Abstract

Background

Implementation of the Accelerate PhenoTM Gram-negative platform (RDT) paired with antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) intervention projects to improve time to institutional-preferred antimicrobial therapy (IPT) for Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) bloodstream infections (BSIs). However, few data describe the impact of discrepant RDT results from standard of care (SOC) methods on antimicrobial prescribing.

Methods

A single-center, pre-/post-intervention study of consecutive, nonduplicate blood cultures for adult inpatients with GNB BSI following combined RDT + ASP intervention was performed. The primary outcome was time to IPT. An a priori definition of IPT was utilized to limit bias and to allow for an assessment of the impact of discrepant RDT results with the SOC reference standard.

Results

Five hundred fourteen patients (PRE 264; POST 250) were included. Median time to antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) results decreased 29.4 hours (P < .001) post-intervention, and median time to IPT was reduced by 21.2 hours (P < .001). Utilization (days of therapy [DOTs]/1000 days present) of broad-spectrum agents decreased (PRE 655.2 vs POST 585.8; P = .043) and narrow-spectrum beta-lactams increased (69.1 vs 141.7; P < .001). Discrepant results occurred in 69/250 (28%) post-intervention episodes, resulting in incorrect ASP recommendations in 10/69 (14%). No differences in clinical outcomes were observed.

Conclusions

While implementation of a phenotypic RDT + ASP can improve time to IPT, close coordination with Clinical Microbiology and continued ASP follow up are needed to optimize therapy. Although uncommon, the potential for erroneous ASP recommendations to de-escalate to inactive therapy following RDT results warrants further investigation.

Keywords: antimicrobial stewardship, rapid diagnostics, bloodstream infections, susceptibility testing

Implementation of a rapid phenotypic diagnostic test, plus antimicrobial stewardship intervention for Gram-negative bloodstream infections, was associated with significantly faster time to institutional preferred therapy without change in clinical outcomes. Occasional erroneous results contributed to incorrect ASP recommendations.

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) with Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) are associated with significant mortality, with delay in active therapy associated with worsened prognosis [1–3]. Administration of timely active therapy has been further complicated by increasing rates of antimicrobial resistance [4], along with increasing recognition of the need to avoid overuse of broad-spectrum agents [5, 6]. Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) have emerged as a promising tool in targeting appropriate therapy to patients earlier, and when paired with an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) have been associated with improved outcomes, including mortality [7].

Until recently, rapid diagnostics for GNB BSIs have primarily utilized genotypic approaches that provide rapid identification with limited resistance targets [8, 9]. However, the complexity of Gram-negative resistance mechanisms limits the ability of these methods to effectively support modification to definitive therapy. As broad-spectrum empiric therapies are often prescribed, early phenotypic susceptibility information is not only needed to guide timely active therapy, but also help drive prompt elimination of unnecessary antimicrobial spectrum, a fundamental goal of any ASP [5].

The Accelerate PhenoTM system (Accelerate Diagnostics, Tucson, AZ) is a novel RDT which uses fluorescence in-situ hybridization for rapid species identification (ID) and morphokinetic bacterial analysis for phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) within 7 hours of a positive blood culture result [10]. Recent studies have shown improved time to first antimicrobial change [11] and optimal antimicrobial therapy [12, 13] when employing the Accelerate PhenoTM system in combination with an ASP intervention for GNB BSI. However, outside of improvement in length of stay (LOS) in one study [12], little change in clinical outcomes has been observed. Though previous studies show favorable concordance with conventional methods [10, 14], there has been limited evaluation of the potential for harm when discordance does occur.

We hypothesized that implementation of a paired phenotypic RDT + ASP intervention at our institution would result in improved time to institutional-preferred therapy (IPT) and clinical outcomes for GNB BSIs with a decrease in overall unnecessary antimicrobial spectrum exposure. In addition, as conventional methods continued to be employed in tandem with the RDT during the intervention, we sought to evaluate the impact of discrepant RDT results on ASP intervention and ultimate prescribing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting and Participants

A pre-/post-intervention, quasi-experimental study was performed at a 619-bed tertiary care hospital (University of Virginia (UVA) Medical Center, Charlottesville, VA). Patients ≥ 18 years of age were evaluated for study inclusion by querying the institution’s database for blood culture Gram stain results positive for GNB only between July 2017 and July 2019. Only the first positive culture for each patient was included during the entire study period. Exclusion criteria included: 1) no GNB ultimately isolated; 2) non-inpatient status at time of Gram stain result; or 3) discharge, death, or initiation of comfort-measures only within 24 hours of Gram stain result. Patients were divided into 2 cohorts: a historical period (PRE; July 1, 2017 to July 11, 2018) and an intervention period (POST; July 12, 2018 to July 11, 2019) following implementation of the Accelerate PhenoTM system (RDT). The institutional ASP operating during both periods consisted of infectious diseases-trained pharmacists and physicians. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences Research at the University of Virginia (IRB #21369; #18393).

