Abstract

Urea cycle disorders (UCDs), inborn errors of hepatocyte metabolism, cause hyperammonemia and lead to neurocognitive deficits, coma, and even death. Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate (NaPB), a standard adjunctive therapy for UCDs, generates an alternative pathway of nitrogen deposition through glutamine consumption. Administration during or immediately after a meal is the approved usage of NaPB. However, we previously found that preprandial oral administration enhanced its potency in healthy adults and pediatric patients with intrahepatic cholestasis. The present study evaluated the effect of food on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of NaPB in five patients with UCDs. Following an overnight fast, NaPB was administered orally at 75 mg/kg/dose (high dose, HD) or 25 mg/kg/dose (low dose, LD) either 15 min before or immediately after breakfast. Each patient was treated with these four treatment regimens with NaPB. With either dose, pre-breakfast administration rather than post-breakfast administration significantly increased plasma PB levels and decreased plasma glutamine availability. Pre-breakfast LD administration resulted in a greater attenuation in plasma glutamine availability than post-breakfast HD administration. Plasma levels of branched-chain amino acids decreased to the same extent in all tested regimens. No severe adverse events occurred during this study. In conclusion, preprandial oral administration of NaPB maximized systemic exposure of PB and thereby its efficacy on glutamine consumption in patients with UCDs.

Keywords: Amino acids, Clinical study, Pharmacokinetics, Urea cycle disorders

Abbreviations: AAs, amino acids; AUC0–4, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to 4 h; BCAA, branched-chain amino acids; CI, confidence interval; Cmax, the maximum plasma concentration; HD, high dose; iAUC0–4, incremental area under the curve from time 0 to 4 h after breakfast; Kel, elimination rate constant; LD, low dose; NaPB, sodium 4-phenylbutyrate; PA, 4-phenylacetate; PAG, 4-phenylacetylglutamine; PB, 4-phenylbutyrate; PD, pharmacodynamics; PFIC, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis; PK, pharmacokinetics; SD, standard deviation; Tmax, time to reach Cmax; UCDs, urea cycle disorders.

1. Introduction

The urea cycle, a biochemical pathway that converts highly toxic ammonia to urea in mammals, eliminates waste nitrogen arising from the catabolism of dietary and endogenous proteins. A deficiency of one of six enzymes and two transporters involved in ureagenesis causes urea cycle disorders (UCDs), a group of inborn errors of urea synthesis and related metabolic pathways that results in multiorgan manifestations including systemic accumulation of ammonia to toxic levels [1]. Hyperammonemia can cause neurocognitive deficits that have a serious impact on a patient's intellectual ability and lead to coma and even death [2]. Therefore, treatment of UCDs must be prioritized to prevent hyperammonemia.

4-Phenylbutyrate (PB) is converted to 4-phenylacetate (PA) by β-oxidation and then to 4-phenylacetylglutamine (PAG) by conjugation of PA with glutamine, the major reservoir of nitrogen [3]. As a result, PB generates an alternative pathway of nitrogen deposition that replaces the urea cycle through urinary excretion of PAG and consequently reduces the systemic ammonia level in UCDs [4]. Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate (NaPB) therapy has been the standard adjunctive treatment for long-term management of UCDs for over 20 years. However, there is no clinical evidence for the approved regimen indicating whether NaPB should be taken with, or immediately after, a meal [5].

We have identified an interaction between NaPB and food in healthy adults [6] and in pediatric patients with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) [7], a rare inherited autosomal recessive liver disease [8], [9]. Pre-breakfast, rather than post-breakfast, oral administration markedly increased systemic exposure of PB and decreased plasma glutamine availability after breakfast in the healthy adults [6]. In the pediatric patients with PFIC, we found that food intake before oral administration of NaPB reduced plasma PB levels and diminished its therapeutic efficacy through a choleretic effect [7], another pharmacological action of NaPB [10], [11], [12]. Importantly, there were no severe adverse events attributable to preprandial oral administration of NaPB.

Patients with UCDs have difficulty taking NaPB because of its unpleasant odor and taste, high sodium content, high pill burden, and high economic cost, which results in poor medication compliance and hence worsens the therapeutic outcome [13]. We hypothesized that interactions with food may influence the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of NaPB, resulting in higher clinically effective doses of NaPB in patients with UCDs. To gain an insight into the optimal regimen of NaPB for treatment of UCDs, we evaluated the effect of meal timing on the PK and PD of NaPB in five patients with UCDs. The pharmacological action of NaPB was determined by measurement of plasma glutamine levels. Plasma levels of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) were monitored because of the increased risk of BCAA deficiency in patients with UCD undergoing NaPB treatment [14].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics statement

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Tokyo, Fujita Health University School of Medicine, and Juntendo University, and was performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (as revised in Edinburgh 2000). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrollment in the study. The study was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry at http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index.htm (UMIN000025627).

