Abstract

Objectives

To develop an understanding of health professionals’ experiences of working at the point of care during the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact on their health and well-being and their support needs.

Design

A qualitative study using semistructured interviews. Data were analysed using framework analysis.

Setting

One large National Health Service integrated care trust.

Participants

A purposive sample of 19 qualified health professionals (doctors, nurses or allied health professionals), working with patients with COVID-19 admitted to the hospitals between March and May 2020 were eligible to take part.

Results

Eight major categories were identified: (1) Working in a ‘war zone’, (2) ‘Going into a war zone without a weapon’, (3) ‘Patients come first’, (4) Impact of COVID-19, (5) Leadership and management, (6) Support systems, (7) Health professionals’ support needs, and (8) Camaraderie and pride. Health professionals reported increased levels of stress, anxiety and a lack of sleep. They prioritised their patients’ needs over their own and felt a professional obligation to be at work. A key finding was the reported camaraderie among the health professionals where they felt that they were ‘fighting this war together’.

Conclusions

This study provides a valuable insight into the experiences of some of the frontline health professionals working in a large London-based hospital trust during the first COVID-19 peak. Findings from this study could be used to inform how managers, leaders and organisations can better support their health professional staff during the current pandemic and beyond.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

At the time when the study was undertaken little was known about UK frontline health professionals’ experiences of working during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A qualitative methodology enabled in-depth data collection about their needs and experiences.

Use of framework analysis enabled data exploration while simultaneously maintaining an effective and transparent audit trail.

Due to the qualitative nature, the study findings may not be representative of the experiences and views of all UK frontline health professionals but nonetheless it provides useful insights into their experiences.

Background

Healthcare professionals have been at the forefront of dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic since March 2020. The virus initially spread rapidly in London compared with the rest of the country and placed an overwhelming demand on the National Health Service (NHS). Doctors, nurses and allied health professionals are at the forefront of the NHS, working under extremely difficult conditions during this pandemic and therefore likely to be at an increased risk of negative impacts to their health and well-being.

A quantitative study from China reported that frontline healthcare providers treating patients with COVID-19 had greater risks of mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, insomnia and stress.1 Currently, there is a longitudinal survey, the impact of COVID-19 on the Nursing and Midwifery workforc (ICON) study, under way in the UK led by the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) Research Society Steering Group, in collaboration with a number of universities.2 This survey is evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on the UK nursing and midwifery workforce at three time points: prior to COVID-19 peak, during the COVID-19 peak and in the recovery period following COVID-19. The first survey of 2600 members of the nursing and midwifery workforce suggested that 74% felt their personal health was at risk, 92% were worried about risks to their family members due to their clinical role and almost 33% reported severe or extremely severe depression.2 The responses from this first survey highlighted the need to provide supportive interventions during and after COVID-19 to support individual’s psychological and physical health needs. According to the project lead Dr Keith Couper, ‘urgent research is needed to develop and evaluate interventions to support individuals’.2

A qualitative study of the experiences of healthcare providers in China suggested that nurses and physicians were challenged by working in a totally new context, and reported exhaustion due to heavy workloads and protective gear, the fear of becoming infected and infecting others, feeling powerless to handle patients’ conditions and difficulty in managing relationships in this stressful situation.3 At the time when this study began there were no other qualitative studies undertaken or published to inform how health professionals would like to be supported to maintain and/or enhance their physical and mental health and well-being. NHS trusts across the country are offering many well-being resources aimed at their staff, but it is not known whether these are adequate to meet the needs of health professionals working during the pandemic. This study was therefore designed to gain a better understanding of frontline health professionals’ experiences and highlight ways in which doctors, nurses and allied health professionals want to be supported during these extraordinary times. The findings from this study can help shape services to provide better support to their health professionals during the coronavirus pandemic and any subsequent waves in the future.

Aims/objectives

The aim of this study was to provide a broader understanding of the experiences and needs of doctors, nurses and allied health professionals during and after the COVID-19 outbreak, and how they could be better supported. There were three main objectives, which were to gain a broader understanding of:

Frontline health professionals’ experiences of working during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The reported impact of this work on frontline health professionals’ physical and mental health.

How doctors, nurses and allied health professionals could be better supported to promote/enhance their physical and mental well-being during and after COVID-19.

Methods

A qualitative approach was used to address the study aims and objectives. Doctors, nurses and allied health professionals were recruited from three hospital sites across a large London-based hospital trust. Data from the Office for National Statistics showed that the borough in which the hospital is situated was the second most affected by the COVID-19 virus in London,4 therefore this trust was considered to be ideal for this study.

Any qualified doctor, nurse or allied health professional working with patients with COVID-19 admitted to the hospitals between March and May 2020 were eligible to take part. Students, managers and those not providing direct patient care were excluded.

Inclusion criteria

Qualified doctor, nurse or allied health professional.

Working during March to May 2020.

Providing direct patient care.

In one of the trust hospital sites.

Exclusion criteria

Student nurses/student doctors/student allied professionals.

Agency staff, not employed by the trust.

· Managers (non clinical, those not working directly with patients)

Those not providing direct patient care.

Those not working during the period between March and May 2020.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient involved in this study.

Three healthcare professionals were involved in guiding the planning and conduct of the study. Nurses contributed to the development of the study protocol. An independent clinical representative was involved in the data analysis process.

