Abstract

Although past research has noted longitudinal, and sometimes bi-directional, associations between marital interactions, loneliness, and physical health, previous work has not identified long-term associations and differential associations over life-course stages (i.e., mid-life and later adulthood). Utilizing a life-course stress process perspective and a sample of 250 couples in enduring marriages over 17 years (2001–2017), a structural equation model within a dyadic framework assessed the unique influences of stressful marital interactions on loneliness and physical health and the variation in bi-directional influences of loneliness and physical health over time. Marital interactions were relatively stable across life stages, yet marital interactions appear to influence loneliness and physical health. Notable distinctions were evident across life stages (from mid-life to later adulthood and then within later adulthood). Findings are discussed with an emphasis on the implications for health promotion and prevention programs targeting couples’ quality of life in later years.

Keywords: physical health, marriage, loneliness, later life, marital conflict

Marriage has been shown to protect against loneliness (defined as subjective feelings of social isolation) in later life, but this protective factor hinges on the context within the marital relationship. For instance, in a marital relationship with frequent negative or stressful interactions between spouses, marriage can actually foster feelings of isolation rather than minimize them (Ayalon et al., 2013). Thus, it is the quality of marital interaction that determines whether marriage is positively or negatively related to the loneliness reported by both spouses (Olson & Wong, 2001). Furthermore, research suggests that stressful marital interactions and loneliness have detrimental physical health impacts (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1996; Luaneigh & Lawlor, 2008), and physical health is increasingly important in later life due to the prevalence of health declines in later life.

Matters are further complicated by the likely bi-directional association between loneliness and physical health (Cacioppo et al., 2010) as physical health limitations also play a role in enhanced loneliness and social isolation (e.g., Cacioppo et al., 2002). The comorbidity and mutual influences between loneliness and physical health have not been fully considered or appropriately modeled in longitudinal marital research, thereby limiting knowledge of how stressful marital interactions result in both loneliness and poor physical health. This is an important direction for research on marriage in later adulthood (defined here as ages 65+ years), given that two defining characteristics of later adulthood is the salience of marital quality and the relatively high risk for disabling health conditions (Carr et al., 2014; Korporaal et al., 2008).

