Abstract

The reservoir host of Mokola virus (MOKV), a rabies-related lyssavirus species endemic to Africa, remains unknown. Only sporadic cases of MOKV have been reported since its first discovery in the late 1960s, which subsequently gave rise to various reservoir host hypotheses. One particular hypothesis focusing on non-volant small mammals (e.g. shrews, sengis and rodents) is buttressed by previous MOKV isolations from shrews (Crocidura sp.) and a single rodent (Lophuromys sikapusi). Although these cases were only once-off detections, it provided evidence of the first known lyssavirus species has an association with non-volant small mammals. To investigate further, retrospective surveillance was conducted in 575 small mammals collected from South Africa. Nucleic acid surveillance using a pan-lyssavirus quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay of 329 brain samples did not detect any lyssavirus ribonucleic acid (RNA). Serological surveillance using a micro-neutralisation test of 246 serum samples identified 36 serum samples that were positive for the presence of MOKV neutralising antibodies (VNAs). These serum samples were all collected from Gerbilliscus leucogaster (Bushveld gerbils) rodents from Meletse in Limpopo province (South Africa). Mokola virus infections in Limpopo province have never been reported before, and the high MOKV seropositivity of 87.80% in these gerbils may indicate a potential rodent reservoir.

Keywords: Bushveld gerbil, lyssavirus, Mokola, non-volant small mammal, rabies-related, reservoir, rodent, surveillance

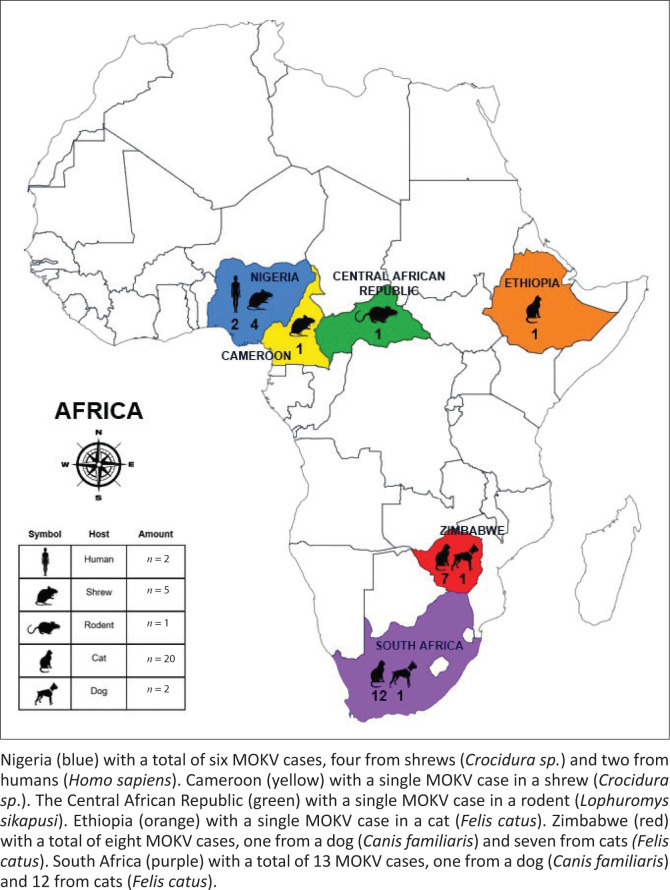

The Mokola virus (MOKV), a rabies-related lyssavirus, represents one of 17 recognised species within the Lyssavirus genus, all capable of causing a fatal encephalitic disease (Walker et al. 2018). The Mokola virus is exclusively endemic in Africa with only 30 sporadic cases reported since its discovery more than 50 years ago (Figure 1; Table 1) (Coertse et al. 2017; Kgaladi et al. 2013). The reservoir host of MOKV is still unknown, with spillover dead-end hosts such as domestic cats (Felis catus) and dogs (Canis familiaris), most commonly reported to be infected with MOKV. This has led to the hypothesis that the reservoir of MOKV might be a prey species that interacts with domesticated animals via a prey-to-predator pathway (Kgaladi et al. 2013). Non-volant small mammals (i.e. shrews, sengis and rodents) have been suggested as possible reservoir hosts considering that previous MOKV isolations were in shrews (Crocidura spp.), four in Nigeria and one in Cameroon (Causey et al. 1969; Kemp et al. 1972; Le Gonidec et al. 1978), and a single reported case in a rodent (Lophuromys sikapusi) in the Central African Republic (Saluzzo et al. 1984). To investigate further, nucleic acid and serological surveillance were retrospectively conducted, targeting non-volant small mammals from specific locations in South Africa.

FIGURE 1.

Geographical distribution of all reported Mokola virus cases (n = 30) in the African continent.

TABLE 1.

Summary of all reported Mokola virus cases in Africa.

| Date | Virus/Laboratory Reference Numbers | Host Species | Detection Material | Geographical Location | Reference‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria (n = 6) | |||||

| May 1968 | IbAn 26801† | Crocidura sp. (Shrew) | Organ pool (heart, lung, liver, spleen & kidney) | Ife Farm, Ibadan, Nigeria | Causey and Kemp (1968); Kemp et al. (1972) |

| May 1968 | IbAn 27157† | Crocidura sp. (Shrew) | Organ pool (heart, lung, liver, spleen & kidney) | Private residence, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria | Causey and Kemp (1968); Kemp et al. (1972) |

| July 1968 | IbAn 27377† RV4 |

Crocidura sp. (Shrew) | Organ pool (heart, lung, liver, spleen & kidney) | Mokola, Ibadan, Nigeria | Causey and Kemp (1968); Kemp et al. (1972) |

| August 1968 | IbAn 29777† | Homo sapiens (Human) | Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) | Inalende, Ibadan, Nigeria | Familusi and Moore (1972); Kemp et al. (1972) |

| December 1969 | IbAn 51715† | Crocidura sp. (Shrew) | Organ pool (liver & spleen) | Virus Research Laboratory, Ibadan, Nigeria | Causey and Kemp (1969); Kemp et al. (1972) |

| March 1971 | IbAn 56909† | Homo sapiens (Human) | Brain | Idikan, Ibadan, Nigeria | Familusi and Moore (1972); Kemp et al. (1972) |

| Cameroon (n = 1) | |||||

| January 1974 | An Y1307† RV39 86100CAM |

Crocidura sp. (Shrew) | Organ pool (brain, liver & spleen) | Nkol-Owona, Yaounde, Cameroon | Le Gonidec et al. (1978) |

| Central African Republic (n = 1) | |||||

| October 1981 | AnRB3247† RV40 86101RCA |

Lophuromys sikapusi (Rodent) | Brain | Botami, Bangui, Central African Republic | Saluzzo et al. (1984) |

| Ethiopia (n = 1) | |||||

| 1989–1990 | Eth-16† RA 133/82 RV610 |

Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | Mebatsion, Cox and Frost (1992) |

| Zimbabwe (n = 8) | |||||

| April 1981 | 12017† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Bulawayo, Zimbabwe | Foggin (1982); Foggin (1988) |

| May 1981 | 12245† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Bulawayo, Zimbabwe | Foggin (1982); Foggin (1988) |

| June 1981 | 12341† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Bulawayo, Zimbabwe | Foggin (1982); Foggin (1988) |

| August 1981 | 12574† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Bulawayo, Zimbabwe | Foggin (1982); Foggin (1988) |

| October 1981 | 12800† | Canis familiaris (Dog) | Brain | Bulawayo, Zimbabwe | Foggin (1982); Foggin (1988) |

| March 1982 | 13270† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Bulawayo, Zimbabwe | Foggin (1983); Foggin (1988) |

| April 1982 | 13371† Zim82 RV1035 |

Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Bulawayo, Zimbabwe | Foggin (1983); Foggin (1988) |

| November 1993 | 21846† RV1017 |

Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Selous, Zimbabwe | Bingham et al. (2001) |

| South Africa (n = 13) | |||||

| December 1970 | 700/70† V21.G3 V241 |

Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Umhlanga Rocks, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Meredith and Nel (1996); Nel et al. (2000) |

| July 1995 | 543/95† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Mdantsane, Eastern Cape, South Africa | Meredith and Nel (1996); Nel et al. (2000) |

| February 1996 | 112/96† RV1021 |

Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | East London, Eastern Cape, South Africa | Von Teichman et al. (1998); Nel et al. (2000) |

| May 1996 | 322/96† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Yellow Sands, Eastern Cape, South Africa | Von Teichman et al. (1998); Nel et al. (2000) |

| May 1997 | 252/97† V552.S3 |

Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Pinetown, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Von Teichman et al. (1998); Nel et al. (2000) |

| May 1997 | 229/97† V550.S3 |

Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Pinetown, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Von Teichman et al. (1998); Nel et al. (2000) |

| March 1998 | 071/98† V635.S3 RA361 |

Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Von Teichman et al. (1998); Nel et al. (2000 |

| June 2005 | 404/05† | Canis familiaris (Dog) | Brain | Nkomazi, Mpumalanga, South Africa | Sabeta et al. (2007) |

| March 2006 | 173/06† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Farm near East London, Eastern Cape, South Africa | Sabeta et al. (2007) |

| 2008 | 226/08† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa | Sabeta et al. (2010) |

| June 2012 | 12/458† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Coertse et al. (2017) |

| July 2012 | 12/604† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Coertse et al. (2017) |

| January 2014 | 14/024† | Felis catus (Cat) | Brain | Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Coertse et al. (2017) |

Sp., species; RV, rabies virus; IbAn, Ibadan.

, The original virus reference number as indicated in the reference article(s);

, References form part of Appendix 2.

Non-volant small mammals were captured and sampled in accordance with the field procedure guidelines of Sikes and Gannon (2011) during the period of 2015–2017 from two different sites in South Africa: Meletse area in Limpopo province (24.5914° S, 27.6258° E) and Secunda area in Mpumalanga Province (26.5158° S, 29.1914° E). All the species investigated were designated as of Least Concern by The International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species. Morphological species identification followed classifications by Meester et al. (1986), Newbery (1999), as well as Monadjem et al. (2015). Following morphological identification, animals were anesthetised with Isofor (Safeline Pharmaceuticals, South Africa), after which blood was collected by cardiac puncture (1% – 3% volume/body mass) in 0.8 mL MiniCollect serum separator tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Austria). Serum was separated from whole blood by centrifugation (Centrifuge 5418, Eppendorf, Germany) at 4300 g for 5 min and transferred to 2.0 mL Sarstedt tubes (Sarstedt Inc.). Animals that were not collected as voucher specimens were marked with a unique tattoo number near the base of their tail, and released back to their respective capture sites. Voucher specimens were euthanised with an overdose of Isofor, after which their organs were harvested (i.e. brain, tongue, salivary glands, heart, kidney, lungs, pectoral muscle, spleen, intestines, rectum and bladder) in 2.0 mL Sarstedt tubes for a broader pathogen surveillance study and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen until storage at –80 °C. Carcasses were placed in a 3 L PathoPak (Intelsius Solutions, United Kingdom [UK]) containing 80% ethanol and were submitted to Ditsong National Museum of Natural History and the Natural History Collection for Public Health and Economics for voucher-based morphological identification, and museum archiving.

