Abstract

While TKI are the preferred first-line treatment for chronic phase (CP) CML, alloHCT remains an important consideration. The aim is to estimate residual life expectancy (RLE) for patients initially diagnosed with CP CML based on timing of alloHCT or continuation of TKI in various settings: CP1 CML, CP2+ [after transformation to accelerated phase (AP) or blast phase (BP)], AP, or BP. Non-transplant cohort included single-institution patients initiating TKI and switched TKI due to failure. CIBMTR transplant cohort included CML patients who underwent HLA sibling matched (MRD) or unrelated donor (MUD) alloHCT. AlloHCT appeared to shorten survival in CP1 CML with overall mortality hazard ratio (HR) for alloHCT of 2.4 (95% CI 1.2–4.9; p=0.02). In BP CML, there was a trend towards higher survival with alloHCT; HR=0.7 (0.5–1.1; p=0.099). AlloHCT in CP2+ [HR=2.0 (0.8–4.9), p=0.13] and AP [HR=1.1 (0.6–2.1); p=0.80] is less clear and should be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukemia, allogeneic stem cell transplant, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors

INTRODUCTION:

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have changed the therapeutic landscape of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) since the introduction of imatinib mesylate nearly 20 years ago1. Tolerable side effect profiles and high efficacy of the currently five FDA approved TKIs have improved both quality of life and life expectancy of patients with CML1–4; consequently, TKIs have replaced interferon and allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloHCT) as first line treatment of patients with CML.

Due to efficacy of available TKIs and the ability to sequence them when one is unsuccessful, life expectancy of newly diagnosed chronic phase (CP) CML patients approaches that of the general population5,6. However, a small subset of CP CML patients never achieve optimal response to TKIs, and secondary resistance rates in patients initially responding to TKI therapy occur at a rate of 2–4% per year7. Second-line therapy in imatinib-resistant patients with second generation TKIs dasatinib, nilotinib and bosutinib yield lower complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) rates of approximately 40–50% 8, with even lower rates of major molecular response (MMR). Treatment beyond second TKI failure, although effective with ponatinib, is limited by safety concerns whereas prospective data with other TKI options is limited to bosutinib with major cytogenetic response (MCyR) rates of approximately 40% 9,10. Additionally, majority of patients with CML cannot be considered cured with TKIs as approximately 40–60% patients relapse after elective TKI discontinuation 11–13.

Although use of alloHCT has declined significantly since the introduction of TKI, it remains an effective and curative option, and mortality rates have decreased considerably in the last two decades making it an important consideration for some patients with TKI failure 14. Yet, with increased availability of multiple TKI, timing of alloHCT is undefined. There is decreasing appetite for performing alloHCT before a patient experiences failure of multiple TKI but waiting too long to perform alloHCT may decrease the success rates of transplant as the time from diagnosis to transplant is a recognized adverse prognostic feature. In addition, outcomes in alloHCT are clearly worse in patients with advanced stage CML at the time of transplantation than when performed in CP.15 In this analysis we aimed to explore the timing of alloHCT using two large databases: one based on TKI therapy and one for alloHCT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Data Source

The CIMBTR (Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation Research) includes data from more than 450 international transplant centers. They contribute detailed data on consecutive autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplants. Compliance is monitored by on-site audits and patients are followed longitudinally. Computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. Studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. Protected Health Information used in the performance of such research is collected and maintained in CIBMTR’s capacity as a Public Health Authority under the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

CIBMTR collects data at two levels: Transplant Essential Data (TED) level and Comprehensive Report Form (CRF) level. TED-level data is an internationally accepted standard data set that contains a limited number of key variables for all consecutive transplant recipients. TED and CRF level data are collected pre-transplant, 100 days and six months post-transplant, annually until year 6 post-transplant and biannually thereafter until death.

MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) Leukemia Department database includes all leukemia patients treated at MDACC and includes demographics, disease characteristics, treatment modalities with start and stop dates, response, and dates of evaluation. Longitudinal follow-up is conducted for patients per protocol and institutional guidelines. Data are recorded, submitted and checked by physician. Clinical trials are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. Protected Health Information used in the performance of such research is collected and maintained in MDACC’s capacity under the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Patient population

We compiled data from these two large databases: MDACC for patients treated with TKI and CIBMTR for patients treated with alloHCT. Patients ages 18–65 were included if they had been diagnosed with Philadelphia chromosome or BCR-ABL1-positive CP CML between 1/1/2001 and 12/31/13 and initiated on TKI therapy within 6 months of diagnosis. Patients with prior alloHCT or auto-HCT were excluded. Patients who switched TKIs for any reason other than failure (as defined by European Leukemia Net 2013 criteria) were excluded in order to have a more objectively defined population. Patients who remained on their initial TKI were also excluded from analysis as they were not deemed to have experienced TKI failure; thus alloHCT would not have been a consideration in the treatment of their CML. Dates and reasons of TKI switch were gathered through chart review. Staging of CML into CP, accelerated (AP), or blast phase (BP) CML was based on standard criteria 16,17 (Supplemental Table 1).