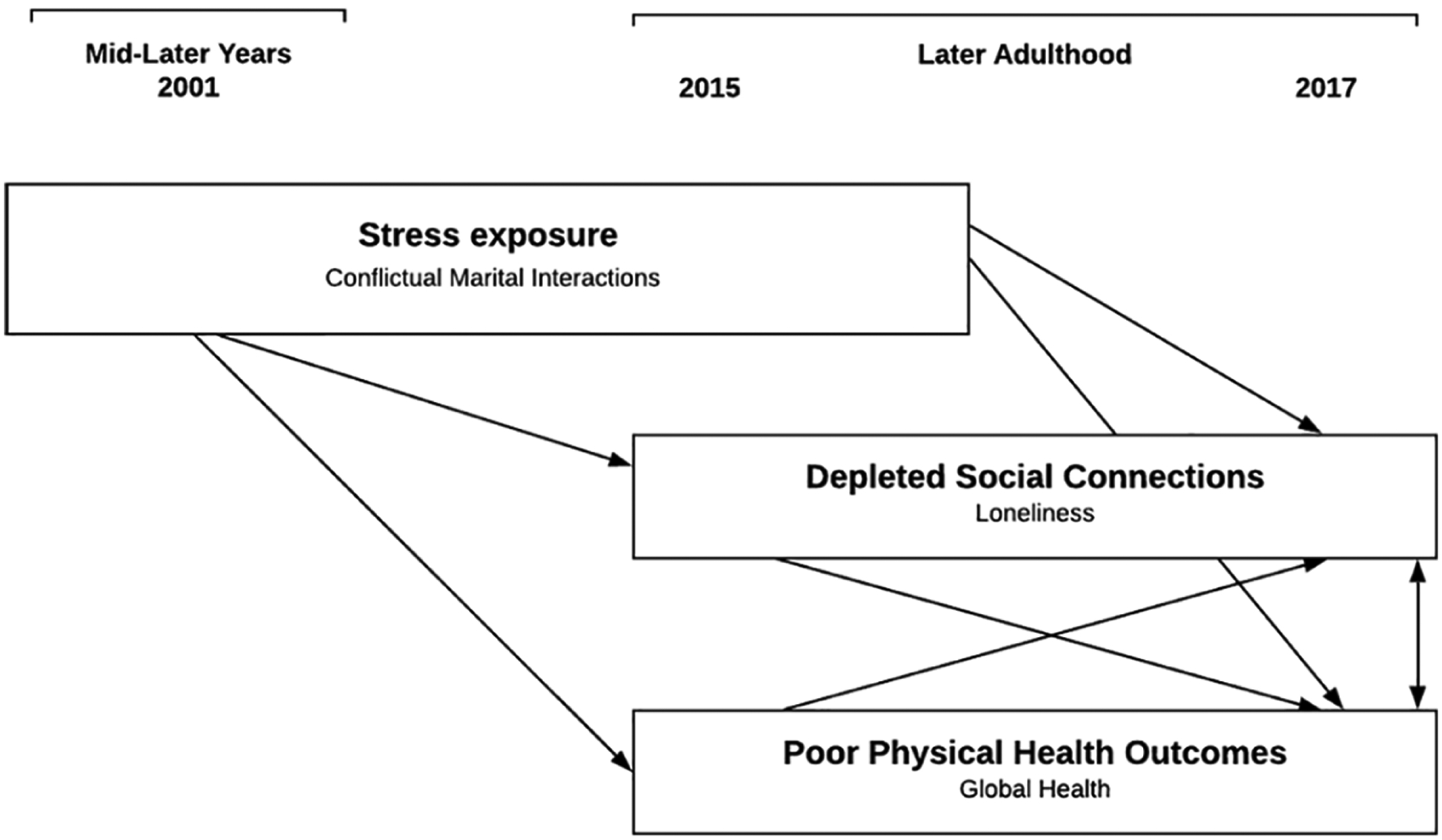

This research, noting associations between stressful marital interactions, loneliness, and physical health over the life course, is consistent with the stress process perspective (Pearlin et al., 2005), which posits that an initial or primary stressor can result in additional, or secondary, stressors in the same stress domain or in additional domains (Pearlin et al., 2005). Also, the stress process perspective acknowledges that stress may proliferate over long periods of time across the life course (Thoits, 2010). Moreover, these primary and secondary stressors can have direct and indirect health consequences that may vary depending on the life stage. As shown in the conceptual model (see Figure 1), we hypothesize that conflictual marital interactions in mid-life operate as a primary stressor that may continue into later years (as a secondary stressor within the same domain) and exert physical health consequences. Moreover, conflictual marital interactions may reduce social resources, particularly connections to others including the spouse, resulting in feelings of loneliness as a secondary stressor, with additional health consequences. Extending the stress process perspective, we also propose reciprocal influences between health outcomes and loneliness over time.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model detailing linkages between conflictual marital interactions, loneliness, and physical health from the mid-later years through later adulthood.

With advancing age, loneliness typically increases as older adults lose connections with loved ones and close friends and their physical health generally declines (Dysktra et al., 2005; Martin & Schoeni, 2014; Perissinotto et al., 2012). Thus, the association between loneliness and physical health may vary depending on the life stage with stronger associations in later life stages (65+ years). Panel studies of married couples with extensive follow-up periods are needed to uncover (a) the unique influences of stressful marital interactions on loneliness and physical health and (b) the variation in bi-directional influences of loneliness and physical health over time between husbands and wives from midlife to later life. The current study seeks to disentangle these potential influences for husbands and wives in enduring marriages over midlife and later life. In order to account for the dependencies between husbands and wives, the analysis is performed within a dyadic framework (see the conceptual model in Figure 1).

The life-course stress process perspective (Pearlin et al., 2005) recognizes that individuals are embedded within numerous social settings, and the family setting is one of the most salient settings (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). A conflictual marital relationship, in particular, represents a major stressor with consequences for individuals’ loneliness and physical health. The stress process framework articulates how stressful contexts, such as marital conflict, activate adverse emotional and physiological processes (Turner, 2010) resulting in both poor physical health and negative emotions, including loneliness. Moreover, previous research has documented that poor physical health and feelings of loneliness mutually influence each other over time (Dysktra et al., 2005; Martin & Schoeni, 2014).

The current study addresses the accumulation of marital experiences for couples in enduring marriages (most of the couples have been married for over 40 years by the final data collection) using prospective data collected from husbands and wives over 17 years (2001–2017). This study examines conflictual marital interactions, particularly destructive problem solving, as one form of stressful interaction between marriage partners at two time points: in their mid-later years (2001; average ages of 50 years and 52 years for husbands and wives, respectively) and again in later adulthood (2015; average ages 64 years and 66 years). Moreover, loneliness and physical health outcomes are assessed at two time points in later adulthood (2015 and 2017). The examination sheds light on how conflictual marital interactions are related to loneliness and physical health both from the mid-later years to later adulthood (2001–2015) and then across later adulthood (2015–2017) while simultaneously examining the stability in loneliness and physical health within later adulthood (2015–2017). The findings of the current study have implications for health promotion and prevention programs targeting couples’ quality of life in later years.

Stressful Marital Interactions and Loneliness

We draw from the cognitive theory of loneliness to contextualize loneliness within the marriage. Loneliness is defined as subjective feelings of social isolation (Ayalon et al., 2013; Dysktra et al., 2005; Victor et al., 2000). According to the cognitive theory of loneliness, it is the subjective perception of unmet desires for social connections (rather than objective number of social connections) that influences individuals’ health and well-being. Furthermore, when identifying the most salient social connections, the marital relationship often rises to the top. For many, their spouse serves as the most intimate psychological, emotional, and physical source of support available to them (Bowlby, 1982; Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Wickrama O’Neal, & Neppl, 2018). This may be particularly true with advancing age, as older adults often invest fewer resources in broader social networks, and, instead, choose to invest their time and energy in nurturing a small number of close personal relationships, such as with their spouse (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). Thus, marital interactions and, relatedly, unmet social desires within the marital relationship may largely drive spouses’ more global evaluations of their intimate social connections and feelings of loneliness.