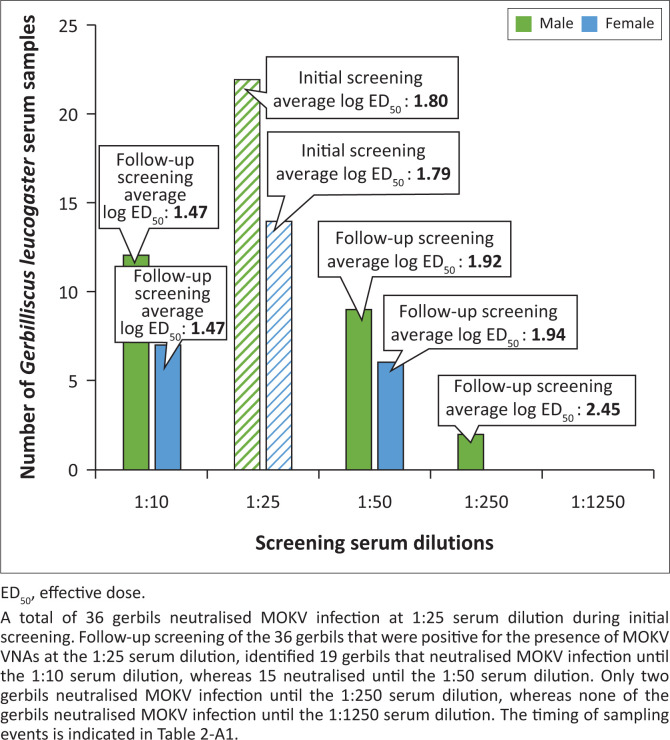

Total ribonucleic acids (RNAs) were extracted from brain samples (n = 329) (nine shrews, four sengis and 316 rodents) using TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen, United States [US]), followed by nucleic acid surveillance using a pan-lyssavirus quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay as previously described (Coertse et al. 2019). Serum samples (n = 246) (three shrews, four sengis and 239 rodents) were subjected to serological surveillance using a micro-neutralisation test as previously described (Smith & Gilbert 2017), during which MOKV 12/458 (2012, Felis catus, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa) (Coertse et al. 2017) was used as challenge virus. If a reduction or absence of fluorescence was observed at the 1:25 serum dilution during initial screening, the serum sample was subjected to follow-up screening (in duplicate) at 1:10, 1:50, 1:250 and 1:1250 serum dilutions. The 50% end-point (ED) neutralisation titre was calculated by the Reed and Muench method (1938) and considered positive for Mokola virus neutralising antibodies (MOKV VNAs) when they had a 50% ED neutralisation titre at a serum dilution of ≥ 25 (i.e. where ≤ 5 out of the 10 counted fields contain infected cells at the 1:25 serum dilution). If additional material was available, non-volant small mammals that tested positive for the presence of MOKV VNAs were subjected to genetic species identification with the Cytochrome B (CytB) barcoding PCR assay as previously described (Greenberg et al. 2012). Template deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) required for the barcoding assay was extracted from various biological sample types (such as blood, kidney, heart and pectoral tissue) using the Quick-DNA™ Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research, US).

All of the brain samples were negative for the presence of viral RNA with the pan-lyssavirus qRT-PCR assay (Appendix Table 1-A1). Negative results were expected as these animals were apparently healthy individuals and did not exhibit any visible signs of disease. An overall MOKV seropositivity of 87.80% (36 out of 41) was observed for the gerbils (Gerbilliscus leucogaster) tested from Meletse at the cut-off 1:25 serum dilution (Figure 2; Appendix Tables 1-A1, 2-A1, 3-A1 & 4-A1). The titre ranges for this rodent species were high when compared to another serological surveillance study conducted in Zimbabwe (Foggin 1988). Foggin identified MOKV VNAs in 5.63% (18 out of 320) of all rodents that were tested. An overall MOKV seropositivity of 17.57% (13 out of 74) was observed for gerbils which neutralised MOKV infection at various serum dilutions that ranged from 1:8, 1:16 to 1:32. None of the other MOKV serological surveillance studies have tested this rodent species for the presence of MOKV VNAs (Aghomo et al. 1990; Kemp et al. 1972; Nottidge, Omobowale & Oladiran 2007; Ogunkoya et al. 1990). Even though MOKV has been shown to cross-react in serological assays with other closely-related lyssaviruses (Kuzmin et al. 2008), cross-reactivity with other phylogroup II lyssaviruses was not investigated in this study.

FIGURE 2.

Graphical representation of the micro-neutralisation test results of the Gerbilliscus leucogaster serum samples from Meletse (n = 36).

Of the 36 gerbils showing MOKV seropositivity, only 28 were genetically identified with the CytB barcoding PCR assay (Table 2). The same identification was obtained from morphological examination of 24 voucher specimens (Table 2). Eight gerbils could not be identified to species level as they were released and no additional sample material was available. The Highveld gerbil, Gerbilliscus brantsii, is sympatric with G. leucogaster, however, based on known museum records, no G. brantsii has been caught at Meletse before (Rautenbach 1982) and these were, therefore, allocated to G. cf. leucogaster. The variability observed in the per cent identity (i.e. 83.78% – 100.00%) between the individual gerbils is expected since previous molecular characterisation assays performed on the Gerbilliscus genus have recorded intra-species genetic variation that range from 1% to 20% (Aghová et al. 2017; Colangelo et al. 2007).

TABLE 2.

Genetic and morphological species identification and voucher information for all Gerbilliscus leucogaster serum samples from Meletse, Limpopo province that were positive for the presence of Mokola virus neutralising antibodies.

| UP reference number | Sample information |

Museum information† |

Genetic identification information‡ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original morphological identification (Field) | Museum number | Morphological identification confirmation | PCR assay | DNA source | Query cover (%) | Per cent (%) identity | GenBank accession number§ | Genetic identification (BLAST result) | |

| UP4962 | Gerbilliscus sp. | TM49197 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Pectoral | 99 | 97.78 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12086 | Gerbilliscus sp. | TM49248 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 100 | 99.79 | AJ875294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12133 | Gerbilliscus sp. | TM49251 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 66 | 84.33 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12166 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | TM49259 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Heart | 98 | 94.85 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12183 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| UP12185 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | TM50540 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Rectum | 86 | 98.31 | AJ875294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12187 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | TM50541 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Pectoral | 100 | 99.57 | AJ875294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12193 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | TM50542 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Lung | 97 | 93.33 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12194 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | NHCPHE_MAM-20 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 100 | 99.60 | KM454057 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12195 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | NHCPHE_MAM-21 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 100 | 95.10 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12196 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Blood | 100 | 89.29 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12197 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | NHCPHE_MAM-22 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 100 | 96.59 | KM454057 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12202 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | NHCPHE_MAM-23 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 96 | 99.16 | AJ875294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12207 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | TM50543 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Lung | 100 | 93.40 | KM453987 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12208 | Gerbilliscus sp. | NHCPHE_MAM-3 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 99 | 86.76 | KM453992 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12221 | Gerbilliscus sp. | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Blood | 100 | 99.57 | AJ875294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12223 | Gerbilliscus sp. | TM50544 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Pectoral | 100 | 97.23 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12246 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | TM50545 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Pectoral | 100 | 97.87 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12259 | Gerbilliscus sp. | TM50546 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Pectoral | 100 | 100.00 | AJ875294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12296 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | NHCPHE_MAM-24 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Heart | 66 | 83.78 | AJ865294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12297 | Gerbilliscus sp. | NHCPHE_MAM-5 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 100 | 90.71 | KM453986 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12303 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | TM50547 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Pectoral | 100 | 99.15 | AJ875294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12307 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | TM50548 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 98 | 85.41 | KM453992 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12350 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| UP12354 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| UP12373 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Blood | 100 | 94.03 | KM453987 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12426 | Gerbilliscus sp. | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Blood | 100 | 94.24 | KM454060 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12431 | Gerbilliscus sp. | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| UP12457 | Gerbilliscus sp. | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| UP12517 | Gerbilliscus sp. | NHCPHE_MAM-25 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Pectoral | 100 | 99.57 | AJ875294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12518 | Gerbilliscus sp. | NHCPHE_MAM-26 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 96 | 97.66 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12524 | Gerbilliscus sp. | TM50549 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Heart | 81 | 97.10 | AJ875294 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12526 | Gerbilliscus sp. | TM50550 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | CytB | Kidney | 97 | 97.45 | AJ875295 | Gerbilliscus leucogaster |

| UP12539 | Gerbilliscus sp. | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| UP12543 | Gerbilliscus sp. | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| UP12553 | Gerbilliscus sp. | N/A | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | - | - | - | - | - | - |

UP, University of Pretoria; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; N/A, not available; TM, Transvaal museum; NHCPHE_MAM, Natural History Collection of Public Health and Economics; CytB, Cytochrome B; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; BLAST, Basic Local Alignment Search tool.

, Museum information (i.e. museum number & morphological identification) for vouchers in Ditsong National Museum of Natural History (TM) and Natural History Collection of Public Health and Economics (NHCPHE_MAM), N/A refers to not available because no voucher was taken;

, Genetic identification information: (1) PCR assay refers to the molecular barcoding assay that was used to determine the genetic identity of the rodent – Cytochrome B (CytB); (2) DNA source refers to the material that was used to extract DNA from for the PCR assay; (3) Query cover refers to how much the submitted sequence (i.e. the query sequence) is covered by the target sequence; (4) Per cent identity refers to the similarity of the query sequence to the target sequence; (5) GenBank accession number refers to GenBank’s reference for the target sequence; (6) BLAST results refer to the genetic identity (i.e. genus and species name) of the target sequence’s organism;

, The genus and species names associated with the listed GenBank accession numbers from the BLAST results refer to Tatera leucogaster. T. leucogaster underwent a taxonomic name change in 2005 and is currently referred to as Gerbilliscus leucogaster.

Members of the Gerbilliscus genus are nocturnal and terrestrial, exhibit no sexual dimorphism (Skinner & Chimimba 2005) and occupy simple to complex, deep burrows (i.e. warrens) (De Graaff 1981; Granjon & Dempster 2013). They are physiologically, morphologically and behaviourally adapted to live in arid climates (Granjon & Dempster 2013; Monadjem et al. 2015). Gerbilliscus leucogaster, however, is less arid adapted and can be found along rivers and drainage lines in open grasslands and wooded savannas (Dempster 2013; Monadjem et al. 2015). The breeding pattern and social organisation of G. leucogaster rodents are not well-understood, however, studies have reported a communal nature (De Graaff 1981; Smithers 1971) with burrows being occupied by a pair (Skinner & Chimimba 2005) and some warrens housing families or several adults (Choate 1972). The ecological nature of Bushveld gerbils may potentially be the reason why this specific rodent species are more likely to be MOKV seropositive compared to solitary rodent species belonging to the Steatomys and Rhabdomys genera occurring at Meletse.

More nucleic acid and serological surveillance studies in non-volant small mammal populations are required to obtain a better understanding of MOKV distribution, prevalence and its potential reservoir species. Brain and serum samples in this study were collected from seemingly healthy small mammals in areas that do not coincide with areas where previous MOKV cases have been reported in South Africa. Surveillance should be expanded to areas where MOKV spillover infections in cats and dogs have previously been reported. Furthermore, because lyssavirus distribution and dynamics might be influenced by seasonality, surveillance efforts should also include samples that were collected in different seasons and over multiple years. This expansion, together with representative sample sizes of certain non-volant small mammal species, will collectively increase the possibility of identifying more of these animals that are infected or that have previously been exposed to MOKV.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ contributions

W.C.M. performed all experiments associated with this study which forms part of his M.Sc. Medical Virology degree. J.C. and W.M. provided academic guidance and supervised the overall process and operations of this study. T.K., M.K. and L.H.S. assisted with non-volant small mammal sample collection and species identification in the field. T.K. provided museum information from the Ditsong National Museum of Natural History. All authors contributed equally to the construction of this research communication.

Ethical considerations

This study formed part of a larger surveillance programme of the Bio-surveillance and Ecology of Emerging Zoonoses Research Group in the Centre for Viral Zoonoses that focuses on zoonotic pathogens in bats and non-volant small mammals. The overall research had animal ethical clearance from the University of Pretoria’s Animal Ethics Committee (AEC) (principal investigator: W.M.; project reference number: EC071-15) and had permission to do research in terms of Section 20 of the Animal Diseases Act of 1984 (Act No. 35 of 1984) from the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development (DALRRD) (Project Name: Epidemiology of zoonotic pathogens in rodents, shrews and sengis in Southern Africa; project reference number: 12/11/1/1/8). Sampling permits were obtained from Limpopo’s Department of Economic Development, Environment and Tourism (ZA/LP/73972 [2016–2017] and ZA/LP/83642 [2017–2018]) and Mpumalanga’s Tourism and Parks Agency (MPB.5583 [2017]). The M.Sc. Committee from the University of Pretoria’s School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences approved the protocol of this research project (Project Reference Number: 13057368). Individual animal ethical clearance (Principal Investigator: WM.; Project Reference Number: H008-18), as well as research ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Pretoria’s AEC and Research Ethics Committee (Project Reference Number: 426/2018).

Funding information

This study was funded by the South African Research Chair in Infectious Diseases of Animal (Zoonoses) from the National Research Foundation of the Department of Science and Innovation, W.M. (UID98339), as well as additional grants awarded to W.M. by the NRF (UID92524, UID85756 and UID91496). The National Research Foundation for funding the equipment based at the DNA Sanger Sequencing Facility in the Faculty of Natural of Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria (UID78566) and the Poliomyelitis Research Foundation.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Disclaimer

The contents of this research communication are solely the responsibility of the authors. The opinions, findings and conclusions expressed do not necessarily reflect the official view of the National Research Foundation.

Appendix 1

TABLE 1-A1.