Historical Period

During both periods, a standard Gram stain was performed on blood cultures that alerted positive from BacT/Alert® 3D (bioMérieux, Durham, NC) and the treating team was notified. During the historical period, ID and AST were performed using VITEK® MS and VITEK®2 AST-GN70 (BioMerieux, Durham, NC) from growth on solid media through April 14, 2018 when the susceptibility platform was changed to lyophilized SensititreTM GN6F (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). This change in platform was largely implemented so that current Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) systemic treatment breakpoints for cefazolin could be used [15]. Results were verified and released directly into the electronic medical record (EMR) typically 7 AM–3:30 PM, 7 days a week. ID with or without AST results were released in real-time via email alert to ID-trained pharmacist members of the ASP via TheraDoc (Premier, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT) and reviewed during business hours, 5 days a week for potential optimization.

Intervention Period

During the intervention period, the first positive blood culture showing GNB (index culture) was processed via RDT. Index and companion cultures were concurrently evaluated using SOC methods as detailed above. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for all methods including RDT were interpreted using CLSI breakpoints [16], including release of non-FDA cleared cefazolin when susceptible. To minimize errors, during RDT validation several local rules were established for routine suppression of results which are detailed in the Supplementary Methods. The RDT was operated 24/7, and full ID and AST results were e-mailed in real-time to the ASP following run completion.

Upon review of RDT results and EMR, ASP team members communicated to clinical microbiology personnel whether to release full, partial, or none of the RDT susceptibility interpretation results into the EMR. Results outside of business hours were reviewed at the discretion of the covering ASP member, but could not be released to the EMR until the following morning. Following review, recommendations were communicated with the treating team via phone discussion and implemented at the discretion of the provider. Once SOC methods were complete, the ASP was notified of categorical disagreement in comparison to the RDT; the treating team was then notified and the EMR updated to reflect the SOC AST results.

Data Collection and Definitions

Baseline and outcomes data were collected retrospectively from the institution’s central data repository. Antimicrobial administration, microbiologic and clinical data were further extracted during review of the EMR. Comorbidity burden was estimated by the Charlson Comorbidity Index [17] and baseline severity of BSI by the Pitt bacteremia score [18]. BSI sources were defined according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria [19, 20]. Antimicrobial days of therapy (DOTs) were collected for all antibacterial agents administered during the eight inpatient days post-culture collection. On-formulary agents were grouped according to CDC Standardized Antimicrobial Administration Ratio (SAAR) categories [21].

Active therapy was defined as administration of a susceptible agent based on the SOC method. IPT was defined as the narrowest susceptible formulary beta-lactam based on SOC results as follows (beginning with narrowest spectrum): 1) cefazolin or ampicillin–sulbactam, 2) ceftriaxone, 3) cefepime or piperacillin–tazobactam, or 4) carbapenem; further exceptions are detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

ASP recommendations were collected from prospectively recorded case e-mail documentation, and acceptance was evaluated by review of the EMR for order entry within 24 hours of RDT completion. RDT results were deemed to be discrepant from SOC (considered the reference standard) in the following situations: 1) RDT provided no/incorrect ID for on-panel organisms, 2) RDT ID without AST results, 3) a polymicrobial specimen was missed, or 4) disagreement in designation of IPT as follows: when the agent deemed IPT by SOC was not susceptible (intermediate or resistant) on RDT this was characterized as “false resistance.” Conversely, “false susceptible” was assigned when a narrower-spectrum agent than the agent deemed IPT by SOC was found to be susceptible by RDT. Prescribing outcomes following discrepant results were reviewed and categorized as 1) no impact, 2) continuation of unnecessary broad therapy, 3) erroneous escalation, or 4) de-escalation to inactive therapy (see Supplementary Methods).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was time to IPT, defined as time elapsed between index culture collection and first administration of an antimicrobial agent meeting the IPT definition.