This link between marriage and subjective feelings of loneliness is supported by existing cross-sectional and longitudinal research indicating that strain in enduring marriages can exert a relatively strong effect on experiences of loneliness (Sabey et al., 2014). A cross-sectional study utilizing data from the Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) found an association between stressful marital interactions and loneliness for husbands and wives over the age of 50 years, leading to the determination that “subjective appraisals of the marital relationship play a major role in one’s sense of loneliness” (Ayalon et al., 2013). A longitudinal study with a two-year follow-up noted that negative marital quality, including interaction behaviors such as making demands, was related to later loneliness for both husbands and wives (Stokes, 2017). Panel studies, however, of couples with longer follow-up periods are necessary to more fully investigate this life-course process with a “long view” (Elder & Giele, 2009) considering the consequences of stressful marital interactions over extended periods of time. Enacting a long view, research with the current study sample has previously identified long-term associations between trajectories of marital strain (growth curves capturing initial levels of strain and rates of change over time) and spouses’ subsequent loneliness in later adulthood (Wickrama, O’Neal, Klopack, et al., 2018). However, these analyses did not consider the simultaneous role of physical health nor did they address the possible variability in associations across life stages.

Stressful Marital Interactions and Physical Health

Numerous reviews have articulated how marriage impacts physical health outcomes (e.g., Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017; Robles et al., 2014). The mechanisms responsible for this marriage–health association are not examined in the current study, but they warrant acknowledgement. These mechanisms can be broadly grouped into psychological, behavioral, and physiological pathways (Berkman & Krishna, 2014), and they are often inter-related. For instance, as a psychological pathway, depressive symptoms are linked to marital stress and often result in poor physical health (Bookwala, 2005), yet depression is also implicated in risky health behaviors, such as poor diet, sedentary behavior, and substance use, that uniquely impact health outcomes (e.g., Swendsen & Merikangas, 2000; O’Neal et al., 2016). At the same time, depressive symptoms result in physiological symptoms, including increased inflammation, which contribute to further physical health declines, particularly the onset of chronic illness (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2009).

Beyond the physiological and behavioral symptoms resulting from psychological mechanisms, stressful marital interactions may act as a chronic stressor exerting a direct physiological toll on biological systems, including cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune systems (McEwen, 1998). As an example, marital disagreements are related to increased blood pressure and elevated stress hormone levels for couples at various life stages, including older couples in enduring marriages (Ewart et al., 1991; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1996; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1997). Meta-analytic findings drawing from previous studies link marital stress to cardiovascular diseases and early mortality (Robles et al., 2014).

Loneliness and Physical Health

In addition to the physical health consequences of marital stress, longitudinal research has shown that loneliness also contributes to physical health declines (e.g., Penninx et al., 1997). Using HRS data, Luo et al. (2012) demonstrated that loneliness was associated with increased mortality risk six years later. Furthermore, there were two-year cross-lagged effects of loneliness on multiple physical health outcomes, including self-rated health and physical limitations. While depressive symptoms, health service utilization, and even physical stress responses (Gerst-Emerson & Jayawardhana, 2015; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1984) may partially explain this association, there is reason to believe that loneliness generally increases physical health risk over and above these related processes (Thurston & Kubzansky, 2009).

Moreover, this effect between loneliness and physical health is bi-directional, with poor health contributing to loneliness in various ways (de Jong Gierveld et al., 2006; Dykstra et al., 2005). For instance, poor health can limit individuals’ autonomy and mobility, thereby restricting their functional status (e.g., their ability to visit places and people) and increasing their time alone, which often results in feelings of loneliness (Dykstra et al., 2005; Victor et al., 2005). Furthermore, health difficulties are also related to declines in socioemotional well-being and mental health (Luo et al., 2012), and loneliness often commences with these declines (Theeke et al., 2012). Compared to healthy individuals, those in poor health also likely spend a larger proportion of their time, energy, and financial resources on health-related matters, which can result in less time to foster the social connections necessary to ward off loneliness.

The Current Study

This study utilizes a life-course stress-process perspective (Pearlin et al., 2005) to examine stressful marital interactions as a risk factor for both spouses’ loneliness and poor physical health. Whereas previous longitudinal research has primarily used relatively short follow-up periods, the extensive follow-up period of the current study allows for an exploration of these associations spanning from mid-later years (2001) to later adulthood (2015 and 2017), which sheds light on the long-term processes involved. Specific research questions include:

Do couples’ stressful marital interactions during their mid-later years (2001) influence husbands’ and wives’ subsequent loneliness and physical health status in later adulthood (2015)?

How do couples’ stressful marital interactions in later adulthood (2015) contribute to change in husbands’ and wives’ loneliness and physical health two years later in 2017?

What is the continuity in husbands’ and wives’ loneliness and physical health over later adulthood (2015–2017) (later life rank order stabilities)?

Do husbands’ and wives’ loneliness and physical health mutually influence each other in their later adulthood (2015–2017)?

