Abstract

A-to-I RNA editing, contributing to nearly 90% of all editing events in human, has been reported to involve in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) due to its roles in brain development and immune regulation, such as the deficient editing of GluA2 Q/R related to cell death and memory loss. Currently, there are urgent needs for the systematic annotations of A-to-I RNA editing events in AD. Here, we built ADeditome, the annotation database of A-to-I RNA editing in AD available at https://ccsm.uth.edu/ADeditome, aiming to provide a resource and reference for functional annotation of A-to-I RNA editing in AD to identify therapeutically targetable genes in an individual. We detected 1676 363 editing sites in 1524 samples across nine brain regions from ROSMAP, MayoRNAseq and MSBB. For these editing events, we performed multiple functional annotations including identification of specific and disease stage associated editing events and the influence of editing events on gene expression, protein recoding, alternative splicing and miRNA regulation for all the genes, especially for AD-related genes in order to explore the pathology of AD. Combing all the analysis results, we found 108 010 and 26 168 editing events which may promote or inhibit AD progression, respectively. We also found 5582 brain region-specific editing events with potentially dual roles in AD across different brain regions. ADeditome will be a unique resource for AD and drug research communities to identify therapeutically targetable editing events.

Significance: ADeditome is the first comprehensive resource of the functional genomics of individual A-to-I RNA editing events in AD, which will be useful for many researchers in the fields of AD pathology, precision medicine, and therapeutic researches.

Keywords: A-to-I RNA editing, Alzheimer’s disease, protein recoding, alternative splicing, miRNA regulation

Introduction

A-to-I RNA editing is an important transcriptional modification carried out by adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADAR) [1]. It can alter the protein-coding capacity, generate diverse protein isoforms and change the cellular fate of RNA and its likelihood of being translated [2]. Previous studies have reported its contribution to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), due to its roles in brain development and immune regulation [3–5]. For example, the most well-known A-to-I RNA editing case is the Q/R site in GluA2. The deficient editing frequency of this site is known to be correlated with synapse loss, neurodegeneration and behavioral impairments involved in AD [6]. Another well-studied case is the R/G site in GLuA2-4. Editing at this site may affect the rate of channel desensitization and recovery from it, to influence excitatory synaptic transmission and neuronal cell death [3, 7]. Therefore, systematic investigation of the functions of A-to-I RNA editing may provide potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for AD from a novel angle.

However, to date, there was no study covering the deep functional annotations of individual A-to-I RNA editing events in a big AD population. In this study, we detected A-to-I RNA editing events across ~1500 AD samples and controls from three representative AD studies, ROSMAP [8], MayoRNAseq [9] and MSBB [10]. Then we performed the systematic and intensive bioinformatics analyses, to study the potential AD mechanisms related to A-to-I RNA editing events.

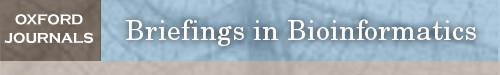

These analyses were conducted according to the pipelines shown in Figure 1. First, we identified AD/control-specific and AD stage-associated RNA editing events, showing differential editing frequencies in AD or increasing/decreasing editing levels along with the AD progression. Then we analyzed the potential editing events that might lead to the differential expressions of AD-related genes between RNA-edited samples versus wild-type samples and may involve in some AD-related pathways. Furthermore, we studied the editing events in the coding regions that might lead to the potential loss-of-function of some AD-related proteins, and RNA editing events in the splicing sites that might cause the altered splicing patterns of AD-related genes. Last, we deeply investigated the effects of RNA editing events on miRNA regulations, which would result in the differential expressions of the downstream AD-related genes. All these results are available at https://ccsm.uth.edu/ADeditome/, a reference for the studies assessing the roles of A-to-I RNA editing events in AD pathogenesis and their potential as AD targets.

Figure 1 .

The flowchart of this study. It describes the used AD cohorts, multi-omics data analyses, functional annotation of A-to-I RNA editing events and the potential AD mechanism related to A-to-I RNA editing events. The AD cohorts panel shows the number of AD samples and controls from nine brain regions. For these multi-region and multi-cohort-based AD samples, we performed multiple functional annotations using diverse bioinformatics approaches. Through these analyses, we identified multiple potential mechanisms related to the A-to-I RNA editing events in AD.

Methods

Samples and sequencing data

We downloaded clinical information, RNA sequencing and whole-genome sequencing of 1524 AD and control samples from AMP-AD [11]. They spanned nine brain regions, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), head of caudate nucleus (AC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), cerebellum (CER), temporal cortex (TCX), frontal pole (FP), inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), parahippocampal gyrus (PG) and superior temporal gyrus (STG).

Detection of A-to-I RNA editing

With all the samples from three cohorts, the first step for us is to regenerate individual bam files by STAR using hg38 (GENCODE v.32) as the reference [12] and then detect RNA editing events by the script of REDItoolKnown.py (REDItools) [13] with default setting (e.g. minimal read coverage, 10; minimal quality score, 30; and minimal mapping quality score, 255). To ensure the confident identification of A-to-I RNA editing events, we focused on known editing sites from REDIportal (January 2020), removed germline SNP data, and filtered out the candidates with supporting reads under three or editing frequency less than 0.1. Finally, we analyzed the distributions of these detected editing events in different genomic locations and repeats by ANNOVAR [14] and the stability alterations of the transcripts being edited by RNAfold (ViennaRNA 2.4.14) [15].

Analysis of editing frequency

To uncover potential AD-related editing, we studied the frequencies of all the editing events between AD and control. Then we defined an AD-specific RNA editing site if it occurred only in AD with more than five edited samples or showed significantly higher editing frequencies (P < 0.01) in AD samples, and vice versa for control-specific RNA editing site. Next, we analyzed the correlations between editing frequencies and AD stage information (Braak score, P < 0.05, and |R| > 0.3), to identify the disease progression-associated RNA editing sites. Last, we focused on the RNA editing sites in 1556 AD-related genes (Table S1), which were collected from The International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP) [16], AMP-AD and some literature [17–22], in order to analyze the possible effects of editing on AD from the following aspects in section 2.

Analyzing the RNA editing effects on gene expression and pathways

To study the effects of RNA editing on gene expressions, we first calculated the expression levels on the basis of the regenerated individual bam files by RSEM [23]. Then we analyzed differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between RNA-edited and non-edited samples across the nine brain regions (P < 0.05 and |logFC| > 1), as well as between AD and control samples (P < 0.05 and |logFC| > 0.3). Further, to infer the potentially involved AD-related cellular processes of those editing events, Enrichr [24] was used to study the enriched pathways of DEGs.

Analyzing the RNA editing effects on protein recoding and functions

For the RNA editing events in the coding regions, we used ANNOVAR to detect the changes of amino acid sequence caused by the non-synonymous and stop-loss editing sites. Then their deleterious effects on protein functions were assessed by SIFT [25], Polyphen2 [26] and PROVEAN [27].

Analyzing the RNA editing effects on the alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs

To study the effects of RNA editing events on splicing, we first detected 296 735 exon skips, 186 661 alternative 3′ splice sites, 118 826 alternative 5′ splice sites, 179 251 intron retentions and 43 029 mutually exclusive exons in the regenerated individual bam files by SplAdder [28]. Then we overlapped RNA editing sites with 5′-donor splice sites (5′-ss) and 3′-acceptor splice sites (3′-ss) around both of the reference exons and predicted new exons. The 5′-ss is a 9-mer region of 3 nucleotides (nt) in the exon and 6 nt in the intron, while 3′-ss is a 23-mer region of 3 nt in the exon and 20 nt in the intron based on splicing research [29]. MaxEntScan method proposed in that study was also used here to estimate the changes of splice site strength for sequences being edited. To further validate the influence of RNA editing events on splicing patterns, we also compared the percent spliced in (PSI) values between RNA-edited and non-edited samples.

Analyzing of the RNA editing effects on miRNA regulation

For the editing sites in lncRNAs, mRNA 3’ UTRs and miRNA seed regions, we used TargetScan [30] and miRanda [31] to detect the miRNA binding targets for reference sequences remaining unchanged or being edited. Based on the predicted miRNA–lncRNA/mRNA 3’ UTR interactions, we defined the gain of miRNA binding targets as the interactions existed in the RNA-edited sequences but not in the non-edited sequences supported by both tools and vice versa for the loss of miRNA binding targets. Furthermore, we checked the expression levels of competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) (P < 0.05, |logFC| > 1) which were targeted by the same miRNA in the RNA-edited and non-edited groups, to discover the altered miRNA regulations caused by these RNA editing events.

Results

Overview of RNA editing sites

Through our RNA editing prediction pipeline, we identified 1676 363 A-to-I RNA editing sites in 1524 samples across nine brain regions. Out of these ~1.6 M RNA editing sites, only 0.22% were in the exonic regions and the majority of those (93.77%) were located in Alu repeat elements (Figure S1). This finding shows an editing preference for non-coding and Alu regions similar to in GTEx and TCGA [32]. Then we continue to analyze the influence of these editing events on RNA structure, gene expression, protein recoding, alternative splicing and miRNA regulation. Their effects on the changes in the secondary structure revealed that 89.77% (10 931/12 176) transcripts had significantly reduced minimum free energy (MFE) values after being edited (Figure S1). This phenomenon is accorded with the contributions of editing to RNA stability introduced in a previous study [33]. Furthermore, to correlate the potential roles of these editing events to AD, the other four effects were studied deeply in the following parts together with the editing frequencies analysis.

RNA editing frequency analysis identified AD/control-specific and disease-associated editing events

The differences in editing frequencies across the diverse stages of AD pathology and controls can notice the aberrant editing events responsible for AD occurrence and progression. Here, after checking the editing frequencies between AD samples and controls, we identified 102 246 and 23 580 editing events showing AD- and control-specific frequencies, respectively, across 7687 genes (Table S2). Next, through correlation studies with different disease stages, we identified 16 613 and 6732 editing events showing positive and negative associations with AD stages, respectively, in 3114 genes (Table S3). Among those, 12 459 and 4947 editing events have significantly higher or lower frequencies, respectively, both in AD compared to controls, and also in more server AD conditions.

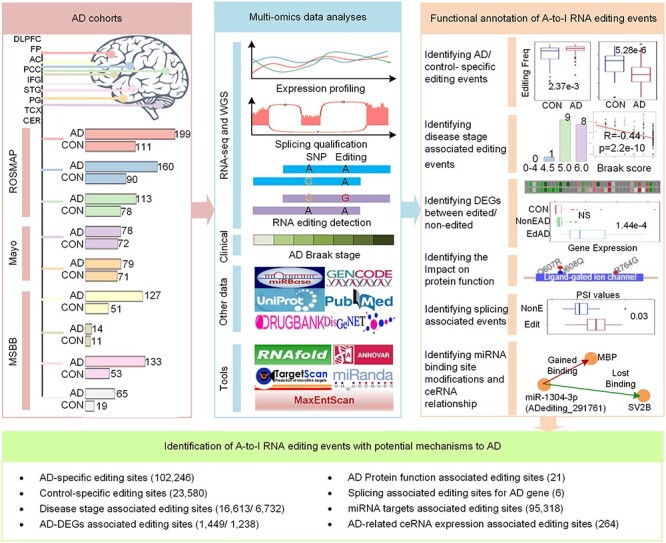

The RNA editing events showing AD-specific frequencies or positive AD-stage associations could be potential pathogenic biomarkers of AD. For example, an RNA editing event in chr14: 94618517 (ADediting_461090) of SERPINA3 occurred under the severe AD conditions only (Braak > 4.0, Figures 2A and S2) in the TCX region. This event is associated with the upregulation of the edited gene (Figure S2). Since this gene is highly expressed in AD compared to control (P = 0.02), and its overexpression is correlated with Aβ assembly promotion and inflammatory conditions [34–36], we suggest this RNA editing event as a potential biomarker of severe AD condition. Another case is the famous Q/R editing site in chr4: 157336723 (ADediting_1112899) of GRIA2. All AD samples in the CER region were edited in this position with frequencies close to 1.0, significantly higher than controls with a P-value of 2.37e-3 (Figures 2 and S3). Furthermore, this event is related to the upregulation of GRIA2 (P = 3.8e-8 and R = 0.43), which mostly happened in AD patients (P = 0.01), specifically in the patients with the severe condition (P = 1.0e-4, R = 0.37) as shown in Figure S3. Thus, high editing levels of this site in the CER region might influence the excitatory neurotransmission function of GRIA2 to have an unfavorable effect on AD.

Figure 2 .

The editing events showing AD or control specific frequencies and positive or negative associations with AD stages. (A) The number of edited samples for AD-specific editing sites only occurred in AD group across nine brain regions. ADediting_461090 in SERPINA3 was edited only in the AD samples for the CER brain region. (B) Differential editing frequencies between AD samples and controls across nine brain regions. Two editing sites in GRIA2 and ADediting_454734 in NRXN3 were significantly down-edited in AD samples compared to controls. (P < 0.01 and |EditingAD-EditingCON|>0.1) (C) RNA editing events that are correlated with AD stages across nine brain regions. Two editing sites in GRIA2 and ADediting_454734 in NRXN3 were negatively associated with the AD stages (P < 0.01, |R|>0.3). (D) GRIA2 had two editing events that were differentially edited in AD samples compared to controls and significantly associated with AD stages.

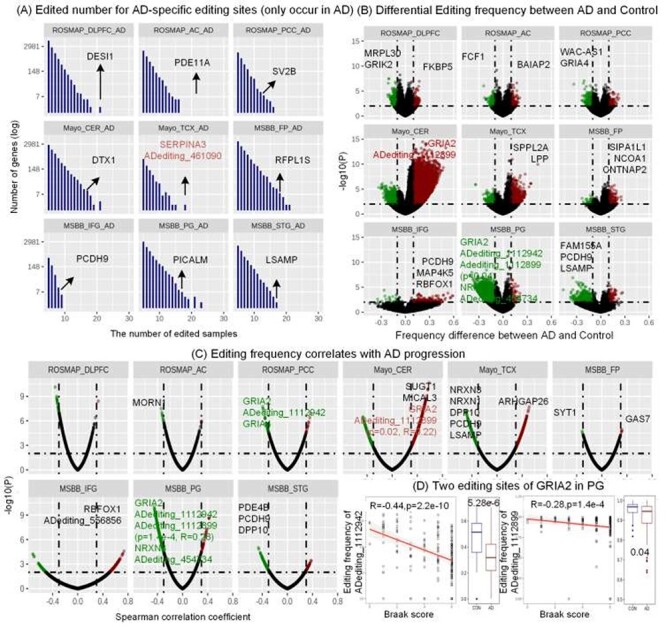

On the other hand, the upregulation of editing events with control-specific frequencies and negative AD-stage associations may have anti-disease effects on AD. They include RNA editing events in chr4: 157360142 (ADediting_1112942) and chr4: 157336723 (ADediting_1112899) of GRIA2, and chr14: 79181880 (ADediting_454734) of NRXN3 in the PG region. Their editing frequencies significantly reduced along with the ascending severity of the AD condition (Figures 2, 3A,B, S4). The two editing events in GRIA2 have been reported to be necessary for the regulation of Ca2+ permeation into the excitable cells and the enhancement of channel desensitization rate [37, 38]. Their deficient frequencies may have relationships with the dysregulated synapse functions involved in AD. Another case is a new editing event, which is associated with the upregulation of NRXN3 (Figure S4). Since the low expression of NRXN3 has been reported to increase the risk of AD pathogenesis [39], this editing event is considered as reversing the AD risk, which might provide the protection roles for the synaptic functions of NRXN3.

Figure 3 .

DEGs between RNA-edited and non-edited samples and potentially involved pathways. (A-B) Two editing events in GRIA2. We checked the correlations between editing levels and GRIA2 expressions, and differences of GRIA2 expressions between RNA-edited and non-edited groups, and between AD and control groups. (C) DEGs across nine brain regions. (D) Selection of AD-related to DEGs. (E) Enriched biological processes of overlapped DEGs between RNA-edited and non-edited groups and between AD and control samples. The red fonts present the AD-related pathways.

In this study, we discovered the dual roles of ADediting_1112899, the notable case of Q/R editing in GluA2 (synonym GRIA2), in different brain regions. Previous studies proposed the upregulating of editing frequency at this site as a novel therapeutic target for treating cell death and memory loss in AD [6,40]. We would suggest the brain region-specific influence of the same editing event, and the possible negative effects of the proposed therapeutic targets.

RNA editing events may regulate the expression of AD related genes and involve in AD related pathways

From the analyses above, we found that the frequencies of several RNA editing events were associated with the expressions of their host genes involved in AD. To systematically analyze the potential contributions of these editing events to the expression levels of genes, we performed the DEG analysis between RNA-edited and non-edited AD samples (Figure 3C). This result was combined with the DEGs between AD and controls to discover the promotion or remission influences of RNA editing events on AD condition. Then we performed the enrichment analysis on the overlapped DEGs to understand the functional effects of these RNA editing events in the key pathways related to AD.

As shown in Figure 3D, we first discovered 37 468 and 35 864 editing events that would cause the upregulated/downregulation of 3658 and 3426 genes, respectively. Then according to the aberrant gene expressions in AD compared to control, we identified 2411 and 6097 editing events that would upregulate or downregulate the abnormally high or low expressions, respectively, including 1449 events in 131 AD-related genes (Table S4) such as ADediting_461090 of SERPINA3 in the TCX region. Since these editing events seem to cause or increase the aberrant expressions in AD, they may have the potential to worsen the AD condition. On the contrary, there are 5668 and 1389 editing events that would upregulate or downregulate the abnormally low or high expressions, respectively, including 1238 events in 109 AD-related genes such as ADediting_1112899 of GRIA2 and ADediting_454734 of NRXN3 in the PG region. Due to the possible roles of these editing events to reverse the abnormal expressions in AD, they may have protection effects from AD.

It is noteworthy that there are nine editing events showing brain region-specific influences on the aberrant gene expressions. We would suggest taking extra caution to study these editing events as therapeutic targets, including RNA editing sites in chr4: 157336783, 157336984 and 157336985 (ADediting_1112901, ADediting_1112903 and ADediting_1112904) of GRIA2 with dual effects in the CER and STG regions. ADediting_1112899 mentioned before is not contained in these editing sites, due to it is 100% edited in the CER-AD group, but it still needs to be considered carefully.

As shown in Figure 3E and Table S5, many of the enriched biological pathways of these DEGs were involved in brain development or AD. For example, glutamatergic synaptic abnormalities are the early events in AD [41], agents that enhance the cAMP signaling pathway could reverse the risks associated with higher Aβ levels [42], and mishandling calcium signaling in neurons will trigger synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration [43]. They all showed the potential of RNA editing events to involve in AD-related pathways.

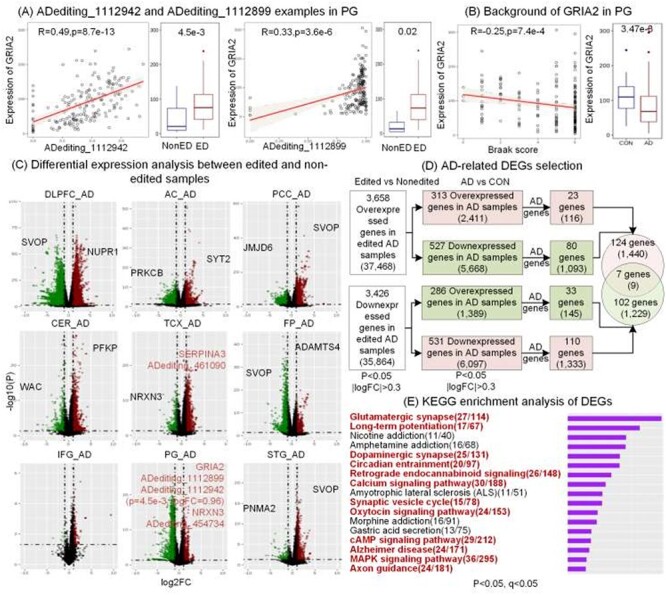

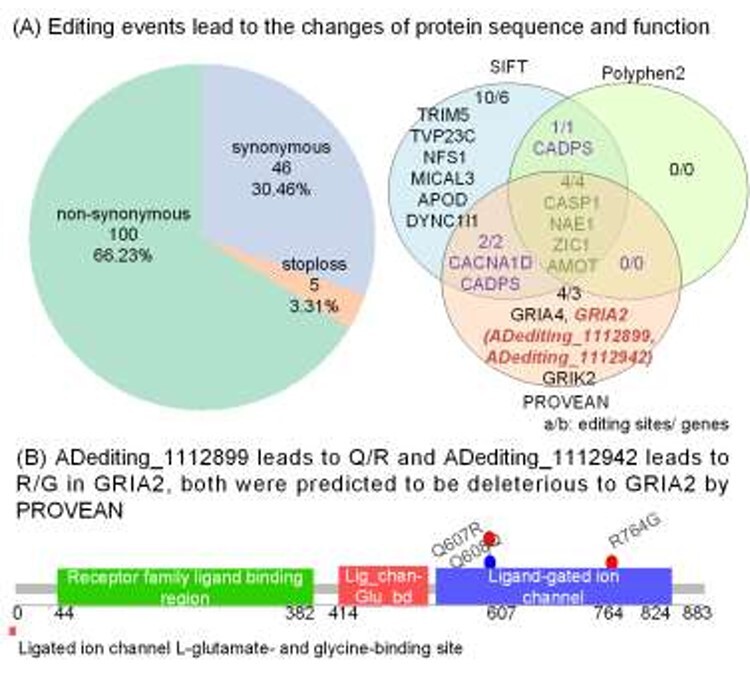

RNA editing events in coding sequences modified functions of AD-related proteins

RNA editing events in the protein-coding regions can alter the amino acid sequences and have a chance to influence the protein functions. To study this, we first mapped the editing sites in the coding regions and then identified 2178 non-synonymous and 92 stop-loss editing events. Among them, 100 non-synonymous and five stop-loss editing events will change the amino acid sequences of 47 AD proteins (Figure 4A, Table S6). Out of these, 21 editing sites were recognized to have impacts on the biological functions of 15 AD proteins by at least one of the annotation tools such as SIFT, Polyphen2 and PROVEAN (Figure 4A). The genes encoding these proteins included three glutamate receptor genes (GRIA2, GRIA4 and GRIK2), and one voltage-gated channel gene (CACNA1D), which mediate the entry or permeability of calcium ions into excitable cells [37,44,45]. RNA editing sites in these genes might influence calcium-dependent processes, such as hormone or neurotransmitter release. Specifically, ADediting_1112899 causing Q/R changes in GRIA2 (Figure 4B) makes AMPA receptors to be Ca2+-impermeable, and eventually regulate the calcium influx together with other GRIA1/3/4 genes. The lower frequency of this site may lead to excessive calcium and cell death, loss of dendritic spines, learning and memory impairments, and have a link with neurodegenerative processes [3, 6, 46].

Figure 4 .

Functional annotation of RNA editing events in protein-coding regions in AD-related genes. (A) Functional composition of the identified RNA editing events in AD-related genes based on SIFT, Polyphen2 and PROVEAN. The genes shown in the Venn diagram are related with AD. (B) Two editing events on the protein domain structures of GRIA2.

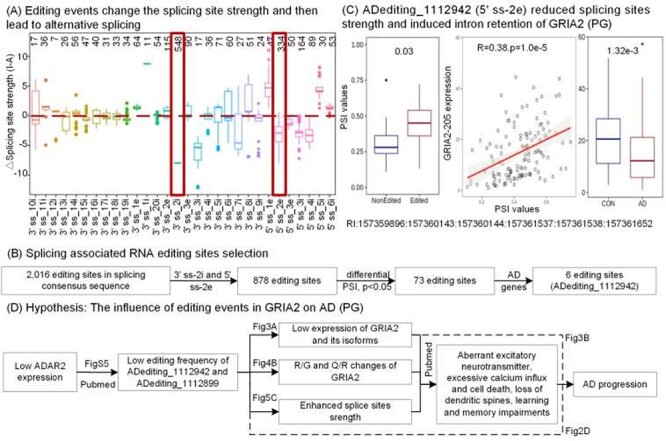

RNA editing events influence the alternative splicing patterns of AD-related genes

RNA editing sites in the alternatively spliced exon regions can differentiate the splice site strength and eventually affect the selection of splicing positions. For this aim, we overlapped all editing sites with the genomic coordinates of 3′-ss and 5′-ss around the exon junction boundaries in the three AD cohorts. Then we identified 1264 3′-ss and 760 5′-ss editing sites in total. They showed diverse impacts on the splice site strength across 970 genes (Figure 5A), due to their different locations in the splicing related sequences. We also observed that the second positions from the exon-intron junctions (3′-ss-2i and 5′-ss-2e) were edited more than other locations. These 3′-ss-2i and 5′-ss-2e editing events altered the canonical splicing pattern of AG-GU and could make a dramatic reduction of splice site strength as shown in Figure 5A.

Figure 5 .

RNA editing events and alternative splicing. (A) Distribution of the changes of splicing site strength caused by RNA editing across diverse locations in the splice site sequence. The x-axis represents the locations of editing sites in the splice site sequence. For example, 3’ss_2i denotes the editing sites reside in the second position in intron from 3′ exon-intron junction boundaries. The y-axis shows the changes of splicing site strength predicted by MaxEntScan. (B) Pipeline for identifying the splicing event-associated RNA editing event. (C) One RNA editing event of GRIA2 that is associated with the intron retention event with differential PSI values between RNA-edited and non-edited AD groups. This event was positively correlated with the expressions of GRIA2–205 which are lower in AD samples compared to controls. (D) A hypothetic story for explaining the relationship between RNA editing events in GRIA2 and AD from various aspects.

Furthermore, out of these editing events, 73 cases significantly changed the PSI values of the alternative splicing events (P < 0.05, |diff| > 0.1), including six editing events in AD-related genes (Figure 5B, Table S7). For example, Figure 5C shows the differential PSI values caused by ADediting_1112942 in 5′-ss-2e of GRIA2. It provides clear evidence that this editing event induced the intron retention between exon 13 and exon 14 with expected higher PSI values from the reduced splice site strength. Moreover, the PSI values were positively correlated with the expression levels of GRIA2-205, whose expression is significantly lower in AD compared to controls (Figure 5C). Thus, this editing site causing the retention of an intron in the GRIA2-205 transcript would affect its expression levels to have an anti-disease effect on AD. Additionally, previous studies reported the functions of this editing event in mutually exclusive splicing of exon 14 and exon15 in GRIA2, which enhanced the rate of channel desensitization and recovery from it, to influence excitatory synaptic transmission eventually [3,7]. All these results manifested that RNA editing events could alter the splicing patterns and have an opportunity to affect the AD-related biological processes in the brain.

From these analyses, two noteworthy editing events in GRIA2 nearly occurred in all the aspects from the specific editing identification, disease stage correlation, differential expression analysis, protein recoding influences, to alternative splicing studies. The evidence could be concluded to a hypothesis shown in Figure 5D, explaining the potential functions of these two editing events to AD from various sides. In sum, it shows the importance of A-to-I RNA editing research for understanding the AD mechanism and studying editing-related therapeutic targets.

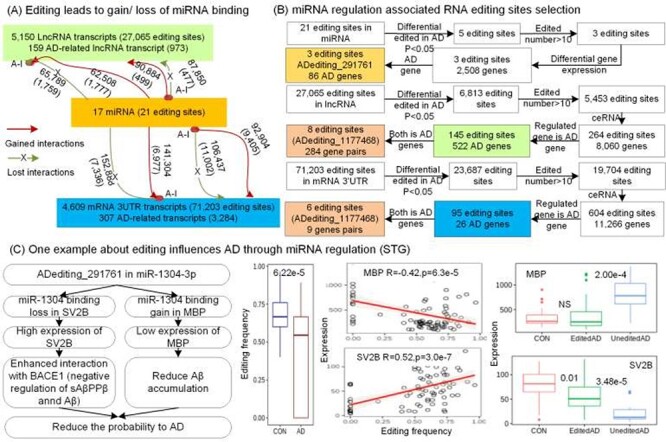

RNA editing events influence the expression of AD-related genes by altering miRNA regulation

RNA editing events in the binding sites of miRNAs or their seed regions can significantly alter the miRNA-RNA interactions, and then influence the regulations of downstream gene expressions. Through the miRNA target prediction, we identified 95 318 editing sites in 9776 transcripts, which were presumed to potentially create 387 600 new miRNA targets and eliminate 412 694 original ones (Figure 6A). Then we investigated the expressions of ceRNAs influenced by these altered miRNA-targets interactions, using the pipeline in Figure 6B. Eventually, there were 860 specific RNA editing events which might change the expressions of 20 109 genes through the altered miRNA regulation, including 596 AD-related genes (Table S8).

Figure 6 .

The influence of RNA editing events on miRNA regulation. (A) Overall statistics of the RNA editing events that modified miRNA binding across different gene types. The altered interactions are shown beside the arrows, and AD-related interactions are shown within brackets. (B) Pipeline for finding the altered miRNA regulation across the RNA editing sites in mRNAs, miRNAs and lncRNAs. (C) RNA editing event in miR-1304-3p might affect AD progression.

For example, an RNA editing event in chr11: 93733708 (ADediting_291761) of miR-1304-3p (Figure 6C) altered the miRNA binding target from original SV2B to MBP. Due to the lost regulation of miR-1304-3p, SV2B was upregulated in the RNA-edited samples. On the other hand, MBP was downregulated because of the gained interactions with miR-1304-3p. Since SV2B is known as interacting with BACE1 to negatively regulate the Aβ [47], and a previous study reported that the absence of MBP promotes neuroinflammation and reduces amyloid β-protein accumulation in Tg-5xFAD mice [48], this editing potentially alleviate AD condition, which was also supported by the significantly lower editing frequency of ADediting_291761 in AD than control as 0.46 < 0.68 in the STG region.

Another example is an RNA editing site in chr5: 143225281 (ADediting_1177468) of ARHGAP26-218 lncRNA transcript and ARHGAP26-201/222 mRNA 3’ UTR transcripts, which would lead to the loss of original binding targets of miR-490-3p, miR-3689a-3p, miR-6779-5p and miR-6780a-5p (Figure S6). The lost regulation of miRNAs seems to cause the increased expression of ARHGAP26 and indirectly lead to the reduced expression of CSF1 and BACE1-AS, due to their competing relationships. Several recent studies reported the functions of these three genes, such as the overexpression of ARHGAP26 could counteract the ability of Pyk2 to suppress dendritic spine density [49], the inhibition of CSF1R activating signaling (CSF1) resulted in improved performance in memory and behavioral tasks and prevention of synaptic degeneration [50] and BACE1-AS upregulated BACE1 mRNA stability for the production of the toxic Aβ [17]. Furthermore, the expression tendencies of these three genes in AD compared to control are also consistent with these functional descriptions (Figure S6). Therefore, ADediting_1177468 might improve AD condition, which also holds for the significantly lower editing frequency in AD than control as 0.69 < 0.78 in the PCC region. These examples may explain the potential influences of RNA editing on AD pathology by altering the miRNA regulation.

Discussion

This work represents a comprehensive and quantitative account of studies assessing A-to-I RNA editing from multi-scale aspects, in order to explain the potential roles or consequences of RNA editing on AD. To our knowledge, this is the first study, which conducted a systemic and deep annotation for individual A-to-I RNA editing events in AD based on a collective dataset of 1524 transcriptomes in multiple brain regions from three representative AD cohorts.

Considering all kinds of analysis results above, we identified 108 010 aberrant A-to-I RNA editing events with the potential promotion of AD occurrence or progression (Table S9) in total. One example is ADediting_461090 in SERPINA3 that occurred in the late AD stages only and significantly induced the higher expression of this gene to be involved in age-at-onset and disease duration of AD [36]. Additionally, there are other 66 editing events showing AD-specific frequencies and causing or increasing the abnormal expressions of AD-related genes simultaneously. Among them, 14 editing events in MICAL3, WAC, SUGT1 and PFKP were also positively associated with the disease stages in the CER region. These events are possibly involved in AD though dysfunctional MICAL-mediated actin disassembly [51], defective mTORC1 activity regulated by WAC [52], abnormal ubiquitin ligase activity required of SUGT1 [53] and excessive glycolysis activity associated with PFKP [54]. All these editing events might be capable to act as the pathologic biomarkers of AD.

Another set of 26 168 RNA editing events (Table S9) may play important roles in normal brain development and their deficiencies might induce synapse loss, Aβ accumulation and some other functions related to AD, like ADediting_1112942, ADediting_454734 and ADediting_291761 studied thoroughly in the above. Except for them, there are also 179 editing events showing control-specific frequencies and reversing the aberrant expressions of AD-related genes both. Among them, 67 editing events in ARHGAP26, CNTNAP2, ERBB4, FGF14, FRMPD4, KCNQ5, MAP2, NRG1 and NRXN3 were also negatively associated with the disease stages. These editing events may inhibit the interactions with Aβ [55] and promote the process necessary for brain development, such as dendritic spine density [49,56,57], cell–cell interactions [58], synapse function [39,59], excitability control [60] and neuritis outgrowth regulation [61] in the nervous system. The upregulating of these editing events might act as a therapeutic approach for AD.

Interestingly, 5582 editing events got our attention for their brain region-specific influences to AD (Table S9), like ADediting_1112899 of GRIA2 in the CER and PG regions mentioned before. Other examples include ADediting_1177468 of NRXN3 in the PCC and TCX regions, ADediting_1273861 (chr6: 7265702) of KCNQ5 in the STG and PG regions, and ADediting_403895 (chr13:66539967) of PCDH9 in the CER and IFG regions. The high frequency of these editing events might play a pathologic role to AD in one brain region, and be correlated with improved AD condition in a different brain region simultaneously. Therefore, we suggest considering the influence of different brain regions and, more importantly, paying attention to the potential negative effects of the proposed brain region-specific editing-related therapeutic methods for AD.

Our study performed a multi-scale functional analysis on RNA editing events in nine brain regions of AD patients and controls. On the other hand, there was a recent study showed that RNA editing alterations in a multi-ethnic Alzheimer disease cohort converged on immune and endocytic molecular pathways from studying the transcriptome of whole blood [4]. After overlapping the RNA editing events from whole blood in that recent study and that from brain regions in our study, we identified four common RNA editing events (Table S10). One editing site (hg19-chr17:8129592. hg38-chr17:8226274) in 3’ UTR of CTC1 (CST telomere replication complex component 1) has shown to disrupt miRNA binding sites, leading to the creation of the hsa-miR-1324 binding sites and the elimination of the hsa-miR-4305 binding sites supported by both of Targetscan and miRanda. Other three editing sites located in the coding regions of CDK10 (cyclin dependent kinase 10, hg19-chr16:89754057, hg38-chr16: 89687649), ACBD4 (acyl-CoA binding domain containing 4, hg19-chr17: 43219954, hg38-chr17: 45142587) and TTC38 (tetratricopeptide repeat domain 38, hg19, chr22:46688132. hg38, chr22:46292235) were predicted to change the protein sequences and following protein functions by ANNOVAR. From multiple analyses in our study, we also identified that the editing site in TTC38 showed differential editing frequencies (P = 5.14e-3), and positive correlations with AD stages (P = 5.73e-4 and R = 0.33) in the CER region, as differentially edited in blood samples. Interestingly, this gene was identified as one of the peripheral blood mononuclear cells-derived genes in the rheumatoid arthritis [62], which is an autoimmune disorder and also reported as one of the genes that have a correlation with age [63]. Furthermore, performing the functional enrichment analysis, we identified the editing events in our study which were enriched in some AD-related immune process (Table S5, Figure 3) as the involved biological processes including immune regulation, inflammation and endocytosis discovered by Gardner et al. [4]. For example, the MAPK signaling pathway, responsible for regulating the production of Th1-and Th2-type responses, is targeted by trypanosomatids to modulate the host’s immune response in order to favor parasite replication and survival [64], and cAMP is a negative regulator of T-cell activation [65]. Combined with the editing events from blood samples, our study may present the contributions of editing events in AD-related dysfunctional neuronal development and immune regulation.

During our analyses, we also studied the correlations between editing frequencies and ADAR expressions (P < 0.05 and |R |> 0.3), since the ADAR enzymes are mainly responsible for the deamination of adenosine (A) to inosine (I). Then we identified 127 965 ADAR-related editing events, including 12 700 editing events in AD-related genes (Table S11). As shown in the table, there were bidirectional relationships such as the editing deficiency and hyperactivity both in ADAR downregulated/upregulated samples. This phenomenon may need to be explained further to understand the potential mechanisms regulating the RNA editing frequency. From the previous studies, we noticed that RNA editing may be regulated by ADAR enzyme, RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) [66], splicing efficiency [67], SNPs [68] and unknown factors together.

The multi-scale analyses above mainly paid an attention on the transcript effects and did not cover the influences of RNA editing events on protein expressions, since the proteomics data from ROSMAP, MayoRNAseq and MSBB used different protocols and one brain region was not available for the proteomics. However, the importance of this analysis promoted us to perform a protein expression association study on the RNA editing events in coding regions for MSBB. Then we discovered that ADediting_1112899 of GRIA2 was associated with the protein expressions similarly to gene expressions as shown in Figure S7. This result revealed one of the functional roles of RNA editing events in not only transcript level, but also protein phenotypes.

Additionally, we also performed a differential editing frequency analysis across diverse apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele carriers (P < 0.05), since the ε4 allele of APOE is the best well-known genetic risk factor for AD [69]. Then we identified 8522 editing sites showing the differential editing frequencies (Table S12). For example, APOE ε4 allele was significantly associated with the upregulation of the editing frequency of ADediting_198978 (chr10_60045235_-) in ANK3 (Figure S8). Since ADediting_198978 had a positive correlation with ANK3 expressions (Table S4) and the expression of ANK3 is higher in the AD brain than in non-demented age-matched healthy control subjects as shown in the previous work [70] and also in our data (Figure S8), we hypothesized that APOE ε4 may increase editing frequency of ADediting_198978 and upregulate ANK3 expression to influence the risk of AD. From this investigation, we noticed that the genetic variations, such as APOE ε4 allele, could potentially affect the frequency of AD-specific editing events or alter RNA editing patterns to have an effect on AD. Our study will be necessary to analyze the downstream effects of genetic variations through A-to-I RNA editing events.

Furthermore, our presented work intended to study the individual editing site separately and its potential functions on the downstream expressions, alternative splicing, miRNA regulation or even the disease development. However, we also cared about the possible interactions of these editing events and their potential downstream co-effects. To study the possible associations of RNA editing events, we predicted MFE for transcript unedited, with one editing site and with all the possible editing sites. From the results shown in Table S13, we could notice that there are differences in MFEs between transcripts edited once and that edited in multiple positions, and the changes of MFEs are not exactly the times of editing sites. We also investigated the contributions of different editing sites on the gene expressions of one example gene with a regression model in Figure S9. It discussed the different contributions of 119 individual editing sites to the expression levels of NRXN3 in the PG brain region. This model might provide proof of the potential interaction effects of different editing events and their influences on the downstream gene expressions. Further, this model can be extended to include alternative splicing event, miRNA regulation etc. The individual effect of editing site studied in our presented study will be a basis for the further research on the interactions of multiple editing sites and their downstream co-effects.

Overall, our study provides unique resource, ADeditome, for the potential A-to-I RNA editing-related AD mechanisms. The potential influences of these editing events on AD pathogenesis may give us and other RNA editing or AD research consortiums the chances to look over the potential A-to-I RNA editing events to identify novel therapeutic targets. In the near future, we will continue to study the effects of RNA editing events on protein levels, investigate the RNA editing effects of genetic variations with machine learning and statistical methods, and propose a model to analyze the associations of multiple editing events and their influences on downstream co-effects.

Key Points

Editing frequency analysis let us know AD/control-specific RNA editing sites in 7687 genes and RNA editing candidates in 3114 genes related to AD progression.

Differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis between RNA-edited and non-edited samples across nine brain regions and pathway enrichment analysis of this help understand the potential AD-related functions and involved AD-related pathways of these RNA editing events in 1418 genes.

The influence of editing on amino acid sequences and possible damaging protein functions provide important editing candidates in 212 genes, including 47 AD-related genes.

Splice site strength prediction and comparison of PSI values between RNA-edited and non-edited samples give us the knowledge on the alternative splicing changes caused by editing sites in 73 genes, including six AD-related genes.

Studying the gain/loss of miRNA binding sites due to editing sites in 3’ UTR of mRNA, lncRNA and miRNA seed regions and following differential expression analysis of genes caused by altered miRNA regulation provide the potential influence of RNA editing on 20 109 genes, including 596 AD-related genes, through competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) relationships.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank the members of the Center for Computational Systems Medicine (CCSM) for valuable discussion.

Sijia Wu received her Ph.D. degree in Engineering from Xi'an Jiaotonng University, China, in 2018. She is currently working at the School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi'an, China. Her research interests are bioinformatics, computational biology and computational cancer genomics.

Mengyuan Yang is Ph.D. candidate in Bioinformatics in Tongji University, China. Her research interests are bioinformatics, computational biology and computational cancer genomics.

Pora Kim received her Ph.D. degree in Bioinformatics from Ewha Womans University, Korea, in 2013. Her research interests are bioinformatics, computational biology and computational cancer genomics.

Xiaobo Zhou received his Ph.D. degree in Applied Mathematics from Beijing University, China, in 1998. His research interests are bioinformatics, systems biology, imaging informatics and clinical informatics.

Contributor Information

Sijia Wu, School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi'an, China.

Mengyuan Yang, Tongji University, China.

Pora Kim, Ewha Womans University, Korea.

Xiaobo Zhou, Beijing University, China.

Data availability

The data involved in the study is available at https://ccsm.uth.edu/ADeditome.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01GM123037, U01AR069395-01A1, R01CA241930 to X.Z]; The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. Funding for open access charge: Dr & Mrs Carl V. Vartian Chair Professorship Funds to Dr. Zhou from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Nishikura K. A-to-I editing of coding and non-coding RNAs by ADARs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016;17(2):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg E, Levanon EY. A-to-I RNA editing—immune protector and transcriptome diversifier. Nat Rev Genet 2018;19(8):473–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behm M, Öhman M. RNA editing: a contributor to neuronal dynamics in the mammalian brain. Trends Genet 2016;32(3):165–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner OK, Wang L, Van Booven D, et al. RNA editing alterations in a multi-ethnic Alzheimer disease cohort converge on immune and endocytic molecular pathways. Hum Mol Genet 2019;28(18):3053–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khermesh K, D'Erchia AM, Barak M, et al. Reduced levels of protein recoding by A-to-I RNA editing in Alzheimer's disease. RNA 2016;22(2):290–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konen LM, Wright AL, Royle GA, et al. A new mouse line with reduced GluA2 Q/R site RNA editing exhibits loss of dendritic spines, hippocampal CA1-neuron loss, learning and memory impairments and NMDA receptor-independent seizure vulnerability. Mol Brain 2020;13(1):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomeli H, Mosbacher J, Melcher T, et al. Control of kinetic properties of AMPA receptor channels by nuclear RNA editing. Science 1994;266(5191):1709–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Jager PL, Ma Y, McCabe C, et al. A multi-omic atlas of the human frontal cortex for aging and Alzheimer’s disease research. Scientific data 2018;5:180142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen M, Carrasquillo MM, Funk C, et al. Human whole genome genotype and transcriptome data for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Scientific data 2016;3:160089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Beckmann ND, Roussos P, et al. The Mount Sinai cohort of large-scale genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic data in Alzheimer's disease. Scientific data 2018;5:180185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodes RJ, Buckholtz N. Accelerating Medicines Partnership: Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) Knowledge Portal Aids Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery through Open Data Sharing. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 2016;20(4):389–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013;29(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giudice CL, Tangaro MA, Pesole G, et al. Investigating RNA editing in deep transcriptome datasets with REDItools and REDIportal. Nat Protoc 2020;15(3):1098–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kai W, Mingyao L, Hakon H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38(16):e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Zu Siederdissen CH, et al. ViennaRNA package 2.0. Algorithms Mol Biol 2011;6(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schellenberg GD. International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Disease Project (IGAP) genome-wide association study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2012;4(8):P101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo Q, Chen Y. Long noncoding RNAs and Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Interv Aging 2016;11:867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flores J, Noël A, Foveau B, et al. Caspase-1 inhibition alleviates cognitive impairment and neuropathology in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Nat Commun 2018;9(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Liu W, McPhie DL, et al. APP-BP1 mediates APP-induced apoptosis and DNA synthesis and is increased in Alzheimer's disease brain. J Cell Biol 2003;163(1):27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao J, Cheng F, Jia P, et al. An integrative functional genomics framework for effective identification of novel regulatory variants in genome–phenome studies. Genome Med 2018;10(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rojek KO, Krzemień J, Doleżyczek H, et al. Amot and Yap1 regulate neuronal dendritic tree complexity and locomotor coordination in mice. PLoS Biol 2019;17(5):e3000253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang M, Qin L, Tang B. MicroRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Genet 2019;10:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC bioinformatics 2011;12(1):323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(W1):W90–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sim N-L, Kumar P, Hu J, et al. SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40(W1):W452–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010;7(4):248–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi Y, Chan AP. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics 2015;31(16):2745–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahles A, Ong CS, Zhong Y, et al. SplAdder: identification, quantification and testing of alternative splicing events from RNA-Seq data. Bioinformatics 2016;32(12):1840–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeo G, Burge CB. Maximum entropy modeling of short sequence motifs with applications to RNA splicing signals. J Comput Biol 2004;11(2–3):377–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam J-W, et al. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 2015;4:e05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betel D, Koppal A, Agius P, et al. Comprehensive modeling of microRNA targets predicts functional non-conserved and non-canonical sites. Genome Biol 2010;11(8):R90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chigaev M, Yu H, Samuels D, et al. Genomic positional dissection of RNA Editomes in tumor and normal samples. Front Genet 2019;10:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anantharaman A, Tripathi V, Khan A, et al. ADAR2 regulates RNA stability by modifying access of decay-promoting RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45(7):4189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sergi D, Campbell FM, Grant C, et al. SerpinA3N is a novel hypothalamic gene upregulated by a high-fat diet and leptin in mice. Genes Nutr 2018;13(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sardi F, Fassina L, Venturini L, et al. Alzheimer's disease, autoimmunity and inflammation. The good, the bad and the ugly. Autoimmun Rev 2011;11(2):149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamboh MI, Minster RL, Kenney M, et al. Alpha-1-antichymotrypsin (ACT or SERPINA3) polymorphism may affect age-at-onset and disease duration of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2006;27(10):1435–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salpietro V, Dixon CL, Guo H, et al. AMPA receptor GluA2 subunit defects are a cause of neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat Commun 2019;10(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cantanelli P, Sperduti S, Ciavardelli D, et al. Age-dependent modifications of AMPA receptor subunit expression levels and related cognitive effects in 3xTg-AD mice. Front Aging Neurosci 2014;6:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng J-J, Li W-X, Liu J-Q, et al. Low expression of aging-related NRXN3 is associated with Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018;97(28):e11343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright AL. The role of AMPA receptor GluA2 subunit Q/R site RNA editing in the normal and Alzheimer's diseased brain. Faculty of Medicine, St Vincent Clinical School, 2014. http://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/fapi/datastream/unsworks:12885/SOURCE02?view=true. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benarroch EE. Glutamatergic synaptic plasticity and dysfunction in Alzheimer disease: emerging mechanisms. Neurology 2018;91(3):125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vitolo OV, Sant'Angelo A, Costanzo V, et al. Amyloid β-peptide inhibition of the PKA/CREB pathway and long-term potentiation: reversibility by drugs that enhance cAMP signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2002;99(20):13217–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popugaeva E, Pchitskaya E, Bezprozvanny I. Dysregulation of intracellular calcium Signaling in Alzheimer's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018;29(12):1176–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hofer NT, Tuluc P, Ortner NJ, et al. Biophysical classification of a CACNA1D de novo mutation as a high-risk mutation for a severe neurodevelopmental disorder. Mol Autism 2020;11(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou H, Cheng Z, Bass N, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies glutamate ionotropic receptor GRIA4 as a risk gene for comorbid nicotine dependence and major depression. Transl Psychiatry 2018;8(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaisler-Salomon I, Kravitz E, Feiler Y, et al. Hippocampus-specific deficiency in RNA editing of GluA2 in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2014;35(8):1785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyamoto M, Kuzuya A, Noda Y, et al. Synaptic vesicle protein 2B negatively regulates the Amyloidogenic processing of AβPP as a novel interaction partner of BACE1. J Alzheimers Dis 2020;75(1):173–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ou-Yang M-H, Van Nostrand WE. The absence of myelin basic protein promotes neuroinflammation and reduces amyloid β-protein accumulation in Tg-5xFAD mice. J Neuroinflammation 2013;10(1):901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee S, Salazar SV, Cox TO, et al. Pyk2 signaling through Graf1 and RhoA GTPase is required for amyloid-β oligomer-triggered synapse loss. J Neurosci 2019;39(10):1910–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olmos-Alonso A, Schetters ST, Sri S, et al. Pharmacological targeting of CSF1R inhibits microglial proliferation and prevents the progression of Alzheimer’s-like pathology. Brain 2016;139(3):891–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alto LT, Terman JR. MICALs. Curr Biol 2018;28(9):R538–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.David-Morrison G, Xu Z, Rui Y-N, et al. WAC regulates mTOR activity by acting as an adaptor for the TTT and Pontin/Reptin complexes. Dev Cell 2016;36(2):139–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spiechowicz M, Bernstein H-G, Dobrowolny H, et al. Density of Sgt1-immunopositive neurons is decreased in the cerebral cortex of Alzheimer's disease brain. Neurochem Int 2006;49(5):487–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hipkiss AR. Aging, Alzheimer’s disease and dysfunctional glycolysis; similar effects of too much and too little. Aging Dis 2019;10(6):1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang H, Zhang L, Zhou D, et al. Ablating ErbB4 in PV neurons attenuates synaptic and cognitive deficits in an animal model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis 2017;106:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piard J, Hu J-H, Campeau PM, et al. FRMPD4 mutations cause X-linked intellectual disability and disrupt dendritic spine morphogenesis. Hum Mol Genet 2018;27(4):589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim Y-J, Yoo J-Y, Kim O-S, et al. Neuregulin 1 regulates amyloid precursor protein cell surface expression and non-amyloidogenic processing. J Pharmacol Sci 2018;137(2):146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodenas-Cuadrado P, Ho J, Vernes SC. Shining a light on CNTNAP2: complex functions to complex disorders. Eur J Hum Genet 2014;22(2):171–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Di Re J, Wadsworth PA, Laezza F. Intracellular fibroblast growth factor 14: emerging risk factor for brain disorders. Front Cell Neurosci 2017;11:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mayordomo-Cava J, Yajeya J, Navarro-Lopez JD, et al. Amyloid-β (25-35) modulates the expression of GirK and KCNQ channel genes in the hippocampus. PLoS One 2015;10(7):e0134385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang J, Dong X-P. Dysfunction of microtubule-associated proteins of MAP2/tau family in prion disease. Prion 2012;6(4):334–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang H, Guo J, Jiang J, et al. New genes associated with rheumatoid arthritis identified by gene expression profiling. Int J Immunogenet 2017;44(3):107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harries LW, Hernandez D, Henley W, et al. Human aging is characterized by focused changes in gene expression and deregulation of alternative splicing. Aging Cell 2011;10(5):868–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yan K, Gao LN, Cui YL, et al. The cyclic AMP signaling pathway: exploring targets for successful drug discovery. Mol Med Rep 2016;13(5):3715–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Athari SS. Targeting cell signaling in allergic asthma. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2019;4(1):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brümmer A, Yang Y, Chan TW, et al. Structure-mediated modulation of mRNA abundance by A-to-I editing. Nat Commun 2017;8(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Licht K, Kapoor U, Amman F, et al. A high resolution A-to-I editing map in the mouse identifies editing events controlled by pre-mRNA splicing. Genome Res 2019;29(9):1453–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Breen MS, Dobbyn A, Li Q, et al. Global landscape and genetic regulation of RNA editing in cortical samples from individuals with schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci 2019;22(9):1402–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 2009;63(3):287–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Santuccione A, Merlini M, Shetty A, et al. Active vaccination with ankyrin G reduces β-amyloid pathology in APP transgenic mice. Mol Psychiatry 2013;18(3):358–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data involved in the study is available at https://ccsm.uth.edu/ADeditome.