Abstract

The islets of Langerhans of the pancreas are the primary endocrine organ responsible for regulating whole body glucose homeostasis. The use of isolated primary islets for research development and training requires organ resection, careful digestion, and isolation of the islets from nonendocrine tissue. This process is time consuming, expensive, and requires substantial expertise. For these reasons, we sought to develop a more rapidly obtainable and consistent model system with characteristic islet morphology and function that could be employed to train personnel and better inform experiments prior to using isolated rodent and human islets. Immortalized β cell lines reflect several aspects of primary β cells, but cell propagation in monolayer cell culture limits their usefulness in several areas of research, which depend on islet morphology and/or functional assessment. In this manuscript, we describe the propagation and characterization of insulinoma pseudo-islets (IPIs) from a rat insulinoma cell line INS832/3. IPIs were generated with an average diameter of 200 μm, consistent with general islet morphology. The rates of oxygen consumption and mitochondrial oxidation-reduction changes in response to glucose and metabolic modulators were similar to isolated rat islets. In addition, the dynamic insulin secretory patterns of IPIs were similar to primary rat islets. Thus, INS832/3-derived IPIs provide a valuable and convenient model for accelerating islet and diabetes research.

Keywords: β cell, diabetes, insulin, organoids, pseudo-islet

INTRODUCTION

The islets of Langerhans of the pancreas are central regulators of glucose homeostasis in most animals. Islets are small groups of endocrine cells and supporting tissues (i.e., endothelial, nervous) dispersed throughout the exocrine pancreas and comprise ∼2%–3% of the pancreatic mass (1). Islets consist primarily of three endocrine cell types: insulin-secreting β cells, glucagon-secreting α cells, and somatostatin-secreting δ cells whose coordinated hormone secretion regulates blood nutrient levels and use. The failure of this complex endocrine unit to sense and/or respond adequately to blood nutrient levels is ultimately responsible for all forms of diabetes.

Significant areas of diabetes research are dedicated to islet transplant, islet development, and islet function. Since insulin injection has been the most effective treatment for diabetes for nearly a century, considerable research has focused on isolated islets of Langerhans and insulin-producing cells for cell-based insulin replacement therapy (2–5). However, the use of isolated primary islets for research development and training requires regular acquisition of fresh pancreatic tissue, significant time, effort, and expertise to obtain islets before experimental initiation.

Several immortalized β cell lines derived from insulinomas such as βTC3 (6), Min6 (7), Rin (8), INS-1(9) and, a recently developed human β cell line, EndoC-βH (10) [and subsequent iterations (11, 12)] have been used as β cell surrogates to bypass the complications related to primary islet tissue. Immortalized β cells have offered invaluable insights into β cell physiology. However, insulinoma cell line monolayer growth does not reflect the physiological morphology of islets and limits their usefulness in several areas of research, which depend on islet morphology and/or functional assessment.

Previous work demonstrated that engineered and immortalized insulinoma β cell lines were capable of forming cellular aggregations/pseudo-islets, which more closely reflect primary islet morphology (13–20). Data also have shown that insulinoma-derived pseudo-islets have improved insulin secretory characteristics relative to cells propagated in monolayer culture (14, 16, 17). With this in mind, we sought to create an accessible, rapidly renewable islet model system with preserved gross isolated islet morphology and functional characteristics that could be employed to train personnel and better inform experiments before using isolated rodent and human primary islets.

In this manuscript, we describe the production and characterization of insulinoma pseudo-islets (IPIs) using the rat insulinoma cell line INS832/3 (21), derived from the parental INS-1 cell line (9). We selected the INS832/3 β cell line for its insulin secretory characteristics (21), responsiveness to incretins (22), and their ability to form well-defined aggregations. These characteristics made the INS832/3 cell line an ideal candidate for the development of a functional IPI islet model system. Using the described methodology, we generated IPIs with the general morphology, metabolic responses, and insulin secretory patterns of primary rat islets. Thus, islet-mimicking INS832/3-derived IPIs may serve as a foundational and accelerating model system for islet and diabetes research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Insulinoma Pseudo-Islet Formation

INS832/3 cells obtained from Dr. Christopher Newgard (Duke, Durham, NC), passages 35–45, were grown in T-flasks (Fisher) to ∼90% confluency in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with l-glutamine (Corning), 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Corning), and mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) in a cell culture incubator maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. The INS cell lines were derived from an X-ray-induced tumor in a male NEDH albino rat (23). On the day of pseudo-islet formation, INS832/3 cells were separated from the flask surface using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Gibco). Upon cell separation, the trypsin/cell solution was immediately diluted with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS, Corning), transferred to 50-mL conical tube, and centrifuged at 232 g for 3 min. The supernatant was aspirated, and the cell pellet was resuspended in HBSS and centrifuged for 3 min. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in HBSS using gentle trituration using a wide-orifice pipette tip to break up any cellular aggregations. The cellular suspension was then passed through a 40-µm exclusion filter (Falcon). After the cell suspension was passed through the filter, the tube and filter were rinsed to ensure collection of all cells < 40 µm. The filtered cellular suspension was again centrifuged for 3 min and the subsequent cell pellet was resuspended in RPMI-1640 using gentle trituration. Approximately 1 million cells/mL were transferred to suspension flask (ABLE Biott, Tokyo, Japan) and placed on a magnetic stir plate (Chemglass Life Sciences, Vineland, NJ) contained within a cell culture incubator maintained at 37°C-5% CO2 with a stir speed of 60 RPM. Cells were cultured for at least 2 days before assessment. For experiments requiring culture longer than 3 days, ∼80% of the culture media was replaced every 3 days.

For cryopreservation, IPIs were suspended in 50% FBS, 40% RPMI 1640, and 10% DMSO (Sigma) and transferred to cryogenic vials (Corning), which were placed in Nalgene Cryo 1°C Freezing container and stored overnight at −80°C. The cryopreserved IPIs were then transferred to liquid nitrogen storage for at least 2 days before assessment. For subsequent use the IPIs were rapidly thawed and transferred to suspension culture flask containing RPMI-1640 media.

Primary Rat Islet Isolation and Culture

Primary islets were isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats at the Harvard University Joslin Diabetes Center using a procedure previously described (24) under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval. The islets were shipped to the University of Arizona in Wilson-Wolf culture vessels and assessed after overnight culture.

Immunocytochemistry

INS832/3 insulinoma pseudo-islets (IPIs) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura, Torrance, CA). Sections (5 µm) were mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). The sections were washed in 1× PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X (BioRad). Sections were blocked with 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and incubated over night at 4°C with 1:500 of a guinea pig anti-insulin primary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. PA1-26938, RRID:AB_794668). Sections were then incubated with a donkey anti-guinea pig Alexa 488-labeled secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, Cat. No. 706-545-148, RRID:AB_2340472), counterstained with DAPI (Roche), and mounted with Flouromount G (Invitrogen). Sections were imaged using a Keyence BZ-X710 fluorescence microscope using a PlanApo-λ 20X 0.75/1.00 mm objective (Keyence Co., Osaka, Japan).

To determine the percentage of insulin-positive cells in IPIs, the hybrid cell count module (Keyence, Osaka, Japan) was used to identify DAPI-positive nuclei. The count area was expanded 1–2 pixels from the nuclear edge and this area was separated into distinct cells. Size exclusion was used to eliminate cellular groupings. The DAPI- and insulin-positive areas within the expanded target area were obtained. The DAPI area was subtracted from the target area, yielding a perimeter area surrounding the DAPI-labeled nucleus. The insulin area was divided by the perimeter area and a ratio greater than 0.5 was considered an insulin-positive cell. The number of insulin-positive cells was divided by the total number of DAPI-positive cells to yield the percentage of insulin-positive cells within the IPI samples.

Fluorescein Diacetate and Propridium Iodide Cellular Viability Assessment

Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) and propidium iodide (PI) were used to determine the viability of IPIs, according to the NIH Clinical Islet Transplantation Consortium (25). A sample of IPIs was placed in 35-mm cell culture dish with 1× DPBS without calcium or magnesium. PI (Sigma Aldrich) and FDA (Sigma Aldrich) were then added to the solution to a final concentration of 14.34 µm and 0.46 µm, respectively. IPIs were imaged using a BZ-X710 Keyence Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). Images were analyzed by two independent researchers using a custom ImageJ script, which measured the FDA and PI signal from the entire image. The FDA area was divided by the total fluorescent area (FDA and PI) to calculate the percentage viability of the IPI preparation. Values are presented as the average of measurements obtained by the two independent observers.

IPI Size Distribution

Three independent samples of IPIs from each preparation were placed in islet counting plates (BioRep Technologies, Inc., Miami Lakes, FL) and imaged using a BioRep Islet Cell Counter ICC-03 (BioRep Technologies, Inc.). The diameter of the IPIs was measured manually using the software provided with the BioRep Islet Cell Counter ICC-03. Size distribution is presented as the percentage of the total population.

Oxygen Consumption Rate

For static measurements of oxygen consumption, sealed water-jacketed titanium chambers (Instech Laboratories, Inc., Plymouth Meeting, PA) were used to measure oxygen consumption rate (OCR) from IPIs as previously described (26). IPIs were suspended in serum-free ME-199 media (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) and placed in chambers maintained at 37°C. The chambers were sealed and pO2 was measured over time using fiber optic sensors and NeoFox Viewer software (Ocean Optics, Inc., Dunedin, FL). The change in pO2 over time was normalized to the DNA content of each chamber. Values are presented as nmol O2/min × mg DNA.

For dynamic measurements of oxygen consumption, IPIs were placed in customized perifusion chambers with inlaid FOSPOR oxygen-sensing patches at the fluid interface of the media inlet and outlet (BioRep Technologies, Inc., Miami Lakes, FL). The low pulsatility-peristaltic pump of a BioRep perifusion system pushed Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate (KRB) containing (in mM) 137 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 25 NaCO3, 20 HEPES, and 0.25% BSA (pH 7.4) at a rate of 30 µL/min through a sample chamber containing IPIs immobilized in Bio-Gel P-4 Gel (BioRad). The pO2 was measured each minute at the inlet and outlet of the perifusion chamber using fiber optic sensors and NeoFox Viewer software (Ocean Optics, Inc., Dunedin, FL). The pO2 values measured at the outlet of the chamber were subtracted from the mean of the inlet values to yield the oxygen consumption by the IPIs. The difference in pO2 between the mean inlet value and the outlet value at each minute was normalized to DNA. Values are presented as nmol O2/mg DNA.

DNA Measurement

IPIs were placed in a 1M solution of ammonium hydroxide (Fisher) with 0.2% Triton X‐100 (BioRad) in nanopure H2O. IPIs were lysed using sonication (Sonic Dismembrator Model 500, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). A Quant‐iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit (Life Technologies) was used to measure the concentration of DNA in each sample. Samples were run in quintuplicate. Samples were read on a SpectraMax M5 plate reader equipped with SoftMax Pro software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

NAD(P)H Measurements

After 1 day of stirred suspension culture, IPIs were plated onto #1 coverslips harbored in six well plates containing RPMI-1640 and allowed to attach to the coverslip for 1–2 days in a cell culture incubator maintained at 37°C-5% CO2. IPIs attached to coverslips were preincubated in HBSS containing (in mM) 5 KCl, 0.3 KH2PO4, 138 NaCl, 0.2 NaHCO3, 0.3 Na2HPO4, 20 HEPES, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.4 MgSO4, and 1.0 glucose (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 20 min. IPIs were then placed in a chamber held at 37°C mounted on the stage of an inverted Olympus IX-70 microscope equipped with a ×40 1.4 numerical aperture (NA) ultrafluor objective and a 150 W Xe lamp excitation source. NAD(P)H fluorescence was excited at 360 nm (10 nm BP) and the emitted light was filtered at 450 nm (30 nm band pass), before focusing the cell image onto a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Photometrics CH-250). The fluorescence output is related primarily to mitochondrial NADH levels in a variety of cell types, including β cells (27, 28).

Perifusion and Insulin Measurement

An automated perifusion system (Biorep Technologies) was used to dynamically measure insulin secretion from IPIs. A peristaltic pump pushed Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate (KRB) containing (in mM) 137 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 25 NaCO3, 20 HEPES, and 0.25% BSA (pH 7.4) at a rate of 100 µL/min through a sample chamber containing IPIs or primary rat islets immobilized in Bio-Gel P-4 Gel (BioRad). The perifusate was collected in 96-well plates using an automatic fraction collector. Hundred microliters volumes were collected every minute and samples were stored at −80°C until insulin was measured from select time points.

For static insulin secretion assays, three replicates of IPIs were placed on Millicell Cell Culture inserts (Millipore) and placed in a 24-well plate. Islets were equilibrated in KRB supplemented with 2.8 mM glucose for 45 min at 37°C and then incubated for 1 h at 37°C in KRB supplemented with 2.8 mM glucose and 16.7 mM glucose. After each incubation, media were collected and stored at 4°C until experiment completion. All samples were then stored at –80°C until insulin assay.

Insulin was measured using the rat high-range ELISA kit (Alpco). Samples were run in duplicates. Insulin was normalized to the total DNA from the IPIs or primary rat islets in each chamber. DNA was quantified using the same methodology described in DNA Measurement.

Statistics

All values are presented as means ± SE, unless stated otherwise. Significance was determined with an unpaired t test or ordinary one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Tukey’s test calculated by GraphPad Prism 9.0. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Suspension Culture Formed Viable Insulinoma Pseudo-Islets with Islet-Like Morphology and Insulin Expression

To create a model system for β cell/diabetes research that is rapidly renewable, limits the use of animals, and mimics islet morphology and function, we sought to create pseudo-islets from an insulinoma cell line. INS832/3 were chosen as a model for the following reasons: 1) limited availability of human β cells lines, 2) historic experimental use of primary rodent islets in diabetes research, and 3) the glucose-stimulated and potentiated insulin secretory properties of the INS832 cell lines, including secretion of human insulin (21). We also attempted to create IPIs from Min6 and βTC3 cell lines using the same methodology, however, these cell lines did not aggregate as effectively as INS832/3 cells, thus we did not continue our investigations of these cell lines.

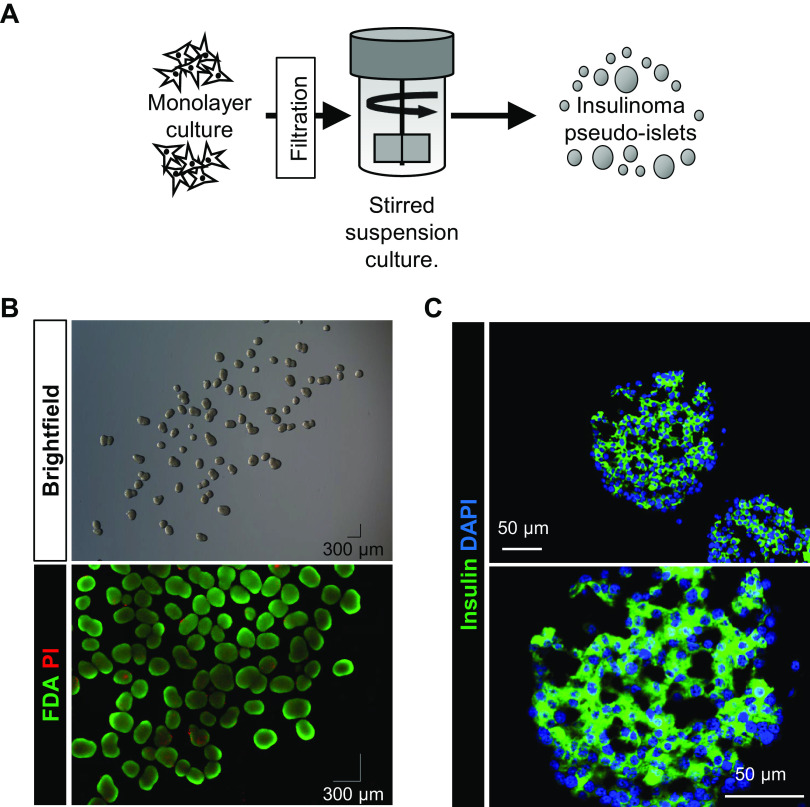

After 3 days in stirred suspension culture, INS832/3 cells formed viable insulinoma pseudo-islets (IPIs) (measured by FDA/PI; 93.3 ± 1.41%; n = 5) similar in appearance to primary islets (Fig. 1B). Approximately 80% of IPIs were between 151 and 300 µm in size (Fig. 2A; n = 5), generally reflecting the size of primary islets. To ensure that insulin expression was maintained in suspension culture, IPIs were immunolabeled for insulin and 71% (n = 23,192 DAPI+ nuclei) of insulinoma cells within the IPIs were found to express insulin (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

INS832/3 insulinoma cells formed viable, insulin-expressing aggregates when cultured in stirred suspension. A: INS832/3 cells were grown in monolayer culture, separated from the flask surface, and filtered. Cells were then placed in stirred suspension culture. After 3 days of stirred suspension culture, INS832/3 insulinoma pseudo-islet morphology and viability were assessed by brightfield imaging and FDA/PI staining (B; viability mean = 93.3 ± 1.4%; n = 5 independent images). C: INS832/3 pseudo-islets were labeled for insulin and DAPI. Insulin was expressed in 71% (n = 6 independent images; 23 IPIs, 192 DAPI+ nuclei) of cells. IPI, insulinoma pseudo-islet; FDA, fluorescein diacetate; PI, propidium iodide.

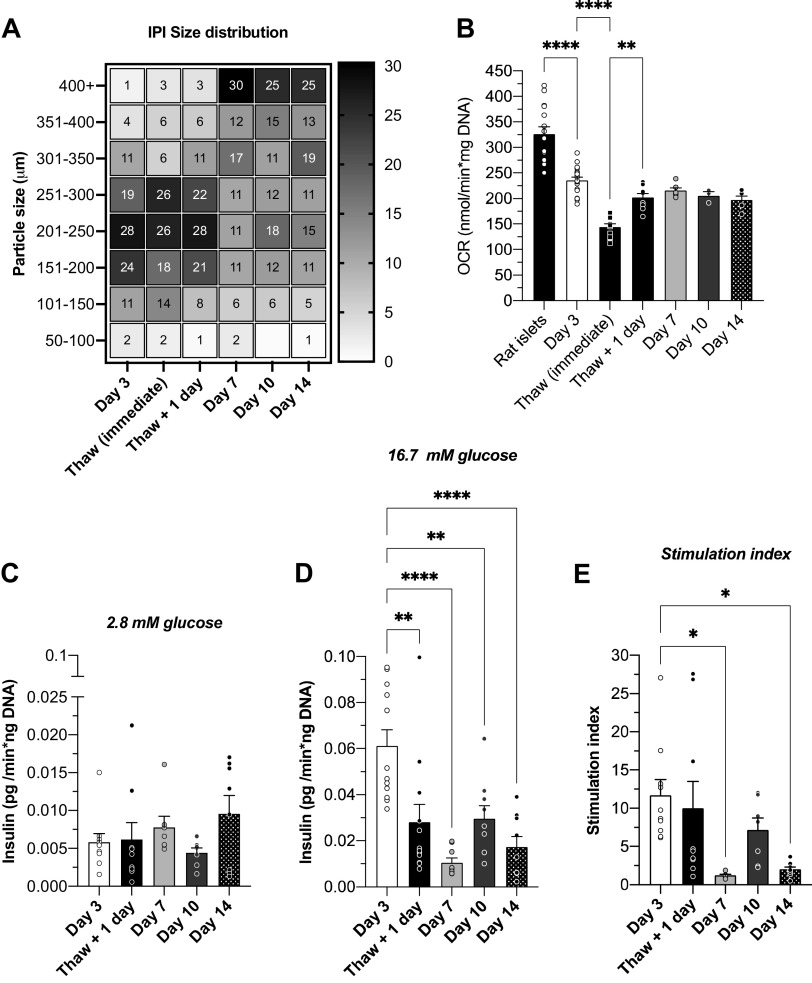

Figure 2.

Oxygen consumption by INS832/3 pseudo-islets. A: size distribution of IPIs after cryopreservation/thaw [Thaw (immediate): n = 3; 61 IPIs; Thaw + 1 day: n = 4; 964 IPIs] and 3 days (n = 9; 1,028 IPIs), 7 days (n = 4; 329 IPIs), 10 days (n = 3; 343 IPIs), and 14 days (n = 3; 131 IPIs) in suspension culture depicted on a heat map. The gradient (and the numbers in each square) on the right y-axis depicts the percentage of the IPI population in each size bin specified on left y-axis. B: the static oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of INS832/3 pseudo-islets cultured in suspension for 3 days was 235.3 ± 6.5 nmol/min × mg DNA (n = 6; 18 replicates) and primary rat islet OCR was 326.1 ± 14.2 (n = 5; 15 replicates). IPI OCR was also measured immediately after thaw from cryopreservation (mean = 144.7 ± 6.0; n = 4; 12 replicates), 1 day after thaw (202.1 ± 7.5; n = 3; 9 replicates), and after 7 (215.3 ± 5.4; n = 2; 3 replicates), 10 (205.8 ± 7.4; n = 1; 3 replicates, and 14 (197.1 ± 7.8; n = 2; 6 replicates) days in suspension culture. Basal insulin secretion (BIS; C) and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS; D) were measured and used to calculate the stimulation index (SI; E) of IPIs on day 3 (n = 4/10–12 replicates; BIS = 0.006 ± 0.001; GSIS = 0.061 ± 0.007; SI = 11.7 ± 2.1), day 7 (n = 3/9 replicates; BIS = 0.008 ± 0.002; GSIS = 0.011 ± 0.002; SI = 1.2 ± 0.1), day 10 (n = 3/7–9 replicates; BIS = 0.004 ± 0.001; GSIS = 0.030 ± 0.006; SI = 7.2 ± 0.16), and day 14 (n = 3/8–9 replicates; BIS = 0.01 ± 0.002; GSIS = 0.017 ± 0.005; SI = 2.0 ± 0.33) of suspension culture and 1 day after thaw from cryopreservation (n = 4/9–12 replicates; BIS = 0.006 ± 0.002; GSIS = 0.028 ± 0.008; SI = 10.0 ± 3.6). Data are means ± SE. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. P values: **** < 0.0001, ** ≤ 0.0003, and * < 0.05. IPI, insulinoma pseudo-islet; OCR, oxygen consumption rate.

To optimize IPI culture and use, we cultured IPIs for 14 days and periodically assessed morphology, viability, and function. IPI size increased with culture time (Fig. 2A) and IPIs fragmented between day 10 and 14. Fragmentation and abnormal shape by day 14 made spheroidal size measurement difficult and resulted in apparent redistribution of size on day 14 (Fig. 2A). We also observed a nonsignificant decrease in OCR with increased culture time (Fig. 2B), suggesting some decreased viability and/or decreased metabolic function with extended culture time.

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) generally decreased over 14 days of culture [Fig. 2, C–E; stimulation index (SI): day 3 = 11.7 ± 2.1; day 7 = 1.2 ± 0.1, day 10 = 7.2 ± 1.6, and day 14 = 2.0 ± 0.3]. With these data, we determined that IPI morphology, viability, and function were optimal and most similar to primary islets after 3 days of suspension culture.

IPI Viability Decreased and Insulin Secretion Was Preserved Post Cryopreservation

To assess if IPIs could be cryopreserved and reconstituted effectively, we cultured IPIs in suspension culture for 3 days, cryopreserved the IPIs, thawed the IPIs, and assessed viability and function by OCR and static GSIS assay. Immediately post-thaw, IPI OCR was decreased relative to IPIs before cryopreservation (Fig. 2B; Thaw (immediate) mean = 144.7 ± 6.0 nmol O2/min/ng DNA). The thawed IPIs were placed in suspension culture overnight. After overnight culture, IPI OCR was reduced relative to IPIs before cryopreservation, however, OCR appeared to increase relative to IPI OCR immediately after thaw (Fig. 2B; Thaw + 1 day mean = 202.1 ± 1.5). IPI GSIS was assessed after 1 day culture from initial thaw. Insulin secretion in 16.7 G was significantly decreased relative to IPIs before cryopreservation (Fig. 2, C–E), however, the stimulation index (SI = 9.96 ± 3.6) was similar.

Insulinoma Pseudo-Islets Were Metabolically Responsive to Glucose

To compare the viability and metabolic activity of IPIs and primary rat islets, we measured oxygen consumption (OC) from IPIs and rat islets. The static OC rate (OCR) in IPIs was lower than primary rat islets (Fig. 2B; IPI OCR = 235.3 ± 6.5; n = 6/18 replicates vs. rat islet OCR: 326.1 ± 14.2; n = 5/15 replicates; P < 0.0001), indicating reduced metabolic activity relative to primary rat islets (29).

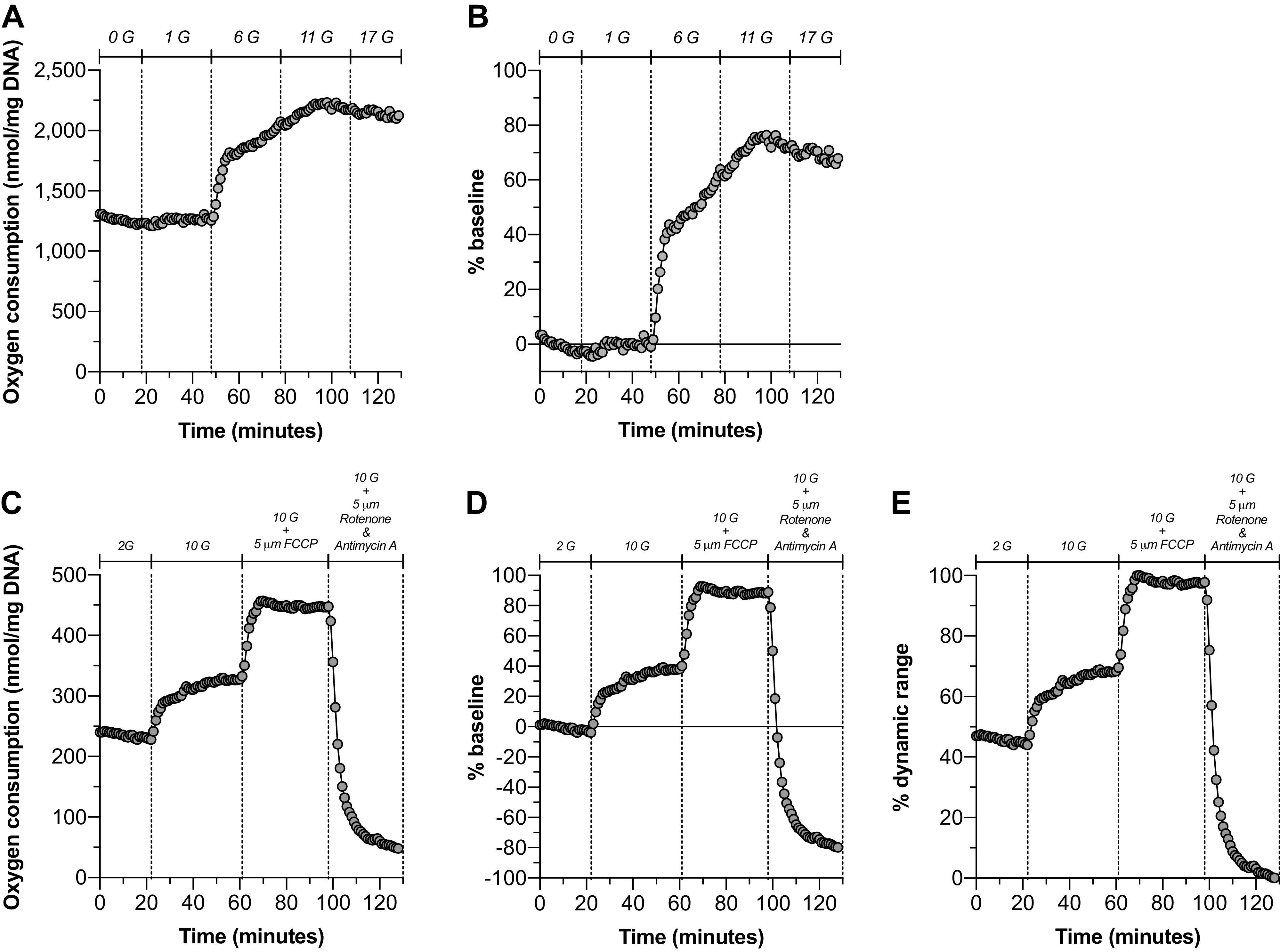

We also measured dynamic OC by IPIs in response to glucose and metabolic inhibitors (Fig. 3, A–E). Using a glucose ramp, we found that OC by IPIs did not increase in response to an increase in glucose from 0 to 1 mM (Fig. 3, A and B), unlike other insulinoma cell lines which can be stimulated at relatively low glucose concentrations (6, 8, 30). Furthermore, we found that OC by IPIs was increased by ∼40%–60% with an elevation in glucose from 1 to 6 mM and increased an additional ∼15% further when glucose was elevated to 11 mM reaching an apparent OC plateau between 11 and 17 mM glucose (Fig. 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

INS832/3 pseudo-islets responded to increased glucose with increased oxygen consumption. Dynamic oxygen consumption (OC) of INS832/3 pseudo-islets was measured using a customized perifusion chamber (A–E). A glucose ramp (A and B; n = 1) was used to evaluate the glucose responsiveness of INS832/3 pseudo-islets. Data are presented as nmol/mg DNA (A) and as a percentage change over the baseline OCR (B). A glucose increase from 2 to 10 mM in combination with the respiratory chain inhibitors FCCP and rotenone and antimycin A was used to normalize the glucose response of INS832/3 pseudo-islets to their respiratory capacity (C–E; n = 1). Data are presented as nmol/mg DNA (C), a percentage change from the baseline OCR (D), and a percentage of the dynamic range (E). FCCP, trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone; OCR, oxygen consumption rate.

To investigate the total respiratory potential of IPIs and its relation to glucose-stimulated OC by IPIs, we used metabolic inhibitors trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and the combination of rotenone and antimycin A, which cause maximal OC and minimum OC, respectively, via differential modulation of the respiratory chain (Fig. 3, C–E) (31–33). Glucose elevation from 2 to 10 mM glucose resulted in an OC increase of ∼35% (Fig. 3, D and E). By normalizing OC values to the dynamic range of OC, defined as the difference between the maximum (FCCP-induced) and minimum (Rotenone + Antimycin A-induced) OC values, we found that IPIs utilize ∼50% of their respiratory capacity at 2 mM glucose and increase OC to ∼65% of their respiratory capacity in the presence of 10 mM glucose (Fig. 3E).

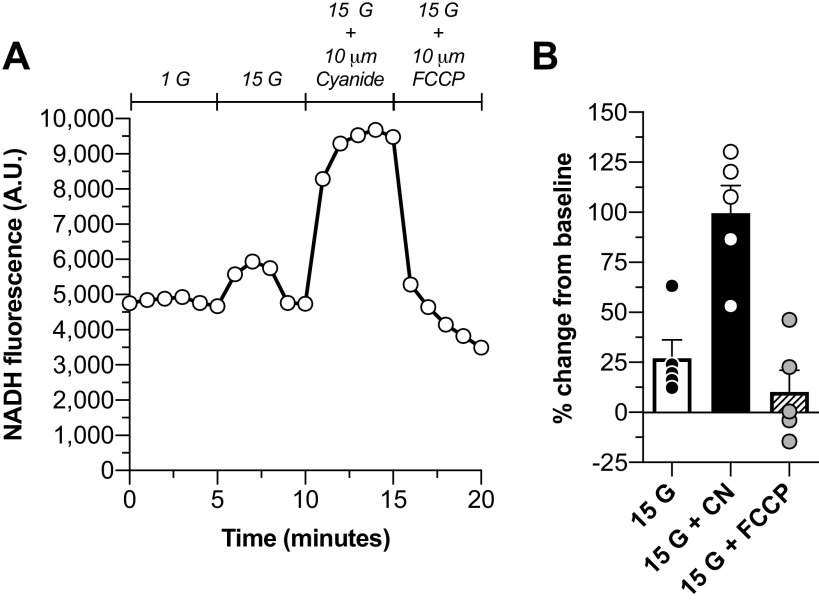

Mitochondrial Oxidation-Reduction State Was Modulated by Glucose

To evaluate the mitochondrial oxidation-reduction (redox) state of INS832/3 IPIs, we measured glucose and metabolic inhibitor-induced changes of NADH fluorescence. Glucose elevation from 1 to 15 mM induced a ∼25% increase in NAD(P)H fluorescence (Fig. 4). The maximal mitochondrial NAD(P)H signal was evaluated by addition of cyanide (CN), which blocks reducing equivalent removal. Application of CN to IPIs elicited an ∼100% increase in NADH relative to baseline values (Fig. 4B). Conversely, FCCP, which dissipates the mitochondrial membrane potential, was used to fully oxidize reducing equivalents as seen in Fig. 4A, where the NAD(P)H fluorescence dropped below baseline levels.

Figure 4.

The NADH oxidation-reduction state of IPIs changed in response to glucose and metabolic effectors. A: a representative tracing of [NAD(P)H]i fluorescence during the experimental time course in response to 15 mM glucose and respiratory chain modulators cyanide and FCCP. B: the % change in NAD(P)H signal from baseline levels (mean of the 5 values preceding glucose elevation) elicited by glucose elevation to 15 mM from 1 mM glucose (mean = 27 ± 9.2; n = 5), 10 μM cyanide (mean = 99.5 ± 13.7; n = 5), and 10 μM FCCP (mean = 10.1 ± 10.9; n = 5). Data are presented as means ± SE. FCCP, trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone; IPI, insulinoma pseudo-islet.

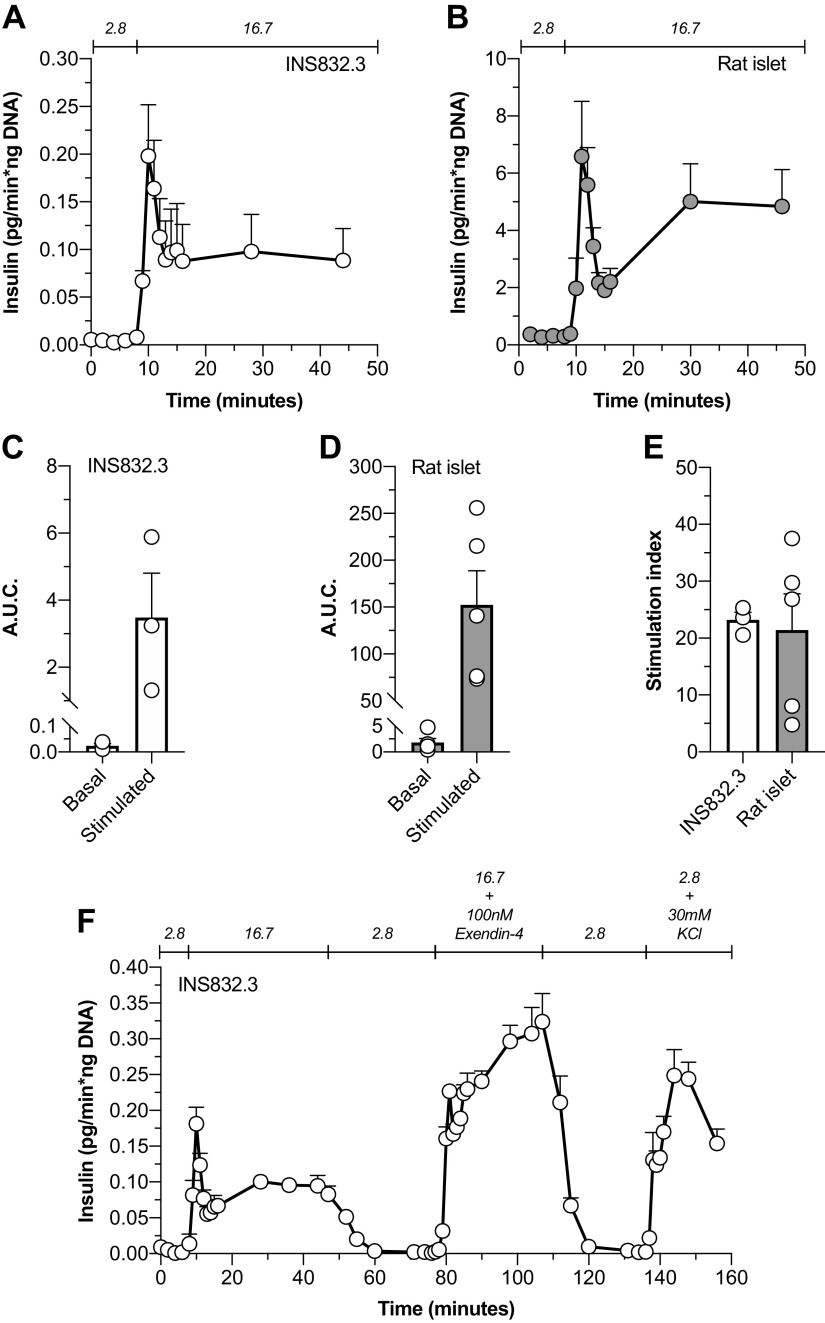

Insulinoma Pseudo-Islet Insulin Secretion Patterns Were Similar to Primary Rat Islets and Are Responsive to a GLP-1R Agonist

To explore and compare the insulin secretory patterns and capacity of IPIs relative to primary rat islets, dynamic insulin secretion was evaluated by perifusion (Fig. 5). We found that IPI glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS; Fig. 5A) mimicked the secretory patterns of primary rat islets (RI; Fig. 5B) with an initial first phase peak response to glucose and a subsequent elevated second phase secretory pattern. However, IPIs (Fig. 5C) secrete ∼75× less insulin at 2.8 mM glucose [IPI area under the curve (AUC) = 0.0241 ± 0.008, n = 3; RI AUC = 1.817 ± 0.757, n = 5] and ∼45× less insulin when stimulated with 16.7 mM glucose (IPI AUC = 3.483 ± 1.324, n = 5; RI AUC = 152.2 ± 36.62, n = 3) relative to primary rat islets (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, the IPI stimulation index (SI), defined as the ratio of the secretory rate of GSIS to basal insulin secretion, was similar to primary rat islets (Fig. 5E; IPI SI = 23.17 ± 1.40, n = 3; RI SI = 21.4 ± 6.38, n = 5). In addition, we investigated if IPIs demonstrated a return to basal levels of insulin secretion after stimulation upon reexposure to low glucose and if IPIs were responsive to the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist exendin-4. Thus, we expanded our perifusion protocol to include a return to 2.8 mM glucose after glucose stimulation and after a stimulation period with 16.7 mM glucose + 10 nM exendin-4 (Fig. 5F). IPIs appropriately “shut-off” insulin secretion after stimulation with 16.7 mM glucose and 16.7 mM glucose + 10 nM exendin-4 upon reexposure to 2.8 mM glucose (Fig. 5F). IPIs also showed a potentiated glucose-stimulated insulin secretory (PGSIS) response when exposed to 16.7 mM glucose and 10 nM exendin-4, demonstrating the presence of functional GLP1-Rs and intact second messenger signaling pathways (Fig. 5F). IPIs were also responsive to the membrane depolarization by KCl (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5.

INS832/3 pseudo-islet insulin secretion patterns were similar to primary rat islets. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by INS832/3 pseudo-islets (n = 3; A) and primary rat islets (n = 5; B) was assessed by perifusion. The basal and stimulated area under the curve (AUC) for the perifusion traces presented in A and B were calculated for INS832/3 [C; basal mean = 0.024 ± 0.01; stimulated mean = 3.5 ± 1.3 (pg/ng DNA); n = 3] and primary rat islets [D; basal mean = 1.8 ± 0.8; stimulated mean = 152.2 ± 36.6 (pg/ng DNA); n = 3]. E: the stimulation index (SI), defined as the ratio of stimulated insulin secretory rates and basal insulin secretory rates, was also calculated for INS832/3 islet-like aggregates (SI mean = 23.2 ± 1.4; n = 3) and primary rat islets (SI mean = 21.4 ± 6.4; n = 5). To further assess INS832/3 pseudo-islet insulin secretory patterns, we performed an additional perifusion (F) with a reexposure to nonstimulatory glucose after glucose stimulation and exposure to exendin-4 (10 nM) and KCl (30 mM). Data are means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

The complexity, cost, and time-consuming nature of primary islets of Langerhans research and training motivated our team to create an accessible, rapidly renewable, and representative model system for isolated islets that could be used to train personnel and inform experiments that require valuable primary islets. Previous work by several groups has shown that insulinoma cell lines form islet-like aggregates or IPIs (13–20, 34). However, previous approaches to create IPIs required relatively complex methodology, often with relatively low yields and limited functional characterization.

We demonstrated that a simple stirred suspension culture system forms highly viable IPIs similar in morphology to primary islets within 3 days of culture (Fig. 1). The relative simplicity of this model makes it highly scalable and capable of producing large quantities of IPIs within days. Islet and IPI size profiles are important, as increasing islet/IPI diameter is related to oxygen diffusion into the interior of the islet/IPI, which can affect islet function and/or survival (35, 36). A singular batch of IPIs in a 30-mL suspension flask created 30,000–50,000 islet equivalent units (IEQ) within 3 days, a process that would require 30–50 individual high-yield rat isolations. Our process allowed us to characterize several metabolic and functional aspects of the INS832/3 line, which could not be measured with monolayer cultures and to our knowledge have not been explored previously.

First, we were able to determine that the oxygen consumption rate of INS832/3 IPIs was reduced compared with isolated rat islets (Fig. 2), but greater than values that have been reported for isolated human islets (37). Dynamic measurements of IPI oxygen consumption indicated that the cells operate at ∼50% of their respiratory capacity at nonstimulatory glucose levels and increase their activity by ∼20% in the presence of stimulatory glucose (Fig. 3). Measurement of cellular oxygen consumption has been shown to be predictive of transplant outcomes (38, 39), and measurement of oxygen consumption in response to glucose and other nutrients may offer insight into β cell oxidative capacity and the mechanism by which glucose and other secretagogues stimulate insulin secretion (40–44). Changes in β cell oxidative capacity have also been implicated in β cell dysfunction in diabetes (33). Thus, an easily manipulated islet model system with OC characteristics similar to primary islets could serve as a model to investigate the link between metabolism and β cell (dys)function.

In addition, NAD(P)H fluorescence can be used to noninvasively evaluate mitochondrial oxidation-reduction (redox) potential (27). NAD(P)H fluorescence was increased when IPIs were exposed to stimulatory levels of glucose, consistent with previous findings that stimulatory levels of glucose increase the mitochondrial NADH/NAD+ ratio in rat islets (45) and NAD(P)H fluorescence in mouse islets (27, 28). Furthermore, increased NAD(P)H has been shown to be coordinated with elevations in mitochondrial respiration in INS-1 cells and isolated human islets (46). Glucose-stimulated OC and CN-induced elevation of the mitochondrial redox potential demonstrated that IPI mitochondria were not oxygen limited. Moreover, uncoupling of mitochondrial redox state from respiration with FCCP stimulated both OC and oxidation of NADH (Figs. 3 and 4). Thus, the INS 832/3 IPIs provide an islet model to evaluate oxygen limitations and delivery, which are critically important properties when evaluating islet function and developing islet transplant methods.

The spherical and nonadherent nature of the IPIs allowed our team to dynamically measure insulin secretion by INS832/3 cells in response to nonstimulatory glucose, stimulatory glucose, exendin-4, and KCl-induced membrane depolarization. Importantly, IPIs responded appropriately to nonstimulatory and stimulatory levels of glucose and displayed an “off” response after stimulation, faithfully recapitulating features of primary islets. In addition, INS832/3 IPIs were responsive to exendin-4, indicating an intact incretin response including functional expression of G-protein-coupled receptors and required downstream signaling pathways (Fig. 5). Thus, IPIs may serve to assist in high-throughput drug discovery, as previously suggested by others (14). Notably, our studies demonstrated that cryopreservation has a small effect on GSIS (Fig. 2), which could enable batch production of IPIs, cryopreservation, and thawing with experimental demand.

Although there is a range of imaginable applications of IPIs, there are also several limitations. First, IPIs are comprised only of insulinoma β cells without other islet endocrine cell types or supporting tissues such as vasculature and nervous tissues. Thus, some intra-islet signaling and interactions are likely absent, such that IPIs may not reflect the true state of the isolated islet. However, isolated primary islets contain vasculature and nervous tissues that have been separated from the organismal network, which may cause differences between in vivo and in vitro islet function. More physiologically realistic pseudo-islets could be developed. For example, pseudo-islets that contain multiple islet-endocrine cell types could be created by coculture of insulinoma cell lines with glucagonoma cell lines (47) or development of pseudo-islets optimized for transplantation studies by inclusion of cellular matrix and/or endothelial tissue (48–50).

The IPIs described here also are limited by the quantity of insulin they secrete. Although, the secretory patterns are similar to primary rat islets, IPIs secrete less insulin (45–75× less). Thus, in some experiments the user may have to use a greater number of cells relative to primary islets to reliably measure insulin secretion. In addition, insulinoma β cells do not necessarily reflect the transcriptomic or functional signatures of primary β cells (51, 52), thus any experimental results must be interpreted with caution as with any immortalized cell line (20). Despite these caveats, we believe that IPIs will serve as an islet-training tool and better inform experimental design of studies with primary islets.

In conclusion, INS832/3 pseudo-islets are metabolically responsive and exhibit insulin secretion patterns similar to primary islets. The described methodology is scalable, allowing regular and reproducible production of large quantities of IPIs that are useful for training and development of islet-based research.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) (3-SRA-2015-40-Q-R; to K. K. Papas), American Diabetes Association (1-13-BS-117; to R. M. Lynch), Health and Human Services NIH Grant (1DP3DK106933-01), and JDRF Grants (2-SRA-2018-685-S-B and 2-SRA-2014-289-Q-R).

DISCLOSURES

K. K. Papas has disclosed an outside interest in Procyon Technologies, Inc., to the University of Arizona. Conflicts of interest resulting from this interest are being managed by The University of Arizona in accordance with its policies. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.J.H., B.H., K.K.P., and R.M.L. conceived and designed research; N.J.H., C.W., N.P., A.B., M.S., E.H., C.G., and R.M.L. performed experiments; N.J.H., C.W., N.P., A.B., M.S., B.H., and R.M.L. analyzed data; N.J.H., C.W., L.V.S., K.K.P., and R.M.L. interpreted results of experiments; N.J.H. and C.W. prepared figures; N.J.H. and R.M.L. drafted manuscript; N.J.H., K.K.P., and R.M.L. edited and revised manuscript; N.J.H., C.W., N.P., A.B., M.S., B.H., E.H., C.G., L.V.S., K.K.P., and R.M.L. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gregg BE, Moore PC, Demozay D, Hall BA, Li M, Husain A, Wright AJ, Atkinson MA, Rhodes CJ. Formation of a human β-cell population within pancreatic islets is set early in life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: 3197–3206, 2012. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricordi C, Goldstein JS, Balamurugan AN, Szot GL, Kin T, Liu C, et al. National Institutes of Health-sponsored Clinical Islet Transplantation Consortium phase 3 trial: manufacture of a complex cellular product at eight processing facilities. Diabetes 65: 3418–3428, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db16-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odorico J, Markmann J, Melton D, Greenstein J, Hwa A, Nostro C, et al. Report of the key opinion leaders meeting on stem cell-derived beta cells. Transplantation 102: 1223–1229, 2018. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutherland DER, Radosevich DM, Bellin MD, Hering BJ, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, Chinnakotla S, Vickers SM, Bland B, Balamurugan AN, Freeman ML, Pruett TL. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg 214: 409–424, 2012. discussion 424–426 doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hering BJ, Clarke WR, Bridges ND, Eggerman TL, Alejandro R, Bellin MD, Chaloner K, Czarniecki CW, Goldstein JS, Hunsicker LG, Kaufman DB, Korsgren O, Larsen CP, Luo X, Markmann JF, Naji A, Oberholzer J, Posselt AM, Rickels MR, Ricordi C, Robien MA, Senior PA, Shapiro AMJ, Stock PG, Turgeon NA; Clinical Islet Transplantation Consortium. Phase 3 trial of transplantation of human islets in type 1 diabetes complicated by severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 39: 1230–1240, 2016. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Efrat S, Linde S, Kofod H, Spector D, Delannoy M, Grant S, Hanahan D, Baekkeskov S. Beta-cell lines derived from transgenic mice expressing a hybrid insulin gene-oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 9037–9041, 1988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyazaki J, Araki K, Yamato E, Ikegami H, Asano T, Shibasaki Y, Oka Y, Yamamura K. Establishment of a pancreatic β cell line that retains glucose-inducible insulin secretion: special reference to expression of glucose transporter isoforms. Endocrinology 127: 126–132, 1990. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-1-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark SA, Burnham BL, Chick WL. Modulation of glucose-induced insulin secretion from a rat clonal β-cell line. Endocrinology 127: 2779–2788, 1990. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-6-2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asfari M, Janjic D, Meda P, Li G, Halban PA, Wollheim CB. Establishment of 2-mercaptoethanol-dependent differentiated insulin-secreting cell lines. Endocrinology 130: 167–178, 1992. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.1.1370150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravassard P, Hazhouz Y, Pechberty S, Bricout-Neveu E, Armanet M, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R. A genetically engineered human pancreatic β cell line exhibiting glucose-inducible insulin secretion. J Clin Invest 121: 3589–3597, 2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI58447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benazra M, Lecomte M-J, Colace C, Müller A, Machado C, Pechberty S, Bricout-Neveu E, Grenier-Godard M, Solimena M, Scharfmann R, Czernichow P, Ravassard P. A human beta cell line with drug inducible excision of immortalizing transgenes. Mol Metab 4: 916–925, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scharfmann R, Pechberty S, Hazhouz Y, Bülow von M, Bricout-Neveu E, Grenier-Godard M, Guez F, Rachdi L, Lohmann M, Czernichow P, Ravassard P. Development of a conditionally immortalized human pancreatic β cell line. J Clin Invest 124: 2087–2098, 2014. doi: 10.1172/JCI72674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoo K, Bando H, Tabata Y. Enhanced survival and insulin secretion of insulinoma cell aggregates by incorporating gelatin hydrogel microspheres. Regen Ther 8: 29–37, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amin J, Ramachandran K, Williams SJ, Lee A, Novikova L, Stehno-Bittel L. A simple, reliable method for high-throughput screening for diabetes drugs using 3D β-cell spheroids. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 82: 83–89, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinohara M, Kimura H, Montagne K, Komori K, Fujii T, Sakai Y. Combination of microwell structures and direct oxygenation enables efficient and size-regulated aggregate formation of an insulin-secreting pancreatic β-cell line. Biotechnol Progress 30: 178–187, 2014. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lock LT, Laychock SG, Tzanakakis ES. Pseudoislets in stirred-suspension culture exhibit enhanced cell survival, propagation and insulin secretion. J Biotechnol 151: 278–286, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luther MJ, Hauge-Evans A, Souza KLA, Jörns A, Lenzen S, Persaud SJ, Jones PM. MIN6 β-cell–β-cell interactions influence insulin secretory responses to nutrients and non-nutrients. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 343: 99–104, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly C, Guo H, McCluskey JT, Flatt PR, McClenaghan NH. Comparison of insulin release from MIN6 pseudoislets and pancreatic islets of Langerhans reveals importance of homotypic cell interactions. Pancreas 39: 1016–1023, 2010. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181dafaa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka H, Tanaka S, Sekine K, Kita S, Okamura A, Takebe T, Zheng Y-W, Ueno Y, Tanaka J, Taniguchi H. The generation of pancreatic β-cell spheroids in a simulated microgravity culture system. Biomaterials 34: 5785–5791, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulze T, Morsi M, Brüning D, Schumacher K, Rustenbeck I. Different responses of mouse islets and MIN6 pseudo-islets to metabolic stimulation: a note of caution. Endocrine 51: 440–447, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0701-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB. Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 49: 424–430, 2000. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart NJ, Weber C, Papas KK, Limesand SW, Vagner J, Lynch RM. Multivalent activation of GLP-1 and sulfonylurea receptors modulates β-cell second-messenger signaling and insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 316: C48–C56, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00209.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chick WL, Warren S, Chute RN, Like AA, Lauris V, Kitchen KC. A transplantable insulinoma in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74: 628–632, 1977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gotoh M, Maki T, Satomi S, Porter J, Bonner-Weir S, O’Hara CJ, Monaco AP. Reproducible high yield of rat islets by stationary in vitro digestion following pancreatic ductal or portal venous collagenase injection. Transplantation 43: 725–730, 1987. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198705000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NIH CIT Consortium Chemistry Manufacturing Controls Monitoring Committee, NIH CIT Consortium. Purified human pancreatic islet—viability estimation of islet using fluorescent dyes (FDA/PI): standard operating procedure of the NIH Clinical Islet Transplantation Consortium. CellR4 Repair Replace Regen Reprogram 3: e1378, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papas KK, Pisania A, Wu H, Weir GC, Colton CK. A stirred microchamber for oxygen consumption rate measurements with pancreatic islets. Biotechnol Bioeng 98: 1071–1082, 2007. doi: 10.1002/bit.21486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rocheleau JV, Head WS, Piston DW. Quantitative NAD(P)H/flavoprotein autofluorescence imaging reveals metabolic mechanisms of pancreatic islet pyruvate response. J Biol Chem 279: 31780–31787, 2004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richmond KN, Burnite S, Lynch RM. Oxygen sensitivity of mitochondrial metabolic state in isolated skeletal and cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 273: C1613–C1622, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly AC, Camacho LE, Pendarvis K, Davenport HM, Steffens NR, Smith KE, Weber CS, Lynch RM, Papas KK, Limesand SW. Adrenergic receptor stimulation suppresses oxidative metabolism in isolated rat islets and Min6 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 473: 136–145, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Praz GA, Halban PA, Wollheim CB, Blondel B, Strauss AJ, Renold AE. Regulation of immunoreactive-insulin release from a rat cell line (RINm5F). Biochem J 210: 345–352, 1983. doi: 10.1042/bj2100345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wikstrom JD, Sereda SB, Stiles L, Elorza A, Allister EM, Neilson A, Ferrick DA, Wheeler MB, Shirihai OS. A novel high-throughput assay for islet respiration reveals uncoupling of rodent and human islets. PLoS One 7: e33023, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blacker TS, Duchen MR. Investigating mitochondrial redox state using NADH and NADPH autofluorescence. Free Radic Biol Med 100: 53–65, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haythorne E, Rohm M, van de Bunt M, Brereton MF, Tarasov AI, Blacker TS, Sachse G, Silva Dos Santos M, Terron Exposito R, Davis S, Baba O, Fischer R, Duchen MR, Rorsman P, MacRae JI, Ashcroft FM. Diabetes causes marked inhibition of mitochondrial metabolism in pancreatic β-cells. Nat Commun 10: 2474, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weegman BP, Essawy A, Nash P, Carlson AL, Voltzke KJ, Geng Z, Jahani M, Becker BB, Papas KK, Firpo MT. Nutrient regulation by continuous feeding for large-scale expansion of mammalian cells in spheroids. J Vis Exp 115: 52224, 2016. doi: 10.3791/52224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komatsu H, Kandeel F, Mullen Y. Impact of oxygen on pancreatic islet survival. Pancreas 47: 533–543, 2018. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suszynski TM, Avgoustiniatos ES, Papas KK. Oxygenation of the intraportally transplanted pancreatic islet. J Diabetes Res 2016: 7625947, 2016. doi: 10.1155/0016/7625947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papas KK, Colton CK, Nelson RA, Rozak PR, Avgoustiniatos ES, Scott WE, Wildey GM, Pisania A, Weir GC, Hering BJ. Human islet oxygen consumption rate and DNA measurements predict diabetes reversal in nude mice. Am J Transplant 7: 707–713, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitzmann JP, O'Gorman D, Kin T, Gruessner AC, Senior P, Imes S, Gruessner RW, Shapiro AMJ, Papas KK. Islet oxygen consumption rate dose predicts insulin independence for first clinical islet allotransplants. Transplant Proc 46: 1985–1988, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pepper AR, Hasilo CP, Melling CWJ, Mazzuca DM, Vilk G, Zou G, White DJG. The islet size to oxygen consumption ratio reliably predicts reversal of diabetes posttransplant. Cell Transplant 21: 2797–2804, 2012. doi: 10.3727/096368912X653273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cline GW, LePine RL, Papas KK, Kibbey RG, Shulman GI. 13C NMR isotopomer analysis of anaplerotic pathways in INS-1 cells. J Biol Chem 279: 44370–44375, 2004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cline GW, Pongratz RL, Zhao X, Papas KK. Rates of insulin secretion in INS-1 cells are enhanced by coupling to anaplerosis and Kreb’s cycle flux independent of ATP synthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 415: 30–35, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papas KK, Jarema MA. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion is not obligatorily linked to an increase in O2 consumption in βHC9 cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 275: E1100–E1106, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.6.E1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hellerström C. Oxygen consumption of isolated pancreatic islets of mice studied with the cartesian-diver micro-gasometer. Biochem J 98: 7C–9C, 1966. doi: 10.1042/bj0980007c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hutton JC, Malaisse WJ. Dynamics of O2 consumption in rat pancreatic islets. Diabetologia 18: 395–405, 1980. doi: 10.1007/BF00276821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramirez R, Rasschaert J, Sener A, Malaisse WJ. The coupling of metabolic to secretory events in pancreatic islets. Glucose-induced changes in mitochondrial redox state. Biochim Biophys Acta 1273: 263–267, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(95)00156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Marchi U, Thevenet J, Hermant A, Dioum E, Wiederkehr A. Calcium co-regulates oxidative metabolism and ATP synthase-dependent respiration in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem 289: 9182–9194, 2014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.513184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skrzypek K, Barrera YB, Groth T, Stamatialis D. Endothelial and beta cell composite aggregates for improved function of a bioartificial pancreas encapsulation device. Int J Artif Organs 41: 152–159, 2018. doi: 10.1177/0391398817752295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bowles AC, Ishahak MM, Glover SJ, Correa D, Agarwal A. Evaluating vascularization of heterotopic islet constructs for type 1 diabetes using an in vitro platform. Integr Biol (Camb) 11: 331–341, 2019. doi: 10.1093/intbio/zyz027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhi Z-L, Liu B, Jones PM, Pickup JC. Polysaccharide multilayer nanoencapsulation of insulin-producing β-cells grown as pseudoislets for potential cellular delivery of insulin. Biomacromolecules 11: 610–616, 2010. doi: 10.1021/bm901152k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hiscox AM, Stone AL, Limesand S, Hoying JB, Williams SK. An islet-stabilizing implant constructed using a preformed vasculature. Tissue Eng Part A 14: 433–440, 2008. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skelin M, Rupnik M, Cencic A. Pancreatic beta cell lines and their applications in diabetes mellitus research. ALTEX 27: 105–113, 2010. doi: 10.14573/altex.2010.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kutlu B, Burdick D, Baxter D, Rasschaert J, Flamez D, Eizirik DL, Welsh N, Goodman N, Hood L. Detailed transcriptome atlas of the pancreatic beta cell. BMC Med Genomics 2: 3–11, 2009. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]