Abstract

Introduction:

The Evidence-Based Care of the Elderly Health Guide is a clinical guide with cross-references for care recommendations. This guide is an innovative adaptation of the Rourke Baby Record to support elderly care. In 2003, the guide was published with an endorsement from the Health Care-of-the-Elderly Committee of the College of Family Physicians of Canada. Since then, physicians have used the guide as a checklist and a monitoring tool for care to elderly patients.

Objective:

We will update the 2003 Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide with current published evidence-based recommendations.

Methods:

This was a mixed methods study consisting of (1) the creation of a list of topics and corresponding guidelines or recommendations, (2) two focus group discussions among family physicians (n = 12) to validate the list for relevance to practice, and (3) a modified Delphi technique in a group of ten experts in Care of the Elderly and geriatrics to attain consensus on whether the guidelines/recommendations represent best practice and be included.

Results:

The initial list contained 43 topics relevant to family practice, citing 49 published guidelines or recommendations. The focus group participants found the list of topics and guidelines potentially useful in clinical practice and emphasized the need for user-friendliness and clinical applicability. In the first online survey of the modified Delphi technique, 93% (63/66) of the references attained consensus that these represented standards of care. The other references (3/66) attained consensus in the second online survey. The final list contained 47 topics, citing 66 references.

Conclusion:

The Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide is a quick reference to geriatric care, reviewed for relevance by family physicians and a panel of experts. The Guide is intended to be used in primary care practice.

Keywords: care of the elderly, guidelines, care

Introduction

The Evidence-Based Care-of-the-Elderly (COE) Health Guide is a clinical guide with cross-references to care recommendations.1 This guide was an innovative adaptation of the 1998 Rourke Baby Record, an adaptation to the care for older persons.2 In 2003, the guide was published with an endorsement from the Health Care of the Elderly Committee of the College of Family Physicians of Canada. Since then, physicians across Canada have used the guide as a checklist and a monitoring tool for provision of care to elderly patients.

To our knowledge, there are no guides similar to the COE Health Guide that have been published. However, various assessment forms for clinical care of older persons have been published. For frailty assessment, for example, some of the forms used are the Frailty Index, the Edmonton Frailty Scale, and the Clinical Frailty Scale.3 For nutritional assessment, a review reported 17 tools, including the Mini Nutritional Assessment form.4 There are numerous guidelines for addressing polypharmacy. Common examples include the Beers Criteria,5 the Screening Tool for Older Persons Prescribing (STOPP) criteria,6 the Laroche et al7 list of PIMs, and multiple country/region-specific FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged)8 Lists. Although there are numerous guidelines for geriatric syndromes, and primary and secondary prevention, it is recognized that the application of individual disease-oriented guidelines to patients with multimorbidity is not feasible and can be potentially harmful.9 There are many guidelines that address care for older adults with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. These generally describe guiding principles as opposed to specific recommendations for common conditions encountered in older adults.10 With limited time and so much information available to primary care physicians, there is a need for an evidence-informed summary such as the Evidence-Based COE Health Guide.

The population of older patients is increasing. In Canada, as of July 1, 2020, 18.0% (6 835 866 individuals) were 65 years of age and older, with this segment of the population estimated to increase to over 10 million by 2037.11,12 Given these demographic changes, primary healthcare professionals are expected to provide care to more seniors.13 Training, policy changes, and new models of care will be needed to provide quality care to the increasing number of older persons.14 We created the COE Health Guide to be a useful tool for primary care providers in the care for older adults.

The objective of this study was to update the 2003 Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide with current published evidence-based recommendations. Part of the inspiration for this updated version comes from the AAFP Summary of Recommendations for Clinical Preventative Services.15 This study aims to have the updated Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide into an easily accessible quick reference tool for primary care practitioners on commonly encountered conditions and preventative care for seniors.

Methods

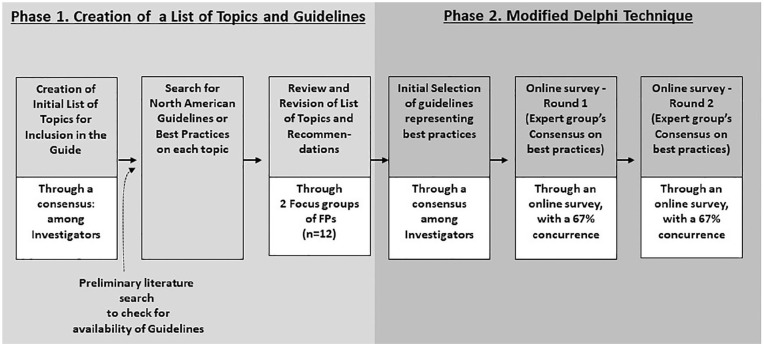

This study received approval from the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board (Study ID No. Pro00052024). This was a mixed methods study involving 2 phases (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phases of the study.

Phase 1—Creation of a List of Topics and Guidelines

This phase consisted of the creation of a list of topics relevant for care of adults 65 and older and their corresponding guidelines or recommendations.

The investigators, through consensus, generated a list of topics for possible inclusion in the guide. Relevance to family practice was the primary consideration for inclusion in the list.

We performed a limited search for relevant guidelines or recommendations (in the absence of guidelines) on these topics. The search for guidelines and recommendations was done using a keyword search in the following online sites and databases: Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care, United States Preventative Services Taskforce, National Guideline Clearinghouse, and PubMed. This search was supplemented with the investigators’ knowledge/use of existing guidelines and with Google search. The investigators then assessed the guidelines and recommendations for relevance to family practice. The strength and quality of evidence in the guidelines were not reassessed by the investigators but rather reported verbatim from the source documents. Only a select number of statements from each guideline/recommendation were chosen. The reason for this was to avoid the creation of a very lengthy document. The intent in the final COE Health Guide was to provide links to the source documents for users to access.

The initial list of topics and guidelines was then presented to 2 groups of community-based family physicians via face-to-face focus group discussions (Feb 2018). The objective of the focus group discussions was to elicit feedback from the family physicians on the relevance of the list of topics and guidelines to family practice. The first group of physicians (n = 8) represented family physicians from academic clinics affiliated with the Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta. The second group of physicians (n = 4) represented family physicians from a non-academic-affiliated group of clinics.

Phase 2—Modified Delphi Technique

After the 2 focus groups, the investigators did not perform a formal thematic analysis but rather independently reviewed the transcripts, followed by a group discussion and consensus based on suitability and feasibility of the revisions. A modified list was then used in a modified Delphi method to attain consensus among a group of experts as to whether the list of topics, guidelines, or recommendations represent current best practices.

The investigators invited 7 Care of the Elderly Physicians (family physicians with extra training in providing care to the older adult)16 and 3 Geriatricians (physicians trained in geriatric medicine) to serve as the panel of experts participating the Modified Delphi technique. The panel of experts assessed the lists of guidelines and recommendations on whether these represent current standards of care. The Modified Delphi Technique consisted of 2 rounds of online survey via SurveyMonkey. The first survey was done between October 2019 and January 2020. After the first survey, those recommendations receiving ≥67% agreement were considered standards of care. The investigators then reviewed the comments and adjusted the list of recommendations accordingly. Those recommendations receiving <67% agreement were revisited by the investigators and carried forward to the second online survey. The second online survey (May 2020-June 2020) was then sent to the expert panel and the same consensus process was followed. The comments from the second survey were reviewed and the list of guidelines finalized. See Supplemental Appendix A for details on the modified Delphi process.

Outcomes

A list of topics and guidelines and recommendations was finalized.

Results

List of Topics and Guidelines/Recommendations

The initial list contained 43 topics relevant to family practice, citing 49 published guidelines or recommendations. Each topic had several statements quoted verbatim from 1 or 2 published guidelines or recommendations. For ease of use, the list was divided into 6 sections: Geriatric Syndromes (6 topics, 10 references), Geriatric-Specific Concerns (8 topics, 11 references), Geriatric Safety and Caregiving Issues (8 topics, 12 references), Primary Prevention in Geriatrics (10 topics, 16 references), Secondary Prevention (Screening) in Geriatrics (13 topics, 13 references), and Other Preventative areas (2 topics, 4 references). See Supplemental Appendix B for the initial list of topics.

Feedback on relevance to clinical practice

In summary, the focus group participants found the list of topics and guidelines potentially useful in clinical practice. They wanted a “user-friendly” guide for management of primary geriatric conditions. The participants appeared less interested in reading about the quality of the evidence as they were in reading about protocols for use in primary care.

The participants’ feedback could be grouped into 3 themes. First, there was feedback related to the modification of the content: The expansion or change in the scope of the topics already listed or the inclusion of new topics. Second, there was feedback related to the format of the document: Increasing the usability of the document (eg, search function) and improving the ease of applying the content clinically (eg, accessibility to team members). And, third, there was feedback related to the applicability of the topics to older persons: ascertaining that the guidelines are suited to older persons and the feasibility of the recommendations to local set-up.

Modified Delphi technique

Based on the feedback from the focus group discussions, the investigators modified the content of the COE Health Guide. The revised guide contained 47 topics, citing 66 references in all.

The revised Guidelines were sent to our expert panel for the first online survey. Consensus on the guidelines or recommendations was attained on 93% of the references (63/66) indicating that these guidelines represented standards of care. Forty-seven percent (31/66) of the guidelines or recommendations attained consensus with all 10 experts; 28.8% (19/66) with 9 experts; and 12.1% (8/66) with 8 experts. Only 4.5% (3/66) of references did not attain consensus (ie, only attained agreement from 6/10 experts). These guidelines or recommendations from the 3 references that did not reach consensus were reviewed by the investigators and had their contents revised. These references were then sent out for the second survey, this time achieving consensus with all ten experts. The final COE Health Guide consists of 47 topics, grouped into 6 sections, citing 66 references. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Final List of Topics and Guidelines/Recommendations.

| Topics | Ref | |

|---|---|---|

| Section A. Geriatric syndromes (6 topics, 10 ref) | 6 | 10 |

| (1) Delirium (1 ref); (2) Dementia and mid cognitive impairment (2 ref); (3) Dementia-behavioral and psychological symptoms (1 ref); (4) Falls (1 ref); (5) Polypharmacy and medication review (2 ref); (6) Urinary incontinence (3 ref) | ||

| Section B. Geriatric specific concerns (7 topics, 10 ref) | 7 | 10 |

| (7) Chronic pain (1 ref); (8) Constipation and fecal incontinence (4 ref); (9) Decubitus ulcer (1 ref); (10) Insomnia (1 ref); (11) Leg edema (1 ref); (12) Parkinson’s disease (1 ref); (13) Severe nutritional risk (1 ref) | ||

| Section C. Geriatric safety and caregiving issues (8 topics; 12 ref) | 8 | 12 |

| (14) Caregiver burden (1 ref); (15) Decision-making capacity assessment (DMCA; 3 references); (16) Elder abuse (1 ref); (17) Environmental safety (2 references); (18) Fitness to drive (1 ref); (19) Frailty scales (2 references); (20) Goals of care (1 ref); (21) Medical assistance in dying (1 ref) | ||

| Section D. Primary prevention in geriatrics (10 topics, 16 ref) | 10 | 16 |

| (22) Diet and physical activity (3 ref); (23) Oral health (1 ref); (24) Osteoporosis (1 ref); (25) Sun protection (1 ref); (26) Use of tobacco, alcohol, and Cannabis (3 ref); (27) Vaccination: hepatitis A and B for travelers (1 ref); (28) Vaccination: herpes zoster/shingles (2 references); (29) Vaccination: influenza (2 references); (30) Vaccination: pneumococcus (1 ref); (31) Vaccination: tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis (1 ref) | ||

| Section E. Secondary prevention (screening) in geriatrics (14 topics; 14 references) | 14 | 14 |

| (32) Abdominal aortic aneurysm (1 ref); (33) Breast cancer (1 ref); (34) Cervical cancer (1 ref); (35) Chronic kidney disease (1 ref); (36) Colorectal cancer (1 ref); (37) Coronary heart disease (1 ref); (38) Depression (1 ref); (39) Diabetes-type II (1 ref); (40) Dyslipidemia (1 ref); (41) Hearing loss (1 ref); (42) Hypertension (1 ref); (43) Lung cancer (1 ref); (44) Prostate cancer (1 ref); (45) Visual impairment (1 ref) | ||

| Section F. Other preventative areas (2 topics; 4 ref) | 2 | 4 |

| (46) Atrial fibrillation/low molecular weight heparin (2 ref); (47) Sexuality in older age (2 ref); |

Abbreviation: Ref, reference(s).

The list, divided into 6 sections, consisted of 47 topics citing 66 references. See Supplemental Appendix C for the full list.

The format of the Final COE health guide

The final COE Health Guide is available as an online PDF file with font-size and formatting suited for reading on mobile phones (Available from: https://sites.google.com/ualberta.ca/coe-health-guide/home). If the file is opened in Apple Books, the file becomes searchable. Otherwise, the file is scrollable, with a Table of Contents that has links to all the topics and, at the end of each topic, a link back to the contents is provided.

Each topic has the same formatting. It starts with the citation and an online link to the reference. Then, a list of select recommendations/guidelines follows. The quality of evidence, as published by the reference, is provided verbatim. Readers who want to read more of the reference could go online to the original reference. Comments from the investigators and panel of experts are added as notes.

Discussion

The COE Health Guide consists of a list of topics, with select recommendations and online links to references for each topic. The list was reviewed by a panel of family physicians for relevance to practice and adjudged by a group of COE/Geriatrics experts to see if they reflected standard of care. In this update, the ease of use has been vastly improved and the process for review of topics, recommendations, and references much more rigorous.

Use in Clinical Practice

With a growing population of older persons, a guide for primary care healthcare providers is important. The aim of the 2021 COE Health Guide is to be used as a quick reference by various members of the primary healthcare team. The investigators only selected recommendations that were most commonly encountered in practice. The reason for this is to keep the COE Health Guide manageable in length. When the user wants more details, links to the original references are provided. The list was not intended to be a manual of diagnostic and therapeutic options. Rather, the COE Health Guide functions as a quick reference for use in the primary care clinic.

Format

The format of the COE Health Guide varied from the 2003 Health Guide. In 2003, the COE Health Guide was designed as a form. The current COE Health Guide is formatted as a list. This is due to the number of topics and recommendations. Listing all the recommendations as a form would have created a form that is too lengthy for clinical use. It is also now available electronically and searchable for ease of use.

There are numerous guidelines often conflicting relevant to the care of the older adult in primary practice. There is a need for a quick reference of the main topics encountered with recommendations and relevant references.

Next steps

The COE Health Guide will be accessible for free and will be available in a mobile form. The authors will update the COE Health Guide as new references are published. The authors encourage users to suggest topics and references for inclusion in the COE Health Guide, to improve on its clinical usefulness.

Limitations

The creation of the Health Guide was limited by the available resources. The investigators did not appraise the quality of evidence because undertaking systematic reviews on the numerous topics was beyond the authors’ resources. In comparison, the Rourke Baby Record,17 for example, performed close to a hundred systematic searches.

Conclusion

The Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide is a quick reference to geriatric care, reviewed for relevance by family physicians and a panel of experts. The COE Health Guide is intended to be used in primary care practices.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501327211044058 for The Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide by Jean A.C. Triscott, Bonnie Dobbs, Lesley Charles, James Huang, David Moores and Peter George Jaminal Tian in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpc-10.1177_21501327211044058 for The Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide by Jean A.C. Triscott, Bonnie Dobbs, Lesley Charles, James Huang, David Moores and Peter George Jaminal Tian in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the family physicians, Care of the Elderly physicians, and geriatricians who reviewed and provided feedback on earlier versions of the Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide. They are listed in the final Health Guide.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Northern Alberta Academic Family Medicine Fund, Department of Family Medicine, University of Alberta; Covenant Health Research Grant

ORCID iD: Peter George Jaminal Tian  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0682-082X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0682-082X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Triscott JA, Handfield-Jones RS, Bell-Irving KA, et al. Evidence-based care of the elderly health-guide. Geriatr Today. 2003;6:36-42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panagiotou L, Rourke LL, Rourke JT, Wakefield JG, Winfield D.Evidence-based well-baby care. part 1: overview of the next generation of the rourke baby record. Can Fam Physician. 1998;44:558-567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dent E, Kowal P, Hoogendijk EO.Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: a review. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;31:3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isautier JMJ, Bosnić M, Yeung SSY, et al. Validity of nutritional screening tools for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(10):1351.e13-1351.e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American geriatrics society 2019 updated AGS beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Bouthier F, Merle L.Inappropriate medications in the elderly. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85(1):94-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M; FORTA. The EURO-FORTA (fit fOR the aged) list: international consensus validation of a clinical tool for improved drug treatment in older people. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(1):61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW.Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muth C, Blom JW, Smith SM, et al. Evidence supporting the best clinical management of patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: a systematic guideline review and expert consensus. J Intern Med. 2019;285(3):272-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canada’s senior outlook: uncharted territory. 2017. Accessed May 25, 2021. https://www.cihi.ca/en/infographic-canadas-seniors-population-outlook-uncharted-territory

- 12.Statistics Canada. Annual Demographic Estimates: Canada, Provinces and Territories 2020. Catalogue no 91-215-X. Statistics Canada; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slade S, Shrichand A, DiMillo S.Health Care for an Aging Population: A Study of How Physicians Care for Seniors in Canada. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaherty E, Bartels SJ.Addressing the community-based geriatric healthcare workforce shortage by leveraging the potential of interprofessional teams. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S400-S408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Family Physicians. Summary of Recommendations for Clinical Prefventive Services. American Academy of Family Physicians; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowler N, Wyman R. eds. Residency Training Profile for Family Medicine and Enhanced Skills Programs Leading to Certificates of Added Competence. College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rourke Baby Record. Literature review – Rourke Baby Record. 2020. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.rourkebabyrecord.ca/literature_review

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501327211044058 for The Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide by Jean A.C. Triscott, Bonnie Dobbs, Lesley Charles, James Huang, David Moores and Peter George Jaminal Tian in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpc-10.1177_21501327211044058 for The Care-of-the-Elderly Health Guide by Jean A.C. Triscott, Bonnie Dobbs, Lesley Charles, James Huang, David Moores and Peter George Jaminal Tian in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health