Abstract

The fruits of leguminous plants Cercis Chinensis Bunge are still overlooked although they have been reported to be antioxidative because of the limited information on the phytochemicals of C. chinensis fruits. A simple, rapid and sensitive HPLC-MS/MS method was developed for the identification and quantitation of the major bioactive components in C. chinensis fruits. Eighteen polyphenols were identified, which are first reported in C. chinensis fruits. Moreover, ten components were simultaneously quantified. The validated quantitative method was proved to be sensitive, reproducible and accurate. Then, it was applied to analyze batches of C. chinensis fruits from different phytomorph and areas. The principal components analysis (PCA) realized visualization and reduction of data set dimension while the hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) indicated that the content of phenolic acids or all ten components might be used to differentiate C. chinensis fruits of different phytomorph.

Keywords: C. chinensis fruits, HPLC-MS/MS, Polyphenols, Principal components analysis, Hierarchical cluster analysis

Graphical abstract

Eighteen polyphenols were quickly identified, and they were the first reported in C. chinensis fruits. The mass fragmentation pattern was summarized in this paper. A developed HPLC-MS/MS method to simultaneously quantify ten polyphenols was used for the determination of polyphenols in batches of C. chinensis fruits from different phytomorph and areas. The results of PCA and HCA realized visualization and reduction of data set dimension and provided the theoretical reference for the quality evaluation of C. chinensis fruits.

Highlights

-

•

Eighteen polyphenols were quickly identified, and they were the first reported in C. chinensis fruits.

-

•

Mass fragmentation pattern of identified 18 polyphenols were elucidated.

-

•

Simultaneously quantify 10 polyphenols in C. chinensis fruits by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS.

-

•

PCA and HCA realized visualization for quality evaluation of C. chinensis fruits.

1. Introduction

Cercis Chinensis Bunge (C. chinensis), well-known as an ornamental plant widely distributed in Southeast China, actually has multiple bioactivities. The bark and wood of C. chinensis have been used to activate blood as well as subdue swelling and detoxicating. Its flowers can treat rheumatic pain and its leaves have good analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects [1]. Based on the above bioactivities, different parts of C. chinensis, especially flowers, are used as additives in food or ingredients in health products. They are widely used for extraction of natural edible red pigment because many studies have shown that C. chinensis flowers contain anthocyanins [2].

Additionally, C. chinensis fruits can treat coughs, and it was reported to be ingredients of some health products like healthcare flour. However, few studies on the phytochemicals of the fruits have been reported in past years. Chen et al. [3] optimized the extraction of total flavonoids in C. chinensis fruits and studied the scavenging effect on hydroxyl radicals. It has been reported that flavonoids are correlated with the mitigation of the risks of various diseases, such as influenza virus [4], liver cancer [5], inflammations [6], cardiovascular disorders [7], diabetes mellitus (DM) [8], and neurodegeneration [9]. Thus, C. chinensis fruits might have more potential applications in healthcare products. Even so, they are always considered as waste because no information about the composition of C. chinensis fruits has been found yet. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop and validate a simple, rapid and reliable method for the identification and simultaneous quantitation of the bioactive components in C. chinensis fruits.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is known for its high speed and separation efficiency, while tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) not only presents high selectivity but also provides molecular structure elucidation. HPLC-MS/MS has become a powerful tool for the comprehensive determination of bioactive natural products [10]. Thus, HPLC-electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS/MS was employed in this work for both the identification and multicomponent analysis of C. chinensis fruits. Subsequently, the validated method was applied to analyze batches of C. chinensis fruits from different phytomorph and areas. The complex raw data were processed by principal components analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) to evaluate the quality differences among C. chinensis fruits in Wuhan, China. The work will be conducive to the efficient utilization of C. chinensis fruits.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and materials

HPLC-grade methanol and acetonitrile were purchased Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ, USA). Formic acid was purchased from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ultrapure water was purchased from Hangzhou Wahaha Group Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). Except for quercetin, gallic acid and kaempferol were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), the rest of the standard (myricitrin, quercitrin, myricetin, astragalin, methyl gallate, (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG), ellagic acid, (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and luteolin) were purchased from Chengdu Ruifensi Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). The purity of all standards was more than 98%. Unless otherwise specified, all the other reagents used in the experiment were of analytical grade.

Nine batches of C. chinensis fruits were collected from different phytomorph (clustered and lush, clustered but sparse, solitary) and areas (Wuchang, Hanyang, and Hankou) in July 2019. Samples (Wuchang-clustered-lush, Wuchang-clustered-sparse, Wuchang-clustered-sparse, Hanyang-clustered-lush, Hanyang-solitary, Hanyang-solitary, Hankou-clustered-lush, Hankou-clustered-lush, and Hankou-clustered-lush) were labeled numbers 1–9 in succession. Then they were dried at 60 °C in an oven, crushed into powders, and finally stored at −20 °C until further use.

2.2. Standard and sample preparation

The stock solutions of ten reference substances were prepared in methanol at a concentration of 503–577 μg/mL, and stored at 4 °C.