The alloHCT cohort was extracted from the CIBMTR. Patients ages 18–65 at the time of transplant were included if they had a diagnosis of Philadelphia chromosome or BCR-ABL1-positive CML and underwent HLA sibling matched (MRD) or matched unrelated donor (MUD) alloHCT (myeloablative or reduced intensity/non-myeloablative) between 1/1/2001 and 12/31/2013. Myeloablative regimens are defined as a regimen that produces pancytopenia within 1–3 weeks from administration that would be expected to be irreversible and fatal without hemopoietic stem cell infusion, as previously defined18. Last follow up date was 12/31/2016. Staging of CP, AP, BP CML was based on WHO Criteria 19 (Supplemental Table 1).

Study Definitions and Statistical analysis

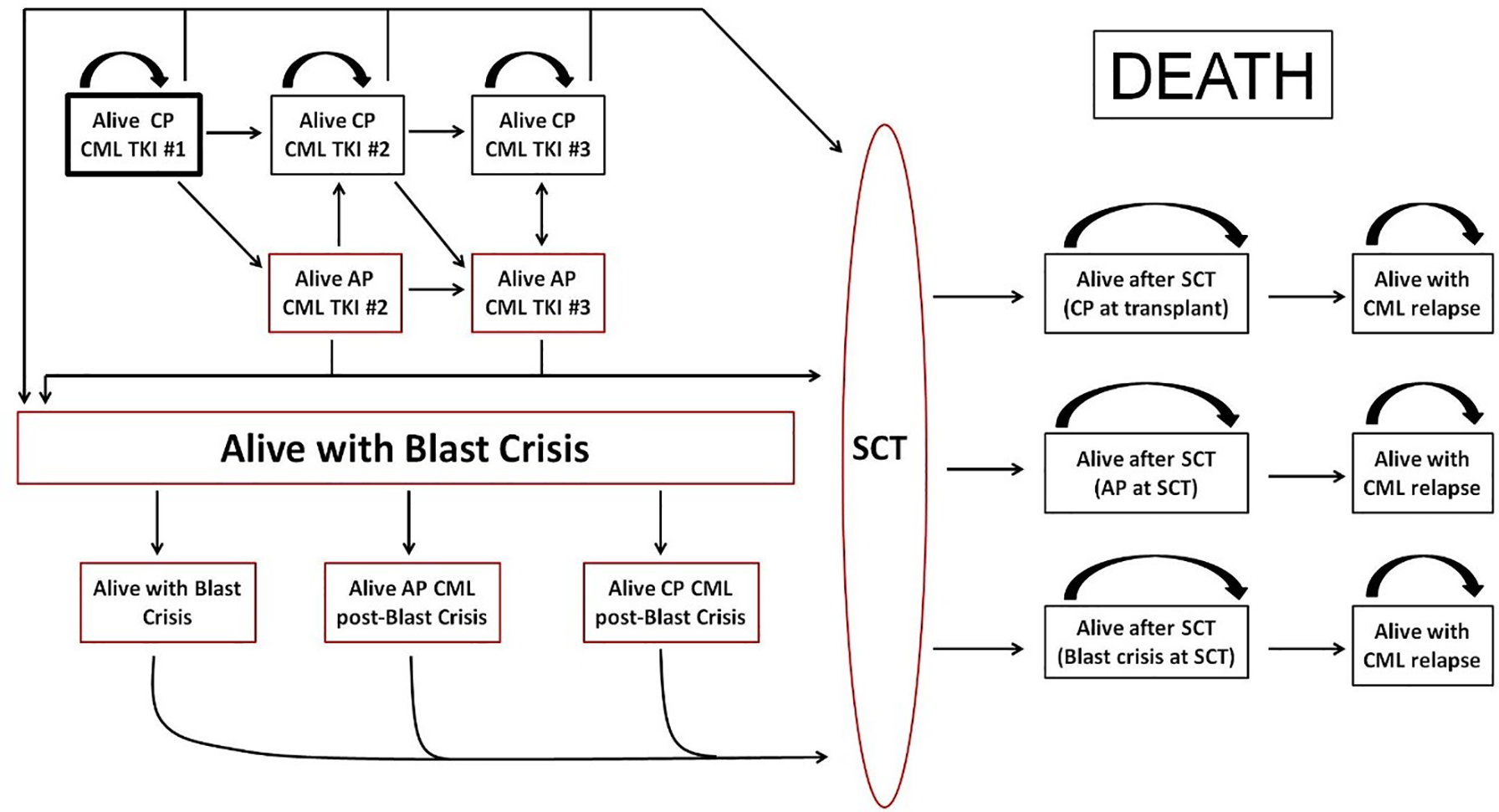

The decision to treat with TKI or HSCT was made by the treating physician according to practice guidelines and/or institutional algorithms. We used Cox proportional hazards model on the data set combining patients who received and did not receive alloHCT, to estimate the hazard ratios. We used Kaplan-Meier estimator to evaluate survival time distributions, and used integration of Kaplan Meier curves to estimate the residual life-expectancy (RLE) of patients with CP CML at initial diagnosis based on timing of alloHCT in various settings: alloHCT at CP1, at CP2+ (after transformation to AP or BP), at AP, or at BP, or continuation of 2nd or 3rd TKI at CP1, CP2+, AP or BP, see Figure 1. That is to say, for a particular group of patients, their RLE (all restricted to 10 years throughout this article) is estimated by the area under their survival curve from 0 to 10. The restriction of 10 years is chosen to be slightly less than the maximum follow-up time. Death from any cause was counted as an event.

Figure 1:

Disease States and Possible Pathways for CML patient

CP=chronic phase

CML=chronic myeloid leukemia

TKI=tyrosine kinase inhibitor

AP=accelerated phase

SCT=stem cell transplant

RESULTS:

