Abstract

Objective

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a common complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Several diagnostic prediction rules based on pretest probability and D-dimer have been validated in non-COVID patients, but it remains unclear if they can be safely applied in COVID-19 patients. We aimed to compare the diagnostic accuracy of the standard approach based on Wells and Geneva scores combined with a standard D-dimer cut-off of 500 ng/mL with three alternative strategies (age-adjusted, YEARS and PEGeD algorithms) in COVID-19 patients.

Methods

This retrospective study included all COVID-19 patients admitted to the Emergency Department (ED) who underwent computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) due to PE suspicion. The diagnostic prediction rules for PE were compared between patients with and without PE.

Results

We included 300 patients and PE was confirmed in 15%. No differences were found regarding comorbidities, traditional risk factors for PE and signs and symptoms between patients with and without PE. Wells and Geneva scores showed no predictive value for PE occurrence, whether a standard or an age-adjusted cut-off was considered. YEARS and PEGeD algorithms were associated with increased specificity (19% CTPA reduction) but raising non-diagnosed PE. Despite elevated in all patients, those with PE had higher D-dimer levels. However, incrementing thresholds to select patients for CTPA was also associated with a substantial decrease in sensitivity.

Conclusion

None of the diagnostic prediction rules are reliable predictors of PE in COVID-19. Our data favour the use of a D-dimer threshold of 500 ng/mL, considering that higher thresholds increase specificity but limits this strategy as a screening test.

Keywords: Pulmonary embolism, D-dimer, Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 infection, Computed tomography pulmonary angiography

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged at the end of 2019 and spread rapidly, becoming a major public health problem worldwide [1].

SARS-CoV-2 infection has been recognized as a hyperinflammatory and prothrombotic state, with pulmonary embolism (PE) being one of the most common complications of COVID-19 [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6]].

The diagnostic strategy for PE in the emergency department (ED) is well established, and several clinical prediction rules based on pretest clinical probability and D-dimer measurements have been validated. Although Wells and Geneva scores combined with D-dimer measurement are the most widely used diagnostic criteria for ruling out PE, an age-adjusted approach as well as new algorithms, such as YEARS and PEGeD, have been proposed to safely limit the use of computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) [[7], [8], [9]]. However, all these prediction rules were validated in non-COVID patients, and it remains unclear if they can be safely applied in COVID-19 patients. The diagnostic accuracy of these diagnostic strategies may be impaired on the latter population due to the higher prevalence of PE, increased baseline D-dimers levels and signs and symptoms overlap between both conditions.

This study aimed to compare the diagnostic accuracy of the above-mentioned diagnostic prediction rules for PE in COVID-19 patients admitted to the ED. The primary outcome was to compare the diagnostic accuracy of the Wells and Geneva scores combined with a standard D-dimer cut-off of 500 ng/mL with three different approaches: age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off, YEARS and PEGeD algorithms. The second outcome was to determine the diagnostic yield of CTPA for PE and to evaluate the diagnostic performance of different D-dimer thresholds to predict PE.

2. Methods

This was a single-centre retrospective study performed at a tertiary hospital (Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte, Lisbon, Portugal) from 1st April 2020 to 31st January 2021. We selected consecutive adult outpatients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to the ED who underwent CTPA due to PE suspicion. Only patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the previous ten days before the ED admission were included. The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection was based on a positive result of real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay of nasopharyngeal and pharyngeal swabs or, in patients with prior diagnosis, by consulting the national registration platform of COVID-19 patients. Patients were excluded if they did not have a D-dimer assay or if CTPA was inconclusive.

Demographic, clinical and laboratory data were collected by an investigator blinded for CTPA reports.

Due to the retrospective analysis of data, the need for informed consent was waived by our institution. Neither patients nor the public were involved in the design, conduct or reporting of our research.

2.1. CT protocol

Computed tomography (CT) was obtained with a 16-slice multi-detector CT (Siemens®) after intravenous injection of 60 to 90 mL of iodinated contrast agent. The CTPA scans were interpreted by the attending radiologist and reviewed at the time of inclusion in the study by a second radiologist, who was blinded for the clinical information.

Pulmonary embolism diagnosis was based on filling defects of the pulmonary artery on at least two consecutive axial sections. In addition, PE was classified according to the location of the thrombus and the presence of right heart strain (defined as right /left ventricle ratio > 1 or interventricular septal bowing).

2.2. Scores and algorithms assessment

The items comprising the diagnostic prediction rules were calculated post hoc by the authors based on the clinical data records at the time of CTPA request. If there was no documentation for a component of any score it was considered absent.