Data collection

At the time of the study, both authors worked in the hospital trust where the study was undertaken. The study was advertised using posters at all hospital sites and those interested in taking part contacted the researchers. Participants were given a participation information sheet and written informed consent (online supplemental appendix 1) was obtained prior to participation. One-off in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted as per the study protocol which was developed prior to study commencement. Interviews (including face to face and telephone) were conducted by both authors with a purposive sample of 19 health professionals meeting the inclusion criteria, until no new information was forthcoming and data saturation was reached. All interviews took place between July and October 2020. Both interviewers had prior experience of conducting qualitative interviews and a topic guide was developed to provide structure and focus (online supplemental appendix 2), which was piloted during the first two interviews conducted by each author. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed using an approved transcription service. All interviews took place ensuring privacy, with no one else present apart from the participant and interviewer. Participants were offered an opportunity to check their interview transcript for accuracy and provide feedback prior to analysis. The duration of the interviews varied between 15 and 60 min, with the average being 33 min. Fieldnotes were written after each interview to record aspects of the interview that may not be captured on the recording such as environment, context, general observations and thoughts.

bmjopen-2021-054377supp001.pdf (23.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-054377supp002.pdf (49KB, pdf)

Data analysis

The research team consisted of the first author (SB), who undertook all aspects of this study, with support from the second author (JG) who was involved in developing the study protocol, study design, data collection and data analysis. None of the study participants worked in the authors’ own teams. An independent clinical representative (who was not involved in the data collection process) was involved in the data analysis process for quality assurance and to reduce any risk of bias. Data were analysed using thematic analysis informed by framework analysis and the five steps of data management: familiarisation; constructing an initial thematic framework; indexing and sorting; reviewing data extracts; and data summary and display, followed by a process of abstraction and interpretation.5 6 This method was chosen as it would enable the identifying, analysing and interpreting of patterns and meaning within qualitative data. Furthermore, this method is not tied to a particular epistemological or theoretical perspective, making it very flexible and appropriate for this study.7 The computer software package NVivo (V.11) was used to facilitate this process.

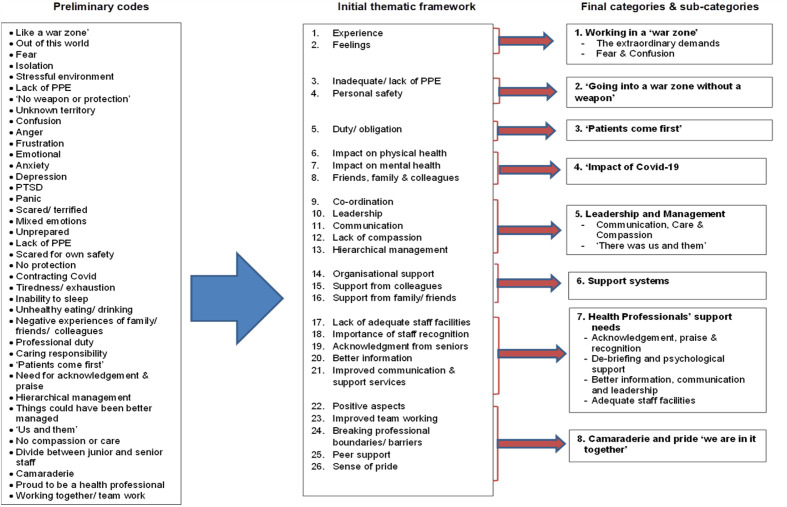

During the familiarisation stage the interviews were listened to independently by both interviewers and the transcripts were read several times before initial themes were identified. These themes were discussed and checked against the interview topic guide and study objectives, resulting in the development of a set of preliminary codes (figure 1). These initial codes were used to construct an initial thematic framework by grouping themes that linked particular items and sorting them accordingly to different levels of generality.6 Through indexing and sorting, data were sorted into thematic sets, reviewed and organised by theme and by participant, into matrices before the data were reviewed and analysed to create the final categories and subcategories (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preliminary codes, initial thematic framework and final categories and subcategories. PPE, personal protective equipment; PTSD, post traumatic stress disorder.

Study rigour

‘Trustworthiness’ is central to ensuring quality of the study, which involves establishing credibility, dependability, transferability and confirmability.8 These aspects were systematically considered during the study. To enhance the credibility of the data, following interviews, participants were provided an opportunity to check their transcripts, data analytics categories, interpretations and conclusions. Feedback was obtained from participants to ensure that their views and experiences were accurately interpreted and represented, rather than being influenced by the researcher’s own views and beliefs. The use of framework analysis enabled a step-by-step process for data management, which is transparent and replicable, thus providing a clear audit trail and enhancing the dependability of the study findings. The methods for this study have been described in detail to allow readers to make informed decisions about whether the findings can be transferred to another setting or context. Confirmability refers to the extent to which the findings of a study are shaped by the respondents and not researcher bias, motivation or interest and is established when credibility, transferability and dependability are all achieved.8 Reflexive journals were kept throughout to document the researchers’ personal reflections of their values, interests and insights. This was important in enabling the researchers to acknowledge any potential risk of personal bias.

Ethical consideration

The study was conducted in compliance with the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care and Good Clinical Practice. All interviews were carried out on a voluntary basis and participants could withdraw from the study at any stage, although none chose to do so. The interviews were transcribed with the principle of anonymity in mind and a confidentiality agreement was in place for the approved transcribing service used. Professional backgrounds of participants or the specific site that they worked at have not been presented in the ‘Participant Characteristics’ table to minimise the risk of individuals being identified due to the small sample size.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 19 participants, 6 were doctors, 8 were nurses and 5 were allied health professionals (to include physiotherapists, speech and language therapists). There was representation from junior (clinicians with minimal management responsibilities) and senior members (clinical managers and leaders) of staff from each of these professional groups. Participants’ ages ranged from 29 to 59 years, and over two-thirds of the participants were female (n=13), with six being male. Nine described their ethnic background as White (English=8, Irish=1); seven as Asian (Indian=5, Pakistani=1, Mauritian=1); and three as Black (British=1, Caribbean=1, Other=1). All three hospital sites were represented in the sample. See table 1 for full participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| No | Sex | Age | Ethnicity |

| P1 | F | 45–49 | White/English |

| P2 | F | 25–29 | White/English |

| P3 | F | 30–34 | Asian/Indian |

| P4 | M | 30–34 | Asian/Indian |

| P5 | F | 40–44 | White/English |

| P6 | F | 55–59 | White/English |

| P7 | M | 25–29 | Asian/Indian |

| P8 | F | 30–34 | White/English |

| P9 | M | 30–34 | Asian/Indian |

| P10 | M | 30–34 | White/English |

| P11 | F | 40–44 | Black/Caribbean |

| P12 | M | 30–34 | Asian/Mauritian |

| P13 | F | 45–49 | White/English |

| P14 | F | 25–29 | Asian/Indian |

| P15 | F | 30–34 | White/Irish |

| P16 | M | 25–29 | Asian/Pakistani |

| P17 | F | 35–39 | White/English |

| P18 | F | 35–39 | Black British |

| P19 | F | 45–49 | Black Other |

Eight major categories (and subcategories) pertaining to frontline health professionals’ experiences, impact and needs were identified from the data:

Working in a ‘war zone’.

‘Going into a war zone without a weapon’.

‘Patients come first’.

Impact of COVID-19.

-

Leadership and management.

Communication, care and compassion.

‘There was them and us’.

Support systems.

-

Health professionals’ support needs.

Acknowledgement, praise and recognition.

Debriefing and psychological support.

Better information, communication and leadership.

Adequate staff facilities.

Camaraderie and pride: ‘we are in it together’.

Working in a ‘war zone’

Health professionals described their experience as working in a ‘war zone’. They talked about the enormity of it as:

It was like that scene on ET, all that plastic.… So, there’s all this plastic and, I get it, but just walking into this other world, there was just mayhem, pandemonium. People running around, alarms going off.… it was like a war zone. That’s how everyone equated it to, that the rules had completely changed, absolutely changed. (P1)

It was something that they had never experienced before or even anticipated and described it as an ‘out of world’ experience which they were not prepared for:

…you are like an astronaut going to some special mission, like you are going inside a special room, something like that. And it was really tough, in fact, there were like so many sick patients, so many young sick patients coming, plus the older sick patients. (P4)

Health professionals talked about the fear they felt coming into work, they described it as being ‘absolutely terrifying’, ‘pure fear, pure anxiety, of death’ (P1), and that ‘the mental fear was something awful’ (P3).

I remember walking into the ward and just this feeling of dread of like, ‘OK. I don’t really want to be here, but I know that I’ve just got to get on and do it.’ (P13)

Some also described feeling confused, angry and frustrated with the speed in which everything progressed, resulting in additional demands placed on staff.

‘Going into a war zone without a weapon’

Personal safety and the lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) featured strongly in the interviews, leaving health professionals feeling disappointed, frustrated and angry about not being adequately protected. Many compared it to being in a war zone without a weapon.

It’s like a basic right to be protected. Like, this is a war. You wouldn’t send soldiers out without any…. weapons… equipment and armour and guns, that kind of stuff. Like, you have to be protected. (P2)

…police officers don’t go out without a stab vest, firemen don’t go out without wearing the full protective gear … why are healthcare staff any different? Why are we not provided with the appropriate [PPE]. (P12)

It was like I’m going to the war zone and I’ve got no weapon. Where is my weapon? (P11)

The shortage of PPE meant that health professionals avoided discarding their masks or taking adequate breaks due to the fear of their PPE not being replaced:

‘Well, I need to go out to the loo, and I better not because there might not be PPE to be able to get back in. So, I better hang on, or do I really need my break. Maybe I won’t have my break.’ So, that was difficult. (P6)

Health professionals recognised the national PPE guidance was constantly changing, and although this was frustrating they wanted:

… more support from the trust, needed to be updated, needed, and I think more help and guidance on like the PPE I think was a big issue. Because one week you had to wear full gown, full apron, the whole shebang, and then the next week no you didn’t…. There were all these changes which was affecting all of us. (P8)

‘Patients come first’

There was a strong sense of professional duty among the health professionals, where they prioritised their patients’ needs before their own. This was common among all three professional groups.

I felt that, as a nurse, it’s my duty and it’s my responsibility to be for the patient any time, no matter what comes. (P4)

I think as health professionals I think it’s something we’re good at. People have a sense of duty; they want to help. That’s why they’re there. (P10)

I think as a medical professional it is always very much you look after everybody else and your attitude is always, ‘Yes, I’m fine. Yes, I’m fine. Yes, I’m fine. Yes, I’m fine.’ Even if you’re not fine… (P13)

Nurses described as being adaptable and having to take on multiple roles for their patients, ‘to be a carer, they had to be a comforter; they had to be an advisor, a counsellor to the families. At the same time, to be a nurse’ (P4).

Some talked about the change in public perception of healthcare professional during the pandemic and found being called ‘Heroes’ and being clapped for an uncomfortable experience, when they were simply fulfilling their duties:

…with the whole clapping and just how the government sort of dealt with things. I just felt it was really embarrassing. (P9)

I think as a doctor you—or as a nurse, or actually anybody in health, it’s, ‘Oh, you work for the NHS,’ and it’s so taken for granted, and just that change of feeling of the country of, ‘The NHS has to save us,’ and suddenly you’re sort of put up as these amazing people that do all of these incredible things, and you think, ‘Well, I’m just doing what I always do.’ (P13)

Impact of COVID-19

Working during the pandemic had a negative impact on most participants. Some talked about contracting COVID-19 and the symptoms associated with the infection, while many talked about the exhaustion and tiredness of working during this demanding period and the impact on their mental health:

I actually don’t think I’ve really experienced anxiety to this level that I had at the beginning of this pandemic. (P9)

I remember one day I finished my shift, outside, my car, and I cried in the car park. (P18)

Participants talked not being able to sleep due to the increased levels of anxiety at work and how that impacted on their physical and mental health:

So there was a lot of unhealthy eating and kind of not sleeping at the same time, stress levels were quite high, anxiety was quite high. So that did have an impact, and I’m sure this had impacted on my blood pressure, worsened my cardiovascular risk … but I’ve not formally measured it. (P12)

…from the beginning of it, I wasn’t sleeping. I’d done three weeks of long days, and I wasn’t sleeping. And it was really affecting me. Everything was affecting me. And I ended up having PTSD, it was diagnosed as. So, I ended up being really anxious. (P1)

Having to come into work also had a negative impact on participants’ family members which often added to their existing anxieties. They talked about family members being distressed and worried about their safety.

Leadership and management

Communication, care and compassion

Health professionals described varying experiences relating to leadership and management. In areas where there was good communication and support, it resulted in positive experiences, as reflected below:

…my manager always used to come around and have a look around us, make sure that those who are on work were well taken care of. Come and chat with us, ask us how is everything, is everything OK, and then to support in that time, like we had. (P4)

We had quite clear leadership and … although information was changing, we were told why it was changing, what was going on, we understood the changes to the department physically, we understood as we became more aware of what the patients were presenting like, a better idea of what to do next with them. (P17)

Many, however, felt that they were not treated with care or compassion by their senior managers, as a redeployed nurse, speaking about the nurse in charge stated:

Not a word of appreciation, not a word of thank you, and she didn’t just ask me, ‘Are you OK? Can you go home? Are you OK to handover?’ Nothing. She just stood at the door and she waved her hand [good-bye]. (P3)

Similar feelings were expressed by medical staff where one felt ‘…doctors were being treated as numbers once again, and healthcare staff just being treated like numbers’ (P9). This health professional went on to say:

I generally don’t think the working environment for NHS is that well supported, just generally, despite COVID. That’s just personally how I feel. I feel like medicine as an institution there still exists a lot of bullying, there still exists a lot of competitive natures, like cutthroat, which is part of the process. (P9)

Some felt that they were not being listened to and compassion was lacking from their managers:

…I felt like I was being patronised….I thought it was forced, but I felt our voice as staff was not heard….our needs was not met…. Compassion was not shown…. Caring was not shown, and that did not sit well with me because we are a nursing profession and our role is to show compassion and caring. (P11)

‘There was them and us’

There was a general feeling among most junior health professionals that there was a hierarchical management system where the senior manager/leaders were less visible at the frontline during the pandemic:

You didn’t really see much of a physical presence of anyone from the higher management that were on the shop floor telling you, ‘Well done’, or ‘Thank you for what you’re doing.’ So that I didn’t feel that we were supported from the kind of higher-up management. (P12)

I have never seen any of the management people in the PPE to come in and to see what happens. (P3)

The lack of communication between senior and junior staff seems to play a big part in staff feeling this divide:

The Band 8s [managerial/leadership role] have been involved in various meetings, and they’ve been involved with things or making decisions that we’ve felt that they could have, ‘Can we just share your experience?’ they’ve not really shared our experience and they sometimes make some sweeping statements of what we’re going to do and how we’re going to change. It would have been nice if they could have talked to us. (P6)

Decisions were made where I was working, and it can be a bit hierarchical at times. I think communication around the decisions was often a bit convoluted…. (P10)

Support systems

Most health professionals were aware of a range of support services provided by the organisation. They particularly valued the regular ‘Communication’ emails and the information available on the trust intranet. Most also mention the support on offer from the psychology team and some had accessed this service. Some, however, talked about the difficulties associated with being able to access the services on offer:

I know there is some, but if I’m honest I’m not exactly sure how I would go about going into it. I know during the pandemic they were putting on some things, but unfortunately they were often like at times when I was in working or on shift or something. So, I wasn’t able to get along. (P10)

Most staff, however, accessed support from their team members and work colleagues, and found this to be beneficial:

…work colleagues would try and support each other. There was a bit of a more team ethos. So that helped with coping with the stress, and just … bounce some of the issues that we had with each other. (P12)

Support from friends and family also played an important role in helping health professionals deal with their stress and anxieties.

Health professionals’ support needs

Acknowledgement, praise and recognition

Participants wanted to feel valued by being acknowledged, recognised and praised by senior leaders and managers for the work that they were doing during this difficult time. They wanted this to be a personalised approach rather than a generic one:

I think recognition of the team’s effort by the trust, not a generic e-mail or a thank-you that gets sent, but … somebody from senior management actually coming down and saying to people on the shop floor, ‘Well done for what you’ve done, and thank you for what you’ve done.’ I know it’s part of our job, but sometimes you do feel undervalued…. by the trust in terms of how things are. (P12)

Debriefing and psychological support

Health professionals wanted opportunities to debrief and to have access to psychological support. Having this support available locally in their own work settings/departments was thought to be more appropriate in encouraging staff to access it more readily:

…if there was someone like to come to us when we are in the clinical setup, if there is someone to come to us and to speak to us, like during our breaks. (P3)

Whereas I do think sometimes if there’s a person or a presence of someone to come, and you can kind of put a face to it, that, for me personally, makes it more relatable and perhaps less intimidating to go and have these conversations or join these classes and things that you want to do. (P10)

Some suggested having protected time would enable staff to collectively reflect on their experiences, debrief and share learning while also focusing on the positive outcomes:

…also focussing on the positives. Like, the positive case studies. So, somebody that came in and they’re treatment from beginning to end. (P2)

I think it would be really nice to get together and have a sort of, like, you know, be reflective, talk about what we didn’t enjoy, well what went wrong, how we can improve. Because if there was to be a second wave again, then we can learn from it and put those ideas forward. (P8)

Better information, communication and leadership

Health professionals wanted improved communication from managers and leaders and this to be provided locally, face to face, rather than through emails:

I just think we just need more support and just to be updated, to be told what’s happening. I know we’re getting the regular emails, but specifically to our ward, what’s happening [ward], and having like maybe a weekly meeting or something too. (P8)

…perhaps having someone come to where you work to explain exactly what’s available. (P10)

Junior health professionals wanted to be informed and involved in the decision-making process around issues that affected them, one person stated:

The only thing I would love to happen is most probably, is for the Trust to support probably—to incorporate the lower grade staff in their decision making. (P11)

The need for improved leadership through having a senior health professional oversee the team or department was seen as being important. A nurse who was redeployed to another area of work stated:

I should say there should be someone to overlook, like it will be great, if we are deployed, if we get a person, like a specific person ‘this many group of people can speak to this person specially and that person is available at the clinical centre’…. If there is a specific person like that, like we can share our concerns and issues. (P3)

The overall feeling was that:

There could have been more leadership from the seniors to create an environment that was like, you know, ‘If you don’t feel like you should be working, please come and see us, or please to go occupational health,’ or maybe there should have been more emails given by occupational health to see if we were suitable to work. (P9)

More involvement from managers and working together with health professionals at the frontline was viewed as being necessary to being an effective leader:

I would suggest is, managers take front line if it happens again, because that in itself will prevent your staff from calling sick. That in itself will motivate your staff from getting up in the morning, from coming to work. I know we have managers things to do, but just for two days, you can do it for days. (P11)

Adequate staff facilities

As health professionals working on the frontline, participants wanted their basic needs to be met. They wanted to have access to adequate clothing (scrubs), PPE and facilities for changing, showering and resting, as reflected below:

I would like a simple thing, like we have a space to just relax or like we have some time off…So I just feel like if we have some kind of a small, like an entertainment or a relaxing zone anywhere in our hospitals where staff can sit down and relax…Like it could be anything, like we have a refreshing zone or like we have a small gaming zone or like we have a small sofa, a two-seater relaxing sofa. Or we have some Internet facility or like we have books to read or anything of that kind of a zone. (P4)

More importantly, an area where I could leave my clothes and my shoes, change into scrubs and shoes and then, at the end of my shift, have an area again where I can take away my dirty clothes, maybe have a shower, clean myself, sanitise myself, put on my clean clothes and go back out. (P12)

Overall, health professionals felt it was ‘important to make sure everything is put in place, all the PPEs, all the right gears are put in place’ (P19).

Camaraderie and pride: ‘we are in it together’

Working during the pandemic brought about a sense of camaraderie among the health professionals, which was seen as a positive aspect.

Participants’ comments included:

We’ve got closer. There’s just a camaraderie.… it’s that kind of thing, like we’ve all been through it, and … no, not with my colleagues. If anything, it’s affected it for the better. (P1)

I feel like there’s a community within nursing, and then there was a community within caring for people with COVID, because it was such a like exceptional circumstance and then everyone was in it together, and it was so horrible that I feel like we had a—I almost feel like we had a mutual understanding of each other and a mutual respect. (P2)

They were all together working as nurses for a single goal—treat COVID-19 patients. (P4)

This camaraderie was felt among all three professional groups, and health professionals reported working together across professional boundaries, breaking some of the traditional practices, as demonstrated in the following statements:

I think it was one of the positives from the whole thing was the camaraderie I felt with other people on the unit where I work. ….so, where we were, we weren’t able to do certain things as therapists, so we were doing a lot of nursing shifts instead, and it was sort of a real roll your sleeve up and muck in. (P10)

…on the shop floor we supported one another. That was very… there was that team ethos, …. if I had gone into the bay, and a patient had requested to use a commode, for example, instead of me calling for a nurse or for a HCA to give the commode, because I’m already there in the bay, I would take the commode and tend to the patient… (P12)

… there was a lot more camaraderie…. we got to know colleagues from around the rest of the hospital, and we were suddenly just all pulling together, whereas before, there would be the usual tensions…. All that had gone, really, we were all trying to work together. (P17)

In addition, health professionals felt a sense of pride in being able to contribute to this crisis and as a result better prepared to take on such challenges in the future. One clinician stated: ‘I think what we had was the worst and still we managed it, so we have that experience in our hand, that will help us’ (P7).

Another said:

I think it’s made us stronger really, because we worked well as a team. So, we’ve overcome like many challenges, and we have, you know, to say that I was a nurse on the front line is, not to say it’s an accomplishment, but you’re never going to forget that. (P8)

Seeing the speed in which changes were made within the healthcare setting was another positive aspect, as reflected below:

I think it was interesting seeing, actually, when there was a massive crisis like this how within health how actually things could change so quickly. So, there’s often so much inertia, months and months go by, decisions aren’t made, ‘You can’t do this. No we can’t do that. No we’ve never done it like this, so we can’t do that,’ and actually it was quite enlightening to see that actually when things need to change and they need to change quickly, they did. And there were huge changes within the Trust, moving wards, increasing intensive care beds, mobilisation of staff, everybody doing different roles, and that for me was brilliant to see, that actually it can happen. (P13)

Discussion

Frontline health professionals in this study compared their experience of working during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic to working in a war zone. The analogy used could be explained by the unprecedented situation they found themselves in, having to balance the needs of their own families against the demand of their jobs. Most were fearful of coming to work after witnessing high volumes of deaths caused by the virus. The situation was made worse by the lack of adequate PPE available to them, resulting in health professionals feeling disappointed, frustrated and angry. Again, health professionals compared the situation to being in a war zone without a weapon. At the time, a similar picture was seen across the UK with reports of inadequate provisions of PPE,2 9 as well as inadequate COVID-19 testing for healthcare staff10 and unclear infection control policies in some healthcare settings.11 Maben and Bridges posit that the failure to protect nursing staff adequately could result in anger and frustration, leading to many leaving the profession.12 This could also apply to doctors and allied health professionals working in such conditions.

Most health professionals in the current study reported increased levels of stress, anxiety and a lack of sleep. This is hardly surprising as evidence from studies on previous outbreaks of emerging viruses (including SARS, COVID-19, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Ebola and influenza) suggests that up to a third of staff will experience high levels of distress.13 Healthcare workers in countries that experienced the peak of COVID-19 infection earlier than the UK were more likely to experience symptoms of anxiety and depression than before the pandemic.14 Reports of stress, anxiety, depression and insomnia in health professionals working on the frontline during COVID-19 have also been reported in other studies carried out in the UK5 and internationally.15–19 In a survey of 996 health and social care staff (75% of whom were employed by the NHS) by the Institute for Public Policy Research, 50% reported that their mental health had declined during the first 2 months of the pandemic.20 In another survey of 921 allied health professionals, 86% reported feeling stressed with regard to changes in their work environment and transmission of the virus.21 Interestingly, in this study, levels of stress were dependent on access to PPE and mental health resources.21 Similarly, in other surveys, 45% of doctors reported experiencing depression, anxiety, stress, burn-out or other mental health conditions related to the outbreak (undertaken in May 2020),9 and 33% of nurses and midwives reported severe or extremely severe depression, anxiety or stress (undertaken in April 2020).2 Additionally 6 months into the pandemic, 76% of almost 42 000 nurses surveyed by the RCN reported an increase in their stress levels since the advent of the pandemic, with 52% concerned about their mental health.10

Frontline health professionals’ mental health needs to be adequately supported especially as this is a workforce that was already experiencing high levels of stress prior to the pandemic. In the decade preceding the onset of the pandemic, symptoms of anxiety and depression were reported in between 17% and 52% of doctors,22 with potentially higher levels among nurses.23 There is a well-evidenced link between staff well-being and quality of care delivery. The WHO has recently highlighted that ‘keeping all staff protected from chronic stress and poor mental health during this response means that they will have a better capacity to fulfil their roles’.24 Conversely, without good mental health or psychosocial support for health professionals there is a risk to the quality of care delivered to their patients.25 Focusing on the health and well-being of nursing staff is essential to the quality of care provided as it affects an individual’s level of compassion, professionalism and effectiveness.26

Healthcare professionals are often reported to be good at coping and have a strong belief that they should be able to deal with anything that comes along in their personal or professional domain.27 This was evident among the health professionals in this study where they prioritised the needs of their patients over their own and felt a professional obligation to be at work. This can often generate a superhuman philosophy that makes it difficult for healthcare professionals to admit that they are experiencing stress,27 a trait that was also seen among the participants in this study. This may have implications for how these health professionals are supported during such difficult times.

In this study, most health professionals were aware of the services available to them through their organisation, including support from psychological services. However, they wanted a more personalised approach to dissemination of information through face-to-face contacts and debriefs. Health professionals reported good levels of support from their work colleagues and family members, but a ‘disconnect’ between junior and senior staff. Interestingly, Maben and Bridges reported findings from studies of members of the armed forces where team cohesion was noted horizontally (between colleagues) and vertically (between leaders and their teams).12 This was also highly correlated with mental health, with a reported 10-fold difference in trauma-related mental health status between troops who perceived themselves as having a good or bad leader.28 In the current study, where there was good communication and staff felt supported, they reported good leadership. A lack of communication, care and compassion was associated with a divide between managers and junior health professionals. Therefore, there are a number of things that managers and leaders could do to improve staff well-being. This includes being visible and approachable and inviting feedback from team members; communicating regularly in an honest and open manner, acknowledging team members’ contributions and providing praise; and prioritising well-being, mandating breaks and creating opportunities for teams to meet together.12 29–31 There may have been legitimate reasons for senior managers and leaders not being visible during this study as they were also faced with this unprecedented situation, having to make changes based on the rapidly changing national guidance; however, if this was communicated to the frontline staff then that may have reduced the ‘divide’ felt by participants between junior and senior staff. It is also important that senior health professionals seek support for themselves, so that they have the capacity to support others and are able to role model good self-care.12 Health professionals in this study highlighted a need for access to psychological therapies and opportunities for reflective space to enable them to think about their experiences and process their emotions.

Another important need identified by the health professionals was the lack of adequate facilities within their workplace for breaks, rest, showering, dressing or storing personal belongings. Referring to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, physiological and safety needs are the first two levels which must be met before individuals can be motivated and turn their attention towards others.32 Therefore, it is fundamental that health professionals’ basic needs are prioritised by ensuring the availability of adequate facilities to meet their physiological needs, as well as access to adequate protective equipment to meet their safety needs, as discussed previously. This has also been highlighted by other researchers.33 34

A positive aspect of this study was the camaraderie seen across the frontline health professionals. The pandemic has created a special professional bond among the staff where they felt that they were fighting this war together. In the military, bonds between team members have been reported to build resilience among troops,35 which echoes the messages from the participants in this study. Health professionals working together across professional boundaries is a welcomed move which will hopefully continue beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in more collaborative working among nurses, doctors and allied health professionals.

It is acknowledged that due to the qualitative nature of this study and the small sample size, the study findings may not be representative of the experiences and views of all frontline health professionals within the organisation. Study limitations also included that only volunteer frontline health professionals participated, which may have resulted in recruiting those who were specifically interested in the topic area. Also only nurses, doctors and allied health professionals working within the acute setting were included. It is recognised that health professionals from other groups (such as midwives, healthcare assistants, students, etc) and settings (community, clinics, primary care, etc) may have similar experiences, which were not captured in this study and would benefit from being included in future studies. This study, however, provides a valuable insight into the experiences of some of the frontline health professionals working in a large London-based hospital trust during the first COVID-19 peak. Findings from this study could be used to inform how managers, leaders and organisations can better support their clinical staff during the current pandemic and beyond. Health professionals who are better supported in practice give better care to patients, increasing staff engagement and improving retention rates.36 Being able to better support the needs of the clinical workforce could therefore also contribute to better patient care and improved retention of clinical staff during and after this pandemic.

Implications for practice

There are a number of recommendations for individuals, managers/leaders and organisations to improve the health and well-being of frontline health professionals.

Individuals

Health professionals need to look after themselves by taking regular breaks, keeping hydrated and eating well. It is important to be aware of the support services available and use them when necessary. Asking for help when not coping should not be seen as a weakness. It is also important to feel proud of individual achievements and celebrate them. Individuals can also look out for their colleagues and offer them support if they need it (including talking, signposting them to supportive resources, promoting their well-being).

Managers/leaders

Managers and leaders need to look after themselves too, so that they have the capacity to support others and role model good self-care. Being visible, approachable and available during a crisis can convey care and compassion to junior staff and other team members. It is important to maintain regular, honest and open communication with team members, creating opportunities for debriefing and inviting feedback. Involving team members in decision-making processes, acknowledging their contributions and providing regular praise can help staff feel more supported. Prioritising staff well-being, mandating breaks and creating access to adequate facilities (such as rest areas, showering and changing facilities, etc) are essential to ensuring staff well-being. It is crucial that those in managerial and leadership roles are aware of all available support services so that they can use them and signpost others to as necessary.

Organisations

Providing adequate food, drink, rest facilities; staff safety; and ensuring that staff do not exceed safe working hours should be a priority for all healthcare organisations. Organisations should proactively address resource inequities and provide regular situational updates for all staff, including realistic and frank information about risk and adverse events. It is important to provide regular praise and acknowledgement to increase staff morale. Organisations should support all managers and leaders to develop their skills to support their teams, such as debriefing practices, identifying psychological distress and the promotion of mental health and well-being. Access to adequate psychological support should be offered. Good communication at all levels is essential so that junior staff are given opportunities to voice their concerns and be heard. Where possible, information should be disseminated using personalised approaches, through forums, meetings and regular briefings as well as other formal methods (emails, newsletters, etc).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the health professionals who took part in this study, for sharing their views and personal experiences during these difficult times, without which this study would not have been possible. We would also like to thank the NHS trust for funding and supporting this study to be undertaken. This study was carried out during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic when everyone throughout the NHS was faced with this unprecedented situation. Since then a Health & Wellbeing strategy has been developed and many wellbeing initiatives have been implemented in the trust where the study was undertaken.

Footnotes

Contributors: SB and JG developed and designed the research proposal, negotiated access to the study site, obtained the required approvals, recruited participants, conducted the interviews and undertook the data analysis. SB wrote the first draft of this paper. JG commented on the draft manuscripts and contributed to the final version of the paper.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Selected anonymised qualitative data from the interviews could be made available on request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Health Research Authority and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) approval was received for this study on 29 June 2020 (IRAS: 286213/REC reference: 20/HRA/3206).

References

- 1.Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e790–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30204-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.University of Warwick . Survey of UK nurses and midwives’ highlights their concerns about health, training and workload during COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://warwick.ac.uk/newsandevents/pressreleases/survey_of_uk [Accessed 21 May 2020].

- 3.Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:e17–18. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ONS . Deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation: deaths occurring between 1 March and 17 April 2020, 2020. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsinvolvingcovid19bylocalareasanddeprivation/deathsoccurringbetween1marchand17april [Accessed 12 May 2020].

- 5.Spencer L, Ritchie J, Ormston R. Analysis: principles and processes. In: Ritchie J, ed. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. 2nd edn. London: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer L, Ritchie J, O’Connor W. Analysis in practice. In: Ritchie J, ed. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. 2nd edn. London: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin S, Bick D. Using framework analysis in health visiting research: exploring first-time fathers’ mental health and wellbeing. JHV 2021;9:206–13. 10.12968/johv.2021.9.5.206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lincoln YS, Guba EG, Pilotta JJ. Naturalistic inquiry. 9. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1985: 438–9. 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.British Medical Association . BMA COVID-19 survey, 2020. Available: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/covid-19/what-the-bma-is-doing/covid-19-bma-actions-and-policy/covid-19-analysing-the-impact-of-coronavirus-on-doctors

- 10.Royal College of Nursing . Researching the impact of COVID-19: icon study, 2020. Available: https://www.rcn.org.uk/magazines/bulletin/2020/june/icon-research-nursing-study-professor-kelly-covid-19

- 11.Williamson V, Murphy D, Greenberg N. COVID-19 and experiences of moral injury in front-line key workers. Occup Med 2020;70:317–9. 10.1093/occmed/kqaa052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maben J, Bridges J. Covid-19: supporting nurses' psychological and mental health. J Clin Nurs 2020;29:2742–50. 10.1111/jocn.15307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloomfield M, Greene T, Billings J. Covid trauma response working group rapid opinion: the case for a trauma-informed response to COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://www.traumagroup.org/

- 14.Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:813–24. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai H, Tu B, Ma J. Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID–19) in Hubei, China. Med Sci Monit 2020;26:e924171:1–16. 10.12659/msm.924171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaukat N, Ali DM, Razzak J. Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a scoping review. Int J Emerg Med 2020;13:40. 10.1186/s12245-020-00299-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simione L, Gnagnarella C. Differences between health workers and general population in risk perception, behaviors, and psychological distress related to COVID-19 spread in Italy, 2020. Available: https://psyarxiv.com/84d2c/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Shreffler J, Petrey J, Huecker M. The impact of COVID-19 on healthcare worker wellness: a scoping review. West J Emerg Med 2020;21:1059–66. 10.5811/westjem.2020.7.48684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, et al. A comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:e60–5. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas C, Quilter-Pinner H. Care fit for carers: ensuring the safety and welfare of NHS and social care workers during and after Covid-19. IPPR, the Institute for public policy research, 2020. Available: https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/care-fit-for-carers

- 21.Coto J, Restrepo A, Cejas I, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on allied health professions. PLoS One 2020;15:e0241328. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imo UO. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among doctors in the UK: a systematic literature review of prevalence and associated factors. British Psychiatric Bulletin 2018;41:197–204. doi:10.1192%2Fpb.bp.116.054247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 2019;10:284. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak, 2020. Available: www.who.int/docs/defaultsource/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf

- 25.Baldwin S, Stephen R, Bishop P. Development of the emotional wellbeing at work virtual programme to support UK health visiting teams. JHV 2020;8:516–22. 10.12968/johv.2020.8.12.516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West M, Bailey S, Williams E. The courage of compassion: supporting nurses and midwives to deliver high-quality care, 2020. Available: www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/courage-compassion-supporting-nurses-

- 27.Royal College of Nursing . Stress and you: a short guide to coping with pressure and stress. healthy workplace, healthy you. London: RCN, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones N, Seddon R, Fear NT, et al. Leadership, cohesion, morale, and the mental health of UK armed forces in Afghanistan. Psychiatry 2012;75:49–59. 10.1521/psyc.2012.75.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA 2020;323:1439. 10.1001/jama.2020.3972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billings J, Kember T, Greene T. Guidance for planners of the psychological response to stress experienced by hospital staff associated with COVID: early interventions. COVID trauma response working group rapid guidance, 2020. Available: https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Guidance-for-planners-of-the-psychological-response-to-stress-experienced-by-HCWs-COVID-trauma-response-working-group.pdf

- 31.Chen S-C, Lai Y-H, Tsay S-L. Nursing perspectives on the impacts of COVID-19. J Nurs Res 2020;28:e85. 10.1097/NRJ.0000000000000389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 1943;50:370–96. 10.1037/h0054346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dewey C, Hingle S, Goelz E, et al. Supporting clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med 2020;172:752–3. 2. 10.7326/M20-1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giannis D, Geropoulos G, Matenoglou E, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on healthcare workers: beyond the risk of exposure. Postgrad Med J 2021;97:326–8. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenberg N, Wessely S, Wykes T. Potential mental health consequences for workers in the ebola regions of West Africa--a lesson for all challenging environments. J Ment Health 2015;24:1–3. 10.3109/09638237.2014.1000676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Employers NHS. Stress and its impact on the workplace, 2019. Available: https://www.nhsemployers.org/retention-and-staff-experience/health-and-wellbeing/taking-a-targeted-approach/taking-a-targeted-approach/stress-and-its-impact-on-the-workplace

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-054377supp001.pdf (23.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-054377supp002.pdf (49KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Selected anonymised qualitative data from the interviews could be made available on request.