Method

Participants and Procedures

The data used to evaluate these hypotheses are from the Midlife Transitions Project (MTP, 2001) and the Later Adulthood Study (LAS, 2015 and 2017). Together, these studies include data over 17 years from rural couples who initially participated in the Iowa Youth and Family Project (IYFP, 1989–1994). The IYFP sample was comprised of rural couples with children, at least one of whom was a seventh grader in 1989 (Conger & Elder, 1994), residing in a cluster of eight counties in north-central Iowa and intended to mirror the economic diversity in the rural Midwest. The MTP and LAS studied the IYFP couple members as they aged through their mid-later years and into later adulthood. While other longitudinal studies have addressed changes in health status in this life stage, the MTP and LAS are unique in their emphasis on relational processes over the life course, primarily understanding nuanced couple processes over time. Consistent with this aim and the study hypotheses, the 250 couples in the current study are those who participated in 2001, 2015, and 2017 data collections and who were consistently married throughout the study period. The majority of couples not included in this analyses were divorced or separated by 2015.

The median yearly family income of the sample in 1989 was $33,240 (ranged from $0 to $259,000). Previous studies with attrition analyses using this sample suggest that consistently married couples in the sample are generally similar to the larger initial sample in most respects. However, as expected, those in enduring marriages reported significantly less marital instability in 1989 (Lee, Wickrama, & O’Neal, 2019).

In 2001, spouses were in their mid-late years; the average ages of husbands and wives were 52 years and 50 years, respectively, and their ages ranged from 44 years to 69 years for husbands and from 42 years to 66 years for wives. On average, the couples had been married for 30 years and had three children. The median age of the youngest child was 22 years. The average number of years of education for husbands and wives was 13.82 years and 13.80 years, respectively. Because there are very few minorities in the rural area studied, all participating families were White.

Measures

Conflictual marital interactions.

Eight items assessed participants’ reports of their spouse’s destructive conflict resolution behaviors in 2001 and 2015 as an indicator of conflictual marital interactions (e.g., “criticizes you or your ideas for solving the problem,” “ignores the problem,” and “seems uninterested in solving the problem”). All items were scored on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = always to 7 = never with higher scores indicating more destructive conflict resolution behaviors. Mean scores were computed separately for husbands and wives in 2001 and 2015 (Husbands: M = 2.21, SD = .80, and M = 2.11, SD = .76 in 2001 and 2015, respectively; Wives: M = 2.38, SD = .92, and M = 2.19, SD = .89 in 2001 and 2015, respectively). The internal consistencies were .91 and .93 in 2001 and .93 and .92 in 2015 for husbands and wives, respectively. Husbands’ and wives’ reports were modeled as observed variables loading onto latent factor of marital conflict in 2001 and 2015 (r for husbands’ and wives’ reports in 2001 and 2015 was .32 and .48, respectively, p<.001).

Loneliness.

Husbands and wives completed the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, Peplau, & Ferguson, 1978) in 2015 and 2017. The 20-item scale was designed to measure one’s subjective feelings of loneliness as well as feelings of social isolation. Participants rated each item on a four-point scale (1 = never; 4 = often), and items were averaged (Husbands: M = 1.66, SD = .45, and M = 1.69, SD = .47 in 2015 and 2017, respectively; Wives: M = 1.64, SD = .50, and M = 1.64, SD = .49 in 2015 and 2017, respectively). The internal consistencies for husbands and wives, respectively, were .91 and .93 in 2015 and .91 and .93 in 2017.

Poor global health.

Self-assessment of poor global health was obtained from husbands and wives in 2001, 2015, and 2017 using three items from the Rand Health Science (1986) overall physical health scale. The first item asked participants to rate their “overall physical health” on a scale from 1 = excellent to 5 = poor. The second and third items asked participants to rate on a scale from 1 = much better to 5 = much worse their physical health in general “compared to one year ago” and compared to “other people your age.” A mean was computed with higher scores representing better physical health (Husbands: M = 3.24, SD = .60, M = 3.23, SD = .74, and M = 3.19, SD = .77 in 2001, 2015, and 2017, respectively; Wives: M = 3.26, SD = .63, M = 3.31, SD = .71, and M = 3.27, SD = .73 in 2001, 2015, and 2017, respectively). The internal consistencies for 2001, 2015, and 2017 were .64, .76, and .79 for husbands and .69, 70, and .75 for wives.

Analysis

Analyses were performed using structural equation modeling (SEM) and Amos software (version 25). We examined couples’ stressful marital interactions during their mid-later years (2001) as a latent construct comprised of husbands’ and wives’ reports of their conflictual marital interactions, and we assessed the influence of stressful marital interactions on their subsequent loneliness and physical health status in later adulthood (2015) after accounting for health status in 2001, allowing for an estimation of how conflictual marital interactions are related to loneliness and to change in physical health status. (A measure of loneliness was not available in 2001.) We also considered how couples’ conflictual marital interactions in later adulthood (2015) contributed to change in their loneliness and physical health two years later in 2017. This model allowed for an assessment of variations in the links between conflictual marital interactions, loneliness, and physical health across (a) distinct life stages (mid-late years and two time points during later adulthood) and (b) varying measurement intervals (2001 to 2015 and 2015 to 2017). Lastly, by incorporating measurements of the same construct at multiple time points (i.e., conflictual marital interactions in 2001 and 2015; physical health in 2001, 2015, and 2017; and loneliness in 2015 and 2017), insight is gained on construct stability over time.

We relied on a range of indices to evaluate the fit of our models, including the chi-square statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Bentler (1990) states that a CFI of more than .95 indicates a respectable model fit, and MacCallum et al. (1996) report that a RMSEA of .08 or less indicates reasonably good model fit as well.

