Abstract

Purpose

To explore how endophthahnitis presented from 2009 to 2019 in a West Virginia population particularly affected by the national opioid crisis. The analysis explores the relationship between the type of endophthahnitis and mortality, accounting for factors including age, gender, type of organism, and intravenous drug use (IVDU).

Methods

The electronic health record of West Virginia University (WVU) Medicine was queried for all patients managed for endophthalmitis from October 2009 to October 2019. For each of the included subjects, age, gender, history of IVDU, culture results, concomitant endocarditis, type of endophthalmitis, and the date of diagnosis were extracted. Mortality data were obtained from WVU’s electronic medical record, the Social Security Death Index, and public obituaries. Mortality results were represented by a Kaplan–Meier Survival curve following each patient for one year from the date of diagnosis. Results were analyzed using unadjusted and adjusted Cox Proportional Hazard models.

Results

One-year mortality was 14 out of 113 endogenous cases (12.4%) compared to 6 out of 173 exogenous cases (3.5%). Endogenous endophthalmitis cases had significantly higher mortality than exogenous ones within one year of diagnosis (p = 0.0034). The unadjusted Cox proportional hazards model revealed that the type of endophthalmitis (endogenous vs. exogenous) was the only variable with a significant impact on 1-year mortality with a hazard ratio of 3.78 (p = 0.01). However, the hazard ratio for endogenous infections rose to 10.91 (Cl 3.544–33.595) when the other variables of age, gender, organism, and IVDU were controlled (p < 0.01). The Cox proportional hazard ratios for age group, gender, organism type, and history of IVDU were not significantly different when adjusted for all other variables.

Conclusion

Endogenous cases, which were significantly overrepresented in West Virginia, were associated with a significantly higher 1-year mortality rate than the exogenous ones. Age, gender, organism type, and history of IVDU have less, if any, modifying effect on mortality.

Keywords: Endogenous endophthalmilis, Exogenous endophthalmilis, Drug use-related endophthalmilis

Introduction

Endophthalmitis can be classified as either endogenous or exogenous. Endogenous cases involve the hematogenous spread of microbes to the eye, while exogenous cases are caused by direct invasion of the globe from various insults including surgery, trauma, and keratitis [1], Regardless of the subtype, visual outcomes of endophthalmilis are poor, and some evidence suggests that visual outcomes have not significantly improved in five decades [2, 3], Endophthalmitis is one of few ophthalmologic pathologies with a significant mortality rate, although certain subtypes (i.e., post-cataract) have not consistently been associated with mortality [2,4], Endophthalmilis may present as an acute, subacute or chronic infection. Bacterial cases are commonly acute or subacute, while fungal cases are frequently subacute or chronic. Presenting signs vary from mild to severe infraocular inflammation. Untreated endophthalmitis may progress to panophthalmitis and orbital cellulitis requiring enucleation.

Endogenous endophthalmilis is associated with higher fatality rates than exogenous infections, with mortality rates approximating 4% [5–7], Intravenous drug use (IVDU) is considered a prime risk factor for the development of endogenous endophthalmitis, along with diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and malignancy [8, 9], While fungi are typically associated with IVDU-associated endogenous endophthalmilis, a significant proportion of these cases may be caused by staphylococcus, streptococcus, klebsiella, and other bacteria [4, 9–11]. Endogenous endophthalmilis preferentially affects the right eye, presumably due to direct branching of the common carotid artery from the aortic arch.

IVDU has increased over the past decade, with a concomitant fourfold rise in the incidence of drug use-related endogenous endophthalmilis [12], In every year since at least the 2010 census, West Virginia had the highest rate of death due to drug overdose and one of the highest rates of IVDU [13]. According to the Centers for Disease Control, West Virginia experienced 57.8 deaths per 100,000 due to drug overdose in 2017. Ohio (ranked second) experienced 46.3 of these deaths per 100,000. This study seeks to explore how endophthalmitis has presented from 2009 to 2019 in this West Virginia population that is particularly affected by the national opioid crisis. A subsequent analysis explores the relationship between the type of endophthalmitis and mortality, accounting for factors including age, gender, type of organism, and history of IVDU.

