Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the world in ways not seen since the 1918–1920 Spanish Flu. Disinformation campaigns targeting health crisis communication during this pandemic seek to cripple the medical response to the novel coronavirus and instrumentalize the pandemic for political purposes. Propaganda from Russia and other factions is increasingly infiltrating public and social media in Ukraine. Still, scientific literature has only a limited amount of evidence of hybrid attacks and disinformation campaigns focusing on COVID-19 in Ukraine. We conducted a review to retrospectively examine reports of disinformation surrounding health crisis communication in Ukraine during the COVID-19 response. Based on the themes that emerged in the literature, our recommendations are twofold: 1) increase transparency with verified health crisis messaging and, 2) address the leadership gap in reliable regional information about COVID-19 resources and support in Ukraine.

Keywords: Health communication, Risk communication, Science and media

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically changed the world within a few short months. In addition to morbidity and mortalities, the pandemic has put a strain on healthcare systems, exposed weaknesses in government preparedness to deal with a pervasive health threat, changed the way millions of people work, and set economies on uncertain trajectories. The mixture of uncertainty, fear, and danger creates a perfect storm for disinformation, particularly in a time of social networks and instantaneous communication.

While all countries have been vulnerable to disinformation during the escalating COVID-19 pandemic, Ukraine’s experience is a particularly unique case that deserves special attention. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine, alongside the annexation of Crimea by Russia, has manifested as a hybrid war in which assaults are waged in many spheres beyond the traditional battlefield (Patel et al., 2020a). One aspect of this hybrid warfare is cyber and information warfare; in other words, disinformation campaigns.

The terms “disinformation” and “misinformation,” in the grey literature, are often used interchangeably without consideration or awareness of the nuanced difference between each other. Conceptually found in past research studies, disinformation has several theoretical foundations and lessons learned (Starbird et al., 2020). The Merriam-Webster dictionary (2020) defines disinformation as false information deliberately and often covertly spread (as by the planting of rumors) to influence public opinion or obscure the truth. On the other hand, from a more academic view, another definition of disinformation is described as deliberately false or misleading information with its purpose to not always to convince, but to instill doubt (Jack, 2017; Pomerantsev and Weiss, 2014). Although the descriptions of the two definitions of disinformation are very similar, the purpose of the spread of it varies. However, in accordance with the US Joint Dictionary, personnel within the DoD will use an accepted general definition from a credible dictionary (Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2020, p. 2). Therefore, this paper will use and refer to disinformation using the definition provided by the Merriam-Webster dictionary. Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information (Merriam-Webster, 2020). In other words, the term “disinformation” implies intentionality to spread false information to achieve a goal, whereas “misinformation” refers to incorrect information that may or may not be purposefully spread to mislead. Additionally, a search of relevant North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) doctrine, terminology, and publications indicates that the term “misinformation” is present in references but is not well defined. It is listed as a purpose of NATO communication to alleviate misinformation (NATO, 2017). Employed to mislead for a strategic, political purpose, actions arising from disinformation campaigns can create a hybrid type of warfare between countries.

Hybrid warfare and disinformation in Ukraine

Hybrid warfare, stemming from the conflict in East Ukraine, has established an ongoing presence of disinformation within Ukraine. Hybrid threats incorporate a full range of warfare tactics, including conventional means, acts of terrorism including indiscriminate violence and coercion, criminal disorder, and disruptive technologies or cyber security attacks to destabilize an existing order (Mosquera and Bachmann, 2016; NATO, 2019). These attacks can be waged by states or nonstate actors. Disinformation is an example of a hybrid warfare technique and encompasses a full spectrum of activities aimed at undermining legitimacy in communication, infrastructure, and political systems and economies. In essence, these campaigns seek to fracture or destabilize societies by any means necessary.

The mechanics of Russia’s hybrid tactics have been known for some time (NATO, 2019). Russian propaganda is based on a few core narratives, according to a report by Popovych et al. (2018). Overarching, basic, and intended to evoke emotional reactions, these narratives form the key structural elements of the broader disinformation campaigns. They interpret or skew real events to shape public opinion according to a political agenda. These aggressive cyber campaigns are waged across social media and infrastructure, and point to a full-spectrum conflict reaching far beyond Ukraine: Russia has contributed significantly to instability in many regions, including military intervention in Georgia and surrounding Baltic countries, the illegal annexation of Crimea, infiltration of United States elections, cyberattacks against Ukraine and bordering countries, alleged usage of chemical weapons in the United Kingdom and strategic manipulation of public opinion in media and social networks across the globe (Popovych et al., 2018).

Healthcare disinformation in Ukraine

Russian disinformation activities in Ukraine go beyond conventional pro-Russia propaganda; hybrid tactics in health communication have been growing for several years. For example, the Russian government has promoted anti-vaccination messaging abroad, (e.g., measles immunization programs), particularly in conflict-affected areas of Ukraine (Francis, 2018). This tactic aims to weaken the target societies and undermine trust in governmental institutions and health systems (Broniatowski et al., 2018). Such campaigns are often used by the Kremlin to fuel the polarization of society, thus destabilizing it from within and constituting a threat to national security (Harding, 2018).

Recent disinformation campaigns have focused on the COVID-19 pandemic (Gabrielle, 2020), aiming to cripple health crisis communication to weaken Ukraine’s response to the pandemic. Disinformation about the novel coronavirus and available resources are spread through coordinated and sophisticated cyber campaigns (HHS Cybersecurity Program, 2020). Despite best efforts to curtail these campaigns, as government and public health officials and institutions focus on containing the community spread of the virus and providing a quality response, disinformation is increasing (Talant, 2020). Nonetheless, only a limited amount of evidence is currently available in scientific literature to illustrate the hybrid attacks pertaining to the COVID-19 pandemic. Assessing the state of disinformation on COVID-19 is the first step in considering how to counter it and bolster Ukraine’s ability to respond to the pandemic.

Objective

In this paper, we carry out a review to systematically examine the messages surrounding health crisis communication in Ukraine during the COVID-19 outbreak. Our analysis seeks to canvas the ways disinformation about the novel coronavirus is being spread in Ukraine, so as to form a foundation for assessing how to mitigate the problem. How are “fake news” items being used to communicate the COVID-19 response in Ukraine? Given the global reach of disinformation campaigns, these insights may also be useful for other countries and regions of the globe where the COVID-19 pandemic is currently surging.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review to examine the reported messages, studies, and campaigns surrounding health crisis communication in Ukraine during the COVID-19 pandemic since first case occurred in Wuhan, China on December 31, 2019. Our search methodology included examining news articles, technical reports, policy briefs, and peer-review publications that include data on COVID-19 in Ukraine and the messaging about it. Our goal was to capture the existing knowledge about disinformation about coronavirus and medical responses to it, as discussed and covered in media news articles, policy briefs, technical reports, and peer-reviewed publications.

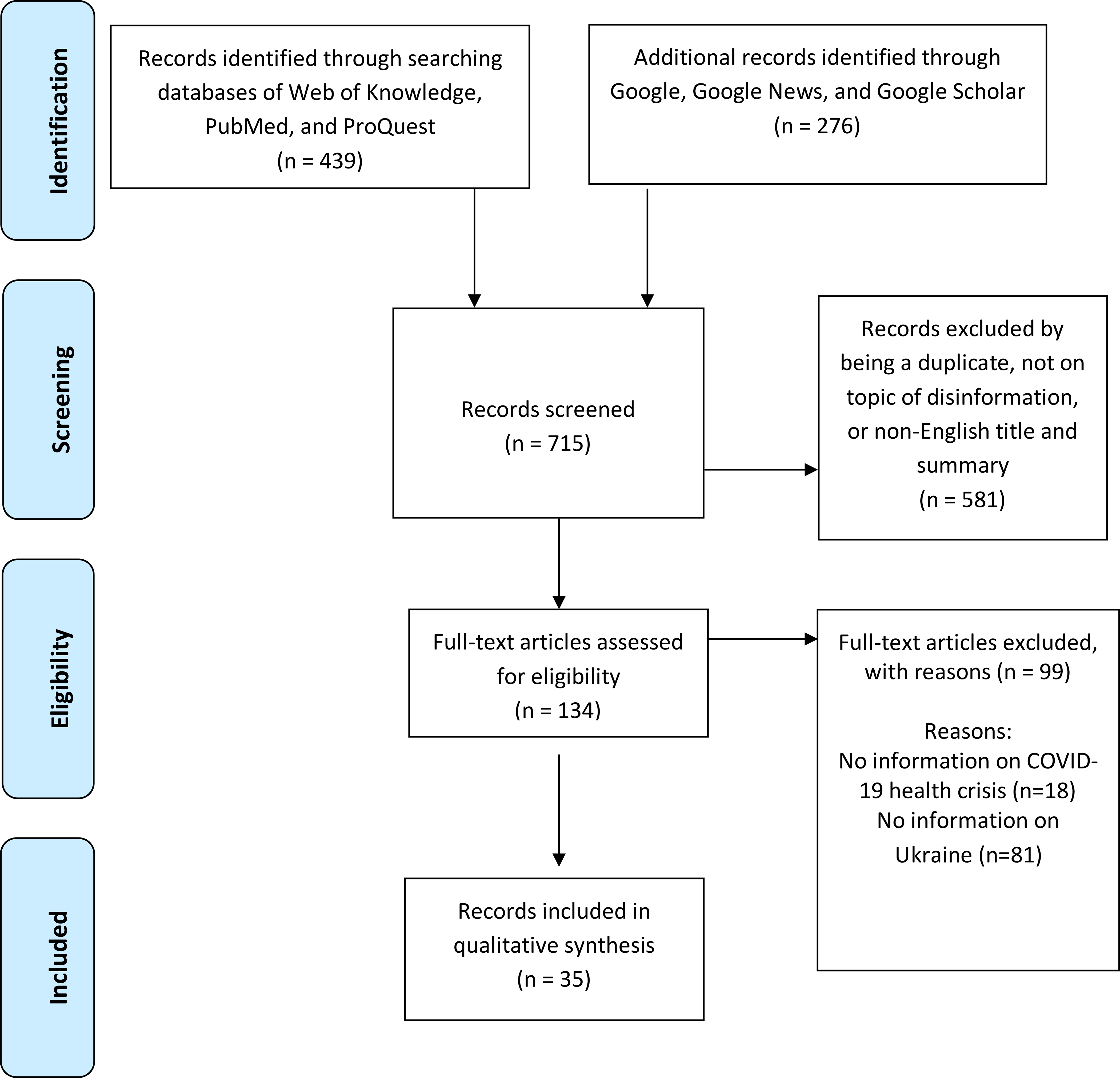

We used keyword searches in databases of Web of Knowledge (all databases), PubMed, ProQuest, Google News, Google, and Google Scholar (Figure 1). Ukraine’s media environment is modern, but many media organizations are owned or controlled by oligarchs or follow political agendas. There is also a hostile attitude towards many journalists in Eastern Europe; thus, many consider Ukraine’s media landscape a laboratory and ideal setting for hybrid warfare, disinformation, and information operations (Jankowicz, 2019). Because of this, we used two media news-focused databases (ProQuest and Google News) to capture a wide reach of information being shared, in addition to using interdisciplinary academic databases where scholarly peer-reviewed publications could be found on the topic. The following was the keyword strategy used:

COVID

Ukra*

Health*

Healthcare

Disinform*

Misinform*

Fake

Lie*

Media AND tru*

3 OR 4

5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9

1 AND 2 AND 10 AND 11

Searches were carried out from June 3 to 5, 2020, with a publication cutoff date of May 31, 2020. The search query used was the following: COVID AND Ukra* AND (Health* OR Healthcare) AND (Disinform* OR Misinform* OR Fake OR Lie* OR (Media AND tru*)). For any keyword searches with a high amount of volume, such as on Google (i.e. with over 200 pages of results), we reviewed the first 100 unique links after filtering to meet the inclusion criteria (see below). If two or more links came from the same main website or publication, this was considered one unique link. From the first 100 unique links, we extracted any publications (e.g. annual reports or educational handouts) that appeared relevant to the discussion of COVID-19 and health crisis communication for further examination. This search methodology for grey literature in Google databases was used in previous publications (Samet and Patel, 2011, 2013; Patel et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Search Strategy

To be included in the review, publications or documents had to: i) be found on Web of Knowledge, PubMed, ProQuest, Google News, Google, and/or Google Scholar; ii) be open access or accessible by Harvard University Library; iii) have a title and abstract/summary written in English; and iv) mention misinformation, fake news, disinformation, false information with COVID-19 pandemic or health crisis in Ukraine.

Both “misinformation” and “disinformation” were used as search terms. As noted above, the nuances of the terms are often missed or ignored in common literature. For the purposes of this systematic review, whether the authors of the literature understood the distinction between these terms and used them appropriately was not judged or considered cause for exclusion. In this article, we use the term “disinformation” throughout for simplicity and consistency; based on the definition given earlier, most authors were describing disinformation, and their choice of terminology is not important. Health crisis communication has been difficult to define in literature in terms of form or content (Quinn, 2018), so we used the definition of health or healthcare communication given by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to evaluate each potential publication for inclusion. CDC defines it as the “study and use of communication strategies to inform and influence decisions and actions to improve health” (CDC, 2020).

We designed an analytical spreadsheet to systematically extract data from the accepted literature. The following data were extracted: month and year of publication, type of reference, summary, and key takeaways. Data extraction was carried out by two authors and discussed between both authors for consistency. Thematic analysis was used to synthesize the data by coding it and organizing it into themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Results

