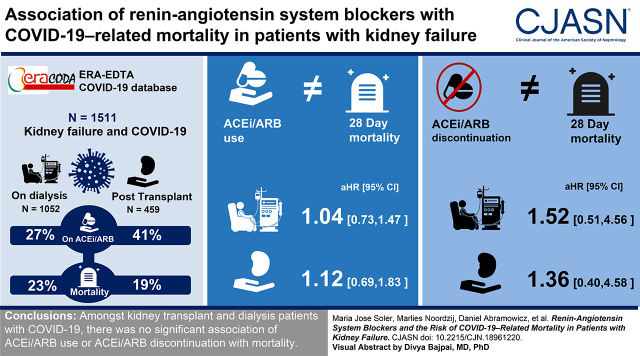

Visual Abstract

Keywords: COVID-19, renin angiotensin system, dialysis, kidney transplantation, kidney failure

Abstract

Background and objectives

There is concern about potential deleterious effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Patients with kidney failure, who often use ACEis/ARBs, are at higher risk of more severe COVID-19. However, there are no data available on the association of ACEi/ARB use with COVID-19 severity in this population.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

From the European Renal Association COVID-19 database (ERACODA), we retrieved data on kidney transplant recipients and patients on dialysis who were affected by COVID-19, between February 1 and October 1, 2020, and had information on 28-day mortality. We used Cox proportional-hazards regression to calculate hazard ratios for the association between ACEi/ARB use and 28-day mortality risk. Additionally, we studied the association of discontinuation of these agents with 28-day mortality.

Results

We evaluated 1511 patients: 459 kidney transplant recipients and 1052 patients on dialysis. At diagnosis of COVID-19, 189 (41%) of the transplant recipients and 288 (27%) of the patients on dialysis were on ACEis/ARBs. A total of 88 (19%) transplant recipients and 244 (23%) patients on dialysis died within 28 days of initial presentation. In both groups of patients, there was no association between ACEi/ARB use and 28-day mortality in both crude and adjusted models (in transplant recipients, adjusted hazard ratio, 1.12; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.69 to 1.83; in patients on dialysis, adjusted hazard ratio, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.73 to 1.47). Among transplant recipients, ACEi/ARB discontinuation was associated with a higher mortality risk after adjustment for demographics and comorbidities, but the association was no longer statistically significant after adjustment for severity of COVID-19 (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.36; 95% CI, 0.40 to 4.58). Among patients on dialysis, ACEi/ARB discontinuation was not associated with mortality in any model. We obtained similar results across subgroups when ACEis and ARBs were studied separately, and when other outcomes for severity of COVID-19 were studied, e.g., hospital admission, admission to the intensive care unit, or need for ventilator support.

Conclusions

Among kidney transplant recipients and patients on dialysis with COVID-19, there was no significant association of ACEi/ARB use or discontinuation with mortality.

Introduction

Renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade, either by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), is the first-choice treatment for patients with heart failure, myocardial infarction, and proteinuric kidney disease. Over the past 2 decades, several studies have suggested that RAS blockade is capable of increasing ACE2 expression in different tissues, including the heart, vasculature, and lungs (1–3). In particular, circulating ACE2 activity is increased in patients on dialysis who are treated with ARBs (3). Coronaviruses use ACE2 as a receptor to enter type II pneumocytes (4); therefore, there is a theoretic concern that ACEi/ARB use may lead to a more severe clinical course after infection with coronaviruses. Conversely, potential protective effects have also been described (5). Fang et al. (6) hypothesized that, in theory, patients with hypertension, diabetes, or cardiac diseases treated with RAS blockers might be at higher risk for more severe disease when infected with the novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Without evidence to support this hypothesis, several professional societies—including the European Society of Hypertension, the American College of Physicians, and the European Renal Association (ERA)—issued statements recommending that ACEis/ARBs be continued in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), while simultaneously strongly advocating for research to be undertaken to elucidate any potential role of ACEis/ARBs as determinants of COVID-19 severity (7).

