −0.05 | 0.05 | – | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.13⁎⁎ | – | .12* | −0.01 | −0.09 | −0.17⁎⁎ | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.00 |

| 10. Pandemic-related stressorse | 2.61 (0.94) | 1.48 (0.99) | −0.01 | 0.04 | – | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.15⁎⁎ | – | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.11* | 0.11* | 0.10* |

| 11. Individual resilience | 26.71 (5.83) | 22.66 (6.31) | 0.11⁎⁎ | −0.11* | – | 0.06 | 0.09* | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.03 | – | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.39⁎⁎ | −0.32⁎⁎ | −0.20⁎⁎ | −0.23⁎⁎ |

| 12. Maintaining a family-level positive outlook | 19.45 (2.65) | 17.61 (3.64) | 0.05 | 0.03 | – | 0.08 | 0.08* | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | .36⁎⁎ | – | 0.79⁎⁎ | −0.20⁎⁎ | −0.11* | −0.13⁎⁎ |

| 13. Family communication and problem solving | 71.18 (10.58) | 64.28 (10.89) | 0.16⁎⁎ | 0.06 | – | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.06 | −0.00 | 0.15⁎⁎ | −0.08* | −0.06 | −0.03 | .33⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | – | −0.26⁎⁎ | −0.14⁎⁎ | −0.20⁎⁎ |

| 14. Depression symptoms | 6.58 (4.89) | 5.07 (4.59) | −0.19⁎⁎ | −0.01 | – | −0.13⁎⁎ | −0.13⁎⁎ | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.15⁎⁎ | −0.43⁎⁎ | −0.28⁎⁎ | −0.29⁎⁎ | – | 0.63⁎⁎ | 0.79⁎⁎ |

| 15. Anxiety symptoms | 3.30 (3.87) | 3.70 (4.21) | −0.14⁎⁎ | 0.03 | – | −0.10* | −0.10* | 0.09* | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.12⁎⁎ | −0.33⁎⁎ | −0.23⁎⁎ | −0.22⁎⁎ | 0.83⁎⁎ | – | 0.69⁎⁎ |

| 16. Stress level | 7.73 (5.04) | 5.79 (4.86) | −0.16⁎⁎ | 0.04 | – | −0.11⁎⁎ | −0.10* | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.14⁎⁎ | −0.39⁎⁎ | −0.23⁎⁎ | −0.24⁎⁎ | 0.88⁎⁎ | 0.84⁎⁎ | – |

Note. The results for the Minnesota sample (n = 442) are shown above the diagonal. The results for the Hong Kong sample (n = 597) are shown below the diagonal.

0 = male, 1 = female.

0 = non-White, 1 = White non-Hispanic.

0 = single, divorced/separated, widowed, 1 = married or cohabitated.

0 = no, 1 = yes.

pandemic-related stressors (yes/no): currently practicing social distancing or quarantining, family members inside/outside the home experiencing or suspected of having symptoms of COVID, family members inside the home working in healthcare or other high risk jobs for contracting COVID-19, family members working from home in response to COVID-19, and family members experiencing reduced employment.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

3.1. Minnesota findings

In Minnesota, nearly two-thirds of respondents (60.4%) showed elevated symptoms of depression, ranging from mild to extremely severe, while over one-third (34.6%) showed elevated symptoms of anxiety, ranging from mild to extremely severe. Furthermore, over three-quarters of respondents (77.4%) reported elevated stress symptoms, ranging from mild to extremely severe.

