Abstract

The fungi of the order Onygenales can cause important human infections; however, their taxonomy and worldwide occurrence is still little known. We have studied and identified a representative number of clinical fungi belonging to that order from a reference laboratory in the USA. A total of 22 strains isolated from respiratory tract (40%) and human skin and nails (27.2%) showed a malbranchea-like morphology. Six genera were phenotypically and molecularly identified, i.e. Auxarthron/Malbranchea (68.2%), Arachnomyces (9.1%), Spiromastigoides (9.1%), and Currahmyces (4.5%), and two newly proposed genera (4.5% each). Based on the results of the phylogenetic study, we synonymized Auxarthron with Malbranchea, and erected two new genera: Pseudoarthropsis and Pseudomalbranchea. New species proposed are: Arachnomyces bostrychodes, A. graciliformis, Currahmyces sparsispora, Malbranchea gymnoascoides, M. multiseptata, M. stricta, Pseudoarthropsis crassispora, Pseudomalbranchea gemmata, and Spiromastigoides geomycoides, along with a new combination for Malbranchea gypsea. The echinocandins showed the highest in vitro antifungal activity against the studied isolates, followed by terbinafine and posaconazole; in contrast, amphotericin B, fluconazole, itraconazole and 5-fluorocytosine were less active or lacked in vitro activity against these fungi.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s43008-021-00075-x.

KEYWORDS: Antifungals, Arachnomycetales, Auxarthron, Clinical fungi, Malbranchea, Onygenales, New taxa

INTRODUCTION

The order Onygenales includes medically important fungi, such as the dermatophytes and the thermally dimorphic systemic pathogens (Histoplasma, Coccidioides and related fungi), which are naturally present in keratinous substrates, in soil, and in freshwater sediments (Currah 1985, 1994; Doveri et al. 2012; Dukik et al. 2017; Hubálek 2000; Hubka et al. 2013; Sharma and Shouche 2019). The genus Malbranchea, which is characterized by the production of alternate arthroconidia in branches from the vegetative hyphae, is one of the genus-form of this order; however, it’s pathogenic role in human infections is little known. Only a few cases of fungal infections by species of this genus have been described: Malbranchea dendritica has been recovered from lungs, spleen and liver of mice (Sigler and Carmichael 1976), Malbranchea pulchella has been suggested as a possible cause of sinusitis (Benda and Corey 1994), and M. cinnamomea was recovered from dystrophic nails in patients with underlying chronic illnesses (Lyskova 2007, Salar and Aneja 2007). More recently, Malbranchea spp. have been proposed as one of the causative agents of Majocchi’s granuloma (Govind et al. 2017; Durdu et al. 2019). In a study of 245 patients with fungal saprophytic infections of nails and skin, Malbranchea spp. were isolated in 1% of skin samples (Lyskova 2007). Other studies demonstrated the coexistence (0.3% of the cases) of Malbranchea spp. with the primary pathogen patients with tuberculosis (Benda and Corey 1994; Yahaya et al. 2015).

Malbranchea was erected by Saccardo in 1882 for a single species, Malbranchea pulchella. It is characterized by alternate arthroconidia originating in curved branches from the vegetative hyphae, which developed on the surface of wet cardboard collected by A. Malbranche in Normandy, France (Fig. 1). Cooney and Emerson reviewed the genus in 1964, providing an appropriated description for mesophilic (M. pulchella) and thermophilic (Malbranchea sulfurea) species. In a more recent revision by Sigler and Carmichael (1976) 12 species were accepted, while a close relationship with the genus Auxarthron (family Onygenaceae, order Onygenales) was reported, i.e. the species Auxarthron conjugatum forms a malbranchea-like asexual morph, and Malbranchea albolutea produces a sexual morph related to Auxarthron. Also, Sigler and co-workers (2002) connected Malbranchea filamentosa with Auxarthron based on molecular studies, and also reported the production of fertile ascomata after an in vitro mating of several sexually compatible strains of M. filamentosa. The genus Auxarthron produces reddish brown, appendaged gymnothecial ascomata with globose prototunicate 8-spored asci, and globose or oblate, reticulate ascospores (Solé et al. 2002). Some species of this genus, such as Auxarthron ostraviense and A. umbrinum have been reported as producing onychomycosis in humans (Hubka et al. 2013), and Auxarthron brunneum, A. compactum and A. zuffianum were also isolated from the lungs of kangaroo rats, A. conjugatum from lungs of rodents, and A. umbrinum from lung of dogs, bats and rodents (Orr et al. 1963; Kuehn et al. 1964).

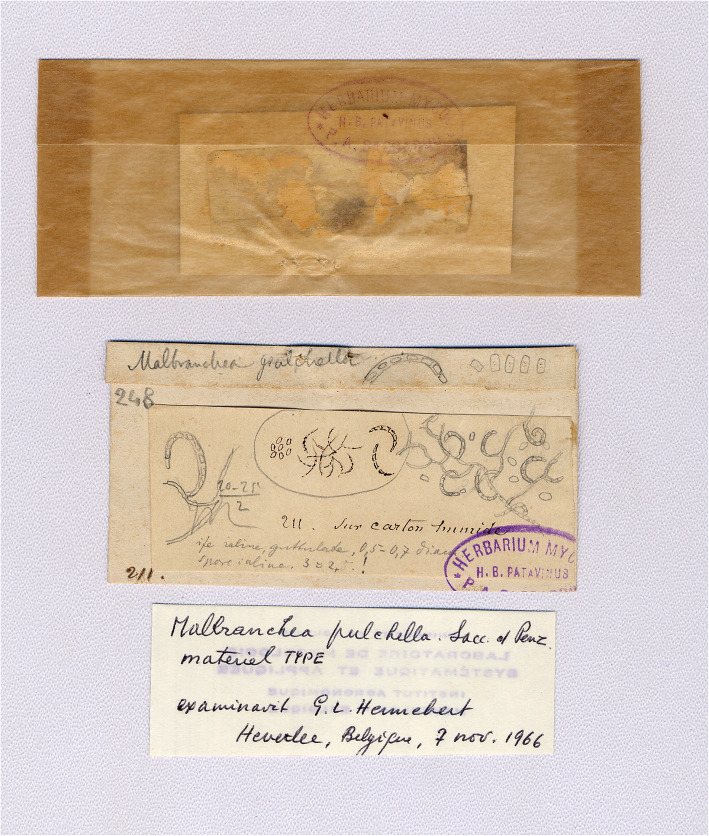

Fig. 1.

Malbranchea pulchella Sacc. & Penzig. Holotype and lectotype. Black ink drawings by A. Malbranche, and pencil drawings by P. A. Saccardo (credits: Rosella Marcucci, erbario micologico di Pier Andrea Saccardo, Università di Padova, Italy)

Malbranchea-like asexual morphs are also present in other taxa of ascomycetes. The genus Arachnomyces (family Arachnomycetaceae, order Arachnomycetales; Malloch and Cain 1970, Guarro et al. 1993), characterized by the production of brightly coloured cleistothecial ascomata bearing setae, and by the production of an onychocola-like (Sigler et al. 1994) or a malbranchea-like (Udagawa and Uchiyama 1999) asexual morph, have been also implicated in animal and human infections. Specifically, Arachnomyces nodosetosus and Arachnomyces kanei have been reported as causing nail and skin infections in humans (Sigler and Congly 1990; Sigler et al. 1994; Campbell et al. 1997; Contet-Audonneau et al. 1997; Kane et al. 1997; Koenig et al. 1997; Gupta et al. 1998; Erbagci et al. 2002; Gibas et al. 2002; Llovo et al. 2002; O’Donoghue et al. 2003; Gibas et al. 2004; Stuchlík et al. 2011; Järv 2015; Gupta et al. 2016). More recently, Arachnomyces peruvianus has been reported to cause cutaneous infection (Brasch et al. 2017) and A. glareosus was isolated from nail and skin samples (Gibas et al. 2004; Sun et al. 2019).

The recently described Spiromastigoides albida, isolated from human lung in USA (Stchigel et al. 2017), also produces a malbranchea-like asexual morph. This genus (family Spiromastigaceae, Onygenales) produces orange gymnothecial ascomata with contorted to coiled appendages and pitted and lenticular ascospores (Kuehn and Orr 1962; Uchiyama et al. 1995; Unterainer et al. 2002; Hirooka et al. 2016).

Due to the limited knowledge of Malbranchea and their relatives in human infections, we have studied phenotypically and molecularly a set of malbranchea-like fungal strains from clinical specimens received in a fungal reference centre in the USA. Phylogenetic study and an antifungal susceptibility testing were also carried out.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains

Twenty-two malbranchea-like fungal strains (19 from human specimens and three from animals) from different locations in USA were included in this study. The strain number, anatomical source, and geographic origin of the specimens are listed in Table 1. They were provided by the Fungus Testing Laboratory of the University of Texas Health Science Centre at San Antonio (UTHSC; San Antonio, Texas, USA).

Table 1.

DNA barcodes used to build the phylogenetic tree

| Species | Strainsa | GenBank accession #b | Geographic origin and source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITSc | LSUc | |||

| Ajellomyces capsulatus | UAMH 3536 d | AF038354 | AF038354 | Alberta, Canada; woman, 25-years-old, biopsy of right middle lobe lung |

| Amauroascus niger | ATCC 22339 | MH869547 | AY176706 | California, U.S.A.; soil |

| Amauroascus purpureus | IFO 32622 d | AJ271564 | AY176707 | Japan; soil |

| Amauroascus volatilis-patellis | CBS 249.72 d | MH860467 | MH872189 | Utah, U.S.A.; soil |

| Aphanoascus mephitalis | ATCC 22144 | MH859941 | AY176725 | Ontario, Canada; wolf dung |

| Arachniotus verruculosus | CBS 655.71 | NR_145221 | AB040684 | Utah, U.S.A.; soil |

| Arachnomyces bostrychodessp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-91 = FMR 17685 = CBS 146926d | LR701765 | LR701766 | Texas, U.S.A.; human scalp |

| Arachnomyces glareosus | CBS 116129 d | AY624316 | FJ358273 | Alberta, Canada; man, 30-years-old, thumb nail |

| Arachnomyces graciliformissp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-97 = FMR 17691 = CBS 146927d | LR743667 | LR743668 | Massachusetts, U.S.A.; animal bone |

| Arachnomyces gracilis | UAMH 9756 d | AY123779 | – | Uganda; termitarium soil |

| Arachnomyces jinanicus | CGMCC3.14173 d | KY440749 | KY440752 | Jinan, China; pig farm soil |

| Arachnomyces kanei | UAMH 5908 d | AY123780 | – | Toronto, Canada; human nail |

| Arachnomyces minimus | CBS 324.70 d | AY123783 | FJ358274 | Ontario, Canada; decaying wood |

| Arachnomyces nitidus | UAMH 10536 | – | AB075351 | Israel; twigs |

| Arachnomyces nodosetosus | CBS 313.90 d | AY123784 | AB053452 | Saskatchewan, Canada; woman, 67-years-old, onychomycosis |

| Arachnomyces peruvianus | CBS 112.54 d | MF572315 | MH868792 | Peru; Globodera rostochiensis cyst |

| Arachnomyces pilosus | CBS 250.93 d | MF572320 | MF572325 | Catalonia, Spain; river sediment |

| Arachnomyces scleroticus | UAMH 7183 d | AY123785 | – | Sulawesi, Indonesia; poultry farm soil |

| Arthroderma curreyi | CBS 353.66 d | MH858822 | MH870459 | UK; unknown |

| Arthroderma onychocola | CBS 132920 d | KT155794 | KT155124 | Prague, Czech Republic; human nail |

| Ascosphaera apis | CBS 252.32 | – | AY004344 | København, Denmark; A. mellifera |

| Ascosphaera subglobosa | A.A. Wynns 5004 (C) d | NR_137060 | HQ540517 | Utah, U.S.A.; pollen provisions of M. rotundata |

| Auxarthronopsis bandhavgarhensis | NFCCI 2185 d | HQ164436 | NG_057012 | Bandhavgarh, India; soil |

| Auxarthronopsis guizhouensis | CGMCC3.17910 d | KU746668 | KU746714 | Guizhou, China; air |

| Blastomyces percusus | CBS 139878 d | NR_153647 | KY195971 | Israel; human granulomatous lesions |

| Canomyces reticulatus | MCC 1486 d | MK340501 | MK340502 | Maharashtra, India; soil |

| Chrysosporium keratinophilum | CBS 392.67 | MH859002 | AY176730 | New Zealand; soil |

| Chrysosporium tropicum | MUCL 10068 d | MH858134 | AY176731 | Guadalcanal, Solomon islands; woollen overcoat |

| Currahmyces indicus | MCC 1548 d | MK340498 | MK340499 | Maharashtra, India; hen resting area |

| Currahmyces sparsisporasp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-89 = FMR 17683 = CBS 146929d | LR723272 | LR723273 | Florida, U.S.A.; human sputum |

| Gymnoascus reesii | CBS 410.72 | MH860507 | MH872224 | California, U.S.A.; soil |

| Helicoarthrosporum mellicola | CBS 143838 d | LR761645 | LT906535 | Granada, Spain; honey |

| Helicoarthrosporum mellicola | FMR 15673 | LR761646 | LT978462 | Valencia, Spain; honey |

| Malbranchea albolutea | UTHSCSA DI18-85 = FMR 17679 | LR701834 | LR701835 | Texas, U.S.A.; human BAL |

| Malbranchea albolutea | UTHSCSA DI18-95 = FMR 17689 | LR701836 | LR701837 | Texas, U.S.A.; human BAL |

| Malbranchea albolutea | CBS 125.77 d | MH861039 | MH872808 | Utah, U.S.A.; soil |

| Malbranchea aurantiaca | UTHSCSA DI18-94 = FMR 17688 | LR701824 | LR701825 | California, U.S.A.; animal |

| Malbranchea aurantiaca | UTHSCSA DI18-88 = FMR 17682 | LR701826 | LR701827 | Texas, U.S.A.; animal skin lesion |

| Malbranchea aurantiaca | CBS 127.77 d | NR_157447 | AB040704 | Utah, U.S.A.; culture contaminant |

| Malbranchea californiensis | ATCC 15600 d | MH858121 | NG_056947 | California, U.S.A.; dung of pack rat |

| Malbranchea chinense | CGMCC3.19572 | MK329076 | MK328981 | Guangxi, Luotian Cave, China; Soil |

| Malbranchea chrysosporioidea | CBS 128.77 d | AB361632 | AB359413 | Arizona, U.S.A.; soil |

| Malbranchea circinata | ATCC 34526 d | MN627784 | MN627782 | Utah, U.S.A.; soil |

| Malbranchea conjugata | UTHSCSA DI18-105 = FMR 17699 | LR701828 | LR701829 | Florida, U.S.A.; human lung tissue |

| Malbranchea conjugata | UTHSCSA DI18-103 = FMR 17697 | LR701830 | LR701831 | Texas, U.S.A.; human BAL |

| Malbranchea conjugata | CBS 247.58 | NR_121475 | HF545313 | Arizona, U.S.A.; soil |

| Malbranchea dendritica | CBS 131.77 d | AY177310 | AB359416 | Utah, U.S.A.; soil |

| Malbranchea filamentosa | CBS 581.82 d | NR_111136 | AB359417 | Argentina; soil |

| Malbranchea flava | CBS 132.77 d | AB361633 | AB359418 | California, U.S.A.; soil |

| Malbranchea flavorosea | ATCC 34529 d | NR 158362 | AB359419 | California, U.S.A.; soil |

| Malbranchea flocciformis | UTHSCSA DI18-104 = FMR 17698 | LR701822 | LR701823 | Texas, U.S.A.; human skin |

| Malbranchea flocciformis | CBS 133.77 d | AB361634 | AB359420 | France; saline soil |

| Malbranchea fulva | CBS 135.77 d | NR_157444 | AB359422 | Utah, U.S.A.; air |

| Malbranchea gymnoascoidessp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-87 = FMR 17681 = CBS 146930d | LR701757 | LR701758 | Texas, U.S.A.; human BAL |

| Malbranchea guangxiense | CGMCC3.19634 | MK329080 | MK328985 | Guangxi, E’gu Cave, China; Soil |

| Malbranchea kuehnii | CBS 539.72 d | NR_103573 | NG_056928 | Unkown; dung |

| Malbranchea longispora | FMR 12768 d | HG326873 | HG326874 | Beija, Portugal; soil |

| Malbranchea multiseptatasp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-101 = FMR 17695 = CBS 146931d | LR701759 | LR701760 | Texas, U.S.A.; human BAL |

| Malbranchea ostraviense | CBS 132919 d | NR_121474 | – | Ostrava, Czech Republic; fingernail sample |

| Malbranchea pseudauxarthron | IFO 31701 = CBS 657.71 = ATCC 22158 = NRRL 5132 | MH860293 | KY014424 | Utah, U.S.A.; domestic rabbit dung |

| Malbranchea pulchella | CBS 202.38 | AB361638 | AB359426 | Italy; unknown |

| Malbranchea strictasp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-86 = FMR 17680 = CBS 146932d | LR701638 | LR701639 | Florida, U.S.A.; human nail |

| Malbranchea sp.e | CBS 319.61 | MH858065 | MH869635 | California, U.S.A.; soil |

| Malbranchea umbrina | UTHSCSA DI18-106 = FMR 17700 | LR701814 | LR701815 | Colorado, U.S.A.; human BAL |

| Malbranchea umbrina | UTHSCSA DI18-107 = FMR 17701 | LR701816 | LR701817 | Colorado, U.S.A.; human sinus |

| Malbranchea umbrina | UTHSCSA DI18-100 = FMR 17694 | LR701818 | LR701819 | Baltimore, U.S.A.; human wound |

| Malbranchea umbrina | UTHSCSA DI18-99 = FMR 17693 | LR701820 | LR701821 | Washington DC, U.S.A.; human nail |

| Malbranchea umbrina | CBS 105.09 d | MH854591 | MH866116 | UK; soil |

| Malbranchea umbrina | CBS 226.58 | MH857765 | MH869296 | Unknown |

| Malbranchea umbrina | CBS 261.52 | MH857026 | MH868556 | UK; soil |

| Malbranchea zuffiana | UTHSCSA DI18-96 = FMR 17690 | LR701832 | LR701833 | Washington DC, U.S.A.; human wound |

| Malbranchea zuffiana | CBS 219.58 d | MH869293 | AY176712 | Texas, U.S.A.; prairie dog lung |

| Nannizziopsis guarroi | CBS 124553 d | MH863384 | MH874904 | Barcelona, Spain; iguana skin |

| Nannizziopsis vriesii | ATCC 22444 d | AJ131687 | AY176715 | The Netherlands; Ameiva (lizard) skin and lung |

| Neogymnomyces demonbreunii | CBS 427.70 | AJ315842 | AY176716 | Missouri, U.S.A.; unknown |

| Onychocola canadensis | CBS 109438 | – | KT154998 | Italy; nail and skin scrapings |

| Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | UAMH 8037 d | AF038360 | AF038360 | Alberta, Canada; man, 59-years-old, lung biopsy |

| Pseudoarthropsis cirrhata | CBS 628.83 d | – | NG_060792 | Schiphol, The Netherlands; wall sample |

| Pseudoarthropsis crassisporasp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-98 = FMR 17692 = CBS 146928d | LR701763 | LR701764 | Minnesota, U.S.A.; human BAL |

| Pseudomalbranchea gemmatagen. nov. et sp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-90 = FMR 17684 = CBS 146933d | LR701761 | LR701762 | Florida, U.S.A.; human BAL |

| Pseudospiromastix tentaculata | CBS 184.9210536 | AY527406 | LN867603 | Hiram, Somalia; soil |

| Renispora flavissima | CBS 708.79 d | AF299348 | AY176719 | Kansas, U.S.A.; soil in barn housing M. velifer |

| Spiromastigoides alatosporus | CBS 457.73 d | MH860740 | AB075342 | Madras, India; V. sinensis rhizosphere |

| Spiromastigoides albina | CBS 139510 d | LN867606 | LN867602 | Texas, U.S.A.; human lung biopsy |

| Spiromastigoides asexualis | CBS 136728 d | KJ880032 | LN867603 | Phoenix, U.S.A.; discospondylitis material from a German shepherd dog |

| Spiromastigoides curvata | JCM 11275 d | KP119631 | KP119644 | México; contaminant of a strain of Histoplasma capsulatum |

| Spiromastigoides frutex | CBS 138266 d | KP119632 | KP119645 | Nayarit, Mexico; house dust, rental studio |

| Spiromastigoides geomycoidessp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-92 = FMR 17686 | LR701769 | LR701770 | Minnesota, U.S.A.; human blood |

| Spiromastigoides geomycoidessp. nov. | UTHSCSA DI18-102 = FMR 17696 = CBS 146934d | LR701767 | LR701768 | Illinois, U.S.A.; human skin foot |

| Spiromastigoides gypsea | CBS 134.77 d | KT155798 | NG_063935 | California, U.S.A.; soil |

| Spiromastigoides kosraensis | CBS 138267 d | KP119633 | KP119646 | Kosrae, Micronesia; house dust |

| Spiromastigoides pyramidalis | CBS 138269 d | KP119636 | KP119649 | Australia; house dust |

| Spiromastigoides sugiyamae | JCM 11276 d | LN867608 | AB040680 | Japan; soil |

| Spiromastigoides warcupii | CBS 576.63 d | LN867609 | AB040679 | Australia; soil |

| Strongyloarthrosporum capsulatus | CBS 143841 d | LR760230 | LT906534 | Toledo, Spain; honey |

| Trichophyton bullosum | CBS 363.35 d | NR_144895 | NG_058191 | Unkown |

| Uncinocarpus reesii | ATCC 34533 | MH861035 | AY176724 | Australia; feather |

aATCC American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, USA, BCCM/MUCL Mycothèque de l’Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, CBS Culture collection of the Westerdijk Biodiversity Institute, Utrech, The Netherlands, CGMCC China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center, Beijing, China, FMR Facultat de Medicina, Reus, Spain, IFO Institute for Fermentation Culture Collection, Osaka, Japan, JCM Japan Collection of Microorganisms, Tsukuba, Japan, MCC Microbial Culture Collection, Universite of Pune Campus Ganeshkhind, India, NFCCI National Fungal Culture Collection of India, Maharastra, India, UAMH University of Alberta Microfungus Collection and Herbarium, Alberta, Canada, UTHSC Fungus Testing Laboratory, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, United States

bStrains studied by us are indicated in bold

cITS internal transcribed spacer region 1 and 2 including 5.8S nrDNA, LSU large subunit of the nrRNA gene

dEx-type strain

eStrain formerly assigned to Auxarthron thaxteri (a species synonymized with Malbranchea umbrina)

Phenotypic study

For cultural characterization, suspensions of conidia were prepared in a semi-solid medium (0.2% agar; 0.05% Tween 80) and inoculated onto phytone yeast extract agar (PYE; Becton, Dickinson & Company, Sparks, MD, USA; Carmichael and Kraus 1959), potato dextrose agar (PDA; Pronadisa, Madrid, Spain; Hawksworth et al. 1995), oatmeal agar (OA; 30 g of filtered oat flakes, 15 g agar-agar, 1 L tap water; Samson et al. 2010), bromocresol purple-milk solids-glucose agar (BCP-MS-G; 80 g skim milk powder, 40 g glucose, 10 mL of 1.6% of bromocresol purple in 95% ethanol, 30 g agar-agar,1 L tap water; Kane and Smitka 1978), and test opacity tween medium (TOTM; 10 g bacteriological peptone, 5 g NaCl, 1 g CaCl2, 5 mL Tween, 5 mL Tween 80, 15 g agar-agar, 1 L tap water; Slifkin 2000). Colonies were characterized after 14 days at 25 °C in the dark. Potato dextrose agar (PDA) was used to determine the cardinal temperatures of growth. Colour notations were taken according to Kornerup and Wanscher (1978). Christensen’s urea agar (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany; Christensen 1946) was inoculated and incubated for 4 days at 25 °C in the dark to detect the production of urease. Cycloheximide tolerance was tested growing the fungal strains on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA; Pronadisa, Spain) supplemented with 0.2% cycloheximide (Sigma, USA) at 30 °C for two wk. Fungal tolerance to NaCl was evaluated on SDA adding 3, 10 and 20% w/w NaCl, with the same incubation conditions as previously described. The microscopic structures were characterized and measured from wet mountings of slide cultures, using water and 60% lactic acid. Photo micrographs were taken using a Zeiss Axio-Imager M1 light microscope (Oberkochen, Germany) with a DeltaPix Infinity X digital camera using Nomarski differential interference contrast. The descriptions of the taxonomical novelties were submitted to MycoBank (https://www.mycobank.org/; Crous et al. 2004).

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

Total DNA was extracted as previously described (Valenzuela-Lopez et al. 2018), and the following phylogenetic markers were amplified: the internal transcribed spacers (ITS) (ITS5/ITS4 primers; White et al. 1990, and a fragment of the large subunit (LSU) gene (LR0R/LR5 primers; Vilgalys and Hester 1990; Rehner and Samuels 1994) of the nrDNA. Amplicons were sequenced at Macrogen Europe (Macrogen Inc., Madrid, Spain) using the same pair of primers. Consensus sequences were obtained by SeqMan software v. 7 (DNAStar Lasergene, Madison, WI, USA). Sequences generated in this work were deposited in GenBank (Table 1).

Phylogenetic analysis

A preliminary molecular identification of the isolates was carried out with ITS and LSU nucleotide sequences using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and only the sequences of ex-type or reference strains from GenBank were included for identification. A maximum level of identity (MLI) ≥ 98% was used for species-level and < 98% for genus-level identification. A maximum-likelihood (ML) and Bayesian-inference (BI) phylogenetic analyses of the concatenated ITS-LSU sequences were performed in order to determine the phylogenetic placement of our clinical strains. Species of the order Arachnomycetales were used as outgroup. The sequence alignments and ML / BI analyses were performed according to Valenzuela-Lopez et al. (2018). The final matrices used for the phylogenetic analysis were deposited in TreeBASE (www.treebase.org; accession number: 25068).

Antifungal susceptibility testing

In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing was carried out following the broth microdilution method from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) protocol M38 (CLSI 2017) with some modifications. The antifungal drugs tested were amphotericin B (AMB), fluconazole (FLC), voriconazole (VRC), itraconazole (ITC), posaconazole (PSC), anidulafungin (AFG), caspofungin (CFG), micafungin (MFG), terbinafine (TRB), and 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC). Briefly, incubation media, temperature and time were set to the sporulation requirements of every strain, and conidia suspensions were inoculated into the microdilution trays after being adjusted by haemocytometer counts. Incubation was set at 35 °C (without light or agitation) until the drug-free well displayed a visible fungal growth (minimum 48 h; maximum 10 days) for quantification of the Minimal Effective Concentrations (MEC) for the echinocandins and the Minimal Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) for the other tested antifungals. The MEC value was stablished as the lowest drug concentration at which short, stubby and highly branched hyphae were observed, while the MIC value was defined as the lowest concentration that completely inhibited the fungal growth. C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 was used as the quality control strain in all experiments.

RESULTS

Fungal diversity

Table 1 shows the identity of the 22 fungal strains studied. The highest number of strains corresponded to Auxarthron umbrinum (4), followed by A. alboluteum (2), A. conjugatum (2), and Malbranchea aurantiaca (2). Auxarthron zuffianum, Currahmyces indicus and M. flocciformis were represented by one strain each. Eight strains were only identified at genus-level (three belonging to Malbranchea, two to Spiromastigoides, two to Arachnomyces, and one to Arthropsis), one strain (FMR 17684) only at family-level (Onygenaceae).

Molecular phylogeny

Our phylogenetic study included 92 sequences corresponding to 75 species with a total of 1213 characters (700 ITS and 513 LSU) including gaps, of which 579 were parsimony informative (402 ITS and 177 LSU). The ML analysis was congruent with that obtained in the BI analysis, both displaying trees with similar topologies. The datasets did not show conflict with the tree topologies for the 70% reciprocal bootstrap trees, which allowed the two genes to be combined for the multi-locus analysis (Fig. 2). (single gene-based phylogenies are as supplemental material Figures S1 and S2).

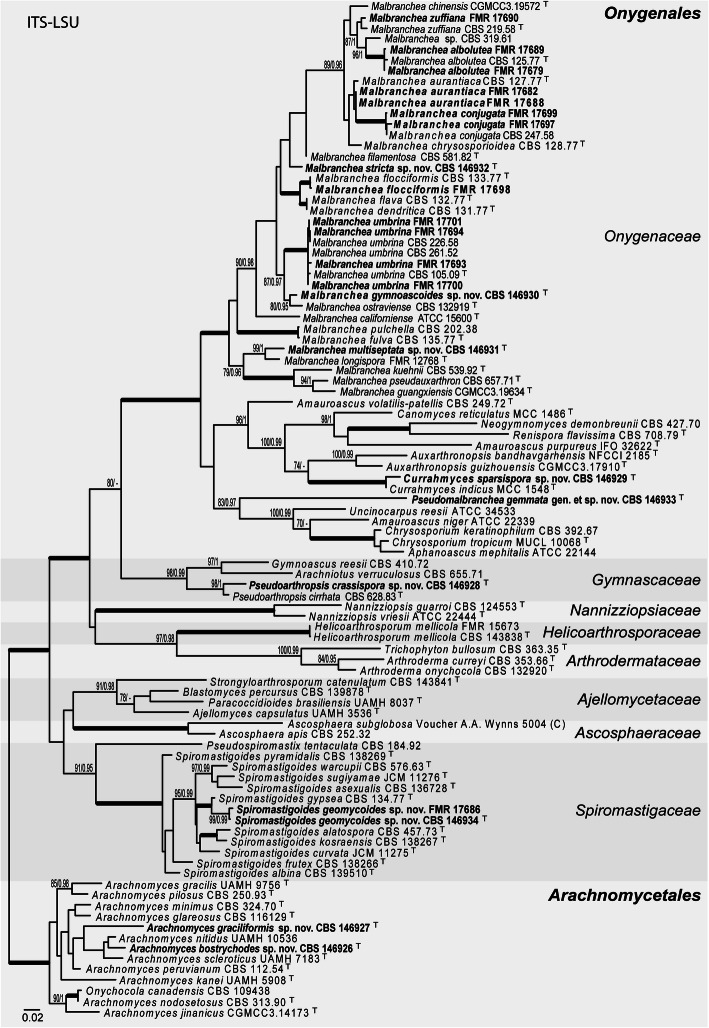

Fig. 2.

ML phylogenetic tree based on the analysis of ITS-LSU nucleotide sequences for the 22 clinical fungi from the USA. Bootstrap support values/Bayesian posterior probability scores of 70/0.95 and higher are indicated on the nodes. T = ex type. Fully supported branched (100% BS /1 PP) are indicated in bold. Strains identified by us are in bold. Arachnomyces spp. were chosen as out-group. The sequences used in this analysis are in Table 1

Twenty of our strains were placed into a main clade corresponding to the members of the Onygenales (100% BS / 1 PP), while two were placed in the Arachnomycetales (100% BS / 1 PP) (Fig. 2). The Onygenales clade was divided into eight clades corresponding to the families Onygenaceae (100% BS / 1 PP), Gymnascaceae (98% BS / 0.99 PP), Nannizziopsiaceae (100% BS / 1 PP), Helicoarthrosporaceae (100% BS / 1 PP), Arthrodermataceae (100% BS / 0.99 PP), Ajellomycetaceae (91% BS / 0.98 PP), Ascosphaeraceae (100% BS / 1 PP), and Spiromastigaceae (91% BS / 0.95 PP), which included a basal terminal branch for Pseudospiromastix tentaculata. Most of our strains (17/22) were distributed into several subclades of the Onygenaceae: 15/22 into Auxarthron/Malbranchea subclade (100% BS / 1 PP), one into a terminal branch (FMR 17683) together Currahmyces indicus (100% BS / 1 PP), and another one (FMR 17684) into a distant, independent terminal branch. One strain (FMR 17692) was placed into the Gymnascaceae, in a terminal branch together with Arthropsis cirrhata (98% BS / 1 PP). The Spiromastigaceae included the last two strains (FMR 17686 and FMR 17696 (CBS 146934)), placed into a terminal branch together Malbranchea gypsea (100% BS / 1 PP).

TAXONOMY

Arachnomyces

Since the strains FMR 17685 and FMR 17691 represented two species of Arachnomyces that were different from the other species of the genus, they are described as new, here.

Arachnomyces bostrychodes Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, sp. nov.

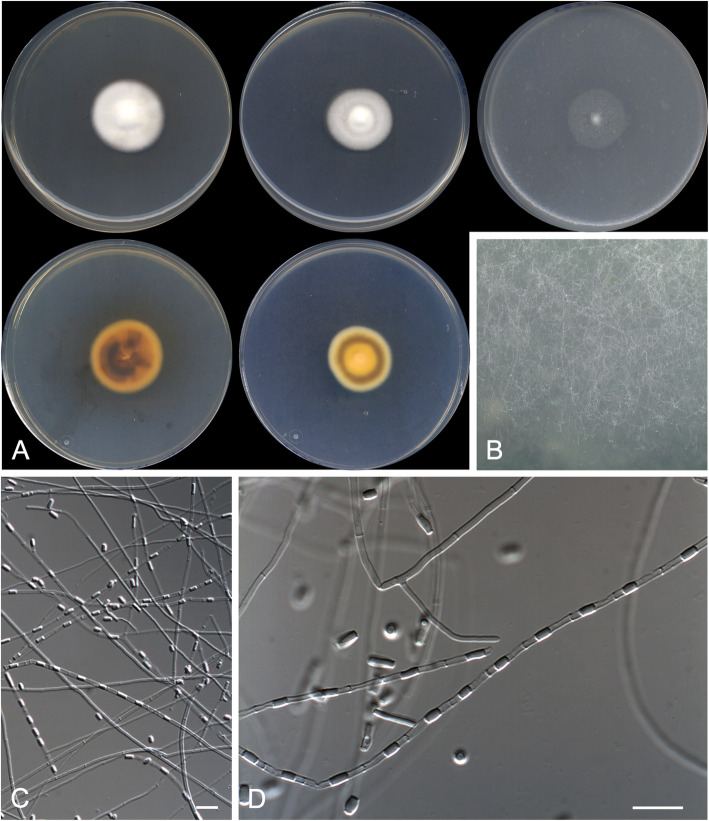

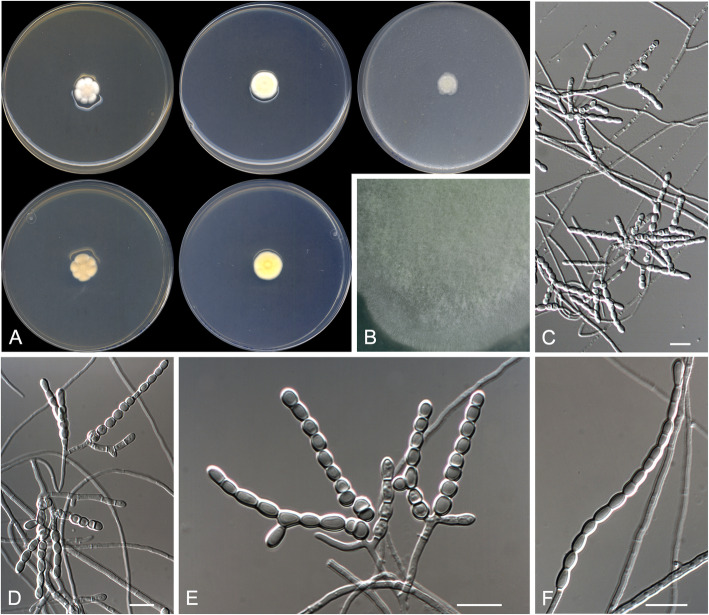

(Fig. 3)

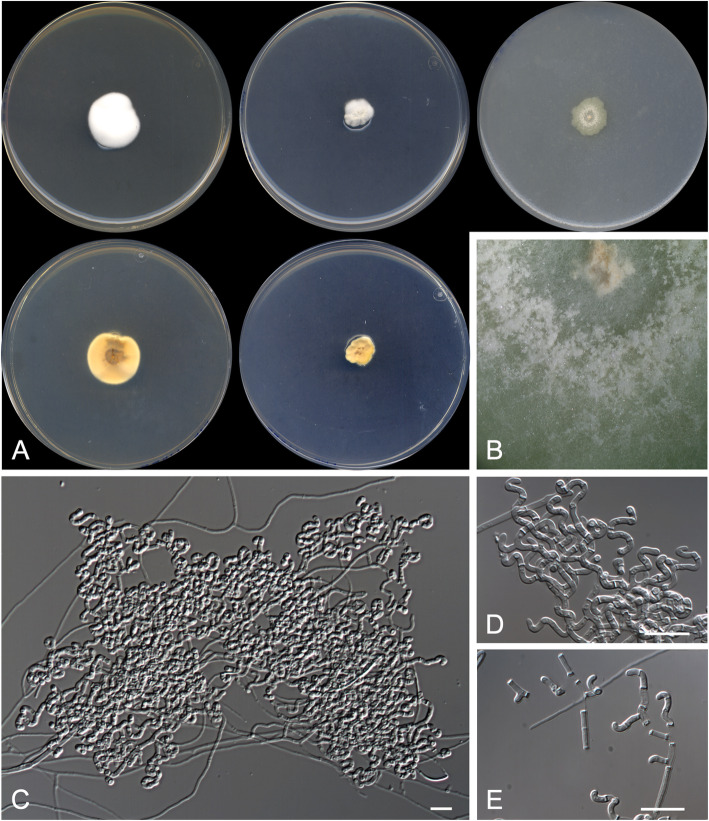

Fig. 3.

Arachnomyces bostrychodes CBS 146926 T. a Colonies on PYE, PDA and OA after 14 d at 25 °C, from left to right (top row, surface; bottom row, reverse). b Detail of the colony on OA. c, d Sinuous, contorted to coiled fertile hyphae. e Arthroconidia. Scale bar = 10 μm

MycoBank MB 834921

Etymology: From Greek βοστρυχος-, curl, due to the appearance of the reproductive hyphae.

Diagnosis: The phylogenetically closest species to Arachnomyces bostrychodes is A. peruvianum (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, A. botrychodes lacks a sexual morph and racket hyphae (both present in A. peruvianum), and produces longer conidia than A. peruvianum (4.0–8.0 × 1.0–2.0 μm vs. 4.0–5.0 × 1.0–3.0 μm); also, A. bostrychodes grows more slowly on OA (13–14 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C) than A. peruvianum (30 mm diam) (Cain 1957; Brasch et al. 2017). Arachnomyces bostrychodes morphologically resembles Arachnomyces gracilis, but the former grows faster, produces more strongly contorted branches and lacks of a sexual morph.

Type: USA: Texas: from a human scalp, 2008, N. Wiederhold (CBS H-24452 – holotype; CBS 146926 = FMR 17685 = UTHSCSA DI18-91 – ex-type cultures; LSU/ITS sequences GenBank LR701766/LR701765).

Description: Vegetative hyphae hyaline, septate, branched, smooth- and thin-walled, 1.0–2.0 μm wide. Fertile hyphae well-differentiated, arising as lateral branches from the vegetative hyphae, successively branching to form dense clusters, arcuate, sinuous, contorted or tightly curled, 1.0–2.0 μm wide, forming randomly intercalary and terminally arthroconidia. Conidia enteroarthric, hyaline, one-celled, smooth-walled, cylindrical, barrel-shaped, and finger-like-shaped when terminal, 4.0–8.0 × 1.0–2.0 μm, mostly curved and truncated at one or (mostly) both ends, separated from the fertile hyphae by rhexolysis. Chlamydospores, racquet hyphae, setae, and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PYE reaching 19–20 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, elevated, cottony, margins regular, white (5A1), sporulation absent; reverse light orange (5A4). Colonies on PDA reaching 11–12 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, elevated, velvety with floccose patches, margins regular, yellowish white (4A2), sporulation abundant; reverse greyish yellow (4B6). Colonies on PDA reaching 13–14 mm diam after 2 wk. at 30 °C, slightly elevated, velvety to floccose, regular margins, white (4A1), sporulation sparse; reverse, greyish yellow (4B6). Colonies on OA researching 13–14 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, smooth and granulose, irregular margins, yellowish white (2A2) at centre and light yellow (2A5) at edge, sporulation abundant. Exudate and diffusible pigment absent.

Minimum, optimal and maximum temperature of growth (on PDA): 10 °C, 30 °C, and 37 °C, respectively. Non-haemolytic. Casein not hydrolysed. Not inhibited by cycloheximide. Urease and esterase (TOTM) tests positive. Growth occurs at NaCl 10% w/w, but not at 20% w/w.

Arachnomyces graciliformis Rodr.-Andr., Stchigel & Cano, sp. nov.

(Fig. 4)

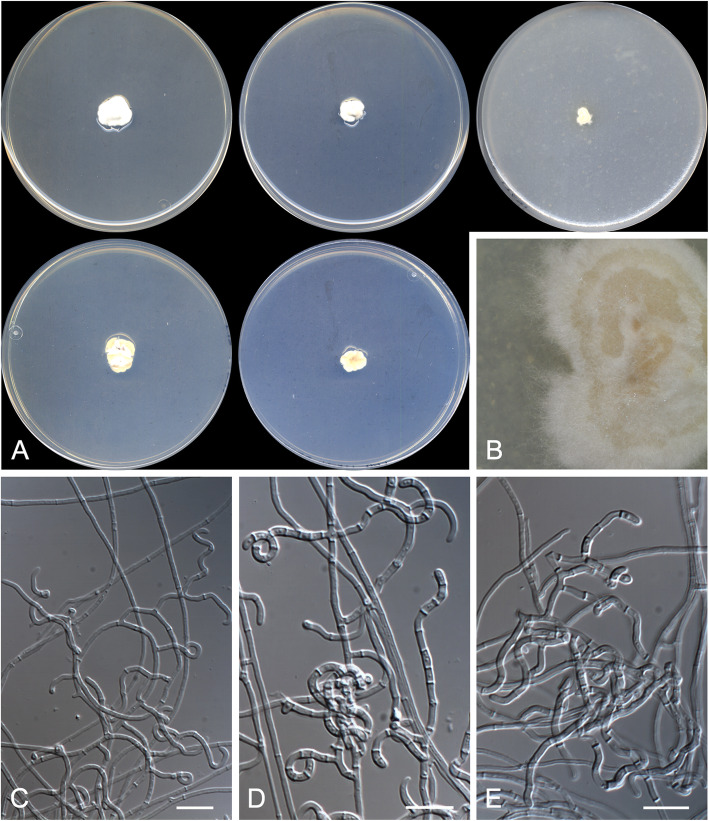

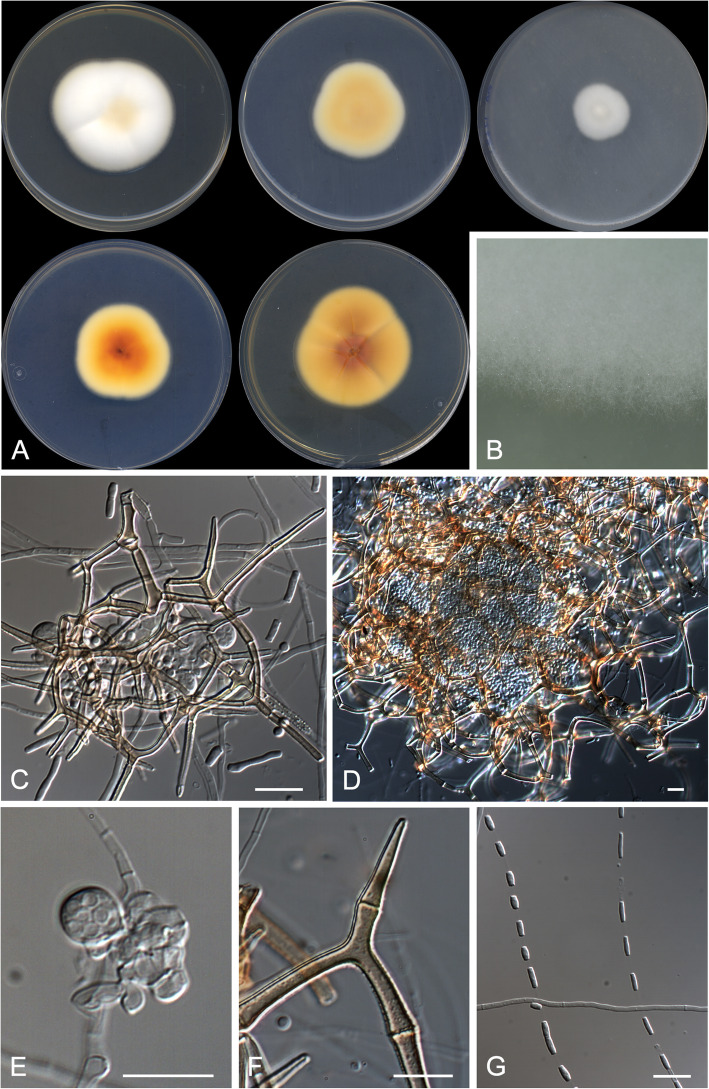

Fig. 4.

Arachnomyces graciliformis CBS 146927 T. a Colonies on PYE, PDA and OA after 14 d at 25 °C, from left to right (top row, surface; bottom row, reverse). b Detail of the colony on OA. c–e Contorted, apically coiled fertile hyphae bearing arthroconidia. Scale bar = 10 μm

MycoBank MB 834923

Etymology: Recalling the morphological similarity with Arachnomyces gracilis.

Diagnosis: Arachnomyces graciliformis is phylogenetically close to A. glareosus and to A. minimus (Fig. 2). These three species form a clade together with A. nodosetosus and A. jinanicus (84 BS / 1 PP). Unlike A. glareosus and A. minimus, A. graciliformis does not produces racquet hyphae nor sexual morph (Gibas et al. 2004) but produces longer conidia than A. glareosus (4.0–10.0 × 1.5–2.0 μm vs. 2.5–4.5 × 1.5–2.0 μm), which are not produced by A. minimus. Arachnomyces graciliformis morphologically resembles A. gracilis, but the former grows more slowly, produces more twisted fertile branches and does not form a sexual morph (Udagawa and Uchiyama 1999).

Type: USA: Massachusetts: from an animal’s bone, 2012, N. Wiederhold (CBS H-24453 – holotype; CBS 146927 = FMR 17691 = UTHSCSA DI18-97 – ex-type cultures; LSU/ITS sequences GenBank LR743668/LR743667).

Description: Vegetative hyphae hyaline, septate, branched, smooth- and thin-walled, 1.0–2.0 μm wide. Fertile hyphae well-differentiated, arising as lateral branches from the vegetative hyphae, branching repeatedly, sinuous to arcuate or apically coiled, 1.5–2.0 μm wide, forming randomly intercalary and terminally arthroconidia. Conidia enteroarthric, hyaline, unicellular, smooth- and thin-walled, cylindrical or finger-like-shaped when terminal, 4.0–10.0 × 1.5–2.0 μm, mostly curved, detached from the fertile hyphae by rhexolysis. Chlamydospores, racquet hyphae, setae, and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PYE reaching 12–13 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, elevated, velvety to floccose, margins regular, slightly furrowed, yellowish white (3A2), sporulation absent; reverse greyish orange (5B3). Colonies on PDA reaching 9–10 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety to floccose, margins regular, slightly furrowed, yellowish white (1A2), sporulation absent; reverse greyish yellow (4B3). Colonies on PDA reaching 3–4 mm diam after 2 wk. at 30 °C, slightly elevated, velvety to floccose, margins regular, slightly furrowed, yellowish white (1A2), sporulation absent; reverse, greyish yellow (4B3). Colonies on OA researching 6–7 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, velvety and granulose, margins irregular, pale yellow (4A3), sporulation absent (conidia appear after 5–6 wk. incubation). Exudate and diffusible pigment absent. Minimum, optimal and maximum temperature of growth (on PDA): 10 °C, 25 °C, and 30 °C, respectively. Non-haemolytic. Casein not hydrolysed. Not inhibited by cycloheximide. Urease and esterase tests positive. Growth occurs at NaCl 10% w/w, but not at 20% w/w.

Currahmyces

Due to the strain FMR 17683 being placed into a terminal branch of Onygenaceae together with Currahmyces indicus (Sharma and Shouche 2019), and because they differ molecularly and phenotypically, we erect the new species Currahmyces sparsispora.

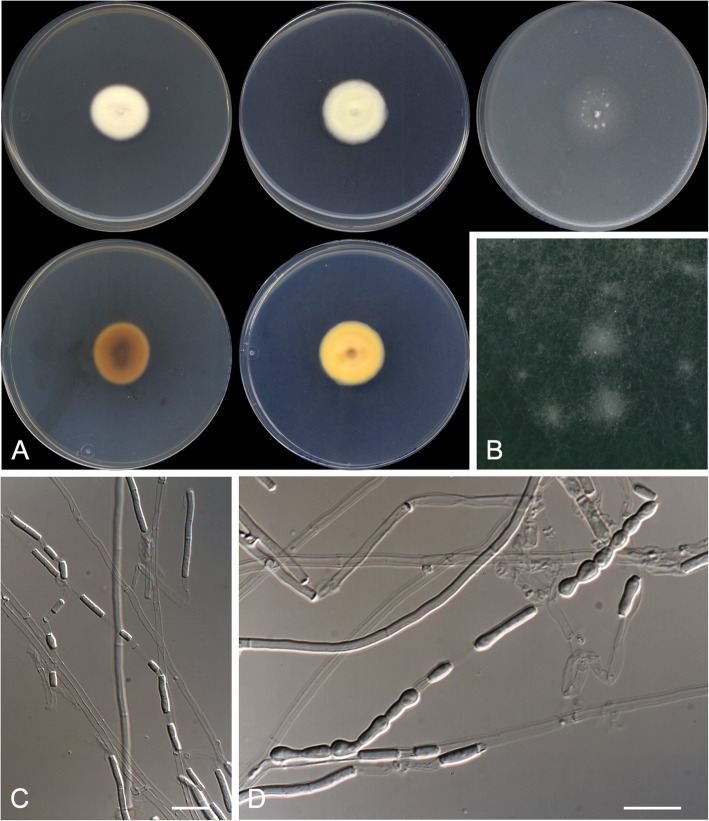

Currahmyces sparsispora Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, sp. nov.

(Fig. 5)

Fig. 5.

Currahmyces sparsispora CBS 146929 T. a Colonies on PYE, PDA and OA after 14 d at 25 °C, from left to right (top row, surface; bottom row, reverse). b Detail of the colony on OA. c–d Intercalary arthroconidia along the fertile hyphae. Scale bar = 10 μm

MycoBank MB 835692

Etymology: From Latin sparsa-, splashed, −sporarum, spore, due to the disposition of the conidia along the hyphae.

Diagnosis: Currahmyces sparsispora is phylogenetically close to C. indicus; however, they can be differentiated because the former has broader hyphae (1.5–2.0 μm vs. 0.7–1.1 μm) and lacks a sexual morph (typical gymnothecial ascomata are produced on hair-baited soil plates by C. indicus).

Type: USA: Florida: from human sputum, 2007, N. Wiederhold (CBS H-24455 – holotype; CBS 146929 = FMR 17683 = UTHSCSA DI18-89 – ex-type cultures; LSU/ITS sequences GenBank LR723273/LR723273).

Description: Vegetative hyphae septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, mostly straight, rarely branched, 1.5–2.0 μm wide. Fertile hyphae undifferentiated from the vegetative hyphae. Conidia enteroarthric, hyaline, unicellular, smooth- and thin-walled, disposed relatively far from each other along the fertile hyphae, separated by 1–2 evanescent connective cells, cylindrical to slightly barrel-shaped, 3.0–12.0 × 1.0–2.0 μm, separated by rhexolysis. Chlamydospores, racquet hyphae, setae, and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PYE reaching 27–28 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety to floccose, margins regular, pale orange (5A3) at centre and white (5A1) at edge, sporulation sparse; reverse orange (5A6). Colonies on PDA reaching 23–24 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, margins regular, light orange (5A5) at centre and orange white (5A2) at edge, sporulation sparse; reverse deep orange (6A8). Colonies on PDA reaching 30–31 mm diam after 2 wk. at 30 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, slightly furrowed, margins regular, orange (5A6), sporulation sparse; reverse brownish orange (6C8). Colonies on OA reaching 20–21 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, margins regular, orange white (5A2) at centre and white (5A1) at edge, sporulation sparse. Exudate and diffusible pigment absent in all culture media tested. Minimum, optimal and maximum temperature of growth on PDA: 10 °C, 30 °C, and 37 °C, respectively. Haemolytic. Casein not hydrolysed. Not inhibited by cycloheximide. Urease and esterase tests positive. Growth occurs at NaCl 3% w/w and 10% w/w, but not at 20% w/w.

Malbranchea

An emended description of the genus Malbranchea is provided as follows:

Malbranchea Sacc., Michelia 2(no. 8): 639 (1882).

MycoBank MB 8833.

Description: Vegetative hyphae septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, straight or branched. Asexual morph consisting in undifferentiated fertile hyphae, and/or well-differentiated lateral branches, curved or not, which form randomly or basipetally terminal and intercalary arthroconidia. Conidia enteroarthric, rarely holoarthric, unicellular, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, mostly cylindrical, barrel-shaped, or irregularly shaped, detached from the fertile hyphae by rhexolysis. Sexual morph (when present) consisting in ascomata formed by of an anastomosing network of orange to brown, ornamented or not thick-walled hyphae (gymnothecia), bearing elongate appendages and/or spine projections, within there are small, evanescent, inflated asci which forms eight globose to oblate ascospores, whose cell wall is ornamented with a (coarse or thin) reticulate pattern. Species homothallic or heterothallic, thermotolerant or thermophilic, keratinolytic, chitinolytic or cellulolytic.

Taking into account that Auxarthron and Malbranchea are congeneric, as has been shown in previous studies (Sigler et al. 2002; Sarrocco et al. 2015) and here (Fig. 2), and that Malbranchea (Saccardo 1882) has historical priority (Turland et al. 2018) over Auxarthron (Orr et al. 1963), we transfer the species of Auxarthron to Malbranchea as follows:

Malbranchea californiensis (G.F. Orr & Kuehn) Rodr.-Andr., Stchigel & Cano, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835229

Basionym: Auxarthron californiense G.F. Orr & Kuehn, Can. J. Bot. 41: 1442 (1963).

Synonym: Gymnoascus californiensis (G.F. Orr & Kuehn) Apinis, Mycol. Pap. 96: 12 (1964).

Malbranchea chinensis (Z.F. Zhang & L. Cai) Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 839604

Basionym: Auxarthron chinense Z.F. Zhang & L. Cai, Fungal Divers. 106: 55 (2020).

Malbranchea chlamydospora (M. Solé et al.) Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835230

Basionym: Auxarthron chlamydosporum M. Solé, et al., Stud. Mycol. 47: 108 (2002).

Malbranchea compacta (G.F. Orr & Plunkett) Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835231

Basionym: Auxarthron compactum G.F. Orr & Plunkett, Can. J. Bot. 41: 1453 (1963).

Malbranchea concentrica (M. Solé et al.) Rodr.-Andr., Stchigel & Cano, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835232

Basionym: Auxarthron concentricum M. Solé et al., Stud. Mycol. 47: 106 (2002).

Malbranchea conjugata (Kuehn) Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835233

Basionym: Myxotrichum conjugatum Kuehn, Mycologia 47: 883 (1956) [“1955”].

Malbranchea guangxiensis (Z.F. Zhang & L. Cai) Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 839605

Basionym: Auxarthron guangxiense Z.F. Zhang & L. Cai, Fungal Divers. 106: 57 (2020).

Synonym: Auxarthron conjugatum (Kuehn) G.F. Orr & Kuehn, Mycotaxon 24: 148 (1985).

Malbranchea longispora (Stchigel et al.) Rodr.-Andr., Stchigel & Cano, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835235

Basionym: Auxarthron longisporum Stchigel et al., Persoonia 31: 267 (2013).

Malbranchea ostraviensis (Hubka et al.) Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835236

Basionym: Auxarthron ostraviense Hubka et al., Med. Mycol. 50: 619 (2012).

Malbranchea pseudauxarthron (G.F. Orr & Kuehn) Rodr.-Andr., Stchigel & Cano, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB835237

Basionym: Auxarthron pseudauxarthron G.F. Orr & Kuehn, Mycologia 64: 67 (1972).

Malbranchea umbrina (Boud.) Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835238

Basionym: Gymnoascus umbrinus Boud., Bull. Soc. mycol. Fr. 8: 43 (1892).

Synonyms: Auxarthron brunneum (Rostr.) G.F. Orr & Kuehn, Can. J. Bot.41: 1446 (1963).

Auxarthron umbrinum (Boud.) G.F. Orr & Plunkett, Can. J. Bot. 41: 1449 (1963).

Auxarthron thaxteri (Kuehn) G.F. Orr & Kuehn, Mycologia 63: 200 (1971).

Gymnoascus subumbrinus A.L. Sm. & Ramsb., Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 5: 424 (1917) [“1916”].

Gymnoascus umbrinus var. thaxteri (Kuehn) Apinis, Mycol. Pap. 96: 14 (1964).

Myxotrichum brunneum Rostr., Bot. Tidsskr. 19: 216 (1895).

Myxotrichum thaxteri Kuehn, Mycologia 47: 878 (1956) [“1955”].

Malbranchea zuffiana (Morini) Rodr.-Andr., Stchigel & Cano, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835239

Basionym: Gymnoascus zuffianus Morini, Mem. R. Accad. Sci. Ist. Bologna, ser. 4 10: 205 (1889).

Synonym: Auxarthron zuffianum (Morini) G.F. Orr & Kuehn, Can. J. Bot. 41: 1445 (1963).

We also update the Malbranchea species names listed below:

Malbranchea albolutea Sigler & J.W. Carmich., Mycotaxon 4: 416 (1976).

Synonym: Auxarthron alboluteum Sigler et al., Stud. Mycol. 47: 118 (2002).

Malbranchea filamentosa Sigler & J.W. Carmich., Mycotaxon 15: 468 (1982).

Synonym: Auxarthron filamentosum Sigler et al., Stud. Mycol. 47: 116 (2002).

Because in a BLAST search using the ITS and LSU nucleotide sequences from the ex-type strains, Malbranchea circinata and M. flavorosea match with taxa in the family Myxotrichaceae, both those species are excluded to the genus.

After examination of the lectotype of Auxarthron indicum (Patil and Pawar 1987, as “indica”), we concluded that this fungus must be excluded from Malbranchea because its sexual morph differs mainly from all species described for the former genus. Whereas Auxarthron indicum produces smooth-walled ellipsoidal ascospores and gymnothecial ascomata lacking of true appendages, in Malbranchea spp. the ascospores are globose and mostly ornamented, and the ascomata have appendages. Based on the fact that there is no type strain of this species available we consider it as of uncertain application.

Despite the strain FMR 17681 being placed phylogenetically close to Malbranchea ostraviense and M. umbrina, it differs genetically and phenotypically from both species, therefore we describe the new species Malbranchea gymnoascoides as follows:

Malbranchea gymnoascoides Rodr.-Andr., Stchigel & Cano, sp. nov.

(Fig. 6)

Fig. 6.

Malbranchea gymnoascoides CBS 146930 T. a Colonies on PYE, PDA and OA after 14 d at 25 °C, from left to right (top row, surface; bottom row, reverse). b Detail of the colony on OA. c–d Young and mature ascomata. e Young ascus on fertile hyphae. f Peridial spine-like appendage. g Intercalary arthroconidia along the fertile hyphae. Scale bar = 10 μm

MycoBank MB 835212

Etymology: As the ascomata are morphologically like those of Gymnoascus reessii.

Diagnosis: Malbranchea gymnoascoides is phylogenetically close to M. ostraviensis and M. umbrina (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, M. gymnoascoides produces smaller ascomata (to 250 μm diam in M. gymnoascoides vs. to 450 and to 600 μm diam in both, M. ostraviensis and M. umbrina, respectively) (Orr et al. 1963; Hubka et al. 2013). Also, the peridial appendages of M. gymnoascoides are longer than those of M. umbrina (250–400 μm vs. 5–72 μm), but shorter than those of M. ostraviensis (350–600 μm long). The ascospores of M. gymnoascoides are like those of M. ostraviensis (smooth-walled under the bright field microscope, oblate to globose, 2.5–3.5 μm diam), whereas those of M. umbrina are lenticular and measure 2.8–4.0 × 2.1–2.6 μm. Moreover, the arthroconidia of M. gymnoascoides are larger than those of M. umbrina (6.0–10.0 × 1.5–2.0 μm and 2.6–7.0 × 1.4 μm, respectively). Malbranchea ostraviensis also produces a pinkish to red diffusible pigment on MEA, PDA and SDA, a feature not observed in M. gymnoascoides nor in M. umbrina. Both Malbranchea gymnoascoides as well as of M. umbrina can grow slowly at 35 °C, whereas the maximum temperature of growth for M. ostraviensis is of 32 °C.

Type: USA: Texas: from human bronchial washing specimen, 2005, N. Wiederhold (CBS H-24456 – holotype; CBS 146930 = FMR 17681 = UTHSCSA DI18-87 – ex-type cultures; LSU/ITS sequences GenBank LR701758/LR701757).

Description: Vegetative hyphae septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, mostly straight, rarely branched, 1.5–2.5 μm wide. Asexual morph consisting in undifferentiated fertile hyphae which form randomly intercalary and terminally arthroconidia. Conidia enteroarthric, unicellular, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, mostly barrel-shaped, sometimes cylindrical or irregularly-shaped, 6.0–10.0 × 1.5–2.0 μm, detached by rhexolysis. Ascomata gymnothecial, solitary or in clusters, hyaline at first, becoming orange brown with the age, globose or nearly so, 130–250 μm diam excluding the appendages, which cover entirely the surface. Peridial hyphae septate, orange brown, branching and anastomosing to form a reticulate network, asperulate, very thick-walled, 3.5–5.5 μm wide, fragmenting by the septa when ageing, with lateral appendages. Appendages 0–1-septate, orange brown, asperulate, thick-walled, progressively tapering towards the apex, apex sinuous, 250–400 μm long, connected by basal knuckle joints. Asci 8-spored, globose or nearly so, 4–7 μm diam, soon deliquescent. Ascospores unicellular, hyaline at first, yellowish in mass when mature, smooth-walled under bright field microscope, globose, 2.5–3.5 μm diam.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PYE reaching 46–47 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety to floccose, margins regular, pale orange (5A3) at centre and white (5A1) at edge, sporulation sparse; reverse orange (5A6). Colonies on PDA reaching 36–37 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, margins regular, light orange (5A5) at centre and orange white (5A2) at edge, sporulation sparse; reverse deep orange (6A8). Colonies on PDA reaching 31–32 mm diam after 2 wk. at 30 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, margins regular, slightly furrowed, orange (5A6), sporulation sparse; reverse brownish orange (6C8). Colonies on OA reaching 21–22 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, margins regular, orange white (5A2) at centre and white (5A1) at edge, sporulation sparse. Exudate and diffusible pigment absent in all culture media tested. Minimum, optimal and maximum temperature of growth on PDA: 10 °C, 25 °C, and 35 °C, respectively. Non-haemolytic. Casein hydrolysed without pH change. Not inhibited by cycloheximide. Urease and esterase tests positive. Growth occurs at NaCl 10% w/w, but not at 20% w/w.

Despite the strain FMR 17695 being phylogenetically close to Malbranchea longispora, it differs phylogenetically and morphologically from it. Consequently, we describe the new species Malbranchea multiseptata.

Malbranchea multiseptata Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, sp. nov.

(Fig. 7)

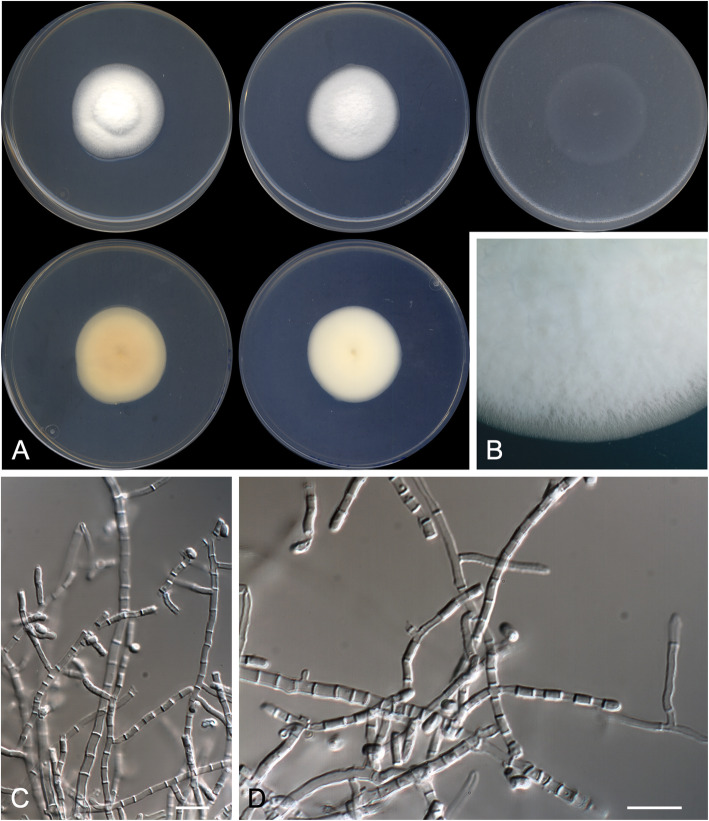

Fig. 7.

Malbranchea multiseptata CBS 146931 T. a Colonies on PYE, PDA and OA after 14 d at 25 °C, from left to right (top row, surface; bottom row, reverse). b Detail of the colony on PDA. c–d Highly septate fertile hyphae and arthroconidia. Scale bar = 10 μm

MycoBank MB 835213

Etymology: From Latin multi-, many, and –septatae, septa, because the vegetative hyphae are multiseptate.

Diagnosis: Malbranchea multiseptata is phylogenetically linked to M. longispora. Nevertheless, M. multiseptata does not form chlamydospores nor a sexual morph as in M. longispora (Crous et al. 2013). Also, M. multiseptata produces shorter conidia (3.0–9.0 × 1.5–2.0 μm) than those of M. longispora (4.0–24.0 × 1.0–5.5 μm).

Type: USA: Texas: from human bronchial washing specimen, 2014, N. Wiederhold (CBS H-24457 – holotype; CBS 146931 = FMR 17695 = UTHSCSA DI18-101 – ex-type cultures; LSU/ITS sequences GenBank LR701760/LR701759).

Description: Vegetative hyphae hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled straight to sinuous, sparsely branched, 1.0–2.0 μm wide, becoming highly septate with the age, septa thickened. Fertile hyphae arising as lateral branches (sometimes opposite each other) from the vegetative hyphae, unbranched, straight or slightly sinuous, 1.5–2.0 μm wide, forming randomly intercalary and terminally arthroconidia. Conidia enteroarthric, unicellular, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, separated by evanescent connective cells, cylindrical, 3.0–9.0 × 1.5–2.0 μm, rounded at the end when terminal, rhexolytic secession. Chlamydospores, racquet hyphae, setae, and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PYE reaching 35–36 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, elevated, velvety to floccose, margins regular, white (5A1), sporulation sparse; reverse greyish yellow (4B4). Colonies on PDA reaching 34–35 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety to floccose, margins regular, white (5A1), sporulation absent; reverse yellowish white (3A2). Colonies on PDA reaching 27–28 mm diam after 2 wk. at 30 °C, slightly elevated, velvety to floccose, margins regular, white (5A1), sporulation absent; reverse pale yellow (3A3). Colonies on OA researching 37–38 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, barely perceptible growth, not distinguishable colour, sporulation sparse. Exudate and diffusible pigment absent in all culture media tested. Minimum, optimal and maximum temperature of growth on PDA: 10 °C, 25 °C, and 35 °C, respectively. Haemolytic. Casein hydrolyzed without pH change. Not inhibited by cycloheximide. Urease positive. Growth occurs at NaCl 3% w/w, but not at 10%w/w. Neither grow on TOTM.

Because the strain FMR 17680 was placed phylogenetically close to Malbranchea filamentosa but in a separate terminal branch, and because both differ morphologically and genotypically, the new species Malbranchea stricta is also described.

Malbranchea stricta Rodr.-Andr., Stchigel & Cano, sp. nov.

(Fig. 8)

Fig. 8.

Malbranchea stricta CBS 146932 T. a Colonies on PYE, PDA and OA after 14 d at 25 °C, from left to right (top row, surface; bottom row, reverse). b Detail of the colony on OA. c–e Alternate arthroconidia on primary hyphae and lateral branches. Scale bar = 10 μm

MycoBank MB 835219

Etymology: Latin stricta, strict, due to the production of the typical reproductive structures of the genus.

Diagnosis: Malbranchea stricta is phylogenetically close to M. filamentosa. Also, both species lack a sexual morph (Sigler et al. 2002). However, M. filamentosa produces more regularly shaped conidia than M. stricta, and forms thick-walled brown setae, structures absent in M. stricta.

Type: USA: Florida: human nail, 2003, N. Wiederhold (CBS H-24458 – holotype; CBS 146932 = FMR 17680 = UTHSCSA DI18-86 – ex-type cultures; LSU/ITS sequences GenBank LR701639/LR701638).

Description: Vegetative hyphae hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, straight to sinuous, sparsely branched, 1.5–2.0 μm wide. Fertile hyphae well-developed, arising as lateral branches from the vegetative hyphae, mostly unbranched, right or slightly sinuous, contorted or arcuate at the end, up to 25 μm long, 1.5–2.0 μm wide, or developing at the extremes of the vegetative hyphae, in both cases forming arthroconidia randomly intercalary and terminally. Arthroconidia enteroarthric, hyaline, becoming yellowish with the age, barrel-shaped, “T”-shaped, “Y”-shaped, finger-shaped or irregularly-shaped, 2.0–6.0 × 1.0–2.0 μm, with rhexolytic secession. Chlamydospores, racquet hyphae, and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PYE reaching 32–33 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, velvety, regular margins, furrowed, white (4A1), sporulation sparse; reverse pale orange (5A3). Colonies on PDA reaching 20–21 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety to floccose, regular margins, white (3A1), sporulation abundant; reverse pale yellow (4A3). Colonies on PDA reaching 20–21 mm diam after 2 wk. at 30 °C, slightly elevated, velvety to floccose, margins regular, white (3A1), sporulation abundant; reverse yellowish brown (5E8) at centre and greyish yellow (4B5) at the margins. Colonies on OA researching 16–17 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, granulose, white (3A1), margins regular, sporulation sparse. Exudate and diffusible pigment absent. Minimum, optimum and maximum temperature of growth on PDA: 10 °C, 30 °C, and 37 °C, respectively. Colonies haemolytic (on BA), and casein hydrolyzed without pH changes at 25 °C (on BCP-MS-G). Not inhibited by cycloheximide. Urease and esterase tests positive. Growth occurs at NaCl 10% w/w, but not at 20% w/w.

Pseudoarthropsis

Since the strain FMR 17692 was placed in the same terminal clade as Arthropsis cirrhata, while the type species of the genus (Arthropsis truncata) is phylogenetically distant (in Sordariales; Giraldo et al. 2013), we erect the new genus Pseudoarthropsis for A. cirrhata, and the new species Pseudoarthropsis crassispora.

Pseudoarthropsis Stchigel, Rodr.-Andr. & Cano, gen. nov.

MycoBank MB 834925

Etymology: From Greek ψευδής-, resembling, because the morphological semblance to Arthropsis.

Diagnosis: Mycelium composed by hyaline to orange, septate hyphae. Conidiophores consisting of fertile lateral branches and a portion of the main subtending hypha, with all these structures disintegrating into yellowish orange, thin-walled, cylindrical to cuboid enteroarthric conidia, or into hyaline, thick-walled, ellipsoidal, globose to barrel-shaped holoarthric conidia.

Type species: Pseudoarthropsis cirrhata (Oorschot & de Hoog) Stchigel, Rodr.-Andr. & Cano 2021.

Pseudoarthropsis cirrhata (Oorschot & de Hoog) Stchigel, Rodr.-Andr. & Cano, comb. nov. MycoBank MB 834928

Basionym: Arthropsis cirrhata Oorschot & de Hoog, Mycotaxon 20: 130 (1984).

Description: Vegetative hyphae septate, pale yellowish orange, smooth- and thin-walled, dichotomously branched, 2–3 μm wide. Fertile hyphae well differentiated, arising at right angles as recurved lateral branches of the vegetative hyphae, forming septa basipetally to produce chains of enteroarthric conidia. Arthroconidia yellowish orange, smooth- and thin-walled, cylindrical to cuboid, often broader than long, 2.5–4.0 × 2–3 μm, truncated at both ends, separated by trapezoid connectives, secession rhexolytic. Colonies on PYE reaching 4–5 mm diam after 10 d at 25 °C, powdery, fealty, slightly raised, orange (5A7), pale orange (5A5) at centre; reverse brownish orange (7C8), diffusible pigment brown.

Type: The Netherlands: from a wall near Schiphol, 1984, C.A.N. van Oorschot (CBS 628.83).

Pseudoarthropsis crassispora Rodr.-Andr., Stchigel & Cano, sp. nov.

(Fig. 9)

Fig. 9.

Pseudoarthropsis crassispora CBS 146928 T. a Colonies on PYE, PDA and OA after 14 d at 25 °C, from left to right (top row, surface; bottom row, reverse). b Detail of the colony on OA. c–e Bi- to trichotomously-branched fertile hyphae. f A large chain of holoarthric conidia. Scale bar = 10 μm

MycoBank MB 834930

Etymology: From Latin crassus-, thick, and -sporarum, spore, because of the thick wall of the conidia.

Diagnosis: Pseudoarthropsis crassispora is phylogenetically close to P. cirrhata. Nevertheless, the former produces holoarthric conidia, while they are enteroarthric in the latter. Also, the conidia of P. crassispora are ellipsoidal, globose or broadly barrel-shaped, while these are cylindrical to cuboid (often wider than they are long) in P. cirrhata (van Oorschot and de Hoog 1984). Moreover, the conidia are bigger in P. crassispora than in P. cirrhata (4.5–5.5 × 2.5–3.5 μm vs. 2.5–4.0 × 2.0–3.0 μm). Also, P. crassispora grows faster than P. cirrhata (on PYE at 25 °C), and the maximum temperature of growth is at 37 °C and 30 °C, respectively.

Type: USA: Minnesota: from a human bronchial washing specimen, 2012, N. Wiederhold (CBS H-24454 – holotype; CBS 146928 = FMR 17692 = UTHSCSA DI18-98 – ex-type cultures; LSU/ITS sequences GenBank LR701763/LR701764).

Description: Vegetative hyphae septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, mostly straight, occasionally branched, 1.5–2.0 μm wide. Fertile hyphae well-differentiated, arising as lateral branches of the vegetative hyphae, hyaline, septate, smooth- and thin-walled, erect, simple or branched up to 3 times at the apex, stipe 10–20 × 1.5–2.0 μm, branches 10–70 × 1.5–2.0 μm, forming septa basipetally to produce chains of arthroconidia. Conidia holoarthric, unicellular, hyaline, smooth- and thick-walled, ellipsoidal, globose or barrel-shaped, transiently presents as bi-cellular conidia, 2.5–3.5 × 4.5–5.5 μm, in chains of up to 20, separate from the fertile hyphae by schizolysis, rarely by rhexolysis. Chlamydospores, racquet hyphae, setae, and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PYE reaching 13–14 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, margins regular, furrowed, yellowish white (3A2) and yellowish grey (4B2) at centre, sporulation abundant; reverse pale yellow (4A3. Colonies on PDA reaching 14–15 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, velvety, margins regular, greenish white (30A2) and pastel green (30A4) at centre, sporulation abundant; reverse pastel yellow (3A4). Colonies on PDA reaching 15–16 mm diam after 2 wk. at 30 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, margins regular, furrowed, yellowish white (3A2), sporulation sparse; reverse yellow (3A6), with a scarce production of yellowish diffusible pigment. Colonies on OA researching 10–11 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, velvety to floccose, margins irregular, greenish white (30A2) and pale green (28A3) at centre, sporulation abundant. Exudate and diffusible pigment absent, except on PDA. Minimum, optimal and maximum temperature of growth on PDA: 10 °C, 30 °C, and 37 °C, respectively. Non-haemolytic. Casein hydrolyzed without pH change. Not inhibited by cycloheximide. Urease and esterase tests positive. The fungus grows up to NaCl 10% w/w, but not at 20% w/w.

Pseudomalbranchea

Despite the strain FMR 17684 being placed phylogenetically in Onygenaceae, it is paraphyletic described as the type species of the new genus Pseudomalbranchea.

Pseudomalbranchea Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, gen. nov.

MycoBank MB 835220

Etymology: Recalling the morphological similarity with Malbranchea.

Diagnosis: Arthroconidia one-celled, intercalary disposed along unbranched vegetative hyphae, mostly enteroarthric, occasionally holoarthric, cylindrical but becoming globose with the age.

Type species: Pseudomalbranchea gemmata Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel 2021

Description: Mycelium sparse, composed of hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled septate hyphae. Asexual morph consisting of mostly enteroarthric, occasionally holoarthric, conidia, intercalary disposed along unbranched vegetative hyphae, solitary or in short chains, with rhexolytic or rarely schizolytic secession. Arthroconidia one-celled, hyaline, smooth- and thick-walled, cylindrical but becoming globose with the age. Chlamydospores, racquet hyphae and sexual morph not observed.

Pseudomalbranchea gemmata Rodr.-Andr., Cano & Stchigel, sp. nov.

(Fig. 10)

Fig. 10.

Pseudomalbranchea gemmata CBS 146933 T. a Colonies on PYE, PDA and OA after 14 d at 25 °C, from left to right (top row, surface; bottom row, reverse). b Detail of the colony on OA. c–d Large, intercalary, irregularly-shaped arthroconidia disposed singly or in chains along the fertile hyphae. Scale bar = 10 μm

MycoBank MB 835221

Etymology: From the Latin gemmatum, jewelled, because the swollen conidia disposed in chains.

Diagnosis: Pseudomalbranchea gemmata is phylogenetically close to Uncinocarpus reesii and Amauroascus volatilis-patellis. However, it does not produce a sexual morph and it differs from U. reessi and A. volatilis-patellis by the production of longer arthroconidia (4.0–11.0 × 2.0–3.5 μm in P. gemmata vs. 3.5–6.0 × 2.5–3 μm in U. reessi, and 4.0–5.4 × 2.0–3.0 in A. volatilis-patellis; Orr and Kuehn 1972, Sigler and Carmichael 1976, Currah 1985). As well as A. volatilis-patellis, P. gemmata lacks appendages, which are present and similar to the asexual morph in U. reessi (Currah 1985).

Type: USA: Florida: from human bronchial washing specimen, 2014, N. Wiederhold (CBS H-24459 – holotype, CBS 146933 = FMR 17684 = UTHSCSA DI18-90 – ex-type cultures; LSU/ITS sequences GenBank LR701762/LR701761).

Description: Mycelium sparse, composed of hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, sparsely septate hyphae, 1.0–2.0 μm wide. Conidia enteroarthric (occasionally holoarthric), intercalary disposed along unbranched vegetative hyphae, one-celled, solitary or in short chains of up to 7, one-celled, hyaline, smooth- and thick-walled, cylindrical but becoming globose with the age, 4.0–11.0 × 2.0–3.5 μm, liberated from the fertile hyphae by rhexolysis (rarely by schizolysis). Chlamydospores, racquet hyphae and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PYE reaching 22–23 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, margins regular, pale yellow (3A3), sporulation sparse; reverse brown (6E6). Colonies on PDA reaching 24–25 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, slightly elevated, velvety, margins regular, pale yellow (3A3), sporulation sparse; reverse light yellow (4A5). Colonies on PDA reaching 25–26 mm diam after 2 wk. at 30 °C, flattened, radially folded, velvety, margins regular, pale yellow (3A3), sporulation sparse; reverse light yellow (4A5). Colonies on OA reaching 28–29 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, velvety to granulose, irregular margins, white (6A1), sporulation sparse. Exudate and diffusible pigment lacking. Minimum, optimum and maximum temperature of growth on PDA: 10 °C, 30 °C, and 37 °C, respectively. Colonies haemolytic, casein not hydrolyzed. The fungus was not inhibited by cycloheximide. Urease and esterase tests positive. Growth occurs at NaCl 3% w/w, but not higher concentration.

Spiromastigoides

Because strains FMR 17686 and FMR 17696 were placed together in a terminal branch close to the ex-type strain of M. gypsea in the Spiromastigaceae clade (Fig. 2), M. gypsea is combined into Spiromastigoides and these two strains are described as the new species S. geomycoides.

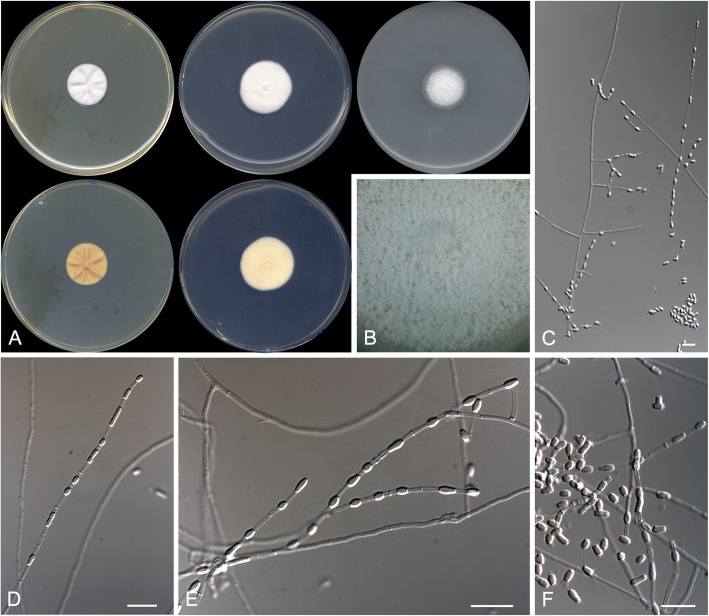

Spiromastigoides geomycoides Stchigel, Rodr.-Andr. & Cano, sp. nov.

