Abstract

Flood relief and rescue form an important basis of disaster management, and the assessment of flood damage is a critical component of flood risk management. In its recent history, Kashmir Valley witnessed the floods in 2014, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2020, and 2021, but the worst flood in the living memory of the people was witnessed in the year 2014, which created widespread loss in economic and societal aspects. The present study discusses the spatial dimension of impact, relief, and rescue of the flood of 2014 in the Kashmir Valley. It analyses the distribution of relief and politics of relief and rescue and highlights the role of the communitarianism and the heroics of the community members in dealing with floods. The study provides the data of relief distribution under different government schemes and reveals that the relief was not distributed equally in various districts of the valley. The study relies on primary and secondary sources of data. Ethnographic approach was used for acquiring primary data because it provides the complex narratives of disasters and the political and social rupture experienced during the disasters. The data have been analysed with the help of Geographic Information System.

Keywords: Flood relief, Politics, Communitarianism, Kashmir, Relief Deprivation Index

Introduction

Disasters are the aberrations from the normal life. Floods are widely regarded as the most devastating and recurring cause of most disasters, wreaking havoc on floodplain dwellers around the world (Dhar and Nandargi 2003). Floods are responsible for one-third of all hydrological hazards on the earth (Adhikari et al. 2010). River flooding is one of the most devastating disasters in the world, causing widespread loss of life, infrastructure damage, and economic devastation. Societies are currently under threat from such floods, owing primarily to increased exposure of people and assets in flood prone areas, but also to changes in flood magnitude, frequency, and timing (Wilhelm et al. 2019).

Floods affect billions of people around the world (Zarekarizi et al. 2020). Between 2009 and 2019, floods killed around 50,000 people and affected approximately 10% of the world's population, according to the Emergency Events Database (CRED 2019). Floods are expected to become more frequent and widespread as a result of population growth and climate change (Leung et al. 2019). The global disaster dataset reveals that the number of disasters, especially floods, has increased in recent times and South Asia has seen a dramatic increase in flood disasters (Saharia et al. 2021). In a global survey of disasters, Jonkman (2005) found that Asian rivers are the most significant in terms of the number of persons killed and affected, with flash floods resulting in the highest average death per incident. The damage to crops, infrastructure, and housing, and the negative impacts on health and sanitation caused by floods are particularly severe in the populous floodplains of many Third World states (Alexander 2018).

The Kashmir Valley is vulnerable to all types of hazards due to its geographical, climatic, and geological configuration (Meraj et al. 2015). According to historical records, the Kashmir Himalayan region has suffered significant casualties and property loss as a result of recurring floods, avalanches, earthquakes, and several other hydro-meteorological disasters (Mohammed et al. 2015). Because of the valley's topography, low-lying areas are prone to flooding. In recent years, unchecked urbanization, the construction of roads and railways in the flood basin, a reduction in river carrying capacity, and the accelerated extinction of the valley's wetlands and lakes have exacerbated the valley's flood vulnerability (Iqbal 2019), thus causing several floods. Floods devastated the Kashmir Valley in 1893, 1928, 1950, 1959, 1992, 2010, and most recently in 2014, 2015, 2017, and 2019. All of these floods had varying effects, but the flood of 2014 was the most destructive flood in the recent history of Kashmir, affecting all socioeconomic and environmental aspects as well as causing political rupture in the Valley (Malik and Hashmi 2020).

The catastrophic flood event of 2014, which was the biggest ever recorded on the river Jhelum and resulted in massive losses of assets and human life, is a recent example of the Kashmir basin's vulnerability to floods (Mishra 2015; Bhatt et al. 2017). The Kashmir flood of September 2014 inundated the majority of the floodplain in Kashmir, resulting in massive loss of life and property. The magnitude of this event was declared to be the highest ever instrumentally recorded on the Jhelum River, with an estimated discharge of 1, 15,218 cusecs upstream at Sangam and 72,585 cusecs downstream at Ram Munshi Bagh in Srinagar City. During the flood, highest flood level (HFL) records obtained from a post-flood survey using Global Positioning System (GPS) revealed floodwater depths of up to 16 feet and a 25-day inundation period in various areas of Kashmir (Akhtar Alam et al. 2018).

The 2014 flood in Kashmir Valley had a devastating impact on the socio-economic, environmental, and political conditions in Kashmir. It was the worst flood to strike the Valley in the last 100 years, killing 277 people in Jammu and Kashmir. The relief and rescue efforts were dispersed across the Valley in various districts and thus gave rise to the spatial dimension of such actions.

The present study is significant because it gives a detailed account of relief provided to people under different governmental schemes and also rescue of the 2014 Kashmir flood and fills the research gap regarding relief provided to people. There is a lack of studies on Kashmir floods that give the detailed accounts of rescue and relief operations, and the current study is significant in order to explain the spatial distribution of relief and rescue operations. It explains various narratives witnessed during the flood in the Kashmir Valley and provides a deeper understanding of communitarianism in the Kashmiri society in terms of flood response. It also emphasizes administrative laxity, as well as the bias and politics in rescue and relief operations.

Ethnography is important for understanding how actors in various domains attach meaning to disasters and disaster response, as well as how they influence one another. Ethnography should not be limited to local domains; it can be equally useful and insightful when performed in and between other disaster response domains. It is worthwhile to consider recent developments in ethnography (Hilhorst 2013) to study the flood situations like the recent floods in the Kashmir Valley.

In the light of the above, the study seeks to (1) assess the impact of the 2014 flood in Kashmir Valley, (2) analyse the spatial dimension of rescue and relief operations, (3) highlight the emergence of communitarianism during the floods in the Kashmir valley, and (4) emphasize the politics of rescue and relief.

Data sets and methodology

The current study relies on primary and secondary sources of data. Kashmir Valley has total 10 districts, and from every district 20 households were surveyed, which makes the total sample size as 200. Thus, a total of 200 households were surveyed to know the spatial dimension of impact, relief, and rescue during and after the floods experienced in Kashmir Valley with a special focus on the 2014 flood. The analysis of previous studies and data helped in choosing the sampling method, and thus, the samples were collected with the help of purposive sampling, which helped in acquiring the required information. Ethnographic approach was used to know about different narratives regarding the impact, relief, and rescue operations because ethnography provides the ground reality about social phenomena and the disaster scenario, and the researcher is better able to comprehend the research subjects' experiences and habits from the participant's point of view. The undisguised participant observation ethnographic method was used in which the ethnographer becomes the member of the group, which was also guided by the personal experiences of rescue and relief operations during the 2014 flood. The secondary data were collected from the Divisional Commissioner’s Office, Srinagar. To process the data and create the maps, Arc GIS 10.2 was used.