Sample for identification was prepared as follows. The C. chinensis fruit powder was weighted at 1.0 g and extracted with 100 mL of methanol/water (70:30, V/V) in an ultrasonic water bath for 45 min. The yellow filtrate was obtained after extraction and filtration. Then, the methanol was evaporated from the filtrate by spin evaporation. The residue was suspended in 4 mL water and transferred into a 10 mL centrifuge tube. After that, it was successively extracted 3 times each with 4 mL of petroleum ether and ethyl acetate. Finally, the ethyl acetate was evaporated by spin evaporation and the residue was dissolved in 2 mL methanol.

Sample for quantitation was prepared as follows. The C. chinensis fruit powder was weighted at 0.10 g and extracted with 10 mL of methanol/water (80:20, V/V) in an ultrasonic water bath for 45 min.

2.3. Instruments

The HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis was performed by using a Shimadzu LC-20AD series chromatographic system connected to a tandem MS/MS. The HPLC was equipped with two LC-20AD binary pumps, a DGU-20A degasser, a SIL-20AC autosampler and a CTO-20AC column oven. Chromatographic separation was carried out on a Sepax BR-C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 3 μm). The injection volume for all samples was set at 2 μL. MS detection was performed using an AB Sciex API4000Qtrap mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray interface (ESI) source. The source temperature was set at 3350 °C, and nebulizer and heater gas were both set at 50 psi. Ion spray voltage was −4.5 kV (4.5 kV in positive ion mode), and curtain gas was set at 35 psi. LC-ESI-MS/MS data were collected and processed by Analyst software version 1.6.2 (AB Sciex). High-resolution MS data were obtained by an UltiMate 3000 Rapid Separation Liquid Chromatography system connected to a Q Exactive Focus mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.4. Analytical conditions

2.4.1. Identification

The mobile phase was 0.1% aqueous formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B). Separations were carried out with a multistep gradient as follows: 0–20 min, 10%–40% B; 20–25 min, held at 95% B; 25–35 min, held at 10% B. The flow rate was 0.2 mL/min.

For MS detection, mass spectra operating in negative ion mode was recorded in the m/z 100–1200 range with accurate mass measurements of all mass peaks.

2.4.2. Quantitation

The mobile phase was 0.1% aqueous formic acid (A) and methanol with 0.1% formic acid (B). Separations were carried out with a multistep gradient as follows: 0–15 min, 15%–50% B; 15–22 min, 50%–60% B; 22–25 min, held at 95% B; 25–35 min, held at 15% B. The flow rate was 0.2 mL/min.

Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) was used with collision-induced dissociation to quantify the analytes. Quantitation was carried out by calculating analyte concentration from MRM peak area.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of the bioactive components from ethyl acetate extracts of C. chinensis fruits

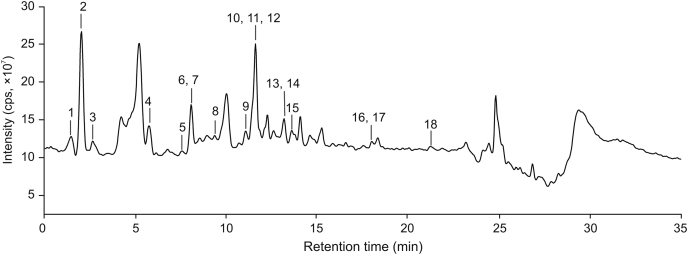

The developed method of HPLC-ESI-MS/MS realized the tentative identification of eighteen components from the ethyl acetate extracts of C. chinensis fruits, which was verified by the results of high-resolution mass spectrometry via confirmation in the molecular weight of these compounds. The results are shown in Table 1, Fig. 1 and Fig. S1. It was found that polyphenols, including phenolic acids (1, 2, 3, 4, 10), catechins (6 and 12), anthocyanins (8 and 9) and flavonoids (5, 7, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18), were the main components of structure elucidation.

Table 1.

Characterization of the compounds found in the ethyl acetat extracts of C. chinensis.

| No. | tR (min) | [M-H]-(m/z) | Formula | Tentative assignment | MS/MSa(m/z) | [M-H]-b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exptl. (m/z) | Calcd. (m/z) | Error (ppm) | ||||||

| 1 | 1.42 | 331.0 | C13H16O10 | Glucogallin | 271.0 (11), 241.0 (1), 169.0 (23), 125.0 (11) | 331.0660 | 331.0660 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 2.07 | 169.0 | C7H6O5 | Gallic acid | 125.0 (100) | 169.0126 | 169.0131 | 3.1 |

| 3 | 2.79 | 483.0 | C20H20O14 | 1, 6-bis-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose/isomer | 331.0 (30), 271.0 (95), 241.0 (2), 169.0 (13), 125.0 (10) | 483.0765 | 483.0769 | 0.8 |

| 4 | 5.86 | 183.0 | C8H8O5 | Methyl gallate | 168.0 (8), 140.0 (40), 124.0 (35), 111.1 (10) | 183.0283 | 183.0288 | 2.6 |

| 5 | 7.76 | 593.3 | C27H30O15 | Vicenin-2 | 503.3 (5), 473.2 (14), 413.3 (2), 383.3 (15), 353.2 (24) | 593.1494 | 593.1501 | 1.2 |

