Abstract

Solar photovoltaic (PV) energy is one of the most widely used renewable energy options around the world. However, its electrical efficiency drops with increasing PV module temperature, it is therefore necessary to find appropriate ways to improve the performance of the module under high temperature conditions. In this study we evaluated the impact of simultaneous dual surface cooling on the PV module's output performance experimentally. The PV module's rear surface was cooled using cotton wick mesh which absorbs water from a perforated pipe and use capillary action to transfer the water down the surface of the rear side of the module. The perforated pipe is strategically positioned at the upper part of the panel and as a result, water from the tank through the holes in the pipe also spread on the front surface of the panel. The experiment recorded a temperature drop of 23.55 °C. This resulted in about 30.3% improvement in the output power of the panel. The cooled PV module also recorded an average efficiency of 14.36% against 12.83% for the uncooled panel. This represent a difference of 1.53% which is 11.9% improvement in the electrical efficiency of the cooled panel. In effect, the proposed approach had a significant positive effect on the energy yield of the PV system.

Keywords: Photovoltaic panel cooling, Thermal management, Efficiency improvement, Phase change materials, Cotton wick

Photovoltaic panel cooling; Thermal management; Efficiency improvement; Phase change materials; Cotton wick.

1. Introduction

The use of alternative energy to meet electricity and heating demand is increasing around the world, particularly in countries where those resources exist. This has become more necessary as a result of the negative effect of greenhouse gases on the environment due to the continuous use of fossil fuel to meet energy demand globally [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Solar photovoltaic (PV) power is one of the clean technologies that is widely used around the world, it is probably the most common technology [7, 8, 9]. A solar PV panel is made up of an array of solar cells, these cells transform solar irradiance directly into streams of electrical charges. The continuous improvement of solar technologies in terms of its efficiency and cost has led to its increased use [10, 11]. Although solar technology is currently being used widely across the globe, it has some weaknesses such as decrease in efficiency with increasing operating temperature [12], low energy conversion, and the formation of dust on the module's surface which negatively affect the operations of the technology to reach its maximum working potential [13]. A rise in the temperature of a PV panel basically affect its operating parameters which ultimately reduce the output efficiency of the power plant [14]. It has been estimated that every 1 °C increase in the ambient temperature decreases the performance efficiency of the PV by 0.4–0.5% [13]. Another reason why the cooling of PV panels is important is that it increases the lifetime of the panel, i.e., it slows down the rate of degradation. According to Royo et al. [15], a PV's lifetime can be increased from the usual 25–30 years to about 48 years when specific cooling techniques are applied. Hence, researchers are studying different modern ways to reduce the operating temperature of the panels using different cooling techniques.

A number of researchers have adopted different techniques in the cooling of solar PV panels, this include active and passive methods. Hernández et al. [16] used forced air stream to enhance the PV module's output performance. According to their study, the PV panel's temperature reduced by 15 °C leading to an increase in the electric energy yield of 15%. Chavan and Devaprakasam [17] used phase change material (PCM) (i.e. a white petroleum jelly) to boost the performance of a solar PV thermal system. Their results suggest that the PVT-PCM panel had a temperature reduction of 8.10% compared to the conventional panel. The water-based PVT-PCM system also recorded a power which is 4.06% more than that of the conventional PV panel. Nada et al. [18] experimentally studied the effect of nano materials mixed with PCMs on the thermal characteristics of PV modules. The authors indicated that the integration of PV with PCM and nano-particles could enhance the efficiency of the system by 13.2%. Krauter [19] suggested in his study that, flowing of a cooling water film on the cell's surface decreases its temperature substantially and as a result its efficiency can be enhanced by approximately 10%.

In other studies, Elnozahy et al. [20] empirically assessed the performance of self-cooled and cleaned PV module in hot arid areas. According to their results, the efficiency of the PV with self-cooled and cleaned system was 11.7% whiles that of the PV system without coolant and cleaning system was 9%. Abdolzadeh and Ameri [21] examined the effect of spray cooling on the front of solar panels and found a 48% enhancement in the power of the system when the temperature of the decreased from 58 °C to 37 °C. Baloch et al. [22] numerically and experimentally analyzed a converging channel heat exchanger for the cooling of a PV system. According to their results, the cell temperature for the uncooled PV was 71.2 °C in June and 48.3 °C for the month of December. However, the application of the converging cooling technique reduced the temperatures to 45.1 °C and 36.4 °C for the months of June and December, respectively. Bahaidarah et al. [23] conducted a study on the rear surface cooling of PV module under hot weather conditions of the Middle East. Their study suggest that the active cooling of the back surface of the panel resulted in a drop of its temperature by about 20% which led to 11% increase in its efficiency.

Grubisic-Cabo [24] empirically investigated a passive cooled free-standing PV module integrated with fixed aluminum fins at the rear surface. They assessed two fin positions and geometrics to know their general performance response and suitability. The initial fin geometry involved a series of fins arranged in a top-down direction. Perforated and randomly positioned aluminum fins which is the second option was found to be more appropriate in terms of performance. According to their study, the proposed modification led to a 2% increase in the average efficiency of the PV module. Idoko et al. [25] employed surface water cooling and aluminum heat sink attached to the back of PV modules to reduce the temperature to 20 °C. Their cooling mechanism was able to increase the efficiency of the module by at least 3%. Deokar et al. [26] actively cooled a PV module using M.S chips and thermal grease. According to their study, their approach of cooling the PV resulted in a temperature reduction of 16.1 °C leading to an improvement of 12.3% in the electrical efficiency of the module.