Materials and methods

Data source and study population

West Virginia University (WVU) Medicine is the largest healthcare provider in the State of West Virginia, with facilities in 41 of the state’s 55 counties and additional clinics in Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland [14], WVU’s electronic health record (EHR) was queried for all patients who were managed for endophthalmitis from October 2009 to October 2019. ICD codes included ICD-9 codes (360.0/360.1/379.63) and ICD-10 codes (H44.0/H44.1/H59.43). Patients were included if they received a diagnosis before October 2009 but continued management of endophthalmitis with WVU from October 2009 to October 2019. The WVU Institutional Review Board granted this study exempt status and all data do not include patient identifiers. This study was conducted in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki and United States federal and State laws.

For each of the included subjects, age, gender, history of IVDU, culture results, concomitant endocarditis, type of endophthalmitis, and diagnosis date were extracted. If a subject ever reported a history of IVDU, even if he/she later denied it, the subject was included as having a history of IVDU. Infections were considered “culture-negative” if all cultures (ocular and non-ocular) failed to demonstrate any causative organisms. All infections deemed “bacterial” exhibited growth of at least one bacterial species on ocular or non-ocular cultures. Similarly, infections were classified as “fungal” based on fungal growth from ocular or non-ocular cultures. Infections were considered exogenous if the subject had recent trauma, keratitis, or ocular procedures. Infections were considered endogenous if the patients had a concurrent infection in their blood or other idenlifiable sources, such as pneumonia, endocarditis, cholangitis, pyelonephritis, osteomyelitis, or skin abscesses. The culture data were unobtainable in seven cases; these were excluded when analyzing the spectrum of microorganisms.

Mortality data were extracted from WVU’s EHR in combination with the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) and public obituaries. If a patient’s death was recorded in WVU’s EHR, this death date was used for analysis. For patients with no known death in the EHR, the SSDI was queried. The SSDI is a database of death records created from the US Social Security Administration’s Death Master File Extract and includes the death of any person who had a Social Security Number and whose death was reported to the Social Security Administration (SSA). To capture those deaths that may not have yet been reported to the SSA, public obituaries were subsequently searched for potentially unrecorded deaths.

Statistical analysis

Mortality results were represented by a Kaplan–Meier Survival curve following each patient for one year from diagnosis date. Results were analyzed using unadjusted and adjusted Cox Proportional Hazard models. All p values were nominal and a value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

Demographics and baseline characteristics

Table 1 displays the demographics and baseline characteristics of the 286 subjects managed for endophthalmitis at WVU from October 2009 to October 2019. The majority of these cases (173) were exogenous, compared to 113 cases of endogenous endophthalmitis. The mean age was significantly younger in the endogenous population (43.7 years, SD = 17.4) compared to the exogenous population (65.0 years, SD = 17.6) (p < 0.001). Seventy-two of the 113 endogenous patients were male (63.7%), while 86 of the 173 exogenous patients were male (49.7%) (p < 0.027). 63.7% of endogenous cases (72 out of 113) involved patients with a history of IV drug use, compared to 1.2% of exogenous cases (2 out of 173) (p < 0.001). Across both types of endophthalmitis, 20.3% of females were IV drug users compared to 30.4% of males who were IV drug users. Furthermore, 15.9% of endogenous cases (18 out of 113) had concomitant endocarditis, while just 0.6% of exogenous cases (1 out of 173) had the condition (p < 0.001). The earliest diagnosis date was in 2004 for patients managed for endophthalmitis between 2009 and 2019. The incidence of endophthalmitis increased over this decade, with eight patients diagnosed in 2009 and 43 patients diagnosed in 2018 (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Baseline Characteristics. First p value tests the hypothesis that subjects were evenly distributed in all possible subgroups. Second p value tests the hypothesis that endogenous and exogenous populations are the same

| Total | p | Endogenous | Exogenous | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 286 | 113 | 173 | ||

| Age (median, mean (SD)) | 60.5, 56.6 (20.4) | 39, 43.69 (17.44) | 68, 64.95 (17.59) | <0.001 | |

| Age group (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| 10–20 | 7 (2.5) | 2 (1.8) | 5 (2.9) | ||