Secondary outcomes for both groups included: in-hospital and 30-day mortality, total and post-Gram stain LOS, ICU LOS post-Gram stain, 30-day readmission, BSI relapse within 30 days of therapy completion, Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) within 90 days of BSI, discharge disposition, antimicrobial utilization (DOTs), and timing of microbiology results.

For the intervention group, the following were also evaluated: concordance of RDT and SOC methods, ASP intervention type and acceptance, and prescribing outcomes of discrepant results.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using statistical software R, version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) [22]. For categorical data, Pearson χ 2 and Fisher’s exact test were used as appropriate. For continuous data, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used. Kaplan Meier analysis was performed to assess time to IPT. Patients who were discharged or deceased prior to receiving IPT were censored at that time. Log-rank P value was reported to evaluate statistical significance between groups in reaching IPT over the analysis time period. A quasi-Poisson regression was used to compare rates of antimicrobial utilization between groups, using days present as an offset. P values ≤ .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient and Microbiologic Characteristics

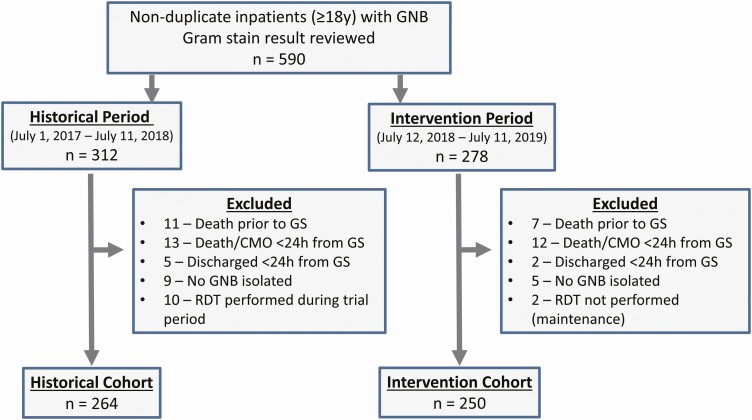

A total of 590 unique patients with GNB-BSI were evaluated, with 264 during the historical period and 250 during the intervention period meeting inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Patient demographics, comorbidities, and clinical characteristics were similar between groups (Table 1), with the exception of moderate/severe chronic kidney disease and severe neutropenia being more prevalent in the historical group, and mechanical ventilation being more prevalent in the intervention group. BSI episode onset, source, organisms involved, and resistance characteristics were similar between groups (Table 2), with the exception of more catheter-associated infections and episodes involving Serratia marcescens in the historical period, and more episodes involving Escherichia coli in the intervention period.

Figure 1.

Included study participants. Abbreviations: GNB, Gram-negative bacilli; GS, Gram stain result; RDT, rapid diagnostic test.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Historical, n = 264a | Intervention, n = 250a | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 64 (53, 73) | 64 (55, 75) | .64 |

| Male sex | 148 (56) | 129 (52) | .35 |

| Race or ethnic group | |||

| White | 205 (78) | 187 (75) | .51 |

| Black | 50 (19) | 48 (19) | >.99 |

| Hispanic | 9 (3) | 12 (5) | .57 |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | .11 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 4 (2, 7) | 3.5 (2, 7) | .18 |

| Myocardial infarction | 37 (14) | 29 (12) | .49 |

| Congestive heart failure | 64 (24) | 61 (24) | >.99 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 37 (14) | 25 (10) | .21 |

| Dementia | 21 (8.0) | 13 (5.2) | .28 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 70 (27) | 57 (23) | .38 |

| Liver disease, moderate or severe | 21 (8.0) | 23 (9.2) | .73 |

| Diabetes mellitus, with or without complications | 107 (41) | 112 (45) | .37 |

| Kidney disease, moderate/severe chronic | 100 (38) | 71 (28) | .03 |

| ESRD requiring dialysis | 18 (6.8) | 16 (6.4) | .99 |

| Immunosuppression | |||

| Solid tumor | 56 (21) | 70 (28) | .09 |

| Leukemia or lymphoma | 24 (9.1) | 14 (5.6) | .18 |

| Chemotherapy (within past 6 months) | 63 (24) | 48 (19) | .24 |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplant | 19 (7.2) | 8 (3.2) | .07 |

| Solid organ transplant | 22 (8.3) | 27 (11) | .42 |

| AIDS | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | >.99 |

| Clinical Status | |||

| Pitt bacteremia score | 2 (0, 3) | 2 (0, 3) | .76 |

| Vasopressors | 58 (22) | 61 (24) | .58 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 27 (10) | 41 (16) | .05 |

| Severe neutropenia (ANC < 500) | 39 (15) | 22 (8.8) | .05 |

| ICU Admission (at time of Gram stain) | 79 (30) | 88 (35) | .24 |

| Primary Service | .06 | ||

| Medical | 213 (81) | 183 (73) | |

| Surgical | 51 (19) | 67 (27) | |

| ID consultc (prior to Gram stain) | 50 (19) | 46 (18) | .97 |

Bold data indicate statistical significance (P value ≤ .05).