Table 3a presents the results of three hierarchical regression analyses for depression, anxiety, and stress outcomes in Minnesota, respectively. For the main effect models in step 3, older age (p < 0.001) and living with more family members (p < 0.05) were positively associated with each of the mental health outcomes. Married or cohabitating status (β = −0.12, p = 0.022) was associated with lower symptoms of anxiety relative to being unmarried, while caregiving responsibility for children or grandchildren (β = 0.13, p = 0.010) was associated with higher stress symptoms. Pandemic-related stressors significantly predicted depression (β = 0.11, p = 0.016), anxiety (β = 0.11, p = 0.023) and stress symptoms (β = 0.09, p = 0.042). Individual and family resilience was negatively associated with the mental health. Specifically, greater individual resilience predicted lower symptoms of depression (β = −0.25, p < 0.001), anxiety (β = −0.14, p = 0.008) and stress (β = −0.16, p = 0.002). When looking at family resilience subscales, family communication and problem solving, but not positive family outlook, was a significant predictor of mental health. Higher levels of family communication and problem solving predicted lower symptoms of depression (β = −0.23, p = 0.002) and stress (β = −0.24, p = 0.002).

Table 3a.

Multiple Regressions Predicting Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Outcomes in Minnesota (n = 442).

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | ||||||||||

| Predictors | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 |

| Age | −0.21⁎⁎ | −0.20⁎⁎ | −0.16⁎⁎ | −0.16⁎⁎ | −0.20⁎⁎ | −0.19⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎⁎ | −0.28⁎⁎ | −0.27⁎⁎ | −0.24⁎⁎ | −0.24⁎⁎ |

| Femalea | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| White non-Hispanicb | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08+ | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Married or cohabitatedc | −0.09+ | −0.09+ | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.13* | −0.13* | −0.12* | −0.12* | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.04 |

| Above 75th percentile household incomed | −0.08+ | −0.09+ | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.08+ | −0.09+ | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.05 |

| Below poverty line household incomed | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| Caregiver for children/grandchildrend | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13* | 0.14⁎⁎ |

| Caregiver for adult family membersd | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Number of co-resident family members | −0.11* | −0.12* | −0.14* | −0.14* | −0.15⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎⁎ | −0.18⁎⁎ | −0.11* | −0.12* | −0.14⁎⁎ | −0.14⁎⁎ |

| Pandemic-related stressorse | 0.10* | 0.11⁎⁎ | 0.11⁎⁎ | 0.10* | 0.11* | 0.11* | 0.09* | 0.09* | 0.09* | |||

| Individual resilience - mean center | −0.25⁎⁎ | 0.08⁎⁎ | −0.14⁎⁎ | 0.13 | −0.16⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎⁎ | ||||||

| Maintaining a family-level positive outlook - mean center | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.14+ | 0.15+ | ||||||

| Family communication and problem solving (FCPS) - mean center | −0.23⁎⁎ | −0.21⁎⁎ | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.24⁎⁎ | 0.03 | ||||||

| Pandemic-related stressors x Individual resilience | −0.34⁎⁎ | −0.28+ | – | |||||||||

| Pandemic-related stressors x FCPS | – | – | −0.28* | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

0 = male, 1 = female.

0 = non-White, 1 = White non-Hispanic.

0 = single, divorced/separated, widowed, 1 = married or cohabitated.

0 = no, 1 = yes.

pandemic-related stressors (yes/no): currently practicing social distancing or quarantining, family members inside/outside the home experiencing or suspected of having symptoms of COVID, family members inside the home working in healthcare or other high risk jobs for contracting COVID-19, family members working from home in response to COVID-19, and family members experiencing reduced employment.

p<0.10.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

Moreover, significant two-way interaction effects between resilience and pandemic-related stressors emerged for depression and stress symptoms in step 4. Individual resilience significantly moderated the relationship between pandemic-related stressors and depression, F(1, 427) = 5.43, p = 0.020. Specifically, the negative association between pandemic-related stressors and depression was tempered with increasing level of individual resilience (see Fig. 1 a). Simple slope analyses revealed that the association between pandemic-related stressors and depression was significant when individual resilience was low, t = 3.35, p = 0.001. However, when individual resilience was high, the association between pandemic-related stressors and depression became insignificant, t = −0.02, p = 0.987. Further, family communication and problem solving significantly moderated the association between pandemic-related stressors and depression, F(1, 427) = 4.62, p = 0.032. Specifically, the negative association between pandemic-related stressors and depression was tempered with increasing levels of family communication and problem solving (see Fig. 1 b). Simple slope analyses revealed that the association between pandemic-related stressors and depression was significant when family communication and problem solving was low, t = 3.02, p = 0.003. When family communication and problem solving was high, the association between pandemic-related stressors and depression became insignificant, t = −0.18, p = 0.854.