| 20–40 | 64 (22.4) | 55 (48.7) | 9 (5.2) | ||

| 40–60 | 72 (25.2) | 36 (31.9) | 36 (20.8) | ||

| 60–80 | 108 (37.8) | 17 (15.0) | 91 (52.6) | ||

| 80–100 | 35 (12.2) | 3 (2.7) | 32 (18.5) | ||

| Gender = M (%) | 158 (55.2) | 0.0761 | 72 (63.7) | 86 (49.7) | 0.027 |

| Year of diagnosis (%) | <0.001 | 0.477 | |||

| 2004 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 2008 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| 2009 | 8 (2.8) | 2 (1.8) | 6 (3.5) | ||

| 2010 | 14 (4.9) | 2 (1.8) | 12 (6.9) | ||

| 2011 | 11 (3.9) | 4 (3.6) | 7 (4.0) | ||

| 2012 | 27 (9.5) | 12 (10.7) | 15 (8.7) | ||

| 2013 | 27 (9.5) | 8 (7.1) | 19 (11.0) | ||

| 2014 | 31 (10.9) | 15 (13.4) | 16 (9.2) | ||

| 2015 | 26 (9.1) | 12 (10.7) | 14 (8.1) | ||

| 2016 | 34 (11.9) | 15 (13.4) | 19 (11.0) | ||

| 2017 | 36 (12.6) | 13 (11.6) | 23 (13.3) | ||

| 2018 | 43 (15.1) | 15 (13.4) | 28 (16.2) | ||

| 2019 | 26 (9.1) | 13 (11.6) | 13 (7.5) | ||

| History of IVDU (%) | 74 (25.9) | <0.001 | 72 (63.7) | 2 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Endocarditis (%) | 19 (6.6) | <0.001 | 18 (15.9) | 1 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Organism type (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Bacterial | 141 (50.9) | 48 (43.2) | 93 (56.0) | ||

| Mixed (bacterial and fungal) | 6 (2.2) | 3 (2.7) | 3 (1.8) | ||

| Fungal | 22 (7.9) | 19 (17.1) | 3 (1.8) | ||

| Culture-negative | 108 (39.0) | 41 (36.9) | 67 (40.4) |

Fig. 1.

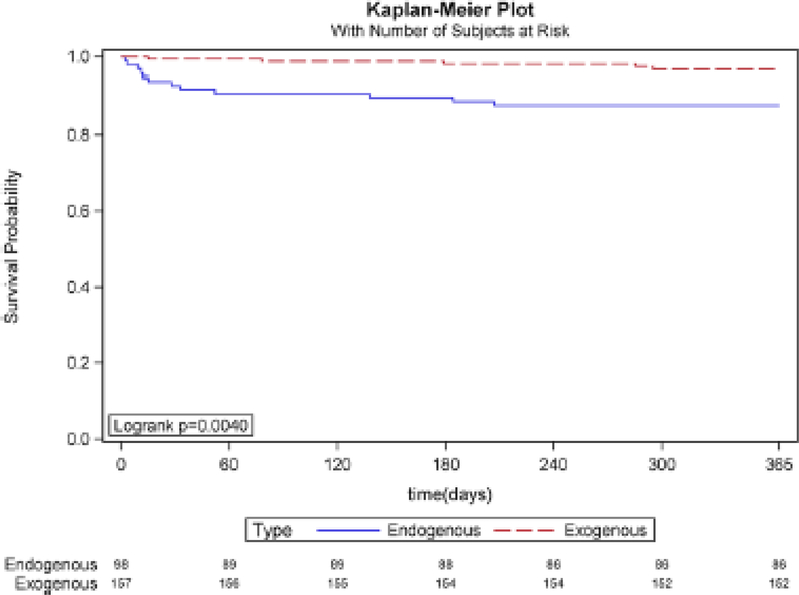

Kaplan–Meier plot of 1-year mortality associated with endophthalmitis. The 1-year mortality was significantly higher in the endogenous group (12.2%) than the exogenous group (3.2%) (p = 0.0040)

The most common etiology of exogenous endophthalmitis was postoperative infection (Table 2). Fifty-two cases occurred after cataract surgery, which was the most common surgery associated with exogenous endophthalmitis. This was followed by bleb-related (18 cases), post-penetrating keratoplasty (11 cases), post-pars plana vitrectomy (10 cases), and glaucoma drainage device-related infection (8 cases). Infectious keratitis preceded endophthalmitis in 32 cases. Thirty-one patients developed endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection, and eight cases were related to ocular trauma.

Table 2.

Etiology of exogenous endophthalmitis

| Etiology | n |

|---|---|

| Postoperative | 102 |

| Post-cataract | 52 |

| Bleb-related | 18 |

| Post-PK | 11 |

| Post-PPV | 10 |

| Glaucoma drainage device-related | 8 |

| Post-scleral buckle | 1 |

| Post-DSEK | 1 |

| Post-keratoprosthesis | 1 |

| Mectious keratitis-related | 32 |

| Post-injection | 31 |

| Trauma | 8 |

| Total | 173 |

Microbiological analysis of endogenous and exogenous endophthalmitis

In endogenous endophthalmitis cases, 70 patients (63.1%) were culture-positive, while 41 cases were deemed culture-negative (Table 2). The culture data were unobtainable in two patients. There were 77 organisms identified from 70 culture-positive patients due to seven polymicrobial cases. Gram-positive organisms (41 out of 77) were the most common causative group for endogenous endophthalmitis, followed by fungal (23 out of 77) and gram-negative (13 out of 77). Candida species was the most common causative organism in endogenous endophthalmitis (23 isolates). In exogenous endophthalmitis cases, causative organisms were identified in 99 cases (59.6%), and there were 67 culture-negative cases. The culture data were unobtainable in seven patients. There were 106 organisms cultured from 99 culture-positive patients, as there were nine polymicrobial cases. As a group, gram-positive organisms were found in 79 cases, which was higher than the gram-negative group (22 cases) and the fungal isolate group (7 cases). Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was the most common organism discovered in exogenous cases (30 isolates). Although visual acuity was unobtainable for sedated patients and those with underlying mental status changes, titere was a trend toward poorer visual outcomes in bacterial cases for both groups.

Survival with endogenous versus exogenous endophthalmitis

Figure 2 illustrates the one-year Kaplan-Meier plot for patients with endogenous and exogenous infections. Patients with endogenous cases had considerable mortality as early as 1 month after diagnosis (7 deaths out of 113 compared to 2 deaths out of 173). At no point in the first year after diagnosis did exogenous cases have higher mortality than endogenous cases, despite being a significantly older population. At the end of the first year after diagnosis, mortality was 14 out of 113 endogenous cases (12.4%) compared to 6 out of 173 exogenous cases (3.5%). Overall, endogenous endophthalmitis cases had significantly higher mortality than exogenous ones within the first year of diagnosis (p = 0.0034).

Fig. 2.

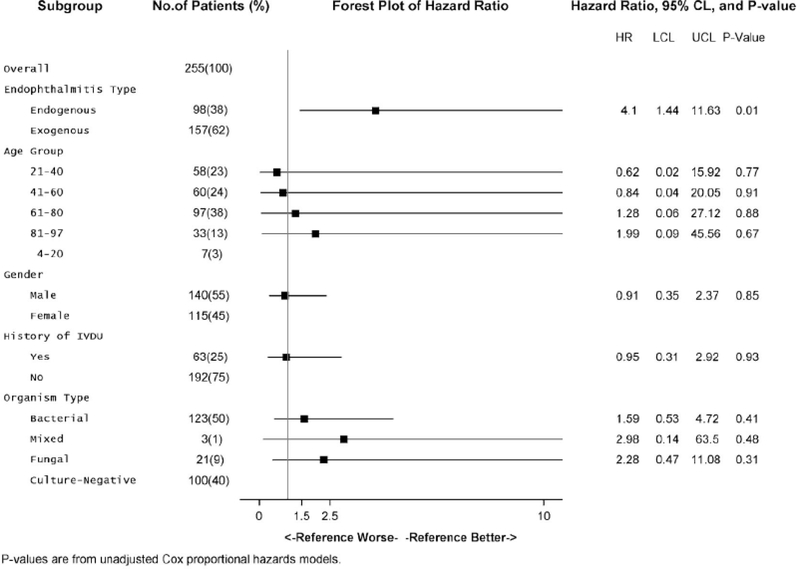

Unadjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Model. Hazard ratios reflect the risk of mortality without standardization for the other variables in the model. The only variable with a significant impact on mortality was the type of endophthalmitis (endogenous vs. exogenous) with a hazard ratio of 4.1 (p = 0.01)

Effects of age, gender, organism, and history of IVDU

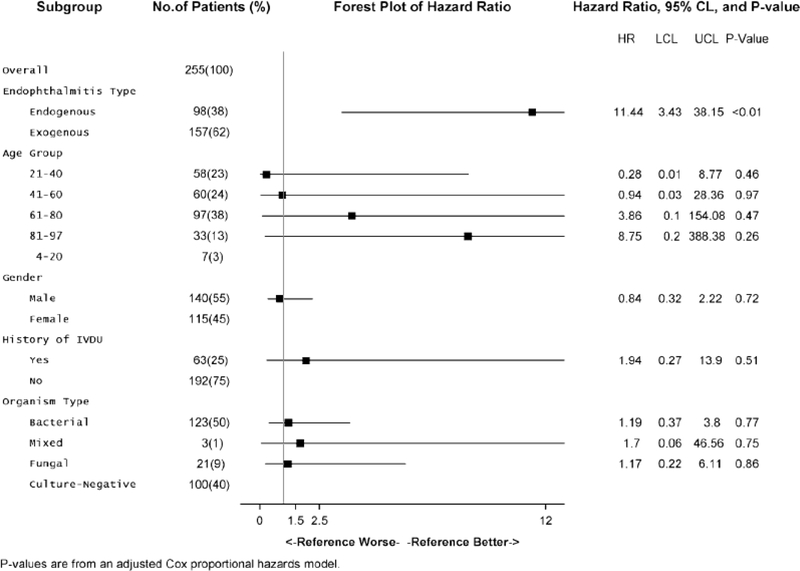

The unadjusted Cox proportional hazards model in Fig. 3 shows that endogenous endophthalmitis has significantly higher mortality than the exogenous form (HR = 3.78; Cl 1.453–9.842) (p < 0.01). When patients were separated into age groups of 21–40, 41–60, 61–80, and 81–100, none of these age groups had significantly different hazard ratios. When organisms were grouped broadly as bacterial, fungal, mixed (bacterial and fungal), or culture-negative, none of these hazard ratios were statistically significant either. The hazard ratios for age group, gender, and history of IVDU were still not significantly different when an adjusted multiple Cox proportional hazards model was employed (Fig. 4). However, the hazard ratio for endogenous infections versus the exogenous group increased to 10.91 (Cl 3.544–33.595) when the other variables of age, gender, organism type, and IVDU were controlled (p < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Multiple Cox Proportional Hazards Model. Hazard ratios reflect the risk of mortality with standardization for the other variables in the model. Endogenous endophthalmitis is a more significant risk factor, with a hazard ratio of 11.44, when all other variables are controlled (p < 0.01)

Fig. 4.

Multiple Cox Proportional Hazards Model. Hazard ratios reflect the risk of mortality with standardizaron for the other variables in the model. The type of endophthalmitis (endogenous vs. exogenous) becomes a more significant risk factor, with a hazard ratio of 10.91, when all other variables are controlled (p < 0.01)

Discussion

Many of the baseline characteristics of the population used in the study are similar to precedent studies [3, 4, 6–8]. However, while previous studies have suggested that around 2–8% of endophthalmitis cases are endogenous, these infections accounted for 39.5% among this WV population [15, 17]. The exogenous endophthalmitis population (mean age of 65) is considerably older than the endogenous endophthalmitis population (mean age of 44). While the most common age group for endogenous infections was 21–40 (likely related to being the age group with highest rates of IVDU), most endophthalmitis cases overall and most exogenous cases were in the age group of 61–80. This disparity might have occurred because this was the age group within which most patients with post-cataract and postoperative exogenous endophthalmitis presented. While there was no strong gender disparity among exogenous infections, males were overrepresented among endogenous cases. Males had a correspondingly higher rate of IVDU. Similar to previous studies, this study showed a much higher rate ofIVDU in the endogenous group (63.7%) than in the exogenous group (1.2%) (p < 0.001) [8,9]. Between 2009 and 2019, the number of cases of endophthalmitis steadily increased within both endogenous and exogenous groups (Fig. 1). While partly related to the expansion of the opioid epidemic, part of this effect was due to an increase in exogenous infections and may be related to population growth, increasing rates of intraocular surgery and intravitreal injections, or greater numbers of patients using WVU facilities due to changing referral patterns or healthcare system consolidation.

In this study. the rate of culture positivity was 63.1% in the endogenous group, similar to 64.1% reported by Connell et al. [15]. In exogenous endophthalmitis cases, the culture positivity rate was 59.6%, which was only slightly higher than the previously reported rate of 47% [16]. The prevalence of fungal infection was higher in the endogenous group (29.9%) than the exogenous group (6.5%). However, the fungal organisms were less prevalent in the endogenous group when compared to the rates from other studies, in which the rate ranged from 53 to 66% [15, 17, 18]. This may be because blood culture samples were obtained after IVDU, resulting in transient fungemia and a relatively high number of culture-negative cases in our study [19]. Similar to previous studies. gram-positive organisms were the major group associated with exogenous infection, Coagulase-negative staphylococcus being the most common agent [20–22].

The Kaplan–Meier plot (Fig. 2) displays 1-year mortality rates that are relatively high for endophthalmitis overall, with endogenous morality in particular over 10%. Mortality was higher in the endogenous group than in the exogenous group at all points during the lirst year after diagnosis. Because the median age among the exogenous endophthalmitis population is 3 decades older, the survival curve for this population would be expected to decline within 10–15 years due to older age and associated comorbidities. The younger endogenous population that survives could potentially live many more decades, so there is possibly a point at which the survival curves of endogenous and exogenous infections intersect. Identifying this critical intersection point presents a challenge because extending the Kaplan–Meier curve requires excluding patients who were diagnosed in recent years (and have not been followed for the full survival period). Our data suggest that this hypothesized intersection point does not occur within the first year, and endogenous endophthalmitis was associated with higher 1-year mortality despite occurring in a population with a median age that is 3 decades younger.

The Cox proportional hazards (CPH) model showed that age, gender, organism type (bacterial vs. fungal vs. culture-negative), and history of IVDU did not have a significant effect on mortality. The only variable in this study with a significant impact on mortality was the type of endophthalmitis (endogenous vs. exogenous). Our findings suggest that although IVDU can be part of the causal pathway that leads to endogenous endophthalmitis, developing endogenous endophthalmitis via IVDU does not confer greater mortality risk than developing endogenous endophthalmitis through other means. It is also possible there were not enough deaths of IV drug users and non-users within the endogenous group to detect statistical significance. When comparing the unadjusted and adjusted CPH models, the type of endophthalmitis becomes a more significant risk factor when all other variables are controlled. Endogenous infections have greater hazard ratios when age, gender, and history of IVDU are controlled. Presumably, this could be attributed to age. implying that endogenous infections are even more fatal than the unadjusted data suggest because it has higher mortality among a younger population.

The limitations of this study include selection bias inherent in retrospective studies. The number of IVDU cases may be underestimated by reluctance to admit to drug use or failure to document drug use data in the EHR. A comparison of differences in the timeline of presentation was not possible due to lack of standardized screening processes in patients with septicemia and incomplete data from patients transferred to WVU from other facilities. This study only investigated mortality in the first year after diagnosis and the methods we employed may not identify all mortality cases. The treatment regimen was not uniform throughout the study and treatment outcomes data were limited by loss to follow-up, especially in the IVDU group. The results may not be generalizable to other populations and are not intended to guide management of individual patients.

Altogether, this study demonstrates that the West Virginia population has a higher proportion of endogenous endophthalmitis compared to national data. Prompt systemic treatments and close monitoring are required for patients with endogenous endophthalmitis, since endogenous infections are associated with higher mortality rates even within the first year. Other variables including age, gender, organism type, and history of IVDU have less, if any, modifying effect on mortality.

Acknowledgments

Funding The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Availability of data and material All data are available upon request.

Code availability Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical approval This study was granted a waiver and complies with all tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Consent for publication All information is anonymized and the submission does not include images that may identify the person.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affihations.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey Desilets, Ross Eye Institute, 1176 Main St., Buffalo, NY, USA.

Chang Sup Lee, WVU Eye Institute, 1 Medical Center Drive, Morgantown, WV, USA.

Wei Fang, West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute, WVU Health Sciences Center Erma Byrd Biomedical Research Center, 1 Medical Center Drive, Morgantown, WV, USA.

David M. Hinkle, WVU Eye Institute, 1 Medical Center Drive, Morgantown, WV, USA Tulane University School of Medicine, 131 S. Robertson Street, 12th floor #8069, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA.

