Abstract

Background

Libman-Sacks endocarditis (LSE) is a rare cardiovascular manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus/antiphospholipid syndrome that is described as a sterile verrucous nonbacterial vegetative lesion. These lesions can cause progressive damage to the heart valves leading to valve surgery. The most common valves to be affected are the aortic and mitral valves. Libman-Sacks endocarditis is associated with malignancies, other systemic diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS). The majority of LSE patients are usually asymptomatic. Case Summary. We describe a 39-year-old male patient who presented with increasing shortness of breath and pulmonary congestion. He was found to have severe mitral valve regurgitation and mitral stenosis. Transesophageal echocardiogram confirmed the diagnosis of Libman-Sacks endocarditis with thickened mitral valve leaflets with symmetrical mass-like structure causing a restriction in the valve function during both cardiac phases later diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus by immunology. The patient was started on diuretics, anticoagulants, angiotensin inhibitors, beta-blockers, and hydroxychloroquine. He underwent successful mechanical mitral valve replacement with a 27 mm St. Jude valve. The mitral valve was found to be grossly thickened with friable tissue and complete amalgamation of the leaflets with subvalvular apparatus. The patient suffered some warfarin adverse effects a year later but did well otherwise.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates that Libman-Sacks endocarditis can be the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. Early and prompt diagnosis of LSE can prevent and lessen the many side effects associated with thromboembolism. Additionally, addressing the underlying disease is key to successful treatment.

1. Introduction

Libman-Sacks endocarditis (LSE) is noninfectious endocarditis that is sometimes referred to as nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE), marantic endocarditis, or verrucous endocarditis. It is characterized by deposition of thrombi mainly on aortic and mitral valves; involvement of other valves is less common. It was first described by Emanuel Libman and Benjamin Sacks in 1924 [1]. LSE was mostly associated with malignancies, for example, patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma were found to have a higher risk of developing LSE with systemic embolization being the leading cause of morbidity [2]. Additionally, LSE is linked to other systemic diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS). LSE is encountered among 10% of patients with SLE; it correlates with the disease activity, duration, anticardiolipin antibodies, and APS manifestations. SLE patients with LSE frequently have evidence of valvular affection and lesion progression as shown by Moyssakis et al. [1].

The majority of LSE patients are usually asymptomatic, while if the patient was symptomatic it is usually due to embolic infarctions either as cerebrovascular or systemic thromboembolism. SLE and APS patients may present with signs and symptoms of their underlying diseases, such as malar rash and recurrent miscarriages.

The prognosis of LSE has not been well defined; it is usually considered poor, especially if those patients develop recurrent thromboembolism [3].

We are describing an adult patient who presented with LSE as the first manifestation of SLE.

2. Case Presentation

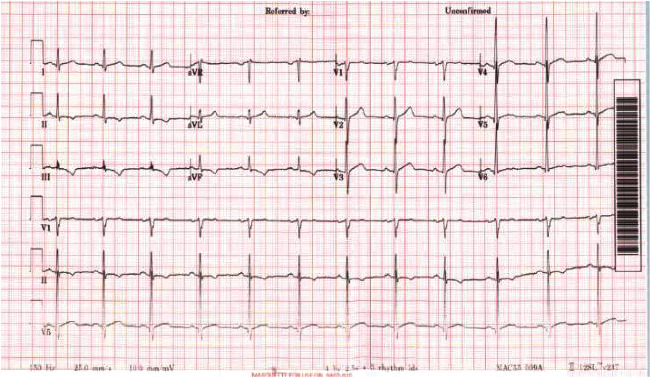

A 39-year-old male, who was medically free prior to this, presented complaining of a three-month history of exertional dyspnea classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III, associated with cough and palpitation. The patient suffered from five ill-defined syncopal attacks during the past year. He reported a three-month history of lethargy, loss of appetite, and weight loss. The patient denied any personal history of fever, joint pain, or drug abuse. Family history was unremarkable for malignancies or cardiac conditions. Upon admission, the patient was vitally stable with normal saturation on ambient air. Chest examination revealed decreased breath sounds in the right lower zone with bilateral basal crackles, soft first heart sound, normal second heart sound, loud pansystolic murmur, and a soft diastolic rumble at the mitral area. His initial blood work is shown in Table 1. ECG revealed T-wave inversion in leads II, III, and AVF (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Initial laboratory data for the patient at presentation.