| 6 | 8.06 | 457.0 | C22H18O11 | EGCG | 331.0 (8), 305.0 (19), 287.0 (3), 219.0 (3), 193.0 (7), 169.0 (100), 125.1 (53), | 457.0762 | 457.0765 | 0.7 |

| 7 | 8.07 | 479.0 | C21H20O13 | Myricetin-3-O-hexose | 316.1 (57), 317.1 (21), 287.1 (10), 271.0 (11), 242.1 (1), 150.9 (1) | 479.0815 | 479.0820 | 1.1 |

| 8 | 9.38 | 729.1 | C37H30O16 | Procyanidin B–O-gallate | 711.0 (6), 577.1 (15), 559.1 (18), 451.1 (13), 407.0 (75), 289.1 (17), 245.0 (3) | 729.1442 | 729.1450 | 1.2 |

| 9 | 11.02 | 881.1 | C44H34O20 | Procyanidin B-di-O-gallate | 729.2 (34), 711.1 (9), 577.1 (7), 559.2 (14), 451.1 (7), 289.2 (6), 161.0 (1) | 881.1544 | 881.1560 | 1.8 |

| 10 | 11.42 | 301.0 | C14H6O8 | Ellagic acid | 284.1 (8), 257.0 (2), 245.0 (1), 229.0 (3), 201.1 (2), 185.0 (3) | 300.9981 | 300.9979 | 0.5 |

| 11 | 11.57 | 463.0 | C21H20O12 | Myricetrin | 316.1 (73), 287.1 (13), 271.0 (13), 179.0 (1), 151.0 (2) | 463.0867 | 463.0871 | 0.9 |

| 12 | 11.65 | 441.0 | C22H18O10 | ECG | 331.0 (13), 289.0 (89), 271.0 (9), 245.0 (17), 193.0 (16), 179.1 (6), 169.0 (100), 125.0 (64) | 441.0813 | 441.0816 | 0.8 |

| 13 | 13.02 | 317.0 | C15H10O8 | Myricetin | 193.1 (2), 179.0 (13), 151.0 (10), 137.0 (11) | 317.0292 | 317.0292 | 0.1 |

| 14 | 13.11 | 447.1 | C21H20O11 | Astragalin | 284.1 (19), 255.0 (17), 227.0 (9), 175.0 (5) | 447.0919 | 447.0922 | 0.6 |

| 15 | 13.76 | 447.1 | C21H20O11 | Quercitrin | 301.1 (52), 179.0 (4), 150.9 (4) | 447.0920 | 447.0922 | 0.5 |

| 16 | 18.03 | 285.0 | C15H10O6 | Luteolin | 241.0 (2), 199.0 (3), 175.0 (3), 150.9 (2), 133.0 (12) | 285.0396 | 285.0394 | 0.8 |

| 17 | 18.13 | 301.0 | C14H6O8 | Quercetin | 273.0 (3), 257.0 (3), 229.0 (2), 179.0 (16), 151.0 (26) | 301.0344 | 301.0343 | 0.5 |

| 18 | 21.27 | 285.0 | C15H10O6 | Kaempferol | 257.1 (1), 229.0 (2), 211.0 (2) | 285.0396 | 285.0394 | 0.8 |

Determined by HPLC-ESI-QQQtrap.

Determined by HPLC-ESI-Q Orbitrap.

Fig. 1.

Total ion chromatogram of ethyl acetate extracts of C. chinensis fruits in negative ion mode.

3.1.1. Phenolic acids

Compound 1 was tentatively identified as glucogallin attributed to the presence of the deprotonated molecule at m/z 331.0 [M-H]- and MS/MS fragments at m/z 169.0 (loss of glucoside), 125.0 (loss of glucoside and CO2), 271.0 (loss of C2H4O2), and m/z 241.0 (loss of C3H6O3) [11].

Compound 3 was tentatively identified as 1, 6-bis-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose or its isomers ([M-H]- at m/z 483.0). The MS/MS fragment at m/z 331.0 [M-H-152]- was produced by loss of galloyl group, and it followed the same fragmentation pattern as glucogallin.

Compounds 2, 4, and 10 were positively identified as gallic acid, methyl gallate, and ellagic acid, respectively. Compound 2 presented [M-H]- at m/z 169.0 with MS/MS fragment at m/z 125.0, corresponding to the neutral loss of CO2 [12]. Besides, gallic acid was the main compound identified in the ethyl acetate extracts of the C. chinensis fruits. Compound 4 exhibited [M-H]- at m/z 183.0 and typical MS/MS fragments of methyl gallate at m/z 168.0 (loss of CH3), 140.0 (loss of CH3 and CO), and 124.0 (loss of CH3 and CO2). Compound 10 showed [M-H]- at m/z 301.0 which was dissociated to give an intense MS/MS fragment at m/z 257.0 (loss of CO2), further producing a fragment at m/z 229.0 (loss of CO2 and CO), and 185.0 (loss of two CO2 and one CO) [13].