References

- 1.Relhan N, Forster RK, Flynn HW Jr (2018) Endophthalmitis: then and now. Am J Ophthalmol. 187:xx–xxvii [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crosby N, Polkinghome PJ, Khn B, McGhee CN, Welch S, Riley A (2018) Mortality after endophthahnitis following contemporary phacoemulsification cataract surgery. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 46(8):903–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong JS, Chan TK, Lee HM, Chee SP (2000) Endogenous bacterial endophthahnitis: an east Asian experience and a reappraisal of a severe ocular affliction. Ophthahnology 107(8):1483–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjerrum SS, la Cour M (2017) 59 eyes with endogenous endophthahnitis- causes, outcomes and mortality in a Danish population between 2000 and 2016. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 255(10):2023–2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guber J, Saeed MU (2015) Presentation and outcome of a cluster of patients with endogenous endophthahnitis: a case series. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 232(4):595–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solborg Bjerrum S, Hamoudi H, Friis-Møller A, la Cour M (2016) A prospective study on the clinical and microbiological spectrum of endophthahnitis in a specific region in Denmark. Ophthahnologica 235(l):26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson TL, Paraskevopoulos T, Georgalas I (2014) Systematic review of 342 cases of endogenous bacterial endophthahnitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 59(6):627–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weng TH, Chang HC, Chung CH, Lin EH, Tai MC, Tsao CH, Chien KH, Chien WC (2018) Epidemiology and mortahty-related prognostic factors in endophthahnitis. Ihvestig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 59(6):2487–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung CY, Wong ES, Liu CCH, Wong MOM, Li KKW (2017) Clinical features and prognostic factors of Klebsiella endophthahnitis-10-year experience in an endemic region. Eye (Lond) 31(11):1569–1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung J, Lee J, Yu SN, Khn YK, Lee JY, Sung H, Khn MN, Khn SH, Lee SO, Choi SH, Woo JH, Lee JY, Khn YS, Chong YP (2016) Incidence and risk factors of ocular infection caused by staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60(4):2012–2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modjtahedi BS et al. (2017) Intravenous drug use-associated endophthahnitis. Ophthalmol Retina 1(3):192–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mh TA, Papudesu C, Fung W, Hinkle DM (2021) Incidence of drug use-related endogenous endophthahnitis hospitalizations in the United States, 2003 to 2016. JAMA Ophthalmol. 10.1001/jamaophthahnol.2020.4741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, WUson N, Baldwin G (2019) Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67:1419–1427 10.15585/mmwr.mm675152el [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith Conor. WVU Medicine highlights 2017 achievements. WV News. https://www.wvnews.com/statejoumal/news/wvu-medicine-highhghts-2017-achievements/article_eeec7768-cda5-5fl5-ab7e-fdc916cf844e.html [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connell PP, O’Neill EC, Fabinyi D et al. (2011) Endogenous endophthahnitis: 10-year experience at a tertiary referral centre. Eye (Lond) 25(l):66–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramakrishnan R, Bharathi MJ, Shivkumar C et al. (2009) Microbiological profile of culture-proven cases of exogenous and endogenous endophthahnitis: a 10-year retrospective study. Eye (Lond) 23(4):945–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiedler V, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Davis JL, Benz MS, Miller D (2004) Culture-proven endogenous endophthahnitis: clinical features and visual acuity outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 137(4):725–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binder MI, Chua J, Kaiser PK, Procop GW, Isada CM (2003) Endogenous endophthahnitis: an 18-year review of culture-positive cases at a tertiary care center. Medicine (Baltimore) 82(2):97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durand ML (2017) Bacterial and fungal endophthahnitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 30(3):597–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han DP, Wisniewski SR, Wilson LA et al. (1996) Spectrum and susceptibilities of microbiologic isolates in the Endophthahnitis Vitrectomy Study [published correction appears in Am J Ophthalmol 1996 Dec; 122(6):920]. Am J Ophthalmol 122(1):1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gentile RC, Shukla S, Shah M et al. (2014) Microbiological spectrum and antibiotic sensitivity in endophthahnitis: a 25-year review. Ophthahnology 121(8):1634–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benz MS, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Unonius N, Miller D (2004) Endophthahnitis isolates and antibiotic sensitivities: a 6-year review of culture-proven cases. Am J Ophthalmol 137(l):38–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]