| Labs | Results | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| White blood count | 5.5 × 109/L | 4.0–11.0 × 109/L |

| Hemoglobin | 11.9 g/dL | 11.5–16.5 g/dL |

| Platelet | 111 × 109/L | 150–450 × 109/L |

| Neutrophil count | 3.14 × 109/L | 2–7.5 × 109/L |

| Lymphocyte count | 1.08 × 109/L | 1.5–4 × 109/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 8.1 mmol/L | 2.1–7.1 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 150 μmol/L | 62–106 μmol/L |

| Brain natriuretic peptide | 1585 pg/mL | <100 pg/mL |

| High-sensitivity troponin | >0.03 ng/mL | >0.03 ng/mL |

Figure 1.

Patient's electrocardiogram showing inverted T-wave in leads II, III, and AVF.

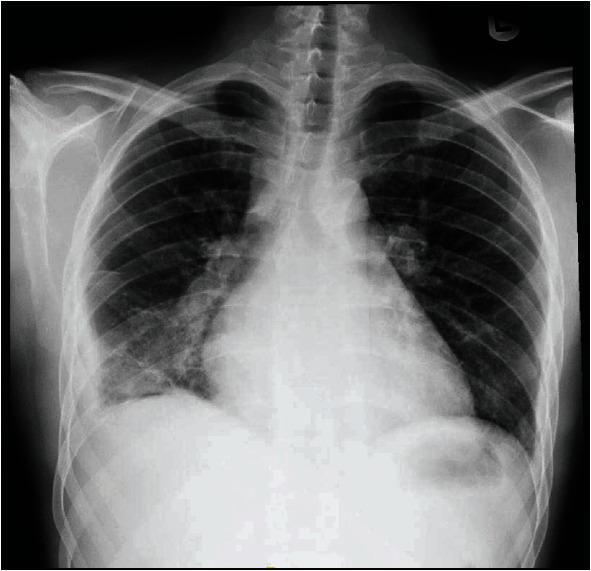

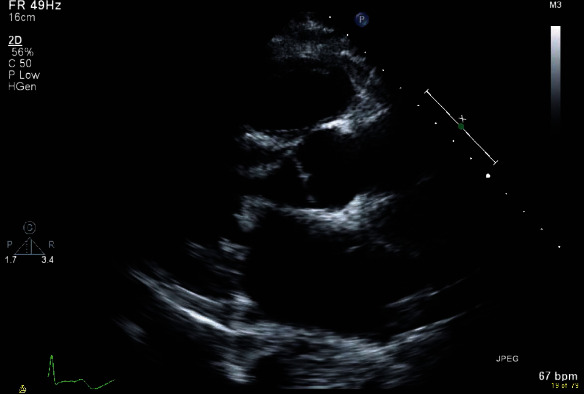

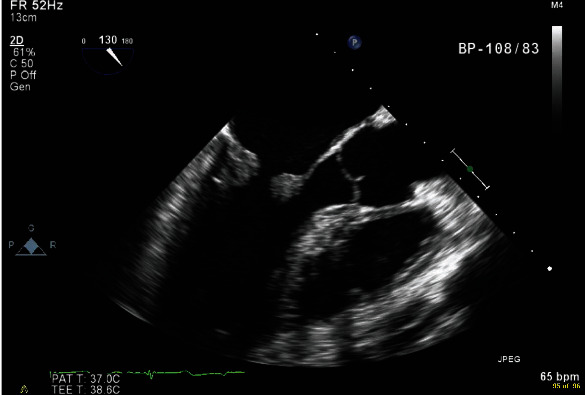

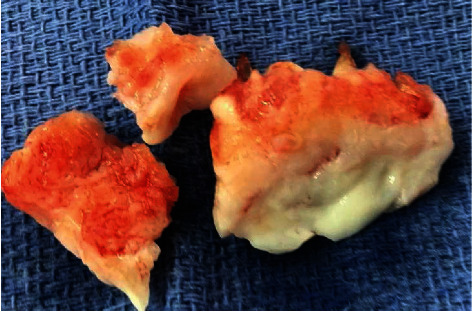

Chest imaging revealed cardiomegaly and right pleural effusion with right lower lobe consolidations (Figure 2). Echocardiogram showed a dilated right ventricle with mild to moderate tricuspid regurgitation and severe rheumatic mitral stenosis with moderate to severe mitral regurgitation (Figure 3). The patient was then commenced on diuretics, anticoagulants, angiotensin inhibitors, and beta-blockers. Transesophageal echocardiogram showed thickened mitral valve leaflets with symmetrical mass-like structure on the ventricular surface involving the tips of both leaflets extending to the body, causing a restriction in the valve function during both cardiac phases (Figure 4). Later, the patient underwent a diagnostic angiography, which showed normal coronary arteries. The immunology test came back confirming the diagnosis of SLE (Table 2). Following cardiac team discussion, the patient underwent mitral valve replacement surgery. During the operation, the mitral valve was found to be grossly thickened with friable tissue and complete amalgamation of the leaflets with subvalvular apparatus (Figure 5). The valve was replaced with a 27 mm St. Jude valve. Postop echocardiogram was performed; thus, the surgery was deemed successful and his hospital stay was uneventful. Tissue biopsy showed degenerative changes, myxoid areas with hemorrhage admixed with acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. In addition, fibroid necrosis was present without calcification. The diagnosis of LSE was confirmed with SLE as underlying disease. The patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 400 mg daily, warfarin, and aspirin. At one-year follow-up, he had an increased intraocular pressure, hyphema, total vitreous hemorrhage, and choroidal hemorrhage. The patient was admitted and underwent hyphema drainage and trabeculectomy. Otherwise, the patient was doing well.

Figure 2.

Patient's chest X-ray demonstrating cardiomegaly and right lower lobe consolidations with pleural effusion.

Figure 3.

Parasternal long axis view revealing a diffused leaflet thickening of the mitral valve.

Figure 4.