COVID-19 is a new disease that has spread rapidly across the world since its discovery in 2019 (7). Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) aiming to assess the effect of ACEi/ARB discontinuation or initiation on COVID-19–related outcomes are currently ongoing, and the results of one, not focused on patients with kidney disease, were recently made public (7). Observational clinical data on this topic are scarce and limited to non–kidney disease populations. Of note, the use of ACEis/ARBs is higher among patients with CKD and usage increases with CKD severity. Moreover, patients with CKD are at a particularly higher risk of developing severe COVID-19, a risk that is exponentially higher with the severity of CKD (8,9). For these reasons, the nephrology community urgently needs to ascertain if RAS blockade can, at least in part, explain the severity of COVID-19 in this patient population.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a European database (ERACODA) was established to investigate the course and outcome of COVID-19 in patients living with a kidney transplant or those on maintenance dialysis therapy (5,10). This database was used to investigate the association between the use of ACEis/ARBs and the risk of 28-day mortality in patients with kidney failure and COVID-19. Additionally, we studied the effect of ACEi/ARB discontinuation, at the point of hospital admission for COVID-19, on 28-day mortality risk.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This observational study included information from the ERACODA database, which is endorsed by the ERA– European Dialysis and Transplantation Association (ERA-EDTA). The ERACODA database was established in March 2020 and currently involves the cooperation of approximately 200 physicians, representing 128 centers in 28 countries, mostly in Europe or countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Data are gathered on adult patients (≥18 years old) with kidney failure, either on long-term dialysis or with a functioning kidney allograft, who have been diagnosed with COVID-19 on the basis of a positive result on a real-time PCR assay of nasal or pharyngeal swab specimens, and/or compatible findings on a computed tomography scan of the lungs. Data are collected from outpatients and patients who are hospitalized. The physicians responsible for these patients’ care register detailed demographic data, including information pertaining to disease severity, treatment, and outcomes.

The ERACODA database is hosted at the University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands, and uses REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) software (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN) for data collection (5). Any identifiable patient information is stripped from each record, and data are stored pseudonymized. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University Medical Center Groningen (The Netherlands), who deemed the collection and analysis of data exempt from ethics review in the context of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO).

This observational study was designed by the ERACODA Working Group who also runs the database assisted by a Management Team and an Advisory Board (members listed in the Acknowledgments).

Data Collection

Patients on dialysis and transplant recipients who presented with COVID-19 between February 1 and October 1, 2020, and for whom there was information on status 28 days after initial presentation, were included in this analysis. The primary study outcome was 28-day mortality. Secondary outcomes were hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), and ventilator support. Outcomes were recorded with end of follow-up at day 28, with the last follow-up data entered on October 29, 2020.

We collected detailed information on patient characteristics (including demographics, height, weight, frailty score, comorbidities, and medication use) and COVID-19–related characteristics (the reason for COVID-19 screening, presenting symptoms, vital signs, and laboratory test results) at presentation. The use of ACEis/ARBs was recorded on two occasions: at presentation and when the dosing of these drugs was changed or discontinued during the first 48 hours after hospital admission. For the primary analysis, patients who were treated with ACEis/ARBs at presentation were classified as users, irrespective of whether they discontinued ACEi/ARB use within 48 hours of hospital admission. For an additional analysis, users who discontinued ACEi/ARB use within 48 hours of hospital admission were classified as discontinuers, and those who continued were classified as continuers.

Additionally, data on change in dosing or discontinuation of immunosuppressive drugs, and the start of anti-inflammatory therapy and antiviral therapy, were collected. Antiviral medications referred to the use of hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, remdesivir, IFN, azithromycin, or other antiviral medications. Anti-inflammatory medications referred to the use of tocilizumab, anakinra, high-dose steroids, or other anti-inflammatory medications. Frailty was assessed on a scale of one to nine on the basis of the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS). The CFS uses clinical descriptors and pictographs to generate a frailty score for a patient; a score of one represents very fit and score of nine represents terminally ill. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Obesity was defined as a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2. eGFR was estimated with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation using levels of serum creatinine collected at presentation. Comorbidities were recorded from patient records.

Statistical Analyses

The baseline characteristics of the patients included in the study are presented according to ACEi/ARB use for patients on dialysis and transplant recipients separately. Continuous data are presented as mean±SD; non-normally distributed data are presented as median with interquartile range. Categoric data are presented as percentages. Characteristics between groups were compared using the t test for continuous variables (Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data) and Pearson chi-squared statistics for categoric variables.

The association of ACEi/ARB use (versus nonuse) with 28-day mortality and secondary outcomes was examined in patients on dialysis and transplant recipients separately. Cumulative survival probabilities were plotted in Kaplan–Meier curves and were compared using the log-rank test for 28-day mortality. The cumulative incidence function was calculated for secondary outcomes, given the competing risk from mortality. Cox proportional-hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the risk of primary and secondary outcomes. To account for the competing risk from mortality, the cause-specific hazard was calculated for secondary outcomes.

Multiple models were constructed to account for potential confounders. Model 1 is a crude (unadjusted) model. In model 2, we adjusted for age, sex, and CFS score (i.e., the most important factors related to prognosis in previous analyses of the ERACODA database). In model 3, we additionally adjusted for systolic BP, diabetes, and heart failure (comorbidities predisposing for the use of ACEis/ARBs). Model 4 was further adjusted for anti-inflammatory therapy and antiviral therapy. For the primary outcome (28-day mortality), we also investigated the interaction between the type of KRT and ACEi/ARB use. We did not adjust for disease severity in this analysis because use of ACEis/ARBs may be responsible for disease severity. Therefore, disease severity is in the causal pathway between ACEi/ARB use and outcomes, and was considered as a mediator and not as a confounder. The assumption of proportionality was confirmed by visual inspection of Schoenfeld residuals.

To assess the robustness of our findings, we performed additional analyses. First, in model 5, we adjusted for variables that showed a statistically significant difference in their distribution between ACEi/ARB users and nonusers, except variables related to COVID-19 disease severity. Disease severity may be a consequence of use or nonuse of ACEis/ARBs and might, therefore, be causal. Second, we examined our results for kidney transplant recipients when additionally adjusting for baseline kidney function. Third, we investigated whether the association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality varies across subgroups of age (<65 versus ≥65 years); sex (male versus female); and obesity, hypertension, diabetes, or heart failure status (yes versus no). Fourth, we examined whether any association with 28-day mortality differed between ACEi users and ARB users. Fifth, we excluded patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19 only on the basis of computed tomography scan or x-ray findings and repeated our analyses. Further, to account for a potential selection bias, we repeated the analyses in patients who were hospitalized only. We also investigated the association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality in propensity score–matched users and nonusers of ACEis/ARBs.

Finally, we examined characteristics of continuers and discontinuers of ACEis/ARBs and examined the association of continuation/discontinuation of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality. This analysis was performed only in patients who were hospitalized because a decision to continue or discontinue treatment is more likely in such patients. We analyzed 448 patients who were hospitalized, on ACEis/ARBs, and had information on ACEi/ARB continuation or discontinuation upon hospitalization. Disease severity could be the reason for ACEi/ARB discontinuation in these patients; therefore, in model 5, we adjusted further for factors related to COVID-19 disease severity, including cough, shortness of breath, fever, pulse rate, respiration rate, lymphocyte count, C-reactive protein, and >25% serum creatinine rise compared with pre–COVID-19 baseline.

Patients with missing information on day-28 vital status and ACEi/ARB use were excluded from the analysis. To assess differences between those included in analysis and those with missing information, these patients’ age, sex, frailty, and comorbidities and disease severity characteristics were compared. We used pairwise deletion to compute missing data on other variables included in the analysis (frailty, 38 in transplant recipients, 137 in patients on dialysis; systolic BP, 75 in transplant recipients, 203 in patients on dialysis; antiviral drug use, three in transplant recipients, four in patients on dialysis; anti-inflammatory drug use, three in transplant recipients, three in patients on dialysis). As a confirmatory analysis, association was investigated after multiple imputation using chained equations.

All analyses were performed using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A two-sided P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

As of October 29, 2020, data had been collected on 1804 patients. Of these patients, 1511 had complete information on vital status at day 28 and ACEi/ARB use (Supplemental Figure 1). There were a total of 459 kidney transplant recipients and 1,052 patients on dialysis; 189 (41%) transplant recipients and 288 (27%) patients on dialysis were on ACEi/ARB treatment.