3.1.2. Catechins

Compound 6 was assigned as EGCG ([M-H]- at m/z 457.0). The fragment at m/z 169.0 indicated the existence of gallate in the structure. The fragment at m/z 331.0 was cycled after the loss of the B-ring from [M-H]-, further producing a fragment at m/z 193.0 by the retro Diels-Alder (RDA) cleavage of C-ring bonds (loss of C7H6O3). Another typical MS/MS fragment at m/z 305.0 suggested the loss of galloyl group from [M-H]-, producing fragmentation ions at m/z 219.0 (loss of CO2 and C2H2O) and 287.0 (loss of H2O). Additionally, the presence of the ion at m/z 125.1 suggested the C-ring 1, 4 retro cyclizations in the structure of fragment at m/z 287.0 and the loss of carboxyl from fragment at m/z 169.0 [14].

Compound 12 was positively identified as ECG ([M-H]- at m/z 441.00), showing the same fragmentation pattern as compound 6.

3.1.3. Anthocyanins

Compound 8 possessed a deprotonated molecule at m/z 729.1 that was dissociated to give MS/MS fragments at m/z 711.0 (loss of H2O) and 577.1 (loss of galloyl group). The fragment at m/z 577.1 further underwent the RDA cleavage and loss of H2O resulting in the fragment at m/z 407.0. The fragments at m/z 289.1 and m/z 451.1 were in keeping with quinone methide (QM) and heterocyclic ring fission (HRF) of the fragment at m/z 577.1, respectively [15]. On the strength of fragmentation data, compound 8 was tentatively identified as procyanidin B-O-gallate.

Compound 9 was tentatively identified as procyanidin B-di-O-gallate ([M-H]- at m/z 881.1). The MS/MS fragment at m/z 729.2 [M-H-152]- was obtained by loss of galloyl group from the deprotonated molecule. Subsequently, the ion at m/z 729.2 shared the same fragmentation pattern as procyanidin B-O-gallate [16].

3.1.4. Flavonoids

Compound 5 exhibited a deprotonated molecule at m/z 593.3 [M-H]- that was dissociated to give typical MS/MS fragments at m/z 503.3 (loss of C3H6O3), 413.3 (loss of two C3H6O3), 473.2 (loss of C4H8O4), 383.3 (loss of C4H8O4 and C3H6O3), and 353.2 (loss of two C4H8O4) [17]. Based on the fragmentation data, compound 5 was tentatively identified as vicenin-2.

Compound 13, myricetin, exhibited a deprotonated molecular ion at m/z 317.0 [M-H]-. The major fission was based on the RDA cleavage of C-ring bonds resulting in 1, 2 B- fragment at m/z 137.0, and 1, 2 A- at m/z 179.0, which further generated a major fragment at m/z 151.0 by loss of CO (28 Da) [18]. Equally characteristic for flavanones was the loss of the whole B-ring to produce a [M-H-B-ring]- fragment at m/z 193.1.

Compound 7 possessed a deprotonated molecule at m/z 479.0 [M-H]- that underwent both a collision-induced heterolytic and homolytic cleavage of the O-glycosidic bond producing aglycone (Y0-) at m/z 317.1, and deprotonated radical aglycone ([Y0-H]-) at m/z 316.1, whose relative abundance was higher. Furthermore, the fragment at m/z 316.1 produced two major fragments at m/z 287.1 (loss of CHO) and 271.0 (loss of CO and OH) [19,20]. According to the above fragmentation pattern, compound 7 was tentatively identified as myricetin-3-O-hexose.

Compound 11, myricetrin, presented [M-H]- at m/z 463.0 and showed the same fragmentation pattern as compounds 13 and 7.

Compound 17, identified as quercetin, presented [M-H]- at m/z 301.0 and typical MS/MS fragmentation ions of quercetin at m/z 273.0 (loss of CO), and 257.0 (loss of CO2). Furthermore, the quercetin underwent the characteristic cleavage of C-ring bonds resulting in 1, 2 A- fragment at m/z 179.0, and 1, 3 A- at m/z 151.0 [21].

Compound 15 was positively identified as quercitrin ([M-H]- at m/z 447.1). The fragment at m/z 301.1, indicating neutral losses of deoxyhexose, was the most abundant ion. The fragmentation patterns of ions at m/z 179.0 and m/z 150.9 were the same as quercetin.

Compound 14, assigned as astragalin, exhibited [M-H]- at m/z 447.1 that underwent a collision-induced homolytic cleavage of the O-glycosidic bond producing deprotonated radical aglycone ([Y0-H]-) at m/z 284.1. Furthermore, the fragment at m/z 284.1 produced two major fragments at m/z 175.0 (loss of the whole B-ring), and m/z 255.0 (loss of CHO). The latter further produced a fragment at m/z 227.0 by loss of CO [18].

Compound 16 was assigned as luteolin ([M-H]- at m/z 285.0). This compound underwent the characteristic cleavage of C-ring bonds, resulting in 1, 3 A- fragment at m/z 150.9, and 1, 3 B- at m/z 133.0. Additionally, it showed MS/MS fragment at m/z 241.0, suggesting the loss of CO and O from the C-ring of luteolin [21].