Transesophageal echocardiogram showing a symmetrical mass-like structure on the ventricular surface involving the tips of both leaflets extending to the body, causing a restriction in the valve function.

Table 2.

Autoimmune laboratory tests concerning the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus.

| Labs | Results | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Antinuclear antibody | Positive | Negative |

| Anti-double-stranded DNA | 355.7 | <68.6 is negative 68.6–229 is moderately positive >229 is strongly positive |

| Ribonucleoprotein antibody | 472.5 | <20 is negative 20–39 is weakly positive 40–80 is moderately positive >80 is strongly positive |

| Anti-Smith antibody | 114.71 | <20 is negative 20–39 is weakly positive 40–80 is moderately positive >80 is strongly positive |

| C3 complement | 0.8 g/dL | 0.9–1.9 g/dL |

| C4 complement | >0.06 | 0.1–0.4 g/dL |

Figure 5.

Gross anatomy of the mitral valve leaflets in keeping with Libman-Sacks endocarditis.

3. Discussion

Cardiac involvement in SLE is common. It is estimated that more than 50% of SLE/APS patients have cardiovascular manifestations in the form of pericarditis, myocarditis, LSE, pulmonary arterial hypertension, conduction disease, and coronary artery disease. Left-sided heart valves are by far the most affected. It has previously been reported to have cardiac involvement as the main reason for presentation; however, this is extremely rare [1–8].

Multivalvular involvement often occurs, but typically, the most frequently affected valve is the mitral valve with the vegetations occurring near the edge of the valve or on both of its surfaces. Involvement of the atrial or ventricular endocardium or the chordae tendineae and papillary muscles is rare.

The approach to diagnose LSE might not be simple as some SLE or APS patients are asymptomatic. Echocardiography is the best first modality to diagnose LSE, but transesophageal echocardiography is more sensitive and specific than transthoracic echocardiography [9, 10]. Doppler echocardiography detects between 18% and 50% of valve diseases [1–10], while transesophageal echocardiography detects up to 74% [9, 10]. LSE on imaging is described as irregular heterogeneous echo density with the absence of independent motion of the verrucous vegetations on the cardiac valves and endocardium [9, 10]. The mitral and aortic valves are most affected by leaflet thickening and regurgitation. Although the origin of valvular lesions in SLE is closely linked to the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies [10], negative test results have been described in literature in other patients with SLE and LSE [8] or even in nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis without underlying disease.

The LSE diagnosis is difficult to be confirmed by laboratory tests; however, patients who are suspected of having LSE must have complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic workup, blood cultures, autoimmune profile, and hypercoagulable workup [1–9].

