Abstract

Introduction:

Microneedling radiofrequency (MNRF) using insulated microneedles offers a great advantage to overcome the limitations of fractional lasers such as achieving greater depth, long downtime, and high risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH).

Aims:

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy and safety of a novel multiple depth bipolar rotational stamping and monopolar criss-cross method (Wosyet vital technique) with MNRF using insulated needles for the improvement of facial acne scars in Asians.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty-two patients (20 females, 12 males, average age 30.3 years) with facial atrophic acne scars were treated with insulated MNRF by applying Wosyet vital technique. Most of the patients started noticing improvement in 4–6 weeks after the first session. All patients underwent four sessions at 1-month interval. Outcome assessments included subjective and physician evaluation of acne scars, pores, smoothness, tightness, and overall appearance. Objective assessment was determined by Goodman and Baron’s quantitative and qualitative analysis of the acne scars.

Results:

All subjects noticed at least 30%–90% (mean––62.50%) improvement in acne scars, whereas unbiased physicians graded 40%–80% (mean––58.44%) at a 6-month follow-up visit. The mean Goodman and Baron’s score decreased significantly from pre- to posttreatment. All patients reported 30%–90% (mean––61.88%) improvement in facial contour and skin tightening. Many patients observe improvement in the open pores as well.

Conclusion:

The possible explanation of improvement in the global appearance of skin and acne scars is the application of both monopolar and bipolar RF in the dermis through insulated microneedles. We did not find PIH after this technique in Asian patients despite of more aggressive treatment parameters and several treatment sessions.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The results were analyzed using chi-square test, Wilcoxon sign rank test, Pearson’s correlation test, Spearman’s correlation test, and paired t test.

Keywords: Bipolar, insulated microneedles, MNRF, monopolar, Wosyet vital technique

Key Messages: Multiple depth bipolar rotational stamping and monopolar criss-cross method with insulated MNRF is safe and treat acne scars very effectively in Asians.

INTRODUCTION

Atrophic scars are caused by compromised collagen production during the natural wound healing process following an inflammatory response to acne, which results in surface irregularities.[1] Acne scars can be classified as ice pick, rolling, and boxcar scar (shallow and deep). They can be atrophic or hypertrophic.[2,3]

Several modalities have been implicated to treat atrophic acne scarring, including invasive: surgical techniques (subcision, surgical scar revision, punch grafts, and excisions), autologous fat transfer, CROSS technique with 100% TCA, electrosurgical planning, injection of dermal fillers, and dermabrasion.[4,5,6] Non-invasive treatments include cryotherapy, chemical peels, and laser therapy (non-ablative and ablative).[7] Combinations of modalities have also been used.[8]

Fractional photothermolysis, as a concept, was introduced to overcome the drawbacks of ablative and nonablative resurfacing systems.[9,10] The conventional fractional ablative laser systems have limitations of achieving greater depth, more discomfort, long downtime, and high risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH). Nonablative fractional lasers (1540 nm erbium glass) have the advantages of less downtime along with providing good efficacy. However, their clinical efficacy does not match that of the full ablative process, especially for moderate-to-severe atrophic acne scars.[11,12,13] The introduction of fractional microneeedling radiofrequency technology (MNRF) is expected to overcome the limitations of fractional lasers.

MNRF is a minimally invasive nonablative system which delivers both mono- and bipolar RF energy in the form of an electrical current which causes generation of heat through the inherent electrical resistance of dermal and subcutaneous tissue.[14] It creates radiofrequency thermal zones (RFTZ) without epidermal injury, which results in neoelastogenesis and neocollagenosis, thus leading to dermal thickening.[15] By fractionating RF energy over multiple insulated electrodes, the regions of controlled damage are surrounded by zones of normal tissue, reducing the pain, shortening the downtime, and accelerating the healing process.[16] An advantage of fractional radiofrequency is that it causes less epidermal disruption by less than 5%, compared with 10%–70% of that of fractional ablative laser systems.[17,18] MNRF using insulated electrodes offers a great advantage over fractional lasers. The key differences of insulated MNRF when compared to fractional lasers are as follows:

- It can be used for all skin types, with negligible risk of skin burns and PIH especially with darker skin complexion.

- Delivered RF energy is specifically focused at the tip of the microneedles, leading to very less injury to the epidermis. Thus, there is a far less down time and pain for the patient as compared to a conventional CO2 fractional laser.

- The maximum depth achieved safely with fractional lasers is 1 to 1.5 mm in dark skin individuals. Microneedle penetration depth can be adjusted from 0.5 to 3 mm which makes it effective in treating even deeper scars.

There have been few studies evaluating the efficacy of insulated fractional MNRF in the treatment of acne scars and there is still a dearth of scientific data and literature on the optimum techniques and results that can be obtained.

Objectives

The objective of the study was to assess the efficacy and safety of a novel bipolar rotational stamping and monopolar criss-cross method (Wosyet vital technique) with MNRF using insulated needles for the improvement of facial acne scars in Asians.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Population of the study

In this single-center, prospective, self-controlled clinical study, 32 patients (20 females and 12 males) with facial atrophic acne scars and Fitzpatrick skin type III to V, who attended the OPD of a private Dermatology center between 2016 and 2018 were included. An oral and informed written consent was obtained from each patient before starting the procedure. The exclusion criteria of the study were active inflammation, history of Keloid scar, connective tissue disorders, bleeding disorders, pregnancy or lactation, and ablative or nonablative laser skin resurfacing within the preceding 12 months.

Treatment procedure

In all subjects, both sides of the face were treated with MNRF (INTRAcel, Jeisys Medical, Seoul, Korea) having insulated electrodes emitting both monopolar and bipolar radiofrequency.