Chandrasekar et al. [27] also examined the use of wicks at the rear side of the PV module to increase heat transfer and the rate of cooling in a cost-effective manner. Their results indicate that the PV panel without cooling had a temperature of 65 °C, it however reduced to 45 °C when the cooling wick with water was added. Hussein et al. [28] indicated in their study that an active cooling of PV panel reduced the PV temperature from 78 °C to 70 °C which increased the electrical efficiency of the PV module by 9.8%. Indartono et al. [29] proposed a PV/T system which used petroleum jelly as PCM for the cooling of the PV module. The temperature of the PV panel with the PCM reduced compared to the reference panel without the PCM. Whereas the electrical efficiency of the PV-PCM was about 21.2%, that of the referenced panel without the PCM was about 7.3%. Abdo et al. [30] cooled a PV module by means of saturated activated alumina with saline water. They used six diverse water salinities, this includes (0, 5, 10, 35, 80, and 337) particles per thousands under varying intensities of solar radiation. They also suggested new external and internal configuration for the containers of the materials. Their proposed approach led to a 3–4 °C enhancement in the cooling effect of the module. Abdallah et al. [31] proposed the use of saturated zeolite with water as a cooling material for PV modules. Their study indicated a significant temperature reduction for the cooled panel, this was about 9 °C and 14.9 °C for radiation intensities of 1000 and 600 W/m2, respectively. The temperature reduction led to enhancement of the electrical efficiencies by 10% and 7% for radiation intensities of 600 and 1000 W/m2, respectively. Aberoumand et al. [32] conducted an experimental analysis on PV/T system with energy and exergy assessment via stable Ag/Water nanofluids. According to their study, the use of the nanofluids significantly improved the exergy and energy efficiency of the hybrid PV/T systems. The exergy for the system was found to be 50% higher than the uncooled PV module.

Furthermore, Nizetic et al. [33] employed a novel technique using several containers filled PCM materials mounted at the rear side of the panel for cooling. Results from their study indicated that the system with several independently filled PCM containers had a performance improvement of 10.7%. Singh et al. [34] experimentally investigated the performance of a PV module which is integrated with PCM and several conductivity-enhancing containers. The outcome of their study show that their proposed heat sink was able to reduce the PV module's temperature from 64.4 °C to 46.4 °C for the month of January and 77.1 °C–53.8 °C in June. The module's electrical efficiency during noon also increased from 9.5% to 10.5%. Similarly, Rajvikram et al. [35] used PV-PCM with aluminum sheet fixed at the rear side of the panel to enhance the efficiency of the module. The average conversion efficiency of the modified module was identified to be 24.4%. A 2% increase in the electrical efficiency was recorded due to a 10.35 °C reduction in temperature. Abdollahi, and Rahimi [36] proposed a new passive cooling approach that works with a naturally circulating water. A PCM-based cooling system was used to remove the heat from the cooling water. They obtained the highest increase in generated power relative to the reference case in the presence of nano-composed oil, these are 48.23, 46.63, and 44.74% at solar radiation intensities of 690, 530 and 410 W/m2, respectively. The potential to use palm wax to regulate the temperature of PV system was investigated by [37]. They used a finned PCM enclosure to effect the cooling of the PV module. Their study was able to enhance the performance ratio and module efficiency by 4.8% and 5.3%, respectively.

From the various literature reviewed supra, it is clear that a number of studies have been done which are all aimed at minimizing the temperature of the PV panel using different mechanisms. This study is also conducted to enhance these literatures further by adopting strategies that cool the PV system at both the rear and front surface simultaneously. The study used cotton wick mesh and water to cool the rear surface of the panel using capillary action techniques, where the cotton wick absorbs water from perforated pipes and spread it down the rear surface of the panel. One issue that this study minimizes is the loss of water through evaporation through the covering of the back surface of the panel with aluminum sheet which is also strategically perforated to allow the flow of air into the inner section of the enclosed area. This approach does not totally prevent the loss of water but minimizes its loss especially at the rear section of the panel. This is very important because water is not abundant in every part of this world and so appropriate mechanisms have to be instituted to minimize the loss of water for reuse by the system. This cooling process is also very simple to construct and less bulky compared to some of the approaches reviewed supra. This study is also unique in the sense that, it requires only a single polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe to spread the water both on the front surface and the rear surface, this cuts down cost considerably unlike other similar studies that used multiple pipes fixed at the back of the panel.

The paper has been organized as follows, section 2 presents a brief discussion on the effect of temperature on the PV modules performance, the materials and method used for the study are presented in section 3, section 4 presents the results and discussion, whiles the conclusion is presented in section 5.