When treating LSE, the underlying disease, either SLE or APS, must be addressed. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), an antimalarial drug, has been an effective option for managing SLE, especially in the early stages [1–10]. Its effectiveness has been established in the mild form of SLE, while not as effective in preventing severe SLE manifestations such as glomerulonephritis and central nervous system involvement [11].

Corticosteroids are considered a treatment option to reduce the inflammatory reaction caused by LSE; however, they can lead to tissue scarring and fibrosis, predisposing to further valvular damage [11, 12]. Anticoagulation should be considered in SLE/APS patients as secondary prevention for thromboembolic events, especially those who have had previous thromboembolic events [11–15].

Surgical valve replacement is recommended for symptomatic and severe cases of LSE. Mechanical valve replacement in females of reproductive age is not preferable as they would require to be put on an anticoagulation regime with increased fetal and maternal side effects. Nonetheless, it is still recommended as many authors believe that SLE/APS patients will eventually end up on anticoagulants for the disease-associated thromboembolism [14, 15].

4. Conclusion

LSE is rare as the first manifestation of SLE/APS. We presented a 39-year-old male with LSE as the initial manifestation of SLE. It was successfully diagnosed by echocardiography and treated with mitral valve replacement surgery. The case highlights SLE as a differential diagnosis when encountering a healthy individual with new-onset valve disease. Early and prompt diagnosis of LSE can prevent and lessen the many side effects associated with thromboembolism.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Moyssakis I., Tektonidou M. G., Vasilliou V. A., Samarkos M., Votteas V., Moutsopoulos H. M. Libman-Sacks endocarditis in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence, associations, and evolution. The American Journal of Medicine. 2007;120(7):636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.González Quintela A., Candela M. J., Vidal C., Román J., Aramburo P. Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis in cancer patients. Acta Cardiologica. 1991;46(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roldan C. A., Sibbitt W. L., Qualls C. R., et al. Libman-Sacks endocarditis and embolic cerebrovascular disease. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2013;6(9):973–983. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty N. E., Siegel R. J. Cardiovascular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. American Heart Journal. 1985;110(6):1257–1265. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foroughi M., Hekmat M., Ghorbani M., Ghaderi H., Majidi M., Beheshti M. Mitral valve surgery in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. The Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014:9. doi: 10.1155/2014/216291.216291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Godoy M. F., de Oliveira C. M., Fabri V. A., et al. Long-term cardiac changes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. BMC Research Notes. 2013;6(1) doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma J., Lasic Z., Bornstein A., Cooper R., Chen J. Libman-Sacks endocarditis as the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent, with a review of the literature. Cardiology in the Young. 2013;23(1):1–6. doi: 10.1017/S1047951112001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen S., Smith B., Ilina M., Bowen C., Martin N. PReS-FINAL-2307: Libman-Sacks endocarditis as a presentation for systemic lupus erythematous in an adolescent with isolated mitrial regurgitation and Noonan syndrome. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2013;11(Supplement 2) doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-11-s2-p297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gouya H., Cabanes L., Mouthon L., Pavie A., Legmann P., Vignaux O. Severe mitral stenosis as the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus in a 20-year-old woman: the value of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of Libman-Sacks endocarditis. The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2014;30(5):959–960. doi: 10.1007/s10554-014-0418-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roldan C. A., Shively B. K., Lau C. C., Gurule F. T., Smith E. A., Crawford M. H. Systemic lupus erythematosus valve disease by transesophageal echocardiography and the role of antiphospholipid antibodies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1992;20(5):1127–1134. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90368-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dandekar U. P., Watkin R., Chandra N., et al. Aortic valve replacement for Libman-Sacks endocarditis. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2009;88(2):669–671. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akhlaq A., Ali T. A., Fatimi S. H. Mitral valve replacement in systemic lupus erythematosus associated Libman- Sacks endocarditis. Journal of the Saudi Heart Association. 2016;28(2):124–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibrahim A. M., Siddique M. S. Stat Pearls. Treasure Island FL: Stat Pearls Publishing; 2020. Libman Sacks endocarditis. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doria A., Zen M., Canova M., et al. SLE diagnosis and treatment: when early is early. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2010;10(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hojnik M., George J., Ziporen L., Shoenfeld Y. Heart valve involvement (Libman-Sacks endocarditis) in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Circulation. 1996;93(8):1579–1587. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.8.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.