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics for users and nonusers of ACEis/ARBs in kidney transplant recipients and patients on dialysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of kidney transplant recipients and patients on dialysis with COVID-19, overall and according to ACEi/ARB use status (nonusers/users)

| Characteristics | Recipients of Kidney Transplant | Patients on Dialysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n=459) | ACEi/ARB Use Status | All (n=1052) | ACEi/ARB Use Status | |||

| Nonusers (n=270) | Users (n=189) | Nonusers (n=764) | Users (n=288) | |||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Male sex, n (%) | 276 (60) | 154 (57) | 122 (65) | 641 (61) | 440 (58) | 201 (70) |

| Age (yr), mean±SD | 59±13 | 60±14 | 58±12 | 66±15 | 67±14 | 63±16 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 27±5 | 27±5 | 27±5 | 27±5 | 27±6 | 27±5 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Asian | 12 (3) | 4 (2) | 8 (4) | 35 (3) | 18 (2) | 17 (6) |

| Black | 33 (7) | 24 (9) | 9 (5) | 55 (5) | 28 (4) | 27 (9) |

| White | 395 (85) | 228 (84) | 167 (88) | 903 (86) | 674 (88) | 229 (80) |

| Other or unknown | 19 (4) | 14 (5) | 5 (3) | 59 (6) | 44 (6) | 15 (5) |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | ||||||

| Current | 20 (4) | 16 (6) | 4 (2) | 80 (7) | 48 (6) | 32 (11) |

| Prior | 110 (24) | 67 (25) | 43 (23) | 237 (23) | 169 (22) | 68 (24) |

| Never | 236 (51) | 137 (51) | 99 (52) | 490 (47) | 358 (47) | 490 (46) |

| Unknown | 93 (20) | 50 (19) | 43 (23) | 245 (23) | 189 (25) | 56 (19) |

| Clinical frailty scale (AU), mean±SD | 3.0±1.6 | 3.2±1.7 | 2.8±1.5 | 4.0±1.8 | 4.1±1.8 | 3.7±1.8 |

| Patient identification, n (%)a | ||||||

| Symptoms only | 301 (88) | 171 (88) | 130 (88) | 559 (65) | 391 (62) | 168 (70) |

| Symptoms and contact | 28 (8) | 14 (7) | 14 (10) | 145 (17) | 111 (18) | 34 (14) |

| No symptoms but contact | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 76 (9) | 55 (9) | 21 (9) |

| Routine screening | 11 (3) | 9 (5) | 2 (1) | 85 (10) | 69 (11) | 16 (7) |

| COVID-19 test result (positive), n (%) | 425 (94) | 249 (95) | 176 (94) | 994 (97) | 723 (97) | 271 (95) |

| X-ray anormality (yes), n (%) | 219 (49) | 122 (46) | 97 (52) | 317 (31) | 226 (30) | 91 (33) |

| CT scan anormality (yes), n (%) | 145 (32) | 82 (31) | 63 (34) | 330 (32) | 246 (33) | 84 (30) |

| Asymptomatic, n (%)b | 9 (2) | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 158 (15) | 115 (15) | 43 (15) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Obesity (BMI>30 kg/m2) c | 86 (22) | 47 (20) | 39 (24) | 202 (22) | 143 (22) | 59 (24) |

| Hypertension | 385 (84) | 206 (76) | 179 (95) | 883 (84) | 619 (81) | 264 (92) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 141 (31) | 88 (33) | 53 (28) | 448 (43) | 307 (40) | 141 (49) |

| Coronary artery disease | 91 (20) | 60 (22) | 31 (16) | 351 (33) | 251 (33) | 100 (35) |

| Heart failure | 39 (9) | 29 (11) | 10 (5) | 252 (24) | 177 (23) | 75 (26) |

| Chronic lung disease | 42 (9) | 31 (11) | 11 (6) | 145 (14) | 113 (15) | 32 (11) |

| Active malignancy | 27 (6) | 15 (6) | 12 (6) | 70 (7) | 53 (7) | 17 (6) |

| Autoimmune disease | 24 (5) | 15 (6) | 9 (5) | 50 (5) | 37 (5) | 13 (5) |

| Primary kidney disease, n (%) | ||||||

| Primary GN | 90 (20) | 56 (21) | 34 (18) | 159 (15) | 129 (17) | 30 (11) |

| Pyelonephritis | 18 (4) | 11 (4) | 7 (4) | 16 (2) | 14 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Interstitial nephritis | 21 (5) | 15 (6) | 6 (3) | 36 (3) | 28 (4) | 8 (3) |