The Wells score ranges from 0 to 12.5 points, based on the following criteria: signs and symptoms of deep vein thrombosis (3 points), PE as the first diagnosis or equally likely (3 points), previous objectively diagnosed PE or deep venous thrombosis (1.5 points), heart rate > 100 beats per minute (1.5 points), immobilization for at least three days or surgery in the previous four weeks (1.5 points), malignancy with treatment within six months or palliative (1 point) and haemoptysis (1 point) [9]. PE was considered equally likely based on the attendant physician's impression recorded in the medical chart. Patients were categorized as having low (<4.0 points), moderate (4.5–6.0 points) or high (≥6.5 points) pretest probability of PE.

The revised Geneva score (GENEVA) considers the following: previous objectively diagnosed PE or deep vein thrombosis (3 points), unilateral lower limb pain (3 points), heart rate > 95 or between 75 and 94 beats per minute (5 and 3 points, respectively), active malignant condition (2 points), haemoptysis (2 points), age > 65 years (1 point) and pain on limb palpation (4 points) [9]. Patients were categorized as having low (0–3 points), moderate (4–10 points) or high (≥11 points) clinical probability of PE.

In the standard approach, patients classified as high clinical probability on Wells or Geneva scores are selected to perform CTPA. In contrast, patients with low to moderate clinical probability perform CTPA if they have a D-dimer value above 500 ng/mL or above their individual cut-off if an age-adjusted approach was considered. The age-adjusted D-dimer threshold was defined by multiplying the patients' age by ten in patients above 50 years old [10].

The YEARS algorithm is based on D-dimer levels and three clinical variables: haemoptysis, signs or symptoms of deep vein thrombosis and whether PE is the most likely diagnosis [7]. PE is excluded in patients with 0 YEARS items and a D-dimer level less than 1000 ng/mL or in patients with one or more YEARS items and a D-dimer level less than 500 ng/mL. All other patients should perform CTPA.

In the PEGeD algorithm, PE is ruled out in patients with low pretest probability and a D-dimer level of less than 1000 ng/mL or with a moderate pretest probability and a D-dimer level of less than 500 ng/mL8. All other patients, including those with high clinical probability, should perform CTPA. Pretest clinical probability in this algorithm is based on Wells score described above.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as frequency rates and percentages and continuous variables as median with interquartile range. Categorial and continuous variables were compared using Pearson chi-square and Mann-Whitney tests, respectively. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, likelihood ratios and diagnostic odds ratio were calculated and compared among the different diagnostic prediction rules. The discriminative power of each score to predict PE was determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated.

Statistical significance was defined as a P value <0.05. The statistical software used to analyse the data was SPSS®v.26 (IBM).

3. Results

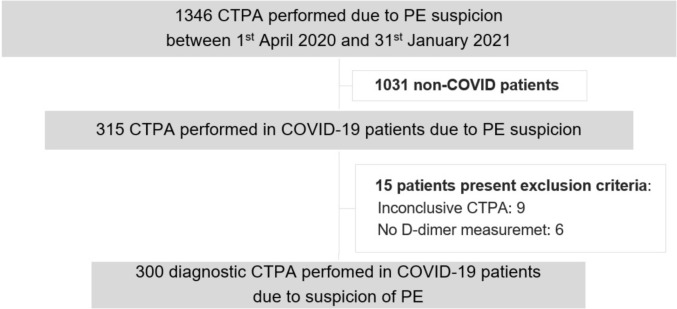

A total of 1346 CTPAs were performed due to PE suspicion during the study period, 315 of them in patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. The study flowchart is summarized in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart. Abbreviations: CT, Computed tomography; PA, pulmonary angiography; PE, pulmonary embolism.

The demographic, clinical and laboratory features of patients with and without PE are shown in Table 1 . CTPA confirmed PE in 46 patients (15%). The vascular allocation of emboli showed a predominantly central distribution (59%), affecting main and lobar arteries (15% and 44%, respectively). Most PE had bilateral involvement (57%) and 22% of patients had evidence of right heart strain. Thrombolytic therapy was not performed in any patient. Notably, PE was documented in three patients under anticoagulation (1 patient with lobar and 2 with subsegmental involvement), two of those died during hospitalization.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and clinical characteristics of patients admitted with COVID-19 and PE suspicion at baseline (all patients) and according to the outcome (with or without pulmonary embolism). Data are reported as n (%) or median (IQR). Abbreviations: PE, pulmonary embolism; ED, emergency department; RT-PCR, real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro hormone B-type natriuretic peptide; ICU, intensive care unit.

| Variable | PE patients (n = 46) | Non-PE patients (n = 254) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (Q1–13) (years) | 76 | (65–84) | 71 | (60–81) | p = 0.044 |

| Gender - Male, n (%) | 22 | (47.8%) | 154 | (60.6%) | p = 0.105 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Obesity, n (%) | 5 | (10.9%) | 47 | (18.5%) | p = 0.208 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 27 | (58.7%) | 150 | (59.1%) | p = 0.964 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 14 | (30.4%) | 81 | (31.9%) | p = 0.845 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 11 | (23.9%) | 72 | (28.3%) | p = 0.536 |

| Chronic heart failure, n (%) | 2 | (4.3%) | 23 | (9.1%) | p = 0.392 |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 6 | (13.0%) | 21 | (8.3%) | p = 0.274 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 3 | (6.5%) | 24 | (9.4%) | p = 0.779 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 19 | (41.3%) | 81 | (31.9%) | p = 0.213 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 9 | (19.6%) | 34 | (13.4%) | p = 0.271 |

| Chronic respiratory insufficiency, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 3 | (1.2%) | p = 1.000 |

| Apnea syndrome, n (%) | 1 | (2.2%) | 16 | (6.3%) | p = 0.486 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 7 | (15.2%) | 32 | (12.6%) | p = 0.627 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 6 | (13.0%) | 21 | (8.3%) | p = 0.277 |

| Active malignancy, n (%) | 2 | (4.3%) | 18 | (7.1%) | p = 0.749 |

| ED presentation | |||||

| Progressive dyspnea, n (%) | 27 | (58.7%) | 172 | (67.7%) | p = 0.234 |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 8 | (17.4%) | 55 | (21.7%) | p = 0.514 |

| Chest pain, n (%) | 7 | (15.2%) | 35 | (13.8%) | p = 0.796 |

| Syncope, n (%) | 3 | (6.5%) | 12 | (4.7%) | p = 0.710 |

| Dry cough, n (%) | 13 | (28.3%) | 103 | (40.6%) | p = 0.115 |

| Fever, n (%) | 12 | (26.1%) | 76 | (29.9%) | p = 0.599 |

| Altered mental status, n (%) | 9 | (19.6%) | 26 | (10.2%) | p = 0.070 |

| Hemoptysis, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 3 | (1.2%) | p = 1.000 |

| Systolic blood pressure, median (Q1–Q3) (mmHg) | 133 | (119–143) | 127 | (114–140) | p = 0.157 |

| Heart rate, median (Q1-Q3) (beats/min) | 85 | (79–100) | 88 | (75–101) | p = 0.686 |

| Respiratory rate, median (Q1-Q3) (breaths/min) | 16 | (16–18) | 18 | (16–20) | p = 0.214 |

| SpO2, median (Q1-Q3) (%) | 95 | (92–98) | 95 | (92–97) | p = 0.544 |

| Oxygen apport, median (Q1-Q3) (L/min) | 0.5 | (0–3) | 0 | (0–3) | p = 0.681 |

| Temperature, median (Q1-Q3) (°C) | 37.0 | (36.2–37.5) | 36.8 | (36.2–37.6) | p = 0.636 |

| Time between COVID-19 symptoms and CTPA, median (Q1-Q3) (days) | 4 | (1–8) | 4.5 | (2–9) | p = 0.370 |

| RT-PCR positive to CTPA, median (Q1-Q3) (days) | 3 | (0–10.5) | 1 | (0–6) | p = 0.130 |

| Ambulatory treatment with: | |||||

| Estrogen use, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | NA |

| Anticoagulation, n (%) | 3 | (6.5%) | 26 | (10.2%) | p = 0.434 |

| Laboratory results | |||||

| Hemoglobin, median (Q1-Q3) (g/dL) | 13.0 | (12.0–14.0) | 13.6 | (12.7–14,5) | p = 0.051 |

| D-dimer, median (Q1-Q3) (ng/mL) | 5880 | (1170–22,000) | 1400 | (800–2820) | p < 0.001 |

| Platelets, median (Q1-Q3) (x103) | 209 | (149–250) | 218 | (168–279) | p = 0.483 |

| hs Troponin T, median (Q1-Q3) (ng/L) | 29 | (19–125) | 15 | (9–32) | p = 0.002 |

| NT-proBNP, median (Q1-Q3) (pg/mL) | 652 | (260–4754) | 423 | (106–1315) | p = 0.038 |

| Creatinine, median (Q1-Q3) (mg/dL) | 0.99 | (0.81–1.25) | 0.97 | (0.81–1.26) | p = 0.651 |

| eGFR, median (Q1-Q3) (mL/min/1.73m2) | 67 | (50–83) | 74 | (50–90) | p = 0.122 |

| Clinical outcomes | |||||

| Hospitalization, n (%) | 44 | (95.7%) | 205 | (80.7%) | p = 0.013 |

| ICU admission, n (%) | 4 | (8.7%) | 45 | (17.7%) | p = 0.281 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 3 | (6.5%) | 33 | (13.0%) | p = 0.417 |

| Death, n (%) | 12 | (26.1%) | 57 | (22.4%) | p = 0.795 |

Despite being older, PE patients did not differ from non-PE patients regarding comorbidities, traditional risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and signs and symptoms at the ED presentation.

Although elevated in all patients, those with PE had higher D-dimer levels compared with non-PE patients. Furthermore, PE patients also showed significantly higher levels of cTnT-hs and NT-proBNP.

In univariate analysis, only age (OR: 1.024, 95% CI 1.002–1.047, p = 0.036), D-dimer levels (OR: 1.018, 95% CI 1.004–1.031, p = 0.010) and cTnT-hs (OR: 1.007, 95% CI 1.002–1.012, p = 0.011) were identified as predictors of PE occurrence. None of the comorbidities or traditional risk factors for VTE were identified as PE predictors in this cohort.

Considering adverse clinical outcomes, PE occurrence was an independent predictor of hospitalization (OR: 5.259, 95% CI 1.232–22.438, p = 0.025), but it had no predictive value for intensive care unit admission (OR: 0.442, 95% CI 0.151–1.296, p = 0.137), mechanical invasive ventilation (OR: 0.467, 95% CI 0.137–1.592, p = 0.224) or death (OR 1.378, 95% CI 0.700–2.713, p = 0.353).

3.1. D-dimer performance

Table 2 shows the diagnostic performance and number of CTPAs correctly avoided in our cohort when progressively higher D-dimer cut-offs were applied. The use of a cut-off of 1000 ng/mL was associated with a significant increase in specificity and a non-significant decrease in sensitivity compared with a cut-off of 500 ng/mL (p < 0.001 and p = 0.063, respectively), although it was associated with five more missed PE diagnosis. On the other hand, the cut-offs of 2590 ng/mL, 2669 ng/mL and 2903 ng/mL, proposed in previous studies, were all associated with a significant decrease in sensitivity and increase in specificity compared to the cut-off of 500 ng/mL (p < 0.001 for all).

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity and negative predictive value of each D-Dimer threshold and the correspondent number of CTPA correctly avoid and missed diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Abbreviations: NPV, negative predictive value; CT, computed tomography; PA, pulmonary angiography; PE, pulmonary embolism.

| D-dimer threshold (ng/mL) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | NPV | Correctly avoid CTPA | Missed PE diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 95.65 [85.16–99.47] | 8.66 [5.51–12.82] | 91.67 [73.00–98.97] | 22 | 2 |

| 1000 | 84.78 [71.13–93.66] | 33.46 [27.69–39.63] | 92.39 [84.95–96.89] | 85 | 7 |

| 2590 [Mouhatet al.] [11] | 58.70 [43.23–73.00] | 72.44 [66.51–77.84] | 90.64 [85.77–94.27] | 184 | 19 |

| 2660 [Leonard-Lorant et al.] [12] | 58.70 [43.23–73.00] | 73.23 [67.34–78.57] | 90.73 [85.90–94.33] | 186 | 19 |

| 2903 [Ventura-Díaz et al.] [13] | 56.52 [41.11–71.07] | 76.77 [71.08–81.82] | 90.70 [86.00–94.22] | 195 | 20 |

Table 3 illustrates the accuracy of the different diagnostic prediction rules for PE.

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of Wells and Geneva scores combined with a fixed and an age-adjusted cut-off, YEARS algorithm and PEGeD algorithm to predict pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients. Abbreviations: DD, D-dimer; AUC, area under the curve.

| Wells score + DD threshold of 500 ng/mL | Geneva score + DD threshold of 500 ng/mL | Wells score + age-adjusted DD cut-off | Geneva score + age-adjusted DD cut-off | YEARS algorithm | PEGeD algorithm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % | 95.65 [85.16–99.47] | 95.65 [85.16–99.47] | 89.13 [76.43–96.38] | 89.13 [76.43–96.38] | 86.96 [73.74–95.06] | 84.78 [71.13–93.66] |

| Specificity, % | 8.27 [5.19–12.36] | 8.27 [5.19–12.36] | 15.35 [11.15–20.39] | 15.35 [11.15–20.39] | 31.10 [25.46–37.19] | 31.23 [25.57–37.33] |

| Positive predictive value, % | 15.88 [11.79–20.73] | 15.88 [11.79–20.73] | 16.02 [11.74–21.09] | 16.02 [11.74–21.09] | 18.60 [13.64–24.46] | 18.31 [13.36–24.17] |