Abbreviations: ANC, absolute neutrophil count; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; ICU, intensive care unit; ID, infectious disease; IQR, interquartile range.

aStatistics presented: median (IQR); n (%)

bStatistical tests performed: Wilcoxon rank-sum test; chi-square test of independence; Fisher’s exact test

cIncludes Infectious Disease attending physician on General Medicine service.

Table 2.

Baseline Microbiologic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Historical, n = 264a | Intervention, n = 250a | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community-onsetc | 172 (65) | 181 (72) | .09 |

| Polymicrobial episode | 25 (9.5) | 28 (11) | .62 |

| Received active therapy before Gram stain result | 204 (78) | 210 (84) | .07 |

| Source | |||

| Urinary | 104 (39) | 106 (42) | .55 |

| GI Tract | 50 (19) | 55 (22) | .45 |

| Catheter-associated | 36 (14) | 16 (6) | .01 |

| Biliary | 32 (12) | 32 (13) | .92 |

| Respiratory | 29 (11) | 15 (6) | .06 |

| SSTI | 8 (3) | 17 (7) | .08 |

| Otherd | 5 (2) | 9 (3.6) | .36 |

| Episode organisms | |||

| Escherichia coli | 90 (34) | 111 (44) | .03 |

| Klebsiella species | 58 (22) | 55 (22) | >.99 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 24 (9) | 14 (6) | .18 |

| Enterobacter species | 22 (8) | 23 (9) | .85 |

| Serratia marcescens | 21 (8) | 8 (3) | .03 |

| Proteus species | 10 (4) | 11 (4) | .90 |

| Citrobacter species | 8 (3) | 3 (1) | .17 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | .61 |

| Off-panel organism onlye | 38 (14) | 34 (14) | .89 |

| Antimicrobial susceptibility f | |||

| Ampicillin-susceptible E. coli | 43/90 (48) | 63/111 (58) | .26 |

| Cefazolin-susceptible Klebsiella species | 48/58 (83) | 36/55 (65) | .06 |

| 3rd generation nonsusceptible Enterobacteralesg | 25/209 (12) | 26/211 (12) | >.99 |

| Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteralesg | 1/209 (0.5) | 1/211 (0.5) | >.99 |

| Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 0/24 (0) | 1/14 (7) | .78 |

Bold data indicate statistical significance (P value ≤ .05).

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; SOC, standard of care; SSTI, skin and soft-tissue infections.

aStatistics presented: n (%)

bStatistical tests performed: chi-square test of independence; Fisher’s exact test

cBlood culture collected ≤ 48 hours of admission.

dIncludes musculoskeletal, endovascular, and central nervous system sources.

eFor full details of off-panel organism distribution, please refer to Supplementary Table 1.

fAs determined by SOC method.

gIncluded E. coli,Citrobacter species, Enterobacter species, Klebsiella species, Proteus species, and Serratia marcescens.

Time to IPT (Primary Outcome)

In total, 219/264 (83%) historical and 216/250 (86%) intervention episodes achieved IPT (P = .337). Time to IPT was significantly reduced from the historical to interventions periods (median [IQR] PRE 64.5 [27.8, 88.1] vs POST 43.3 [21.2, 69.2] hours; difference 21.2; P < .001). Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 2) demonstrated a significant increase in the cumulative proportion of patients achieving IPT in the intervention group over the observed time period (log-rank P value = .004).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (log-rank) between groups of time from blood culture collection to institutional-preferred therapy (IPT).

Performance of RDT

The RDT provided full ID and AST in 191/250 (76.4%) episodes. Correct identification was provided in 191/205 (93.2%) on-panel monomicrobial and 2/8 (25%) on-panel polymicrobial cultures. Among 2375 antimicrobial susceptibility tests performed using both RDT and SOC for on-panel isolates, there were 141 (6%) minor errors, 12 (0.6%) major errors, and 8 (4%) very major errors (Supplementary Table 2). Errors in beta-lactams accounted for 90% of total errors (n = 146/161). Errors specifically in Pseudomonas aeruginosa occurred in more than half the isolates tested with a 57% false resistant rate (20/35) for on-formulary beta-lactams tested (Supplementary Table 3).