2. The impact of temperature on PV cell's efficiency

As indicated earlier, the output performance of PV cell decreases with increasing temperature, mainly because of increase in the rate of internal carrier recombination, which is triggered by increased carrier concentrations. The cells operating temperature has a crucial role in the conversion process of the photovoltaic. The power output and electrical efficiency of the PV module relates linearly with the operating temperature (OT) [38]. A temperature above the 25 °C OT of a panel results in a reduction in the band gap of the semi-conductor material in the solar cell leading to a reduction in the open circuit voltage [39]. The correlations which shows the temperature of a PV cell as a function of weather variables such as solar radiation , local wind speed , and ambient temperature are presented below. Eq. (1) shows the effect of temperature on the PV cell's electrical efficiency [12, 38].

| (1) |

where the denotes the fill factor, the open circuit voltage is denoted by , signifies the short circuit current, and the maximum power point in the module's I–V curve is denoted by the subscript .

Both fill factor and open circuit voltage substantially decrease with increase in temperature (this is because the electrical properties of the semi-conductor begin to be dominated by the thermally excited electrons), whereas there is an increase in the short circuit current, but only slightly [12, 40]. The net effect therefore results in a linear relation as indicated in Eq. (2).

| (2) |

where the electrical efficiency of the module at the reference temperature is denoted by and at a solar radiation flux of 1000 W/m2. The solar radiation coefficient and the temperature coefficient are principally material properties with values approximately 0.12 and 0.004 K−1, respectively, for crystalline silicon modules [41]. Taking that of the solar radiation coefficient as zero yields Eq. (3) which is the traditional linear relation for electrical efficiency of a PV system [12].

| (3) |

The manufacturer usually give the values of and . They can however be found from flash tests, in this case, for a given solar radiation flux, the electrical output of the module is measured at two different temperatures. The temperature coefficient's actual value depends not on the PV material alone but on the as well [10]. It is given by the ratio as indicated in Eq. (4).

| (4) |

where the high temperature at which the electrical efficiency of the module drops to zero is denoted by [42]. This temperature is 270 °C for crystalline silicon solar cells. The module/cell temperature that is not readily obtainable can be replaced by the , which is the nominal operating cell temperature. The expression for it is indicated in Eq. (5) [12].

| (5) |

The effect of wind on the temperature of the cell is suggested by Skoplaki et al. [43] as indicated in Eq. (6).

| (6) |

where temperature coefficient and efficiency of the maximal power under standard test conditions (STC) are denoted by and , respectively. represent the in-plane irradiance, the absorption coefficient for the cells is represented by , the transmittance of the cover system is also denoted by and the wind convection coefficient (WCC) is denoted by which is normally a linear function of the wind speed . represent the WCC for wind speed under NOCT conditions, i.e., .

3. Materials and methodology

The description of the materials and experimental setup for the study are presented in this section. The setup for the experiment was designed with water loss minimization in mind. The experiment was conducted in June 2021 during the summer period in Yekaterinburg in Russia at the Ural Federal University.

3.1. Experimental setup and components

The experimental setup consists of a cooled panel using a cotton wick mesh fixed at the rear side of the panel and cooled with water using capillary action. A 16 mm PVC pipe tube was connected to a source of water in a tank at a height higher than the PV panel. This is to enable the free flow of water using gravity without needing to use extra energy to pump the water to the module, a pump is however required to pump the water back into the storage tank. The PVC pipe was perforated with a 1 mm driller tooth severally along its length in order to allow the water to flow along the pipe into the cotton mesh and onto the front surface of the panel simultaneously. A portion of the cotton mesh which extends down the rare side of the PV panel is wrapped around the pipe at the upper part of the PV panel so that it can absorb water from the perforated holes.

A total of 14 K-type thermocouples with temperature range -200 °C–1370 °C and a resolution of 0.1 °C were used to measure the temperatures of the two PV panels with the help of SD logger 88598. Each of the two panels had 7 K-type thermocouples strategically positioned at the back, this is to enable as find the average temperature of the panel. They were attached to the rear side of each of the panels as shown in Figure 1a before the cotton mesh was laid over them as shown in Figure 1b. The thermocouples and the cotton mesh were held tightly to the rear surface of the panel using universal sealant moment silicone gel (white). In order to solve one major problem associated with the evaporative cooling method as indicated in [44], an aluminum metal sheet was attached to the back of the cooled PV panel. This metal sheet with ridges was selected in order to enable the creation of holes on the crest section of the sheet. The essence of these holes on the metal sheet is to enhance the flow of air into the enclosed area, this is as shown in Figure 1c. The galvanized sheet captures the evaporating water and returns it to the basin that is fixed beneath the PV panel, which is latter recycled into the water tank to be reused. The GM 1362-EN-01 temperature thermometer with temperature range of -30 °C–70 °C was also used to measure the ambient temperature. The solar irradiation was measured with the Tenmars TM-207 pyranometer, it has a typical accuracy of ±10 W/m2 and an additional temperature induced error of ±0.38 W/m2. The clamp meter used to measure the current and voltage has uncertainty that range from ±1.5–2.0%.

Figure 1.

PV panel with (a) installed K-type thermocouples (b) installed cotton mesh (c) rear side of the cooled panel with aluminum sheet and perforated holes.

The two panels used for the experiment have capacities of 30 W each with dimensions 95 × 45 cm. A thermal imager known as Testo 875 camera is used to record infra-red thermal images for both panels during mid-day when temperatures were very high. These images are to act as additional information for the results obtained in the experiment.