| Negative predictive value, % | 91.30 [71.96–98.93] | 91.30 [71.96–98.93] | 88.64 [75.44–96.21] | 88.64 [75.44–96.21] | 92.94 [85.27–97.37] | 91.86 [83.95–96.66] |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 1.04 [0.97–1.12] | 1.04 [0.97–1.12] | 1.05 [0.94–1.18] | 1.05 [0.94–1.18] | 1.26 [1.10–1.45] | 1.23 [1.06–1.43] |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.53 [0.13–2.17] | 0.53 [0.13–2.17] | 0.71 [0.29–1.70] | 0.71 [0.29–1.70] | 0.42 [0.19–0.90] | 0.49 [0.24–0.99] |

| Diagnostic odds ratio | 1.98 [0.45–8.76] | 1.98 [0.45–8.76] | 1.49 [0.55–4.00] | 1.49 [0.55–4.00] | 3.01 [1.23–7.39] | 2.53 [1.08–5.90] |

| AUC | 0.520 [0.431–0.608] | 0.520 [0.431–0.608] | 0.521 [0.432–0.610] | 0.521 [0.432–0.610] | 0.589 [0.506–0.672] | 0.580 [0.496–0.664] |

| Correctly avoided CTPA, n | 21 | 21 | 39 | 39 | 79 | 79 |

| Missed PE diagnosis, n | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

3.2. Wells and Geneva scores

The prevalence of risk factors for VTE in patients with or without PE is represented in Table 4 . No differences were found in Wells and Geneva scores and traditional risk factors between groups. Regarding patients with PE, 95.7% was considered as having low probability by Wells score. In addition, according to Wells or Geneva score, none of the patients was classified as having a high probability of PE. Thus, these scores shown no predictive value for PE occurrence (OR: 1.084, 95% CI 0.841–1.396, p = 0.533; OR: 1.023, 95% CI 0.869–1.205, p = 0.784, respectively).

Table 4.

Risk assessment for pulmonary embolism according to Wells score, Geneva score and YEARS algorithm and prevalence of each risk factor. Abbreviations: PE, pulmonary embolism; DVT, deep vein thrombosis. a – variables included in Geneva score; b – variables included in Wells score; c- variables included in the YEARS items

| Variable | PE patients (n = 46) | Non-PE patients (n = 254) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wells score | |||||

| Median, (Q1–Q3) (pts) | 0 (0–1.5) | 0 (0–1.5) | p = 0.749 | ||

| Probability of PE according to score | |||||

| Low risk, n (%) | 44 | (95.7%) | 245 | (96.5%) | p = 0.790 |

| Moderate risk, n (%) | 2 | (4.3%) | 9 | (3.5%) | p = 0.790 |

| High risk, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | NA |

| Revised Geneva score | |||||

| Median, (Q1–Q3) (pts) | 4 (3–5.25) | 4 (3–5) | p = 0.878 | ||

| Probability of PE according to score | |||||

| Low risk, n (%) | 13 | (28.3%) | 89 | (35%) | p = 0.373 |

| Moderate risk, n (%) | 33 | (71.7%) | 165 | (65%) | p = 0.373 |

| High risk, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 0 | (0%) | NA |

| YEARS items | |||||

| 0 items, n (%) | 41 | (89.1%) | 235 | (92.5%) | p = 0.388 |

| ≥1 item, n (%) | 5 | (10.9%) | 19 | (7.5%) | p = 0.388 |

| Components of the scores | |||||

| Age > 65 years a, n (%) | 34 | (73.9%) | 161 | (63.4%) | p = 0.168 |

| Previous diagnosis of DVT/PE a,b, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 5 | (2.0%) | p = 1.0 |

| Clinical signs of DVT b,c, n (%) | 1 | (2.2%) | 3 | (1.2%) | p = 0.488 |

| Malignancy b, n (%) | 2 | (4.3%) | 18 | (7.1%) | p = 0.749 |

| Heart rate > 100 beats per minute b, n (%) | 12 | (26.1%) | 70 | (27.6%) | p = 0.837 |

| Heart rate > 95 beats per minute a, n (%) | 13 | (28.3%) | 88 | (34.6%) | p = 0.399 |

| Heart rate 75–94 beats per minute a, n (%) | 24 | (52.2%) | 108 | (42.5%) | p = 0.225 |

| Surgery or fracture within 1 month a, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (0.4%) | p = 1.0 |

| Immobilization for 3 days or surgery in 4 weeksb, n(%) | 4 | (8.7%) | 11 | (4.3%) | p = 0.260 |

| Unilateral leg edema a, n (%) | 2 | (4.3%) | 2 | (0.8%) | p = 0.113 |

| Unilateral leg pain a, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (0.4%) | p = 1.0 |

| Hemoptysis b,c, n (%) | 0 | (0%) | 3 | (1.2%) | p = 1.0 |

| PE as the first diagnosis or equally likely b,c, n (%) | 4 | (8.7%) | 14 | (5.5%) | p = 0.495 |

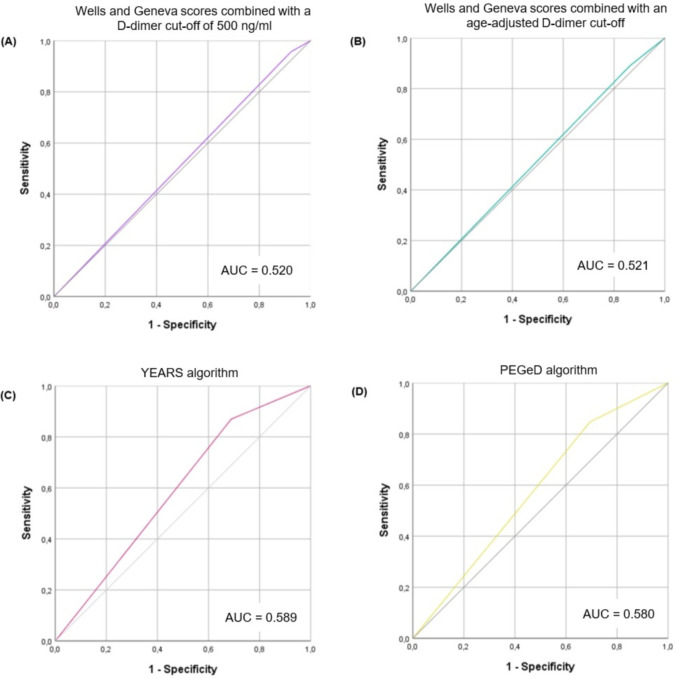

Twenty-one patients had a D-dimer value higher than the fixed D-dimer threshold of 500 ng/mL but lower than their age-adjusted cut-off. Among those patients, 3 had PE (2 patients with lobar and one patient with subsegmental involvement). When pretest clinical probability was combined with an age-adjusted cut-off, it resulted in lower sensitivity than the standard threshold of 500 ng/mL, although it was not statically significant (89.13% vs 95.65%, p = 0.250). Regarding specificity, an age-adjusted cut-off resulted in a substantial increase in specificity compared to the standard cut-off (15.35% vs 8.27%, respectively, p < 0.001). The AUC for both Wells and Geneva scores combined with a cut-off of 500 ng/mL and an age-adjusted cut-off (Fig. 2A and B) suggests nearly no discriminative power.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve demonstrating the diagnostic performance of different decision rules to predict the risk of pulmonary embolism (PE) in COVID-19 patients with PE suspicion. A, Wells and Geneva score combined with a fixed D-dimer cut-off of 500 ng/ml; B, Wells and Geneva score combined with an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off; C, YEARS algorithm; D, PEGeD algorithm.

3.3. YEARS algorithm

The YEARS algorithm had a significantly higher specificity than a D-dimer cut-off of 500 ng/mL or age-adjusted, whether Wells or Geneva scores were used to evaluate pretest probability (p < 0.001 for both). Regarding sensitivity, the YEARS algorithm was non-inferior to a 500 ng/mL cut-off or an age-adjusted cut-off (p = 0.150 and p = 1.0, respectively). However, even though the decrease in sensitivity was not statistically significant, the YEARS algorithm was associated with four more missed PE diagnoses than the D-dimer cut-off of 500 ng/mL.

3.4. PEGeD algorithm

Although not statistically significant, the PEGeD algorithm had the lowest sensitivity of all diagnostic prediction rules considered (p = 0.063 for a D-dimer cut-off of 500 ng/mL; p = 0.50 for an age-adjusted cut-off; and p = 1.00 for YEARS algorithm). PEGeD algorithm was associated with five more missed PE diagnoses than the D-dimer cut-off of 500 ng/mL. The PEGeD algorithm had a significantly higher specificity than a fixed and an age-adjusted D-dimer cut-off (p < 0.001 for both). There was no difference regarding sensitivity and specificity between YEARS and PEGeD algorithms (p = 1.00 for both).

In summary, none of the diagnostic strategies was significantly superior regarding sensitivity compared to each other (p > 0.06 for all). However, an age-adjusted approach had a significantly higher specificity than a fixed D-dimer threshold of 500 ng/mL, whether clinical probability was evaluated by Wells or Geneva scores (p < 0.001 for all). YEARS and PEGeD algorithms had higher specificity compared to an age-adjusted approach (p < 0.001 for both). Lastly, there was no difference regarding specificity between YEARS and PEGeD algorithms (p = 1.0).

4. Discussion

Since the first reports, PE was described as one of the most common complications of SARS-COV-2 infection [4,5]. This study showed a diagnostic yield of 15% in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection that underwent a CTPA due to PE suspicion. Except for older age, we found no differences regarding comorbidities, traditional risk factors for VTE and signs and symptoms at presentation between patients with and without PE.

Wells and Geneva scores have been used for decades to predict PE. Currently, the need for CTPA is determined by combining the clinical probability with D-dimer levels [9]. However, considering that COVID-19 patients have a different thrombotic and inflammatory milieu, the usefulness of these prediction rules for PE in this condition is a matter of debate. Previous studies demonstrated no differences between patients with and without PE regarding traditional risk factors for VTE [11,[14], [15], [16]]. Furthermore, Whyte M.B. et al. showed no difference in Wells score between those with and without PE in a cohort of 214 patients that performed CTPA due to PE suspicion [14]. Consistent with these reports, we found that neither the Wells nor Geneva scores were higher in COVID-19 patients with PE than those without PE. This finding highlights the importance of the association between the induced COVID-19 hyperinflammatory status and a thrombotic outcome [17].

Pulmonary embolism was detected in 15% and 13% of patients considered as having low probability by Wells and Geneva scores, respectively, which is much higher than the 1 to 3% rate expected from the literature in non-COVID patients [18,19]. Moreover, 95.7% of PE patients were considered as having low probability by Wells score (58.7% of those with a Wells score of 0 pts). We demonstrated that even when clinical pretest probability, evaluated by these scores, was combined with the D-dimer measurement, the discriminative power to predict PE in COVID-19 patients remains low.

According to the international guidelines for diagnosing and managing PE, the YEARS and PEGeD algorithms should be considered as an alternative to the standard approach to rule out PE [9]. The main advantage of these scores is their ability to safely reduce CTPA requests by adjusting the D-dimer cut-off to the clinical probability. To the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to compare these new proposed algorithms' diagnostic performance with the standard approach based on Wells or Geneva scores to predict PE in COVID-19 patients. These algorithms were associated with an absolute reduction of 19.3% in the number of CTPA. However, they were also associated with decreased sensitivity that, although not statistically significant, is clinically relevant.

In agreement with previous studies, we found that PE patients had significantly higher D-dimer levels than non-PE patients [12,20]. Considering that COVID-19 patients tend to have higher D-dimer levels even in the absence of PE, several authors proposed higher D-dimer thresholds to select patients for CTPA, based on maximizing the Youden index [[11], [12], [13]]. However, considering that the D-dimer is used as a triage test, the safety of this diagnostic approach is questionable. Mouhat B et al. proposed a D-dimer cut-off value of 2590 ng/mL to best predict PE occurrence in COVID-19 patients, which is slightly lower than the suggested by Ventura-Díaz et al. (2903 ng/mL) [11,13]. With the cut-offs above mentioned, the authors reported a sensitivity of 83% and 81%, respectively, being far from the pretended negative predictive value of 100% for a triage test. As represented in Table 2, when these cut-offs were applied to our cohort, we found an unacceptably low sensitivity, despite allowing a reduction of up to 68% in CTPAs. Considering the clinical implications of a missed PE diagnosis, defining a D-dimer threshold according to a higher negative predictive value might be more acceptable than adjusting the D-dimer threshold to increase specificity. Our results suggest that the 500 ng/mL cut-off point might be the safer strategy in COVID-19 patients. We found no difference in clinical presentation between patients with or without PE, which is in line with the previous reported [14,15,21,22].

Patients with PE had significantly higher cTnT-hs and NTpro-BNP levels than those without PE. Although this finding is consistent with the reported in a cohort of 162 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 that performed CTPA [23], other studies found no difference concerning cardiac biomarkers between patients with or without PE [15,16,24]. A higher incidence of central PE can explain our findings compared to those studies.

In our cohort, PE was not associated with higher mortality. This finding is consistent with a French multicentre cohort of 1204 patients, although other studies documented otherwise [25,26]. This could be related to the heterogeneity of the severity of the concomitant COVID- 19 disease.

According to the European Society of Cardiology recommendations in COVID-19, PE diagnosis in these patients should be based on algorithms combining pretest clinical probability with D-dimer [27]. These recommendations suggest that an unexpected respiratory worsening, signs of deep vein thrombosis, hypotension not attributable to other causes and a new or unexpected tachycardia may trigger the suspicion of PE. Although this is true for the general population, COVID-19 population seems to break the rule.

We demonstrated a remarkable absence of the usual comorbidities, typical VTE risk factors and overlap of signs and symptoms between PE and non-PE COVID-19 patients, which acknowledge recent published data. These findings reinforce the difficulty of PE diagnosis in COVID-19 patients and claims in favour of a different screening strategy. However, the use of higher D-dimer thresholds does not seem to be the solution to improve the diagnostic accuracy for PE in these patients, as it limits this strategy as a screening test.

4.1. Limitations

Our study has some limitations. It was a retrospective single-center and chart review study. One of the most relevant limitations of this study design is determining clinician judgement by reading a note rather than seeing the patient. Additionally, patients were included if a CTPA was performed in the ED, limiting our ability to conclude whether these results can be applied to the whole ED population with PE suspicion.

5. Conclusion

This study suggests that neither Wells and Geneva scores nor the YEARS or PEGeD algorithms are reliable predictors of PE in COVID-19 patients admitted to the ED. Additionally, our data discourages the use of progressive increment in the D-dimer threshold as it limits this strategy as a screening test. These data reinforces the need of further studies to determine specific risk factors and biomarkers to develop more accurate risk-stratification scores for pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients. Meanwhile, the use of CTPA should be encouraged in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection who present with clinical suspicion of PE.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China. N Engl J Med. 2019;2020:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bs M.S., Lal A., Estrada-y-martin R.M. Wells score to predict pulmonary embolism in patients with coronavirus disease-2019. Am J Med. 2021;134:688–690. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.10.044. Elsevier Inc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young Joo S., Hyunsook H., Ohana M., et al. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2021;298:E70–E80. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020203557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., Van Der Meer N.J.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brito J., Silva B.V., Alves P., et al. Vol. 4. 2020. Cardiovascular Complications of COVID - 19; pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Hulle T., Cheung W.Y., Kooij S., et al. Simplified diagnostic management of suspected pulmonary embolism (the YEARS study): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390:289–297. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearon C., de Wit K., Parpia S., et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with d -dimer adjusted to clinical probability. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2125–2134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1909159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konstantinides S.V., Meyer G., Becattini C., et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European respiratory society (ERS) Eur Heart J. 2019;00:1–61. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Righini M., Van Es J., Den Exter P.L., et al. Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to rule out pulmonary embolism: the ADJUST-PE study. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:1117–1124. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouhat B., Besutti M., Bouiller K., et al. Elevated D-dimers and lack of anticoagulation predict PE in severe COVID-19 patients. Eur Respir J. 2020;56 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01811-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Léonard-Lorant I., Delabranche X., Séverac F., et al. Acute pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 at CT angiography and relationship to d-dimer levels. Radiology. 2020;296:E189–E191. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ventura-díaz S., Quintana-pérez J.V., Gil-boronat A., et al. A higher D-dimer threshold for predicting pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study. Emerg Radiol. 2020;27:679–689. doi: 10.1007/s10140-020-01859-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whyte M.B., Kelly P.A., Gonzalez E., et al. Pulmonary embolism in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;195:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.07.025. Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alonso-Fernández A., Toledo-Pons N., Cosío B.G., et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and high D-dimer values: a prospective study. PLoS One. 2020;15:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fauvel C., Weizman O., Trimaille A., et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: a French multicentre cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3058–3068. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-ortega A., Oscullo G., Calvillo P., et al. Incidence, risk factors, and thrombotic load of pulmonary embolism in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection. J Infect. 2021;82:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ceriani E., Combescure C., gal G Le, et al. Clinical prediction rules for pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:957–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iles S., Hodges A.M., Darley J.R., et al. Clinical experience and pre-test probability scores in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. QJM - Mon J Assoc Physicians. 2003;96:211–215. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bompard F., Monnier H., Saab I., et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2020;56 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01365-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gervaise A., Bouzad C., Peroux E., et al. Acute pulmonary embolism in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients referred to CTPA by emergency department. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:6170–6177. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06977-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freund Y., Drogrey M., Miró Ò., et al. Association between pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 in emergency department patients undergoing computed tomography pulmonary angiogram: the PEPCOV international retrospective study. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27:811–820. doi: 10.1111/acem.14096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mouhat B., Besutti M., Bouiller K., et al. Elevated D-dimers and lack of anticoagulation predict PE in severe COVID-19 patients. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:1–11. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01811-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J., Wang X., Zhang S., et al. Characteristics of acute pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia from the City of Wuhan. Clin Appl Thromb. 2020;26 doi: 10.1177/1076029620936772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scudiero F., Silverio A., Di Maio M., et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: prevalence, predictors and clinical outcome. Thromb Res. 2021;198:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malas M.B., Naazie I.N., Elsayed N., et al. Thromboembolism risk of COVID-19 is high and associated with a higher risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine Elsevier Ltd. 2020;29–30:100639. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.European Society of Cardiology ESC Guidance for the Diagnosis and Management of CV Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur Heart J. 2020:1–115. [Google Scholar]