Abstract

Background and Objectives

Opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome (OMS) is a rare autoimmune disorder associated with neuroblastoma in children, although idiopathic and postinfectious etiologies are present in children and adults. Small cohort studies in homogenous populations have revealed elevated rates of autoimmunity in family members of patients with OMS, although no differentiation between paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic forms has been performed. The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence of autoimmune disease in first-degree relatives of pediatric patients with paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic OMS.

Methods

A single-center cohort study of consecutively evaluated children with OMS was performed. Parents of patients were prospectively administered surveys on familial autoimmune disease. Rates of autoimmune disease in first-degree relatives of pediatric patients with OMS were compared using Fisher exact t test and χ2 analysis: (1) between those with and without a paraneoplastic cause and (2) between healthy and disease (pediatric multiple sclerosis [MS]) controls from the United States Pediatric MS Network.

Results

Thirty-five patients (18 paraneoplastic, median age at onset 19.0 months; 17 idiopathic, median age at onset 25.0 months) and 68 first-degree relatives (median age 41.9 years) were enrolled. One patient developed systemic lupus erythematosus 7 years after OMS onset. Paraneoplastic OMS was associated with a 50% rate of autoimmune disease in a first-degree relative compared with 29% in idiopathic OMS (p = 0.31). The rate of first-degree relative autoimmune disease per OMS case (14/35, 40%) was higher than healthy controls (86/709, 12%; p < 0.001) and children with pediatric MS (101/495, 20%; p = 0.007).

Discussion

In a cohort of pediatric patients with OMS, there were elevated rates of first-degree relative autoimmune disease, with no difference in rates observed between paraneoplastic and idiopathic etiologies, suggesting an autoimmune genetic contribution to the development of OMS in children.

Opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome (OMS) is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the triad of involuntary rapid eye movements, myoclonus, and ataxia.1 Roughly 50% of cases in children are paraneoplastic (neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma), whereas the remainder are infection associated or idiopathic.1,2 Based on CSF findings, pathologic studies, and response to immunosuppressive therapy, OMS is considered to be an autoimmune disorder.

One approach to understanding the underlying pathogenic mechanisms in autoimmune disorders is to examine whether there are associated comorbid personal and familial autoimmune diseases. One European study reported autoimmune disease in 15.8% of parents of children with OMS compared with 2% of control parents.3 This finding has not been assessed in other OMS populations, nor have there been comparisons of autoimmune family histories between patients with and without a paraneoplastic etiology.

This study sought to investigate the prevalence of autoimmune diseases in first-degree relatives of pediatric patients with OMS and to compare the rate (1) between those with and without a paraneoplastic cause and (2) to the comparable rates in healthy and disease (pediatric multiple sclerosis [MS]) controls.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Boston Children's Hospital (BCH). Following approval, all patients with OMS who were subsequently seen in the senior author's (M.P.G.) clinic were offered enrollment between April 2018 and March 2019 (dates of first and last enrollment). Consent, and where appropriate assent (ages 7–17 years), was obtained for study participation.

Data Collection

Clinical information for patients was abstracted retrospectively using a predetermined case report form through chart review of institutional and outside medical records when available (eAppendix 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A577). CSF data collected included white blood cell count (range 0–5 cells/mm3) with differential and oligoclonal banding (abnormal if present). First-degree relative was defined as a biologic parent or sibling. Family autoimmune disease was collected prospectively by administering a survey with highly prevalent autoimmune diseases listed to parents of patients (eAppendix 2, links.lww.com/NXI/A578). The same survey had been used in an IRB-approved study of familial autoimmune disease in pediatric MS in the Network of Pediatric MS Centers (NPMSC) with data collected prospectively in a longitudinal cohort at 18 centers (including BCH) enrolled from May 2011 to July 2017.

Statistical Analysis

Mean and median values were calculated for all continuous variables, and frequency (expressed as a percentage of the total population) was calculated for noncontinuous variables. For continuous variables, Welch t tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare means. Interquartile ranges were calculated for continuous variables. The Fisher exact test was used to compare prevalence of autoimmune disease between patients with paraneoplastic and idiopathic OMS. The rate of first-degree relative autoimmune disease on a case level in the OMS cohort was compared using χ2 analysis to the same rates found in patients with pediatric MS and autoimmune disease-free controls in the NPMSC study. For a sensitivity analysis, we also used the BCH-specific data for comparison. Age at onset of first-degree relative autoimmune disease was compared between the OMS cohort and comparator groups using a Mann-Whitney U test. A nominal p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for each statistical test.

Data Availability

Deidentified data, statistical analysis, and study documents will be available on request to qualified researchers pending IRB approval.

Results

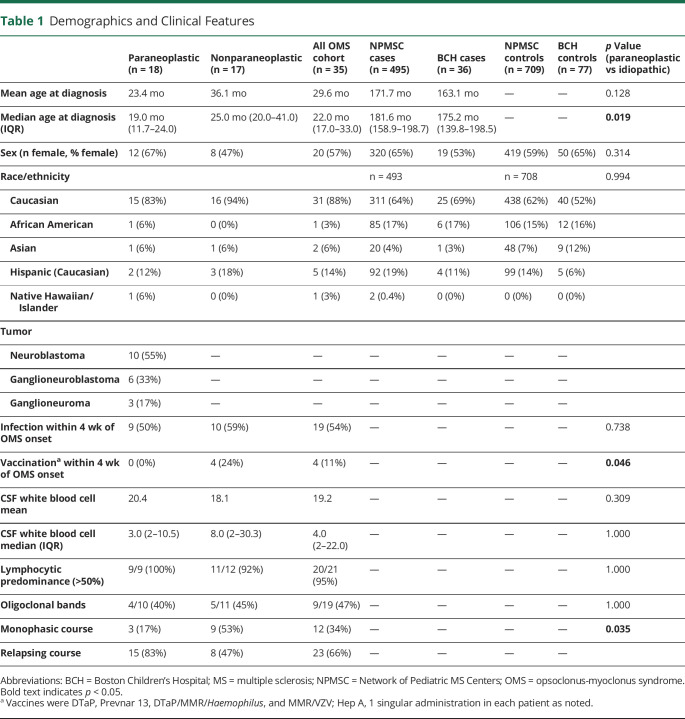

Thirty-five patients and 68 first-degree relatives (biological parents) were enrolled. Two parents (of different patients) were not available. No siblings were reported to have autoimmune disease (n = 43, median age 3.8 years [interquartile range [IQR]: 2.5–7.4]). Demographic and clinical data are reported in Table 1. The median follow-up time for individuals with OMS was 8.11 years (IQR: 2.8–11.5 years). Eighteen patients had paraneoplastic OMS (median age at onset 19.0 months, IQR 11.7–24.0 months), and 17 patients had nonparaneoplastic OMS (median onset 25.0 months, IQR 20–72.5 months) (p = 0.019 for age at onset). All tumors were of neural crest cell origin, with neuroblastoma being the most common (55%). There were no significant differences between groups with regard to preceding infection, CSF white blood cell number, or presence of CSF oligoclonal bands (Table 1). All patients vaccinated within 4 weeks of symptom onset (n = 4) were diagnosed with nonparaneoplastic OMS, although the specific vaccine(s) administered was different in each case (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis [DTaP], Prevnar 13/Hepatitis A, DTaP/measles, mumps, rubella [MMR]/Haemophilus, and MMR/varicella zoster virus [VZV]). Paraneoplastic OMS had a rate of 50% of autoimmune disease in a first-degree relative compared with 29% in nonparaneoplastic OMS (x2 [1, N = 34] = 1.54, p = 0.31).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Features

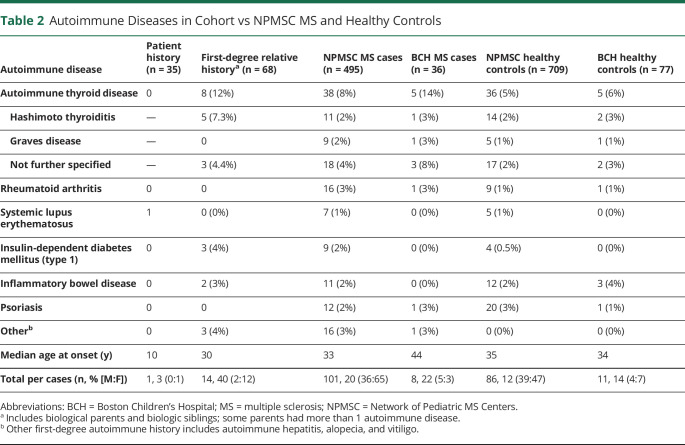

Patient and family autoimmune diseases are presented in Table 2. One patient in our cohort developed systemic lupus erythematosus 7 years after nonparaneoplastic OMS diagnosis and treatment. Fourteen patients (40%) had at least 1 first-degree family member with an autoimmune disease, accounting for 21% of all parents with children with OMS. Compared with previously published data,3 this cohort had a similar rate of familial autoimmune disease (13/82, 15.2%; x2 [1, N = 149] = 0.56, p = 0.45). The most common autoimmune diseases among first-degree relatives were thyroid disease (n = 8/68, 12%), followed by type 1 diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease (n = 3/68, 4% and n = 2/68, 3%, respectively). The majority (n = 12/14, 86%) of first-degree relatives with autoimmune disease were female (x2 [1, N = 67] = 5.79, p = 0.016).