2.2. Patients

Five Japanese patients who had a confirmed diagnosis of UCDs and had been receiving a stable dose of NaPB (190–220 mg/kg/day) were enrolled. This patient group was aged 2 years to 23 years and comprised two ornithine transcarbamylase-deficient females, two carbamoylphosphate synthetase I-deficient females, and one citrullinemic (argininosuccinate synthetase-deficiency) female (Table 1). Liver transplant, hypersensitivity to drugs and additives, clinically significant laboratory abnormalities, or any condition that could affect ammonia levels were major exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Demographic data of UCD patients.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical presenation | |||||

| Age | 2y | 6y | 15y | 10y | 23y |

| Sex | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female |

| Dignosis | CPS1D | OTCD | OTCD | ASSD | CPS1D |

| Age of onset | 2d | 1y | 2y | 1y | 4d |

| Weight | 10.5 kg | 24 kg | 25 kg | 22.6 kg | 47 kg |

| Hight | 103 cm | 116 cm | 135 cm | 130 cm | 145 cm |

| Feeding | Mainly oral, Gastrostomy | Oral | Mainly gastrostomy, Oral | Oral | Oral |

| Deveolopment | Mild mental retardation | Normal | Bedridden | Normal | Intellectual and physical diability |

| Prescribed dietary intake | |||||

| Energy (% of RDA⁎) | 100 | 83 | 76 | 100 | 79 |

| Protein (% of RDA⁎) | 93 | 110 | 90 | 160 | 70 |

| Treatment | |||||

| Benzoate | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Arginine | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Citrurine | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Lactulose | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| EAA | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

2.3. Study design

To examine the effect of meals on the PK and amino acid (AA) availability of NaPB in patients with UCDs, a single-center, open-label, four-period, single-dose study of NaPB was conducted at the Fujita Health University School of Medicine. The four periods consisted of four treatment regimens: pre-breakfast oral administration of NaPB (Buphenyl; OrphanPacific, Tokyo, Japan) at 75 mg/kg/dose (high dose, HD); post-breakfast oral administration of NaPB at 75 mg/kg/dose (HD); pre-breakfast oral administration of NaPB at 25 mg/kg/dose (low dose, LD); and post-breakfast oral administration of NaPB at 25 mg/kg/dose (LD). HD is a common dose in current clinical usage when used three times a day, whereas LD is below the lower limit of the approved dose [5]. PK and PD were assessed by serial measurement of plasma PB and glutamine, respectively. Safety was assessed through plasma levels of BCAA as well as standard laboratory tests, physical examinations, and monitoring of adverse events including common signs and symptoms associated with UCDs or NaPB therapy.

Five eligible participants as described above were enrolled by the physicians in this study between December 2017 and August 2019. The patients fasted overnight and were given NaPB orally, either HD or LD, 15 min before breakfast or just (<10 min) after breakfast. They were each treated with the four treatment regimens with NaPB (Supplemental Fig. 1). All patients were given their typical diet to control dietary intake of protein and energy before and during this study (Table 1) and prohibited from ingesting any food for at least 4 h after NaPB administration. The diet therapy, mainly protein restriction, for each patient depended on developmental needs, age, body weight, and disease severity. The patients remained on their prescribed diet, which included identical amounts and types of protein and supplements, throughout the study. Treatment with other drugs was maintained during participation in the PK study (Table 1).

Blood samples were collected through a catheter placed in a forearm vein into an EDTA-2Na+-pretreated tube before dosing and at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, and 240 min after drug administration. Blood samples were placed at 4 °C immediately after collection and centrifuged for 15 min at 1700 ×g to prepare plasma. The prepared specimens were stored at −80 °C until assay.

2.4. Quantification of concentrations of PB and AAs in human plasma

Blood levels of PB and 9 AAs (glutamine, leucine, isoleucine, valine, threonine, methionine, histidine, phenylalanine, and lysine) were measured as described previously [6], [7].

2.5. Pharmacokinetic analysis

The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the time to reach Cmax (Tmax) of PB were determined directly from the observed data. The area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to 4 h after the administration of NaPB (AUC0–4) of PB was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. The elimination rate constant (Kel) of PB was estimated using least-squares regression analysis from the terminal post-distribution phase of the concentration–time curve.

The incremental area under the curve from time 0 to 4 h after breakfast (iAUC0–4) for each AA was defined as the change in plasma AA value from baseline and calculated for each subject using the linear trapezoidal rule.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data are shown as means ± standard deviation (SD), unless otherwise indicated. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (v. 6; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and Pingouin, a free statistics library of Python (v. 3.6). The differences between the treatment regimens in Cmax, AUC0–4, Tmax, and Kel of PB, and iAUC0–4 of AA were evaluated with one-way Welch analysis of variance and subsequent Games–Howell test considering unequal variances [15], [16].

3. Results

Five patients were enrolled, and four patients completed the defined protocol (Supplemental Fig. 1). The demographic characteristics of the patients are outlined in Table 1. One patient dropped out after completing two treatment regimens, pre-breakfast and post-breakfast oral administration of NaPB at HD, because of personal reasons. Her data were included in the analysis of PK of PB (Fig. 1) and plasma AAs (Fig. 2). No clinically undesirable signs or symptoms attributable to the administration of NaPB were detected during the study.

Fig. 1.

Effect of food on the systemic exposure of PB after oral administration of NaPB in patients with UCDs.

NaPB (75 mg/kg/dose (HD) or 25 mg/kg/dose (LD)) was given orally to patients with UCDs either 15 min before or just (<10 min) after breakfast following an overnight fast. Plasma concentrations of PB were determined at the times shown. Data are shown as means ± SD (HD, N = 5; LD, N = 4) of the plasma concentrations. BF, breakfast; HD, high dose; LD, low dose.

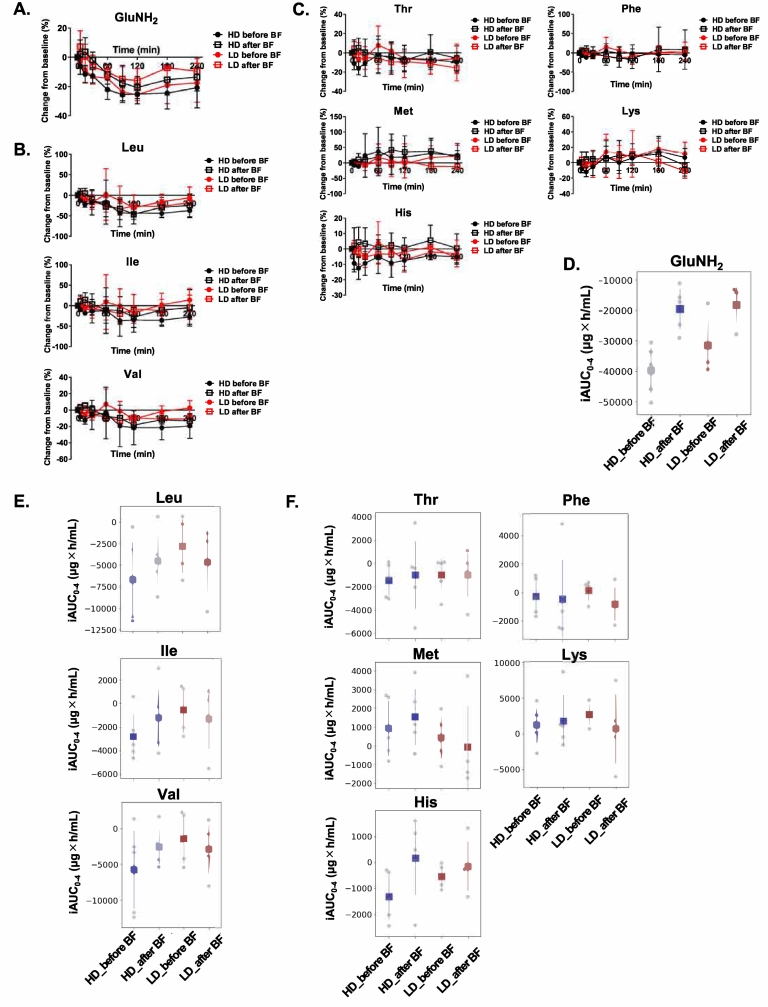

Fig. 2.

Effect of NaPB on AA availability after breakfast in patients with UCDs.

NaPB (75 mg/kg/dose (HD) or 25 mg/kg/dose (LD)) was given orally to patients with UCDs either 15 min before or just (<10 min) after breakfast following an overnight fast. (A–C) Change rate from the baseline of glutamine (A), BCAAs (B), and the other essential AAs (C) after breakfast. Plasma concentrations of each AA were determined at the times shown. Change rate from baseline (pre-breakfast concentration) is calculated for each AA and is shown as means ± SD (HD, N = 5; LD, N = 4). (D–F) Availability of glutamine (D), BCAAs (E), and the other essential AAs (F) after breakfast. iAUC0–4 of AAs was calculated as described in Materials and methods. Data are presented as means ± SD (HD, N = 5; LD, N = 4). BF, breakfast; GluNH2, glutamine; HD, high dose; His, histidine; Ile, isoleucine; LD, low dose; Leu, leucine; Lys, lysine; Met, methionine; Phe, phenylalanine; Thr, threonine; Val, valine.

3.1. PK of PB

The mean plasma concentration–time curves of PB after a single oral dose of NaPB for each regimen were plotted (Fig. 1) and used to calculate the PK parameters of PB (Table 2 and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). At both HD and LD, although more prominent at LD, post-breakfast administration markedly reduced the plasma concentration of PB. The Cmax values of PB for post-breakfast administration were lower than those for pre-breakfast administration by 2.26 times (P = 0.028) at HD and 3.45 times (P = 0.009) at LD, respectively. For both doses, breakfast timing affected the Tmax and Kel of PB. The Tmax of PB after post-breakfast administration was later than that after pre-breakfast administration. Breakfast intake before administration of NaPB significantly decreased the Kel of PB by 2.19 times (P = 0.001) at HD and 2.50 times (P = 0.001) at LD, respectively.

Table 2.

Plasma PK parameters of PB in UCD patients administered with NaPB.

| Dose |

HD |

LD |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usage | Before BF | After BF | Before BF | After BF |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 160.1 | 73.4 | 93.2 | 27.3 |

| [114.4–205.8] | [54.3–92.6] | [64.4–121.9] | [20.5–34.1] | |

| Tmax (h) | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 1.25 |

| [0.25–1.00] | [0.5–2.0] | [0.25–0.25] | [0.25–2.0] | |

| AUC0–4 (μg×h/mL) | 183.1 | 126.9 | 66.7 | 32.9 |

| [121.0–245.1] | [77.0–176.7] | [38.0–95.3] | [20.0–45.7] | |

| Kel (/h) | 0.0298 | 0.0136 | 0.0420 | 0.0168 |

| [0.0265–0.0332] | [0.0111–0.0162] | [0.0368–0.0472] | [0.0117–0.0220] | |

Data are shown as mean (95% confidence interval); Tmax data are shown as median (range). BF, breakfast.

3.2. Effect of NaPB on plasma AAs

Fig. 2A to C shows the mean values of changes in plasma glutamine, BCAA, and the other essential AAs, respectively, at each time point after breakfast for the four treatment regimens of NaPB. To evaluate the effect of NaPB on AA intake from breakfast, an iAUC value during the period after breakfast to lunch (iAUC0–4) was calculated for glutamine, BCAA, and the other essential AAs (Fig. 2D to F and Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

NaPB attenuated the iAUC0–4 of glutamine at both HD and LD, and its effect was more pronounced in the pre-breakfast than post-breakfast regimens (Fig. 2D). The iAUC0–4 of glutamine for pre-breakfast administration of NaPB was lower than that for post-breakfast administration of NaPB by 2.03 times (P = 0.001) at HD and 1.73 times (P = 0.15) at LD. Pre-breakfast LD administration had a greater effect on the iAUC0–4 of glutamine than post-breakfast HD administration (Fig. 2D). NaPB reduced the iAUC0–4 of BCAA, but food and NaPB dose had no evident effect on its value (Fig. 2E). There was no significant difference in the iAUC0–4 of the other essential AAs among the NaPB regimens (Fig. 2F).