A total of 1361 patients were included in the analysis: 138 in the MDACC cohort and 1223 in CIBMTR cohort (Table 1). In the MDACC cohort, 77 (56%) were male and median age was 46 years (range 19–64). In the CIBMTR cohort, 703 (57%) were male and median age was 39 years (range 18–69), P<0.01 for both gender and age. Median follow up time was 96.4 months for the MDACC cohort and 59.6 months for the CIBMTR cohort. Most transplanted patients (n=1029 or 84%) underwent a myeloablative alloHCT.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics of the TKI and SCT cohorts

| MDACC (n=138) | CIBMTR (n=1223) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| Median (range) | 46.0 (19, 64) | 38.8 (18, 65) | <0.01 |

| 18–49 | 88 (64%) | 974 (80%) | |

| 50–65 | 50 (36%) | 249 (20%) | |

| Gender | 0.72 | ||

| Male | 77 (56%) | 703 (57%) | |

| Female | 61 (44%) | 520 (43%) | |

| Year of Transplant | |||

| 2001–2004 | N/A | 534 (44%) | |

| 2005–2008 | 515 (42%) | ||

| 2009–2013 | 174 (14%) | ||

| Type of Transplant | |||

| Matched Related | N/A | 686 (56%) | |

| Matched Unrelated | 537 (44%) | ||

| Nonmyeloablative | N/A | 154 (12%) | |

| Myeloablative | 1029 (84%) | ||

| Missing | 40 | ||

| Number of TKIs used | |||

| Median (range) | 2 (1–4) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Last known stage of | <0.0001 | ||

| CML | |||

| CP1 | 53 (38%) | 738 (60%) | |

| CP2+ | 12 (9%) | 255 (21%) | |

| AP | 20 (14%) | 148 (12%) | |

| BP | 53 (38%) | 82 (7%) | |

| Progressed to AP/BP | 73 (52%) | 230 (19%) | |

Abbreviations: CML (chronic myeloid leukemia), CP1 (first chronic phase), CP2+ (return to chronic phase after progression to accelerated or blast phase CML), AP (accelerated phase), BP (blast phase)

Reasons for transplant in CP1 are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Half of the patients (n=370) underwent alloHCT due to limited access to TKI (mostly patients from outside United States). Only 1% (n=8) underwent alloHCT in CP1 due to failure of 3 or more lines of therapy. Causes of death were mainly from primary disease (42%) followed by GVHD (17%) and infection 14%), Supplemental Table 3.

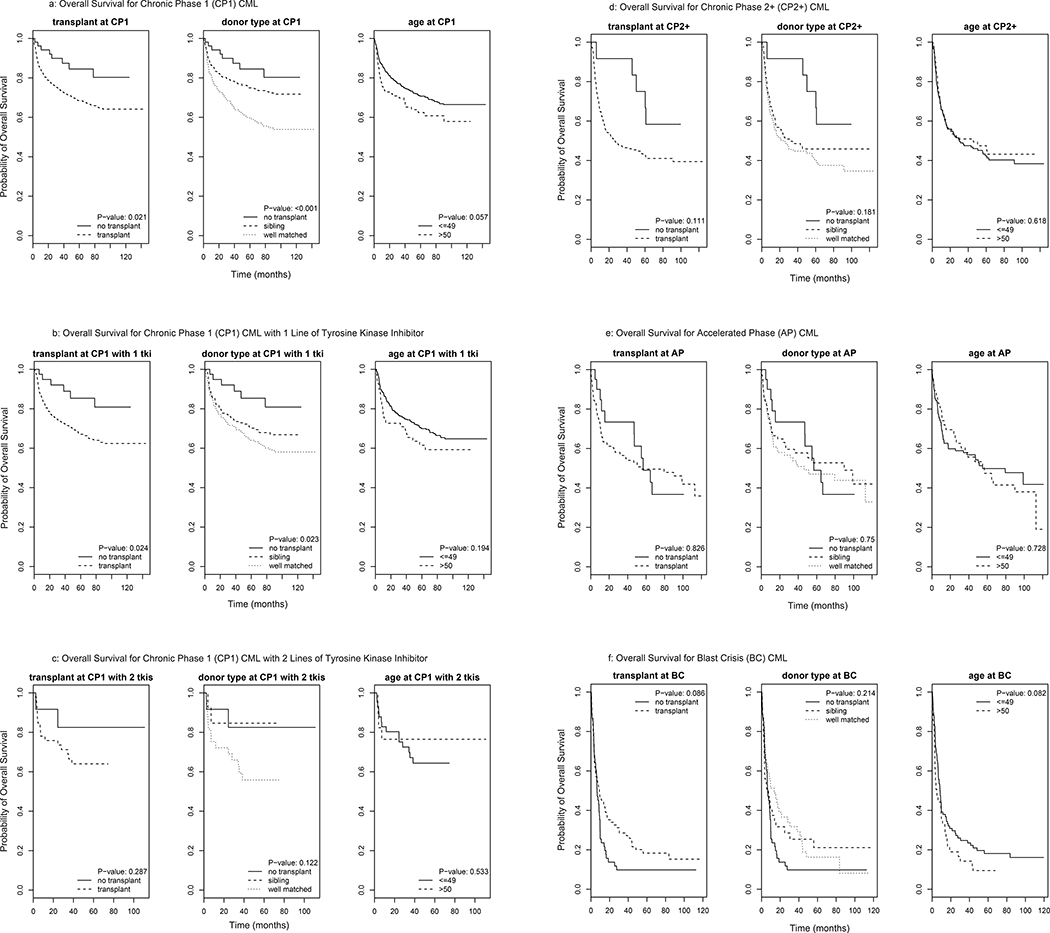

Table 2 depicts the effect of transplant and age on survival by univariate analysis. In CP1 alloHCT was associated with worse overall survival compared to change to a 2nd TKI when there is failure to the first TKI. Multivariate analysis (MVA) confirmed that compared to non-HCT, alloHCT was associated with inferior OS (hazard ratio (HR) of 2.4 (95% CI 1.2–4.9; p=0.02)]). Increased mortality was more pronounced in MUD HCT patients [HR of MUD HCT vs. non-HCT =3.3 (95% CI 1.6–6.7, p=0.001)] than MRD HCT [HR of MRD HCT vs. non-HCT =1.9 (95% CI 0.9–3.8, p=0.1)], Table 3. As compared to non-HCT, alloHCT had a HR of 1.5 (95% CI 1.1–2.1, p=0.02) in the subgroup of patients aged ≥50. Mean RLE was 7.1 years (95% CI 6.8–7.5) if patients underwent alloHCT in CP1 CML vs. 8.5 years (95% CI 7.6–9.5) if they did not (Table 4 and Figure 2a). CP1 CML patients on their 2nd TKI who developed failure also had an improved survival if they switched to a 3rd TKI than if they went on to alloHCT. In this setting the HR for alloHCT compared to non-HCT was 2.1 (95% CI 0.5–9.2; p=0.3; Table 3). The corresponding mean RLE was 6.8 years (5.6–8.3) for CP1 CML patients on 2nd TKI if they underwent alloHCT vs. 8.5 years (6.6–10) continuing on TKI therapy (Table 4).

Table 2:

Univariate Analysis for overall survival

| CP 1 (n=791) | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

| Transplant Status | |||

| No transplant (n=53) | 1.000 | ||

| Transplant (n=738) | 2.247 | 1.109, 4.552 | 0.025 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=459) | 1.730 | 0.841, 3.556 | 0.136 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=279) | 3.052 | 1.489, 6.254 | 0.002 |

| Age≥50 (n=114) | 1.389 | 0.988, 1.950 | 0.058 |

| CP 1 with 1 TKI (n=477) | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

| Transplant Status | |||

| No transplant (n=41) | 1.000 | ||

| Transplant ((N=436) | 2.490 | 1.099, 5.643 | 0.028 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=231) | 2.169 | 0.936, 5.025 | 0.136 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=205) | 2.818 | 1.226, 6.473 | 0.014 |

| Age≥50 (n=69) | 1.330 | 0.863, 2.050 | 0.196 |

| CP 1 with 2 TKI (n=59) | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

| Transplant Status | |||

| No transplant (n=12) | 1.000 | ||

| Transplant (n=47) | 2.180 | 0.501, 9.487 | 0.299 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=12) | 0.859 | 0.120, 6.107 | 0.88 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=14) | 2.792 | 0.634, 12.291 | 0.175 |

| Age≥50 (n=17) | 0.704 | 0.231, 2.138 | 0.536 |

| CP 2+ (n=267) | |||

| Transplant Status | |||

| No transplant (n=12) | 1.000 | ||

| Transplant (n=255) | 2.037 | 0.833, 4.981 | 0.119 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=119) | 1.862 | 0.745, 4.651 | 0.183 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=136) | 2.183 | 0.883, 5.398 | 0.091 |

| Age≥50 (n=89) | 0.915 | 0.644, 1.300 | 0.620 |

| AP (n=168) | |||

| Transplant Status | |||

| No transplant (n-=20) | 1.000 | ||

| Transplant (n=148) | 1.074 | 0.569, 2.028 | 0.825 |

| Matched Related Transplant (67) | 0.977 | 0.491, 1.947 | 0.948 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=81) | 1.159 | 0.596, 2.256 | 0.662 |

| Age≥50 (n=47) | 1.085 | 0.685, 1.715 | 0.729 |

| BP (n=135) | |||

| Transplant Status | |||

| No transplant (n=53) | 1.000 | ||

| Transplant (n=82) | 0.717 | 0.490, 1.050 | 0.087 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=41) | 0.756 | 0.476, 1.199 | 0.235 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=41) | 0.686 | 0.440, 1.070 | 0.096 |

| Age≥50 (n=51) | 1.405 | 0.956, 2.066 | 0.083 |

Table 3:

Multivariate Analysis for overall survival

| CP1 (n=791) | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transplant (n=738) | 2.401 | 1.182, 4.879 | 0.015 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=459) | 1.850 | 0.897, 3.812 | 0.095 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=279) | 3.274 | 1.592,6.730 | 0.001 |

| Age≥50 (n=114) | 1.484 | 1.055, 2.088 | 0.023 |

| CP1 with 1 TKI (n=477) | |||

| Transplant (n=436) | 2.623 | 1.154, 5.963 | 0.021 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=231) | 2.279 | 0.981, 5.291 | 0.055 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=205) | 2.991 | 1.297, 6.897 | 0.010 |

| Age≥50 (n=69) | 1.444 | 0.934, 2.230 | 0.097 |

| CP1 with 2 TKI (n=59) | |||

| Transplant (n=47) | 2.116 | 0.484,9.241 | 0.319 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=14) | 0.862 | 0.120,6.145 | 0.882 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=33) | 2.773 | 0.619, 12.418 | 0.182 |

| Age≥50 (n=17) | 0.966 | 0.306, 3.047 | 0.954 |

| CP2+ (n=267) | |||

| Transplant (n=255) | 2.010 | 0.817, 4.942 | 0.128 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=119) | 1.841 | 0.733, 4.623 | 0.193 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=136) | 2.156 | 0.867, 5.365 | 0.098 |

| Age≥50 (n=89) | 0.959 | 0.674, 1.367 | 0.819 |

| AP (n=168) | |||

| Transplant (n=148) | 1.098 | 0.576, 2.093 | 0.776 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=67) | 0.998 | 0.498, 2.001 | 0.996 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=81) | 1.193 | 0.606, 2.349 | 0.610 |

| Age≥50 (n=47) | 1.111 | 0.697, 1.772 | 0.657 |

| BP (n=135) | |||

| Transplant (n=82) | 0.726 | 0.496, 1.062 | 0.099 |

| Matched Related Transplant (n=41) | 0.793 | 0.498, 1.261 | 0.327 |

| Matched Unrelated Transplant (n=41) | 0.677 | 0.434, 1.056 | 0.085 |

| Age≥50 (n=51) | 1.414 | 0.957, 2.089 | 0.082 |

Table 4:

Mean Residual Life by treatment in the various CML stages

| SCT | TKI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean Residual Life | 95% CI | n | Mean Residual Life | 95% CI | ||

| CP1 | 738 | 7.136 | 6.789, 7.502 | 53 | 8.484 | 7.560, 9.520 | |

| CP1 with 1 TKI | 436 | 7.044 | 6.604, 7.518 | 41 | 8.579 | 7.588, 9.681 | |

| CP1 with 2 TKI | 47 | 6.825 | 5.621, 8.305 | 89 | 8.453 | 6.646, 10 | |

| CP2+ | 255 | 4.668 | 4.084, 5.346 | 12 | 7.382 | 5.557, 9.709 | |

| AP | 148 | 5.313 | 4.501, 6.305 | 20 | 5.608 | 3.956, 8.245 | |

| BC | 82 | 2.571 | 1.807, 3.756 | 53 | 1.536 | 0.914, 2.826 |

Figure 2:

Overall survival for various stages of CML

CML = chronic myeloid leukemia

CP1= chronic phase 1

CP2+ = chronic phase 2+

AP=accelerated phase

BC=blast crisis

For patients with CML in CP2+ there is also an advantage for those receiving TKI. On MVA, The HR was 2.0 (95% CI 0.8–4.9, p=0.13) for alloHCT compared to non-HCT, Table 3 and Figure 2d. HR was 1.8 (95% CI 0.7–4.6, p=0.19) and 2.2 (95% CI 0.9–5.4; p=0.10) for MRD and MUD HCT, respectively as compared to non-HCT. Mean RLE was 4.7 (95% CI 4.1–5.3) years for patients undergoing alloHCT in CP2+ CML compared to 7.4 (95% CI 5.6–9.7) years with TKI continuation, Table 4.