Both periods were similar in terms of time to culture positivity and time to SOC AST results (Figure 3; Supplementary Table 4). Median time from blood culture collection to release of AST results for on-panel episodes was significantly improved following the intervention (PRE 61.0 [IQR 54.9, 67.2] vs POST 31.6 [23.4, 38.5) hours; difference 29.4; P < .001).

Figure 3.

Comparison of time from blood culture collection to microbiologic results for on-panel organisms. Abbreviations: EMR, results released to electronic medical record; RDT, rapid diagnostic test; SOC, standard of care methods.

ASP Interventions & Outcomes of Discrepant Results

ASP evaluation followed RDT in 235/250 (94%) cases (Supplementary Table 5) and full susceptibility results were released in the majority of episodes (82%). Escalation was recommended in 25 (11%) and accepted in all cases. Recommendations to de-escalate (82/235 [35%]) and for ID consultation (25/196 [14%]) were accepted in 70% and 64% of episodes, respectively.

During the intervention period, 69/250 (28%) episodes had a discrepancy between RDT and SOC methods in organism ID or IPT (Table 4). These included the RDT assessing a broader agent as IPT (false resistance, 9%), an inactive agent as IPT (false susceptible; 5%), no AST (5%), no ID (4%), incorrect ID (2%), and missed polymicrobial (2%). A prescribing impact occurred in 55% of these cases, where unnecessarily broad therapy was continued most often. Erroneous escalation (7%) and de-escalation to inactive therapy (7%) occurred less frequently. In-hospital mortality occurred in 4 cases with discrepant results, none of which followed an inappropriate transition to inactive therapy.

Table 4.

Discrepant RDT Results and Outcomes (N = 69)

| Discrepancy Type | Continued Unnecessary Broad Therapy | Erroneous Escalation | De-escalation to Inactive Therapy | No Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | ||||

| No ID* (10) | 6 (60) | - | - | 4 (40) |

| Incorrect ID (6) | 3 (50) | - | - | 3 (50) |

| Missed polymicrobiala (6) | 1 (17) | - | 2 (33) | 3 (50) |

| Susceptibility | ||||

| False resistance (23) | 7 (30) | 5 (22) | - | 11 (48) |

| False susceptible (12) | 3 (25) | - | 3 (25) | 6 (50) |

| No AST result (12) | 8 (67) | - | - | 4 (33) |

| Total (69) | 28 (41) | 5 (7) | 5 (7) | 31 (45) |

Data presented as n (% of row).

Continued Unnecessary Broad Therapy: Proteus species (3); Escherichia coli (10); Klebsiella species (8); Enterobacter species (5); Serratia marcescens (1); Acinetobacter baumannii (1).

Erroneous Escalation: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (4); Serratia marcescens (1).

De-escalation to Inactive Therapy: Proteus species (2); Klebsiella species (1); Escherichia coli (1); Enterobacter species (1).

Abbreviations: AST, antimicrobial susceptibility; ID, identification; RDT, rapid diagnostic test.

aOn-panel organisms only.

Antimicrobial Utilization

Evaluation of antimicrobial DOTs/1000 days present over the 8 days post-culture collection (Table 3) revealed a significant decrease in broad-spectrum Gram-negative agents predominantly used for hospital-acquired infections (PRE 655.2 vs POST 585.8; P = .043) with a significant decrease in utilization of cefepime (PRE 265.0 vs POST 206.2; P = .008) amongst individual agents. An increase in use of narrow beta-lactams as a group was observed (PRE 69.1 vs POST 141.7; P < .001), with significant increases for ampicillin–sulbactam (PRE 15.0 vs. POST 48.1; P = .004) and ampicillin (PRE 7.5 vs POST 21.3; P = .049) as individual agents.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial Utilization (DOT per 1000 days present) Following Culture Collection (8 days)

| Characteristic | Historical, n = 264a | Intervention, n = 250a | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Gram-positive | 222.8 | 197.6 | .286 |