3.2. Experimental procedure

The panels were placed on adjustable stand and were positioned at a tilt angle of 45o towards the southern section of the country in order to receive the maximum total solar radiation as shown in Figure 2. The temperature, voltage and current of both panels were measured during the day at regular interval. A digital clamp multimeter was used to take the readings of the voltage and current for each panel, these two parameters were then used to find the power output of the two modules.

Figure 2.

(a) Experimental setup (b) Schematic diagram of the experiment.

3.3. Experimental uncertainty assessment

In any experimental works, there is the potential to encounter some level of errors that may arise from the measurand or the measurements [45]. In mathematics if there are number of observations and denotes any of the observations (where can have any integer value beginning from 1 to ), the mean which in this case is denoted by can be calculated using Eq. (7).

| (7) |

In experimental works, it is important to quantitatively assess how much each measurement scatter about the mean. The level of scatter about the mean value helps in identifying the level of precision of the experimental results, and as a result assist in the quantification of the random uncertainty. The standard deviation (SD) is the most accepted quantitative measure of scatter. The SD can be calculated using Eq. (8) for cases which have data points with equal weight [46].

| (8) |

The SD provides the estimate for the random uncertainty for any one of the values used in calculating the SD. The SD of the mean value for a number of measurements with equal statistical weights can be calculated using Eq. (9), the is the uncertainty [46].

| (9) |

4. Results and discussion

This section present two analysis, i.e., the thermal characteristics of the PV panels and the electrical output performance.

4.1. Thermal characteristics of the panel and weather conditions

The solar radiation and the ambient temperature was recorded from 10:00 am to 4:00 pm within a 30-minute interval and the results are presented in Figure 3. As can be seen from the figure, the solar radiation for the day was at its peak around 11:30 am, mostly this should have been around 12 pm but around that time, there was some little cloud formation which may have affected the solar irradiation around mid-day. The day recorded an average solar irradiation of 1002 W/m2. The average ambient temperature for the day is also around 28.28 °C with the highest temperature of about 32 °C occurring at about 1:30 pm.

Figure 3.

Weather characteristics.

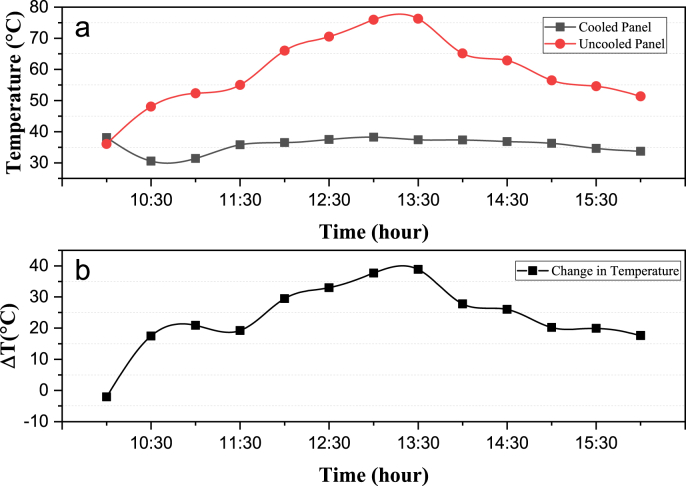

The temperature for the two panels were obtained by finding the average of the temperatures recorded by each of the seven thermocouples installed at the rear side of the two panels for each 30 min interval. The results for the temperature distribution for the period within which the experiment was conducted is as shown in Figure 4. It can be observed from the figure that the temperature of the uncooled panel reached its peak between 1:00 pm and 1:30 pm. This can be attributed to the high ambient temperature recorded between that period of the experiment as indicated in Figure 3. The cooled panel was however able to maintain some level of stability relative to its temperature due to the effectiveness of the cooling mechanism. The temperatures of both panels however started reducing after 1:30 pm due to a sharp drop in the ambient temperature occasioned by clouds formation which also affected the intensity of the solar radiation. According to the results the cooled system recorded an average temperature of 35.72 °C whiles the uncooled system recorded an average temperature of 59.27 °C. The difference in temperature between the two panels averagely is 23.55 °C. It can be observed from the figure that, the temperature of the cooled panel was slightly higher than the uncooled panel at the beginning of the experiment, obviously due to the fact that, the cooled panel was deficient of natural air at the rear side of the panel, because of both the cotton wick mesh and the aluminum sheet at its back. As a result, the uncooled panel was being cooled by the ambient air which at the start of the experiment was relatively colder. The SD for the uncooled panel was relatively high compared to the cooled system, the uncooled panel recorded 11.57 against 2.47 for the cooled system. Similarly, the uncertainty for the uncooled system was 3.21 against 0.69 for the cooled system. These large uncertainties can be associated with the sharp rise in the ambient temperature after mid-day and the subsequent drop in the ambient temperature after about 2:30 pm. This caused sharp rise in the panels temperature especially the uncooled panel, hence the high SD for the uncooled panel. However, the SD in the cooled panel was significantly consistent, this is obviously due to the positive effect of the cooling system on the PV panel. The generally accepted error in temperature measure is up to 10%. In other cooling mechanisms such as Mittelman et al. [47] who employed passive air cooling for rooftop integrated photovoltaics, the researchers obtained a temperature difference of 17.6 °C. Haidar et al. [44] using an evaporative cooling method at the rear side of the panel obtained a temperature reduction of 20 °C for the cooled PV panel. Elbreki et al. [48] proposed a passive cooling technique for PV systems using planner reflector and lapping fins. Their results showed that the PV system with 18 lapping fins and 27.7 mm fin pitch had an efficiency improvement of 11.2% compared to the bare PV with 9.81% at 1000 W/m2. Furthermore, Lucas et al. [49] also assessed experimentally the electrical and thermal performance of a PV module cooled with evaporative chimney, their module recorded an 8 K temperature difference. Dida et al. [50] obtained a temperature reduction of 20 °C (26%) through evaporative cooling. Comparing the results from this study to the reviewed literatures shows that, the proposed approach in this study in cooling the PV system is effective and is capable to reduce considerably the temperature of the PV system to enhance its performance.

Figure 4.

(a) Temperature of both panels (b) change in temperature between both panels.

Around 11:30 am, the temperature of the two panels were assessed using the thermal imager camera, the results for both panels are as indicated in Figure 5. The use of the thermal imager camera is fast and contactless, which enables users to access the temperature of a facility even under operation conditions. It is generally advisable to conduct such assessment under sunny weather conditions with sun irradiance of at least 600 W/m2 [10]. The temperature of the panel is visualized to show the distribution of the temperature across the surface of the panel. According to the results from the thermal imager, the temperature distribution does not vary significantly from the results obtained from the thermocouples. The average temperature for the uncooled panel using the thermal imager is 51.9 °C compared to the 53 °C recorded using the thermocouples during the same period. In the case of the cooled panel the average temperature recorded using the thermal imager is 37.8 °C compared to 35.78 °C recorded using the thermocouples. These differences could be because the thermocouples are closer in terms of contact than the thermal imager and therefore can record more accurately than the thermal imager, also, time differences, i.e., the figures for that of the thermocouples and the thermal imager were not simultaneously recorded. Therefore, time differences could cause the temperature to either increase or decrease slightly based on the ambient temperature at the time. It can be observed from the thermal image for the cooled panel that, the temperature distribution for the panel is relatively uniform obviously due to the cotton wick that was placed uniformly behind the panel with uniform water absorption. The values on the y-axis in the histogram denote the percentage of temperature distribution on the surface of the panel. This indicate that the temperature of the panel is not equal at every section, certain parts of the module are hotter than others.

Figure 5.

Temperature distribution histogram and thermal images for the (a) uncooled panel (b) cooled panel.

4.2. Effect on the electrical characteristics of the panel

The electrical characteristics of the panels, i.e., the cooled and uncooled were assessed in terms of their voltage (V) and current (I). In this case, the output power and efficiency (η) for the two modules were computed using Eqs. (10) and (11), respectively [30, 44, 51].

| (10) |

| (11) |

Where the actual temperature of the panel is denoted by , the efficiency of the panel at the reference temperature is denoted by , in this study the reference temperature is taken as 25 °C. The temperature coefficient used for this study is taken as 0.004 [52] and is represented by .

Solar panel's I–V characteristics depends on the and the . Similarly, the and the also depend on the temperature of the panel and incident solar irradiance on the panel. The is inversely proportional to the module's temperature and as a result, it negatively affect the output power with increase in the module's temperature, and thus, decreases the output power, whiles the increases slightly. The results for the output current recorded for both panels are presented in Figure 6a. As can be seen from the figure, at the start of the experimental process, the uncooled panel had a current that is relatively higher than the cooled panel, this is a because, as indicated in the temperature distribution figure in Figure 4 the temperature of the cooled panel is relatively higher than the uncooled panel, the reason for this has been discussed supra. However, when the cooling process started, it was noticed that the current of the cooled panel averagely increased slightly more than the uncooled panel. The average current generated by the cooled panel during the entire experimental process is about 0.70 A, whiles the uncooled panel generated an average of 0.60 A, a difference of 0.10 A, which represent some 14.3% increment as a result of the cooling process. As expected, the current increased with increasing temperature, although slightly. The highest current of 0.80 A was recorded between 11:30 am and 12:00 pm when the solar irradiation was highest and ambient temperature relatively lower.

Figure 6.

The (a) current and (b) voltage characteristics of the two panels.

In the case of the voltage, the results are presented in Figure 6b. Similarly, it is observed that, the voltage of the cooled panel was higher than the uncooled panel, obviously because of the higher temperature of the uncooled panel. According to the obtained figures, the cooled panel recorded an average voltage of 18.53 V as against 16.71 V recorded by the uncooled panel. This translates into a difference of 1.82 V, representing 10.89% improvement in voltage of the cooled panel. These results show the positive effect the cooling mechanism proposed in this study had on the performance of the panel. The improvement in the voltage for the cooled panel is certainly expected to positively affect the efficiency of the panel.

The comparison of the output power for the two PV modules is presented in Figure 7. The power of the uncooled module at the beginning of the test was relatively higher than the cooled panel. It however changed in favor of the cooled panel as the temperature of the uncooled panel increased. Power production from the cooled panel remained higher throughout the day. The maximum output power of 15.04 W was recorded around 11:30 am when the highest solar irradiation was recorded during the experiment for the cooled PV panel, whiles the uncooled panel recorded 11.60 W during that same period. This is about 29.66% improvement in the energy yield as a result of the implementation of the cooling approach proposed in this study. The average power for the entire experimental period for the cooled panel is 13.03 W compared to 10.00 W for the uncooled PV panel. It can be said that the 23.55 °C reduction of the temperature as presented earlier in this research led to an overall increment of 30.3% in the output power.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the power output for the two modules.

The influence of the cooling process on the PV panel's efficiency and improvement in efficiency are presented in Figure 8. It is clear from the figure that, the cooling process in this study had a significant impact on the efficiency of the cooled power plant. According to results from the experiment, the cooled PV module recorded an average efficiency of 14.36% against 12.83% for the uncooled panel. This represent a difference of 1.53% which is 11.9% improvement in the efficiency of the cooled panel. It is seen that the efficiency of the panel decreased with increasing temperature. It decreased sharply after mid-day when the temperature of the panel was highest. The effect of the cooling process is seen most after mid-day, it can be seen that the efficiency of the cooled panel remained relatively constant when the high temperature periods. The negative improvement recorded at the beginning of the experiment indicate that, the uncooled panel was more efficient at that time of the experiment. This is because, the uncooled panel was relatively colder than the cooled panel at the beginning of the experiment. There was however a sharp improvement in the efficiency of the cooled panel when the cooling process began. This is an indication that the used approach in cooling the PV is effective. Previous works such as Abdallah et al. [31] obtained electrical efficiency improvement of 6.5–7% using a combination of activated alumina, pure water and circular perforation for the cooling. Elbreki et al. [48] obtained an electrical efficiency of 10.68% using passive cooling, i.e. fins and planar reflector to cool PV panels. Chandrasekar et al. [27] used cotton wicks and water to cool solar PV, according to their results, the maximum module efficiency is 10.4%. Sun et al. [53] employed the optics based approach: selective-spectral and radiative cooling to manage the temperature of a PV module. They obtained an efficiency increment of 0.5–1.8%. Similarly, Hasan et al. [54] obtained 1.3% increase the PV module's electrical conversion efficiency. Lucas et al. [49] assessed the viability of photovoltaic evaporative chimney as an alternative way to enhance solar cooling. According to their results, the electrical efficiency of the PV system could improve averagely from 4.9%-7.9% during mid-day under Mediterranean summer weather conditions. Finally, Dida et al. [50] used the passive cooling approach to manage the temperature of PV systems under hot climatic conditions. They also obtained improvement in the electrical efficiency of the panel which ranges from 9–14.75%. Comparing the results of this study to the previous studies presented supra indicate that, the proposed approach in this study has the potential to enhance the output performance of a PV panel. The improvement in the efficiency of the module in this study either falls above the efficiencies recorded by previous studies or falls within the range recorded by such studies.

Figure 8.

(a) Efficiency for both panels (b) improvement in panel efficiency.

5. Conclusion

Solar energy is among the most widely used alternative clean energies globally. In as much as it is a clean source of energy generation, it also comes with some disadvantages which impedes its output performance. Factors such as the temperature of the module and the incidence solar radiation play a key role in the efficiency of the PV panel. This study therefore combined both front and rear surface cooling to manage the temperature of the PV module. A cotton wick mesh was used to absorb and spread the water through capillary action at the rear side of the panel. In order to partially solve one major issue associated with evaporative cooling, i.e., water loss through evaporation, an aluminum sheet was fixed at the back of the panel to collect the escaping vapor back into a basing. Holes were created in the aluminum sheet in order to allow some level of air exchange in the inner section of the panel and the ambient air. According to the results the cooled system recorded an average temperature of 35.72 °C as whiles the uncooled system recorded an average temperature of 59.27 °C. The reduction in temperature is averagely 23.55 °C. The cooled panel recorded an average voltage of 18.53 V as against 16.71 V recorded by the uncooled panel. This translates into a difference of 1.82 V, representing 10.89% improvement in the cooled panel's voltage, the change in the current is however, only 0.1 A which is expected since current does not significantly change under increasing temperature.

The average power for the entire experimental period for the cooled panel is 13.03 W compared to 10.00 W for the uncooled PV panel. It can be said that the 23.55 °C reduction of the temperature as presented earlier in this research led to an overall improvement of 30.3% in the output power of the module. Similarly, the cooled PV module recorded an average efficiency of 14.36% against 12.83% for the uncooled panel. This represent a difference of 1.53% which is 11.9% improvement in the efficiency of the cooled panel.

In effect, the experimental procedure used to manage the temperature of the PV panel has proved to be effective and can be used especially in areas of high temperatures around the world to cool PV systems. One challenge that was encountered during the experiment was the blocking of the holes we created on the pipe tube around which the cotton wick mesh was wrapped to absorb the water and also spread the water on the front surface of the panel by filth. This happened because, the basin that collected the water had no sieves to filter out dirt and as a result, they were pumped back into the water storage tank which later choked the tiny holes, preventing the smooth flow of water onto the surface of the panel. This can be resolved by fixing a sieve on the top of the basing or its outlet to filter out such dirt. The diameter of 1 mm for the holes we created in the pipe can also be increased to prevent choking. Despite the detailed nature of this study, we did not consider the effect of flow rate on the performance of the module, it is therefore recommended as part of future studies to assess the effect of flow rate on the output performance. This is important because it will help to know the flow rate at which the efficiency of the PV cell becomes virtually constant.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ephraim Bonah Agyekum: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Seepana PraveenKumar: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Naseer T. Alwan, Vladimir Ivanovich Velkin, Sergey E. Shcheklein: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Agyekum E.B., Velkin V.I. Optimization and techno-economic assessment of concentrated solar power (CSP) in South-Western Africa: a case study on Ghana. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2020;40:100763. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agyekum E.B., Amjad F., Mohsin M., Ansah M.N.S. A bird’s eye view of Ghana’s renewable energy sector environment: a Multi-Criteria Decision-Making approach. Util. Pol. 2021;70:101219. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agyekum E.B., PraveenKumar S., Eliseev A., Velkin V.I. Design and construction of a novel simple and low-cost test bench point-absorber wave energy converter emulator system. Inventions. 2021;6:20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agyekum E.B., Adebayo T.S., Bekun F.V., Kumar N.M., Panjwani M.K. Effect of two different heat transfer fluids on the performance of solar tower CSP by comparing recompression supercritical CO2 and rankine power cycles, China. Energies. 2021;14:3426. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adebayo T.S., Agboola M.O., Rjoub H., Adeshola I., Agyekum E.B., Kumar N.M. Linking economic growth, urbanization, and environmental degradation in China: what is the role of hydroelectricity consumption? Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18:6975. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adebayo T.S., Awosusi A.A., Oladipupo S.D., Agyekum E.B., Jayakumar A., Kumar N.M. Dominance of fossil fuels in Japan’s national energy mix and implications for environmental sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18:7347. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homadi A., Hall T., Whitman L. Study a novel hybrid system for cooling solar panels and generate power. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020;179:115503. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alwan N.T., Shcheklein S.E., Ali O.M. Experimental investigation of modified solar still integrated with solar collector. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2020;19:100614. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alwan N.T., Shcheklein S.E., Ali O.M. Experimental analysis of thermal performance for flat plate solar water collector in the climate conditions of Yekaterinburg, Russia. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021;42:2076–2083. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad F.F., Ghenai C., Hamid A.K., Rejeb O., Bettayeb M. Performance enhancement and infra-red (IR) thermography of solar photovoltaic panel using back cooling from the waste air of building centralized air conditioning system. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021;24:100840. [Google Scholar]

- 11.EmmanuelP Agbo, CollinsO Edet, ThomasO Magu, ArmstrongO Njok, ChrisM Ekpo, Louis H. Solar energy: a panacea for the electricity generation crisis in Nigeria. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skoplaki E., Palyvos J.A. On the temperature dependence of photovoltaic module electrical performance: a review of efficiency/power correlations. Sol. Energy. 2009;83:614–624. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sudhakar P., Santosh R., Asthalakshmi B., Kumaresan G., Velraj R. Performance augmentation of solar photovoltaic panel through PCM integrated natural water circulation cooling technique. Renew. Energy. 2021;172:1433–1448. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sudhakar P., Kumaresan G., Velraj R. Experimental analysis of solar photovoltaic unit integrated with free cool thermal energy storage system. Sol. Energy. 2017;158:837–844. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royo P., Ferreira V.J., López-Sabirón A.M., Ferreira G. Hybrid diagnosis to characterise the energy and environmental enhancement of photovoltaic modules using smart materials. Energy. 2016;101:174–189. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazón-Hernández R., García-Cascales J.R., Vera-García F., Káiser A.S., Zamora B. Improving the electrical parameters of a photovoltaic panel by means of an induced or forced air stream. Int. J. Photoenergy. 2013;2013:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chavan S.V., Devaprakasam D. Improving the performance of solar photovoltaic thermal system using phase change material. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nada S.A., El-Nagar D.H., Hussein H.M.S. Improving the thermal regulation and efficiency enhancement of PCM-Integrated PV modules using nano particles. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018;166:735–743. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krauter S. Increased electrical yield via water flow over the front of photovoltaic panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cell. 2004;82:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elnozahy A., Rahman A.K.A., Ali A.H.H., Abdel-Salam M., Ookawara S. Performance of a PV module integrated with standalone building in hot arid areas as enhanced by surface cooling and cleaning. Energy Build. 2015;88:100–109. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdolzadeh M., Ameri M. Improving the effectiveness of a photovoltaic water pumping system by spraying water over the front of photovoltaic cells. Renew. Energy. 2009;34:91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baloch A.A.B., Bahaidarah H.M.S., Gandhidasan P., Al-Sulaiman F.A. Experimental and numerical performance analysis of a converging channel heat exchanger for PV cooling. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015;103:14–27. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bahaidarah H., Subhan A., Gandhidasan P., Rehman S. Performance evaluation of a PV (photovoltaic) module by back surface water cooling for hot climatic conditions. Energy. 2013;59:445–453. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grubišić-Čabo F., Nižetić S., Čoko D., Marinić Kragić I., Papadopoulos A. Experimental investigation of the passive cooled free-standing photovoltaic panel with fixed aluminum fins on the backside surface. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;176:119–129. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Idoko L., Anaya-Lara O., McDonald A. Enhancing PV modules efficiency and power output using multi-concept cooling technique. Energy Rep. 2018;4:357–369. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deokar V.H., Bindu R.S., Potdar S.S. Active cooling system for efficiency improvement of PV panel and utilization of waste-recovered heat for hygienic drying of onion flakes. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021;32:2088–2102. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandrasekar M., Suresh S., Senthilkumar T., Ganesh karthikeyan M. Passive cooling of standalone flat PV module with cotton wick structures. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013;71:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussien H.A., Numan A.H., Abdulmunem A.R. Improving of the photovoltaic/thermal system performance using water cooling technique. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015;78 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Indartono Y.S., Suwono A., Pratama F.Y. Improving photovoltaics performance by using yellow petroleum jelly as phase change material. Int. J. Low Carbon Technol. 2016;11:333–337. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdo S., Saidani-Scott H., Borges B., Abdelrahman M.A. Cooling solar panels using saturated activated alumina with saline water: experimental study. Sol. Energy. 2020;208:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdallah S.R., Saidani-Scott H., Benedi J. Experimental study for thermal regulation of photovoltaic panels using saturated zeolite with water. Sol. Energy. 2019;188:464–474. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aberoumand S., Ghamari S., Shabani B. Energy and exergy analysis of a photovoltaic thermal (PV/T) system using nanofluids: an experimental study. Sol. Energy. 2018;165:167–177. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nižetić S., Jurčević M., Čoko D., Arıcı M. A novel and effective passive cooling strategy for photovoltaic panel. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021;145:111164. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh P., Mudgal V., Khanna S., Mallick T.K., Reddy K.S. Experimental investigation of solar photovoltaic panel integrated with phase change material and multiple conductivity-enhancing-containers. Energy. 2020;205:118047. [Google Scholar]

- 35.R M., L S., R S., A H., D A. Experimental investigation on the abasement of operating temperature in solar photovoltaic panel using PCM and aluminium. Sol. Energy. 2019;188:327–338. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdollahi N., Rahimi M. Potential of water natural circulation coupled with nano-enhanced PCM for PV module cooling. Renew. Energy. 2020;147:302–309. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wongwuttanasatian T., Sarikarin T., Suksri A. Performance enhancement of a photovoltaic module by passive cooling using phase change material in a finned container heat sink. Sol. Energy. 2020;195:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubey S., Sarvaiya J.N., Seshadri B. Temperature dependent photovoltaic (PV) efficiency and its effect on PV production in the world – a review. Energy Procedia. 2013;33:311–321. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan M.S., Hegde V., Shankar G. 2017 International Conference on Current Trends in Computer, Electrical, Electronics and Communication. CTCEEC); 2017. Effect of temperature on performance of solar panels- analysis; pp. 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dincer F., Meral M.E. Critical factors that affecting efficiency of solar cells. SGRE. 2010;1:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Notton G., Cristofari C., Mattei M., Poggi P. Modelling of a double-glass photovoltaic module using finite differences. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2005;25:2854–2877. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garg H.P., Agarwal R.K. Some aspects of a PV/T collector/forced circulation flat plate solar water heater with solar cells. Energy Convers. Manag. 1995;36:87–99. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skoplaki E., Boudouvis A.G., Palyvos J.A. A simple correlation for the operating temperature of photovoltaic modules of arbitrary mounting. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cell. 2008;92:1393–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haidar Z.A., Orfi J., Kaneesamkandi Z. Experimental investigation of evaporative cooling for enhancing photovoltaic panels efficiency. Results Phys. 2018;11:690–697. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chandrika V.S., Karthick A., Kumar N.M., Kumar P.M., Stalin B., Ravichandran M. Experimental analysis of solar concrete collector for residential buildings. Int. J. Green Energy. 2021;18:615–623. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pengra D., Dillman T. Notes on data analysis and experimental uncertainty. https://courses.washington.edu/phys431/uncertainty_notes.pdf (accessed June 27, 2021)

- 47.Mittelman G., Alshare A., Davidson J.H. A model and heat transfer correlation for rooftop integrated photovoltaics with a passive air cooling channel. Sol. Energy. 2009;83:1150–1160. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elbreki A.M., Sopian K., Fazlizan A., Ibrahim A. An innovative technique of passive cooling PV module using lapping fins and planner reflector. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2020;19:100607. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lucas M., Aguilar F.J., Ruiz J., Cutillas C.G., Kaiser A.S., Vicente P.G. Photovoltaic Evaporative Chimney as a new alternative to enhance solar cooling. Renew. Energy. 2017;111:26–37. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dida M., Boughali S., Bechki D., Bouguettaia H. Experimental investigation of a passive cooling system for photovoltaic modules efficiency improvement in hot and arid regions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021;243:114328. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agyekum E.B. Techno-economic comparative analysis of solar photovoltaic power systems with and without storage systems in three different climatic regions, Ghana. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021;43:100906. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dwivedi P., Sudhakar K., Soni A., Solomin E., Kirpichnikova I. Advanced cooling techniques of PV modules: a state of art. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2020;21:100674. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun X., Silverman T.J., Zhou Z., Khan M.R., Bermel P., Alam M.A. Optics-based approach to thermal management of photovoltaics: selective-spectral and radiative cooling. IEEE J. Photovoltaics. 2017;7:566–574. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hasan A., Alnoman H., Shah A.H. Energy efficiency enhancement of photovoltaics by phase change materials through thermal energy recovery. Energies. 2016;9:782. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.