Fig. 1.

Pandemic-related stressors predicting (a) depression severity by individual resilience; or (b) stress severity by family communication and problem solving in Minnesota

Note.. Pandemic-related stressors (yes/no): currently practicing social distancing or quarantining, family members inside/outside the home experiencing or suspected of having symptoms of COVID, family members inside the home working in healthcare or other high risk jobs for contracting COVID-19, family members working from home in response to COVID-19, and family members experiencing reduced employment.

3.2. Hong Kong findings

In Hong Kong, nearly half of respondents (45.4%) showed elevated levels of depression, ranging from mild to extremely severe elevations, while over one-third (38.0%) reported elevated symptoms of anxiety, also ranging from mild to extremely severe. Furthermore, nearly two-thirds of respondents (61.6%) showed elevated stress symptoms, ranging from mild to extremely severe.

Table 3b shows the results of the hierarchical regression analyses for the Hong Kong sample. For the main effect models in step 3, older age (p < 0.01) was associated with three positive mental health. Caregiving responsibility for children or grandchildren (β = 0.13, p = 0.005) was associated with higher stress symptoms; while caregiving for adult family members (i.e., older parents or spouses) was associated with higher symptoms of depression (β = 0.08, p = 0.043) and stress (β = 0.09, p = 0.021). Pandemic-related stressors significantly predicted depression (β = 0.15, p < 0.001), anxiety (β = 0.12, p < 0.001) and stress symptoms (β = 0.15, p < 0.001). Individual resilience and family resilience was negatively associated with the mental health. Specifically, greater individual resilience predicted lower symptoms of depression (β = −0.34, p < 0.001), anxiety (β = −0.26, p = 0.002) and stress (β = −0.33, p < 0.001). When looking at family resilience subscales, family-level positive outlook and family communication and problem solving were significant predictors of positive mental health. Higher levels of family-level positive outlook predicted lower symptoms of depression (β = −0.09, p = 0.036) and anxiety (β = −0.10, p = 0.036), whereas a higher level of family communication and problem solving predicted lower symptoms of depression (β = −0.10, p = 0.018).

Table 3b.

Multiple Regressions Predicting Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Outcomes in Hong Kong (n = 597).

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | ||||||||||

| Predictors | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 |

| Age | −0.21⁎⁎ | −0.21⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎⁎ | −0.16⁎⁎ | −0.15* | −0.15* | −0.12* | −0.11* | −0.18⁎⁎ | −0.18⁎⁎ | −0.14⁎⁎ | −0.13* |

| Femalea | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Married or cohabitatedb | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.03 |

| Above 75th percentile household incomec | −0.10* | −0.11* | −0.07+ | −0.07+ | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.07+ | −0.08+ | −0.05 | −0.05 |

| Below poverty line household incomec | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.08+ | 0.08* | 0.09* | 0.09* | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Caregiver for children/grandchildrenc | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.09+ | 0.11* | 0.13⁎⁎ | 0.13⁎⁎ |

| Caregiver for adult family membersc | 0.09* | 0.08* | 0.08* | 0.08* | 0.08+ | 0.07+ | 0.07+ | 0.07+ | 0.10* | 0.09* | 0.09* | 0.09* |

| Number of co-resident family members | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.08+ | −0.08+ |

| Pandemic-related stressorsd | 0.15⁎⁎ | 0.14⁎⁎ | 0.15⁎⁎ | 0.12⁎⁎ | 0.12⁎⁎ | 0.13⁎⁎ | 0.15* | 0.15⁎⁎ | 0.15⁎⁎ | |||