The outcome for patients with AP CML was not significantly different for patients treated with TKI or with alloHCT, Figure 2e. The HR was 1.1 for alloHCT (95% CI 0.6–2.1; p=0.8) compared to non-HCT. The corresponding mean RLE was 5.3 (95% CI 4.5–6.3) years for AP patients undergoing alloHCT and 5.6 years (95% CI 4.0–8.2) for those continuing with TKI, Table 4.

Among patients in BP CML, there was a trend towards improved survival with alloHCT compared to continuation of TKI therapy. By MVA the HR was 0.7 (95% CI 0.5–1.1; p=0.099) for alloHCT compared to non-HCT for the total population. The corresponding HR was 0.8 (95% CI 0.5–1.3; p=0.33) for MRD HCT and 0.7 (95% CI 0.4–1.0; p=0.08) for MUD HCT compared to non-HCT. The mean RLE for patients with BP CML was 2.6 (95% CI 1.8–3.8) years for the patients who underwent alloHCT in BP compared to 1.5 (95% CI 0.9–2.8) years for those who continued their TKI. There seems to be more long term survivors with transplant as the tail end of the survival curve is higher for the alloHCT arm compared with TKI continuation (Figure 2f).

DISCUSSION:

While alloHCT offers a curative option for a significant percentage of patients with CML, risks of early treatment related morbidity and long-term complications such as graft-versus-host disease have tampered its use in recent years, considering the excellent results achieved with TKI as initial therapy and the availability of several inhibitors that may still offer clinical benefit after failure of an initial TKI attempt. The ELN recommendations offer suggestions of the recommended timings for searching for a donor and performing HCT. However, these recommendations are based on personal experience and small series. To date, there have been no studies to evaluate the optimal timing of performing alloHCT in patients with CML who fail one or more TKIs.

Our analysis suggests that in early stages of the disease TKI therapy offers a survival benefit compared to alloHCT. This benefit remains nearly constant even after failure of a second TKI as long as the patient remains in CP. The survival curves in Figure 2 seem to favor TKI continuation over both MRD and MUD transplant for patients in CP1 and there is a trend of favoring TKI continuation in CP2+ CML. This survival advantage observed with non-HCT therapies appears to diminish as the disease progresses to AP (Figure 2), suggesting that a multitude of factors including sensitivity to remaining TKIs, affordability and availability of TKIs (significantly influenced by country of residence), comorbidities, toxicity of transplant regimens and subsequent complications from transplant influence the outcomes and survival. There seems to a survival advantage with HCT for those who progressed to BP CML as evidenced by higher proportion of survivors who underwent alloHCT at the tail end of the survival curve (Figure 2f), but perhaps given the small sample size this finding was not statistically significant. Both MRD and MUD alloHCT seem to benefit survival for those with BP CML over TKI continuation.

Since benefit for patients with AP is less clear, the choice of HCT versus TKI continuation should be determined on a case-by-case basis, dependent on mutation status, age and comorbidities of the patient, type and availability of donor used, and remaining TKI options available. Interestingly, the survival curves for alloHCT and TKI continuation (Figure 2e) in AP cross. Initially, survival is lower for the alloHCT cohort, likely due to transplant-related mortality. However, there is a subset who achieve long term survival likely due to disease control with alloHCT, as evidenced by the tail end of the curve. These results are similar to those reported in a series by Nicolini et al specifically for patients with T315I treated with ponatinib 20. Patients with CP treated with ponatinib had a superior overall survival compared to those who received HCT. For patients in AP there was no difference between the two cohorts, whereas for the BP patients receiving HCT, while still doing very poorly, had a better overall survival compared to patients treated with ponatinib.

Our analysis suffers from limitations that should be taken into account when considering the results. First, this was a retrospective study and there may have been inherent biases between the non-transplant and transplant group that we are unable to determine. The patients referred to alloHCT may have had more aggressive disease by variables that are difficult to account for in a registry series. Additionally, availability and affordability of TKIs may not be equal in all countries and account for differences in transplant referrals in CP1. Prioritization therefore should be adapted to available options and financial considerations that may affect desirability of TKI and/or SCT in specific circumstances. In addition, patients in both cohorts may be inherently different than the patients treated in the community, who may have more comorbidities or a less favorable disease biology (e.g., Sokal risk score)21.