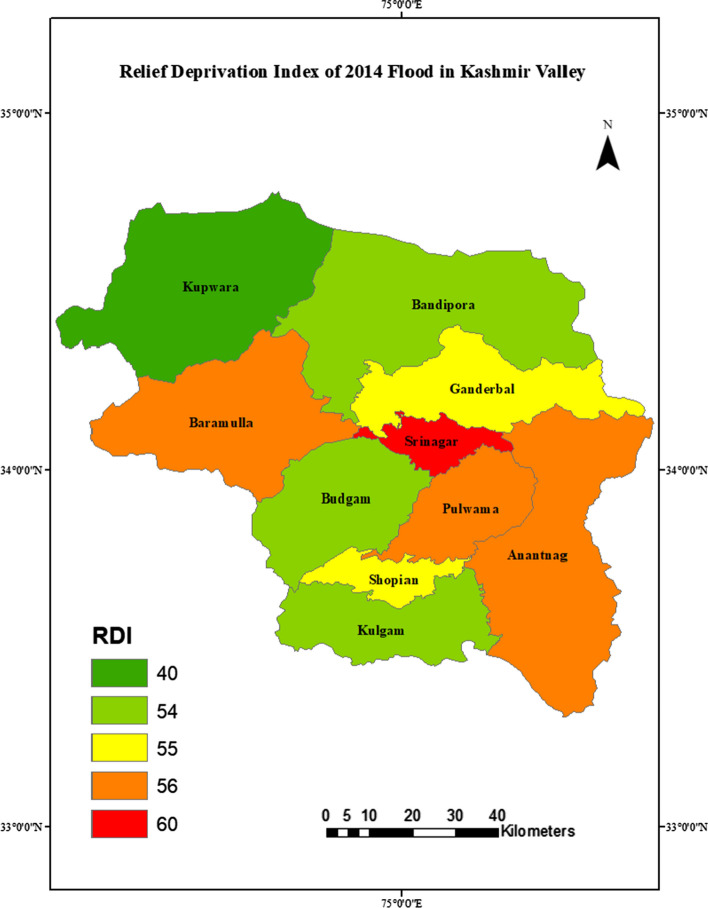

Spatial deprivation is a common form of regional disparity among various axes (Herbert 1975). It implies a direct link between deprivation and regional inequality (Norris 1979). Deprivation is commonly used to denote a lack of something considered necessary for having an acceptable quality of life (Brown and Madge 1982). Taking inspiration from the deprivation index, the Relief Deprivation Index (RDI) was devised for the present study.

The Relief Deprivation Index (RDI) was used to determine the amount of loss and relief received, and the district-wise inequality in terms of relief received. It calculates how much money a household has been deprived of that it should have received. The greater the value of the deprivation index, the greater the level of deprivation. To create a composite deprivation index, researchers used a variety of methodologies. Their methodologies differ in terms of the indicators used. Different deprivation indices are developed to classify all districts in terms of multiple deprivations, and in the present study, the RDI was used to examine the spatial dimension of relief received. Districts with high deprivation index scores have received less relief while as the districts with low deprivation index have received comparatively better relief.

The relief deprivation was calculated by the following formula:

Study area

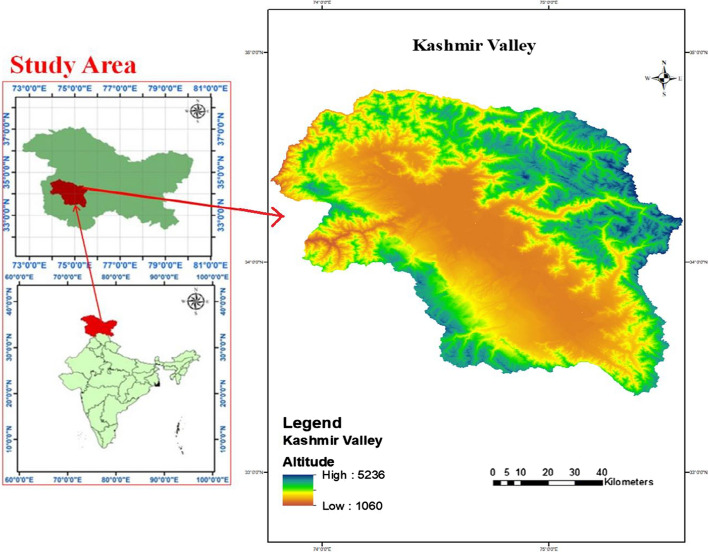

The current study's research area is the Kashmir Valley, which lies in the northern part of India (Fig. 1). It lies in the North-Western Himalayas and comprises of several beautiful valleys and picturesque mountains. It is surrounded by Himalayas from all sides, which has a profound impact on its climate and weather phenomena. The Kashmir Valley has geopolitical significance and is a source of contention among India, China, and Pakistan. It is one of the most volatile conflict regions of the world. The Valley is composed of several beautiful lakes like Wular and Dal lakes and is one of the world's best tourist destinations.

Fig. 1.

Study area (Kashmir Valley)

The Kashmir valley is a 15,220 km2 NW–SE Graben-type basin that formed in the late Miocene (Bhat 1982; Burbank 1983; Alam et al. 2017). The Valley is located in the Jhelum Basin and has a well-developed drainage system led by the Jhelum River. It is surrounded by two major mountain ranges, the Pir Panjal in the south–southwest and the Great Himalaya in the east–northeast (Bhatt et al. 2017).

The 2014 extreme flooding in Kashmir Valley was caused by a complex interplay of atmospheric disturbances that caused widespread extreme rainfall for seven days prior to the event, with a peak discharge of 3,256,437,405,000 cubic mm per second and the Jhelum River overflowing its banks (Romshoo et al 2018). The valley experienced unprecedented rainfall in early September 2014 (September 04–06) as a result of the combined effects of mid-latitude Westerlies and pressure systems typical of the Indian summer monsoon (Kumar and Acharya 2016). Rainfall totals of 415 mm and 140 mm were recorded at Kokernag station in south Kashmir and Rambagh station in Srinagar, respectively, during this time (Ray et al. 2015), resulting in widespread flooding across the valley (Gulzar et al. 2021). Hospitals, communication lines, buildings, water and energy supply facilities, and cultural heritage places all suffered significant damage. The situation triggered an emergency declaration, with over a hundred people killed and thousands of families affected and massive economic loss (Venugopal and Yasir 2017).

Results and discussion

Kashmir Valley witnessed several floods in its recent history. The flooding of September 2014 in Kashmir Valley was anthropogenic in nature rather than a natural calamity. As per the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) (2015), “This is a sentiment so often repeated, that it has taken on the shades of a cliché, with everyone from civil society activists to politicians being in seeming agreement that the Jammu and Kashmir government's administrative laxity and negligence and its peoples' irresponsible development practices were the cause of the floods. Recent understandings of disasters and development, including that of the United Nations, emphasise that human actions and socio-economic inequalities influence the causes of, and vulnerabilities to natural events, and often determine whether a particular 'hazard' takes on disastrous proportions or not”.