4. Discussion

NaPB has been established as standard adjunctive therapy for long-term management of UCDs [17]. Administration during or immediately after a meal is the approved usage of NaPB. However, the optimal regimen for NaPB therapy has never been fully examined in UCDs. This study examined the impact of the timing of food intake on PK and PD of PB after a single oral administration of NaPB in five patients with UCDs at two doses, 75 mg/kg/dose, a common dose in current clinical usage when used three times a day, and 25 mg/kg/dose, a dose below the lower limit of approved labeling [5]. For both doses, breakfast intake before NaPB administration markedly reduced the systemic exposure to PB and thereby its potency to sequester plasma glutamine (Fig. 1, Fig. 2D). Compared with post-breakfast HD administration, pre-breakfast LD administration of NaPB significantly attenuated the iAUC0–4 of glutamine. The food effect was not observed in safety measures including BCAA deficiency, a possible cause of several adverse events in UCD patients undergoing NaPB therapy [18], [19], [20] (Fig. 2E). These findings are consistent with our previous study to evaluate PK, efficacy, and safety of NaPB in 20 healthy adults and seven pediatric patients with intrahepatic cholestasis [6], [7].

It has been suggested that, after intestinal absorption, PB is mainly taken up by hepatocytes and converted to PA through β-oxidation [21], [22]. PA forms PAG through conjugation with glutamine and is then excreted into the urine [23]. The longer time until Tmax observed with post-breakfast administration of NaPB (Table 2) suggests that the reduction in PB systemic exposure as a result of food intake is attributable to inhibition of the intestinal absorption of PB as well as the ionization of PB by changes in the gastric pH and/or protein binding. Understanding the molecular mechanisms responsible for the food effect on PK of PB will make it possible to gain greater insight into the PK/PD relationship of NaPB and prescribe NaPB based on genetic variability, drug–drug interactions, and drug–nutrient–food interactions [6].

Our study involved only a small number of participants. However, food effect on PK and efficacy to sequester glutamine were similar to the results in our previous study in healthy adults [6]. It is conceivable that the findings in this study apply to UCDs. Another limitation of this study was that the therapeutic efficacy and safety of NaPB was not assessed. The influence of meal timing on therapeutic efficacy and safety of NaPB should be examined in future clinical trials with more patients with UCDs than was possible in the current study.

In conclusion, we showed that food intake before the administration of NaPB markedly reduced systemic exposure to PB and its efficacy to sequester glutamine in patients with UCDs. The unpleasant odor and taste, high pill burden, and the high economic cost of NaPB prompt poor medication compliance and worsen the therapeutic outcome [13]. Therefore, if the food effect is confirmed in terms of therapeutic efficacy and safety of NaPB, preprandial administration may become the standard usage instead of the current approved prandial or postprandial administration, in patients who take NaPB orally.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Supplementary tables

Financial support

This work was supported by research grants from the Nakatomi Foundation to H.H. The authors confirm independence from the sponsors; the content of the article has not been influenced by the sponsors.

Author contributions

Y.N. and K.Y. designed and performed the clinical study and wrote the manuscript. S.O. measured plasma concentrations of PB, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. T.M. performed statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. S.N. S.H. and M.S. designed the clinical study and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Y.H. and Y.M. measured plasma concentrations of amino acids. H.K. reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. H.H. conceived, designed, and supervised the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript before submission.

Declaration of competing interest

Hisamitsu Hayashi consults for OrphanPacific. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families who participated in this study.

References

- 1.C. Members of the Urea Cycle Disorders. Batshaw M.L., Tuchman M., Summar M., Seminara J. A longitudinal study of urea cycle disorders. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014;113:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machado M.C., Pinheiro da Silva F. Hyperammonemia due to urea cycle disorders: a potentially fatal condition in the intensive care setting. J. Intens. Care. 2014;2:22. doi: 10.1186/2052-0492-2-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasumov T., Brunengraber L.L., Comte B., Puchowicz M.A., Jobbins K., Thomas K., David F., Kinman R., Wehrli S., Dahms W., Kerr D., Nissim I., Brunengraber H. New secondary metabolites of phenylbutyrate in humans and rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004;32:10–19. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brusilow S.W. Phenylacetylglutamine may replace urea as a vehicle for waste nitrogen excretion. Pediatr. Res. 1991;29:147–150. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.F.a.D.A. (FDA) 2009. Labels for NDA 020572: BUPHENYL® (Sodium Phenylbutyrate) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osaka S., Nakano S., Mizuno T., Hiraoka Y., Minowa K., Hirai S., Mizutani A., Sabu Y., Miura Y., Shimizu T., Kusuhara H., Suzuki M., Hayashi H. A randomized trial to examine the impact of food on pharmacokinetics of 4-phenylbutyrate and change in amino acid availability after a single oral administration of sodium 4-phenylbutyrarte in healthy volunteers. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2021;132:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakano S., Osaka S., Sabu Y., Minowa K., Hirai S., Kondou H., Kimura T., Azuma Y., Watanabe S., Inui A., Bessho K., Nakamura H., Kusano H., Nakazawa A., Tanikawa K., Kage M., Shimizu T., Kusuhara H., Zen Y., Suzuki M., Hayashi H. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy of 4-phenylbutyrate in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:17075. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53628-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morotti R.A., Suchy F.J., Magid M.S. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) type 1, 2, and 3: a review of the liver pathology findings. Semin. Liver Dis. 2011;31:3–10. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suchy F.J., Sundaram S., Shneider B. 13. Familial Hepatocellular Cholestasis Liver Disease in Children. 4th Edition. 2014. pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasegawa Y., Hayashi H., Naoi S., Kondou H., Bessho K., Igarashi K., Hanada K., Nakao K., Kimura T., Konishi A., Nagasaka H., Miyoshi Y., Ozono K., Kusuhara H. Intractable itch relieved by 4-phenylbutyrate therapy in patients with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 1. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2014;9:89. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi H., Sugiyama Y. 4-phenylbutyrate enhances the cell surface expression and the transport capacity of wild-type and mutated bile salt export pumps. Hepatology. 2007;45:1506–1516. doi: 10.1002/hep.21630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naoi S., Hayashi H., Inoue T., Tanikawa K., Igarashi K., Nagasaka H., Kage M., Takikawa H., Sugiyama Y., Inui A., Nagai T., Kusuhara H. Improved liver function and relieved pruritus after 4-phenylbutyrate therapy in a patient with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 2. J. Pediatr. 2014;164 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shchelochkov O.A., Dickinson K., Scharschmidt B.F., Lee B., Marino M., Le Mons C. Barriers to drug adherence in the treatment of urea cycle disorders: assessment of patient, caregiver and provider perspectives. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2016;8:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee B., Diaz G.A., Rhead W., Lichter-Konecki U., Feigenbaum A., Berry S.A., Le Mons C., Bartley J., Longo N., Nagamani S.C., Berquist W., Gallagher R.C., Harding C.O., McCandless S.E., Smith W., Schulze A., Marino M., Rowell R., Coakley D.F., Mokhtarani M., Scharschmidt B.F. Glutamine and hyperammonemic crises in patients with urea cycle disorders. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2016;117:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Games Paul A., Howell John F. Pairwise multiple comparison procedures with unequal N's and/or variances: a Monte Carlo Study. J. Educ. Stat. 1976;1:113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H. Department of Biostatistics Richmond, Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University; 2015. Comparing Welch's ANOVA, a Kruskal-Wallis Test and Traditional ANOVA in Case of Heterogeneity of Variance. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haberle J., Burlina A., Chakrapani A., Dixon M., Karall D., Lindner M., Mandel H., Martinelli D., Pintos-Morell G., Santer R., Skouma A., Servais A., Tal G., Rubio V., Huemer M., Dionisi-Vici C. Suggested guidelines for the diagnosis and management of urea cycle disorders: first revision. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019;42:1192–1230. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holecek M. Branched-chain amino acids in health and disease: metabolism, alterations in blood plasma, and as supplements. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 2018;15:33. doi: 10.1186/s12986-018-0271-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair K.S., Short K.R. Hormonal and signaling role of branched-chain amino acids. J. Nutr. 2005;135:1547S–1552S. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.6.1547S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watford M. Lowered concentrations of branched-chain amino acids result in impaired growth and neurological problems: insights from a branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex kinase-deficient mouse model. Nutr. Rev. 2007;65:167–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S.W., Hooker J.M., Otto N., Win K., Muench L., Shea C., Carter P., King P., Reid A.E., Volkow N.D., Fowler J.S. Whole-body pharmacokinetics of HDAC inhibitor drugs, butyric acid, valproic acid and 4-phenylbutyric acid measured with carbon-11 labeled analogs by PET. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2013;40:912–918. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGuire B.M., Zupanets I.A., Lowe M.E., Xiao X., Syplyviy V.A., Monteleone J., Gargosky S., Dickinson K., Martinez A., Mokhtarani M., Scharschmidt B.F. Pharmacology and safety of glycerol phenylbutyrate in healthy adults and adults with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2077–2085. doi: 10.1002/hep.23589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moldave K., Meister A. Synthesis of phenylacetylglutamine by human tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 1957;229:463–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO . Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation. Vol. 935. 2007. pp. 1–270. (Who Tech Rep Ser). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables