Abstract

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumour occurring in the head and neck region. It is now understood that (human papillomavirus (HPV)- positive and HPV-negative diseases are two very different clinical entities associated with different outcomes. We decided to assess p16 expression status in patients with oropharyngeal cancer and retrospectively evaluate the outcomes of the treatment.

Material and methods

The evaluated group consisted of 98 consecutive patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx treated in a combined way in Holycross Cancer Centre in Kielce in 2006–2014. For all patients p16 status was assessed based on the biological material. In 51 patients HPV infection was diagnosed. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to produce survival curves using the log-rank test and the Cox proportional hazard model was used to determine the risk factors. The following risk factors were included: HPV status (positive, negative), sex, age, smoking, histopathological grade of the tumour, clinical stage, and systemic therapy application. For HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients independent analyses were done including aforementioned factors, excluding HPV status.

Results

The observation time for HPV-positive patients was significantly longer (p = 0.0008). Fifty-eight patients died, 40 patients are alive. Number of deaths in HPV-negative patients was statistically significantly higher (p = 0.0222). A statistically significant difference in the disease-free survival probability and overall survival probability between HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients was found (p = 0.0045 and p = 0.0037 respectively). For disease-free survival a statistically significant factor of the risk of recurrence was HPV infection (p = 0.0169). For HPV-positive patients, age (p = 0.0199) and smoking (p = 0.0353) were statistically significant risk factors of recurrence. For HPV-negative patients significant risk factors of recurrence were clinical stage (p = 0.0114) and systemic therapy application (p = 0.0271). For overall survival for the entire group statistically significant risk factors were absence of HPV infection (p = 0.0123), male sex (p = 0.0426), and age (p = 0.0311). For HPV-positive patients, age (p = 0.0096) and smoking (p = 0.0387) were statistically significant risk factors of death. For HPV-negative patients significant risk factors of death were clinical stage (p = 0.0120) and systemic therapy application (p = 0.0460).

Conclusions

Our data show that HPV infection is a predictor of better disease-free and overall survival in patients with oropharyngeal cancer. For HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer patients weekly given cisplatin with concurrent radiotherapy can be an alternative to three weekly given cisplatin considering effectiveness and early toxicity.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, head and neck cancer, radiochemotherapy

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumour occurring in the head and neck region, accounting for more than 90% of all cases [1]. The most commonly affected part of the head and neck mucosa is the oropharynx. Tobacco and alcohol abuse have been identified as important risk factors. Over the past decade, the importance of human papillomavirus (HPV) in the pathogenesis of oropharyngeal cancer has been recognized. The number of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer is increasing, mostly in young people [2–4]. The standard treatment for most patients with oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) is radiochemotherapy (RCH). Randomized studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that cisplatin-based concurrent radiochemotherapy regimens provide significantly higher response rates than radiotherapy alone [5–9]. The recommended treatment for stage III–IV head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is concurrent RCH of 70 Gy in daily fractions with cisplatin delivered every 3 weeks [10]. However, considering the toxicity of the treatment there is a possibility of using a lower dose of cisplatin which can be given weekly [11, 12]. Ang et al., in a phase III clinical trial from the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0129, first demonstrated that an HPV status of a tumour is a strong and independent prognostic factor for survival among patients with oropharyngeal cancer [13]. The findings from this study and others changed the understanding of HNSCC pathophysiology and treatment paradigms. It is now understood that HPV-positive and HPV-negative diseases are two very different clinical entities associated with vastly different outcomes [11–13]. We decided to assess p16 expression status, as the most recognized bio-marker of an HPV infection, in patients with OPC and evaluate the outcomes of treatment of patients with OPC.

Material and methods

The evaluated a group of 98 consecutive patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer treated in a combined way in The Holycross Cancer Centre in Kielce in 2006–2014. The characteristics of the group are shown in Table I. The analysed group included 18 (18.4%) women and 80 (81.6%) men. All patients were irradiated. The radiation therapy was administered using simultaneous integrated boost-intensity modulated radiotherapy technique at 2.0–2.2 Gy per fraction/5 days per week to 66–70 Gy in 30–35 fractions (84 patients), 10 patients received 60 Gy, and 4 patients received doses lower than 60 Gy (16–56 Gy) following their resignation. Twenty-three patients were operated on prior to irradiation. The surgical procedures consisted of cervical lymphadenectomy in 16 patients and local excision in 7 patients. Seventy-five patients received concomitant chemotherapy with cisplatin. The majority of them (68 patients) received cisplatin given weekly in a dosage of 40 mg/m2. Only 7 patients received cisplatin given every 3 weeks. Patients received the proper hydration before and after cisplatin administration. Early toxicity of radiochemotherapy was acceptable and was not a reason for the prolongation of the treatment in most cases. We did not observe renal complications in patients who received cisplatin (Table II). Patients who were not eligible for chemotherapy were treated with exclusive radiation therapy. The observation of the patients was terminated on 31st May 2018.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of studied group of patients along with the division into HPV+ and HPV–

| Factor | Entire group n (%) | HPV+ n (%) | HPV– n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | 98 (100) | 50 (51) | 48 (49) | – |

| Sex: | ||||

| Women | 18 (18.4) | 14 (28) | 4 (8.3) | 0.0124 |

| Men | 80 (81.6) | 36 (72) | 44 (91.7) | |

| Age [years]: | ||||

| Min.–max. | 31–79 | 31–75 | 37–79 | 0.3411 |

| Mean (SD) | 57 (9) | 57 (9) | 56 (8) | |

| Smoking: | ||||

| Yes | 57 (58.2) | 25 (50) | 32 (66.7) | 0.0962 |

| No | 41 (41.8) | 25 (50) | 16 (33.3) | |

| Grade: | ||||

| G1 | 12 (12.2) | 4 (8) | 8 (16.2) | 0.1700 |

| G2 | 70 (71.4) | 35 (70) | 35 (72.9) | |

| G3 | 16 (16.3) | 11 (22) | 5 (10.4) | |

| Clinical stage: | ||||

| I | 4 (4.1) | 1 (2) | 3 (6.2) | 0.7445 |

| II | 13 (13.3) | 7 (14) | 6 (12.5) | |

| III | 22 (22.4) | 12 (24) | 10 (20.8) | |

| IV | 59 (60.2) | 30 (60) | 29 (60.4) | |

| Surgery: | ||||

| Yes | 23 (23.5) | 13 (26) | 10 (20.8) | 0.5481 |

| No | 75 (76.5) | 37 (74) | 38 (79.2) | |

| Systemic therapy: | ||||

| Yes | 74 (75.5) | 39 (78) | 35 (72.9) | 0.5606 |

| No | 24 (24.5) | 11 (22) | 13 (27.1) | |

Table II.

Characteristics of early toxicity (WHO classification) in studied group of patients along with the division into HPV+ and HPV–

| Toxicity | Entire group n (%) | HPV+ n (%) | HPV– n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red blood cells: | ||||

| Grade 0 | 84 (86) | 44 (88) | 40 (83) | 0.3890 |

| Grade 1 | 13 (13) | 5 (10) | 8 (17) | |

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Grade 3 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| White blood cells: | ||||