| Vancomycin | 218.7 | 183.1 | .120 |

| Daptomycin | 4.03 | 14.6 | .159 |

| Broad Gram-negative, hospital-acquired | 655.2 | 585.8 | .043 |

| Meropenem | 118.6 | 126.5 | .725 |

| Cefepime | 265.0 | 206.2 | .008 |

| Piperacillin––tazobactam | 226.3 | 236.0 | .729 |

| Aztreonam | 25.3 | 17.0 | .436 |

| Broad Gram-negative, community-acquired | 340.2 | 388.7 | .118 |

| Ceftriaxone | 230.3 | 256.1 | .349 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 110.0 | 132.6 | .237 |

| Narrow beta-lactam | 69.1 | 141.7 | <.001 |

| Cefazolin | 46.6 | 72.4 | .088 |

| Ampicillin–sulbactam | 15.0 | 48.1 | .004 |

| Ampicillin | 7.5 | 21.3 | .049 |

Bold data indicate statistical significance (P value ≤ .05).

Abbreviations: DOT, days of therapy; IQR, interquartile range.

aStatistics presented: median (IQR).

bStatistical tests performed: Quasi-Poisson Regression.

Clinical Outcomes

No significant differences in secondary clinical outcomes including in-hospital and 30-day mortality, LOS, CDI, readmission, or relapse of BSI were observed (Table 5). Fewer patients in the intervention group required outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) on discharge (PRE 12%; POST 5%, P = .009), while proportions of patients discharged to home, skilled-nursing facility (SNF), and hospice care were similar between groups.

Table 5.

Clinical Outcomes

| Characteristic | Historical, n = 264a | Intervention, n = 250a | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day mortality | 29 (11) | 26 (10) | .94 |

| In-hospital mortality | 17 (6.4) | 15 (6.0) | .98 |

| LOS (Total) | 8 (5–19) | 7 (5–17) | .43 |

| LOS (Post Gram stain) | 5 (3–12) | 6 (3–11) | .92 |

| ICU LOS (Post Gram stain)c | 4 (2–10) | 4 (2–7) | .66 |

| 30-day readmission | 65 (25) | 45 (18) | .09 |

| Relapse (30-day, same organism) | 9 (3.4) | 6 (2.4) | .68 |

| C. difficile infection (90-day) | 15 (5.7) | 14 (5.6) | >.99 |

| Discharge disposition | |||

| Home | 136 (52) | 134 (54) | .70 |

| SNF | 65 (25) | 74 (30) | .24 |

| Home w/ OPAT | 32 (12) | 13 (5) | .009 |

| Death | 19 (7) | 17 (7) | >.99 |

| Hospice | 12 (5) | 12 (5) | >.99 |

| Total duration of antimicrobial therapyd | 13 (9–15) | 12 (9–15) | .16 |

Bold data indicate statistical significance (P value ≤ .05).

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of stay; OPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy; SNF, skilled-nursing facility.

aStatistics presented: n (%); median (IQR).

bStatistical tests performed: chi-square test of independence; Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

cIncludes only patients who received ICU care post Gram stain.

dIncludes full duration of therapy received as an inpatient and outpatient.

DISCUSSION

Advances in clinical microbiologic testing promise to shorten the delay from suspicion of an infectious syndrome to actionable diagnostic results [23]. In the realm of BSIs, clinical impact has been most clearly demonstrated for Gram-positive organisms, especially Staphylococcus aureus, where RDTs have not only shortened time to preferred therapy, but also improved mortality [24]. Amongst GNB, the heterogeneity of both species involved and their resistance mechanisms limits the use of straightforward molecular targets [25]. Early phenotypic AST is therefore desirable, but minimizing the impact of error or incomplete results presents a challenge for any testing platform seeking to provide clinicians with early actionable information.

Our study is unique in that we utilized a formalized definition of IPT in attempt to limit bias in assessing achievement of optimal therapy. We found that the paired ASP + RDT intervention was associated with receiving IPT a median of 21.2 hours faster than during the historical period. This is similar to the 24.8 hour median difference in time to first antimicrobial change observed in the only RCT evaluation of the Accelerate PhenoTM system to date [11]. Other studies to date have assessed time to preferred therapy as defined by expert review and limited their evaluation to on-panel organisms. Another study noted a 43-hour decrease in time to optimal therapy for GNB with a longer historical comparison [12].