Furthermore, the number of patients in the non-transplant cohort were small and thus comparisons between TKI continuation vs. alloHCT for the CP2+, AP and BP groups were not statistically significant and the comparison may have been underpowered to detect a noticeable difference in overall survival. This cohort is also derived from a single institution with a dedicated CML clinic and considerable expertise where the results may not be representative of what can be expected in other settings. The reported median survival for CML patients in the SEER database for example is considerably shorter than what is achieved at MDACC 6,22. Although some of this may be related to access to TKI, factors such as patient characteristics and the local expertise may also contribute.

It is notable that transplant results were quite good for match related donors and inferior survival for transplant may be the result of decreased survival in matched unrelated donor transplants. Moreover, 84% of patients in the alloHCT cohort underwent a myeloablative regimen. More recent retrospective studies have demonstrated that nonmyeloablative regimens for CML are well tolerated with less transplant related mortality and non-inferior for disease related mortality, particularly in CP23,24. The survival outcomes for AP and BP CML with a nonmyeloablative regimen compared with TKI continuation will need to be studied in the future.

Additionally, the staging in the non-transplant and transplant cohort were different. Stage of CML in non-transplant cohort was determined using the standard criteria used in all of the pivotal TKI studies, while the stage of CML in the transplant cohort more closely aligned with the WHO criteria. We did not change the staging of the nontransplant cohort based on WHO criteria as treatment decisions were made based on standard rather than WHO criteria. In addition, the subjectivity of some of the WHO criteria (e.g., increasing spleen size and increasing WBC unresponsive to therapy) make it difficult to apply retrospectively. This introduces an uneven variable that cannot be resolved in an analysis such as ours. This “stage migration” phenomenon has been described in the literature whereby classifying patients based on WHO criteria improves their outcomes without any therapeutic intervention due to differences in definition of stage of CML25–27. However, when we reclassified the CIBMTR cohort based on the percentage of bone marrow blasts to better align with the standard criteria, only 6 of 137 patients were reclassified from BP to AP and only 10 of 279 patients were reclassified from AP to CP, representing less than 5% of the entire cohort.

Of note, we first aimed to use Markov Decision Analysis model using the TreeAge decision modeling software program. However, the Markov model is inadequate for this analysis due to the fundamental assumption in Markov decision analyses that any outcome of a particular disease state in any cycle is only dependent on the properties of the current cycle and has no “memory” of prior cycles28. Hence, the Markov model underestimated life expectancy in the alloHCT patient as the transition probabilities calculated for each cycle length (e.g. 3-, 6-, 12- month cycles) were based on survival data in the first year following alloHCT. Because transplant-related mortality is greater during the first year (10–20% chance of death), and chance of death decreased significantly after the first year with at least 50% of patients cured of CML, the probability of death of alloHCT patients was overestimated as the Markov Decision Analysis does not account for the decreasing probability of death overtime after alloHCT. We thus used the integration of Kaplan Meier curves to calculate life expectancy, which may provide a more realistic representation of expected outcomes in this setting.

In conclusion, our analysis may help guide treatment decisions in the earlier and late stages of CML. TKI may result in better outcome in CP1 and HCT in BP. Decisions for intermediate stages (CP2+ and AP) are less clearly guided. Despite a trend for CP2+ in favor of TKI and null effect in AP, the caveats mentioned earlier suggest that decisions should be made considering in addition factors such as mutation status, availability of TKI and donor, comorbidities, patient characteristics, conditioning regimen and cost. Although prospective randomized trials would ideally help resolve these questions, such studies are unfortunately unlikely to be conducted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We appreciate the suggestions and comments by the CIBMTR committee in the writing of the protocol and the manuscript.

FUNDING: The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 4U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-17-1-2388 and N0014-17-1-2850 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from *Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; *Amgen, Inc.; *Amneal Biosciences; *Angiocrine Bioscience, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Astellas Pharma US; Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc.; Be the Match Foundation; *bluebird bio, Inc.; *Bristol Myers Squibb Oncology; *Celgene Corporation; Cerus Corporation; *Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Gamida Cell Ltd.; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Immucor; *Incyte Corporation; Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; *Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Juno Therapeutics; Karyopharm Therapeutics, Inc.; Kite Pharma, Inc.; Medac, GmbH; MedImmune; The Medical College of Wisconsin; *Mediware; *Merck & Co, Inc.; *Mesoblast; MesoScale Diagnostics, Inc.; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; *Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; *Neovii Biotech NA, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. – Japan; PCORI; *Pfizer, Inc; *Pharmacyclics, LLC; PIRCHE AG; *Sanofi Genzyme; *Seattle Genetics; Shire; Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; *Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; Telomere Diagnostics, Inc.; and University of Minnesota. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

DISCLOSURE/DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST:

B.H., X.L., X.H. R.S.T., Z.H., K.W.A., Y.L., U.P., W.S. have no relevant conflicts of interest to report.

H.C.L. has received consulting fees and research funding from Takeda pharmaceuticals. Dr. Ayman Saad’s institution receives research funding from Amgen, Kadmon, OrcaBio. Jan Cerny has received research funds from Pfizer pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Aaron Gers has received research funding from Celgene, Pfizer, CTI biopharma, Dr. Michael Grunwald’s institution has received research funding from Forma Therapeautics, Amgen, Genentech, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, and has stock ownership in Medtronic, and has provided consulting for Agios, Abbvie, Amgen, Cardinal Health, Celgene, Incyte, Merck, Pfizer, Trovagene, Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Richard Olsson has received research funding from AstraZeneca. Dr. Farhad Ravandi has received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer. Dr. Jorge Cortes has received research funding to his institution from Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, Sun Pharma and has acted as a consultant for Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, and Takeda.

* Corporate Members

REFERENCES

- 1.Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(14):1031–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn EA, Glendenning GA, Sorensen MV, et al. Quality of life in patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia on imatinib versus interferon alfa plus low-dose cytarabine: results from the IRIS Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(11):2138–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, Kantarjian H, et al. Activity of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(14):1038–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):994–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower H, Bjorkholm M, Dickman PW, Hoglund M, Lambert PC, Andersson TM. Life Expectancy of Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Approaches the Life Expectancy of the General Population. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2851–2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki K, Strom SS, O’Brien S, et al. Relative survival in patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia in the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor era: analysis of patient data from six prospective clinical trials. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2(5):e186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O’Brien SG, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2408–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantarjian HM, Giles FJ, Bhalla KN, et al. Nilotinib is effective in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase after imatinib resistance or intolerance: 24-month follow-up results. Blood;117(4):1141–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg RJ, Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, et al. The use of nilotinib or dasatinib after failure to 2 prior tyrosine kinase inhibitors: long-term follow-up. Blood. 2009;114(20):4361–4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim AR, Paliompeis C, Bua M, et al. Efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as third-line therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase who have failed 2 prior lines of TKI therapy. Blood. 2010;116(25):5497–5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rea D, Nicolini FE, Tulliez M, et al. Discontinuation of dasatinib or nilotinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: interim analysis of the STOP 2G-TKI study. Blood. 2017;129(7):846–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norimitsu Kadowaki TK, Kuroda Junya, Nakamae Hirohisa, Matsumura Itaru, Miyamoto Toshihiro, Ishikawa Jun, Nagafuji Koji, Imamura Yutaka, Yamazaki Hirohito, Shimokawa Mototsugu, Akashi Koichi and Kanakura Yuzuru. Discontinuation of Nilotinib in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Who Have Maintained Deep Molecular Responses for at Least 2 Years: A Multicenter Phase 2 Stop Nilotinib (Nilst) Trial. Blood. 2016;128:790. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahon FX, Rea D, Guilhot J, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre Stop Imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(11):1029–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Speck B, Bortin MM, Champlin R, et al. Allogeneic bone-marrow transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Lancet. 1984;1(8378):665–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visani G, Rosti G, Bandini G, et al. Second chronic phase before transplantation is crucial for improving survival of blastic phase chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2000;109(4):722–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarjian HM, Deisseroth A, Kurzrock R, Estrov Z, Talpaz M. Chronic myelogenous leukemia: a concise update. Blood. 1993;82(3):691–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talpaz M, Silver RT, Druker BJ, et al. Imatinib induces durable hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with accelerated phase chronic myeloid leukemia: results of a phase 2 study. Blood. 2002;99(6):1928–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(12):1628–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100(7):2292–2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolini FE, Basak GW, Kim DW, et al. Overall survival with ponatinib versus allogeneic stem cell transplantation in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias with the T315I mutation. Cancer. 2017;123(15):2875–2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballard DJ, Bryant SC, O’Brien PC, Smith DW, Pine MB, Cortese DA. Referral selection bias in the Medicare hospital mortality prediction model: are centers of referral for Medicare beneficiaries necessarily centers of excellence? Health Serv Res. 1994;28(6):771–784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cmyl.html. Cancer Stat Facts: Leukemia - Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML). SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program)2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen MH, Chiou TJ, Lin PC, et al. Comparison of myeloablative and nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2007;86(3):275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Or R, Shapira MY, Resnick I, et al. Nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia in first chronic phase. Blood. 2003;101(2):441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortes JE, Talpaz M, O’Brien S, et al. Staging of chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era: an evaluation of the World Health Organization proposal. Cancer. 2006;106(6):1306–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortes J, Kantarjian H. Advanced-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2003;40(1):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cortes JE, Talpaz M, Giles F, et al. Prognostic significance of cytogenetic clonal evolution in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia on imatinib mesylate therapy. Blood. 2003;101(10):3794–3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sonnenberg FA, Beck JR. Markov models in medical decision making: a practical guide. Med Decis Making. 1993;13(4):322–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.