Socio-economic impact

Flooding in J&K and Pakistan was the most expensive weather event of 2014 (Annual Global climate and catastrophe report, 2015). Floods in Kashmir in 2014 wreaked havoc on agriculture, trade, infrastructure, tourism, and the handloom sector. According to the government of Jammu and Kashmir, the state suffered a loss of Rs. 1.0 trillion as a result of the floods in September 2014 (Yaseem 2014). The flood had a negative impact on the tourism industry as it is one of the important economic activities in Kashmir Valley (Malik 2015). Over a million people were displaced, and over 3000 settlements were inundated, resulting in a $6560 million economic loss (Carpenter et al. 2020). In terms of cropped area and people affected, the Anantnag district was the worst affected by the flood. The flood affected 153,140 acres of land and 159,507 people in the Anantnag district. It was followed by Baramulla, where the flood affected 132,052 acres of land and 159,200 people. Kupwara was the least affected district in terms of cropped area, with 3218 acres of land affected. The total cropped area affected by the 2014 flood in Kashmir Valley was 694,389 acres, and a total of 906,091 people were affected, excluding the district Srinagar (Malik and Hashmi 2021).

The 2014 flood in Kashmir had disastrous consequences on environment, society, and politics. It created death, poverty, environmental damage, and health problems in the Valley, which resulted into rise of diseases like cholera and malaria.

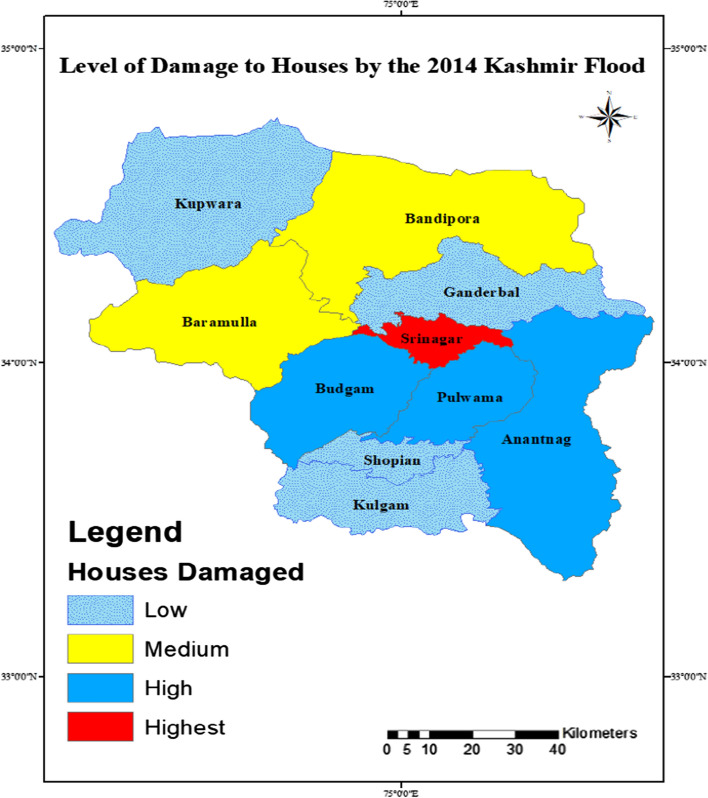

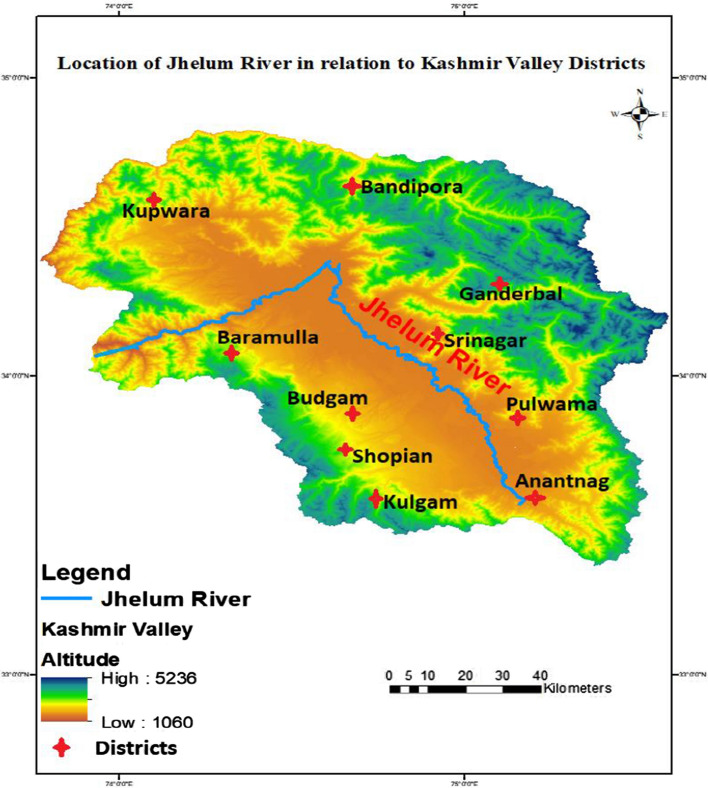

The total number of houses damaged in the Kashmir Valley by the 2014 flood was 167,236 (Table 1, Fig. 2). In terms of house damage, the Srinagar district suffered the most with 93,536 damaged houses, followed by Anantnag (19,985), Budgam (16,963), Pulwama (15,200), Baramulla (8630), Bandipora (7703), Kulgam (3365), Shopian (1336), Ganderbal (429), and Kupwara (89). The damaged houses indicate massive economic and social loss as floods have the intrinsic characteristic of causing socio-economic loss. The districts of the valley were affected differently due to their location in relation to Jhelum River and levels of urbanization. Srinagar and Anantnag districts were affected greatly because these districts lie at the banks of the Jhelum River and are also the most urbanized districts in the Kashmir Valley. As per the 2011 census of India, Srinagar has 95.3% urban population out of its total population and constitutes 61.1% of the total urban population of the Kashmir Valley while as Anantnag has 25.6% urban population out of its total population and constitutes 13.8% of the total urban population of the Kashmir Valley. The percentage of urban population of Srinagar and Anantnag districts is followed by Baramulla (8.3%), Kulgam (3.9%), Pulwama (3.6%), Bandipora (3.2%), Budgam (2.4%), Kupwara (1.6%), Ganderbal (1.4%), and Shopian (0.7%), thus revealing that Srinagar and Anantnag districts are the most urbanized districts in the Kashmir Valley. The location of the districts in relation to the Jhelum River is shown in Fig. 3. Due to high urbanization and poor drainage in the Srinagar city, the water during the flood was accumulated for longer durations and led to the inundation of thousands of houses. Kupwara district was the least affected because it is situated at higher altitude.

Table 1.

Total number of houses damaged in Kashmir Valley due to 2014 flood

| District | Total number of houses damaged |

|---|---|

| Anantnag | 19,985 |

| Bandipora | 7703 |

| Baramulla | 8630 |

| Budgam | 16,963 |

| Ganderbal | 429 |

| Kulgam | 3365 |

| Kupwara | 89 |

| Pulwama | 15,200 |

| Shopian | 1336 |

| Srinagar | 93,536 |

| Total | 167,236 |

Source: Divisional Commissioner’s Office, Srinagar

Fig. 2.

Impact of 2014 flood in Kashmir Valley

Fig. 3.

Location of Jhelum River in relation to Kashmir Valley districts

The 2014 flood in Kashmir Valley had a tremendous impact on the socio-economic aspects in the Valley. The relief deprivation of the surveyed households reveals that most of the people incurred a heavy loss in the form of damage of houses and infrastructure, loss of crops and agricultural land, damage to horticulture and livestock. It also reveals that most of the people did not get adequate relief from the government.

Table 2 and Fig. 4 analysis shows that the highest Relief Deprivation Index was experienced by Srinagar (60%), which means that the Srinagar District has received least relief as districts with high deprivation index scores have received less relief. It was followed by the districts of Anantnag (56%), Pulwama (56%), Baramulla (56%), Ganderbal (55%), Shopian (55%), Bandipora (54%), Kulgam (54%), and lastly Kupwara (40%). These figures show that the people of Kashmir experienced heavy economic loss, which resulted into poverty and economic distress among thousands of people. The economic loss of lower class people, which are mostly engaged in agricultural activities, created food scarcity. It also affected their economic conditions to a great extent as the flood occurred in the month of September 2014 and continued till October, which is the harvesting season in Kashmir. Thousands of families depend on horticulture in Kashmir. The whole agricultural setup including horticulture was adversely affected by the flood and resulted into loss of apple production worth millions of dollars.

Table 2.

Relief Deprivation Index (RDI) of the 2014 Kashmir flood

| S. no. | District | Houses surveyed | Relief received (₹) | Loss (₹) | Ratio (relief/loss) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anantnag | 20 | 3,115,258 | 5,562,962 | 56 |

| 2 | Bandipora | 20 | 2,997,509 | 5,550,943 | 54 |

| 3 | Baramulla | 20 | 3,083,110 | 5,505,555 | 56 |

| 4 | Budgam | 20 | 2,784,565 | 5,156,603 | 54 |

| 5 | Ganderbal | 20 | 2,903,000 | 5,278,181 | 55 |

| 6 | Kulgam | 20 | 2,978,660 | 5,516,037 | 54 |

| 7 | Kupwara | 20 | 2,202,162 | 5,505,405 | 40 |

| 8 | Pulwama | 20 | 2,949,332 | 5,266,666 | 56 |

| 9 | Shopian | 20 | 2,932,000 | 5,330,909 | 55 |

| 10 | Srinagar | 20 | 4,067,796 | 6,779,661 | 60 |

| Total | 200 | 30,013,392 | 55,452,922 | 54 |

Source: Primary survey

Fig. 4.

Relief Deprivation Index (RDI) of the 2014 flood in Kashmir

Abdul Rashid, an apple grower in district Anantnag, while recollecting the memories of the 2014 flood, said “We lost almost one thousand boxes of apples worth one million rupees. We are 10 family members and horticulture is our main source of income. We lost everything in the flood which created a sense of hopelessness and economic distress in the family. My daughter was getting married in the month of November and we had high hopes on the horticultural production to support the marriage ceremony of my daughter but now we postponed the marriage till next November because of unavailability of money”. Mohd. Ayub of district Kulgam narrated, “Our house worth 20 lakh rupees got totally damaged due to the flood. We lived in a temporary tent for three months”. Manzoor Ahmad of Srinagar district narrated his horrific flood memories and stated, “The flood water came from all sides and our house was filled with water within ten minutes and we rushed to the third floor. We lived on the third floor of our house for 15 days with little food and water. The two storeys of our house were inundated for 15 days and we had to use the water motors to draw out the water from our house. We incurred a loss of 15 lakh rupees and it took us two years to cope-up with the economic loss”.

While recollecting the memories of recent floods in the Kashmir Valley, Abdul Samad of Srinagar said, “The recent floods of Kashmir Valley like the floods in 2014, 2015, 2017, 2019 and 2020 caused huge impact. The floods of 2015, 2017, 2019 and 2020 were not so much devastating as compared to the flood of 2014. We thought that we are all going to die and nothing will be left out there”.

Spatial dimension of relief

Which areas are vulnerable, and why the people who live there are vulnerable, is frequently part of a political discourse elicited by both international agencies and national governments in order to decide who should receive assistance and in what form. The politization of relief and rescue, as well as the power dynamics that underpin it (Bankoff et al. 2013), determines the distribution of relief.

Floods affect different sections of society differently. Vulnerability to floods depends upon the location of the settlement and the socio-economic conditions of the people. Thus, different classes are vulnerable to a different degree to floods. Floods expose the political setup of a region or a state. It shows the kind of political setup that governs the people and projects the political scenario of a region or a nation.