Anesthesia procedure

The treatment areas were cleaned with a mild cleanser and disinfected with 70% isopropyl alcohol. A topical mixture of lidocaine, 2.5% and prilocaine, 2.5% cream (a eutectic mixture of local anesthetic) was applied under occlusion on the treatment area for an hour prior to each treatment. For the initial few patients, the anesthetic cream was completely removed from the entire face before performing the procedure. Patients experienced pain during the procedure as the effect started waning off after sometime. This technique was later modified during the study period. For the rest of the patients, the anesthetic cream was only removed from the side of the face to be treated and was left under occlusion on the other side. After performing the procedure on the one side, cream from the other side was then removed and treatment was done. Pain decreased substantially after the refinement in the anesthesia technique later in the study.

Treatment protocol

All patients received four treatments at 1-month interval and then assessed 6 months after the last session. Identical treatment techniques were performed on all patients by a single physician. Subcision was not done in any patient before treatment and no other treatment modalities were combined during the whole study period. All the patients were treated with a unique combination of multiple depth bipolar rotational stamping and monopolar criss-cross method with MNRF using insulated needles. Treated area was kept dry by using sterile gauze to avoid slipping of the probe especially on nose and periorbital region.

The length of the needles used was limited to 1.5 mm over the forehead and 2 mm over the cheek areas. The treatment protocol was followed as shown in Table 1. Very high energy was avoided while treating with needle depth of 0.5 mm.

Table 1.

Treatment protocol

| Session | Level | Voltage (RMS) | Time (ms) | watt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First treatment | Level 3 | 50 | 10 | 12.5 |

| Second treatment | Level 3 | 50 | 10 | 12.5 |

| Third treatment | Level 4 | 50 | 20 | 12.5 |

| Fourth treatment | Level 4 | 50 | 20 | 12.5 |

Wosyet vital technique

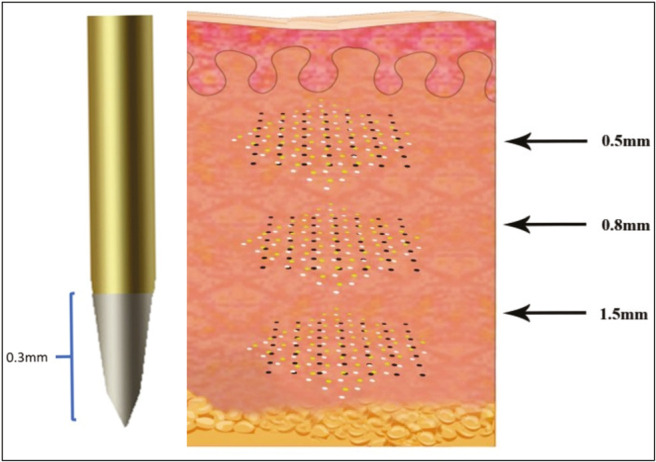

Initial treatment was done by the rotational stamping at multiple depths for individual scars. In the rotational method, the initial needle length of 1.5 mm was selected and treatment was performed using bipolar RF mode. The probe was then rotated at 30° angles with each shot in a circular motion around a single axis till the scar and scar rim constituting some normal tissue were uniformly covered. A total of three shots were given. A subsequent rotational stamping treatment was done on the same scar by reducing the needle length to 0.8 mm and 0.5 mm. This was done to ensure the complete treatment of each of the individual scars using high RF energy without damaging epidermis [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Bipolar multiple depth rotational stamping technique

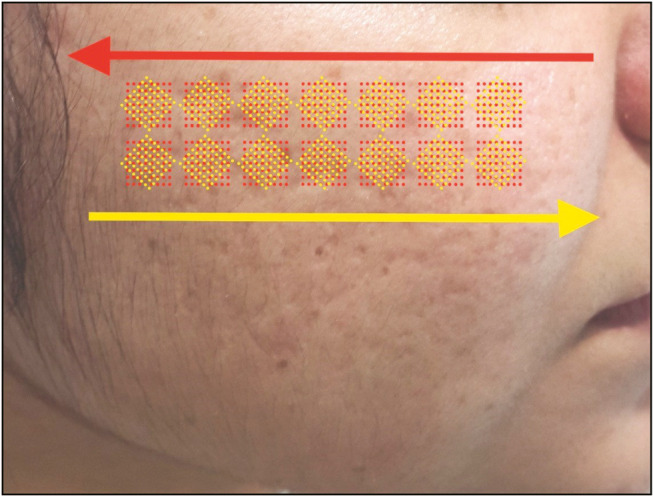

It was then followed by criss-cross treatment of the whole side of face using monopolar RF mode. While performing criss-cross treatment, the needle depth was adjusted to 2 mm and the probe is first moved along a line and then after changing the orientation by 45°, it is moved back along the same line in a reverse direction [Figure 2]. This ensured 2 passes of monopolar RF over the entire treatment area. The same technique was then repeated on the other side of the face.

Figure 2.

Monopolar criss-cross technique

Cold gauzes were kept on the treated areas, which was followed by application of mild steroid-antibiotic cream and sunscreen. Efficacy and side effects were assessed at each treatment visit.

Treatment evaluation

Serial photographs were taken at baseline, before each treatment session and 6 months after the last treatment. Two nontreating dermatologists performed all investigator global assessments before each treatment and 6 months after the last treatment.

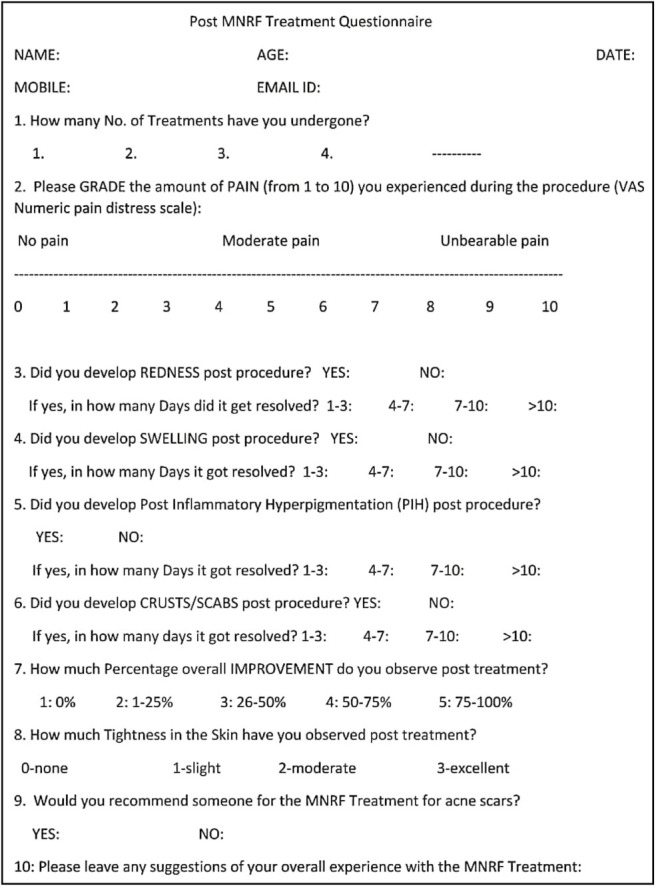

Subjective evaluation

All patients were asked to fill a set of questionnaire 6 months after their last treatment in which they were asked to evaluate their experience with the treatment as well as the improvement in their scars posttreatment [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Post MNRF treatment questionnaire

Objective assessments

The objective analysis of the treatment results was done on three scales.

Global investigator’s assessment

A global investigator’s assessment of overall improvement including scarring, texture, and pigmentation based on a four-grade scale was used to assess the improvement in the scars [Table 2].

Table 2.

Global investigator’s assessment

| Grade 0 | 0% | No improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | 1%–25% | Minimal improvement |

| Grade 2 | 26%–50% | Moderate improvement |

| Grade 3 | 51%–75% | Marked improvement |

| Grade 4 | 75%–80% | Near total improvement |

Goodman and Baron’s scoring[19, 20]

Objective assessment of physician scores of improvement was determined by global acne scarring classification of Goodman and Baron [Tables 3–5]. Both quantitative and qualitative analysis of the acne scars was done.

Table 3.

Goodman and Baron’s qualitative score

| Grade of post acne scarring | Level of disease | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Macular | These scars can be erythematous, hyper-or hypopigmented flat marks. They do not represent a problem of contour like other scars grades but of color. |

| Grade 2 | Mild | Mild atrophic or hypertrophic scars that may not be obvious at social distance of 50 cm or greater and may be covered adequately by makeup or the normal shadow of shaved beard hair in men or normal body hair if extrafacial |

| Grade 3 | Moderate | Moderate atrophic or hypertrophic scars that is obvious at social distance of 50 cm or greater and is not covered by makeup or the normal shadow of shaved beard hair in men or normal body hair if extrafacial but is still able to be flattened by manual stretching of the skin (if atrophic) |

| Grade 4 | Severe | Severe atrophic or hypertrophic scars that is evident at social distance greater than 50 cm and is not covered easily by makeup or the normal shadow of shaved beard hair in men or normal body hair if extrafacial and is not flattened by manual stretching of the skin |

Table 5.

Assessment of improvement using Goodman and Baron’s quantitative acne scar grading system

| Grades | Improvement status |

|---|---|

| 0–5 | Minimal reduction in GSGS scores |

| 5–10 | Moderate reduction in GSGS scores |

| 10–15 | Good reduction in GSGS scores |

| >15 | Very good reduction in GSGS scores |

Table 4.

Goodman and Baron’s quantitative global acne scarring system

| Grade or type | Number of lesions 1 (1–10) | Number of lesions 2 (11–20) | Number of lesions 3 (>20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Milder scarring (1 point each) Macular erythematous pigmented mildly atrophic dish-like | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points |

| (B) Moderate scarring (2 points each) Moderately atrophic, dish like punched out with shallow bases small scars (<5 mm) shallow but broad atrophic areas | 2 points | 4 points | 6 points |

| (C) Severe scarring (3 points each) Punched out with deep but normal bases, small scars (<5 mm) punched out with deep but abnormal bases, small scars (<5 mm) linear or troughed dermal scarring deep, broad atrophic areas | 3 points | 6 points | 9 points |

| (D) Hyperplastic Papular scars keloidal/hypertrophic scars | 2 points area <5 mm 6 points | 4 points Area 5–20 cm2 12 points | 6 points area >20 cm2 18 points |

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0 for Windows. The results were analyzed using chi-square test, Wilcoxon sign rank test, Pearson’s correlation test, Spearman’s correlation test, and paired t test. Significance levels for all analyses were set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

All 32 patients who were enrolled in the study completed the study. Most of the patients had mixed type of atrophic acne scars including ice-pick, boxscar, and rolling scars. All patients underwent four sessions of MNRF treatment using Wosyet vital technique. Patient characteristics, observations, and results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Master chart depicting details and results of all patients

| S. | Age | Sex | Sessions | Pain (0–10) | Redness (days) | Swelling (days) | Improvement experienced by patient % | Tightness experienced by patient % | GBQL pre | GBQL post | GBQL diff | GBQN pre | GBQN post | GBQN diff | Overall improvement observed by physician % | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | F | 4 | 7 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 40 | 40 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 60 | |

| 2 | 31 | F | 4 | 4 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 40 | 40 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 40 | |

| 3 | 35 | F | 4 | 7 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 80 | 90 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 12 | 9 | 50 | Improvement in open pores |

| 4 | 30 | F | 4 | 3 | Yes (1–3) | No | 40 | 40 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 50 | |

| 5 | 34 | M | 4 | 4 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 60 | 70 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 12 | 10 | 70 | |

| 6 | 26 | F | 4 | 5 | Yes (4–7) | Yes (4–7) | 70 | 80 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 8 | 60 | |

| 7 | 25 | M | 4 | 6 | Yes (4–7) | Yes (1–3) | 40 | 30 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 40 | Improvement in open pores |

| 8 | 31 | M | 4 | 6 | Yes (4–7) | Yes (1–3) | 60 | 50 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 21 | 4 | 17 | 60 | |

| 9 | 24 | F | 4 | 8 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 70 | 80 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 8 | 50 | |

| 10 | 38 | F | 4 | 7 | Yes (4–7) | Yes (1–3) | 90 | 90 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 27 | 6 | 21 | 80 | |

| 11 | 36 | F | 4 | 1 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 90 | 90 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 50 | |

| 12 | 41 | F | 4 | 6 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 60 | 60 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 60 | Improvement in open pores |

| 13 | 35 | F | 4 | 10 | Yes (4–7) | Yes (1–3) | 50 | 40 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 22 | 6 | 16 | 80 | Improvement in open pores |

| 14 | 44 | F | 4 | 7 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 70 | 40 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 60 | |

| 15 | 27 | F | 4 | 6 | Yes (1–3) | No | 70 | 60 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 12 | 10 | 50 | |

| 16 | 27 | F | 4 | 7 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 80 | 80 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 8 | 50 | |

| 17 | 19 | M | 4 | 1 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 70 | 70 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 27 | 6 | 21 | 70 | |

| 18 | 28 | F | 4 | 5 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 50 | 60 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 12 | 10 | 70 | |

| 19 | 27 | F | 4 | 6 | Yes (1–3) | No | 90 | 90 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 60 | Improvement in sebaceous hyperplasia & pores |

| 20 | 49 | M | 4 | 5 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 70 | 70 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 19 | 9 | 10 | 70 | |

| 21 | 28 | F | 4 | 4 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 70 | 80 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 60 | |

| 22 | 28 | M | 4 | 8 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 60 | 50 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 60 | |

| 23 | 28 | F | 4 | 7 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 30 | 30 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 21 | 9 | 12 | 50 | |

| 24 | 27 | F | 4 | 6 | Yes (4–7) | No | 40 | 40 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 9 | 13 | 40 | Improvement in open pores |

| 25 | 24 | M | 4 | 5 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 60 | 30 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 27 | 18 | 9 | 80 | |

| 26 | 30 | F | 4 | 4 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 80 | 80 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 21 | 12 | 9 | 70 | |

| 27 | 24 | M | 4 | 5 | Yes (1–3) | No | 60 | 70 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 60 | |

| 28 | 31 | M | 4 | 1 | Yes (1–3) | No | 80 | 90 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 27 | 18 | 9 | 60 | |

| 29 | 29 | M | 4 | 6 | Yes (1–3) | No | 60 | 70 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 50 | |

| 30 | 26 | M | 4 | 5 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 60 | 60 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 20 | 9 | 11 | 80 | |

| 31 | 32 | M | 4 | 4 | Yes (1–3) | Yes (1–3) | 60 | 70 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 18 | 9 | 9 | 40 | |

| 32 | 28 | F | 4 | 5 | Yes (1–3) | No | 50 | 40 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 9 | 13 | 40 |

Of the 32 patients, 62.5% were females and 37.5% were males. The patients age ranged from a minimum of 19 years to a maximum of 49 years with the average age of each subject 30.3 years [Table 7].

Table 7.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients

| Variable | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <20 | 1 | 3.125 |

| 20–29 | 16 | 50 | |

| 30–39 | 13 | 40.63 | |

| >40 | 2 | 6.25 | |

| Gender | Male | 12 | 37.5 |

| Female | 20 | 62.5 |

All patients were asked to grade the pain experienced during the treatment on a visual analogue scale of 1–10. On statistical analysis, it was found that the mean grade of the pain experienced by the patients was 5.34, the lowest being 1, and the highest being 10 with a standard deviation of 2.03.

All of the patients experienced redness after the treatment. For 81.3% of the patients, the redness lasted for 1–3 days whereas for 18.8% it lasted for 4–7 days. In total, 75% of the patients experienced swelling after the treatment that lasted from 1 to 3 days for 71.9% and 4 to 7 days for 3.1% of the patients.

Few patients experienced more spot bleeding then usual especially those who were treated with isotretinoin and other modalities like dermaroller or CO2 laser in the past. No other subsequent adverse effects were reported. One of the patients discontinued treatment after the first session due to appearance of shoe marks which gradually resolved after few months [Figure 4]. No infections, postinflammatory pigmentation, and scarring were reported post treatment.

Figure 4.

Shoe marks after first session

Evaluation of treatment results

Subjective analysis

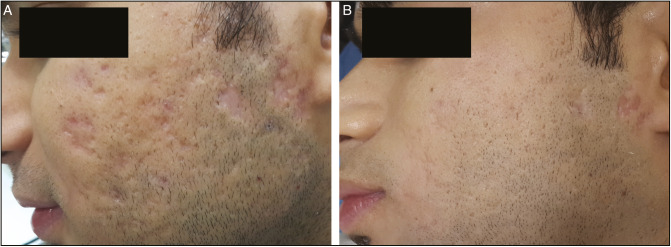

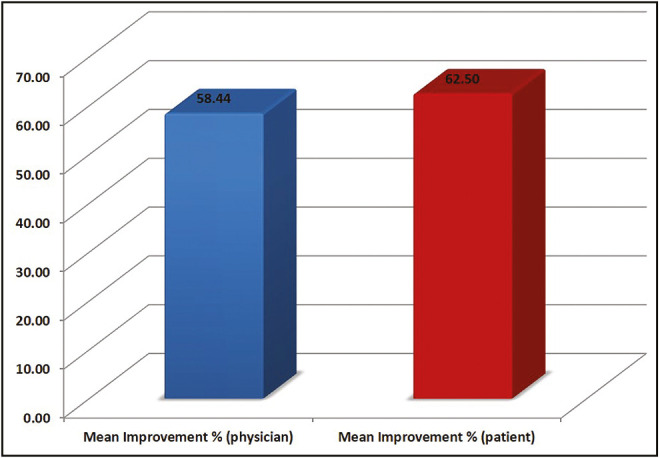

All of the patients enrolled in the study experienced improvement in their acne scars after four sessions of the treatment. The percentage improvement as experienced by the patient ranged from a minimum of 30% to a maximum of 90% [Figures 5–7]. The mean improvement experienced by the patients was found to be 62.50% with a standard deviation of 16.06 [Figure 8].

Figure 5.

Excellent improvement in 25-year-old man (A) before and (B) after four sessions

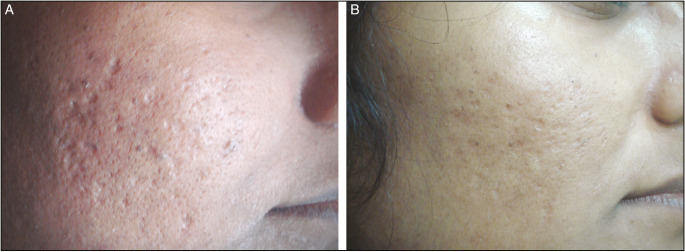

Figure 7.

Significant clinical improvement in atrophic acne scars and large facial pores in a 27-year-old woman before (A) and after (B) four sessions

Figure 8.

Percentage overall improvement

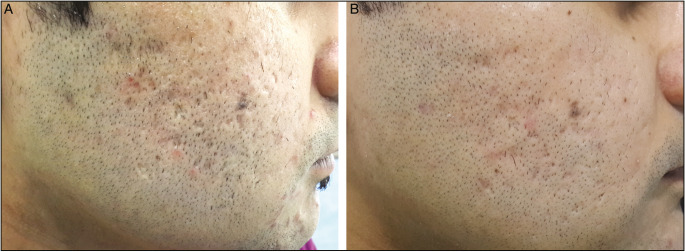

Figure 6.

Outstanding improvement in acne scars in a 28-year-old man before (A) and 6 months after (B) four sessions

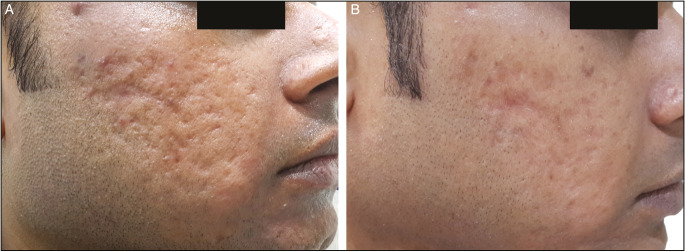

Another therapeutic benefit experienced by the patients was the improvement in the skin tightening [Figure 9] that ranged from 30% to 90% with an average of 61.88% and standard deviation of 20.23 [Figure 10].

Figure 9.

Remarkable improvement in acne scars and skin tightening in a 34-year-old man before (A) and after (B) four sessions

Figure 10.

Percentage skin tightening

Objective analysis

The objective analysis of the treatment results was done on three scales.

(A) The global Investigator’s assessment

On analyzing the improvement in the acne scars using the Global investigator’s assessment score, it was found that the improvement ranged from 40% to 80% with a mean of 58.44% and Standard Deviation of 12.47.

The mean improvement % was compared between physician and patient using the paired t test. No significant difference was observed in mean improvement % between physician and patient [Table 8].

Table 8.

Comparison of mean improvement

| Mean | Std. deviation | Mean difference | t test value | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement % (physician) | 58.44 | 12.47 | -4.06 | -1.336 | 0.191 |

| Improvement % (patient) | 62.50 | 16.06 |

Paired t test

# Nonsignificant difference

The correlation of improvement % between physician and patient was done using the Pearson’s correlation test [Figure 11]. There was no significant correlation of improvement % of physician with patient [Table 9].

Figure 11.

Mean percentage improvement

Table 9.

Correlation of improvement percentage

| N | Correlation | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement % (physician) and Improvement % (patient) | 32 | 0.294 | 0.103 |

Pearson’s correlation test

# Nonsignificant difference

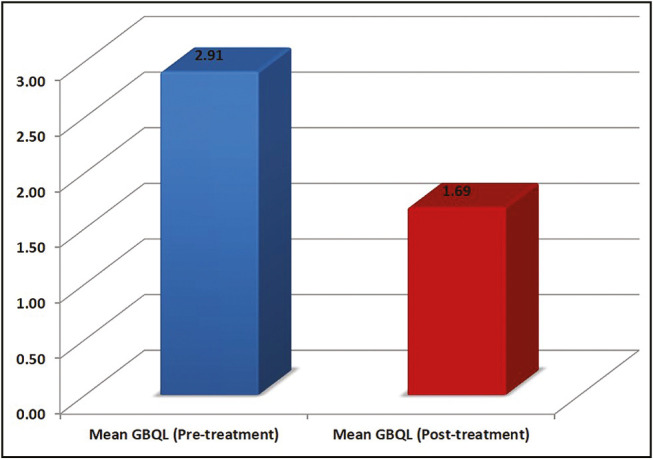

(B) Goodman and Baron’s Qualitative (GBQL) Score

On analyzing the acne scars before treatment with Goodman and Baron’s Qualitative grade, it was found that the mean grade was 2.91 which reduced to 1.69 after treatment. The average difference in the grading was found to be 1.22 between the pretreatment and posttreatment scores.

The mean GBQL score was compared pre- and posttreatment using the Wilcoxon-sign rank test [Figure 12]. The mean GBQL score decreased significantly from pre- to posttreatment [Table 10].

Figure 12.

Mean GBQL score

Table 10.

Comparison of mean GBQL score

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. deviation | t test value | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBQL (pretreatment) | 2 | 4 | 2.91 | 0.64 | 16.414 | <0.001* |

| GBQL (posttreatment) | 1 | 2 | 1.69 | 0.47 | ||

| GBQL difference | 1 | 2 | 1.22 | 0.42 |

Wilcoxon-sign rank test

*Significant difference

The distribution of GBQL score pre- and posttreatment were compared using the chi-square test [Table 11]. There was a significant difference between GBQL score pre- and posttreatment. Scores 1 and 2 increased significantly from pre- to posttreatment [Figure 13].

Table 11.

Comparison of GBQL pre- and posttreatment

| GBQL (pretreatment) | GBQL (posttreatment) | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Frequency | |

| 1 | 0 | 10 |

| 0.0% | 31.3% | |

| 2 | 8 | 22 |

| 25.0% | 68.8% | |

| 3 | 19 | 0 |

| 59.4% | 0.0% | |

| 4 | 5 | 0 |

| 15.6% | 0.0% | |

| Total | 32 | 32 |

| 100.0% | 100.0% |

Chi-square value = 23.671

P Value < 0.001*

Figure 13.

GBQL score pre- and posttreatment

The correlation of GBQL score was done between pre- and posttreatment using the Spearman’s correlation test. There was a significant correlation of GBQL score of pre- with posttreatment [Table 12].

Table 12.

Correlation of GBQL pre- and posttreatment

| N | Correlation | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBQL (pretreatment) and GBQL (posttreatment) | 32 | 0.755 | <0.001* |

Spearman’s correlation test

*Significant difference

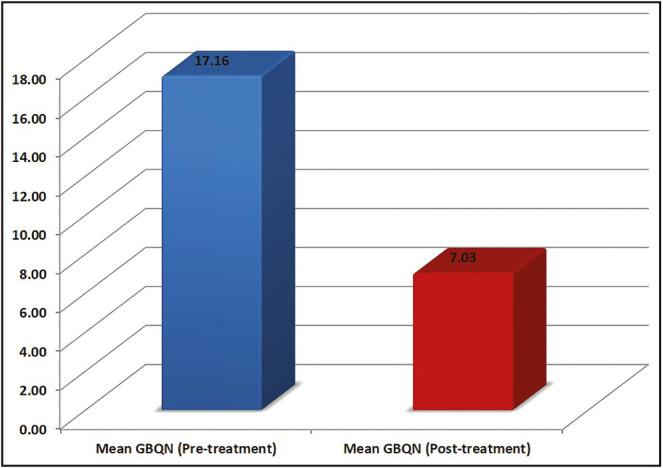

(C) Goodman and Baron’s Quantitative (GBQN) Score

On analyzing the acne scars before treatment with Goodman and Baron’s Quantitative scoring, it was found that the mean score was 17.16 which reduced to 7.03 after treatment [Figure 14]. The average difference in the grading was found to be 10.13 between the pretreatment and posttreatment scores.

Figure 14.

Mean GBQN score

The mean GBQN score was compared pre- and posttreatment using the paired t test. The mean GBQN score decreased significantly from pre- to posttreatment [Table 13].

Table 13.

Comparison of mean GBQN

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. deviation | t test value | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBQN (pretreatment) | 9 | 27 | 17.16 | 6.10 | 14.975 | <0.001* |

| GBQN (posttreatment) | 3 | 18 | 7.03 | 4.37 | ||

| GBQN difference | 6 | 21 | 10.13 | 3.82 |

Paired t test

*Significant difference

The correlation of GBQN score was done between pre- and posttreatment using the Pearson’s correlation test. There was a significant correlation of GBQN score of pre- with posttreatment [Table 14].

Table 14.

Correlation of GBQN pre- and posttreatment

| N | Correlation | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBQN (pretreatment) and GBQN (posttreatment) | 32 | 0.781 | <0.001* |

Pearson’s correlation test

*Significant difference

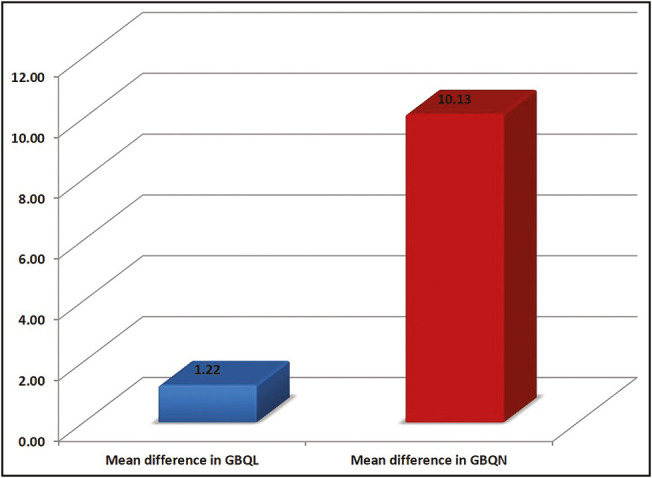

The mean difference in GBQL and GBQN score was compared using the Wilcoxon-sign rank test [Figure 15]. The mean difference in GBQN score was significantly more than GBQL score [Table 15].

Figure 15.

Mean difference in GBQL and GBQN score

Table 15.

Comparison of mean difference in GBQL and GBQN scores

| Mean | Std. deviation | Mean difference | t test value | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBQL difference | 1.22 | 0.42 | -8.91 | –13.808 | <0.001* |

| GBQN difference | 10.13 | 3.82 |

Wilcoxon-sign rank test

*Significant difference

The correlation of mean difference in GBQL score was done with mean difference in GBQN score using the Spearman’s correlation test. There was a significant correlation of mean difference in GBQL score with mean difference in GBQN score [Table 16].

Table 16.

Correlation of mean difference in GBQL and GBQN scores

| N | Correlation | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBQL difference and GBQN difference | 32 | 0.464 | 0.007* |

Spearman’s correlation test

*Significant difference

DISCUSSION

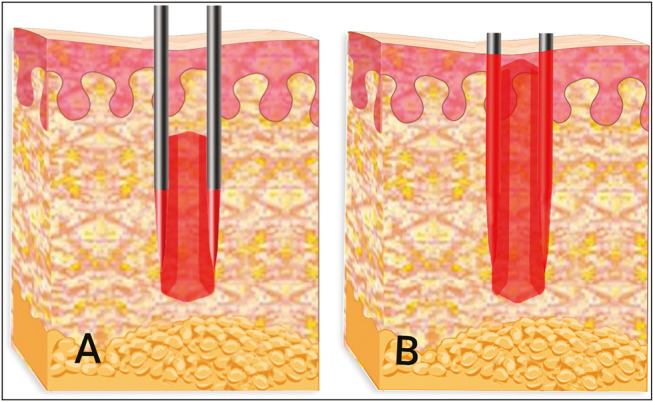

The fractional MNRF system used in the study delivers both monopolar and bipolar RF energy through array of insulated microneedles. In insulated needle, the microneedle electrodes are nonconductive except for the 0.3 mm from the distal end. As the insulated microneedles emit RF energy only from the tip, it has an advantage of no electrothermal damage to the epidermis as compared to the noninsulated needles [Figure 16].

Figure 16.

Insulated (A) and noninsulated needles (B) emitting bipolar RF. Note that epidermis is spared in insulated needles

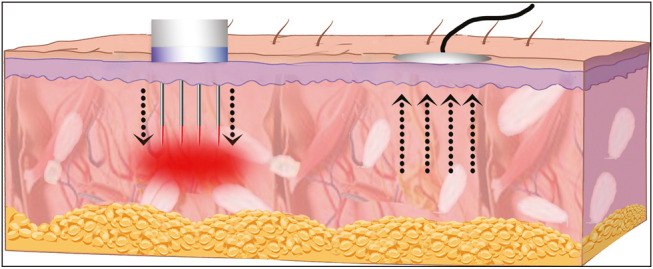

In bipolar radiofrequency, energy is conducted between the alternating rows of positive and negative electrode pins. As the zone of necrosis is confined to the tip of electrodes, bipolar radiofrequency is very effective in treating scars. On the contrary, in monopolar RF, energy is conducted between electrodes and the grounding plate [Figure 17]. As the RF energy flows deep and diffuse in the reticular dermis, monopolar RF is very beneficial in skin tightening and lifting as well.[21]

Figure 17.

Insulated needles emitting monopolar RF

In this study, insulated needles emitting both bipolar and monopolar RF were used in a unique method of treatment. The varying depth rotational stamping technique with bipolar RF ensured that the entire depth of each scar is treated, whereas the criss-cross method using monopolar RF corroborates the delivery of radiofrequency waves to all the scars and deeper reticular dermis. With this approach, it is possible to heat the deeper tissues adequately, leading to greater collagen remodeling, contraction, and stimulation without damaging epidermis.

Ramesh et al.[22] treated facial acne scars of 30 subjects with a matrix tunable radiofrequency device. The visual analog scale of improvement in scars ranged from 10%–50% at end of 2 months to 20%–70% at the end of 6 months. Gold et al.[23] conducted a study wherein 13 patients with mild-to-moderate acne scars were treated with bipolar fractional radiofrequency. Approximately 67%–92% patients were satisfied with the results. Cho et al.[16] evaluated efficacy of fractional radiofrequency in treatment of 30 patients with mild-to-moderate acne scars and large facial pores with improvement in more than 70% of the patients. Despite these differences, all studies show that fractional radiofrequency is both safe and effective for the treatment of acne scars.

In our study, all patients showed a significant improvement in acne scars, texture, and pigmentation with high degree of satisfaction. Most of the patients started noticing clinical improvement in 4–6 weeks after first session [Figure 18]. After four treatments, all subjects rated themselves as having at least 30%–90% (mean––62.50%) improvement in acne scars, whereas unbiased physicians graded 40%–80% (mean––58.44%) improvement in scar conditions at a 6-month follow-up visit. As the long-term dermal remodeling continues for months after the last session, most of the patients observed improvement in the scars 6 months to 1 year after completion of the treatment.

Figure 18.

Clinical improvement in acne scars before (A) and three after (B) three sessions

In addition, all patients reported 30%–90% (mean––61.88%) improvement in facial contour and skin tightening. MNRF has been reported to improve skin laxity and wrinkles.[24,25] In a study conducted by Lee et al.,[26] who tested a fractional bipolar RF system on 26 Korean women, they found significant incremental improvements in smoothness and tightness 6 weeks after the third session from baseline. More pronounced smoothness and skin tightening in our study could be attributed to dual effect of both monopolar and bipolar RF. Monopolar radiofrequency has been reported to induce profound neoelastogenesis and neocollagenesis in the deep dermis, which has been suggested as a potential mechanism of clinical efficacy.[15,21]

Many patients noticed improvement in the open pores. It has been suggested that changes in facial pores may be attributed to dermal remodeling and decline in sebum production.[27]

Most of the studies are done with noninsulated microneedling RF and reported side effects are eschar, blister, downtime, and PIH. One of the major concerns in treating Asians with ablative lasers is the development of PIH. Wosyet Vital technique is a novel approach that helped in achieving greater improvement in the scars and skin tightening while reducing patient’s discomfort and down time. Compared with noninsulated MNRF and ablative lasers, the major advantage of this technique is that it can be used to treat scars in all skin types with negligible risk of PIH. We did not find PIH after this technique in Asian patients with acne scars despite of more aggressive treatment parameters and several treatment sessions.

Another important characteristic that makes this study unique is the fact that all subjects enrolled in the study paid for their treatment. This commercial aspect helped eliminating bias that may have occurred in assessing the efficacy and patient satisfaction in nonpaid patients.

One of the major limitations of this self-controlled single arm study was the lack of control arm and direct comparison between available MNRF devices with noninsulated needles and other existing treatment modalities for acne scars such as fractional lasers. Further randomized controlled trials are essential to compare this unique method of treatment with other available modalities for acne scar management.

We declare that none of the authors have any financial, professional, and personal interests of any kind with other people, companies or organizations that can inappropriately influence the quality of the work presented in this manuscript.

CONCLUSION

Till date, there has been no study on MNRF using such technique for the treatment of acne scars. Wosyet Vital technique using multiple depth rotational stamping and monopolar criss-cross method with insulated needles is found to be safe and efficacious in managing acne scars in the Asians.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, Hill K, Eaton SB, Brand-Miller J. Acne vulgaris: A disease of western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1584–90. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.12.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:246–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18131897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharquie K, Al-Hamdi K, Noaimi AA, AlBattat R. Scarring & no scarring facial acne vulgaris & frequency of associated skin disease. Iraqi Postgrad Med J. 2009;8:332–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orentreich DS, Orentreich N. Subcutaneous incisionless (subcision) surgery for the correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:543–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkhawam L, Alam M. Dermabrasion and microdermabrasion. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25:301–10. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beer K. A single-center, open-label study on the use of injectable poly- L -lactic acid for the treatment of moderate to severe scarring from acne or varicella. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:S159–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabbrocini G, Annunziata MC, D’Arco V, De Vita V, Lodi G, Mauriello MC, et al. Acne scars: Pathogenesis, classification and treatment. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:893080. doi: 10.1155/2010/893080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grevelink JM, White VR. Concurrent use of laser skin resurfacing and punch excision in the treatment of facial acne scarring. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:527–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manuskiatti W, Triwongwaranat D, Varothai S, Eimpunth S, Wanitphakdeedecha R. Efficacy and safety of a carbon-dioxide ablative fractional resurfacing device for treatment of atrophic acne scars in Asians. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:274–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu S, Chen MC, Lee MC, Yang LC, Keoprasom N. Fractional resurfacing for the treatment of atrophic facial acne scars in Asian skin. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:826–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahmoud BH, Srivastava D, Janiga JJ, Yang JJ, Lim HW, Ozog DM. Safety and efficacy of erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet fractionated laser for treatment of acne scars in type IV to VI skin. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:602–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoo KH, Ahn JY, Kim JY, Li K, Seo SJ, Hong CK. The use of 1540 nm fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of acne scars in Asian skin: A pilot study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2009;25:138–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2009.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jih MH, Kimyai-Asadi A. Fractional photothermolysis: A review and update. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hantash BM, Renton B, Berkowitz RL, Stridde BC, Newman J. Pilot clinical study of a novel minimally invasive bipolar microneedle radiofrequency device. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41:87–95. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hantash BM, Ubeid AA, Chang H, Kafi R, Renton B. Bipolar fractional radiofrequency treatment induces neoelastogenesis and neocollagenesis. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41:1–9. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho SI, Chung BY, Choi MG, Baek JH, Cho HJ, Park CW, et al. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy of fractional radiofrequency microneedle treatment in acne scars and large facial pores. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1017–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson JD, Palm MD, Kiripolsky MG, Guiha IC, Goldman MP. Evaluation of the effect of fractional laser with radiofrequency and fractionated radiofrequency on the improvement of acne scars. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1260–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vejjabhinanta R, Wanitphakdeedecha P, Limtanyakul, Manuskiatti W. The efficacy in treatment of facial atrophic acne scars in Asians with a fractional radiofrequency microneedle system. J EUR Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1219–25. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: A qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring–a quantitative global scarring grading system. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2006.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lolis MS, Goldberg DJ. Radiofrequency in cosmetic dermatology: A review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1765–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramesh M, Gopal M, Kumar S, Talwar A. Novel technology in the treatment of acne scars: The matrix-tunable radiofrequency technology. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3:97–101. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.69021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold MH, Biron JA. Treatment of acne scars by fractional bipolar radiofrequency energy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012;14:172–8. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2012.687824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexiades-Armenakas M, Rosenberg D, Renton B, Dover J, Arndt K. Blinded, randomized, quantitative grading comparison of minimally invasive, fractional radiofrequency and surgical face-lift to treat skin laxity. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:396–405. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hruza G, Taub AF, Collier SL, Mulholland SR. Skin rejuvenation and wrinkle reduction using a fractional radiofrequency system. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:259–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee HS, Lee DH, Won CH, Chang HW, Kwon HH, Kim KH, et al. Fractional rejuvenation using a novel bipolar radiofrequency system in Asian skin. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1611–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uhoda E, Piérard-Franchimont C, Petit L, Piérard GE. The conundrum of skin pores in dermocosmetology. Dermatology. 2005;210:3–7. doi: 10.1159/000081474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]