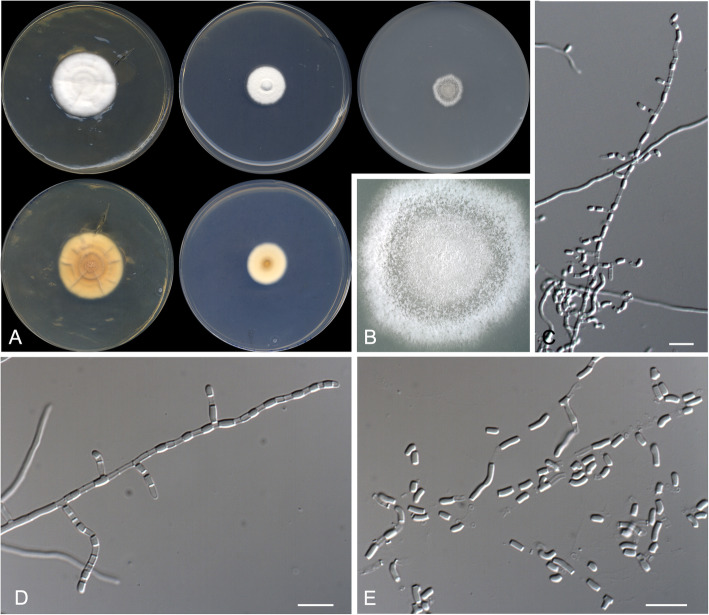

(Fig. 11)

Fig. 11.

Spiromastigoides geomycoides CBS 146934 T. a Colonies on PYE, PDA and OA after 14 d at 25 °C, from left to right (top row, surface; bottom row, reverse). b Detail of the colony on OA. c Fertile lateral branches mimicking Geomyces spp. conidiophores. d–e Fertile hyphae with intercalary, barrel-shaped arthroconidia. f Morphological diversity of arthroconidia. Scale bar = 10 μm

MycoBank MB 835222

Etymology: From the production of conidiophores morphologically similar to those of the genus Geomyces.

Diagnosis: Spiromastigoides geomycoides is phylogenetically close to S. gypsea. However, it produces smaller conidia (1.5–2.5 × 1.0–2.0 μm) than S. gypsea [(2.5)3–6(9) × 2–2.5 μm; Sigler and Carmichael 1976]. Also, S. geomycoides grows faster than S. gypsea on PYE at 35 °C.

Type:USA: Illinois: from a human foot skin, 2014, N. Wiederhold (CBS H-24460 – holotype, CBS 146934 = FMR 17696 = UTHSCSA DI18-102 – ex-type cultures; LSU/ITS sequences GenBank LR701768/LR701768).

Description: Mycelium abundant, composed of hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, septate, branched, 1.0–2.0 μm wide hyphae, septa thickened with age. Fertile hyphae arising as lateral branches, straight or slightly curved, unbranched or, rarely, with a branching pattern similar to that of the conidiophores of Geomyces, septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, producing intercalary and terminally arthroconidia separated by 1–2 empty intermediary cells. Conidia enteroarthic, unicellular, hyaline, mostly barrel-shaped, less frequently “T”-shaped or cylindrical, 1.5–2.5 × 1.0–2.0 μm, rhexolytic dehiscence. Chlamydospores, racquet hyphae and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PYE reaching 24–25 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, velvety, furrowed, regular margins, white (4A1), abundant sporulation; reverse, pale orange (5A3). Colonies on PDA reaching 26–27 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, velvety, regular margins, white (4A1), abundant sporulation; reverse, yellowish white (4A2). Colonies on PDA reaching more than 90 mm diam after 2 wk. at 30 °C, flattened, velvety, regular margins, yellowish white (4A2), sporulation absent; reverse, pale yellow (4A3). Colonies on OA researching 20–21 mm diam after 2 wk. at 25 °C, flattened, granulose, regular margins, white (4A1), abundant sporulation. Exudate and diffusible pigment absent in all culture media tested. Minimum, optimum and maximum temperature of growth on PDA: 5 °C, 30 °C, and 37 °C, respectively. Colonies non-haemolytic. Casein not hydrolyzed. Resistant to cycloheximide. Urease negative and esterase positive. Growth occurs at NaCl 10% w/w, but not at 20% w/w.

Other specimen examined: USA: Minnesota: from blood, 2009, N. Wiederhold (FMR 17686).

Spiromastigoides gypsea (Sigler & Carmichael) Stchigel, Rodr.-Andr. & Cano, comb. nov.

MycoBank MB 835228

Basionym: Malbranchea gypsea Sigler & Carmichael, Mycotaxon 4: 455 (1976).

Description (adapted from the original description): Arthroconidia produced intercalary or terminally along straight primary hyphae, or on short or long lateral branches, separated each one by one or more alternate empty cells, or, rarely, formed immediately adjacent to each other. Arthroconidia unicellular, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, cylindrical or slightly barrel-shaped, (2.5) 3–6 (9) × 2–2.5 μm, slightly broader than the interconnecting cells. No sexual morph obtained by matting. Colonies on PYE reaching 17–39 mm after three wk. at room temperature, chalky white to creamy white, downy to velvety, slightly raised, surface folded to convoluted, umbonated at centre, reverse buff. Optimum temperature of growth 25–30 °C. Maximum temperature of growth 37 °C (but strain depending).

KEYS

Key to Arachnomyces species

Adapted from Sun et al. (2019).

1 Homothallic; asexual morph present or not.................................................................................................................................. 2

Heterothallic; asexual morph present ................................................................................................................................................. 6

2(1) Peridial setae coiled or circinate; asexual morph absent....................................................................................................... 3

Peridial setae straight, tapering towards the apex; asexual morph arthroconidia ……………................................. gracilis

3(2) Peridial setae slightly nodose; ascospores mostly < 3.5 μm diam ………………….…...................................................... 4

Peridial setae smooth-walled; ascospores mostly > 3.5 μm diam................................................................................................. 5

4(3) Ascospores smooth-walled............................................................................................................................................. minimus

Ascospores echinulate.......................................................................................................................................................... peruvianus

5(3) Ascomata 100–300 μm diam............................................................................................................................................. nitidus

Ascomata 500–700 μm diam.............................................................................................................................................. sulphureus

6(1) Arthroconidia alternate................................................................................................................................................................... 7

Arthroconidia in persistent chains..................................................................................................................................................... 12

7(6) Arthroconidia cylindrical or barrel-shaped; sclerotia present............................................................................................. 8

Arthroconidia distinct; sclerotia absent.............................................................................................................................................. 9

8(7) Colonies becoming greyish brown, not growing at 35 °C..................................................................................... glareosus

Colonies white to pale brown, growing at 35 °C........................................................................................................... scleroticus

9(7) Arthroconidia subglobose to pyriform..................................................................................................................................... 10

Arthroconidia cylindrical to finger-like-shaped.............................................................................................................................. 11

10(9) Arthroconidia smooth-walled to finely asperulate; setae (produced on the vegetative mycelium) smooth-walled to slightly nodose............................................................................................................................... kanei

Mature arthroconidia coarsely verrucose; setae (produced on the vegetative mycelium) strongly nodose............................................................................................................................................................. pilosus

11(9) Fertile hyphae successively branching to form dense clusters, arcuate, sinuous, contorted or tightly curled................................................................................................................ bostrychodes

Fertile hyphae branching but not in clusters; branches only apically coiled.......................................................................... graciliformis

12(6) Setae (produced on the vegetative mycelium) strongly nodose, circinate or loosely coiled at the apex................................................................................................................................................ nodosetosus

Setae (produced on the vegetative mycelium) strongly nodose, tip straight................................................................... jinanicus

Key to Malbranchea species

Adapted from Sigler and Carmichael (1976), Solé et al. (2002), and Hubka et al. (2013).

1 Homothallic species.............................................................................................................................................................................. 2

Heterothallic species............................................................................................................................................................................... 13

2(1) Peridial appendages longer than 150 μm long.......................................................................................................................... 3

Peridial appendages shorter or absent................................................................................................................................................. 8

3(2) Appendages 350–600 μm in length; diffusible pigment pinkish to reddish; not growing at 35 °C …............ ostraviensis

Above features not combined................................................................................................................................................................ 4

4(3) Ascospores smooth-walled under bright field microscope....................................................................... gymnoascoides

Ascospores reticulate................................................................................................................................................................................ 5

5(4) Peridial cells short, 4–12 μm in length; peridial projections with truncate ends.......................................... compacta

Peridial cells longer; peridial projections with mostly acute ends............................................................................................... 6

6(5) Ascospores usually exceeding 4 μm diam......................................................................................................... californiensis

Ascospores ≤4 μm diam........................................................................................................................................................................... 7

7(6) Species growing at 37 °C................................................................................................................................................ conjugata

No growth at 37 °C..................................................................................................................................................................... umbrina

8(2) Asexual morph not produced......................................................................................... guangxiensis / pseudauxarthron

Malbranchea-like asexual morph present........................................................................................................................................... 9

9(8) Ascomata with spine-like peridial projections, 27–40 μm in length.................................................................... zuffiana

Ascomata without peridial projections............................................................................................................................................. 10

10(9) Colonies on PDA brown................................................................................................................................................. kuehnii

Colonies on PDA otherwise................................................................................................................................................................. 11

11(10) Peridial hyphae smooth-walled........................................................................................................................... concentrica

Peridial hyphae strongly ornamented; chlamydospores present ….......................................................................................... 12

12(11) Arthroconidia 2–10 × 2.5–3.5 μm; growing above 30 °C …................................................................. chlamydospora

Arthroconidia 4–24 × 1.0–5.5 μm; not growing above 30 °C..................................................................................... longispora

13(1) Fertile hyphae arcuate or curved............................................................................................................................................. 14

Fertile hyphae straight to sinuous, branched or not..................................................................................................................... 21

14(13) Fertile hyphae coiled................................................................................................................................................................. 15

Fertile hyphae curved or arcuate........................................................................................................................................................ 16

15(14) Thermophilic; conidia 2.5–4.5 μm wide......................................................................................................... cinnamomea

Not thermophilic; conidia narrower.................................................................................................................................... pulchella

16(14) Colonies orange.......................................................................................................................................................................... 17

Colonies different.................................................................................................................................................................................... 18

17(16) Aleuroconidia laterally or terminally dispersed.................................................................................... chrysosporoidea

Aleuroconidia absent............................................................................................................................................................. aurantiaca

18(16) Colonies golden yellow, exudate brown, diffusible pigment yellow........................................................ graminicola

Above features not combined..................................................... .........................................................................................................19

19(18) Sexual morph produced by in vitro mating of compatible strains................................................................ albolutea

Sexual morph not formed..................................................................................................................................................................... 20

20(19) Thick-walled brown setae produced on OA from the vegetative mycelium......................................... filamentosa

Setae not produced....................................................................................................................................................................... arcuata

21(13) Fertile hyphae unbranched or scarcely branched............................................................................................................. 22

Fertile hyphae branched........................................................................................................................................................................ 24

22(21) Arthroconidia cylindrical; becoming many septate with the age............................................................ multiseptata

Arthroconidia barrel-shaped, “T”-shaped, “Y”-shaped, finger-shaped or more irregular, mostly unicellular.............. 23

23(22) Arthroconidia barrel-shaped, 4–8 × 2–3.5 μm; racquet hyphae present...................................................... chinensis

Arthroconidia barrel-shaped, “T”-shaped, “Y”-shaped, finger-shaped or more irregular, 2–6 × 1–2 μm; racquet hyphae absent....................................................................................................................................................................... stricta

24(21) Fertile hyphae branching acutely, displaying a tree-like appearance.......................................................... dendritica

Fertile hyphae branching pattern otherwise.................................................................................................................................... 25

25(24) Fertile hyphae repeatedly branched, in dense tufts...................................................................................... flocciformis