Non-volant small mammal species included in the surveillance of Mokola virus in South Africa.

| Non-volant small mammal type | Non-volant small mammal species | Brain samples |

Serum samples |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount tested | Amount positive | Amount tested | Amount positive | ||

| Meletse, Limpopo, South Africa (n = 473) | |||||

| Shrews (n = 9) | Crocidura hirta | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Crocidura maquassiensis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Suncus lixus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sengis (n = 8) | Elephantulus brachyrhynchus | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Rodents (n = 457) | Acomys selousi | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Aethomys sp. | 1 | 0 | 16 | 0 | |

| Aethomys ineptus | 30 | 0 | 23 | 0 | |

| Aethomys chrysophilus | 20 | 0 | 16 | 0 | |

| Gerbilliscus sp. | 1 | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| Gerbilliscus leucogaster | 33 | 0 | 36 | 31 | |

| Graphiurus murinus | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Lemniscomys rosalia | 9 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

| Mastomys coucha | 45 | 0 | 23 | 0 | |

| Mastomys natalensis s.l. | 13 | 0 | 12 | 0 | |

| Micaelamys sp. | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Micaelamys namaquensis | 11 | 0 | 10 | 0 | |

| Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 29 | 0 | 12 | 0 | |

| Rattus sp. | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Saccostomus campestris | 19 | 0 | 19 | 0 | |

| Steatomys sp. | 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Steatomys pratensis | 21 | 0 | 16 | 0 | |

| Total amount of samples tested for Meletse | 262 | 0 | 211 | 36 | |

| Secunda, Mpumalanga, South Africa (n = 102) | |||||

| Shrews (n = 3) | Crocidura sp. | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Suncus sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rodents (n = 101) | Mastomys sp. | 40 | 0 | 26 | 0 |

| Mastomys natalensis | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Rhabdomys sp. | 21 | 0 | 6 | 0 | |

| Total amount of samples tested for Secunda | 67 | 0 | 35 | 0 | |

Note: Positive results are indicated in bold.

Sp., species.

TABLE 2-A1.

Sampling event details of collected Gerbilliscus leucogaster serum samples from Meletse, Limpopo province and their seropositivity.

| Sampling (Month & year) | Associated season† | Number of serum samples collected | Number of serum samples positive for MOKV VNAs | Percentage | Seropositivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 2015 | Summer | 1 | 1 | 100.00 | 1/1 |

| January 2016 | Summer | 1 | 0 | 0.00 | 0/1 |

| June 2016 | Winter | 1 | 1 | 100.00 | 1/1 |

| September 2016 | Spring | 1 | 1 | 100.00 | 1/1 |

| November 2016 | Spring | 1 | 1 | 100.00 | 1/1 |

| March 2017 | Autumn/Fall | 17 | 15 | 88.24 | 15/17 |

| May 2017 | Autumn/Fall | 9 | 7 | 77.78 | 7/9 |

| August 2017 | Winter | 3 | 3 | 100.00 | 3/3 |

| November 2017 | Spring | 7 | 7 | 100.00 | 100/100 |

|

| |||||

| Total | 41 | 36 | 87.80% | 36/41 | |

MOKV VNAs, Mokola virus neutralising antibodies.

, Season delineation in South Africa: (1) Summer, 01 December to 28/29 February; (2) Autumn/Fall, 01 March to 31 May; (3) Winter, 01 June to 31 August; (4) Spring, 01 September to 30 November.

TABLE 3-A1.

The 50% end-point neutralisation titres of all Gerbilliscus leucogaster serum samples from Meletse, Limpopo province that were positive for the presence of Mokola virus neutralising antibodies.

| Reference number | Serum sample information |

Initial screening‡ |

Follow-up screening‡ |

MOKV VNA titre | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample collection date | Sex | 1:10 (i) | 1:25 (i) | 1:10 (f) | 1:25 (f) | 1:10 (i) | 1:50 (i) | 1:250 (i) | 1:1250 (i) | Log ED50§ (i) | 1:10 (f) | 1:50 (f) | 1:250 (f) | 1:1250 (f) | Log ED50§ (f) | Average Log ED50 ± s.d.¶ | |

| UP4962† | 26 Feb 2015 | M | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 1.59 | 1 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 1.53 | 1.56 ± 0.03 |

| UP12086† | 08 June 2016 | M | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 1.83 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 1.76 | 1.80 ± 0.04 |

| UP12133† | 06 Sept. 2016 | M | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 1.53 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 1.48 | 1.51 ± 0.03 |

| UP12166† | 09 Nov. 2016 | M | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 2.17 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 2.05 | 2.11 ± 0.06 |

| UP12183 | 27 Mar. 2017 | F | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 1.92 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 1.77 | 1.85 ± 0.08 |

| UP12185† | 27 Mar. 2017 | F | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 1.97 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 1.92 | 1.95 ± 0.03 |

| UP12187† | 27 Mar. 2017 | F | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 1.40 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 1.58 | 1.49 ± 0.09 |

| UP12193† | 28 Mar. 2017 | M | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 2.10 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 1.92 | 2.01 ± 0.09 |

| UP12194† | 28 Mar. 2017 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 2.05 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 2.05 | 2.05 |

| UP12195† | 28 Mar. 2017 | M | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 2.05 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 2.05 | 2.05 |

| UP12196†† | 28 Mar. 2017 | F | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| UP12197† | 28 Mar. 2017 | M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 1.83 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 1.87 | 1.85 ± 0.02 |

| UP12202† | 28 Mar. 2017 | F | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 1.40 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 1.40 | 1.40 |

| UP12207† | 28 Mar. 2017 | M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 2.46 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 2.51 | 2.49 ± 0.02 |

| UP12208† | 28 Mar. 2017 | F | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 1.50 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 1.44 | 1.47 ± 0.03 |

| UP12221 | 29 Mar. 2017 | F | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 1.64 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 1.50 | 1.57 ± 0.07 |

| UP12223† | 29 Mar. 2017 | M | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 1.98 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 1.76 | 1.87 ± 0.11 |

| UP12246† | 30 Mar. 2017 | M | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 1.44 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 1.44 | 1.44 |

| UP12259† | 31 Mar. 2017 | F | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 1.44 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 1.44 | 1.44 |

| UP12296† | 16-May-2017 | M | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 1.45 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 1.35 | 1.40 ± 0.05 |

| UP12297† | 16 May 2017 | F | 1 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 1.50 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| UP12303† | 16 May 2017 | F | 2 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 1.45 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 1.35 | 1.40 ± 0.05 |

| UP12307† | 16 May 2017 | F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 2.17 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 2.05 | 2.11 ± 0.06 |

| UP12350 | 18 May 2017 | M | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 1.45 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 1.40 | 1.42 ± 0.03 |

| UP12354 | 18 May 2017 | F | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 1.83 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 1.77 | 1.80 ± 0.03 |

UP, University of Pretoria; MOKV VNA, Mokola virus neutralising antibodies ; ED50, effective dose; s.d., standard deviation; F, female; M, male.

, Small non-volant mammal individuals that were collected as voucher specimens and whose brains were negative for the presence of MOKV RNA. Animal ethics clearance was obtained from the University of Pretoria’s Animal Ethics Committee (Reference Numbers: EC071-15 & H008-18);

, Results for the 1:10, 1:25, 1:50, 1:250 & 1:1250 serum dilutions are recorded as a number that represents the number of fields (out of a total of 10) that contain MOKV 12/458 infected cells for both initial (i) and duplicate (f) rounds of the micro-neutralisation test;

, The log10 50% end-point (ED) neutralisation titre for each serum sample as calculated by Reed and Muench (1938);

, The average log10 50% ED neutralisation titre, together with the standard deviation (s.d.) for each serum sample as calculated by Reed and Muench (1938);

, Follow-up screening could not be completed as the serum sample was depleted during initial screening.

TABLE 4-A1.

Micro-neutralisation test results of all non-volant small mammal serum samples that tested negative for the presence of Mokola virus neutralising antibodies.

| Reference number | Serum sample information |

Initial screening† |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample collection date | Non-volant small mammal type | Non-volant small mammal species | 1:10 (i) | 1:25 (i) | 1:10 (f) | 1:25 (f) | |

| Meletse, Limpopo, South Africa (n = 211) | |||||||

| 4961 | 26 Feb. 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 4963 | 26 Feb. 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 4967 | 27 Feb. 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 4968 | 27 Feb. 2015 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 7 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 4969 | 27 Feb. 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 7 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 5011 | 03 Mar. 2015 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5012 | 03 Mar. 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 7 | 9 | 7 | 10 |

| 5015 | 04 Mar. 2015 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5017 | 05 Mar. 2015 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5352 | 12 May 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 5353 | 12 May 2015 | Sengi | Elephantulus brachyrhynchus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5354 | 12 May 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5355 | 12 May 2015 | Sengi | Elephantulus brachyrhynchus | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5356 | 12 May 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 5525 | 22 July 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 8 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 5527 | 23 July 2015 | Shrew | Crocidura maquassiensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5528 | 24 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 5529 | 24 July 2015 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5934 | 15 Sept. 2015 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 5935 | 15 Sept. 2015 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5936 | 15 Sept. 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 5939 | 17 Sept. 2015 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 9 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 12001 | 10 Nov. 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12003 | 11 Nov. 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12004 | 11 Nov. 2015 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12005 | 12 Nov. 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 5 | 9 | 6 | 10 |

| 12006 | 13 Nov. 2015 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12007 | 13 Nov. 2015 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12010 | 19 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12011 | 19 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12012 | 19 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12018 | 20 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12019 | 20 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12020 | 20 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12023 | 20 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12062 | 05 Apr. 2016 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 12065 | 06 Apr. 2016 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12066 | 06 Apr. 2016 | Rodent | Graphiurus murinus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12067 | 06 Apr. 2016 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12075 | 07 June 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12081 | 07 June 2016 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 2 | 8 | 2 | 8 |

| 12082 | 07 June 2016 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12083 | 07 June 2016 | Rodent | Acomys selousi | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12084 | 08 June 2016 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 8 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12085 | 08 June 2016 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12087 | 08 June 2016 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12088 | 09 June 2016 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12132 | 06 Sept. 2016 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 12134 | 06 Sept. 2016 | Rodent | Micaelamys sp. | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12140 | 07 Sept. 2016 | Rodent | Micaelamys sp. | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 12142 | 07 Sept. 2016 | Sengi | Elephantulus brachyrhynchus | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 12143 | 08 Sept. 2016 | Rodent | Micaelamys sp. | 8 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 12145 | 09 Sept. 2016 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12146 | 09 Sept. 2016 | Rodent | Acomys selousi | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12147 | 09 Sept. 2016 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12148 | 09 Sept. 2016 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12149 | 09 Sept. 2016 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12154 | 08 Nov. 2016 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12157 | 08 Nov. 2016 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12159 | 09 Nov. 2016 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12167 | 09 Nov. 2016 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 12168 | 10 Nov. 2016 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 8 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 12169 | 10 Nov. 2016 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12170 | 10 Nov. 2016 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 8 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| 12171 | 11 Nov. 2016 | Rodent | Acomys spp. | 9 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 12176 | 07 Feb. 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 3 | 9 | 3 | 10 |

| 12177 | 08 Feb. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 9 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| 12178 | 08 Feb. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 6 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| 12179 | 08 Feb. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 6 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

| 12180 | 09 Feb. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12181 | 09 Feb. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12184 | 27 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | 3 | 6 | 2 | 6 |

| 12188 | 27 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 12189 | 27 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 7 | 10 | 6 | 9 |

| 12190 | 27 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12191 | 27 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12192 | 28 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12200 | 28 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | 4 | 7 | 5 | 7 |

| 12201 | 28 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12203 | 28 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 6 | 9 | 6 | 10 |

| 12204 | 28 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 7 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 12205 | 28 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12206 | 28 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 5 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| 12209 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 8 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| 12210 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12211 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 9 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 12212 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys chrysophilus | 8 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12213 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Shrew | Crocidura hirta | 9 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| 12215 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 7 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| 12216 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12217 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 8 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| 12218 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 8 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 12219 | 29 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 8 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 12236 | 30 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 9 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 12237 | 30 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12238 | 30 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 7 | 10 | 6 | 10 |

| 12240 | 30 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12242 | 30 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 9 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| 12244 | 30 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12248 | 30 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12256 | 31 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Graphiurus murinus | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12258 | 31 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12260 | 31 Mar. 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys pratensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12285 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| 12289 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12291 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12292 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12294 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 8 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 12295 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12298 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12299 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12300 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12301 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12302 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12304 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12305 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Lemniscomys rosalia | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12306 | 16 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12311 | 17 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12319 | 17 May 2017 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12320 | 17 May 2017 | Rodent | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | 1 | 6 | 2 | 7 |

| 12321 | 17 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12324 | 17 May 2017 | Rodent | Gerbilliscus leucogaster | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12329 | 17 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12331 | 17 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12332 | 17 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12348 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12349 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12356 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12365 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12366 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12367 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 7 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 12374 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12375 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12376 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12377 | 19 May 2017 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12378 | 18 May 2017 | Rodent | Steatomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12380 | 19 May 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12381 | 19 May 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12394 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 6 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| 12395 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12405 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12406 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12409 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12414 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Sengi | Elephantulus brachyrhynchus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12422 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12423 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12428 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Lemniscomys rosalia | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12434 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12435 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12438 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12442 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12443 | 29 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Lemniscomys rosalia | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12447 | 30 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12449 | 30 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12452 | 30 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12453 | 30 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12458 | 30 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12468 | 30 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12474 | 31 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12475 | 31 Aug. 2017 | Rodent | Lemniscomys rosalia | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12515 | 21 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12516 | 21 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Lemniscomys rosalia | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12519 | 21 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12520 | 21 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Lemniscomys rosalia | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12521 | 21 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12525 | 21 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12538 | 21 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Lemniscomys rosalia | 8 | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| 12547 | 23 Nov. 2017 | Shrew | Crocidura hirta | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12549 | 23 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12552 | 23 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Aethomys ineptus | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12556 | 23 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Micaelamys namaquensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12557 | 23 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 7 | 10 | 6 | 10 |

| 12558 | 23 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Saccostomus campestris | 6 | 10 | 6 | 10 |

| 12562 | 24 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Mus (Nannomys) minutoides | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12563 | 24 Nov. 2017 | Rodent | Mastomys coucha | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Secunda, Mpumalanga, South Africa (n = 35) | |||||||

| 5532 | 30 June 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| 5552 | 01 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5553 | 01 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| 5566 | 02 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 5567 | 02 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5568 | 02 July 2015 | Rodent | Rhabdomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5569 | 02 July 2015 | Rodent | Rhabdomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5570 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 5571 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 5572 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Rhabdomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5573 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5574 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5575 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Rhabdomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 5576 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Rhabdomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5577 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5580 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5581 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 |

| 5582 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 5584 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5585 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 |

| 5586 | 03 July 2015 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12025 | 26 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| 12026 | 26 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12027 | 26 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys natalensis | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12028 | 27 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| 12029 | 27 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12030 | 27 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12031 | 27 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Rhabdomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12032 | 27 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 5 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| 12034 | 27 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12035 | 28 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 8 | 10 | 3 | 10 |

| 12036 | 28 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12037 | 28 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12038 | 28 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12050 | 29 Jan. 2016 | Rodent | Mastomys sp. | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

Sp., species.

, Results for the 1:10 and 1:25 serum dilutions are recorded as a number that represents the number of fields (out of a total of 10) that contain MOKV 12/458 infected cells for both initial (i) and duplicate (f) rounds of the micro-neutralisation test.

Appendix 2

Additional References

- Bingham, J., Javangwe, S., Sabeta, C.T., Wandeler, A.I. & Nel, L.H., 2001, ‘Report of isolations of unusual lyssaviruses (rabies and Mokola virus) identified retrospectively from Zimbabwe’, Journal of the South African Veterinary Association 72(2), 92–94. 10.4102/jsava.v72i2.624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causey, O.R. & Kemp, G.E., 1968, ‘Surveillance and study of viral infections of vertebrates in Nigeria’, Nigerian Journal of Science 2, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Familusi, J.B. & Moore, D.L., 1972, ‘Isolation of a rabies-related virus from the cerebrospinal fluid of a child with “aseptic meningitis”’, African Journal of Medical Sciences 3(1), 93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foggin, C.M., 1982, ‘Atypical rabies virus in cats and a dog in Zimbabwe’, Veterinary Record 110(14), 338–338. 10.1136/vr.110.14.338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foggin, C.M., 1983, ‘Mokola virus infection in cats and a dog in Zimbabwe’, The Veterinary Record 113(5), 115. 10.1136/vr.113.5.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebatsion, T., Cox, J.H. & Frost, J.W., 1992, ‘Isolation and characterization of 115 street rabies virus isolates from Ethiopia by using monoclonal antibodies: Identification of 2 isolates as Mokola and Lagos bat viruses’, Journal of Infectious Diseases 166(5), 972–977. 10.1093/infdis/166.5.972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, C.D. & Nel, L.H., 1996, ‘Further isolation of Mokola virus in South Africa’, The Veterinary Record 138(5), 119–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nel, L., Jacobs, J., Jaftha, J., Von Teichman, B. & Bingham, J., 2000, ‘New cases of Mokola virus infection in South Africa: A genotypic comparison of Southern African virus isolates’, Virus Genes 20(2), 103–106. 10.1023/A:1008120511752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeta, C.T., Blumberg, L., Miyen, J., Mohale, D., Shumba, W. & Wandeler, A., 2010, ‘Mokola virus involved in a human contact (South Africa)’, FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology 58(1), 85–90. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00609.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeta, C.T., Markotter, W., Mohale, D.K., Shumba, W., Wandeler, A.I. & Nel, L.H., 2007, ‘Mokola virus in domestic mammals, South Africa’, Emerging Infectious Diseases 13(9), 1371. 10.3201/eid1309.070466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Teichman, B.F., De Koker, W.C., Bosch, S.J.E., Bishop, G.C., Meredith, C.D. & Bingham, J., 1998, ‘Mokola virus infection: Description of recent South African cases and a review of the virus epidemiology: Case report’, Journal of the South African Veterinary Association 69(4), 169–171. 10.4102/jsava.v69i4.847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

How to cite this article: McMahon, W.C., Coertse, J., Kearney, T., Keith, M., Swanepoel, L.H. & Markotter, W., 2021, ‘Surveillance of the rabies-related lyssavirus, Mokola in non-volant small mammals in South Africa’, Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 88(1), a1911. https://doi.org/10.4102/ojvr.v88i1.1911

References

- Aghomo, H.O., Tomori, O., Oduye, O.O. & Rupprecht, C.E., 1990, ‘Detection of Mokola virus neutralising antibodies in Nigerian dogs’, Research in Veterinary Science 48(2), 264. 10.1016/S0034-5288(18)31005-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghová, T., Šumbera, R., Piálek, L., Mikula, O., McDonough, M.M., Lavrenchenko, L.A. et al. , 2017, ‘Multilocus phylogeny of East African gerbils (Rodentia, Gerbilliscus) illuminates the history of the Somali-Masai savanna’, Journal of Biogeography 44(10), 2295–2307. 10.1111/jbi.13017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Causey, O.R., Kemp, G.E., Madbouly, M.H. & Lee, V.H., 1969, ‘Arbovirus surveillance in Nigeria, 1964–1967’, Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique 62(2), 249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choate, T.S., 1972, ‘Behavioural studies on some Rhodesian rodents’, African Zoology 7(1), 103–118. 10.1080/00445096.1972.11447433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coertse, J., Markotter, W., Le Roux, K., Stewart, D., Sabeta, C.T. & Nel, L.H., 2017, ‘New isolations of the rabies-related Mokola virus from South Africa’, BMC Veterinary Research 13(1), 37. 10.1186/s12917-017-0948-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coertse, J., Weyer, J., Nel, L.H. & Markotter, W., 2019, ‘Reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid detection of canine associated rabies virus in Africa’, PLoS One 14(7), e0219292. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo, P., Granjon, L., Taylor, P.J. & Corti, M., 2007, ‘Evolutionary systematics in African gerbilline rodents of the genus Gerbilliscus: Inference from mitochondrial genes’, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 42(3), 797–806. 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Graaff, G., 1981, The rodents of southern Africa: Notes on their identification, distribution, ecology, and taxonomy, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster, E.R., 2013, ‘Gerbilliscus leucogaster’, Mammals of Africa 3, 279–281. [Google Scholar]

- Foggin, C.M., 1988, ‘Rabies and rabies-related viruses in Zimbabwe: Historical, virological and ecological aspects’, PhD thesis, University of Zimbabwe, Harare. [Google Scholar]

- Granjon, L. & Dempster, E.R., 2013, ‘Genus Gerbilliscus gerbils’, Mammals of Africa 3, 268–270. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.A., DiMenna, M.A., Hanelt, B. & Hofkin, B.V., 2012, ‘Analysis of post-blood meal flight distances in mosquitoes utilizing zoo animal blood meals’, Journal of Vector Ecology 37(1), 83–89. 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2012.00203.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, G.E., Causey, O.R., Moore, D.L., Odelola, A. & Fabiyi, A., 1972, ‘Mokola virus’, The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 21(3), 356–359. 10.4269/ajtmh.1972.21.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kgaladi, J., Wright, N., Coertse, J., Markotter, W., Marston, D., Fooks, A.R. et al. , 2013, ‘Diversity and epidemiology of Mokola virus’, PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 7(10), e2511. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin, I.V., Niezgoda, M., Franka, R., Agwanda, B., Markotter, W., Beagley, J.C. et al. , 2008, ‘Lagos bat virus in Kenya’, Journal of Clinical Microbiology 46(4), 1451–1461. 10.1128/JCM.00016-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gonidec, G., Rickenbach, A., Robin, Y. & Heme, G., 1978, ‘Isolement d’une souche de virus Mokola au Cameroun’, Annales des Microbiologie (Institute Pasteur) 129(A), 245–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meester, J.A.J., Rautenbach, I.L., Dippenaar, N.J. & Baker, C.M., 1986, ‘Classification of Southern African mammals’, Transvaal Museum Monograph 5(1), 1–359. [Google Scholar]

- Monadjem, A., Taylor, P.J., Denys, C. & Cotterill, F.P., 2015, Rodents of sub-Saharan Africa: A biogeographic and taxonomic synthesis, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- Newbery, C.H., 1999, ‘A key to the Soricidae, Macroscelididae, Gliridae and Muridae of Gauteng, North West Province, Mpumalanga and the Northern province, South Africa’, Koedoe 42(1), 51–55. 10.4102/koedoe.v42i1.221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nottidge, H.O., Omobowale, T.O. & Oladiran, O.O., 2007, ‘Mokola virus antibodies in humans, dogs, cats, cattle, sheep, and goats in Nigeria’, International Journal of Applied Research in Veterinary Medicine 5(3), 105. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunkoya, A.B., Beran, G.W., Umoh, J.U., Gomwalk, N.E. & Abdulkadir, I.A., 1990, ‘Serological evidence of infection of dogs and man in Nigeria by lyssaviruses (family Rhabdoviridae)’, Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 84(6), 842–845. 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90103-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautenbach, I.L., 1982, Mammals of the Transvaal, Ecoplan monograph no. 1:1–211, Transvaal Museum, Pretoria. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, L.J. & Muench, H., 1938, ‘A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints’, American Journal of Epidemiology 27(3), 493–497. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saluzzo, J.F., Rollin, P.E., Dauguet, C., Digoutte, J.P., Georges, A.J. & Sureau, P., 1984, ‘Premier isolement du virus Mokola à partir d’un rongeur (Lophuromys sikapusi)’, Annales de l’Institut Pasteur/Virologie 135(1), 57–66. 10.1016/S0769-2617(84)80039-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sikes, R.S. & Gannon, W.L., 2011, ‘Guidelines of the American society of mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research’, Journal of Mammalogy 92(1), 235–253. 10.1644/10-MAMM-F-355.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, J.D. & Chimimba, C.T., 2005, The mammals of the Southern African sub-region, Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Smithers, R.H.N., 1971, A checklist of the mammals of Botswana, Trustees of the National Museum of Rhodesia, Salisbury. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.G. & Gilbert, A.T., 2017, ‘Comparison of a micro-neutralization test with the rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test for measuring rabies virus neutralizing antibodies’, Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2(3), 24. 10.3390/tropicalmed2030024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.J., Breyta, R., Blasdell, K.R., Calisher, C.H., Dietzgen, R.G., Fooks, A.R. et al. , 2018, ‘Rhabdoviridaee’, in Kuhn J.H. & Siddel S.G. (eds.), ICTV Report Negative-sense RNA viruses, Journal of Gen eral Virology, 99, 447–448. viewed 24 May 2020, from https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_online_report/negative-sense-rna-viruses/w/rhabdoviridae [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.