ABSTRACT

Introduction

Understanding the pathogenesis and risk factors to control the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is necessary. Due to the importance of the inflammatory pathways in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 patients, evaluating the effects of anti-inflammatory medications is important. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) is awell-known glucose-lowering agent with anti-inflammatory effects.

Areas covered

Resources were extracted from the PubMed database, using keywords such as glucagon-like peptide-1, GLP-1 RA, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, inflammation, in April2021. In this review, the effects of GLP-1RA in reducing inflammation and modifying risk factors of COVID-19 severe complications are discussed. However, GLP-1 is degraded by DPP-4 with aplasma half-life of about 2–5 minutes, which makes it difficult to measure GLP-1 plasma level in clinical settings.

Expert opinion

Since no definitive treatment is available for COVID-19 so far, determining promising targets to design and/or repurpose effective medications is necessary.

KEYWORDS: Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, glp-1, covid-19, pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory

1. Introduction

Since December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has emerged as a novel respiratory infection disease in Wuhan, China [1]. The infection has spread drastically that infected more than about 200 million people worldwide, leading to more than 4 deaths so far (August 1st, 2021) [2]. Considering the contagious characteristic of COVID-19, besides lack of a proper treatment for infected patients, COVID-19 pandemic has already imparted a huge burden on patients, families, healthcare system, and societies. As a result, scientists have put great efforts to find proper biomarkers for the detection of susceptible patients in severe forms of the infection. So, the early diagnosis will be facilitated before the onset of severity, which could lead to a reduction in the rate of mortality and serious complications. Moreover, considering several unknown features of this infection, different late-onset and long-term complications might be plausible. Hence, it is beneficial to understand the comorbidities and risk factors associated with the increased risk of severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19.

One of the most important risk factors in association with severe COVID-19 infection is diabetes mellitus (DM) since the mortality rate of diabetic patients is almost three times higher than the normal population [3,4]. Therefore, investigating COVID-19 infection in the context of DM could help in better the understanding of possible mechanisms responsible for the progression of COVID-19 infection to severe life-threatening diseases. On the other hand, the fact that millions of people live with DM worldwide [5] highlights the importance of understanding pathophysiological pathways and risk factors related to the development of the diseases to severe conditions with undesirable outcome.

The mechanisms involved in controlling the blood glucose level have been suggested to affect the disease outcome in patients with COVID-19 [6]. In addition, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor that has an established role in the virus entry into host cells are a well-documented pathway responsible for macro and microvascular complications in diabetic patients [5,7–9]. On the other hand, incretin hormones, which are components of endogenous blood glucose control pathways, have demonstrated anti-inflammatory functions as well, which make them potential factors in determining the chance of developing severe COVID-19 infection. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a type of incretin hormone that is produced and released from intestinal cells. Different systems in the body, including the central nervous system, respiratory system, and cardiovascular system, express GLP-1 receptors [10]. One of the well-known functions of GLP-1, which has led to the application of GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) as a medication for controlling the glucose homeostasis in diabetic patients, is the stimulation of insulin secretion besides the inhibition of glucagon production [11]. Indeed, in diabetic patients due to the altered secretion of GLP-1, the anti-inflammatory mechanism does not function properly. Hence, this dysfunction alongside the hyperglycemia could be considered as a predisposing factor to a more severe form of SARS-CoV-2 infection in diabetic patients [12].

In this article, the common inflammatory pathways associated with COVID-19 pathophysiology and GLP-1 functions have been discussed, in order to outline the anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1 in different systems of the body and evaluate its potential applications in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COVID-19. In addition, given the importance of prevention and control of severe complications of COVID-19 as well as the reduction of mortality in high-risk patients, potential effects of GLP-1 in controlling the inflammatory status in metabolic diseases with the aim of controlling the risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 severe complications have been reviewed.

2. Search strategy

The resources were extracted from the PubMed database, in April 2021, using the keywords of (‘GLP-1’ OR ‘Glucagon-like peptide-1’ OR ‘GLP-1RA’) AND (‘SARS-CoV-2’ OR ‘COVID-19’ OR ‘novel coronavirus’) AND (‘inflammation’ OR ‘anti-inflammatory’ OR ‘cytokine storm’); the articles’ abstracts were initially assessed in order to determine whether they are relevant to the title of article. A reference list of the related articles has also been evaluated and included in this paper, in case of proper relevancy. The full texts of all relevant articles were evaluated and the findings were interpreted by the authors to obtain the necessary information for writing the manuscript.

3. The common pathway of ACE2 receptor, diabetes mellitus (DM), and SARS-CoV-2

There is a mutual relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and DM. Diabetes mellitus is an important risk factor in determining COVID-19 prognosis, while the new onset of DM in patients with COVID-19 has been reported as well. The exact underlying mechanism is still unknown; however, several factors have been suggested in this regard [13]. One of the most probable responsible mechanisms for the exacerbation and development of DM in COVID-19 patients is attributed to the expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor in insulin-producing cells. ACE2 is known as an important receptor for virus entry into host cells. This enzyme is widely expressed in cells of various organs of the body, including beta cells of the pancreas, brain, and liver, and have the highest level of expression in the epithelial cells of the intestine and lungs. As a result, various organs’ cells could be infected by SARS-CoV-2 [14,15].