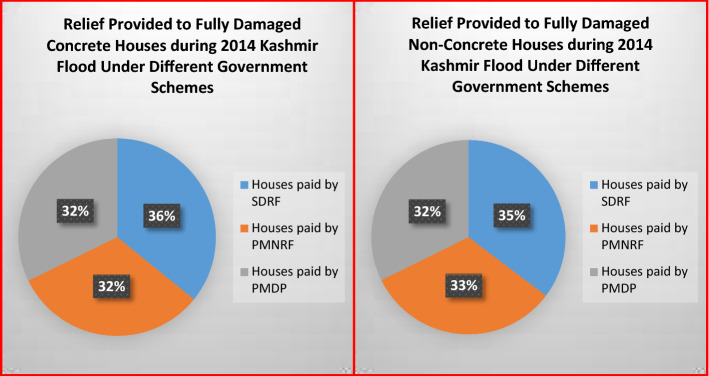

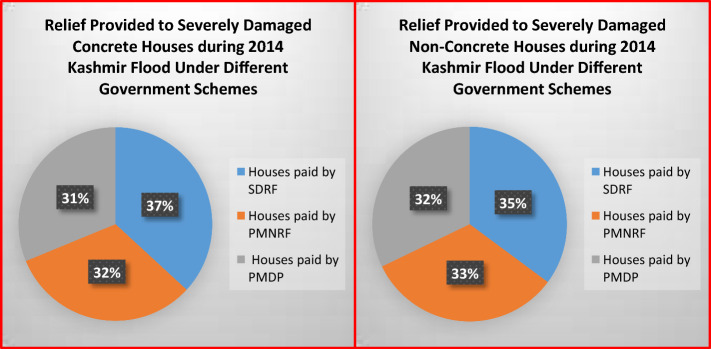

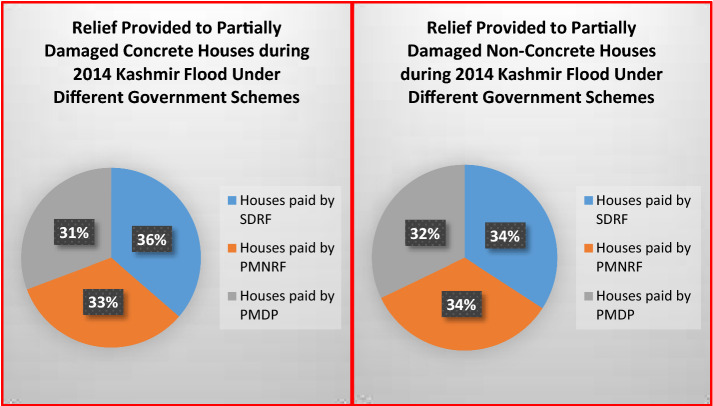

Tables 3, 4, and 5 and Figs. 5, 6 and 7 provide the spatial dimension of relief of the flood of 2014 in Kashmir Valley and show relief provided to total number of fully damaged houses under the government schemes like State Disaster Response Fund (SDRF), Prime Minister's National Relief Fund (PMNRF) and Prime Minister's Development Package (PMDP), relief provided to total number of severely damaged houses under SDRF, PMNRF and PMDP and relief provided to total number of partially damaged houses under SDRF, PMNRF and PMDP, respectively. These tables show that some people have been compensated for the loss incurred during the flood while as some people have not been compensated for their losses. The reports from field survey show that some people have been fairly compensated while as some people have been discriminated in terms of relief. It is also revealed that the relief was not uniformly distributed in the districts of the Valley, thus giving rise to the spatial dimension of the relief.

Table 3.

Relief provided to fully damaged houses during Kashmir’s 2014 flood under Prime Minister's Development Package (PMDP), Prime Minister's National Relief Fund (PMNRF) and State Disaster Response Fund (SDRF)

| District | Pucca (concrete) | Kacha (non-concrete) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total houses damaged | Houses paid by SDRF | Houses paid by PMNRF | Houses paid by PMDP | Total houses damaged | Houses paid by SDRF | Houses paid by PMNRF | Houses paid by PMDP | |

| Srinagar | 6048 | 5839 | 5537 | 5495 | 113 | 112 | 101 | 95 |

| Budgam | 875 | 861 | 714 | 857 | 26 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Anantnag | 1542 | 1534 | 1307 | 1304 | 272 | 270 | 246 | 246 |

| Baramulla | 190 | 190 | 190 | 190 | 149 | 149 | 149 | 149 |

| Kulgam | 231 | 231 | 231 | 226 | 108 | 108 | 108 | 105 |

| Shopian | 203 | 203 | 123 | 123 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 7 |

| Pulwama | 1957 | 1890 | 1565 | 1565 | 58 | 58 | 42 | 42 |

| Bandipora | 544 | 544 | 404 | 402 | 243 | 241 | 218 | 222 |

| Ganderbal | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Kupwara | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 11,593 | 11,295 | 10,074 | 10,165 | 982 | 975 | 897 | 892 |

Table 4.

Relief provided to severely damaged houses under SDRF, PMNRF & PMDP during Kashmir’s 2014 flood

| District | Pucca (concrete) | Kacha (non-concrete) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total houses damaged | Houses paid by SDRF | Houses paid by PMNRF | Houses paid by PMDP | Total houses damaged | Houses paid by SDRF | Houses paid by PMNRF | Houses paid by PMDP | |

| Srinagar | 25,426 | 24,759 | 20,359 | 19,588 | 78 | 62 | 58 | 54 |

| Budgam | 3538 | 3493 | 3304 | 3410 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Anantnag | 3923 | 3888 | 3672 | 3656 | 232 | 228 | 203 | 202 |

| Baramulla | 1288 | 1288 | 1288 | 1288 | 146 | 146 | 146 | 146 |

| Kulgam | 639 | 639 | 639 | 617 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 71 |

| Shopian | 181 | 181 | 181 | 181 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Pulwama | 1926 | 1612 | 1609 | 1609 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Bandipora | 1488 | 1487 | 1290 | 1288 | 71 | 71 | 57 | 59 |

| Ganderbal | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Kupwara | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 38,410 | 37,348 | 32,343 | 31,638 | 631 | 610 | 567 | 558 |

Table 5.

Relief provided to partially damaged houses under SDRF, PMNRF and PMDP during Kashmir’s 2014 flood

| District | Pucca (concrete) | Kacha (non-concrete) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total houses damaged | Houses paid by SDRF | Houses paid by PMNRF | Houses paid by PMDP | Total houses damaged | Houses paid by SDRF | Houses paid by PMNRF | Houses paid by PMDP | |

| Srinagar | 61,798 | 58,402 | 53,021 | 49,750 | 73 | 73 | 55 | 55 |

| Budgam | 12,485 | 9703 | 9462 | 6916 | 36 | 30 | 27 | 0 |

| Anantnag | 13,482 | 12,579 | 8246 | 8237 | 534 | 525 | 481 | 481 |

| Baramulla | 5969 | 5969 | 5969 | 5969 | 888 | 888 | 888 | 888 |

| Kulgam | 2111 | 2111 | 2111 | 2062 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 194 |

| Shopian | 911 | 911 | 911 | 911 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Pulwama | 11,203 | 9691 | 9536 | 9536 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Bandipora | 5039 | 4917 | 5110 | 4747 | 318 | 317 | 353 | 285 |

| Ganderbal | 328 | 328 | 328 | 328 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| Kupwara | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 113,413 | 104,698 | 94,781 | 88,543 | 2207 | 2191 | 2162 | 2061 |

Source: Divisional Commissioner’s Office, Srinagar

Fig. 5.

Relief provided to concrete and non-concrete fully damaged houses during 2014 Kashmir flood

Fig. 6.

Relief provided to concrete and non-concrete severely damaged houses during 2014 Kashmir flood

Fig. 7.

Relief provided to concrete and non-concrete partially damaged houses during 2014 Kashmir flood

The total number of fully damaged pucca houses (Concrete houses) by the 2014 flood in Kashmir Valley was 11,593, in which 11,295 houses were provided relief under SDRF, 10,074 houses were paid under PMNRF, and 10,165 were paid under PMDP. The total number of fully damaged kacha houses (non-concrete houses) is 982, in which 975 were provided relief under SDRF, 897 were paid under PMNRF, and 892 were paid under PMDP. A total of 38,410 pucca and 631 kacha houses were severely damaged, in which 37,348 pucca houses and 610 kacha houses were provided relief under SDRF. A total of 113,413 pucca and 2207 kacha houses were partially damaged, in which 104,698 pucca houses and 2191 kacha houses were provided relief under SDRF.

Politics of rescue and relief

Disasters serve as flashpoints for political and social revelations. Pelling and Dill (2006) say, “The way in which the state and other sectors act in response and recovery is largely predicated on the kind of political relationships that existed between sectors before the crisis”. Despite the disruption and chaos that tend to occur in the immediate aftermath of catastrophes, anti-social forms of behaviour, panic, and apathy are uncommon reactions. Individual actions are likely to be rational and socially oriented, although potentially uncoordinated. People who end up as leaders in disaster usually have a well-defined role, which they play with the benefit of prior experience, appropriate skills, and a certain sense of detachment from the proceedings (Fritz 1957). Politicians and civil servants spin their own tales, explaining the links between vulnerability, hazards, and disaster. These narratives reflect political interests and motivations, but they are also influenced by cultural patterns of governance, such as risk governance (Bankoff et al. 2013). Responses to risk and disaster have an impact on state–society relations (Bankoff 1999).

Floods are the moments of social and political rupture. They give an opportunity for deep rooted political narratives that have transcended over the years. The 2014 flood in Kashmir Valley was the most devastating flood in the Valley's living memory, affecting nearly everyone. The relief and rescue operations witnessed a strange scenario during the deluge which created wide animosity among the people towards the administration. There is an increasing concern of the politicization of the disaster relief as the most vulnerable people often receive less relief.

Disasters act as moments of political and social exposure. It was clearly evident during the 2014 flood in Kashmir. The abrupt suspension of normal life in Kashmir due to the flood lifted the veil of projected political normalcy in the Valley. It showed the broken and distrusted relationship between the people of Kashmir and the state. The rise of volunteerism of the community members and dysfunctionality of the state exposed the inability of the administration to deal with the flood. The flood in Kashmir revealed the political rupture in the valley to a great extent and showed how deep this rupture is. The political stakes during the flood were high. The ethnographic work on the 2014 flood in Kashmir discusses the spatial dimension of relief and rescue operations and highlights the role played by the people and the government during and after the flood as ethnography provides the grassroots level information of the narratives and issues during the disasters.

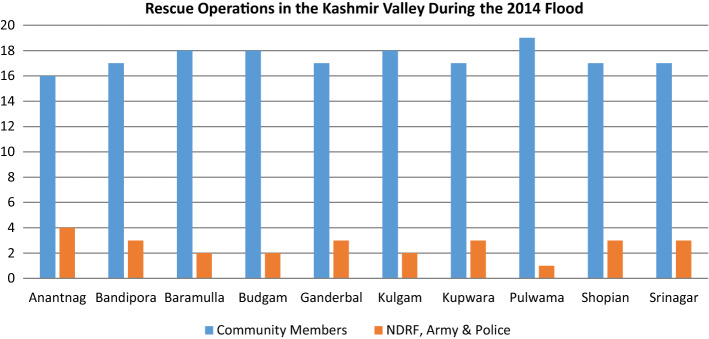

The rescue during the 2014 Kashmir flood was done mostly by the community members and volunteers. 74% of rescue was done by the community members of Kashmir while 26% rescue was done by army, police, and NDRF. These figures show that it was the community members especially youth who emerged as the heroes during rescue operations (Table 6 and Fig. 8).

Table 6.

Rescue during 2014 Kashmir flood

| Rescue operation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| District | Houses surveyed | Rescue | |

| Community members | NDRF, army and police | ||

| Anantnag | 20 | 16 | 4 |

| Bandipora | 20 | 17 | 3 |

| Baramulla | 20 | 18 | 2 |

| Budgam | 20 | 18 | 2 |

| Ganderbal | 20 | 17 | 3 |

| Kulgam | 20 | 18 | 2 |

| Kupwara | 20 | 17 | 3 |

| Pulwama | 20 | 19 | 1 |

| Shopian | 20 | 17 | 3 |

| Srinagar | 20 | 17 | 3 |

| Total | 200 | 74 | 26 |

Source: Primary survey

Fig. 8.

Rescue operations in the Kashmir Valley during the 2014 flood

Nazir Ahmad of Srinagar narrated the rescue scenario during the flood and said, “We were rescued by the youth of Kashmir who brought boats with them for our rescue. We were stuck in second storey of our house with no food and drinking water. But the youth came and rescued us and took us to Dalgate relief camp. We resided there for 15 days”. Bashir Ahmad of Anantnag, while recollecting the horrific memories of the flood, narrated, “If the local youth had not come for our rescue, we would have died”. A volunteer from Srinagar narrated, “Relief and rescue operations during the flood had their own priorities. The administration rescued the tourists first, then politicians and the elite class, the migrant labourers and lastly the local people”. This created the animosity among the local population towards the administration.

The distribution of relief by the administration had its own priorities. According to several respondents, the upper class people and the political elite were provided more relief as compared to the lower class people. There was bias from the authorities in the distribution of relief as the politically influential people were provided more relief as compared to the damage they incurred. Mushtaq Ahmad from Baramulla, while narrating the bias from the authorities in distributing relief, said, “The politically influential people in my village were provided a lot of relief. We incurred a loss of 8 lakh rupees but were provided the relief of merely 2 lakh rupees while as some people who incurred the loss of 2 lakh rupees were provided the relief of 4 lakh rupees”. Some of the relief was provided by some NGOs like GOONJ and local religious organizations.

The total absence of civilian government was an important aspect of flood risk management. The inability of the government to control the damage of the flood was evident by the lack of proper disaster management facilities. In 2014, Muzamil Jaleel, a journalist with The Indian Express narrated the situation as “The rescue operation isn't led by anyone because there isn't any communication between officials. The people have no means to contact anybody in the government. The Army, Air Force and NDRF are functioning on their own. The cell phones of almost all government officials are defunct. Director of Health Services (Kashmir) Saleem-ur Rahman, for example, said he could not contact his officials. The only network functional is Aircel; government officials use BSNL or Airtel. All government offices are shut, as are the civil secretariat and the high court. The state police's control room is being run from a DIG's car where a few officers use wireless to communicate among themselves. On Tuesday night, police managed to send a few radio updates to the public”. The then Chief Minister of J&K, Omar Abdullah, while acknowledging the complete breakdown of his administration in an interview on 11th September 2014, said, “I had no government for the first 36 h. My secretariat, the police headquarters, the control room, fire services, hospitals, all the infrastructure was underwater. I had no cell phone and no connectivity. I am now starting to track down ministers and officers. Today I met ministers who were swept up by the floods”. According to news reports, during the first critical days after the floods hit Srinagar, the Chief Minister was working with only two of his senior functionaries, Chief Secretary Iqbal Khanday and Director General of Police K Rajendra (Arshad 2014). As per Rapid Assessment Report (2014), which surveyed 26 relief camps across the city, “a total of 26 relief shelters in highly affected parts of Srinagar housed 37,450 people. Out of the 26 relief shelters studied, 7.7% received food supplies from NGOs while 92.3% of the relief shelters received food supplies from community donations. Around 200 pregnant women were reported to be present in these shelters”.

Rescue and relief, it emerged, had its own agenda. In Kashmir, the locals were initially largely left to fend for themselves, while 13,000 tourists and pilgrims were flown out, followed by officials, and others with the right contacts. A large number of migrant labourers remained stuck with the community members. There may have been reasons for this, no doubt—to ease the burden of rehabilitation and care, and the usual antipathy to working-class people. This meant that rescuing local people and poor migrants was delayed. On the 10th day of the floods (14 September 2014), the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the 15th Corps, Lt General Subarat Saha, made the claim that Srinagar had “well transitioned” from rescue to relief work and said, “Nobody is marooned any longer, strictly speaking”. The director general of the National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) announced three days later, on 17 September 2014 that in “technical terms rescue operations (have) concluded”. On the 10th day, the army claimed that it had rescued 1, 84,000 people across Kashmir, using 224 of their boats and 148 of the NDRF. But, the same day, Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, while criticizing “rumour mongers”, said that 80,000 people had been rescued, of whom 59,000 had been assisted by the army, 10,000 by the NDRF, and 21,000 by the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), the police, and local volunteers. But by far the biggest and most heroic role was that of the community members. Given the scale of the devastation, 30,000 troops (9000 in Jammu and 21,000 in Kashmir) were too few to rescue the 400,000 to 500,000 marooned in Srinagar alone, not to speak of Kulgam, Pulwama, and Budgam (Navlakha 2014).

The narratives that emerged during the 2014 flood were regarding the politics of relief and rescue, unfair treatment to different sections of the society, rising political rupture and apathy of the administration to effectively deal with the floods. The people who had influence in the political set up received better relief as compared to the people who did not have any influence in the political sphere. In terms of rescue operations, the tourists and the bureaucrats were given the preference and the community members were left to save themselves. This widened the distrust between the government and the community members to the extent that several protests were seen against the administration about the handling of the relief and rescue actions. The most important narrative that emerged during the flood was the communitarianism of the community members, and it was them who saved themselves and several tourists and took them to safer places.

Communitarianism

Power is sometimes associated with "local knowledge", i.e. practice that arose out of necessity and is based on first-hand experience. It could take the form of first-hand knowledge of the environment and its dangers and limitations, which could provide a practical guide to what steps should or should not be taken in the face of a sudden or slow-onset hazard. It may also stem from a memory pool, whether traditional or invented, that has been added to and mutated over generations, and it is frequently manifested at the community level in the form of self-help practises and mutual assistance associations (Bankoff et al. 2013). People are social actors who can process social experience and respond accordingly, rather than simply reacting to what happens around them (Long 1992).

Floods have always been a part of the Kashmir Valley's history, and people who live in flood-prone areas have developed various flood-resilience measures based on their own experiences and knowledge, and these strategies have become ingrained in Kashmiri culture over generations. When floods occurred, like the 2014 flood, people have always been prepared to deal with them and have not relied heavily on administration or any other source for assistance. The relief and rescue operations by the community members of Kashmir during recent floods, especially during the 2014 flood, gave rise to a strong feeling of communitarianism and conscious society. The local knowledge of the people was the key in understanding the flood situation. The people helped the needy without any discrimination of religion, caste or race. During the flood, various religious and social organizations distributed food items, blankets, vegetables, drinking water bottles, and other essential items for the survival of the people. They also provided medicines to pregnant women, lactating mothers, and patients. In different parts of the valley, several local committees were formed in villages and towns to distribute the essential items to the people in need. Rescue operations were mostly done by the community members, and the boatmen provided their boats for the rescue operations. The people were left to themselves during the flood, and it was up to them to save themselves and rise to the occasion, which resulted in the strong feelings of communitarianism and strengthened the social fabric. The people from villages collected the essential items like food packets, medicines, drinking water bottles, cereals, blankets, and rice and distributed it to the people of the towns of Srinagar City and Anantnag. Several local self-help groups were created in the districts of Anantnag, Baramulla, Bandipora, and Srinagar who distributed the essential services including the monetary help to the affected people of these districts and thus strengthened the social fabric.

The people of Kashmir have always helped each other at the time of need. Whether it was the recent floods or the COVID-19 pandemic, they have come together as a community to help the distressed population, and for the disaster response to be effective, the affected communities should have the voice to recognize their risk and their active role in devising strategies to deal with the disasters.

Conclusion

The spatial dimension of the 2014 flood in Kashmir Valley depicts the struggle of the valley to survive. The damage to infrastructure and settlements greatly hampered the socio-economic development. The floods led to the political crisis in the Valley, and the spatial dimension shows that the people of the Kashmir Valley were not fairly compensated for their loss and there was partiality in rescue and relief operations. The economically well-off people were rescued first and also compensated fairly as compared to economically poor people, thus reflecting the class inequality. The rescue operations were highly biased. The distressed population took almost two years to reconstruct their houses. The floods had a long-term impact on the memory and economic and social conditions of the people. The community members emerged as heroes during the cataclysm and showed strong feeling of communitarianism. The study's relevance resides in its policy implications for flood management in the global South, in the sense that strong communitarianism and the application of local knowledge are crucial components of flood management in the global South.

Acknowledgements

I am highly thankful to the Editors of the Natural Hazards journal for carefully handling the manuscript and providing useful suggestions. I am also thankful to the anonymous reviewers for providing important suggestions to improve the quality of the paper.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that no conflict of interest is involved in the paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adhikari P, Hong Y, Douglas KR, Kirschbaum DB, Gourley J, Adler R, Brakenridge GR. A digitized global flood inventory (1998–2008): compilation and preliminary results. Nat Hazards. 2010;55(2):405–422. doi: 10.1007/s11069-010-9537-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar Alam M, Bhat S, Farooq H, Ahmad B, Ahmad S, Sheikh AH. Flood risk assessment of Srinagar city in Jammu and Kashmir, India. Int J Disaster Resil Built Environ. 2018;9(2):114–129. doi: 10.1108/IJDRBE-02-2017-0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alam A, Bhat MS, Kotlia BS, Ahmad B, Taloor AS, AK, Ahmad HF, Coexistent pre-existing extensional and subsequent compressional tectonic deformation in the Kashmir basin, NW Himalaya. Quat Int. 2017;444:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander D. Natural disasters. London: Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad S (2014) J&K floods: over 200 dead, 47,000 people rescued. https://reliefweb.int/report/india/jk-floods-over-200-dead-47000-people-rescued