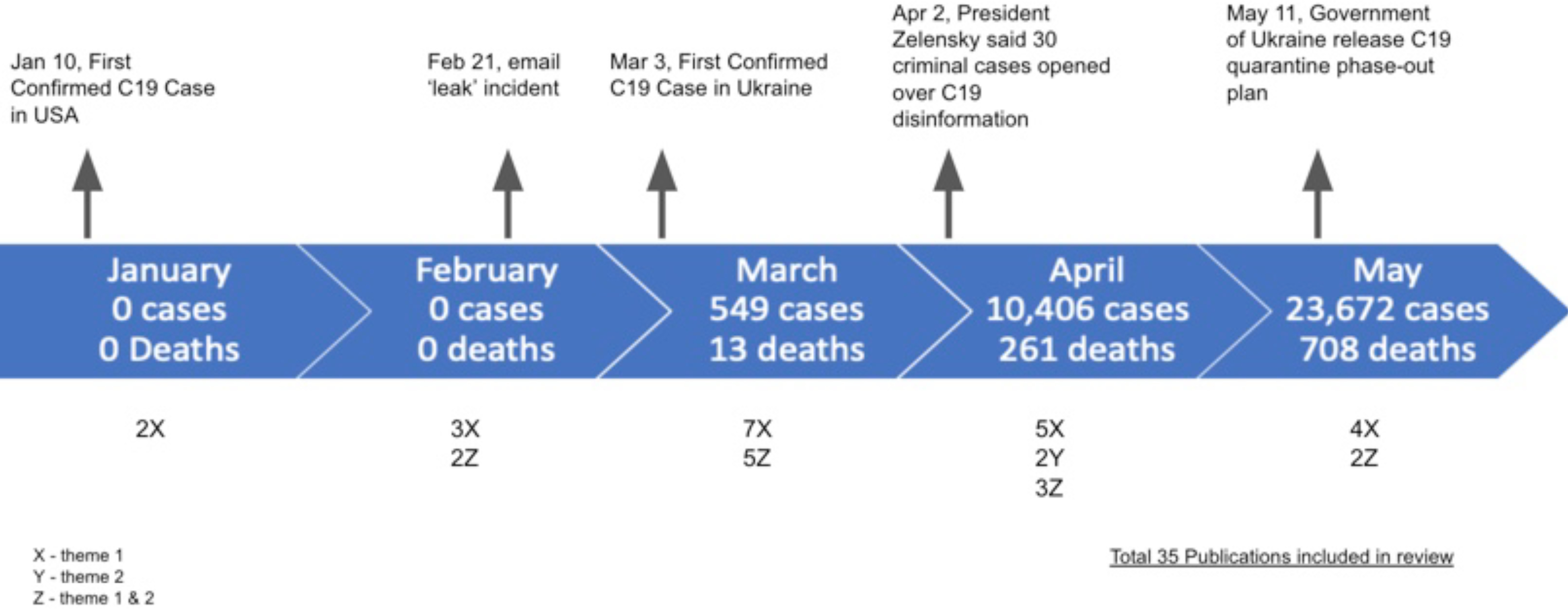

Through our search methodology strategy (Figure 1), we identified 715 texts published from January to May 2020 that contained information about COVID-19-related disinformation messaging in Ukraine. Of these, 134 were selected for full text read based on the title and summary reads. From full-text read, we retained documents that matched the inclusion criteria (listed in Table 1); our review included 35 documents comprising policy briefs, news articles, technical reports, and peer-reviewed publications. Thirty-four percent of the included publications were published in March 2020, which was a 500% increase from the number of the identified publications published in January 2020. From March to May 2020, there was a 50% decrease in publications included in this review, as seen in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Evidence table of records included in this review

| Date of Publication (sorted by oldest date first) | Citation | Type of Reference | Summary | Key Takeaways | Theme(s) 1. Trust and accuracy of message 2. Messages related to COVID-19 resources and support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 14 2020 | (Freelon & Lokot, 2020) | Journal article | A successful disinformation campaign promotes highly provocative opinions to a specific group of people to either provoke and sow discord within said group or to strengthen and galvanize their position in an echo chamber. The tweets and accounts studied show a high level of slander towards the opposite group. | Every hate and radical group can be infiltrated and influenced by disinformation. | 1 |

| Jan 14 2020 | (Wilson & Starbird, 2020) | Journal article | Study on the disinformation campaign launched by Russian backed Anti-White Helmets to make the White Helmets (volunteer rescue group in Syria) look bad. They noted that the Anti-White Helmets communications were streamlined across social media sites and showed high levels of coordination and execution, which implies they had more resources to broadcast their Anti-White Helmet messages across these channels. | Russia’s disinformation campaigns are complex and highly organized seen in Ukraine and Syria. They were successful in sowing public discord and distrust with a volunteer rescue group in Syria. | 1 |

| Feb 20 2020 | (Arciga, 2020) | News article | Article discusses the fake leaked email that caused a small town uproar and protest. | Highlights include direct effect of disinformation had on a small town in Ukraine and led to the assault of a bus carrying 2 COVID-19 patients to a hospital. | 1, 2 |

| Feb 20 2020 | (Miller, 2020b) | News article | Reviews what happened in Ukraine regarding the leaked email scandal and impact it had on government officials in the local city and province. Although they tried to speak out and clear out the disinformation, their words fell on deaf ears as the people were already scared and angry. | Using proper communication channels and issuing statements from the right people in power (i.e. governor, mayor) may still go unheard, in favor of the fearmongering disinformation. | 1, 2 |

| Feb 21 2020 | (Peters, 2020) | News article | Fake email was ‘leaked’ to public which led to mass protest | Disinformation can cause terror and violence. | 1 |

| Feb 21 2020 | (Polityuk & Zinets, 2020) | News article | Ukraine's prime minister speaks out against disinformation about COVID-19 pandemic | Disinformation campaigns led by Russian state media outlets are nothing new to Ukraine or Eastern European countries. | 1 |

| Feb 22 2020 | (Korybko, 2020) | News article | Article touches on email ‘leak’ and suggests media outlets need to become more responsible with information | When mainstream media is not fact checking sources, it helps the spread disinformation (intentional or not). | 1 |

| Mar 3 2020 | (Melkozerova & Parafeniuk, 2020) | News Article | Discusses what happened in the town in Ukraine impacted by the fake email leak from govt officials. | Nine officers were injured and 24 people were arrested after riots due to disinformation | 1,2 |

| March 5, 2020 | (Krafft & Donovan, 2020) | Journal article | A quantitative study carried out to observe how disinformation forms and spreads throughout the social media sphere. | Combatting disinformation is getting harder as now the forces that spread disinformation are streamlining their messages across different mediums. Also, echo chambers are organically created and become breeding grounds for further disinformation campaigns. | 1 |

| March 9 2020 | (Miller, 2020a) | News article | Article outlines what happened in the small town in Ukraine impacted by the fake email leak from government officials. | Incident shows the impact of disinformation campaigns on local and small governments. | 1, 2 |

| March 17 2020 | (Peel & Fleming, 2020) | News article | Article explains the aims of Kremlin disinformation campaigns as to aggravate the public health crisis, specifically by undermining public trust in national healthcare systems, and preventing an effective response to the outbreak. | The aims of these campaigns are to inflict "confusion, panic, and fear" and stop people from obtaining good information about the contagion. This may be part of a broader strategy to "subvert European societies from within” and overall European diplomacy. | 1 |

| March 18 2020 | (Emmott, 2020) | News article | EU releases a report stating the Kremlin is launching a disinformation campaign on them. Earliest date of disinformation was January 26, 2020. | Russia began its disinformation campaign in January 2020, possibly even before that. Campaign tried to weaponize the virus and blame the EU & US for deaths. | 1 |

| March 18 2020 | (Jozwiak, 2020b) | News article | Pro-Kremlin media outlets in Russia are spreading disinformation about COVID-19 pandemic to undermine the Western nations (EU, US, etc.) | Growing need is for a fact-checking tool for social media accounts. | 1 |

| March 19 2020 | (Wanat et al., 2020) | News article | Article alerts about findings from European Union’s diplomatic service about Russian online trolls which were spreading falsehoods about the coronavirus in Europe - using the health crisis “to sow distrust and division.” | “East StratCom office said it had collected 80 coronavirus-related disinformation cases on popular media channels in Europe since January 22.” | 1 |

| March 26 2020 | (EUvsDisinfo, 2020) | Review | Review summarizes the disinformation timeline in Ukraine and suggests the intention of those who are leading the disinformation campaigns. | Review documents first disinformation piece in Ukraine related to COVID-19 pandemic (1/22/20) and closely follows it to April. | 1, 2 |

| March 26 | (Tucker, 2020) | News article | Russia is leading anti-NATO/EU disinformation campaign in Eastern Europe countries | Russia continues to show an effort to undermine Eastern Europe countries and Western nations in the EU and USA. | 1 |

| March 27 2020 | (EURACTIV & Agence France-Presse, 2020b) | News article | Article lists examples of disinformation in Ukraine with regard to COVID-19 outbreak (i.e. vaccine released in water system, fake number of coronavirus cases in the country, and possible disinfectant spray released via helicopter) | Article displays the effects of disinformation campaigns and how easy it is to manipulate people when fear tactics are used with COVID-19 infodemic and lack of trust in the government. | 1,2 |

| March 28 2020 | (Barnes et al., 2020) | News article | Article describes the growing propaganda campaigns and their spread from government-linked social media accounts. | Official Russian government social media accounts contributed to the manifestation and spread of disinformation, not just media outlets. | 1, 2 |

| March 31 2020 | (Paul & Filipchuk, 2020) | News article | Article describes Ukraine's healthcare system and suggests how help will be needed from the EU. | Article lists examples of how COVID-19 pandemic will cripple the Ukrainian economy due to lack of testing and resources. | 1, 2 |

| April 2020 | (Sukhankin, 2020) | Policy brief | Article broadly discusses the ways and reasons why Russia spreads disinformation. | Article suggests that Russia has developed a habit of spreading disinformation about COVID-19 pandemic, in order to create chaos and to “crush the liberal world order” (p. 1) and establish themselves as the global powerhouse they once were pre-Soviet collapse. | 1 |

| April 1 2020 | (RFE/RL, 2020) | News article | EU published a statement informing that Russia and China are working together to spread disinformation to undermine EU's authority and credibility. More than 150 reports from Pro-Kremlin media outlets were reviewed. | Article confirms that Russia continues to spread disinformation about COVID-19 pandemic along with the goal of making the public not trust Western countries. | 1 |

| April 2 2020 | (BBC, 2020c) | News Article | Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said that 30 criminal cases have been opened over coronavirus disinformation. | National Guardsmen are also fighting false information about the virus along with online fraud and growing distribution of dubious-quality medical products related to COVID-19 response to the public consumers. | 2 |

| April 2, 2020 | (Borah, 2020) | News article | Article reviews President Trump’s comments and tweets about COVID-19 disease and discusses how his lack of urgency early on led to deliberate disinformation and further development of public mistrust. Mockery of news sources like CNN acts like its own disinformation campaign as well, which diminishes and devalues CNN reporting regardless if true or not. | Article informs that just like Russia, President Trump spreads disinformation about the virus to make people, at large, more ignorant of it. | 1 |

| Apr 8 2020 | (Ukraine Business Daily, 2020) | News article | European Commission will issue more than 190 million euros to Ukraine to combat the spread of the coronavirus infection, including combatting disinformation and strengthening the healthcare sector. | Urgent resources have been given by EU to stop the disinformation and healthcare needs with COVID-19 | 2 |

| April 8, 2020 | (Kosmehl, 2020) | Policy brief | Policy discussions on the geopolitical issues related to COVID-19 crisis show how China and Russia are in battle with the EU on being good players and to narratively win the hearts and minds of those most vulnerable. | COVID-19 crisis brings opportunity for health diplomacy in Eastern Europe with putting unity, credibility and capacity of European Union to test along with Russia and China growing in influence and supporters among vulnerable populations. | 1, 2 |

| Apr 20 2020 | (Lima, 2020) | News article | Article discusses disinformation campaigns that aimed to incite fear, aggression, and vandalism against the critical infrastructure and essential maintenance workers, specifically at weakening the crisis communication networks. | Article lists concerns of disinformation on SMS information services carrying the latest health recommendations and details of local health hotlines. Repurposed health and self-care apps are helping consumers with COVID-19-related health advice, factual websites, hotlines and other related media. | 1 |

| April 21 2020 | (Shea, 2020) | News article | Article discusses danger of Russia using pandemic as cover to increase pressure on Ukraine, describes insufficiencies in Russia’s healthcare system, describes Ukraine’s response as more decentralized, and calls for Western support for Ukraine. | Russia’s low case numbers may be more indicative of inadequate healthcare system than deliberate disinformation; Ukraine’s fate in battling the pandemic is important to the US’s foreign policy. | 1, 2 |

| April 22 2020 | (Jozwiak, 2020c) | News article | Russia, Iran, and China are leading an anti-EU disinformation campaign | More countries are starting to participate in spreading disinformation about the EU. | 1, 2 |

| April 23 2020 | (BBC, 2020a) | News Article | Ukrainian cyber police have blocked over 5,000 internet links and identified 284 people spreading disinformation on Covid-19. | Over 460 instances of publishing “fake or provoking information" on the coronavirus pandemic online were found. | 1 |

| May 4 2020 | (BBC, 2020b) | News Article | Article informs Security of Service of Ukraine exposing disinformation about COVID-19 online. | "News pegs” were used “to create chaos and panic. Following instructions from their handlers, pro-Russian agents disseminated fake news about Easter celebrations, May holidays, quarantine and other measures connected with the rules of protection from the spread of the coronavirus infection.” | 1 |

| May 7, 2020 | (Kyriakidou, Morani, Soo, & Cushion, 2020) | Journal article | Study reviews tweets related to COVID-19 disease from major international news outlets. Findings summarize the discrepancies and disinformation between the truth. | Study highlights the urgency and the importance of fact-checking to combat disinformation campaigns. Holding news outlets and opinion leaders accountable for the facts and news which are spread based on their reporting is also crucial and important. | 1 |

| May 13, 2020 (Kevere, 2020) | (Kevere, 2020) | News Article | Article describes the Russian disinformation campaigns and its strategies used during the COVID-19 outbreak in Ukraine and surrounding areas. | Russian disinformation campaigns were targeted in Ukraine to present Russia and China as humanitarian leaders of the world plus as credible sources with trusted experts and troops to help. | 1, 2 |

| May 21 2020 | (Jozwiak, 2020a) | News article | Article follows up on a previous article regarding the monthly EU report on disinformation campaigns. Pro-Kremlin media outlets are still pushing disinformation and the article suggests that Iran is also joining China and Russia in dismantling western nations. | Article encourages EU countries and USA to go on the offensive and to fact check and combat disinformation from Pro-Kremlin media outlets. | 1 |

| May 22 2020 | (Ukraine Crisis Media Center, 2020a) | Review | Review examines the Kremlin’s history of disinformation campaigns and states that it can lead to multiple deaths. | “Disinformation can kill.” Russia is posturing its nation as less impacted by the virus by sowing discord through disinformation campaigns. | 1 |

| May 28 2020 | (Ukraine Crisis Media Center, 2020b) | Review | Russia continues to pump out fake numbers regarding cases and deaths due to COVID-19 disease. Rather than spread awareness to the issues dealing with the disease, small governments and Pro-Kremlin media outlets in Ukraine continue to pump out disinformation. | When faced with a choice between continuing to disinform the public to keep order or to give the hard truth about COVID-19 disease, Pro-Kremlin media outlets, Russian government officials, and small Ukrainian governments will choose the former. | 1, 2 |

Figure 2.

Timeline Diagram of Notable Misinformation and Disinformation incidents as relates to COVID-19 cases

From the selected materials in this review, the current information related to COVID-19 and healthcare was found to be aligned into two broad categories when discussing disinformation: 1) trust in and accuracy of COVID-19 messaging, and 2) access to COVID-19 related medical goods and services. Within both themes, disinformation presents unique challenges and concerns. Still, in both, the disinformation content discussed in the material revealed a malicious intent by primarily Russia and Russian-backed separatists (as previously seen prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in East Ukraine) (Jozwiak, 2020a; Tucker, 2020; Wilson and Starbird, 2020). Broadly, the malicious intent and execution of disinformation campaigns in Ukraine were intended to amplify and promote discord to create a political impact in Ukraine, particularly in the context of the ongoing war (Peel and Fleming, 2020; Sukhankin, 2020).

Disinformation addressing trust and accuracy of official messages

The first theme that emerged in our set of publications was how disinformation affected trust in authorities and the dissemination and reception of accurate health crisis messaging. Various papers discussed a spectrum of disinformation within this theme, from narratives that questioned the accuracy of official messaging to those that reinforced fake news in order to break trust with the government’s response. Overall, the majority of sources found in this review emphasized the importance of establishing trust in the official health advice, specifically regarding the coronavirus and specific ways the Ukrainian healthcare system is combating it (Freelon and Lokot, 2020; Peters, 2020).

European Union East StratCom offices found 80 coronavirus-related disinformation cases on popular media channels since January 2020 (Polityuk and Zinets, 2020; Wanat et al., 2020). Fake narratives and information about the pandemic varied, from the coronavirus being a human-made biological weapon tailored to Chinese DNA; to a pandemic spread by the United States (US) President and US soldiers; to the COVID-19 pandemic being entirely fake, as depicted in Russian media (Barnes et al., 2020; Emmott, 2020).

This “significant disinformation campaign” was reported in a European Union document that states the goal was to worsen the impact of the coronavirus, generate wide-spread panic, and cultivate distrust (Emmott, 2020). For example, disinformation campaigns have targeted vulnerable groups to obstruct measures to contain a COVID-19 outbreak, such as downplaying the case numbers and fatality statistics to convey a low risk of contagion (e.g., no need for physical distancing or face coverings) or disinforming the public that contagious individuals were arriving to a particular municipality, instigating panic and disruption (Arciga, 2020; Korybko, 2020; Melkozerova and Parafeniuk, 2020; Miller, 2020a, b; Peters, 2020).

These seemingly contradictory disinformation themes are examples of Russia’s multifaceted disinformation campaign against Ukraine. For instance, disinformation messaging in the occupied territories portrays Ukraine’s efforts to mitigate the pandemic as both inefficient and an overreaction by simultaneously 1) overstating the number of cases in the Ukrainian military (to make the Ukrainian forces look weak), and 2) criticizing Ukraine’s quarantine measures as excessive and damaging to business (Ukraine Crisis Media Center, 2020b). The portrayal of the Ukrainian government as weak and incompetent contributes to the public’s distrust of the state’s rules and regulations regarding preventive public health measures. Meanwhile, Russia continues to posture its officials as experts, well prepared and unified in the country’s attack against COVID-19 (Kevere, 2020; Shea, 2020; Ukraine Crisis Media Center, 2020a).

Disinformation prevents a truly unified response to combat the spread of disease. In occupied territories, for example, reports describe COVID-19 health measures as “softer and stricter [than those of the Ukrainian government],” with softer limitations such as keeping religious centers open, but stricter measures like criminalizing “fake news” and reducing benefits for senior citizens (Ukraine Crisis Media Center, 2020b).

Disinformation related to COVID-19 resources and support

In addition to focusing on disinformation that aimed to undermine trust in official COVID-19 crisis communication, the literature included in our review highlighted narratives that focused on pandemic resources and support, including comparisons to other countries. We found disinformation that interfered with access to legitimate COVID-19 resources and support as well as commentary about resources and support – both abroad and at home in Ukraine. These commentaries suggest an intention to influence political opinion, particularly in the conflict-affected areas.

The literature discussed examples of disinformation that could prevent the public from seeking effective medical goods or following sound medical advice. This disinformation included reports of “fraudsters” distributing medical products of “dubious quality” and disinformation campaigns promoting fake treatments that promised rapid cures for COVID-19 disease (BBC, 2020b; EUvsDisinfo, 2020)

In Ukraine and elsewhere, telecommunication service providers have responded to the pandemic by increasing free access to information resources and repurposing apps to serve the COVID-19 response (Lima, 2020). However, telecom services themselves have been the target of disinformation attacks, such as a conspiracy theory linking COVID-19 to 5G which led to the physical destruction of telephone masts in the UK (Lima, 2020). Likewise, our search found references to a disinformation campaign in Ukraine that led people to question the safety of their tap and drinking water, leading concerned residents to “overrun” the water agency’s phone lines and leading the agency to issue a clarifying statement (EURACTIV and Agence France-Presse, 2020a).

Disinformation instigated the physical interruption of access to healthcare, as well. Multiple documents in our review described an incident in Ukraine that involved a fake leaked email supposedly from the Ministry of Health (Arciga, 2020; EURACTIV and Agence France-Presse, 2020a; Korybko, 2020; Melkozerova and Parafeniuk, 2020; Miller, 2020a, b). The fake email, which falsely indicated there were five cases of COVID-19 in Ukraine, went viral on the same day that a plane of healthy evacuees from China’s Hubei province landed, sowing panic that incoming people might be bringing the first cases of the virus to Ukraine. This fear led residents in a small town to attack a bus carrying healthy evacuees from China to a medical center for quarantine. Protesters also fought with police and blocked the road to the medical facility. Residents in other towns similarly disrupted access to the local hospital out of fear that contagious people would intentionally be brought into their community (Miller, 2020b).

The literature described ways disinformation was used as political leverage against US sanctions (Jozwiak, 2020b, c). Russia, Iran, and China are carrying out coordinated attacks claiming the sanctions against Russia, Iran, Syria, and Venezuela are preventing these countries from carrying out an effective humanitarian and medical response (Jozwiak, 2020b, c). These narratives were found to serve the three countries’ desire to undermine trust in the West and pressure the US to lift sanctions. At the same time, placing the blame on the US could deflect criticism away from these aforementioned countries for their inability to provide adequate resources and supplies.

Similarly, a policy brief described the competition between the EU and Russia/China to be viewed as the “good guys” through health diplomacy (Kosmehl, 2020). Other documents refer to Ukraine’s need for outside assistance to fight the pandemic (Paul and Filipchuk, 2020) and the European Commission’s financial assistance issued to Ukraine (Ukraine Business Daily, 2020). On a more local level, the use of healthcare to “win hearts and minds” has a strong history in Eastern Ukraine throughout the ongoing conflict. To garner political support, pro-Russian separatists in the occupied territories and pro-Ukrainians under government control use health services to generate goodwill among people on both sides of the border and to create an image of life being better and safer on their side (Hyde, 2018).

Discussion

As seen in the included publications, disinformation about COVID-19 is pervasive in Ukraine, with multiple effects and suspected goals. The power and efficacy of disinformation campaigns can be inferred from the responsive actions taken by the Ukrainian government and smaller advocacy groups. In early 2020, a bill was considered in the Ukrainian parliament where purposeful spreading of disinformation could be fined and punished up to seven years in prison (EURACTIV and Agence France-Presse, 2020b). Since the outbreak of disinformation started worldwide, various small groups like StopFake and COVID-19MisInfo have created websites and databases to transparently monitor and counter misrepresented information, with a special focus on the COVID-19 pandemic (Haigh et al., 2018; Ryerson University Social Media Lab, 2020). In May 2020, the Ukrainian government identified over 300 individuals and over 2,100 internet communities online that were actively spreading fake and malicious information about the COVID-19 outbreak (BBC, 2020a).

Our review suggests that the disinformation related to crisis communication about COVID-19 was focused on eroding trust in the government’s response and the accuracy of the official health messaging or misleading the public with regard to accessing and receiving resources or support. Decreased trust in governments and public health systems leads to disregard for the official health advice and impacts the population’s medical decision-making, often with serious detrimental effects (Clark-Ginsberg and Petrun, 2020). These factors are compounded in disadvantaged or vulnerable populations, such as those living in poverty, regions of conflict or in areas with poor infrastructure. This can be attributed to a legacy of government mistreatment and a general lack of access to reliable information, which strengthens the impact of disinformation campaigns (Clark-Ginsberg and Petrun, 2020).

Media consumption and trust in media are slowly evolving in Ukraine. As of 2018, 82 percent of Ukrainian are online, an increase of 12 percent since 2015, and Ukrainians are increasingly turning to social media for news (Internews in Ukraine, 2018). According to a 2018 Internews study, Ukrainians strongly prefer national (as opposed to regional, global or Russian) media sources, with the exception of print media. Television was the more commonly used source for news, with internet usage varying by region and over time (Internews in Ukraine and USAID, 2018).

Importantly, the 2018 Internews study showed a steadily increasing use of Facebook for news – more commonly than other forms of social media. This trend implies that Ukrainians are turning to Facebook as a reliable source of news, with 42 percent of respondents in 2018 indicating a preference for Facebook for news over other forms of social media (Internews in Ukraine and USAID, 2018). Given the prominence of social media as a platform for disinformation campaigns, this trend could reveal an increasing exposure to disinformation among Ukrainians.

Based on the evidence, our recommendations are to 1) increase the transparency of health crisis communication, such as including eyewitness videos in television news communication; and, 2) address the leadership gap in disseminating reliable regional information about COVID-19 resources and support in Ukraine. As seen in many countries around the world, it is challenging to effectively reduce the community spread of the coronavirus when information is being maliciously skewed by a foreign country. Our study findings and recommendations seek to mitigate this problem.

By increasing transparency and including eyewitness videos, information providers earn more trust among the viewing audience. In a previous study examining the conflict in Ukraine in the TV news, analysts found that eyewitness videos affect perceptions of trustworthiness through “feelings of presence and empathy as well as perceptions of authenticity and bias” (Halfmann et al., 2019).

Establishing a legitimate and trusted entity at the regional level that possesses the capacity, capabilities and authority required to address the messaging related to COVID-19 resources and support would also inspire trust and confidence among local citizens. This entity would need to be directly supported by a transparently governed international partner, such as the United Nations, World Health Organization (WHO or NATO). An expert leadership committee could monitor and address hybrid tactics that are disinforming regional localities about COVID-19 resources and support. The WHO recently documented misinformation about COVID-19 research in its COVID-19 situational report 121, but only convened experts into a working group to help conduct scientific research on COVID-19, not to monitor disinformation challenges (WHO, 2020). Legitimate international and regional expert committees that can act as credible and powerful watchdog organizations and disseminate verified information are essential to countering fake news. More recently, a new initiative by the United Nations has started to verify COVID-19 messaging (United Nations, 2020a, b). Only time will tell if this initiative will be adopted locally in Ukraine and in other countries around the world.

These efforts must be tailored to specific populations according to their vulnerability to disinformation, their media preferences, and their access to quality resources and medical care. Coordination with non-governmental entities, such as faith-based organizations, community organizations and NGOs, may prove effective in areas where these entities have the trust of the local population (Clark-Ginsberg and Petrun, 2020).

Our review has several possible limitations. When identifying publications for review, confirmation bias may have occurred in selection process. To reduce this possible bias, we had two researchers independently choose the accepted papers and established an explicit set of inclusion criteria to use. The reliability of the thematic analysis of this review could be a possible limitation, despite having two researchers performing it. A third impartial researcher was used to check on the reliability of themes assigned to the included papers and broke any tie between the two authors. Additionally, it is quite unlikely that we identified every relevant published article in the literature due to only selecting English articles and not using any specialized Ukrainian search engine, and due to the high amount of rapid publications with COVID-19 research which may even produce low quality publication due to research fatigue (Patel et al., 2020b). It would be beneficial to work with Ukrainian researchers to conduct a similar study in the Ukrainian and Russian languages, taking into consideration the reputability of the media sources. The misinformation or disinformation terminology of the included papers in this review may not accurately align with the DoD mandate of definitions. Thus, there may be cases where original authors wrote “disinformation” but might be discussing instances of misinformation, and vice versa. Similarly, our use of “disinformation” throughout this paper may be implying an intentional campaign in cases where the erroneous information was simply misinformation, such as an honest misinterpretation of medical advice that then went viral.

Nevertheless, this review sheds light on opportunities for further research and scientific inquiry. Further research methodologies and evidence should be established to improve COVID-19 knowledge, resources, and support for vulnerable populations in Ukraine. This recommendation is particularly important if there are subsequent surges of this novel coronavirus or other emerging infections regionally and globally. An analysis of disinformation by platform would lend insight into which channels are the most infiltrated and could be compared with data on Ukrainians’ use of media and trust in specific types of media. Similarly, cases wherein the disinformation was spread by mainstream media deserve more attention to fully grasp how frequently, for what reason, and how this occurred.

Analysis of communication and trust at the institutional level – including non-governmental entities – could also improve strategies to effectively respond to the pandemic: Which organizations do Ukrainians trust most for health-related information and care? How are these organizations communicating, and are they being usurped by disinformation? Could these selected organizations help to counter the negative impact of disinformation that destroys trust? As noted above, these analyses will be most useful when they assess data by community (e.g., rural versus city, Russian-speaking versus Ukrainian-speaking, and conflict versus conflict-free zones).

Further research is needed to assess the efficacy of disinformation campaigns and their overall impact. Additional contextual information such as data on Ukraine’s COVID-19 cases and deaths, an analysis of the strength of the state’s response, as well as measures of civilian adherence to official guidelines could deepen our understanding of how these campaigns work and how severe is the threat they pose. While it may be difficult to obtain, evidence of Russia’s (and other states’) government involvement in disinformation campaigns provides insights for international relations, while uncovering the mode of operation for developing and disseminating the disinformation is also an important piece to the complex overall puzzle.

Additional insight into Ukrainians’ media literacy and awareness of resources to fact check potential disinformation could help formulate more specific educational approaches. For example, the 2018 Internews study found that the number of Ukrainians who critically evaluate news sources for accuracy has steadily (but marginally) increased since 2015. Nonetheless, under 30 percent said they pay attention to the source of the news and whether more than one point of view is presented, and only 14 percent said they pay attention to the owner of the media. At the same time, 26 percent said they trust media intuitively (Internews in Ukraine, & USAID, 2018). An updated survey of media literacy in the context of COVID-19 and a study of the use and efficacy of verification sources like StopFake would both complement our review of disinformation literature.

Conclusion

The news and media events that occurred in Ukraine are an early indicator of disinformation during the COVID-19 outbreak. This research paper provides an overview of how the disinformation of the health crisis from a calculating outside force impacted communities in Ukraine. This impact makes Ukraine a valuable case-study on Health Crisis Communication during a global pandemic. What makes this particularly intriguing are the numerous examples of disinformation and their negative implications, both regionally and nationally in this vulnerable and conflict-ridden region.

Acknowledgments

Funding

TBE was country lead for NATO Science for Peace and Security Programme fund numbers: G5432 & G5663, which supported activities of Advanced Research Workshop and Advanced Training Course in Ukraine. SSP was supported by the Fogarty International Center and National Institute of Mental Health, of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43 TW010543. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, NATO Science for Peace and Security Programme, or any institution.

References

- Arciga J (2020, February 20). Coronavirus Disinformation Sparked Violent Protests in Ukraine. Daily Beast. Retrieved from https://www.thedailybeast.com/coronavirus-disinformation-sparked-violent-protests-in-ukraine

- Barnes JE, Rosenberg M, & Wong E (2020, March 28). As Virus Spreads, China and Russia See Openings for Disinformation. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/28/us/politics/china-russia-coronavirus-disinformation.html

- BBC. (2020a, May4). Covid-19 disinformation: Ukraine busts 301 online. BBC News. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/2397471781?accountid=11311 [Google Scholar]

- BBC. (2020b, April2). Ukraine opens 30 criminal cases over covid-19 disinformation. BBC News. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/2385109273?accountid=11311 [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Broniatowski DA, Jamison AM, Qi S, AlKulaib L, Chen T, Benton A, et al. (2018). Weaponized Health Communication: Twitter Bots and Russian Trolls Amplify the Vaccine Debate. American journal of public health, 108(10), 1378–1384. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2020). Health Communication Basics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/healthbasics/whatishc.html [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Ginsberg A, & Petrun EL (2020). Communication missteps during COVID-19 hurt those already most at risk. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. [Google Scholar]

- Emmott R (2020, March 18). Russia deploying coronavirus disinformation to sow panic in West, EU document says. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-disinformation/russia-deploying-coronavirus-disinformation-to-sow-panic-in-west-eu-document-says-idUSKBN21518F

- EURACTIV, & Agence France-Presse. (2020a, March27). Ukraine struggles to debunk fake virus news. EURACTIV. Retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/ukraine-struggles-to-debunk-fake-virus-news/

- EURACTIV, & Agence France-Presse. (2020b, February5). OSCE warns Ukraine over disinformation bill. EURACTIV. Retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-ea/news/osce-warns-ukraine-over-disinformation-bill/

- EUvsDisinfo. (2020, March26). Disinformation Can Kill. EUvsDisinfo. Retrieved from https://euvsdisinfo.eu/disinformation-can-kill/ [Google Scholar]

- Francis D (2018, May 9). Unreality TV: Why the Kremlin’s Lies Stick. Atlantic Council. Retrieved from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/unreality-tv-why-the-kremlin-s-lies-stick-at-home.

- Freelon D, & Lokot T (2020). Russian Twitter disinformation campaigns reach across the American political spectrum. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1(1). [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielle L (2020, May 8). Global Engagement Center Update on PRC Efforts to Push Disinformation and Propaganda around COVID. US Department of State. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/briefing-with-special-envoy-lea-gabrielle-global-engagement-center-update-on-prc-efforts-to-push-disinformation-and-propaganda-around-covid/

- Haigh M, Haigh T, & Kozak NI (2018). Stopping Fake News: The work practices of peer-to-peer counter propaganda. Journalism Studies, 19(14), 2062–2087. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1316681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann A, Dech H, Riemann J, Schlenker L, & Wessler H (2019). Moving Closer to the Action: How Viewers’ Experiences of Eyewitness Videos in TV News Influence the Trustworthiness of the Reports. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 96(2), 367–384. doi: 10.1177/1077699018785890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harding L (2018, May 3). ‘Deny, distract and blame’: how Russia fights propaganda war. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/may/03/russia-propaganda-war-skripal-poisoning-embassy-london.

- HHS Cybersecurity Program. (2020). COVID-19 Related Nation-State and Cyver Criminal Targeting of the Healthcare Sector (Report# 202005141030). Retrieved from https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/hc3-tlp-white-covid19-related-nation-state-cyber-criminal-targeting-healthcare-sector-5-14-2020.pdf

- Hyde L (2018, August 21). Now Healthcare Is a Weapon in Ukraine’s War. Coda. Retrieved from https://www.codastory.com/disinformation/armed-conflict/healthcare-weapon-ukraine/

- Internews in Ukraine. (2018). Trust in Media on the Rise in Ukraine – a New USAID-Internews Media Consumption Survey Says. Retrieved from https://internews.in.ua/news/trust-in-media-on-the-rise-in-ukraine-a-new-usaid-internews-media-consumption-survey-says/

- Internews in Ukraine, & USAID. (2018). Media Consumption Survey in Ukraine 2018. Retrieved from https://internews.in.ua/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2018-MediaConsumSurvey_eng_FIN.pdf

- Jack C (2017). Lexicon of Lies: Terms for Problematic Information. Data & Society. Retrieved from: https://datasociety.net/pubs/oh/DataAndSociety_LexiconofLies.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jankowicz N (2019, April 17). Ukraine’s Election Is an All-Out Disinformation Battle. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/04/russia-disinformation-ukraine-election/587179/

- Jozwiak R (2020a, March 18). EU Monitors Say Pro-Kremlin Media Spread Coronavirus Disinformation. RadioFreeEurope RadioLiberty. Retrieved from https://www.rferl.org/a/eu-monitors-say-pro-kremlin-media-spread-coronavirusdis-information/30495695.html

- Jozwiak R (2020b, May 21). EU Monitor Sees Drop In COVID-19 Disinformation, Urges Social Media To Take More Action. RadioFreeEurope RadioLiberty. Retrieved from https://www.rferl.org/a/covid-19-disinformation-eu-decrease-kremlin-china-bill-5g-gates/30625483.html

- Jozwiak R (2020c, April 22). EU Monitors See Coordinated COVID-19 Disinformation Effort By Iran, Russia, China. RadioFreeEurope RadioLiberty. Retrieved from https://www.rferl.org/a/eu-monitors-sees-coordinated-covid-19-disinformation-effort-by-iran-russia-china/30570938.html

- Kevere O (2020, May 13). The Illusion of Control: Russia’s media ecosystem and COVID-19 propaganda narratives. Visegrad Insight. Retrieved from https://visegradinsight.eu/the-illusion-of-control-russian-propaganda-covid19/ [Google Scholar]

- Korybko A (2020, February 22). Ukraine’s anti-COVID-19 riot is due to fake news and media-driven fear. CGTN. Retrieved from https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-02-22/Ukraine-s-anti-COVID-19-riot-is-due-to-fake-news-and-media-driven-fear-Oi9eszIfzW/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Kosmehl M (2020). Geopolitical symptoms of COVID-19: Narrative battles within the Eastern Partnership. Bertelsmann/Stiftung Policy Brief| 08.04. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lima JM (2020, April 20). Live / Covid-19 news: How the telecoms world is dealing with the pandemic. Capacity Magazine. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/2400244451?accountid=11311 [Google Scholar]

- Melkozerova V, & Parafeniuk O (2020, March 3). How coronavirus disinformation caused chaos in a small Ukrainian town. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/how-coronavirus-disinformation-caused-chaos-small-ukrainian-town-n1146936

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Disinformation. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/disinformation

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Misinformation. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/misinformation

- Miller C (2020a, March 9). A Small Town Was Torn Apart By Coronavirus Rumors. BuzzFeed News Retrieved from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/christopherm51/coronavirus-riots-social-media-ukraine

- Miller C (2020b, February 20). A Viral Email About Coronavirus Had People Smashing Buses And Blocking Hospitals. BuzzFeed News Retrieved from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/christopherm51/coronavirus-ukraine-china

- Mosquera ABM, & Bachmann SD (2016). Lawfare in hybrid wars: the 21st century warfare. Journal of International Humanitarian Legal Studies, 7(1), 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- NATO. (2017, September). NATO Strategic Communication (StratCom) Handbook. Retrieved from http://stratcom.nuou.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/NATO-STRATEGIC-COMMUNICATION-HANDBOOK.pdf [Google Scholar]

- NATO. (2019). NATO’s response to hybrid threats. Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_156338.htm

- Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. (2020, January). DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States. Retrieved from https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/dictionary.pdf

- Patel SS, Grace RM, Chellew P, Prodanchuk M, Romaniuk O, Skrebets Y, et al. (2020a). “Emerging Technologies and Medical Countermeasures to Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) Agents in East Ukraine”. Conflict and Health, 14(1), 24. doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00279-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SS, Rogers MB, Amlôt R, & Rubin GJ (2017). What do we mean by’community resilience’? A systematic literature review of how it is defined in the literature. PLoS currents, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SS, Webster RK, Greenberg N, Weston D, & Brooks SK (2020b). Research fatigue in COVID-19 pandemic and post-disaster research: causes, consequences and recommendations. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). doi: 10.1108/DPM-05-2020-0164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A, & Filipchuk V (2020, March 31). The impact of COVID-19 on the EU’s neighbourhood: Ukraine. European Policy Centre. Retrieved from http://www.epc.eu/en/Publications/The-impact-of-COVID-19-on-the-EUs-neighbourhood-Ukraine~31202c

- Peel M, & Fleming S (2020, March 17). EU warns of pro-Kremlin disinformation campaign on coronavirus. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/d65736da-684e-11ea-800d-da70cff6e4d3

- Peters J (2020, February 21). Coronavirus email hoax led to violent protests in Ukraine. The Verge. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2020/2/21/21147969/coronavirus-misinformation-protests-ukraine-evacuees

- Polityuk P, & Zinets N (2020, February 21). After clashes, Ukraine blames disinformation campaign for spreading coronavirus panic. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/china-health-ukraine/after-clashes-ukraine-blames-disinformation-campaign-for-spreading-coronavirus-panic-idINL8N2AL335

- Pomerantsev P, & Weiss M (2014). The menace of unreality: How the Kremlin weaponizes information, culture and money. New York: Institute of Modern Russia. [Google Scholar]

- Popovych N, Makukhin O, Tsybulska L, & Kavatsiuk R (2018). Image of European countries on Russian TV. Retrieved from https://uacrisis.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/TV-3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P (2018). Crisis Communication in Public Health Emergencies: The Limits of ‘Legal Control’ and the Risks for Harmful Outcomes in a Digital Age. Life sciences, society and policy, 14(1), 4–4. doi: 10.1186/s40504-018-0067-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryerson University Social Media Lab. (2020). About the COVID19MisInfo.org Portal. Retrieved from https://covid19misinfo.org/

- Samet JM, & Patel SS (2011). The psychological and welfare consequences of the Chernobyl disaster: a systematic literature review, focus group findings, and future directions. Retrieved from USC Institute for Global Health: https://uscglobalhealth.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/chernobyl_report_april2011.pdf

- Samet JM, & Patel SS (2013). Selected Health Consequences of the Chernobyl Disaster: A Further Systematic Literature Review, Focus Group Findings, and Future Directions. Retrieved from USC Institute for Global Health: https://uscglobalhealth.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/samet-patel-chernobyl-health-report-2013-light-1.pdf

- Shea J (2020, April 21). Expert on Eastern Europe healthcare voices concern about COVID-19 in Russia and Ukraine. Medical Express. Retrieved from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-04-expert-eastern-europe-healthcare-voices.html [Google Scholar]

- Starbird K, & Wilson T (2020). Cross-Platform Disinformation Campaigns: Lessons Learned and Next Steps, The Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, Volume 1, Issue 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhankin S (2020). COVID-19 As a Tool of Information Confrontation: Russia’s Approach. The School of Public Policy Publications, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Talant B (2020, March 18). Coronavirus misinformation goes viral in Ukraine. Kyiv Post. Retrieved from https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/coronavirus-misinformation-goes-viral-in-ukraine.html.

- Tucker P (2020, March 26). Russia Pushing Coronavirus Lies As Part of Anti-NATO Influence Ops in Europe. Defense One. Retrieved from https://www.defenseone.com/technology/2020/03/russia-pushing-coronavirus-lies-part-anti-nato-influence-ops-europe/164140/

- Ukraine Business Daily. (2020, April8). EU To Issue Eur190 Mln To Ukraine To Fight Coronavirus. Ukraine Business Daily. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/2387424188?accountid=11311 [Google Scholar]

- Ukraine Crisis Media Center. (2020a, May28). How Kremlin (mis)handles COVID-19 at home and abroad. Ukraine Crisis Media Center. Retrieved from https://uacrisis.org/en/how-kremlin-mis-handles-covid-19-at-home-and-abroad [Google Scholar]

- Ukraine Crisis Media Center. (2020b, May22). COVID-404. Implications of COVID-19 in the occupied territories of Ukraine. Ukraine Crisis Media Center. Retrieved from https://uacrisis.org/en/implications-of-covid-19-in-the-occupied-territories-of-ukraine [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2020a). UN launches new initiative to fight COVID-19 misinformation through ‘digital first responders’. UN News. Retrieved from https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/05/1064622 [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2020b). Verified. Retrieved from https://www.shareverified.com/en

- Wanat Z, Cerulus L, & Scott M (2020, March 19). EU warns of ‘pro-Kremlin’ disinfo on coronavirus pandemic. Politico. Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-warns-on-pro-kremlin-disinfo-on-coronavirus-pandemic/

- WHO. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 121. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200520-covid-19-sitrep-121.pdf?sfvrsn=c4be2ec6_4 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T, & Starbird K (2020). Cross-platform disinformation campaigns: lessons learned and next steps. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1(1). [Google Scholar]