| Grade 0 | 67 (69) | 33 (66) | 34 (71) | 0.9023 |

| Grade 1 | 16 (16) | 8 (16) | 8 (17) | |

| Grade 2 | 10 (10) | 6 (12) | 4 (8) | |

| Grade 3 | 5 (5) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | |

| Platelets: | ||||

| Grade 0 | 90 (92) | 46 (92) | 44 (92) | 0.3611 |

| Grade 1 | 5 (5) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | |

| Grade 2 | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (4) | |

| Grade 3 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Mucositis: | ||||

| Grade 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0.8514 |

| Grade 1 | 14 (14) | 7 (14) | 7 (15) | |

| Grade 2 | 71 (73) | 36 (70) | 37 (75) | |

| Grade 3 | 11 (11) | 7 (14) | 4 (8) | |

| Skin reaction: | ||||

| Grade 0 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0.9167 |

| Grade 1 | 34 (35) | 19 (38) | 15 (31) | |

| Grade 2 | 50 (51) | 24 (48) | 26 (54) | |

| Grade 3 | 12 (12) | 6 (12) | 6 (13) | |

Method of determination of p16 protein status

For all patients p16 status was assessed based on the biological material available in the Department of Pathology of Holycross Cancer Centre. In 51 patients HPV infection was diagnosed. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4 μm sections cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks. Immunostaining was carried out using a fully automated immunostainer (Ventana BenchMark Ultra XT), according to standard protocols. The primary antibodies were a mouse monoclonal primary antibody, CINtec p16 Histology, Ventana, Benchmark Roche (p16INK4a (E6H4)). Immunohistochemical staining results were interpreted by a specialist in pathology, devoid of knowledge of clinical data and histopathological results. The positive control tissues for CINtec p16 Histology were cervix cancer tissue and palate tonsil and a negative control was performed by omitting the primary antibody. The expression of p16 was categorized into four groups based on the distribution and proportions of cells with positive nuclear/cytoplasmic staining, as follows: 0 = negative; 1+ = 1% to 25% of cells positive; 2+ = 26% to 50%; 3+ = 51% to 75%; 4+ = 76% to 100%. For an undergoing analysis, cases were divided into two groups: positive (1 to 4+) and negative (0) reaction.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables have been presented in the form of the mean and standard deviation and the variables of the categorical type have been presented as a number. Student’s t-test was used to determine the diversity of age in tested groups. A χ2 test was used to assess the significance of diversity in a single classification and to assess the relationship between two classification factors. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to produce survival curves using the log-rank test and the Cox proportional hazard model was used to determine the risk factors. The method ENTER and FORWARD was applied to determine how independent variables are entered into the model (ENTER method – all variables are entered in the model in one single step, without checking; FORWARD method – significant variables are entered sequentially).

Statistical significance was determined as α < 0.05. The calculations were done using MedCalc Statistical Software version 18.5 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; http://www.medcalc.org; 2018).

Results

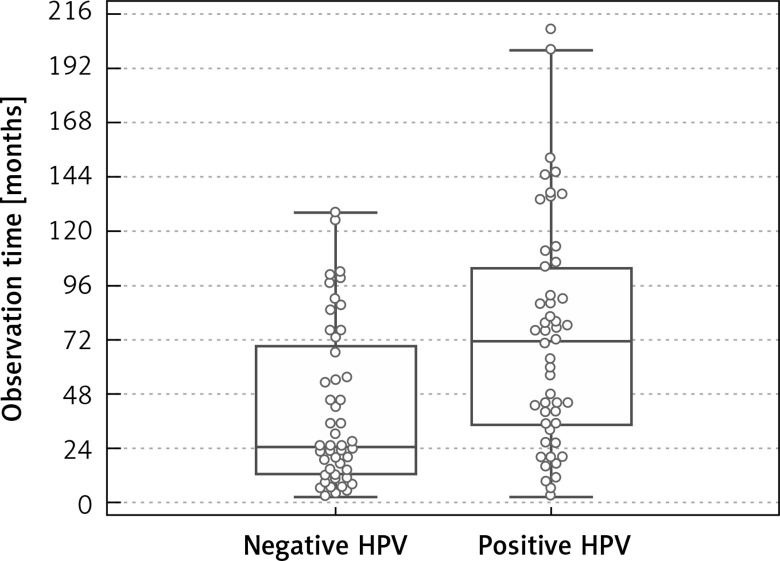

The total observation time for human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (HPVPOPC) patients was from 3 to 209 months, median 44 months, while for human papillomavirus-negative oropharyngeal cancer (HPVNOPC) the observation time was from 3 to 128 months, median 25 months. The observation time for HPVPOPC patients was significantly longer (p = 0.0008) (Figure 1). Fifty-eight patients died, 40 patients are alive. In the HPVPOPC group 24 (41.4%) patients died, while in the HPVNOPC group 34 (58.6%) patients died. The number of deaths in HPVNOPC patients was statistically significantly (p = 0.0222) higher. Twenty-nine patients died due to locoregional recurrence or progression. Distant metastases were observed in 8 patients (4 in lungs, 3 in liver, 1 in liver and bones), in 3 patients locoregional recurrence and distant metastases were the cause of death. In 11 patients another kind of cancer was found and in 9 cases was the reason of death (4 – lung cancer, 2 – oesophagus cancer, 1 – colon cancer, 1 – pancreas cancer, 1 – malignant lymphoma). One patient died because of human immunodeficiency virus infection complications. In 8 patients who died, the reason of death was not determined (Table III).

Figure 1.

Observation time in studied group of patients along with the division into HPV+ and HPV–

Table III.

Causes of death in studied group of patients along with the division into HPV+ and HPV–

| Cause of death | Entire group n (%) | HPV + n (%) | HPV– n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 58 (100) | 24 (100) | 34 (100) |

| Locoregional recurrence | 29 (50) | 9 (38) | 20 (59) |

| Locoregional recurrence and dissemination | 3 (5) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) |

| Dissemination | 8 (14) | 4 (17) | 4 (12) |

| Second cancer | 9 (16) | 5 (21) | 4 (12) |

| Unknown | 8 (14) | 4 (17) | 4 (12) |

| HIV complications | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| P-value | 0.5167 |

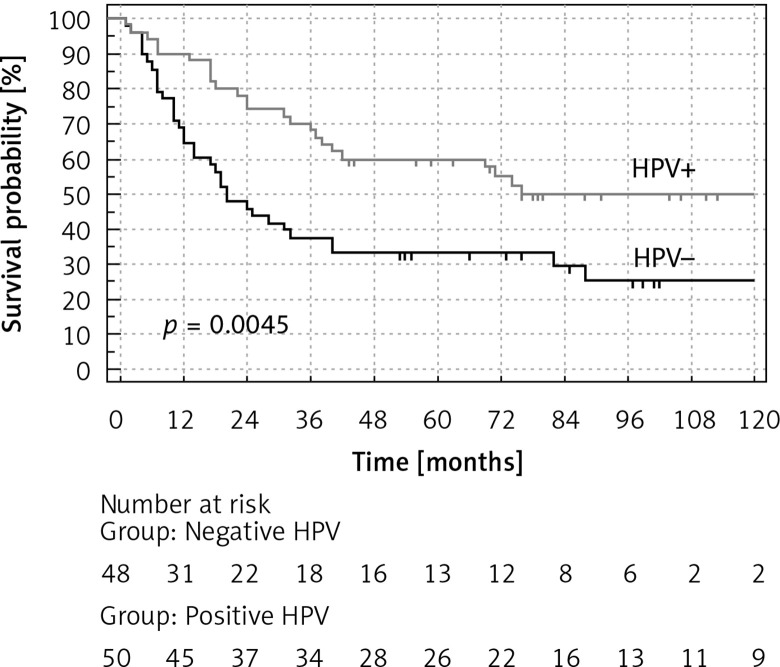

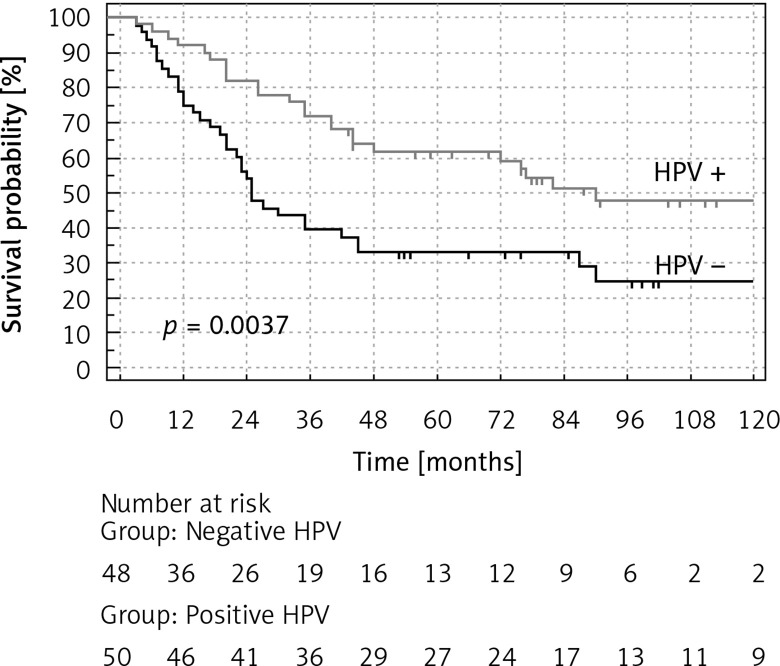

A statistically significant difference in the disease-free survival (DFS) probability and overall survival (OS) probability (p = 0.0045 and p = 0.0037 respectively), between HPV-positive vs. HPV-negative patients, was found (Figures 2, 3). HPV-positive patients had longer DFS and OS. The difference in favour of HPV-positive patients for DFS was 22% and 23% after 5 and 10 years respectively and for OS 29% and 23% after 5 and 10 years respectively (Table IV).

Figure 2.

Disease-free survival (DFS) probability (%) of patients with oropharyngeal cancer with the division into HPV+ and HPV–

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) probability (%) of patients with oropharyngeal cancer with the division into HPV+ and HPV–

Table IV.

Probability of disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in studied group of patients along with the division into HPV+ and HPV– in the observed intervals of 12, 24, 60, 120 months

| Observation intervals [months] | DFS | OS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV+ (%) (95% CI) | HPV– (%) (95% CI) | Difference (%) | HPV+ (%) (95% CI) | HPV– (%) (95% CI) | Difference (%) | |

| 12 | 90 (77–95) |

69 (53–79) |

21 | 92 (80–96) |

77 (62–86) |

15 |

| 24 | 75 (61–85) |

48 (44–71) |

27 | 82 (68–90) |

56 (41–68) |

26 |

| 60 | 55 (44–71) |

33 (13–40) |

22 | 62 (46–73) |

33 (20–46) |

29 |

| 120 | 49 (34–62) |

26 (13–40) |

23 | 49 (31–61) |

26 (13–40) |

23 |

| P-value | 0.0045 | 0.0037 | ||||

A multivariate analysis of risk factors affecting recurrence and mortality according to the Cox proportional hazard regression was done for the whole group. The following risk factors were included: HPV status (positive, negative), sex, age, smoking, histopathological grade of the tumour, clinical stage, and systemic therapy application. For HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients independent analyses were done including aforementioned factors, excluding HPV status. The results are presented in the Tables V and VI.

Table V.

Assessment of risk factors for recurrence of disease in multivariate Cox regression model. The ENTER and FORWARD methods were used

| Factor | Entire group | HPV+ | HPV– | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENTER | FORWARD | ENTER | FORWARD | ENTER | FORWARD | ||||||

| HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | |

| HPV (yes, no) | 1.95 1.12–3.35 | 0.016 | 1.76 1.03–3.01 | 0.037 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sex (F, M) | 2.53 0.97–6.56 | 0.055 | 2.94 1.15–7.51 | 0.023 | 2.27 0.63–8.15 | 0.207 | Not included | 1.72 0.38–7.68 | 0.475 | Not included | |

| Age [years] | 1.02 0.99–1.06 | 0.074 | Not included | 1.04 0.99–1.09 | 0.099 | 1.04 1.00–1.08 | 0.019 | 0.97 0.93–1.02 | 0.409 | Not included | |

| Smoking (yes, no) | 1.43 0.78–2.60 | 0.236 | Not included | 2.48 0.80–7.62 | 0.112 | 2.53 1.06–6.00 | 0.035 | 1.29 0.59–2.79 | 0.515 | Not included | |

| Grade | 0.90 0.53–1.52 | 0.716 | Not included | 0.97 0.48–1.94 | 0.937 | Not included | 0.78 0.36–1.68 | 0.535 | Not included | ||

| Clinical stage | 1.34 0.94–1.90 | 0.096 | Not included | 0.83 0.42–1.64 | 0.603 | Not included | 1.85 1.15–3.00 | 0.011 | 1.90 1.17–3.07 | ||

| Systemic therapy | 0.87 0.44–1.73 | 0.697 | Not included | 1.66 0.54–5.04 | 0.367 | Not included | 0.33 0.12–0.88 | 0.027 | 0.41 0.18–0.94 | ||

Table VI.

Assessment of risk factors for death in multivariate Cox regression model. The ENTER and FORWARD methods were used

| Factor | Entire group | HPV+ | HPV– | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENTER | FORWARD | ENTER | ENTER | FORWARD | |||||||

| HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | |

| HPV (yes, no) | 2.02 1.16–3.49 | 0.012 | 2.08 1.21–3.58 | 0.007 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sex (F, M) | 2.68 1.03–6.98 | 0.042 | 2.94 1.15–7.52 | 0.023 | 2.62 0.73–9.39 | 0.137 | Not included | 1.76 0.39–7.91 | 0.459 | Not included | |

| Age [years] | 1.03 1.00–1.06 | 0.031 | 1.03 1.00–1.06 | 0.009 | 1.04 0.99–1.09 | 0.074 | 1.05 1.01–1.09 | 0.009 | 0.99 0.94–1.03 | 0.712 | Not included |

| Smoking (yes, no) | 1.35 0.74–2.47 | 0.320 | Not included | 2.44 0.79–7.54 | 0.119 | 2.48 1.04–5.87 | 0.038 | 1.12 0.51–2.43 | 0.773 | Not included | |

| Grade | 0.90 0.53–1.54 | 0.726 | Not included | 0.94 0.46–1.91 | 0.874 | Not included | 0,77 0.34–1.72 | 0.525 | Not included | ||

| Clinical stage | 1.36 0.96–1.94 | 0.078 | 1.43 1.03–2.00 | 0.031 | 0.82 0.40–1.67 | 0.601 | Not included | 1.85 1.14–3.00 | 0.012 | 1.92 1.19–3.12 | |

| Systemic therapy | 0.88 0.44–1.75 | 0.728 | Not included | 1.58 0.52–4.79 | 0.414 | Not included | 0.36 0.13–0.98 | 0.046 | 0.39 0.17–0.89 | ||

For disease-free survival, using the ENTER method for the entire group, a statistically significant factor of the risk of recurrence was HPV infection (p = 0.0169) in a way that HPV-negative patients had twice as high risk of recurrence (HR = 1.95) in comparison to HPV-positive patients. However, the FORWARD method showed that significant risk factors of recurrence were the absence of HPV infection (HR = 1.77; p = 0.0370) and male sex (HR = 2.95; p = 0.0236).

For HPV-positive patients using the ENTER method statistically significant risk factors were not obtained, but the FORWARD method revealed that age (HR = 1.05; p = 0.0199) and smoking (HR = 2.53; p = 0.0353) were statistically significant risk factors of recurrence.

For HPV-negative patients using the ENTER method statistically significant risk factors were clinical stage (HR = 1.86; p = 0.0114) and systemic therapy application (HR = 0.33; p = 0.0271). Similarly, using the FORWARD method the results were as follows: clinical stage (HR = 1.90; p = 0.0085) and systemic therapy application (HR = 0.42; p = 0.0359). It can be concluded that risk of recurrence of HPV-negative patients almost doubles with every clinical stage, and decreases by 70% in patients subjected to chemotherapy.

For overall survival for the entire group with the ENTER method statistically significant risk factors were: the absence of HPV infection (HR = 2.02; p = 0.0123), male sex (HR = 2.69; p = 0.0426) and age (HR = 1.04; p = 0.0311). Using the FORWARD method, besides the above-mentioned factors, i.e. absence of HPV infection (HR = 2.09; p = 0.0074), male sex (HR = 2.95; p = 0.0237), and age (HR = 1.04; p = 0.0093), also clinical stage was significant (HR = 1.43; p = 0.0310).

For HPV-positive patients using the ENTER method statistically significant risk factors were not obtained, but the FORWARD method revealed that age (HR = 1.05; p = 0.0096) and smoking (HR = 2.48; p = 0.0387) were statistically significant risk factors of death.

For HPV-negative patients using the ENTER method statistically significant risk factors of death were clinical stage (HR = 1.86; p = 0.0120) and systemic therapy application (HR = 0.37; p = 0.046). Similarly, using the FORWARD method the results were as follows: clinical stage (HR = 1.93; p = 0.0075) and systemic therapy application (HR = 0.39; p = 0.0262).

Discussion

The discovery of the role of infection of the human papillomavirus in etiopathogenesis of head and neck cancer and the proof of prognostic and predicted value of the infection were among the highest achievements of contemporary oncology [5–7]. In an analysed group there were ninety-eight consecutive patients diagnosed and treated in the Holycross Cancer Centre. In all of them the p16 status was established [14]. In our group, in more than half of the patients an infection was present. The mean age of patients in both groups was similar. The HPV-related OPC is associated with the reduction of death [15–19]. Recent studies indicate that the expression of HPV-associated p16 in HNSCC is correlated with a better prognosis and improved response to conventional radiotherapy [20–23]. According to some studies, HPV status of tumours is associated with response to treatment and survival rates. Numerous studies have documented the effect of human papilloma virus on aetiology of oropharyngeal carcinomas. Especially, there are many publications about HPV-16’s correlation with base of tongue and oropharyngeal cancers [24–26]. Many studies have revealed a better survival rate among patients who are HPV positive. Kanyilmaz et al. [27] reported that tumour positivity for p16 was correlated with improved disease-free survival and overall survival.

Based on the analysis of our group of patients we have reached similar conclusions. An HPV infection predicted longer disease free-survival and overall survival rates for patients with OPC, which was also proven in our study. HPV-related cancers occur mostly in young people and are not strictly connected with smoking but with sexual behaviours. Our data showed that among the HPV-positive OPC patients there were smokers also, but the number was lower than in the HPV-negative group. In a multivariate analysis for HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients we found that HPV-positive patients who smoke have over two-fold higher risk of death than in non-smokers. Similar conclusions have been reported by other authors [28, 29]. The therapeutic decisions were based on current Polish recommendations [30]. In some cases, surgery was used, mainly concerning the removal of the cervical lymph nodes. The implementation of a surgical treatment in stage III–IV OPC is a point of controversy. The surgery is recommended for early stages and in limited disease mostly in patients with cancer of the palatine tonsil [28]. Application of upfront surgical treatment can lead to the delay of the treatment of choice, namely radiochemotherapy. Doses of radiotherapy for OPC patients were determined and were used in the analysed group. The implementation of radiochemotherapy for head and neck cancer patients drastically improved the outcomes of the treatment [31, 32]. Cisplatin is one of the most commonly used and best-studied drugs. Treatment with a single-agent bolus of cisplatin every 3 weeks at a dose of 100 mg/m2 is accepted as a standard regimen. However, this regimen is associated with significantly acute and late adverse events such as mucositis, haematological complications, and renal complications. Additionally, the completion rate for this regimen is relatively poor. Therefore, splitting 3-weekly cisplatin into a weekly cisplatin schedule might decrease toxicities and increase compliance. Several studies have suggested that radiochemotherapy with a weekly cisplatin regimen might be successful for treatment of locally advanced HNSCC [11, 33–35]. In our group, eligible patients received this kind of treatment. The majority of patients in our group received weekly given cisplatin in the dose of 40 mg/m2. The decision of using cisplatin weekly was connected with our own experience, but the majority of our patients received 200 mg/m2. The importance of using chemotherapy for OPC patients is critical. It is important for HPV-negative OPC, which we proved in our study. Most patients with head and neck cancer are smokers and alcohol drinkers. It is directly connected with cardiovascular and pulmonary disorders. In our group there were 8 deaths not directly connected with OPC, but apparently with associated disorders. In some cases another incidence of cancer was diagnosed and in most cases it was the cause of death.

In conclusion, our data show that HPV infection is a predictor for better disease-free and overall survival in patients with oropharyngeal cancer. The total observation time is longer than 10 years for HPV-positive OPC patients. For these patients weekly given cisplatin with concurrent radiotherapy can be an alternative to three weekly given cisplatin considering effectiveness and early toxicity.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Schiff BA. Overview of Head and Neck Tumors – Tumors of the Head and Neck. Merck Manual Professional Version; Available at: www.msdmanuals.com. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Syrjanen S. Human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck cancer. J Clin Virol. 2005;32(Suppl 1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasman A, Attner P, Hammersted L, et al. Incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive tonsillar carcinoma in Stockholm, Sweden: an epidemic of viral-induced carcinoma? Int J Cancer. 2009;125:362–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Psyrri A, Di Maio D. Human papillomavirus in cervical and head-and-neck cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;5:24–31. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Rorke MA, Ellison MV, Murray LJ, Moran M, James J, Anderson LA. Human papillomavirus related head and neck cancer survival: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:1191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tribius S, Ihloff AS, Rieckmann T, Petersen C, Hoffmann M. Impact of HPV status on treatment of squamous cell cancer of the oropharynx: what we know and what we need to know. Cancer Lett. 2011;304:71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marur S, Burtness B. Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treatment: current standards and future directions. Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26:252–8. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pignon JP, Le Maitre A, Maillard E, Bourhis J. MACH-NC Collaborative Group: meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomized trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denis F, Garaud P, Bardet E, et al. Final results of the 94-01 french head and neck oncology and radiotherapy group randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone with concomitant radiochemotherapy in advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:69–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban D, Corry J, Solomon B, et al. Weekly cisplatin and radiotherapy for low risk, locoregionally advanced human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1117–21. doi: 10.1002/hed.24169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driessen CM, Janssens GO, Van Der Graaf WT, et al. Toxicity and efficacy of accelerated radiotherapy with concurrent weekly cisplatin for locally advanced head and neck carcinoma. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E559–65. doi: 10.1002/hed.24039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis JS, Jr, Thorstad WL, Chernock RD, et al. p16-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: an entity with a favorable prognosis regardless of tumor HPV status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1088–96. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e84652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lassen P, Primdahl H, Johansen J, et al. Impact of HPV-associated p16 expression on radiotherapy outcome in advanced oropharynx and non oropharynx cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014;113:310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rischin D, Young RJ, Fisher R, et al. Prognostic significance of p16INK4A and human papillomavirus in patients with oropharyngeal cancer treated on TROG 02.02 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4142–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus – positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Posner MR, Lorch JH, Goloubeva O, et al. Survival and human papillomavirus in oropharynx cancer in TAX 324: a subset analysis from an international phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1071–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dayyani F, Etzel CJ, Liu M, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of human papillomavirus (HPV) on cancer risk and overall survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lassen P, Eriksen JG, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Tramm T, Alsner J, Overgaard J. Effect of HPV-associated p16INK4A expression on response to radiotherapy and survival in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1992–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Licitra L, Perrone F, Bossi P, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus affects prognosis in patients with surgically treated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5630–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, et al. Prognostic significance of p16 protein levels in oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5684–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrelli F, Sarti E, Barni S. Predictive value of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 trials. Head Neck. 2014;36:750–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.23351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pintos J, Black MJ, Sadeghi N, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and oral cancer: a case-control study in Montreal, Canada. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:242–50. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tastekin E, Caloglu VY, Durankus NK, et al. Survivin expression, HPV positivity and microvessel density in oropharyngeal carcinomas and relationship with survival time. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:1467–73. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.56616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanyilmaz G, Ekinci O, Muge A, Celik S, Ozturk F. HPV-associated p16 INK4A expression and response to therapy and survival in selected head and neck cancers. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:253–8. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.1.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mirghami H, Leroy C, Chekourry Y, et al. Smoking impact on HPV driven head and neck cancer’s oncological outcomes? Oral Oncol. 2018;82:131–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biesaga B, Mucha-Małecka A, Janecka-Widła A, et al. Differences in the prognosis of HPV16-positive patients with squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck according to viral load and expression of P16. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144:63–73. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2531-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krzakowski M, Herman K, Jassem J, Jędrzejczak W, Kowalczyk JR, Podolak-Dawidziak M. Zalecenia postępowania diagnostyczno-terapeutycznego w nowotworach złośliwych u dorosłych. Gdansk: Via Medica; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, Designe L. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. Lancet. 2000;355:949–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcu L, Van Doorn T, Olver I. Cisplatin and radiotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Acta Oncol. 2003;42:315–25. doi: 10.1080/02841860310004364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:92–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho KF, Swindell R, Brammer CV. Dose intensity comparison between weekly and 3-weekly cisplatin delivered concurrently with radical radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a retrospective comparison from New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton, UK. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:1513–8. doi: 10.1080/02841860701846160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinmann D, Cerny B, Kartstens JH, Bremer M. Chemoradiotherapy with weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2 in 103 head- and-neck cancer patients: a cumulative dose-effect analysis. Strahlenther Onkol. 2009;185:682–8. doi: 10.1007/s00066-009-1989-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]