Compound 18, assigned as kaempferol, possessed a deprotonated molecule at m/z 285.0 [M-H]- that produced a fragment at m/z 257.1 [M-H-28]-, suggesting the loss of CO and the existence of fragment at m/z 229.0, indicating the loss of another CO [M-H-28-28]-. Moreover, the MS/MS fragment at m/z 211.0 indicated the loss of HCOOH from [M-H]- [22].

Twelve of the above compounds (2, 4, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18) were confirmed based on comparison of retention time and mass spectra with an authentic standard.

3.2. Optimization of extraction and analytical conditions

Different mobile phases, such as acetonitrile and methanol, were tested with various modifiers including formic acid and ammonium acetate. Several combinations of trials showed that the separation effect was better and compounds had higher responses when the mobile phase was methanol rather than acetonitrile. Moreover, the compound showed a more symmetrical peak shape when formic acid was added. Therefore, the final optimized mobile phase was determined as 0.1% aqueous formic acid (A) and methanol with 0.1% formic acid (B).

The compound-specific MRM scan parameters, including collision energy (CE), declustering potential (DP) and cell exit potential (CXP), were optimized based on the responses of the product ions in the quantitation of C. chinensis fruits (Table S1).

There are many approaches to pre-treating and extracting active constituents from C. chinensis fruits, such as ultrasonic extraction, microwave extraction, enzymatic extraction, membrane extraction and supercritical fluid extraction. If supplemented by ammonia-based pretreatments [23,24], enzymatic extraction technology can greatly improve the extraction rate of active components from natural plants. However, based on previous research [3], ultrasonic extraction was chosen in this study because of its simple and fast operation, low extraction temperature, high extraction rate, and protection of the extract structure. In order to efficiently extract the polyphenols, extraction solvent (70%, 75%, 80%, 85%, 90%, 95%, and 100% methanol), solid-liquid ratio (1:60, 1:80, 1:100, and 1:120; g/mL), and extraction time (30, 45, 60, and 75 min) were successively optimized by single-factor experiments (Fig. S1). Subsequent to the trials, the best extraction conditions were concluded as follows: The C. chinensis fruit powder was weighted at 0.10 g and extracted with 10 mL of methanol/water (80:20, V/V) in an ultrasonic water bath for 45 min.

3.3. Analytical method validation

To assess the validity of the method, validation tests were run. All the ten polyphenols (gallic acid, methyl gallate, luteolin, quercetin, myricetin, ECG, astragaline, quercitrin, EGCG, and myricetrin) showed good linearity (r > 0.999) in the corresponding concentration ranges. The results of limits of quantitation (LOQ, determined at a signal-to-noise ratio of 10) and limits of detection (LOD, determined at a signal-to-noise ratio of 3) are presented in Table 2. It suggests that the developed method for the simultaneous determination of ten polyphenols had high sensitivity.

Table 2.

Method validation.

| Compound | Calibration curve | r | LOD (ng/mL) | LOQ (ng/mL) | Precision (RSD, %) |

Repeatability (RSD, %) | Stability (RSD, %) | Recovery |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-day | Inter-day | Mean (%) | RSD (%) | |||||||

| Gallic acid | y = 1000000x+47943 | 0.9996 | 4.1 | 10.0 | 0.45 | 2.12 | 1.70 | 2.80 | 103.02 | 3.64 |

| Methyl gallate | y = 1000000x+18437 | 0.9997 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 0.92 | 2.98 | 5.61 | 2.22 | 115.05 | 4.07 |

| Luteolin | y = 2000000x+30415 | 0.9998 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.70 | 6.92 | 6.22 | 2.94 | 106.82 | 6.16 |

| Quercetin | y = 528108x-957957 | 1.0000.0000 | 2.9 | 4.8 | 1.80 | 6.07 | 2.11 | 4.88 | 90.29 | 4.66 |

| Myricetin | y = 651452x-7138 | 0.9998 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 3.01 | 7.72 | 3.03 | 4.43 | 102.17 | 6.82 |

| ECG | y = 494967x+20522052 | 1.0000.0000 | 5.3 | 22.1 | 1.38 | 5.08 | 0.90 | 3.69 | 107.22 | 4.94 |

| Astragalin | y = 837204x+65286 | 0.9996 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.27 | 4.46 | 3.20 | 3.57 | 110.32 | 4.69 |

| Quercitrin | y = 746261x+3612 | 0.9999 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 1.78 | 3.21 | 3.31 | 3.67 | 100.65 | 3.42 |

| EGCG | y = 585905x+410 | 1.0000.0000 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 0.76 | 3.21 | 1.07 | 2.79 | 96.47 | 3.61 |

| Myricetrin | y = 1000000x+11877 | 0.9998 | 0.5 | 2.2 | 1.25 | 2.80 | 1.41 | 3.34 | 101.92 | 2.23 |

Intra-day and inter-day precisions were evaluated by five replicate determinations of standards on the same day and three consecutive days, respectively. Repeatability test was run by analyzing nine samples at three different concentrations of 50%, 100%, and 150% levels which were independently prepared and analyzed in triplicate. For the stability test, the samples were extracted and stored at 15 °C, and analyzed at five time points (0, 4, 8, 12, and 16 h). The RSD values were calculated for the evaluation of precision, repeatability, and stability. The results were satisfactory and are presented in Table 2.

To assess the accuracy of the proposed method, the recovery was investigated as follows: 0.05 g of the C. chinensis fruit powder spiked with an accurate amount of mixed reference substances was extracted using the developed method, and then submitted to the complete proposed procedure. As can be seen in Table 2, the developed analytical method was accurate with recoveries of 90.29%–115.05%.

3.4. Quantification and statistical multivariate approach

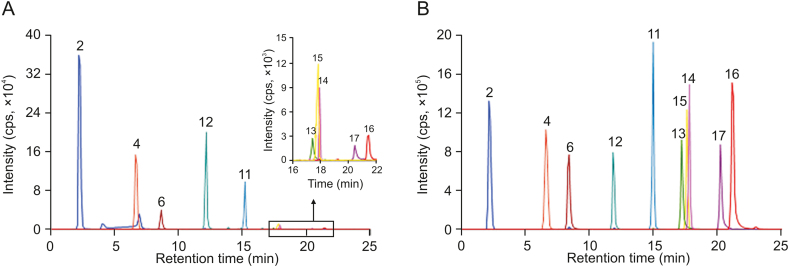

The developed HPLC-ESI-MS/MS method was applied for quantitative determination of ten polyphenols (gallic acid, methyl gallate, luteolin, quercetin, myricetin, ECG, astragalin, quercitrin, EGCG, and myricetrin) in nine batches of C. chinensis fruits. The MRM chromatograms are displayed in Fig. 2, and the contents are summarized in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Typical MRM chromatograms of ten polyphenols in (A) extracts and (B) standard solutions. Peak identification: 2: gallic acid; 4: methyl gallate; 6: EGCG; 11: myricetrin; 12: ECG; 13: myricetin; 14: astragalin; 15: quercitrin; 16: luteolin; 17: quercetin.

Table 3.

Content (mg/g) comparisons of ten compounds in nine batches of C. chinensi fruits.

| Batches | Gallic acid | Methyl gallate | Luteolin | Quercetin | Myricetin | ECG | Astragalin | Quercitrin | EGCG | Myricetrin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.02 | 3.57 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 3.07 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 2.08 | 0.40 |

| 2 | 1.56 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 6.96 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 1.33 | 0.47 |

| 3 | 1.64 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 5.08 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 1.85 | 0.58 |

| 4 | 3.44 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 2.50 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 1.02 | 0.28 |

| 5 | 1.91 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 5.70 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.85 | 0.75 |

| 6 | 1.37 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 9.15 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 2.19 | 1.38 |

| 7 | 4.42 | 1.42 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 3.09 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 1.16 | 0.30 |

| 8 | 4.96 | 1.35 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 3.93 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 1.30 | 0.58 |

| 9 | 5.09 | 2.08 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 4.44 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.30 |

Under the optimized extraction conditions of this study there were a wide variety of polyphenols in the ethyl acetate extracts of nine batches of C. chinensis fruits. It showed that gallic acid was the most abundant rather than flavonoids, which are the only bioactive components previously reported in the related research of C. chinensis fruits [3]. Moreover, it has been reported that gallic acid has multiple pharmacological activities due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potentials, such as antibacterial and anticancer effects, and resistance to gastrointestinal diseases, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic diseases, and neurological diseases [25]. It suggests that C. chinensis fruits have more extensive bioactivities and more applications. Therefore, the determination of gallic acid is used for the quality control of many Chinese traditional medicine in the Chinese Pharmacopeia.

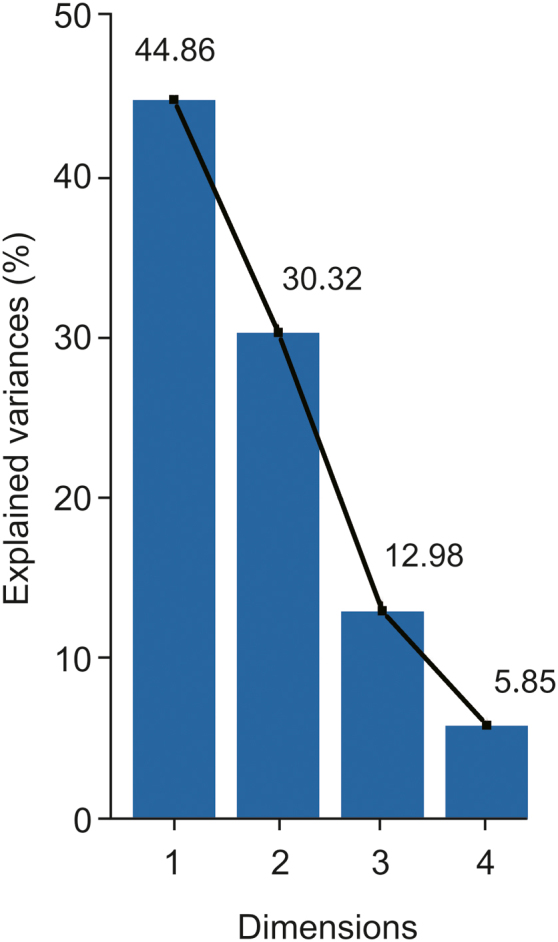

PCA, a descriptive multivariate statistical analysis method for visualization and reduction of data set dimension [26], was performed with SAS version 9.1 in this study to prioritize or evaluate nine batches of samples in terms of the content of specific bioactive components. As can be seen in Fig. 3, the first three principal components showed the best clustering with a total variance of 88.1%. Therefore, in Table 4, just the eigenvectors of prin1, prin2 and prin3 were focused. The larger the eigenvector, the more information the original variable contributing to the principal component. The eigenvectors in Table 4 indicates that detection of myricetrin, ECG, quercitrin, methyl gallate, quercetin, myricetin, and gallic acid might be used for the quality control of C. chinensis fruits.

Fig. 3.

PCA scree plot. The scree plot shows how much variation each PC captures from the data. The cutting-off point indicates the first three PCs capture most of the information, and then the rest can be ignored without losing anything important.

Table 4.

Eigenvectors of the four maximum eigenvalues of the four maximum eigenvalues of correlation coefficient matrix.

| Variable | Compounds | Eigenvectorsa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prin1 | Prin2 | Prin3 | Prin4 | ||

| X1 | Gallic acid | −0.316845 | 0.289978 | 0.449243 | 0.037814 |

| X2 | Methyl gallate | −0.220481 | 0.415437 | 0.393227 | 0.264968 |

| X3 | Luteolin | 0.242207 | 0.335556 | −0.383323 | 0.477753 |

| X4 | Quercetin | 0.293373 | −0.270439 | 0.476144 | 0.178633 |

| X5 | Myricetin | 0.277019 | −0.293677 | 0.453918 | 0.327893 |

| X6 | ECG | 0.439049 | −0.101339 | −0.098127 | 0.088916 |

| X7 | Astragalin | 0.331443 | 0.319937 | 0.159990 | −0.504100 |

| X8 | Quercitrin | 0.211694 | 0.487103 | 0.124810 | −0.223715 |

| X9 | EGCG | 0.275319 | 0.348452 | −0.072616 | 0.413034 |

| X10 | Myricetrin | 0.454195 | 0.005049 | 0.088239 | −0.279324 |

The result indicates that myricetrin and ECG account for prin 1, quercitrin and methyl gallate account for prin 2, while quercetin, myricetin and gallic acid account for prin 3.

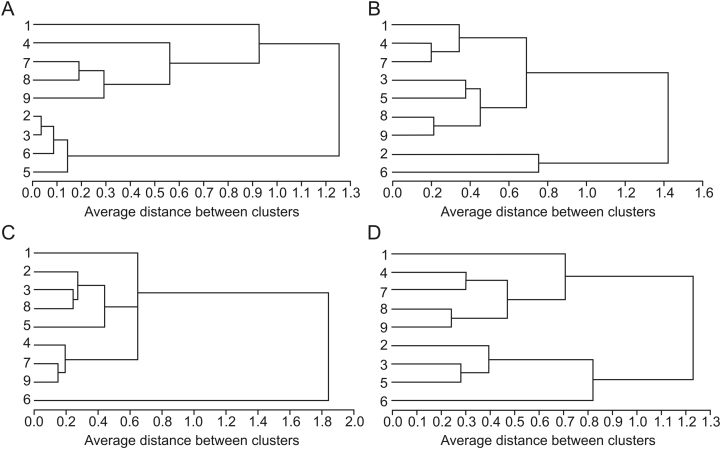

HCA, another multivariate analysis method for studying classification problems, has been widely used for quality evaluation of traditional Chinese medicines [27]. Performed with SAS version 9.1, HCA was employed in this study to classify the 9 batches of samples by the content of 10 bioactive components. Fig. 4 displays the dendrograms of nine batches of samples based on the content of different selected variables (i.e., phenolic acids, catechins, flavonoids, and all ten components). When the content of phenolic acids and all ten components was used as the variable in turn (Figs. 4A and D), the clustering results were similar. Assuming that a proper level of distance had been selected, the nine batches of samples could be divided into two main clusters: batches 1, 4, 7, 8, and 9 were in cluster A; batches 2, 3, 5, and 6 were in cluster B. Obviously, this classification was based on different phytomorph (grow singly or clustered, lush or sparse) rather than area, which indicates the importance of cultural method of medicinal plants to the content of bioactive components. It also reminds us that the content of phenolic acids and all ten components might be used to differentiate different phytomorph.

Fig. 4.

Dendrogram of HCA for nine batches of C. chinensis samples. Dendrogram resulted from the content of ten polyphenols in the tested samples. (A) phenolic acids, (B) catechins, (C) flavonoids, and (D) all ten components.

4. Conclusion

Eighteen polyphenols in C. chinensis fruits were quickly identified, and the mass fragmentation patterns of them were summarized. Moreover, a HPLC-MS/MS method to simultaneously quantify ten polyphenols in C. chinensis fruits was developed. The developed method was validated and showed high sensitivity, reproducibility and accuracy. It can be used for the determination of polyphenols in nine batches of C. chinensis fruits from different phytomorph and areas. The results of PCA and HCA realized visualization and reduction of data set dimension and provided the theoretical reference for the quality evaluation of C. chinensis fruits.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 82073808, 81872828, and 81573384).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2020.07.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Li Y., Zhang D.M., Yu S.S. A new stilbene from Cercis chinensis Bunge. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2005;47:1021–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J.T. Antibacteral activity and antioxidant activity in vivo of red pigment from flowers of Cercis chinensis Bge. Food Sci. Technol. 2011;36:238–241. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y. Flavonoids extracted from Cercis chinensis Bunge fruit with an orthogonal test and its antioxidant. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2016;47:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rakers C., Schwerdtfeger S.M., Mortier J. Inhibitory potency of flavonoid derivatives on influenza virus neuraminidase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:4312–4317. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J.K., Wu Y.P., Zhao X.Y. Chemopreventive effect of flavonoids from Ougan (Citrus reticulata cv. Suavissima) fruit against cancer cell proliferation and migration. J. Funct. Foods. 2014;10:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen L., Teng H., Jia Z. Intracellular signaling pathways of inflammation modulated by dietary flavonoids: the most recent evidence. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2018;58:2908–2924. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1345853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel R.V., Mistry B.M., Shinde S.K. Therapeutic potential of quercetin as a cardiovascular agent. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;155:889–904. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeon J.Y., Bae Y.J., Kim E.Y. Association between flavonoid intake and diabetes risk among the Koreans. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2015;439:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maher P. The potential of flavonoids for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3056–3074. doi: 10.3390/ijms20123056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao X.Y., Hu F.L., Chen Z.L. Identification and quantitation of the bioactive components in Osmanthus fragrans fruits by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:359–367. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wen X.X., Luo K.D., Xiao S. Qualitative analysis of chemical constituents in traditional Chinese medicine analogous formula cheng-Qi decoctions by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2016;30:301–311. doi: 10.1002/bmc.3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newsome A.G., Li Y.C., van Breemen R.B. Improved quantification of free and ester-bound gallic acid in foods and beverages by UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016;64:1326–1334. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiste R.C., Mercadante A.Z. Identification and quantification, by HPLC-DAD-MS/MS, of carotenoids and phenolic compounds from the Amazonian fruit Caryocar villosum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:5884–5892. doi: 10.1021/jf301904f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miketova P., Schram K.H., Whitney J. Tandem mass spectrometry studies of green tea catechins. Identification of three minor components in the polyphenolic extract of green tea. J. Mass Spectrom. 2000;35:860–869. doi: 10.1002/1096-9888(200007)35:7<860::AID-JMS10>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellstrom J., Sinkkonen J., Karonen M. Isolation and structure elucidation of procyanidin oligomers from saskatoon berries (Amelanchier alnifolia) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:157–164. doi: 10.1021/jf062441t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu L.W., Kelm M.A., Hammerstone J.F. Screening of foods containing proanthocyanidins and their structural characterization using LC-MS/MS and thiolytic degradation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:7513–7521. doi: 10.1021/jf034815d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva D.B., Turatti I.C.C., Gouveia D.R. Mass spectrometry of flavonoid vicenin-2, based sunlight barriers in Lychnophora species. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4309–4316. doi: 10.1038/srep04309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pascale R., Bianco G., Cataldi T.R.I. Investigation of the effects of virgin olive oil cleaning systems on the secoiridoid aglycone content using high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2018;95:665–671. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ablajan K., Abliz Z., Shang X.Y. Structural characterization of flavonol 3,7-di-O-glycosides and determination of the glycosylation position by using negative ion electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2006;41:352–360. doi: 10.1002/jms.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hvattum E., Ekeberg D. Study of the collision-induced radical cleavage of flavonoid glycosides using negative electrospray ionization tandem quadrupole mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2003;38:43–49. doi: 10.1002/jms.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsimogiannis D., Samiotaki M., Panayotou G. Characterization of flavonoid subgroups and hydroxy substitution by HPLC-MS/MS. Molecules. 2007;12:593–606. doi: 10.3390/12030593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X.F., Zhao X., Gu L.Q. Simultaneous determination of five free and total flavonoids in rat plasma by ultra HPLC-MS/MS and its application to a comparative pharmacokinetic study in normal and hyperlipidemic rats. J. Chromatogr. B. 2014;953:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao C., Shao Q.J., Ma Z.Q. Physical and chemical characterizations of corn stalk resulting from hydrogen peroxide presoaking prior to ammonia fiber expansion pretreatment. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016;83:86–93. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao C., Qiao X.L., Shao Q.J. Synergistic effect of hydrogen peroxide and ammonia on lignin. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020;146:112177–112184. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahkeshani N., Farzaei F., Fotouhi M. Pharmacological effects of gallic acid in health and diseases: a mechanistic review, Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019;22:225–237. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2019.32806.7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zengin G., Llorent-Martinez E.J., Sinan K.I. Chemical profiling of Centaurea bornmuelleri Hausskn. aerial parts by HPLC-MS/MS and their pharmaceutical effects: from nature to novel perspectives. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2019;174:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiu F., Wu S., Lu X.R. Quality evaluation of the artemisinin-producing plant Artemisia annua L. based on simultaneous quantification of artemisinin and six synergistic components and hierarchical cluster analysis. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018;118:131–141. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.