Results

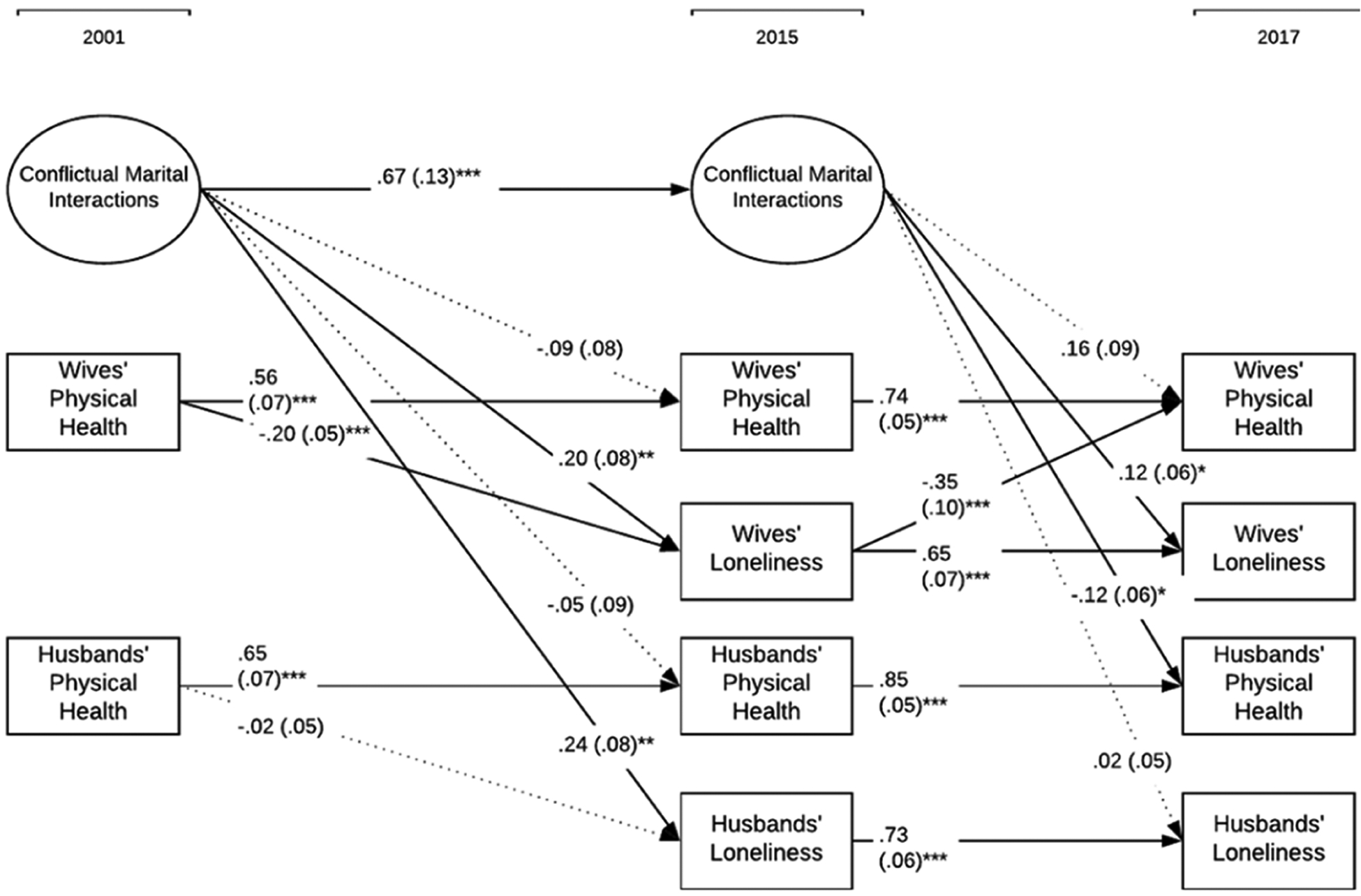

Results from the SEM are presented in Figure 2. Overall, this model fit the data well (χ2/df=1.90, CFI=.96, RMSEA=.06). A latent construct captured couples’ conflictual marital interactions, drawing from husbands’ and wives’ reports of their spouses’ destructive problem-solving behavior in their mid-later years (2001) and later adulthood (2015) (factor loadings of .45 and .71 for husbands’ and wives’ reports in 2001 and .53 and .76 in 2015, respectively). Conflictual marital interactions in their mid-later years (2001) influenced both spouses’ reports of loneliness during later adulthood (2015) (Husbands: b = .240, p<.01; Wives: b =.20, p<.01) after controlling for the influence of previous physical health status (2001), which was related to wives’ loneliness (b = −.20, p<.001) but not husbands (b = −.02, p=.62). After accounting for the relatively high rank-order stability in husbands’ and wives’ physical health from their mid-later years (2001) to later adulthood (2015) (b = .65 and .56, respectively, p<.001), couples’ conflictual marital interactions in their mid-later years were not related to their physical health in later adulthood (Husbands: b = −.05, p = .55; Wives: b = −.09, p = .26).

Figure 2.

A structural equation model assessing stressful marital interactions, physical health, and loneliness in enduring marriages over mid-later years and later adulthood. Unstandardized coefficients are shown with standard errors in parentheses. Broken lines indicate non-significant paths. Constructs at each time period were allowed to correlate. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Like physical health, there was also relatively high stability in couples’ conflictual interactions from 2001 to 2015 (b = .67, p<.001). When couples exhibited more conflictual interactions in 2015, husbands generally reported a decrease in physical health two years later (Husbands: b = −.12, p<.05), while wives reported an increase in loneliness (b = .12, p<.05). From 2015 to 2017, there was considerable rank order stability for both loneliness (Husbands: b = .73, p<.001; Wives: b = .65, p<.001) and physical health (Husbands: b = .85, p<.001; Wives: b = .74, p<.001). Lastly, we considered mutual influences between loneliness and physical health for both husbands and wives. That is, because we controlled for previous levels of loneliness and physical health in 2015, we were able to assess the change in loneliness and physical health during later adulthood from 2015 to 2017 (i.e., cross-lags between loneliness and physical health). After controlling for wives’ physical health in 2015, wives who reported more loneliness in 2015 experienced a significant decline in their physical health in 2017 (b = −.35, p<.001). Other cross-lags between physical health and loneliness were not statistically significant, suggesting that loneliness is more consequential for physical health than physical health is for loneliness in later years. (Note: For model parsimony, these non-significant paths were removed from the final model.)

Within the model, statistically significant correlations were also noted (not shown in Figure 2). For instance, at each time point, physical health and loneliness were allowed to correlate. These correlations were generally not statistically significant. For instance, in 2017, the correlation between physical health and loneliness for husbands and wives was −.01 and −.02, respectively. In their mid-later years (2001), conflictual marital interactions were negatively correlated with husbands’ and wives’ physical health (r = −.11, p<.01 for both genders). Although these correlations between conflictual marital interactions and husbands’ and wives’ physical health were not statistically significant in 2015 (r = .01 and −.01, respectively), conflictual interactions were related to their reports of loneliness (.06, p<.01 and .14, p<.001, respectively).

Equality constraints were utilized in a supplementary analysis to further assess the rank order stability found for physical health (from 2001 to 2015 and again from 2015 to 2017) and loneliness (from 2015 to 2017). First, equality constraints assessed gender differences in the rank order stability. When these paths testing rank order stability were constrained to be equal for men and women, the change in chi-square (Δχ2) did not suggest a poorer model fit, indicating that, in general, the continuity in physical health and loneliness is similar for men and women. Equality constraints were also utilized to determine if the stability noted for physical health from the mid-later years to later adulthood (2001 to 2015) varied significantly from the stability noted during later adulthood (2015 to 2017). As expected, given the variation in time between assessments (15 years and then two years), the rank order stability was significantly greater for both husbands and wives during later adulthood (2015) (compared to variation from the mid-later years to later adulthood; 2001–2015) (Δχ2 = 101.96, Δdf 1; Δχ2 = 101.60, Δdf 1).

The Sobel test examined the statistical significance of the indirect effects linking conflictual marital interactions and physical health in husbands’ and wives’ mid-later years (2001) to their loneliness and physical health at the second time point in later adulthood (2017). Results indicated five statistically significant indirect effects and two additional effects that were marginally significant. Couples’ conflictual interactions were linked to wives’ loneliness and physical health in 2017 through their perception of loneliness in 2015 (b = 2.12, p<.05 and b = 2.54, p<.01, respectively). Conflictual marital interactions in the mid-later years were also indirectly linked to husbands’ loneliness in 2017 through their loneliness in 2015 (b = 2.99, p<.01). The two other statistically significant indirect effects were found for wives’ physical health in their mid-later years with indirect associations to wives’ loneliness in 2017 through their 2015 reports of loneliness (b = 4.10, p<.001) and to wives’ physical health in 2017 through loneliness in 2015 (b = 2.80, p<.01). The two marginally significant indirect effects linked couples’ conflictual interactions in mid-later years to husbands’ physical health and wives’ loneliness in later adulthood (2017) through destructive problem-solving behaviors in 2015 (b = 1.89, p = .06 for husbands’ physical health and b = 1.87, p = .06 for wives’ loneliness).

Discussion

Overall, the conceptual model drawn from the life-course stress-process perspective (Pearlin et al. 2005) was supported. Couples’ conflictual marital interactions in their mid-later years (2001) were related to both husbands’ and wives’ loneliness in later adulthood (2015) but not their physical health (2017) (Research Question 1). However, the non-significant effect of marital interactions on physical health may be at least partially due to our estimation of the influence of conflictual marital interactions on the residual change in physical health. There was a relatively high level of stability in physical health from mid-later years to later adulthood (B = .56 and .65 for wives and husbands, respectively), which reduces the variability in physical health scores that can be explained by conflictual interactions.

Conflictual marital interactions in later adulthood (2015) were related to wives’ increased loneliness and husbands’ physical health declines two years later (2017) (Research Question 2). This influence on husbands’ physical health supports the notion of increased health sensitivity to stressful life circumstances, particularly marital conflict later in the life course (Marmot et al., 2012). Moreover, the existence of effects on loneliness (particularly wives’ loneliness) stemming from previous conflictual interactions at two life stages (from 2001 to 2015 and 2015 to 2017) indicates that couples do not become “immune” or “numb” to the effects of conflictual marital interactions over time. This continued influence of conflictual marital interactions on both spouses is a demonstration of the “linked lives” of these continuously married couples (Bengtson et al., 2005). Elements of their marital relationship continue to influence each spouse’s outcomes across the life course.

Research Question 3, analyzing rank order stability in loneliness and physical health across later adulthood (2015 and 2017), stems from the life-course perspective’s emphasis on continuity in the developmental and social processes at play in individuals’ lives, particularly considering previous life stages (Elder & Giele, 2009). The current study found high rank order stability for husbands and wives loneliness and physical health across later adulthood with coefficients greater than .65. The high stability suggests that the rank order of physical health and loneliness are relatively fixed by the early years of later adulthood, which supports the notion that intervention and prevention efforts targeting these characteristics may be more effective when they target earlier life stages. However, despite this stability, as previously discussed, conflictual marital interactions were related to changes in wives’ loneliness and husbands’ health. The existence of these influences given the high rank order stability in physical health and loneliness is consistent with previous research noting that there is at least some opportunity to modify older adults’ experiences of poor physical health and loneliness (Marmot et al., 2012; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001). Moreover, these findings indicate that conflictual marital interactions play an important role in accounting for this variation. Therefore, at minimum, intervention and prevention efforts targeting older adults in enduring marriages should account for the marital context. Efforts intended to improve physical health and reduce loneliness may be most effective when they are purposeful in their aim to improve marital interactions.

The final research question of the current study addressed mutual influences between loneliness and physical health in later adulthood (2015 to 2017). Only one mutual influence was noted. Wives’ loneliness explained variation in their subsequent physical health after controlling for previous physical health. This influence was part of an indirect effect between wives’ physical health in mid-later years and their physical health several years into later adulthood through their loneliness in later adulthood. More importantly, the results provided evidence that the observed association between loneliness and physical health is not spurious due to the common influence of stressful marital interactions. This finding sheds light on how physical health and loneliness influence, and are influenced by, each other. By incorporating data from distinct life stages, these analyses demonstrating lagged influences also indicate that, in mid-later years, health influences loneliness, but, in later adulthood, loneliness influences health. Thus, adults with poor physical health in their mid-later years may be susceptible to feelings of loneliness in their later years, with loneliness serving as a powerful determinant of health in later years. This information is useful for developing interventions targeting specific life stages. Relatedly, interventions targeting decreased loneliness for older adults may prove beneficial for staving off further health declines.

Given previous literature noting associations between loneliness and physical health (e.g., Penninx et al., 1997), it was somewhat unexpected to find that in the SEM tested, contemporaneous correlations between physical health and loneliness were not statistically significant. In bivariate analyses (not shown), loneliness and health were related with weak to moderate associations (r in 2015 = −.19 and −.26, p<.01 for husbands and wives; r in 2017 = −.22 and −.27, p<.001). These findings highlight that interventions focusing solely on the link between physical health and loneliness may be over simplistic if they fail to consider important relational contexts, such as marital conflict, that may be driving both loneliness and physical health declines.

As with any study, these findings should be considered within the study limitations. First, the sample was comprised entirely of White couples in enduring marriages living in rural Iowa. Studies testing similar models with a more diverse population, such as multiple ethnicities and variation in length of marriage, are necessary. For example, some research suggests that marital processes, including marital interactions, vary across ethnicities, races, and cultures, in part because of the unique stressors faced (e.g., Marks et al., 2006). As such, research utilizing intersectional approaches is needed to acknowledge, and more fully understand, how diversities are intertwined with social institutions, such as marriage (Johnson & Loscocco, 2015). Second, self-reported information, particularly regarding physical health, may not capture nuanced detail regarding physical health and may also be a source of bias. Future research should extend this line of research using clinical measures of health outcomes. Third, there may be important covariates, such as husbands’ and wives’ health risk behaviors, that are external to the family system, or couple-level characteristics, such as couple religious participation, that shed further light on the processes identified in the current study. Fourth, we limited our analyses to couples in enduring marriages. The results may be different for people who experience divorce or marry later in life as they have less shared history with their partner. Fifth, due to the sample size, a fully recursive model considering all mutual influences between included constructs and all possible partner effects was not analyzed. More specifically, partner effects between loneliness and physical health were not estimated. While these paths were initially considered, they failed to reach statistical significance and worsened model fit. Consequently, they were removed from the final model. Larger samples may be better equipped to reveal such effects.

Regardless of these limitations, the current findings extend on existing knowledge to provide valuable insight on the associations between conflictual marital interactions, loneliness, and physical health during the mid-later years and later adulthood for couples in enduring marriages. Study findings emphasize stabilities in these constructs (and their associations) over 17 years while also demonstrating significant variations and factors that play a role in these changes over time.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research is currently supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (AG043599, Kandauda A. S. Wickrama, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, MH48165, MH051361), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724, HD051746, HD047573, HD064687), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ayalon L, Shiovitz-Ezra S, & Palgi Y (2013). Associations of loneliness in older married men and women. Aging & Mental Health, 17(1), 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Elder GH, & Putney NM (2005). The life course perspective on ageing: Linked lives, timing, and history. In Johnson ML (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of age and ageing (pp. 943–501). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, & Krishna A (2014). Social network epidemiology. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, & Glymour M (Eds.) Social Epidemiology (pp. 234–89). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J (2005). The role of marital quality in physical health during the mature years. Journal of Aging and Health, 17(1), 85–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1 Attachment. Basic Books. (Original work published 1969). [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Crawford LE, Ernst JM, Burleson MH, Kowalewski RB, … Berntson GG (2002). Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64, 407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, & Thisted RA (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Freedman VA, Cornman JC, & Schwarz N (2014). Happy marriage, happy life? Marital quality and subjective well-being in later life. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(5), 930–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, & Carstensen LL (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger R, & Elder GH (1994). Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T, & Dykstra PA (2006). Loneliness and social isolation. In Vangelisti A & Perlman D (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 485–500). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA, Van Tilburg TG, & De Jong Gierveld J (2005). Changes in adult loneliness. Research on Aging, 27, 725–747. [Google Scholar]

- Elder G, & Giele J (Eds.). (2009). The craft of life course research. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK, Taylor CB, Kraemer HC, & Agras WS (1991). High blood pressure and marital discord: Not being nasty matters more than being nice. Health Psychology, 10(3), 155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerst-Emerson K, & Jayawardhana J (2015). Loneliness as a public health issue: The impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, & Loscocco K (2015). Black marriage through the prism of gender, race, and class. Journal of Black Studies, 46(2), 142–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, & Shaver P (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, & Fagundes CP (2015). Inflammation: Depressive fans the flames and feasts on the heath. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 1075–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton T, Cacioppo JT, MacCallum RC, Glaser R, & Malarkey WB (1996). Marital conflict and endocrine function: Are men really more physiologically affected than women? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Cacioppo JT, MacCallum RC, Snydersmith M, Kim C, & Malarkey WB (1997). Marital conflict in older adults: Endocrinological and immunological correlates. Psychosomatic Medicine, 59(4), 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Ricker D, George J, Messick G, Speicher CE, Garner W, et al. (1984). Urinary cortisol levels, cellular immunocompetency, and loneliness in psychiatric inpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine, 46, 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Wilson SJ (2017). Lovesick: How couples’ relationships influence health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 421–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korporaal M, Broese van Groenou MI, & van Tilburg TG (2008). Effects of own and spousal disability on loneliness among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 20, 306–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TK, Wickrama KAS, & O’Neal CW (2019). Midlife general psychopathology trajectories and later-life physical health in husbands and wives. Health Psychology, 38(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luanaigh CÓ, & Lawlor BA (2008). Loneliness and the health of older people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(12), 1213–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Hawkley LC, Waite LJ, & Cacioppo JT (2012). Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 907–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, & Sugawara HM (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Marks L, Nesteruk O, Hopkins-Williams K, Swanson M, & Davis T (2006). Stressors in African American marriages and families: A qualitative exploration. Stress, Trauma, and Crisis, 9, 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, & Goldblatt P (2012). WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. The Lancet, 380, 1011–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LG, & Schoeni RF (2014). Trends in disability and related chronic conditions among the forty-and-over population: 1997–2010. Disability and Health Journal, 7(1), S4–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York academy of sciences, 840(1), 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Chen E, & Cole SW (2009). Health psychology: Developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 501–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KL, & Wong EH (2001). Loneliness in marriage. Family Therapy, 28, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal CW, Lucier-Greer M, Mancini JA, Ferraro AJ, & Ross DB (2016). Family relational health, psychological resources, and health behaviors: A dyadic study of military couples. Military Medicine, 181(2), 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, & Meersman SC (2005). Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, Van Tilburg T, Kriegsman DM, Deeg DJ, Boeke AJP, & van Eijk JTM (1997). Effects of social support and personal coping resources on mortality in older age: The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. American journal of epidemiology, 146(6), 510–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, & Covinsky KE (2012). Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172, 1078–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, & Sorensen S (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23, 245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, & McGinn MM (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 140–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, & Ferguson ML (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(3), 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabey AK, Rauer AJ, & Jensen JF (2014). Compassionate love as a mechanism linking sacred qualities of marriage to older couples’ marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(5), 594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JE (2017). Two-wave dyadic analysis of marital quality and loneliness in later life: Results from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. Research on Aging, 39(5), 635–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen JD, & Merikangas KR (2000). The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(2), 173–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theeke LA, Goins RT, Moore J, & Campbell H (2012). Loneliness, depression, social support, and quality of life in older chronically ill Appalachians. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 155–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(Supplement 1), S41–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston RC, & Kubzansky LD (2009). Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(8), 836–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ (2010). Understanding health disparities: The promise of the stress process model. In Avison WR, Aneshensel CS, Schieman S, & Wheaton B (Eds.) Advances in the conceptualization and study of the stress process (pp.3–21). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Victor C, Scambler S, Bond J, & Bowling A (2000). Being alone in later life: loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 10(4), 407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, O’Neal CW, Klopack ET, & Neppl TK (2018). Life course trajectories of negative and positive marital experiences and loneliness in later years: Exploring differential associations. Family Process, 59(10), 142–157. doi: 10.1111/famp.12410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, O’Neal CW, & Neppl TK (2018). Midlife family economic hardship and later life cardiometabolic health: The protective role of marital integration. The Gerontologist, 59(Spec No.2),. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]