| Hereditary kidney disease | 61 (14) | 31 (12) | 30 (16) | 80 (8) | 59 (8) | 21 (7) |

| Congenital diseases | 16 (4) | 7 (3) | 9 (5) | 16 (2) | 12 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Vascular diseases | 38 (8) | 21 (8) | 17 (9) | 141 (13) | 109 (14) | 32 (11) |

| Secondary glomerular disease | 22 (5) | 10 (4) | 12 (6) | 70 (7) | 53 (7) | 17 (6) |

| Diabetic kidney disease | 60 (13) | 41 (16) | 19 (10) | 260 (25) | 172 (23) | 88 (31) |

| Other | 54 (12) | 29 (11) | 25 (13) | 186 (18) | 125 (16) | 61 (21) |

| Unknown | 68 (15) | 41 (16) | 27 (15) | 84 (8) | 62 (8) | 22 (8) |

| Hemodialysis, n (%) | NA | NA | NA | 1000 (95) | 733 (96) | 267 (93) |

| Peritoneal dialysis, n (%) | NA | NA | NA | 52 (5) | 31 (4) | 21 (7) |

| Residual diuresis ≥200 ml/d, n (%) | NA | NA | NA | 343 (33) | 222 (30) | 121 (42) |

| Transplant waiting list status, n (%) | ||||||

| Active on waiting list | NA | NA | NA | 102 (10) | 69 (9) | 33 (11) |

| In preparation | NA | NA | NA | 102(10) | 64(8) | 38 (13) |

| Temporarily not on list | NA | NA | NA | 86 (8) | 54 (7) | 32 (11) |

| Not transplantable | NA | NA | NA | 593 (56) | 465 (61) | 128 (44) |

| Unknown | NA | NA | NA | 169 (16) | 112 (15) | 57 (20) |

| Time since transplantation, n (%) | ||||||

| <1 year | 29 (6) | 28 (11) | 1 (1) | NA | NA | NA |

| 1–5 years | 151 (33) | 99 (37) | 52 (28) | NA | NA | NA |

| >5 years | 276 (61) | 140 (52) | 136 (72) | NA | NA | NA |

| Medication use | ||||||

| Use of immunosuppressive medication, n (%) | ||||||

| Prednisone | 393 (86) | 239 (89) | 154 (81) | NA | NA | NA |

| Tacrolimus | 360 (78) | 215 (80) | 145 (77) | NA | NA | NA |

| Cyclosporine | 47 (10) | 26 (10) | 21 (11) | NA | NA | NA |

| Mycophenolate | 311 (68) | 183 (68) | 128 (68) | NA | NA | NA |

| Azathioprine | 19 (4) | 13 (5) | 6 (3) | NA | NA | NA |

| mTOR inhibitor | 64 (14) | 29 (11) | 35 (19) | NA | NA | NA |

| Disease-related characteristics | ||||||

| Presenting symptoms, n (%) | ||||||

| Sore throat | 61 (13) | 37 (14) | 24 (13) | 127 (12) | 84 (11) | 43 (15) |

| Cough | 295 (64) | 161 (60) | 134 (71) | 525 (50) | 379 (50) | 146 (51) |

| Shortness of breath | 194 (42) | 110 (41) | 84 (44) | 357 (34) | 270 (35) | 87 (30) |

| Fever | 334 (73) | 190 (71) | 144 (76) | 630 (60) | 454 (60) | 176 (61) |

| Headache | 74 (16) | 36 (13) | 38 (20) | 113 (11) | 71 (9) | 42 (15) |

| Nausea or vomiting | 74 (16) | 45 (17) | 29 (15) | 109 (10) | 72 (9) | 37 (13) |

| Diarrhea | 133 (29) | 78 (29) | 55 (29) | 130 (12) | 98 (13) | 32 (11) |

| Myalgia or arthralgia | 125 (27) | 71 (26) | 54 (29) | 210 (20) | 145 (19) | 65 (23) |

| Vital signs | ||||||

| Temperature (°C), mean±SD | 37.5±1.1 | 37.4±1.1 | 37.7±1.1 | 37.5±1.1 | 37.4±1.0 | 37.5±1.1 |

| Respiration rate (per min), mean±SD | 21±7 | 21±7 | 21±7 | 19±5 | 19±5 | 20±5 |

| Oxygen saturation in room air (%), mean±SD | 94±8 | 94±6 | 93±10 | 94±5 | 93±5 | 94±5 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg), mean±SD | 132±21 | 132±22 | 132±19 | 137±26 | 135±25 | 143±28 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg), mean±SD | 77±15 | 77±16 | 77±13 | 75±15 | 74±15 | 78±16 |

| Pulse rate (BPM), mean±SD | 86±17 | 86±18 | 86±15 | 82±15 | 82±15 | 82±15 |

| Laboratory test results | ||||||

| Creatinine increase (>25%), n (%) | 136 (30) | 78 (29) | 58 (31) | — | — | — |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73m2), median (IQR) | 36 (21–53) | 36 (21–55) | 37 (23–49) | |||

| Lymphocytes (×1000/µl), median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) |

| CRP (mg/L), median (IQR) | 44 (10–97) | 38 (8–96) | 49 (14–97) | 25 (6–75) | 25 (6–76) | 27 (6–72) |

Continuous variables are reported as mean±SD or median (IQR). Continuation/discontinuation groups were compared using t, Wilcoxon, or chi-squared test as appropriate. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ACEi/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CT, computed tomography; NA, not applicable; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; BPM, beats per minute; IQR, interquartile range; CRP, C-reactive protein.

342 patients had information on method of patient identification among transplant recipients, and 865 among dialysis patients.

COVID-19 test positive but without cough, sore throat, cough, shortness of breath, fever, headache, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, myalgia/arthralgia.

392 patients had information on obesity among transplant recipients, and 915 among dialysis patients.

The kidney transplant recipients included in the study were predominantly male (60%), with an average age of 59 years. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (84%) and diabetes (31%). The characteristics of ACEi/ARB users and nonusers were broadly comparable, although ACEi/ARB users were less frail, with a higher prevalence of hypertension and lower prevalence of heart failure and chronic lung disease. They had been transplanted for a longer period, had higher body temperature, and were less often on prednisone and more often on mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.

Patients on dialysis were, on average, 66 years old, and the majority were male (61%). ACEi/ARB users were younger; less frail; more often males and current smokers; had higher systolic and diastolic BP; and higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and diabetic kidney disease. They were also more likely to be on peritoneal dialysis and to have residual diuresis.

Association with 28-Day Mortality

In transplant recipients, 28-day mortality was 17% (95% CI, 13% to 24%) in ACEi/ARB users and 20% (95% CI, 16% to 26%) in nonusers. In patients on dialysis, these numbers were 21% (95% CI, 17% to 26%) and 24% (95% CI, 21% to 27%), respectively (Supplemental Table 1).

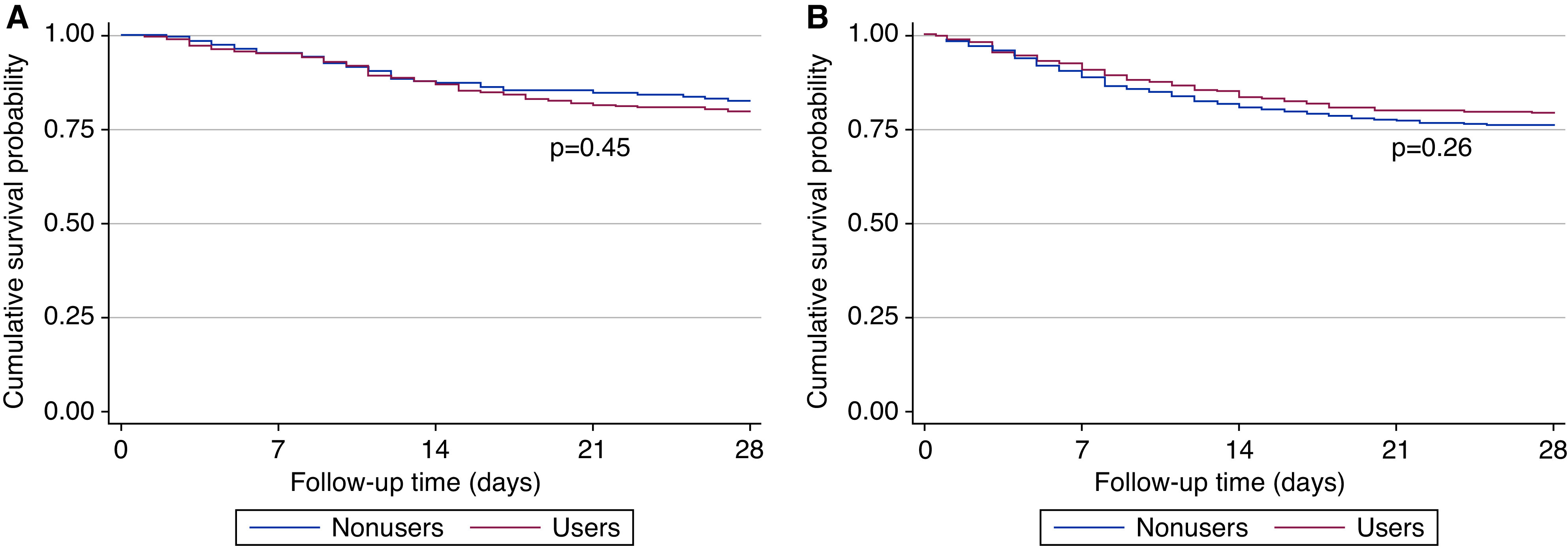

There was no statistically significant difference in cumulative survival probabilities between ACEi/ARB users and nonusers (P=0.45 in transplant recipients and P=0.26 in patients on dialysis) (Figure 1). In transplant recipients, Cox regression analysis indicated no statistically significant association between ACEi/ARB use and 28-day mortality. This association was not statistically significant in the crude model or in any of the multivariable adjusted models (e.g., model 4, HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.83; Table 2). Results were similar among patients on dialysis (see model 4, HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.73 to 1.47; Table 2). For the interaction between type of KRT and ACEi/ARB use status, P=0.88. Visualization of Schoenfeld residuals did not indicate a violation of the proportional-hazards assumption (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Cumulative survival probability in transplant recipients and patients on dialysis among those using (users) and those not using (nonusers) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers. (A) transplant recipients, (B) patients on dialysis.

Table 2.

Association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality

| Model | Recipients of Kidney Transplant (n=459) | Patients on Dialysis (n=1052) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonusers | Users | P Value | Nonusers | Users | P Value | |

| Event rate (events)a | 5.8 (55) | 4.9 (33) | 7.2 (184) | 6.0 (60) | ||

| Model 1b | Reference | 0.85 (0.55 to 1.31) | 0.46 | Reference | 0.85 (0.63 to 1.13) | 0.27 |

| Model 2c | Reference | 1.03 (0.65 to 1.64) | 0.89 | Reference | 1.05 (0.75 to 1.45) | 0.79 |

| Model 3d | Reference | 1.11 (0.69 to 1.81) | 0.66 | Reference | 1.04 (0.73 to 1.47) | 0.82 |

| Model 4e | Reference | 1.12 (0.69 to 1.83) | 0.64 | Reference | 1.04 (0.73 to 1.47) | 0.84 |

Presented are the hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) in transplant recipients and patients on dialysis, separately, unless otherwise indicated. ACEi/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker.

Event rate (events) per 100 person-weeks.

Model 1, crude.

Model 2, model 1 plus age, sex, and frailty.

Model 3, model 2 plus systolic BP, diabetes, and heart failure.

Model 4, model 3 plus anti-inflammatory therapy and antiviral therapy.

Association with Hospitalization, ICU Admission, and Ventilator Support

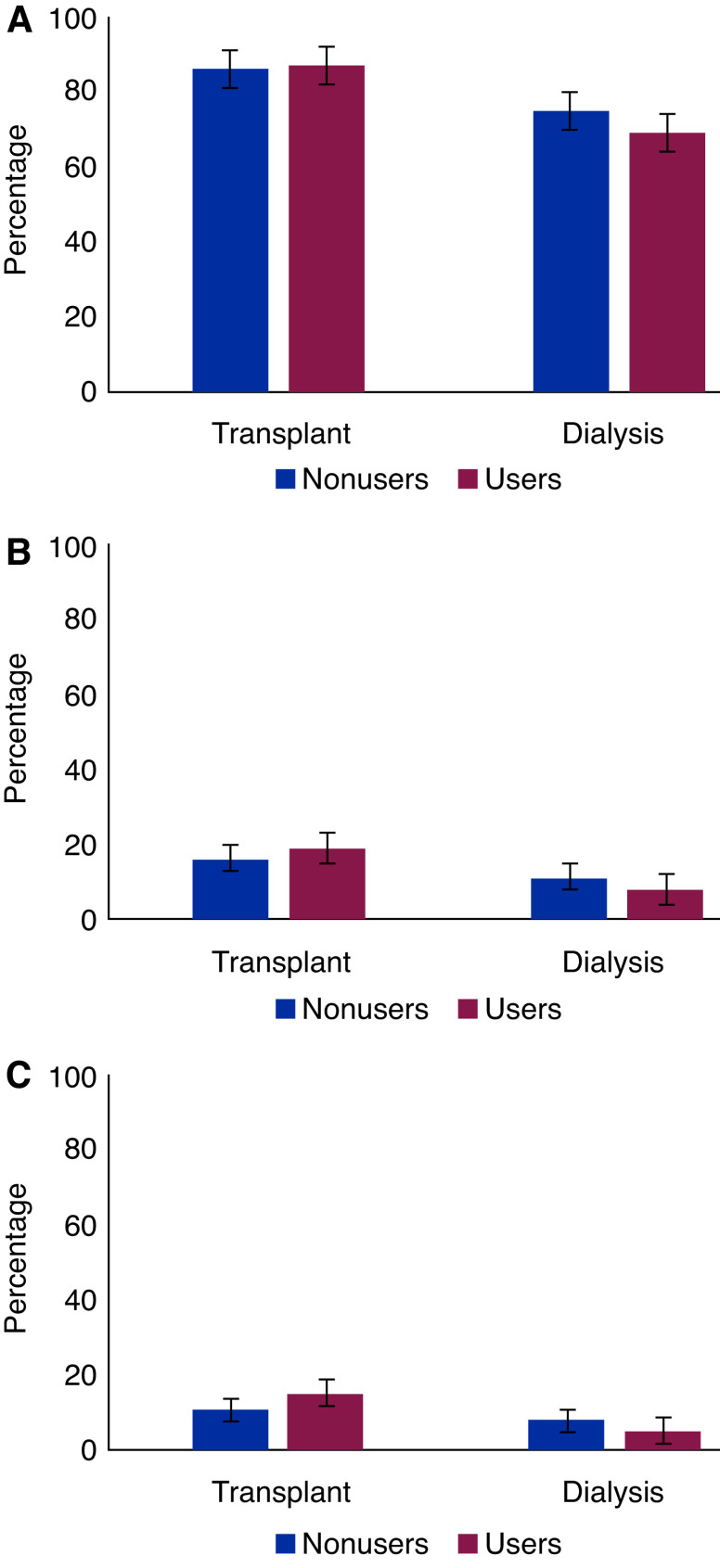

Distribution of hospitalization, ICU admission, and ventilator support among ACEi/ARB users and nonusers is shown in Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 1.

Figure 2.

Distribution of (A) hospitalization, (B) admission to the intensive care unit, and (C) ventilator support in patients on dialysis and transplant recipients by use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers.

There was no statistically significant difference in cumulative outcome probabilities between ACEi/ARB users and nonusers for hospitalization, ICU admission, or ventilator support (Supplemental Figures 3–5). Similar to the association with 28-day mortality, in the fully adjusted model, ACEi/ARB use was not associated with any of the secondary outcomes in transplant recipients and patients on dialysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of ACEi/ARB use with incidence of the secondary outcomes hospitalization, ICU admission, and ventilator support

| Model | Recipients of Kidney Transplant (n=459) | Patients on Dialysis (n=1047) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonusers | Users | P Value | Nonusers | Users | P Value | |

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| Event rate (events)a | 115.9 (219) | 136.5 (160) | 64.9 (542) | 47.7 (182) | ||

| Model 1b | Reference | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.27) | 0.71 | Reference | 0.85 (0.72 to 1.01) | 0.06 |

| Model 2c | Reference | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.29) | 0.71 | Reference | 0.85 (0.71 to 1.02) | 0.08 |

| Model 3d | Reference | 1.05 (0.84 to 1.31) | 0.66 | