Abstract

Objectives:

Conduct a systematic review designed to determine needs and experiences of LGBTQ adolescents in the pediatric primary care setting and to the ability of primary care practitioners to provide the most inclusive care to LGBTQ adolescents.

Methods:

PubMed, CINAHL, and Embase searches using the following keywords: LGBTQ, Adolescents, Pediatrics, Sexual-Minority, Gender-Identity, and primary care, to identify peer-reviewed publications from 1998 to 2017 that focused on stigma in the healthcare setting related to LGBTQ youth and the knowledge of healthcare providers on enhancing care for their sexual and gender minority patients. Article inclusion criteria include: primary research studies conducted in a pediatric primary care describing LGBTQ patients, pediatric patients as described by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and written in the English language. Articles were excluded if they used inaccurate definitions for LGBTQ identity, inappropriate patient ages outside of those defined by the AAP, and studies not in a pediatric primary care setting.

Results:

Four articles were identified for the review. Of the included articles, the majority of LGBTQ adolescents experience stigma in the healthcare setting. A limited number of physicians providing care to LGBTQ adolescents felt equipped to care for their sexual-minority patients due to lack of education and resources.

Conclusions:

The education of physicians should include a more detailed approach to providing care to the LGBTQ population, particularly to those training to become pediatricians. A standard guide to treating LGBTQ adolescents could eliminate stigma in the healthcare setting.

Keywords: children, health outcomes, patient-centeredness, pediatrics, primary care, LGBTQ, adolescent

Introduction/Background

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) adolescents are more likely than their peers to experience stigma in the health care environment and require affirming and inclusive care by providers to effectively treat and monitor their health.1-5 An annual well-child visit with an adolescent should include time spent alone with the healthcare provider so the patient can ask questions about their health without a guardian present to provide an opportunity to address substance use, sexual behavior, and mental health concerns.6-8 Pediatricians are often the first health-care contacts for LGBTQ adolescents who are developing their sexual and gender identities. The current literature suggests that pediatricians have limited knowledge about LGBTQ issues and often do not address sexual orientation or gender identity.9-11

There are 2 existing literature reviews that focus on LGBTQ adolescents in the primary care setting.3,12 Hadland et al3 addresses the unique needs of LGBTQ adolescents and recommendations for providers. This publication does not draw from primary research studies that analyze provider attitudes and beliefs and perspectives from LGBTQ adolescents. Hadland et al3 analyzes the overall healthcare system, but does not provide insight about LGBTQ adolescents in the primary pediatric care setting.

Levine12 analyzes health disparities faced by LGBTQ adolescents and offers guidance about making the healthcare environment more inclusive, creating systems that protect confidentiality of LGBTQ adolescents, obtaining a sexual history, and assisting parents of LGBTQ adolescents.12 While this review was provided recommendations, it did not review studies that survey adolescents and physicians concerning the needs of LGBTQ adolescents and the current practices physicians follow.

Hadland et al3 and Levine12 provide excellent recommendations for improving the healthcare system for LGBTQ adolescents. Both publications highlight the need for improved healthcare for LGBTQ adolescents and appropriately define LGBTQ. They did not focus on the relationship between pediatricians and LGBTQ adolescents and improvements that can be made by providers that address the needs of adolescents from their point of view.

This review answers the following questions: (1) What do LGBTQ adolescent patients identify as gaps in the primary care setting?, and (2) What are the knowledge and attitudes of primary care pediatricians toward LGBTQ adolescent patients? Results may provide insight about how pediatric primary care can be improved to provide quality, patient-centered care to improve LGBTQ pediatric health outcomes.

Methods

PubMed, CINAHL (Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature), and Embase were used to search for relevant literature to include in this review. Key search terms included: LGBTQ, Adolescents, Pediatrics, Sexual-Minority, Gender-Identity, and primary care. There was no limitation on the date of publication.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed, English-language studies that discussed LGBTQ adolescents and health outcomes in the pediatric primary care setting. Adolescents are defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics as ages 11 to 21 years; studies defining adolescents outside this range were excluded. LGBTQ is an acronym for lesbian (female-to-female sexual attraction), gay (male-to-male sexual attraction), bisexual (attraction to same and opposite sex), transgender (identifying as gender not assigned at birth), and queer (encompassing identities and practices, in addition to LGBT, which challenge binaries of sex and gender; e.g, asexual, intersex, gender neutral).13 Studies that include definitions outside of the acronym defined as LGBTQ were excluded.14 Pediatric primary care physicians follow their patients from birth to age 21 and have more opportunities to build trust with patients to discuss sensitive issues relating to LGBTQ-oriented care13; therefore, publications specific to “pediatric primary care” were included while studies of LGBTQ adolescents outside pediatric primary care were excluded.

Search Results

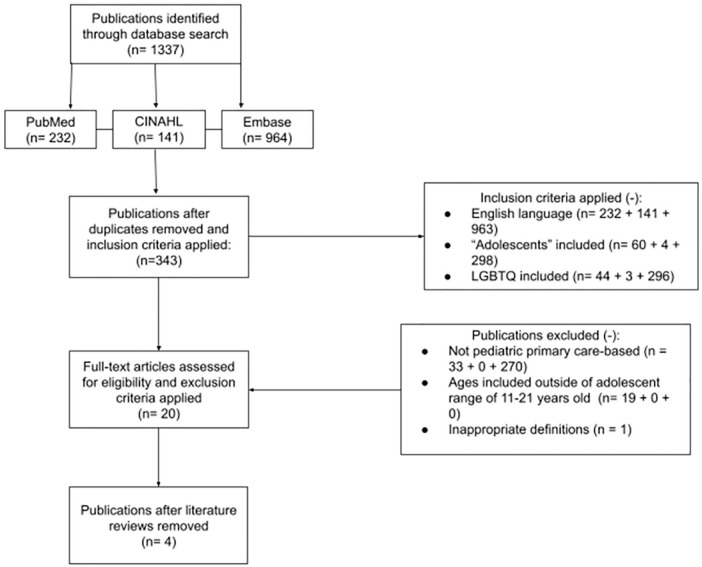

The initial search retrieved 1337 publications (Figure 1). After excluding duplicates, reviewing abstracts, and reviewing titles, excluding non-English publications, and validating the definitions for LGBTQ and the appropriate age-range for adolescents, 343 articles were reviewed in their entirety. After reviewing the 343 articles to completion, 303 did not describe pediatric primary care, while 19 included inaccurate age ranges of adolescents and were removed. One publication did not incorporate the “Q” portion of LGBTQ which is a critical part of defining this population of adolescents.

Figure 1.

Eligibility criteria for publications of quality of care in a pediatric primary care setting for LGBTQ adolescents between January 2010 and September 2020 using key search terms: LGBTQ, adolescents, pediatrics, sexual-minority, gender-identity, and primary care.

Results

Two studies included results from 793 adolescents, and 2 studies included results from 156 residents/physicians. In general, patients felt their needs were not being met, while physicians felt ill-equipped to meet those needs. I discuss these studies below.

Snyder et al15 used a focus group to identify past experiences, needs, and concerns regarding the primary health care received in 5 community-based sites in central and northern New Jersey.15 Sixty self-identified LGBTQ adolescents completed a survey and participated in focus groups to elicit responses about their experiences in the pediatric primary care setting regarding: time spent with the provider, respect in the office, trust, if the provider asked about emotional health, sexual orientation, and safe sex practices.15 One-third of the adolescents reported discussing sexual orientation, sexual practices, or birth control with their pediatrician.15 Only 16.7% responded that their pediatrician asked about their sexual orientation, and 45.6% felt comfortable to speaking about their personal lives.15 71.7% of respondants would prefer LGBTQ-specific clinics to receive care, while those not in favor reported that would make them feel “labeled.”15 While limited by small sample size, this study described first-hand perspectives of LGBTQ adolescents about their healthcare experiences. The results of this study suggest that pediatricians need more awareness of questions to ask LGBTQ adolescents regarding their sexuality and gender identity.

Hoffman et al16 conducted a cross-sectional, internet-based survey of 733 LGBTQ adolescents ages 13 to 21 years living in the U.S. or Canada.16 Three questions asked respondents to write answers in list form and rank each portion of the list.16 The questions included: “what qualities are important to you in a healthcare provider, what qualities are important to you about the office or health center where you get healthcare, and what concerns or problems are important to you to discuss with a healthcare provider.”16 Investigators found that LGBTQ adolescents rank the following as the most important aspects of their primary care experience: “the provider makes them feel comfortable, is non-judgmental, and treats LGBTQ youth the same as other youth”.16 Respondents also cite family issues as important concerns to discuss with a healthcare provider, suggesting that providers should familiarize themselves with the psychosocial issues facing LGBTQ youth, thereby contextualizing these youth within the framework of home and family.16 It is important to note that this study required adolescents to recall experiences with pediatricians, so there could be recall bias. However, this study provides essential information from the first-hand expectations and experiences of adolescents in the primary care setting.

In addition to assessing the needs of LGBTQ adolescents in the primary care setting, it is also important to understand the experiences providers have relating to LGBTQ adolescents. From 1998 to 2019, Zelin et al17 surveyed pediatric residents’ beliefs and behaviors about healthcare for sexual and gender minority youth. Results indicated that 6% of current residents would be afraid of offending parents with discussions of sexuality and gender identity compared to 32% of residents feeling afraid of this topic in the past.17 However, 45% of current residents said they may not know enough about sexual minority needs to have discussions about sexuality and gender identity, compared to 47% in previous studies.17 This study is limited by a small sample size (n = 48) from a single institution, but is useful because it presents data from the past to present pediatric residents, allowing for a comparison of the progress pediatricians are making to enhance the knowledge about LGBTQ issues in the healthcare setting.

The final publication surveyed 108 residents and attending physicians across multiple specialties that see pediatric patients at Update Medical University. The survey included questions pertaining to practice, knowledge, and attitude concerning LGBTQ adolescents. Kitts10 found that the majority of physicians would not regularly discuss sexual orientation, sexual attraction, or gender identity while taking a sexual history from a sexually active adolescent.10 In addition, the survey found that only 14% of physicians would regularly question an adolescent’s sexual orientation in those who presented with depression, suicidal thoughts, or had attempted suicide.10 Finally, only 8.5% of respondents would regularly discuss gender identity while taking a sexual history from an adolescent and only 29% would regularly discuss sexual orientation.10 The survey found that less than 50% of physicians agreed that they had all the skills they needed to address issues of sexual orientation and gender identity.10 This study presents useful information from healthcare providers across specialties (pediatrics, emergency medicine, OBGYN, psychiatry, internal medicine, and family medicine) that treat and care for adolescents. The study is limited by a small sample size drawn from a single institution.

Discussion

The findings of this review support the need for increased awareness and knowledge of the healthcare needs of LGBTQ adolescents. For example, providing LGBTQ-affirming environments within the primary care setting (having LGBTQ-affirming symbols on provider ID badges, LGBTQ-relevant reading material in waiting rooms, etc.), mandating LGBTQ-specific education for providers and healthcare workers, formulating an electronic medical record system that eliminates confusion on patient gender identity, including questions relating to sexuality and gender in the intake process with patients and families, and evaluating the level of support LGBTQ adolescents have in and out of the primary care setting. Implementing the aforementioned measures have the possibility of creating feelings of trust and safety between the LGBTQ adolescent and provider.

Pediatricians follow their patients from birth to their early twenties, providing ample opportunity to establish trust and discuss personal issues that relate to their health. However, in the context of caring for LGBTQ adolescents, physicians report that they feel underprepared to talk about sexuality and gender identities. The LGBTQ adolescents surveyed support that their healthcare needs are not being met in the primary care setting. LGBTQ adolescents report that they are not asked about their sexuality or gender identity by their pediatrician. The comparison of pediatricians and LGBTQ adolescents support the need for improved education regarding LGBTQ interviewing. Improved understanding of issues LGBTQ adolescents face by the healthcare provider could improve health outcomes; specifically in regards to mental health and sexual health.

This review indicates that there is extremely limited research that assesses the unique needs of LGBTQ adolescents in the primary care setting and how pediatricians are responding to these needs to improve health outcomes. Overall, while there are some concerns about bias in these studies (eg, selection bias in an internet based study, as well as lack of information about dropouts from Hoffman et al16), the studies were relatively free from bias. In addition to these biases, the small number of LGBTQ adolescents identified may have been affected by social desirability bias. Adolescence often comes with uncertainty, and sexuality and gender identity are no exception. A concern identified by HealthyPeople.gov18 2020 is whether sexual orientation and gender identity is measured appropriately in population-based surveys. Bias in measuring sexual orientation and gender identity may produce inaccurate estimates of LGBTQ individuals, compounded by small sample size. The results of this review should be considered in light of the small number of articles meeting inclusion criteria and the different populations targeted and included in the studies. Overall, the findings of this review suggest opportunities for researchers to pursue studies comparing the knowledge of pediatricians in terms of LGBTQ care for adolescents, how they approach conversations concerning sexual and gender identity, and health outcomes of their LGBTQ adolescent patients after receiving appropriate counseling and open conversation. In addition, it would be helpful to learn more about the experiences of LGBTQ adolescents in the primary care setting. This could provide further opportunity to improve the education of pediatricians when caring for their LGBTQ adolescent patients.

Conclusion

The results of this review indicate that physicians do not feel prepared or comfortable to interact with LGBTQ adolescents. In addition, LGBTQ adolescents do not feel as though their unique needs are being met. These results may provide an impetus for researchers to pursue studies about knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes of pediatricians who care for LGBTQ adolescents. Future research should explore the experiences of LGBTQ adolescents in the primary care setting. Results of this research could provide further opportunity to improve the education of pediatricians who care for LGBTQ adolescent patients.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Molly Stern  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7342-868X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7342-868X

References

- 1.Choice Reviews Online. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding. Choice Rev Online. 2012;49(5):49-2699. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkerson JM, Rybicki S, Barber CA, Smolenski DJ.Creating a culturally competent clinical environment for LGBT patients. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2011;23(3):376-394. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadland SE, Yehia BR, Makadon HJ.Caring for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth in inclusive and affirmative environments. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):955-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz D.Cultural competence in psychosocial and psychiatric care. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;39(3-4):231-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yehia BR, Calder D, Flesch JD, et al. Advancing LGBT health at an academic medical center: a case study. LGBT Health. 2015;2(4):362-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Megan A, Moreno M. The well-child visit. 2018. Accessed November 22, 2020. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2661144 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Nordin JD, Solberg LI, Parker ED. Adolescent primary care visit patterns. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(6):511-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris SK, Aalsma MC, Weitzman ER, et al. Research on clinical preventive services for adolescents and young adults: where are we and where do we need to go? J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(3):249-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lena S, Wiebe T, Jabbour M.Pediatricians’ knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes towards providing health care for lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Ann R Coll Physicians Surg Can. 2002;35(7):406-410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitts RL.Barriers to optimal care between physicians and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescent patients. J Homosex. 2010;57(6):730-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shires DA, Stroumsa D, Jaffee KD, Woodford MR.Primary care clinicians’ willingness to care for transgender patients. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(6):555-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine DA.Office-based care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e297-e313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardin AP, Hackell JM.Age limit of pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20172151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peel E. LGBTQ psychology. Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology; 2014: 1075-1078. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder BK, Burack GD, Petrova A.LGBTQ youth’s perceptions of primary care. Clin Pediatr. 2017;56(5):443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman ND, Freeman K, Swann S.Healthcare preferences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning youth. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3):222-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zelin NS, Encandela J, Van Deusen T, Fenick AM, Qin L, Talwalkar JS.Pediatric residents’ beliefs and behaviors about health care for sexual and gender minority youth. Clin Pediatr. 2019;58(13):1415-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Healthypeople.gov. Accessed November 22, 2020https://www.healthypeople.gov/202c0/topis-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health