- Bankoff G. A history of poverty: the politics of natural disasters in the Philippines, 1985–95. Pac Rev. 1999;12(3):381–420. doi: 10.1080/09512749908719297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bankoff G, Frerks G, Hilhorst D, editors. Mapping vulnerability: disasters, development and people. London: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat MI. Thermal and tectonic evolution of Kashmir basin visà-vis petroleum prospects. Tectonophysics. 1982;88:117–132. doi: 10.1016/0040-1951(82)90205-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt CM, Rao GS, Farooq M, Manjusree P, Shukla A, Sharma SVSP, Dadhwal VK. Satellite-based assessment of the catastrophic Jhelum floods of September 2014, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Geomatics Nat Hazards Risk. 2017;8(2):309–327. doi: 10.1080/19475705.2016.1218943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Madge N. Despite the welfare state: a report on the SSRC/DHSS programme of research into transmitted deprivation. Portsmouth: Heinemann Educational Publishers; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Burbank DW. The chronology of intermontane-basin development in the northwest Himalaya and the evolution of the Northwest Syntaxis. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1983;64:77–92. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(83)90054-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter O, Platt S, Mahdavian F (2020) Disaster recovery case studies: India Pakistan floods 2014. Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies at the University of Cambridge Judge Business School

- Census of India, 2011

- CRED (2019) CRED: EM-DAT: the international disasters database. https://www.emdat.be/database

- Dhar ON, Nandargi S. Hydrometeorological aspects of floods in India. Nat Hazards. 2003;28(1):1–33. doi: 10.1023/A:1021199714487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz CE. Disasters compared in six American communities. Hum Organ. 1957;16(2):6–9. doi: 10.17730/humo.16.2.r30357044021352n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Annual Global climate and catastrophe report 2014: impact forecasting (2015) Aon Benfield. http://thoughtleadership.aonbenfield.com/Documents/20150113_ab_if_annual_climate_catastrophe_report.pdf

- Gulzar SM, Mir FUH, Rafiqui M, Tantray MA. Damage assessment of residential constructions in post-flood scenarios: a case of 2014 Kashmir floods. Environ Dev Sustain. 2021;23:4201–4214. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00766-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert D. Urban deprivation: definition, measurement and spatial qualities. Geogr J. 1975;141(3):362–372. doi: 10.2307/1796471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilhorst D (2013) Complexity and diversity: unlocking social domains of disaster response. In: Mapping vulnerability. Routledge, London, pp 71–85

- Iqbal F (2019) The dying Wullar. https://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/opinion/the-dying-wullar-2/. Greater Kashmir, 27 June, 2019.

- Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society . Occupational hazard, The Jammu and Kashmir Floods of September 2014. Srinagar: Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman SN. Global perspectives on loss of human life caused by floods. Nat Hazards. 2005;34(2):151–175. doi: 10.1007/s11069-004-8891-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Acharya P. Flood hazard and risk assessment of 2014 foods in Kashmir Valley: a space-based multisensor approach. Nat Hazards. 2016;84(1):437–464. doi: 10.1007/s11069-016-2428-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JYS, Russell BD, Connell SD (2019) Summary for policymakers. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_SPM_version_report_LR.pdf.

- Long N (1992) Introduction: from paradigm lost to paradigm regained? The case for an actor-oriented sociology of development; Conclusion. Battlefields of knowledge. The interlocking of theory and practice in social research and development. Routledge, London, pp 3–15

- Malik IH. Socio-economic, political and ecological aspects of ecotourism in Kashmir. Best Int J Hum Arts Med Sci (BEST: IJHAMS) 2015;3(11):155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Malik IH, Hashmi SNI. Ethnographic account of flooding in North-Western Himalayas: a study of Kashmir Valley. GeoJournal. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10708-020-10304-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik IH, Hashmi SNI. The great flood and its aftermath in Kashmir Valley: impact, consequences and vulnerability assessment. J Geol Soc India. 2021;97(6):661–669. doi: 10.1007/s12594-021-1742-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meraj G, Romshoo SA, Yousuf AR, Altaf S, Altaf F. Assessing the influence of watershed characteristics on the flood vulnerability of Jhelum basin in Kashmir Himalaya: reply to comment by Shah 2015. Nat Hazards. 2015;78(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11069-015-1861-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra AK. A study on the occurrence of flood events over Jammu and Kashmir during September 2014 using satellite remote sensing. Nat Hazards. 2015;78:1463–1467. doi: 10.1007/s11069-015-1768-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed AAA, Naqvi HR, Firdouse Z. An assessment and identification of avalanche hazard sites in Uri sector and its surroundings on Himalayan mountain. J Mt Sci. 2015;12(6):1499–1510. doi: 10.1007/s11629-014-3274-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Navlakha G. Kashmir deluge: natural disaster made worse. Econ Polit Wkl. 2014;49:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Norris G. Defining urban deprivation. In: Jones C, editor. Urban deprivation and the inner city. London: Croom Helm; 1979. pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pelling M, Dill K. ‘Natural disasters’ as catalysts of political action (ISP/NSC Briefing Paper 06/01) London: Chatham House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rapid Assessment Report (2014) Rapid needs assessment report: J&K Floods 2014. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/JRNA%20Report%20Odisha%20Flood_26Aug2014_IAG%20Odisha.pdf

- Ray K, Bhan S, Bandopadhyay B. The catastrophe over Jammu and Kashmir in September 2014: A meteorological observational analysis. Curr Sci. 2015;109(3):580–591. [Google Scholar]

- Romshoo SA, Altaf S, Rashid I, Dar RA. Climatic, geomorphic and anthropogenic drivers of the 2014 extreme flooding in the Jhelum basin of Kashmir, India. Geomatics Nat Hazards Risk. 2018;9(1):224–248. doi: 10.1080/19475705.2017.1417332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saharia M, Jain A, Baishya RR, Haobam S, Sreejith OP, Pai DS, RafieeiNasab A. India flood inventory: creation of a multi-source national geospatial database to facilitate comprehensive flood research. Nat Hazards. 2021;108:619–633. doi: 10.1007/s11069-021-04698-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal R, Yasir S. The politics of natural disasters in protracted conflict: the 2014 flood in Kashmir. Oxf Dev Stud. 2017;45(4):424–442. doi: 10.1080/13600818.2016.1276160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm B, Ballesteros Cánovas JA, Macdonald N, Toonen WH, Baker V, Barriendos M, Wetter O. Interpreting historical, botanical, and geological evidence to aid preparations for future floods. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Water. 2019;6(1):e1318. doi: 10.1002/wat2.1318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yaseem F (2014) Kashmir floods an international disaster: Govt. Rising Kashmir

- Zarekarizi M, Srikrishnan V, Keller K. Neglecting uncertainties biases house-elevation decisions to manage riverine flood risks. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]