However, the imbalance in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and ACE/ACE2 proportion in patients with DM puts them at greater risk for developing SARS-CoV-2 complications. In addition, the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) enzyme, which breaks down GLP-1 after secretion in the body, has been suggested as an effective factor in SARS-CoV-2 entry into human cells. Indeed, the plasma activity of this enzyme is higher in diabetic patients [16–18]. This implies that diabetic individuals are at higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Meanwhile, pancreatic cells have cellular receptors for the virus; hence, the virus induces functional disturbances among infected pancreatic beta cells, which lead to the development of the symptom of new-onset DM [19]. Thus, investigating cellular damage mechanisms in the pathophysiology of COVID-19 and the determining factors that play protective roles in tissue function and structure are of high value.

4. GLP-1, SARS-CoV-2, and pancreatic cells

4.1. SARS-CoV-2 and pancreatic cells injury

Through the cellular injury induced by SARS-CoV-2, the activation of inflammasomes results in the conversion of pro-inflammatory cytokines to inflammatory cytokines. IL-1β and TNF-α are activated due to caspase-8 and caspase-1 activity, which causes cellular damage and apoptosis by NF-κB pathway. In addition, NF-κB activation increases the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which results in cellular damage. Studies have shown elevated plasma levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in patients with COVID-19 [20–23].

The anti-apoptotic effects of GLP-1RA on pancreatic cells are conducted through different intracellular signaling pathways. In the first pathway, GLP-1RA inhibits the apoptotic mechanisms through activating phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K), protein kinase Cζ (PKCζ), and protein kinase B (PKB), which finally leads to the inhibition of NF-κB pathway and caspase activation. The other anti-apoptotic mechanism of GLP-1RA intracellular signaling is based on Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL activation. Accordingly, GLP-1RA induces adenylyl cyclase activity that leads to an increase in cAMP, which in turn, Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL are activated through PKA and CREB activation [24]. On the other hand, previous studies showed that IL-1β and TNF-α have an important role in the development and exacerbation of DM by damaging beta cells of the pancreas, which are responsible for secreting insulin hormone in the body [25,26]. Therefore, the presence of common components (IL-1β and TNF-α) in both of the above-mentioned pathways demonstrates possible association of cellular damage mechanisms in DM and COVID-19.

4.2. GLP-1 and pancreatic cells (glucose hemostasis, cellular apoptosis, and inflammation)

The anti-inflammatory roles of GLP-1 in DM have been investigated through animal studies, which shows that regardless of GLP-1 effects on glycemic control and weight loss, it reduces the pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β [27]. In a study performed on a rat model to evaluate the anti-apoptotic effects of GLP-1 on pancreatic beta cells, it was shown that in the simultaneous control of blood sugar and insulin levels, the absence of GLP-1 increased the pancreatic cell death. Indeed, the presence of GLP-1 decreased the rate of cellular death by reducing the cytokine-induced apoptosis, which is mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β [28].

Moreover, a study on pancreatic cells isolated from human samples showed that GLP-1, in addition to its effects in controlling blood sugar and increasing the pancreatic mass, reduces apoptosis in pancreatic cells, including beta cells by downregulating caspase-3 pathway and increasing the activity of anti-apoptotic factors such as Bcl-2 [29]. Therefore, it is proposed that GLP-1RA have direct impacts on insulin-producing cells and potential anti-inflammatory roles, besides the ability to control glucose hemostasis.

5. GLP-1, SARS-CoV-2, and cardiovascular disease

5.1. SARS-CoV-2 and cardiovascular injury

Another important considerationin particular, among patients with DM during the COVID-19 pandemic, is to control other metabolic factors and probable comorbidities in addition to blood sugar level. Besides DM, cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension are important comorbidities that are potentially involved in determining the severity of the infection, disease outcomes, and prognosis [30].

It is noteworthy that cardiovascular injuries due to SARS-CoV-2 are also observed in infected patients, which potentially increase the mortality rate. Suggested responsible mechanisms for cardiovascular injuries include increased inflammatory responses of T cells, increased secretion of inflammatory cytokines, rupture of preexisting atherosclerotic plaques, and fibrous tissue formation [31,32]. Results of an autopsy study in patients who died of COVID-19 indicated that although PCR test was positive only in 35% of the cases, inflammatory changes, and macrophage infiltration were observed in the cardiac tissue of 86% of the cases. It has been hypothesized that the role of the underlying inflammation and immune cells infiltration in inducing cellular damage within the affected tissue is more significant than the presence of viral particles [33]. Furthermore, endothelial damage contributes to cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 due to ROS production induced by inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α in particular. This mechanism is mediated by the NADPH and NF-κB pathway [34].

5.2. GLP-1 and cardiovascular system (antioxidant mechanisms, chronic inflammation, and blood pressure)

Studies on the expression of GLP-1 in the cardiovascular system showed that the GLP-1 receptor is expressed in the cardiac tissue, with the same structure as found in pancreatic cells [35]. Further studies on the function of GLP-1 in the cardiovascular system have shown that GLP-1 potentially affects cardiac function in different aspects. For instance, GLP-1 reduces blood pressure by lowering the secretion of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) [36]. In addition, the protective effects of GLP-1 against oxidants through increasing the production of endogenous antioxidants can protect cardiomyocytes against cellular apoptosis [37].

In order to evaluate the antioxidant effects of GLP-1 in vascular endothelial cells, especially with regard to the induction of inflammation and initiation of oxidative reactions, caused by TNF-α, it has been shown that GLP-1 increased the production of antioxidant agents by inhibiting NF-κB and PKC-α and NADPH oxidase pathways [38]. It has also been reported that circulating levels of GLP-1 were correlated with coronary artery atherosclerosis. However, atherosclerosis, as a chronic disease, could be considered as an important comorbidity in COVID-19 patients [39,40]. Studies on GLP-1 have demonstrated its protective effects against cardiomyocytes apoptosis due to inflammation and highlighted its potential role in alleviating previous chronic inflammation due to preexisting atherosclerotic plaques, both of which are considered as SARS-CoV-2 risk factors. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the function of GLP-1 in cardiovascular comorbidity, especially in the era of COVID-19 pandemic.

6. GLP-1, SARS-CoV-2, and the gut microbiota

6.1. SARS-CoV-2 infection and intestinal microbiota disturbance

Regarding the effects of the intestinal microbiome on disease severity among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, it has been reported that disturbance of the intestinal microbiome balance could aggravate the patients’ status by enhancing the inflammatory responses in the body [41]. Furthermore, examining the fecal samples of hospitalized COVID-19 patients showed that dysbiosis remained in patients even after the improvement of respiratory and systemic symptoms. However, this imbalance in the intestinal microbiome can be associated with an increased severity of the disease in COVID-19 patients [42]. One of the responsible mechanisms could be the alteration in the microbiota with the contribution of defensive bacteria including Klebsiella, Streptococcus spp., and Ruminococcus gnavus that are associated with over-secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and exacerbation of the cytokine storm in infected patients [43].

6.2. GLP-1 and gut microbiota (receptor expression, secretion, and inflammatory mechanisms)

However, the fermentative elements produced as a result of gut microbiota functioning could be considered as a GLP-1 secretion stimulant. Moreover, the effect of intestinal microbiota on the growth of intestinal L-cells, which produce GLP-1, has been observed in animal studies [44].

Additionally, due to the imbalance in the gastrointestinal microbiome, the expression of GLP-1 receptors decreases; indeed, the reduction of these receptors impairs the function of GLP-1 through the gut-brain-periphery axis [45]. Hence, a bidirectional association between GLP-1 secretion and the gut microbiota could be considered. It implies that not only the gut microbiota status could affect the GLP-1 secretion, but also GLP-1 could be considered as an effector in gut microbiota function by different mechanisms such as increasing the intestinal motility and decreasing the appetite. In addition, GLP-1 could be effective in modulating inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB, which is induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [46].

7. GLP-1, SARS-CoV-2, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

7.1. SARS-CoV-2 infection and NAFLD

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) that has an overall prevalence of about 25% could be considered a worldwide concern. Moreover, the prevalence of NAFLD is higher among individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (with a prevalence of about 55%). In recent decades, the incidence of NAFLD in most of the world’s populations has been increased [47,48].

It has been observed that NAFLD is associated with more severe symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection. This could be attributed to the chronic inflammation associated with NAFLD. Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 infection, as an acute inflammatory event, could exacerbate the patients’ outcome [49]. In addition, NAFLD is usually associated with other metabolic diseases including obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome that could potentially affect the severity of COVID-19 infection. However, different reports indicate that even with the elimination of confounding factors, the presence of NAFLD in COVID-19 patients is associated with a higher risk of developing severe complications of the disease [50].

7.2. GLP-1 and NAFLD (progression, inflammatory mechanisms, and weight loss)

Results of clinical trials showed that GLP-1RA can be effective in reducing liver steatosis, decreasing liver enzymes’ levels, reversing the fibrosis process, and enhancing the sensitivity of the liver to insulin. Meanwhile, since the main treatment of NAFLD is lifestyle modification and weight loss, GLP-1 could be beneficial to control the disease by satiety induction and thus reducing the food intake [51,52]. In addition, results of evaluating the effectiveness of anti-diabetic medications in the improvement of NAFLD showed GLP-1RA significantly reduced liver steatosis in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients, in comparison with other anti-diabetic medications [53,54].

On the other hand, the level of C-reactive protein (CRP), which is known as an indicator of inflammation rises in patients with NAFLD, therefore creates an underlying inflammation in these patients. Besides, it has been observed that an increase in CRP levels is significantly associated with the development of NAFLD [55–57]. However, studies conducted aiming to determine the anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1 have shown that the administration of GLP-1RA significantly reduces CRP levels [58]. Therefore, GLP-1 might be effective in reducing chronic inflammation among this population and help to improve the lifestyle by appetite reduction and ultimately reducing risk of developing complications in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

8. GLP-1, SARS-CoV-2, and adipose tissue

8.1. SARS-CoV-2 infection and obesity

Studies have been shown that due to the various factors, especially chronic inflammation and impairment of the immune system among obese individuals, they have a higher risk of developing severe SARS-CoV-2 infection [59,60]. In addition to the overexpression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α in the adipose tissue, an increase in DPP-4 enzyme and a decrease in the GLP-1 level has been observed in obese diabetic individuals with insulin resistance [61,62]. Given the significant role of inflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of COVID-19 infection, it is important to consider the evaluation of adipose tissue volume and obesity to control the underlying inflammation and metabolic disorders with the aim of reducing the risk of severe COVID-19 complications.

8.2. GLP-1 and adipose tissue (inflammatory mechanisms and weight loss)

GLP-1RA affects adipose tissue in different ways, including weight loss by reducing appetite through the gut-brain axis [63]. In the short term, GLP-1RA reduces visceral fat by affecting dietary behaviors and appetite. Significant weight loss has also been reported among obese patients with T2DM in the long-term [64,65]. In addition to the effects of GLP-1 and its agonists on weight loss and visceral fat reduction, animal studies have shown that lipogenic mRNA expression decreased in mice treated with GLP-1RA. It was also observed that the expression of mRNA associated with markers of macrophage type 1, which is associated with inflammation, have been decreased in the obese mouse model of DM [66]. It should be noted that besides the therapeutic effects of GLP-1RA in obese patients, a study on the relationship between circulating GLP-1 levels as an indicator of metabolic syndrome showed that measurement of circulating GLP-1 could be considered as an early diagnostic marker of metabolic syndrome, especially obesity [67].

9. GLP-1, SARS-CoV-2, and lung tissue

9.1. SARS-CoV-2 and respiratory cells injury

One of the most important complications developed in patients who are infected by SAR-CoV-2 is the incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is associated with a high mortality rate among patients. In this context, as a result of increased vascular permeability, the surfactant secreted by type 2 pneumocytes becomes dysfunctional and as a result, the alveoli collapse and the instability in the lung tissue leads to pulmonary dysfunction [68–70].

Examination of lung autopsy specimens in patients who developed ARDS demonstrated the role of the immune system and inflammatory pathways in the occurrence and progression of ARDS. The significant presence of CD4 + T cells and inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ indicated the crucial role of inflammation in this process [71,72]. In addition, animal studies aimed at investigating the role of inflammatory pathways in the development of ARDS and acute lung injury (ALI) due to respiratory viral infections, such as influenza virus, highlighted the role of increased activity of inflammatory pathways of the host’s immune system in disease severity and cellular damages [73].

One of the proposed SARS-CoV-2 cellular injury patterns is necroptosis, which is mediated through the receptor-interacting protein kinase-3 (RIPK3) phosphorylation. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 induces the caspase-8 activity, leading to maturation of pro-IL-1β into IL-1β. IL-1β, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, induces cellular injury through necroptosis. Besides, caspase-8 induces the caspase-3 activity, which causes cellular apoptosis. As a result, both patterns could be responsible for respiratory cell injuries [74].

9.2. GLP-1 and lung injury (cytokine storm, surfactant production, and long term fibrosis formation)

A study on a mouse model to evaluate the effect of GLP-1 analogs on ALI and ARDS caused by influenza virus showed that GLP-1 analogs do not affect viral particles, but could reduce the mortality rate among infected mice by inhibiting inflammatory pathways and cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [75]. One of the key factors to sustain the function of the lung is surfactant. Surfactant is a substance that is mainly composed of phosphatidylcholine, which is a type of phospholipid and is secreted from type 2 pneumocytes. The incidence of ARDS in premature infants whose surfactant production has not been properly established demonstrates the importance of this substance in human respiratory function [76,77]. Moreover, a decrease in surfactant production in adults have been reported as a result of cellular lung damage due to different factors, including viral infections such as SARS-CoV-2 [78].

In addition to its important role in reducing the surface tension that prevents alveolar collapse during exhalation, surfactant plays an important role in inflammatory pathways and protects pneumocytes against inflammatory cytokines [79]. In clinical studies, the level of surfactant has been evaluated as an important factor in determining the outcome and mortality rate among patients, who developed ALI and ARDS induced by SARS-CoV-2. Results showed that SARS-CoV-2 diminished the detectable surfactant level. In this regard, clinical trials were conducted to evaluate the efficacy of exogenous surfactant to compensate the surfactant deficit and improve patients’ outcome [70,78,80]. There are also some reports on the effect of GLP-1 on human type 2 pneumocytes, which showed GLP-1RA could increase the production of phosphatidylcholine through the protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) pathways and ultimately increase the secretion of surfactant in the lung tissue [81]. Furthermore, evaluation of the long-term consequences of SARS-CoV-2 on infected patients showed that one of the most dangerous long-term outcomes could be the development of interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in a group of patients, who have experienced a severe phase of the disease [82,83].

Given the importance of this process and considering the fact that appropriate medications for IPF are not available, evaluating the effectiveness of potential medications for the treatment of these patients is necessary. A study on a mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis showed that GLP-1RA could reduce the expression of collagen and hydroxyproline and inhibit the enzymes involved in IPF formation, besides having a positive effect on surfactant production and inhibiting the activity of inflammatory cells and cytokines [84]. Bleomycin is a substance that can be used as to induce IPF in animal studies [85]. This increases the expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), which are effective in fibrous formation. Moreover, inhibition of the NF-κB pathway by GLP-1RA has been proposed to be effective in the IPF alleviation [86].

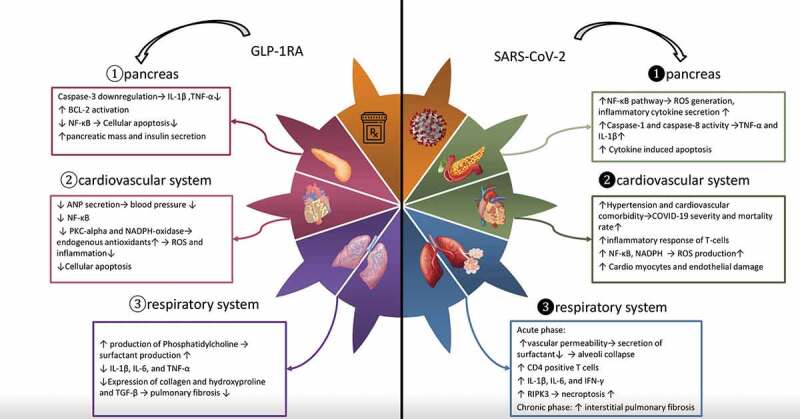

Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) contributes to the occurrence of fibrosis as well [87,88]. A study on human mesenchymal cells showed that reduction in the level of TGF-β could be considered as an action mechanism of anti-fibrotic effects of GLP-1 [89]. Therefore, GLP-1 can be a part of corresponding pathways in both acute and chronic phases of pulmonary injury. Further studies on the effectiveness of GLP-1RA in ALI and its long-term effects among patients who are infected by SARS-CoV-2 is of high value (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the effects of GLP-1RA and SARS-CoV-2 on the 1-Pancreatic cells 2 – Cardiovascular system and 3 – Respiratory system: Anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1RA such as inhibition of NF-?B pathway and reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokine production in comparison with the inflammatory and apoptotic effects of SARS-CoV-2 on various organs of the body mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines through NF-?b pathway and caspase activity

Abbreviations: GLP-1RA: glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; NF-?B: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancerof activated B cells; IL-1?: interleukin-1 beta; TNF-?: tumor necrosis factor alpha; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2; ANP: atrial natriuretic peptide; PKC: protein kinase C; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; ROS: reactive oxygen species; IL-6: interleukin 6; TGF-?: transforming growth factor beta; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; IFN-?: interferon gamma; RIPK3: receptor-interacting protein kinase-3.

10. Conclusion

GLP-1RA exerts their protective and anti-apoptotic effects on different organs of the body, including the cardiovascular, respiratory, and endocrine systems by inhibiting inflammatory pathways through decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion. According to various studies, positive effects of GLP-1 in attenuating the inflammatory status in chronic metabolic diseases, focusing on the use of GLP-1RA to regulate various comorbidities alongside the blood glucose control, especially in diabetic patients, could be beneficial.

In addition, the protective effects of GLP-1 in ALI require further investigations to clarify the effectiveness of using these medications in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.

It is worth considering that in a meta-analysis performed aiming to evaluate the safety of using GLP-1RA during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was determined that the administration of GLP-1RA is not a risk factor for respiratory tract infections or other complications such as ARDS, especially among patients with other comorbidities [90].

Due to the importance of understanding the determinants of the outcome in COVID-19 patients, various studies on the relationship between the type of antidiabetic medications and the outcomes of patients have been conducted [91]. For instance, results of a study on the 12,446 individuals with positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test showed that the 60-day mortality and hospitalization rates in patients who were taking both GLP-1RA and sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) were lower than those taking only DPP4 inhibitors [92]. In another study, the difference in COVID-19 mortality rate in patients getting different glucose-lowering agents, including GLP-1RA has been shown, however, to draw a firm conclusion and to identify the confounding factors, conducting more detailed clinical studies is necessary [93].

In general, although GLP-1RA is a well-known glucose modulating medications for diabetic patients, it is necessary to recognize its further potential benefits in the treatment and control of other comorbidities and metabolic disorders, besides its implications in the treatment of both acute and chronic phases of SARS-CoV-2 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

11. Expert opinion

Considering the fact that there is no definitive medication to treat the COVID-19 infection, conducting different studies to discover promising targets for designing and/or repurposing proper medications are necessary.

Given the promising results of GLP-1RA due to their anti-inflammatory and protective effects in combating the development of ARDS and AKI in animal studies, designing clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of different of GLP-1RA is of interest. For instance, liraglutide and dulaglutide, such as GLP-1RA, and different classes of DPP-4 inhibitors, including sitagliptin and saxagliptin are potential candidates to be evaluated in further clinical investigations to determine whether they could be a choice for medication regimens in the acute phase of COVID-19 infection. In addition, glucose homeostasis is disturbed in critically ill patients in the phase of severe inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis. Therefore, since it could cause reinforcing loops in exacerbating patients’ conditions, further investigation concerning the effects of GLP-1RA in controlling glucose homeostasis in critically ill patients is necessaryin particular, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It should also be noted that a large number of individuals have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 so far, and a percentage of them have experienced severe forms of the disease; therefore, a long-term view and attention to the chronic consequences and late-onset complications of the disease is important. In line with this, long-term pulmonary complications, especially IPF, that may be considered as a result of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection remained to be addressed. As mentioned earlier in the manuscript, previous studies on the animal models showed the anti-fibrotic effects of GLP-1RA in addition to their capability of stimulating the surfactant production. In this regard, evaluating the effectiveness of GLP-1RA in extended clinical trials, especially at this critical time of the pandemic, is needed to prevent or ameliorate the future burden of the disease.

However, in addition to the therapeutic effects of GLP-1RA in patients with COVID-19, it is also important to evaluate the effectiveness of GLP-1RA in controlling comorbidities and risk factors influencing the development of chronic inflammation in vulnerable individuals. In this regard, it is important to have a systematic approach to metabolic diseases, such as DM and atherosclerotic disorders. Accordingly, alongside controlling the blood sugar level, monitoring, and controlling the development of associated comorbidities such as NAFLD and obesity should be considered in the management of these patients. Therefore, we may be able to help attenuating the burden of the late-onset medical sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In general, from the authors’ point of view, GLP-1RA could be effective in different phases of COVID-19 infection. Before exposure to the virus, GLP-1RA is potentially effective in improving the prognosis of patients by controlling risk factors that could contribute to the development of detrimental comorbidities. In the acute phase of the disease, the effectiveness of these therapeutic agents in acute lung injury along with controlling the blood sugar homeostasis is probable. Finally, according to conducted animal studies that show the protective effects of GLP-1RA in fibrosis formation, considering GLP-1RA as potential treatment candidates in this phase of COVID-19 infection might be reasonable. In this regard, further detailed and extended studies with the aim of evaluating the characteristics and possible side effects of different GLP-1RA and DPP-4 inhibitors in the context of SARS-CoV-2 treatment are required. In addition, discovering highly effective types of GLP-1RA, which could be more specifically suitable for each phase of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, is of interest.

Article highlights

GLP-1RA represented protective properties against pancreatic beta-cells damage, caused by inflammation and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

GLP-1RA might be useful in modifying risk factors of developing severe COVID-19 complications, such as obesity, NAFLD, and cardiovascular disease.

GLP-1RA has been proposed as a potential therapeutic candidate during acute COVID-19 infection to reduce respiratory injuries.

GLP-1RA demonstrated promising results in the prevention of chronic lung injuries such as pulmonary fibrosis following a severe form of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers in this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Authors Contribution

All authors should have substantially contributed to the conception and design of the review article and interpreting the relevant literature and have been involved in writing the review article or revised it for intellectual content.

Abbreviations

GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1

GLP-1RA: glucagon-like peptide-1R receptor agonists

SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

RAAS: renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

DPP4: dipeptidyl-peptidase 4

NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha

IL-1β: interleukin 1 beta

IL-6: interleukin 6

DM: diabetes mellitus

VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

α-SMA: alpha-smooth muscle actin

TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta

Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2

LPS: lipopolysaccharides

SGLT2i: sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitor

ROS: reactive oxygen species

PCR: polymerase chain reaction

ANP: atrial natriuretic peptide

PKA: protein kinase A

PKC: protein kinase C

PKB: protein kinase B

NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

CRP: c-reactive protein

IFN-γ: interferon gamma

ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome

ALI: acute lung injury

IPF: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

CD4+: cluster of differentiation 4

Caspase: cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases

NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

RIPK3: receptor-interacting protein kinase-3

PI3K: phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase

PKC ζ: protein kinase C ζ

cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate

CREB: cAMP response element-binding protein

Bcl-xL: B-cell lymphoma-extra large

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. Addendum: a pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020Dec;588(7836):E6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.corona virus cases and deaths [updated 2021; cited]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?utm_campaign=homeAdvegas1?%22%20%5Cl%22countries (access date: 2021 Jun 26)

- 3.Riddle MC, Buse JB, Franks PW, et al. COVID-19 in people with diabetes: urgently needed lessons from early reports. Diabetes Care. 2020Jul;43(7):1378–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palaiodimos L, Chamorro-Pareja N, Karamanis D, et al. Diabetes is associated with increased risk for in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis comprising 18,506 patients. Hormones (Athens). 2021Jun;20(2):305–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diabetes. [cited 2021 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1

- 6.Zhu L, She ZG, Cheng X, et al. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020Jun2;31(6):1068–1077 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005Aug;11(8):875–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, McLellan JS.. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020 Mar 13;367(6483):1260–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean RG, Burrell LM. ACE2 and diabetic complications. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(26):2730–2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee YS, Jun HS. Anti-Inflammatory effects of GLP-1-based therapies beyond glucose control. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:3094642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This is a valuable systematic view of the anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1RA in various organs of the body.

- 11.Nadkarni P, Chepurny OG, Holz GG. Regulation of glucose homeostasis by GLP-1. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014;121:23–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceriello A, Novials A, Ortega E, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 reduces endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and oxidative stress induced by both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013Aug;36(8):2346–2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubino F, Amiel SA, Zimmet P, et al. New-onset diabetes in covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020Aug20;383(8):789–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamming I, Timens W, Ml B, et al. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004Jun;203(2):631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel VB, Parajuli N, Oudit GY. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in diabetic cardiovascular complications. Clin Sci (Lond). 2014Apr;126(7):471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romani-Perez M, Outeirino-Iglesias V, Moya CM, et al. Activation of the GLP-1 receptor by liraglutide increases ACE2 expression, reversing right ventricle hypertrophy, and improving the production of SP-A and SP-B in the lungs of type 1 diabetes rats. Endocrinology. 2015Oct;156(10):3559–3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valencia I, Peiro C, Lorenzo O, et al. DPP4 and ACE2 in diabetes and COVID-19: Therapeutic targets for cardiovascular complications? Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarkar J, Nargis T, Tantia O, et al. Increased plasma dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) activity is an obesity-independent parameter for glycemic deregulation in type 2 diabetes patients. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller JA, Gross R, Conzelmann C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects and replicates in cells of the human endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Nat Metab. 2021Feb;3(2):149–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Rivero Vaccari JC, Dietrich WD, Keane RW, et al. The Inflammasome in times of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:583373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Valle DM, Kim-Schulze S, Huang HH, et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020Oct;26(10):1636–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurung P, Kanneganti TD. Novel roles for caspase-8 in IL-1beta and inflammasome regulation. Am J Pathol. 2015Jan;185(1):17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandasamy M. NF-kappaB signalling as a pharmacological target in COVID-19: potential roles for IKKbeta inhibitors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2021Mar;394(3):561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gigoux V, Fourmy D. Acting on hormone receptors with minimal side effect on cell proliferation: a timely challenge illustrated with GLP-1R and GPER. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Zhu Y, Gao L, et al. Formononetin attenuates IL-1beta-induced apoptosis and NF-kappaB activation in INS-1 cells. Molecules. 2012Aug24;17(9):10052–10064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomita T. Apoptosis in pancreatic beta-islet cells in Type 2 diabetes. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2016Aug2;16(3):162–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hogan AE, Gaoatswe G, Lynch L, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue therapy directly modulates innate immune-mediated inflammation in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2014Apr;57(4):781–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Hansotia T, Yusta B, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling modulates beta cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003Jan3;278(1):471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farilla L, Bulotta A, Hirshberg B, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 inhibits cell apoptosis and improves glucose responsiveness of freshly isolated human islets. Endocrinology. 2003Dec;144(12):5149–5158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020May;94:91–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He XW, Lai JS, Cheng J, et al. [Impact of complicated myocardial injury on the clinical outcome of severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2020Jun24;48(6):456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Gill D, Walker J, et al. Myocardial injury and COVID-19: Possible mechanisms. Life Sci. 2020Jul15;253:117723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basso C, Leone O, Rizzo S, et al. Pathological features of COVID-19-associated myocardial injury: a multicentre cardiovascular pathology study. Eur Heart J. 2020Oct14;41(39):3827–3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chernyak BV, Popova EN, Prikhodko AS, et al. COVID-19 and oxidative stress. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2020Dec;85(12):1543–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei Y, Mojsov S. Tissue-specific expression of the human receptor for glucagon-like peptide-I: brain, heart and pancreatic forms have the same deduced amino acid sequences. FEBS Lett. 1995Jan30;358(3):219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim M, Platt MJ, Shibasaki T, et al. GLP-1 receptor activation and Epac2 link atrial natriuretic peptide secretion to control of blood pressure. Nat Med. 2013May;19(5):567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saraiva FK, Sposito AC. Cardiovascular effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014Oct22;13(1):142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiraki A, Oyama J, Komoda H, et al. The glucagon-like peptide 1 analog liraglutide reduces TNF-alpha-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2012Apr;221(2):375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piotrowski K, Becker M, Zugwurst J, et al. Circulating concentrations of GLP-1 are associated with coronary atherosclerosis in humans. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013Aug16;12(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grzegorowska O, Lorkowski J. Possible correlations between atherosclerosis, acute coronary syndromes and COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2020Nov21;9(11):3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeoh YK, Zuo T, Lui GC, et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2021Apr;70(4):698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuo T, Zhang F, Lui GCY, et al. Alterations in gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020Sep;159(3):944–955 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chhibber-Goel J, Gopinathan S, Sharma A. Interplay between severities of COVID-19 and the gut microbiome: implications of bacterial co-infections? Gut Pathog. 2021Feb25;13(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tian L, Jin T. The incretin hormone GLP-1 and mechanisms underlying its secretion. J Diabetes. 2016Nov;8(6):753–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamane S, Inagaki N. Regulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 sensitivity by gut microbiota dysbiosis. J Diabetes Investig. 2018Mar;9(2):262–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo C, Huang T, Chen A, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 improves insulin resistance in vitro through anti-inflammation of macrophages. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2016Nov21;49(12):e5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitra S, De A, Chowdhury A. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Younossi ZM, Golabi P, De Avila L, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2019Oct;71(4):793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Portincasa P, Krawczyk M, Smyk W, et al. COVID-19 and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: two intersecting pandemics. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020Oct;50(10):e13338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sachdeva S, Khandait H, Kopel J, et al. NAFLD and COVID-19: a pooled analysis. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;6:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lv X, Dong Y, Hu L, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) for the management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a systematic review. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2020Jul;3(3):e00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seghieri M, Christensen AS, Andersen A, et al. Future perspectives on GLP-1 receptor agonists and GLP-1/glucagon receptor co-agonists in the treatment of NAFLD. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar J, Memon RS, Shahid I, et al. Antidiabetic drugs and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and evidence map. Dig Liver Dis. 2021Jan;53(1):44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dougherty JA, Guirguis E, Thornby KA. A systematic review of newer antidiabetic agents in the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2021Jan;55(1):65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nigam P, Bhatt SP, Misra A, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is closely associated with sub-clinical inflammation: a case-control study on Asian Indians in North India. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e49286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foroughi M, Maghsoudi Z, Khayyatzadeh S, et al. Relationship between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and inflammation in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver. Adv Biomed Res. 2016;5(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeniova AO, Kucukazman M, Ata N, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is a strong predictor of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014Mar-Apr;61(130):422–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mazidi M, Karimi E, Rezaie P, et al. Treatment with GLP1 receptor agonists reduce serum CRP concentrations in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Diabetes Complications. 2017Jul;31(7):1237–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim J, Nam JH. Insight into the relationship between obesity-induced low-level chronic inflammation and COVID-19 infection. Int J Obes (Lond). 2020Jul;44(7):1541–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chu Y, Yang J, Shi J, et al. Obesity is associated with increased severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2020Dec2;25(1):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCarthy C, O’Donnell CP, Kelly NEW, et al. COVID-19 severity and obesity: are MAIT cells a factor? Lancet Respir Med. 2021May;9(5):445–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malavazos AE, Corsi Romanelli MM, Bandera F, et al. Targeting the adipose tissue in COVID-19. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020Jul;28(7):1178–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shah M, Vella A. Effects of GLP-1 on appetite and weight. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014Sep;15(3):181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inoue K, Maeda N, Kashine S, et al. Short-term effects of liraglutide on visceral fat adiposity, appetite, and food preference: a pilot study of obese Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011Dec1;10(1):109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fujishima Y, Maeda N, Inoue K, et al. Efficacy of liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue, on body weight, eating behavior, and glycemic control, in Japanese obese type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012Sep14;11(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee YS, Park MS, Choung JS, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and inflammation in an obese mouse model of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012Sep;55(9):2456–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seon MJ, Hwang SY, Son Y, et al. Circulating GLP-1 levels as a potential indicator of metabolic syndrome risk in adult women. Nutrients. 2021Mar6;13(3):865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This is a comprehensive article, which highlights potentials of GLP-1 as a benchmark for screening.

- 68.Badraoui R, Alrashedi MM, El-May MV, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: a life threatening associated complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection inducing COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020Aug;5:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maveddat A, Mallah H, Rao S, et al. Severe acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Int J Occup Environ Med. 2020Oct;11(4):157–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schousboe P, Wiese L, Heiring C, et al. Assessment of pulmonary surfactant in COVID-19 patients. Crit Care. 2020Sep7;24(1):552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar R, Lee MH, Mickael C, et al. Pathophysiology and potential future therapeutic targets using preclinical models of COVID-19. ERJ Open Res. 6. Oct2020; 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Catanzaro M, Fagiani F, Racchi M, et al. Immune response in COVID-19: addressing a pharmacological challenge by targeting pathways triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020May29;5(1):84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perrone LA, Szretter KJ, Katz JM, et al. Mice lacking both TNF and IL-1 receptors exhibit reduced lung inflammation and delay in onset of death following infection with a highly virulent H5N1 virus. J Infect Dis. 2010Oct15;202(8):1161–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li S, Zhang Y, Guan Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 triggers inflammatory responses and cell death through caspase-8 activation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020Oct9;5(1):235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bai Y, Lian P, Li J, et al. The active GLP-1 analogue liraglutide alleviates H9N2 influenza virus-induced acute lung injury in mice. Microb Pathog. 2021Jan;150:104645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akella A, Deshpande SB. Pulmonary surfactants and their role in pathophysiology of lung disorders. Indian J Exp Biol. 2013Jan;51(1):5–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma CC, Ma S. The role of surfactant in respiratory distress syndrome. Open Respir Med J. 2012;6(1):44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Islam A, Khan MA. Lung transcriptome of a COVID-19 patient and systems biology predictions suggest impaired surfactant production which may be druggable by surfactant therapy. Sci Rep. 2020Nov10;10(1):19395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Han S, Mallampalli RK. The role of surfactant in lung disease and host defense against pulmonary infections. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015May;12(5):765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Piva S, DiBlasi RM, Slee AE, et al. Surfactant therapy for COVID-19 related ARDS: a retrospective case-control pilot study. Respir Res. 2021Jan18;22(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vara E, Arias-Diaz J, Garcia C, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (7-36)amide stimulates surfactant secretion in human type II pneumocytes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001Mar;163(4):840–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gentile F, Aimo A, Forfori F, et al. COVID-19 and risk of pulmonary fibrosis: the importance of planning ahead. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020Sep;27(13):1442–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fraser E. Long term respiratory complications of covid-19. BMJ. 2020Aug;3(370):m3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fandino J, Toba L, Gonzalez-Matias LC, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonist ameliorates experimental lung fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2020Oct22;10(1):18091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moeller A, Ask K, Warburton D, et al. The bleomycin animal model: a useful tool to investigate treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(3):362–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gou S, Zhu T, Wang W, et al. Glucagon like peptide-1 attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, involving the inactivation of NF-kappaB in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014Oct;22(2):498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oda K, Yatera K, Izumi H, et al. Profibrotic role of WNT10A via TGF-beta signaling in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2016Apr12;17(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saito A, Horie M, Micke P, et al. The role of TGF-beta signaling in lung cancer associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018Nov15;19(11):3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li W, Cui M, Wei Y, et al. Inhibition of the expression of TGF-beta1 and CTGF in human mesangial cells by exendin-4, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30(3):749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Patoulias D, Boulmpou A, Imprialos K, et al. [Meta-analysis evaluating the risk of respiratory tract infections and acute respiratory distress syndrome with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in cardiovascular outcome trials: useful implications for the COVID-19 pandemic]. Rev Clin Esp. 2021Apr;27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This is an important meta-analysis evaluating the saftey of GLP-1RA especially in respirtaoty tract infections or other complications in the time of COVID-19 pandemic.

- 91.Schernthaner G. Can glucose-lowering drugs affect the prognosis of COVID-19 in patients with type 2 diabetes? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021May;9(5):251–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Anna R. Kahkoska 1 TJA, G Caleb Alexander 3 4 5, Tellen D Bennett 6, Christopher G Chute 7, Melissa A Haendel 8, Klara R Klein 9, Hemalkumar Mehta 3 4, Joshua D Miller 10, Richard A Moffitt 11, Til Stürmer 12, Kajsa Kvist 2, John B Buse, N3C consortium. association between glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor use and COVID-19 outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Khunti K, Knighton P, Zaccardi F, et al. Prescription of glucose-lowering therapies and risk of COVID-19 mortality in people with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide observational study in England. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021May;9(5):293–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]