Given that a majority of patients were on active therapy prior to intervention (84%), de-escalation was the most common ASP-guided change in antimicrobial therapy (82/107, 77%). This led to a statistically significant decrease in broad-spectrum DOTs and an increase in narrow-spectrum beta-lactam usage during the observed time period. Though earlier de-escalation of broad-spectrum therapies has been associated with improved clinical outcomes for CDI [26, 27] and LOS [12], these were not observed in our study. Similar to other recent studies of the Accelerate PhenoTM system [11–13] we did not observe any difference in other clinical outcomes.

The adoption of an a priori IPT definition additionally allowed for a novel assessment of the impact of discrepant results between RDT and SOC methods on ASP interventions. While rates of minor and major errors were similar to previously described analyses [11], very major errors occurred at a higher than typically acceptable rate (4%) in the setting of a low overall number of resistant isolates [28, 29]. Taken together, in our cohort these resulted in 5 episodes where a patient was escalated to unnecessarily broad therapy, and 5 episodes of de-escalation to inactive therapy. Though these made up a small proportion of total cases (2% each), they resulted in 5/25 (20%) of ASP recommendations to escalate therapy being unnecessary and 5/82 (6%) of recommendations to de-escalate therapy being incorrect. We have found these instances can have ripple effects through a single center on the trust in ASP recommendations. One alternative, as pursued by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group (ARLG) [11], is to accept the more resistant method as reference when reporting susceptibility results. However, review of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in particular noted only a 63% categorical agreement between RDT and SOC methods (Supplementary Table 3). While as noted by the ARLG [11], the RDT generally yielded more resistant results, in our cohort this resulted in the RDT assessing a broader agent as IPT in 7/12 (58%) episodes, resulting in erroneous escalation in 4/12 (33%).

Several limitations of this study are important to note. First, this was a single-center study and our findings may not be applicable to institutions with differing patient populations, resistance rates, and laboratory/stewardship practices. While baseline characteristics were relatively well-balanced between the groups, a greater proportion of neutropenic patients in the historical period could have potentially contributed to delay in achieving IPT and increased the observed impact of the intervention. Similar to other prior studies, our study population did not exhibit high-rates of multi-drug resistant GNB, with the majority of patients receiving active empiric therapy prior to the intervention. Further differences in mortality or other clinical outcomes may be observed in settings with higher resistance rates. In addition, given the ASP was not available 24/7 and results required review prior to release, it is possible that earlier result availability could have led to earlier antimicrobial changes, though these measures were employed to limit action on potentially erroneous results. Importantly, the cost-effectiveness of implementing and maintaining these systems has yet to be analyzed, which was not within the scope of our study.

In summary, we demonstrate that implementation of a rapid phenotypic system for GNB BSIs was associated with improved ASP-guided time to institutional preferred therapy and incremental improvement in antimicrobial use, largely through earlier de-escalation. However, these differences did not translate to any measurable improvement in patient outcomes on top of current practices. In addition, we present evidence that use of the instrument is not without potential harm in the setting of incomplete or missing results, with extensive involvement of Clinical Microbiology and the ASP needed to reduce the number of discrepancies that impacted therapy. After careful review of these data, a multidisciplinary panel at our institution concluded that the modest gains in antimicrobial exposure without improvement in clinical outcomes did not justify the risk of uncommon, but potentially significant patient harm. The workgroup voted to discontinue use of this rapid diagnostic but advocated for continued prospective review of GNB BSIs by the ASP. As so much of ASP practice is based on trust in Clinical Microbiology results, we recommend that hospitals and ASPs carefully weigh the risks and benefits before adopting rapid susceptibility testing systems. Rapid diagnostics will be critical to improving antimicrobial prescribing practices, but continued close assessment of their performance and limitations will be needed to ensure optimal utilization.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Glossary

Nonstandard Abbreviations

- ASP

antimicrobial stewardship program

- ARLG

Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group

- AST

antimicrobial susceptibility testing

- BSI

bloodstream infections

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDI

Clostridioides difficile infection

- CLSI

Clinical and Laborataory Standards Institute

- DOT

days of therapy

- EMR

electronic medical record

- GNB

Gram-negative bacilli

- IPT

institutional-preferred antimicrobial therapy

- LOS

length of stay

- OPAT

outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy

- POST

intervention period

- PRE

historical period

- RDT

rapid diagnostic test

- SAAR

Standardized Antimicrobial Administration Ratio

- SNF

skilled-nursing facility

- SOC

standard of care.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (grant number 5T32-A1007046-43). Accelerate Diagnostics had no involvement in the study or manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest. A. J. M. has served as a consultant for Accelerate Diagnostics. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Prior presentation. A portion of this work was presented as an abstract/poster presentation for ID Week 2020. An earlier analysis of this work was presented as an abstract/poster at ASM Microbe 2019.

References

- 1.Kumar A, Ellis P, Arabi Y, et al. ; Cooperative Antimicrobial Therapy of Septic Shock Database Research Group . Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a five-fold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest 2009; 136:1237–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang CI, Kim SH, Park WB, et al. Bloodstream infections caused by antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacilli: risk factors for mortality and impact of inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy on outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:760–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cain SE, Kohn J, Bookstaver PB, Albrecht H, Al-Hasan MN. Stratification of the impact of inappropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy for Gram-negative bloodstream infections by predicted prognosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:245–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Executive summary: implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:1197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell BG, Schellevis F, Stobberingh E, Goossens H, Pringle M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timbrook TT, Morton JB, McConeghy KW, Caffrey AR, Mylonakis E, LaPlante KL. The effect of molecular rapid diagnostic testing on clinical outcomes in bloodstream infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee R, Teng CB, Cunningham SA, et al. Randomized trial of rapid multiplex polymerase chain reaction-based blood culture identification and susceptibility testing. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1071–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacVane SH, Nolte FS. Benefits of adding a rapid PCR-based blood culture identification panel to an established antimicrobial Stewardship Program. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54:2455–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marschal M, Bachmaier J, Autenrieth I, Oberhettinger P, Willmann M, Peter S. Evaluation of the accelerate pheno system for fast identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing from positive blood cultures in bloodstream infections caused by Gram-negative pathogens. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55:2116–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee R, Komarow L, Virk A, et al. Randomized trial evaluating clinical impact of RAPid identification and susceptibility testing for Gram-negative bacteremia: RAPIDS-GN. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dare RK, Lusardi K, Pearson C, et al. Clinical impact of accelerate pheno rapid blood culture detection system in bacteremic patients. Clin Infect Dis 2020; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehren K, Meißner A, Jazmati N, et al. Clinical impact of rapid species identification from positive blood cultures with same-day phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing on the management and outcome of bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70:1285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pancholi P, Carroll KC, Buchan BW, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the accelerate phenotest BC kit for rapid identification and phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing using morphokinetic cellular analysis. J Clin Microbiol 2018; 56:e01329-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Humphries RM, Abbott AN, Hindler JA. Understanding and addressing CLSI breakpoint revisions: a primer for clinical laboratories. J Clin Microbiol 2019; 57. Available at: https://jcm.asm.org/content/57/6/e00203-19. Accessed 18 January 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Supplement M100. 29th edn. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994; 47:1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Hasan MN, Juhn YJ, Bang DW, Yang HJ, Baddour LM. External validation of bloodstream infection mortality risk score in a population-based cohort. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20:886–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008; 36:309–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Patient Safety Component Manual. Chapter 4: Bloodstream infection event (central line-associated bloodstream infection and non-central line associated bloodstream infection). 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/pcsmanual_current.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHSN antimicrobial use and resistance module protocol.2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/11pscaurcurrent.pdf. Accessed 30 November 2020.

- 22.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2020. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurer FP, Christner M, Hentschke M, Rohde H. Advances in rapid identification and susceptibility testing of bacteria in the clinical microbiology laboratory: implications for patient care and antimicrobial Stewardship Programs. Infect Dis Rep 2017; 9:6839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eby JC, Richey MM, Platts-Mills JA, Mathers AJ, Novicoff WM, Cox HL. A healthcare improvement intervention combining nucleic acid microarray testing with direct physician response for management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Angelis G, Grossi A, Menchinelli G, Boccia S, Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B. Rapid molecular tests for detection of antimicrobial resistance determinants in Gram-negative organisms from positive blood cultures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26:271–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seddon MM, Bookstaver PB, Justo JA, et al. Role of early de-escalation of antimicrobial therapy on risk of Clostridioides difficile infection following enterobacteriaceae bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:414–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webb BJ, Subramanian A, Lopansri B, et al. Antibiotic exposure and risk for hospital-associated Clostridioides difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64:e02169–-19.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CLSI. Verification of commercial microbial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing systems. 1st ed. CLSI Guideline M52. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humphries RM, Ambler J, Mitchell SL, et al. CLSI methods development and standardization working group best practices for evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility tests. J Clin Microbiol 2018; 56. Available at: https://jcm.asm.org/content/56/4/e01934-17. Accessed 28 January 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.