| Individual resilience - mean center | −0.34⁎⁎ | −0.34⁎⁎ | −0.26⁎⁎ | −0.26⁎⁎ | −0.33⁎⁎ | −0.33⁎⁎ | ||||||

| Maintaining a family-level positive outlook (MPFO) - mean center | −0.09* | −0.14+ | −0.10* | −0.22* | −0.07 | −0.17* | ||||||

| Family communication and problem solving - mean center | −0.10* | −0.10* | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.08+ | −0.07 | ||||||

| Pandemic-related stressors x MPFO | 0.06 | 0.14* | 0.12+ | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | .04 | .06 | .25 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

0 = male, 1 = female.

0 = single, divorced/separated, widowed, 1 = married or cohabitated.

0 = no, 1 = yes.

pandemic-related stressors (yes/no): currently practicing social distancing or quarantining, family members inside/outside the home experiencing or suspected of having symptoms of COVID, family members inside the home working in healthcare or other high risk jobs for contracting COVID-19, family members working from home in response to COVID-19, and family members experiencing reduced employment.

+p<0.10.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

Moreover, for the interaction models in step 4, family positive outlook significantly moderated the association between pandemic-related stressors and anxiety symptoms in Hong Kong, F(1, 583) = 3.88, p = 0.049. Interestingly, the negative association between pandemic-related stressors and anxiety was magnified with higher family-level of positive outlook (see Fig. 2 ). Simple slope analyses revealed that the association between pandemic-related stressors and anxiety was significant when family-level positive outlook was high, t = 3.58, p < 0.001. When family-level positive outlook was low, the association between pandemic-related stressors and anxiety became insignificant, t = 1.23, p = 0.218.

Fig. 2.

Pandemic-related stressors predicting anxiety severity by family positive outlook in Hong Kong

Note.. Pandemic-related stressors (yes/no): currently practicing social distancing or quarantining, family members inside/outside the home experiencing or suspected of having symptoms of COVID, family members inside the home working in healthcare or other high risk jobs for contracting COVID-19, family members working from home in response to COVID-19, and family members experiencing reduced employment.

4. Discussion

Drawing upon Ecological Framework and the Family Adjustment and Adaptation Response Model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; McCubbin & Patterson, 1983), our study is one of the first to examine how individual adjustment is influenced by not only individual characteristics associated with resilience but also the embedded family and sociocultural context. Our findings were generally supportive of our hypotheses. In both Minnesota and Hong Kong, pandemic-related stressors were associated with more mental health symptoms (H1). Individuals who experienced more stressors from the pandemic not surprisingly also reported more depression, anxiety, and stress. Irrespective of the extent of pandemic-related stressors experienced by individuals, higher levels of individual resilience were associated with fewer mental health symptoms in both regions (H2). When looking at family-level resilience, different elements of family functioning were relevant to successful coping in each region. Strong family communication and problem solving predicted fewer symptoms of depression and stress in Minnesota, while high positive family outlook predicted fewer depression and anxiety symptoms in Hong Kong (H3). As predicted, in Minnesota, a high level of individual resilience buffered the relationship between pandemic-related stressors and depression symptoms (H4). Interestingly, different components of family resilience moderated the association between pandemic-related stressors on stress symptoms in Minnesota and Hong Kong (H5). A high level of family communication and problem solving skills buffered the association between pandemic-related stressors and stress symptoms in Minnesota. Individuals in families with stronger communication and problem solving skills seemed to experience less stress associated with negative pandemic events, such as job loss or illness, relative to individuals in families with weaker communication and problem solving. Contrary to our expectations, a high level of family positive outlook was associated with a stronger relationship between pandemic-related stressors and anxiety in Hong Kong. In this region, individuals in families who tended to maintain a strong positive outlook who were also confronted with more stressors related to the pandemic tended to experience more anxiety than individuals in families with less of a positive outlook. Together, our findings highlight unique sources of strength and resilience for individuals in each region when coping with the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Minnesota, the role of individual resilience as a protective psychological resource to individuals’ mental health was aligned with other pandemic studies conducted in individualistic or independently-oriented cultures, such as Norway and the U.S. nationally (Havnen et al., 2020; Rihem et al., 2021). Our findings demonstrated that in a more individualistic culture that stresses self-autonomy, individual resilience was associated with less depression in the face of COVID-19 related stressors. These cultures may benefit from universal interventions designed foster individual resilience during a pandemic.

As posited by the FAAR model (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983), even in a more individualistic culture, family communication and problem solving (i.e., family resources) can moderate how individuals experience stressors. Particularly when many pandemic stressors are family related or impact the whole family (i.e., illness of family members, job loss, etc.), strong family functioning is critical to the successful coping with these challenges. Our findings highlight that even in individualistic societies, family still plays a significant role. Particularly when facing a pandemic situation and stay-at-home orders, open family communication and collaborative problem-solving are protective of family members’ mental health.

In Hong Kong, high levels of family-based positive outlook surprisingly were associated with an exacerbation of the adverse relationship between pandemic-related stressors and anxiety symptoms. While this finding is counterintuitive, we speculate that this may be explained by the Chinese stress and coping pattern known as fatalistic voluntarism. Fatalistic voluntarism is described as the combination of an acceptance of present adversities and an exertion of personal efforts to change the situation, with hope and confidence for a better future (Lee, 1995 as cited by Chui and Chan, 2007). At lower levels of pandemic-related stressors, believing that the family can cope with the present challenges of the pandemic is beneficial to individuals’ psychological adjustment. However, there is a mismatch between expectations and reality when facing high level of pandemic-related stressors in closely-connected families. An overly positive outlook could create cognitive dissonance with the reality of the challenges facing a family. It may be that the protective effects of having a family-based positive outlook vary as exposure to pandemic-related stressors increases. Additional research will be important to further elucidate the complex relationship between family-level optimism and coping with varying levels of stress.

While not specific research questions, several other findings emerged supporting existing research on coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consistent with existing pandemic research (Cooke et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020), a high proportion of adults in Minnesota and Hong Kong had elevated levels of depression, anxiety and stress symptoms. Our findings also elucidated an association between caregivers’ roles and mental health outcomes in both Minnesota and Hong Kong. Other research has supported the impact of a caregiving role on mental health during the pandemic, also noting the increased stress associated with caregiving responsibilities may negatively impact family relationships (Russell et al., 2020). Although older adults are more vulnerable to the COVID-19, our findings were also consistent with previous studies demonstrating that older adults had better mental health than younger adults in both regions (e.g., Havnen et al., 2020; Lau et al., 2020; Öcal et al., 2020). We found that older adults, aged 60 or above, in Minnesota experienced relatively few pandemic-related stressors when compared to younger adults. For example, older adults in Minnesota are more likely to be retired and may have found it less intrusive to stay at home in accordance with social distancing recommendations. Furthermore, older adults in both Minnesota and Hong Kong reported higher levels of individual resilience, relative to young adults, also supporting their ability to cope with pandemic-related stressors.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that attempts to compare different types of resilience and they may associate with variable coping with pandemic-related stressors across Eastern and Western cultures. We need to be aware of the unique cultural context and pandemic experiences of each region. For most Minnesotans, this was their first experience with a pandemic and many of the recommended public health measures (e.g., social distancing, mask wearing) were newly encountered and viewed by some as governmental intrusion or overreach (Fairchild et al., 2020). Hong Kong has previously experienced a SARS epidemic, making public health strategies more familiar and perhaps faced with less resistance (Lau et al., 2020). Both regions also experienced social unrest during the study period, and we acknowledge that it is hard to disentangle the psychological distress simultaneously triggered by the mass protests and the pandemic.

Several study limitations are important to note when interpreting our results. First, our study used a cross-sectional design and thus we cannot assume causal relationships among our key study variables. A longitudinal study design will be useful to better elucidate the adjustment and adaptation processes of individuals and families across cultures. Second, our data were collected via an online survey and relied exclusively on self-report. This may increase the chance of common method variance among constructs as well as biases in responding. Future studies could consider examining the effect of family resilience by recruiting multiple family members from a single family system. Third, convenience sampling and bias toward female participant limits the generalizability of our findings. Regardless, our results are strengthened by the administration of widely used and validated measures of mental distress, individual resilience and family resilience.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global phenomenon impacting individual and family adjustments across cultures and contexts. Regardless of individualistic or collectivistic cultural orientation, individual resilience and family resilience are protective factors in supporting global mental health. We call for universal interventions strengthening individual coping and resilience when facing pandemic-type stressors. This type of intervention may help reduce negative impacts on mental health and support the ability to rebound successfully post-pandemic. Our results also highlight the importance of careful consideration of family and cultural context when considering how to support mental health during a pandemic. It is equally important to adapt culturally-specific interventions targeting different elements of family resilience. Families from the West may be more likely to privilege clarity with family communication and collaborative problem solving, while the East may be comfortable with uncertainty and the unknown with a positive family outlook (Lee, 2020). Furthermore, it is essential to provide additional psychosocial support to vulnerable populations, such as family caregivers.

5. Conclusion

Our study is the first to examine and compare the role of individual and family resilience in moderating the relationships between pandemic-related stressors and depression, anxiety, and stress in two culturally distinct regions. Our findings highlight the role of cultural context in coping with a global pandemic. Across two distinct cultures, aspects of individual and family functioning related to individuals’ successful coping and supported mental health. The similarities as well as unique sources of resilience in each region are suggestive of universal as well as culturally-specific intervention targets. Through supporting processes most likely to support coping within each culture, interventions may most effectively ameliorate the negative impacts of a global pandemic and promote mental health.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Athena C.Y. Chan: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Timothy F. Piehler: Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Grace W.K. Ho: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Department-sponsored grant award in support of global COVID-19 pandemic research, Department of Family Social Science, University of Minnesota

Acknowledgements

None.

Reference

- Amerio A., Bianchi D., Santi F., Costantini L., Odone A., Signorelli C., Costanza A., Serafini G., Amore M., Aguglia A. Covid-19 pandemic impact on mental health: a web-based cross-sectional survey on a sample of Italian general practitioners. Acta bio-medica: Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91(2):83–88. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G.A., Ho S.M.Y., Chan J.C.K., Kwong R.S.Y., Cheung C.K.Y., Wong C.P.Y., Wong V.C.W. Psychological resilience and dysfunction among hospitalized survivors of the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: A latent class approach. Health Psychology. 2008;27(5):659–667. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Harvard University Press; 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.K.W., Wong C.W., Tsang J., Wong K.C. Psychological distress and negative appraisals in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Psychol Med. 2004;34(7):1187–1195. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704002272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow K.M., Tang W.K.F., Chan W.H.C., Sit W.H.J., Choi K.C., Chan S. Resilience and well-being of university nursing students in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1119-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui W.Y.-Y., Chan S.W.-C. Stress and coping of Hong Kong Chinese family members during a critical illness. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(2):372–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor K.M., Davidson J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J., Madhavan S., Mokashi M., Amanuel H., Johnson N.R., Pace L.E., Bartz D. Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the Covid-19 pandemic: A review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke J.E., Eirich R., Racine N., Madigan S. Prevalence of posttraumatic and general psychological stress during COVID-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild A., Gostin L., Bayer R. Vexing, Veiled, and Inequitable: social Distancing and the “Rights” Divide in the Age of COVID-19. The American Journal of Bioethics. 2020;20(7):55–61. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1764142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner W.L., Gabriel S., Lee A.Y. I” value freedom, but “We” value relationships: Self-construal priming mirrors cultural differences in judgment. Psychol Sci. 1999;10(4):321–326. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Havnen A., Anyan F., Hjemdal O., Solem S., Gurigard Riksfjord M., Hagen K. Resilience moderates negative outcome from stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated-mediation approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6461. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G., Hofstede G.J., Minkov M. Revised and Expanded 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2010. Cultures and organizations: Software of the Mind. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department . 2020. Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics.https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B10100022020MM10B0100.pdf October 2020 [Data file]. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Hou W.K., Tong H., Liang L., Li T.W., Liu H., Ben-Ezra M., Goodwin R., Lee T.M.-C. Probable anxiety and components of psychological resilience amid COVID-19: A population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun E.-.M. Adjustment of single parent family-the buffering effect of family resilience. Journal of Korean Home Management Association. 2007;25(5):107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Sherman D.K., Taylor S.E. Culture and social support. American Psychologist. 2008;63(6):518–526. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau B.H.P., Chan C.L.W., Ng S.-.M. Resilience of Hong Kong people in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from a survey at the peak of the pandemic in Spring 2020. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/02185385.2020.1778516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R.P.L. In: Chinese Societies and Mental Health. Lin T.Y., Tseng W.S., Yeh E.K., editors. Oxford University Press; Hong Kong: 1995. Cultural tradition and stress management in modern society: learning from the Hong Kong experience; pp. 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.-.Y. The musings of a family therapist in Asia when COVID-19 struck. Fam Process. 2020;59(3):1018–1023. doi: 10.1111/famp.12577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhao Y., Zhang J., Lou F., Cao F. Psychometric properties of the shortened Chinese version of the Family Resilience Assessment Scale. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(9):2710–2717. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0432-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond P.F., Lovibond S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond S.H., Lovibond P.F. Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1996. Manual For the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. [Google Scholar]

- Lutha S.S., Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000;12(4):857–885. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H.R., Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98(2):224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin H.I., Patterson J.M. The family stress process: The double ABCX model of adjustment and adaptation. Marriage & family review. 1983;6(1–2):7–37. doi: 10.1300/J002v06n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa M.T., Lovibond P.F., Laube R. Psychometric properties of a Chinese version of the 21-item depression anxiety stress scales (DASS21) Sydney, NSW: Transcultural Mental Health Centre. Cumberland Hospital. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Öcal A., Cvetković V.M., Baytiyeh H., Tedim F.M.S., Zečević M. Public reactions to the disaster COVID-19: a comparative study in Italy, Lebanon, Portugal, and Serbia. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk. 2020;11(1):1864–1885. doi: 10.1080/19475705.2020.1811405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prime H., Wade M., Browne D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist. 2020 doi: 10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehm K.E., Brenneke S.G., Adams L.B., Gilan D., Lieb K., Kunzler A.M., Smail E.J., Holingue C., Stuart E.A., Kalb L.G., Thrul J. Association between psychological resilience and changes in mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell B.S., Hutchison M., Tambling R., Tomkunas A.J., Horton A.L. Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent–child relationship. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2020;51(5):671–682. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01037-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sixbey M.T. University of Florida; Florida, United States: 2005. Development of the Family Resilience Assessment Scale to Identify Family Resilience Constructs. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Taouk M.T., Lovibond P.F., Laube R. Psychometric properties of a Chinese version of the short Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS21) Report for New South Wales Transcultural Mental Health Centre, Cumberland Hospital, Sydney. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau (2019). Quick Facts: Minnesota, United States [Data file]. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/MN,US/PST045219.

- Walsh F. The concept of family resilience: Crisis and challenge. Fam Process. 1996;35(3):261–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2016. Strengthening Family Resilience. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. Loss and resilience in the time of COVID-19: Meaning making, hope, and transcendence. Fam Process. 2020;59(3):898–911. doi: 10.1111/famp.12588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020, 7 May 2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: Information for the public.

- Wu T., Jia X., Shi H., Niu J., Yin X., Xie J., Wang X. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Phan L., Chen-Li D., Iacobucci M., Ho R., Majeed A., McIntyre R.S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]