Table 2.

Autoimmune Diseases in Cohort vs NPMSC MS and Healthy Controls

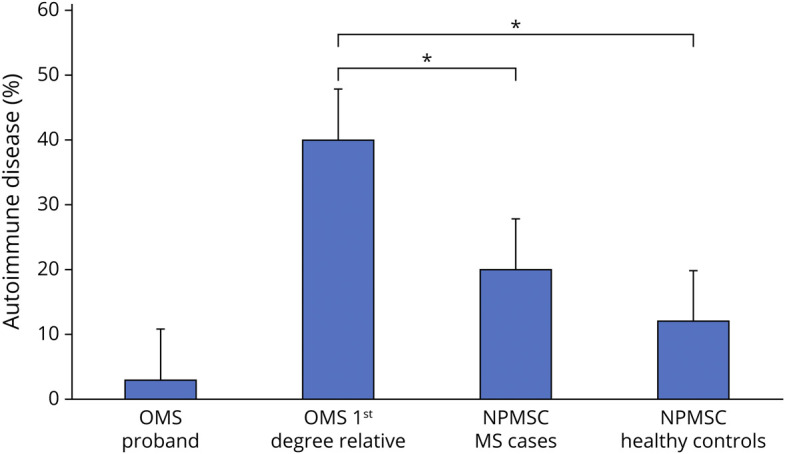

The rate of first-degree relative autoimmune disease was significantly higher in the OMS cohort (n = 14/35, 40%) compared with the same rate in the pediatric MS (n = 101/495, 20%) (x2 [1, N = 530] = 7.39, p = 0.007) and healthy control cohorts (n = 86/709, 12%) (x2 [1, N = 734] = 22.27, p < 0.001) (Figure). The comparison did not change significantly when using BCH site-specific level for pediatric MS (n = 8/36, 22%) and healthy controls (n = 11/77, 14%).

Figure. Prevalence of Autoimmune Disease by Cohort.

Age at onset for autoimmune disease in first-degree relatives in the OMS cohort was 30 years and was significantly younger compared with the age at onset (34 years) in the combined group of first-degree relatives with autoimmune disease in the pediatric MS and healthy control cohorts (p < 0.001, 95% CI: 5.49–6.51). Sixty-four percent of first-degree relatives had onset before birth of the proband with OMS.

Discussion

This study identified high rates of familial autoimmune disease in patients with both paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic OMS. When analyzed on a per-parent basis to allow for comparison, the rate of autoimmune disease in our study (14/68, 21%) was similar to a prior study in OMS (13/82, 15.8%, p = 0.45).3

Our study adds to the growing literature that the paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic forms of OMS are more similar than different.3 We identified no difference in rates of familial autoimmune disease between paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic forms of OMS. One proposed hypothesis to explain nonparaneoplastic cases is that the host immune response eliminated a previous neural crest cell tumor, which therefore would not be detected at OMS onset. From this perspective, high rates of familial autoimmune disease suggest that the antitumor immune response in OMS may be driven by variants in genes involved in autoimmune disease. The oncologic outcome of neuroblastoma is significantly better in children with OMS compared with those without OMS. Further understanding of specific genetic variants that contribute to OMS expression in neuroblastoma may provide a window into harnessing the salutary effects of the immune system response to neuroblastoma more generally.

An alternative hypothesis is that there are different triggers in nonparaneoplastic compared with paraneoplastic cases, with infections being commonly reported. However, rates of preceding infection did not differ between the paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic subgroups in our study. This finding, along with high rates of familial autoimmune disease in both subgroups, suggests that the expression of OMS may be driven more by genetic susceptibility than the specific antigenic trigger.

Our cohort also captured a higher rate of autoimmune disease in first degree than in pediatric MS and healthy controls. We also report the post-OMS development of systemic lupus erythematosus in a patient. These results are of even greater importance in the context of the younger age at onset for OMS, allowing for less time for parental development of autoimmune disease. The majority of parents had onset of their autoimmune disorder before the birth of the proband with OMS. There are emerging data on the role of maternal immune activation contributing to the development of both autoimmune disease and neuropsychiatric disease in offspring. Whether this plays a role in OMS requires further research.4

Our results can be viewed within the context of existing literature demonstrating the role of genetic susceptibility in a variety of autoimmune diseases in children.5-8 One prior study showed higher rates of the HLA-DRB1*01 allele in children with OMS (with or without neuroblastoma) compared with controls.6 Further studies using modern genetic techniques such as whole-genome sequencing assessing a wider array of genes may identify additional genes involved in the development of OMS. The variety of autoimmune disease captured in this study supports the theory that multiple genes and related immune pathways may be at play.9,10

This study is not without limitation. Our sample size was comparable to other studies in OMS, but nonetheless small, in part owing to the rarity of OMS. Recall bias cannot be excluded in familial reporting of autoimmune diseases, which potentially confounds our data. Diagnoses in relatives were not verified by direct review of their medical records. Probands in this study had prolonged follow-up (median: 8.11 years), although given that the majority of autoimmune diseases present in early adulthood, it is possible that the rate of autoimmune disease reported in them and their siblings may be underestimated. Controls could not have an autoimmune disorder, which may have decreased the rate of parental autoimmune disease; however, this restriction did not apply to the pediatric patients with MS. We did not include a group of children with neuroblastoma without OMS, which would be an important topic for future work. Finally, the reporter (mother vs father) of family history of autoimmune disease was not recorded in this study and may potentially affect the quality of data reported.

In a cohort of pediatric patients with OMS, elevated rates of first-degree autoimmune disease exist without significant differences in rates between paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic forms. These data suggest that genetic predisposition may be more important than the triggering antigen in the pathogenesis of OMS. Further genetic interrogation in this population is warranted.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all collaborators through the US Network of Pediatric MS Centers who provided data for statistical comparison.

Glossary

- OMS

opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome

- BCH

Boston Children's Hospital

- DTaP

diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis

- IQR

interquartile range

- MMR

measles, mumps, rubella

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NPMSC

Network of Pediatric MS Centers

Appendix. Authors

Contributor Information

Lauren M. Kerr, Email: lauren.kerr@cardio.chboston.org.

Rachel Codden, Email: rachel.codden@hsc.utah.edu.

Theron Charles Casper, Email: charlie.casper@hsc.utah.edu.

Benjamin M. Greenberg, Email: benjamin.greenberg@utsouthwestern.edu.

Emmanuelle Waubant, Email: emmanuelle.waubant@ucsf.edu.

Sek Won Kong, Email: sekwon.kong@childrens.harvard.edu.

Kenneth D. Mandl, Email: kenneth.mandl@childrens.harvard.edu.

Mark P. Gorman, Email: mark.gorman@childrens.harvard.edu.

Study Funding

This study was supported by the Precision Link Biobank for Health Discovery at Boston Children's Hospital and Pfizer, Inc.

Disclosure

J.D. Santoro reports receiving research funding from the Race to Erase MS Foundation, Thrasher Foundation, and National Institutes of Health. L. Kerr, R. Codden, T.C. Casper, B.M. Greenberg, E. Waubant, S.W. Kong, and K.M. Mandl report no disclosures. M.P. Gorman reports receiving research funding from Roche as a pediatric multiple sclerosis clinical trial site. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Ratner N, Brodeur GM, Dale RC, Schor NF. The “neuro” of neuroblastoma: neuroblastoma as a neurodevelopmental disorder. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(1):13-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthay KK, Blaes F, Hero B, et al. Opsoclonus myoclonus syndrome in neuroblastoma a report from a workshop on the dancing eyes syndrome at the advances in neuroblastoma meeting in Genoa, Italy, 2004. Cancer Lett. 2005;228:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krasenbrink I, Fühlhuber V, Juhasz-Boess I, et al. Increased prevalence of autoimmune disorders and autoantibodies in parents of children with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome (OMS). Neuropediatrics. 2007;38:114-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones HF, Ho ACC, Sharma S, et al. Maternal thyroid autoimmunity associated with acute-onset neuropsychiatric disorders and global regression in offspring. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(8):984-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ceccarelli F, Agmon-Levin N, Perricone C. Genetic factors of autoimmune diseases. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:3476023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li YR, Li J, Zhao SD, et al. Meta-analysis of shared genetic architecture across ten pediatric autoimmune diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21:1018-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hero B, Radolska S, Gathof BS. Opsomyoclonus syndrome in infancy with or without neuroblastoma is associated with HLA DRB1*01 [Abstract]. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:S365-S588. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pociot F, Lernmark Å. Genetic risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2016;387:2331-2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pranzatelli MR, Travelstead AL, Tate ED, et al. B- and T-cell markers in opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome: immunophenotyping of CSF lymphocytes.. Neurology. 2004;62:1526-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pranzatelli MR, Travelstead AL, Tate ED, et al. Immunophenotype of blood lymphocytes in neuroblastoma-associated opsoclonus-myoclonus. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26:718-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data, statistical analysis, and study documents will be available on request to qualified researchers pending IRB approval.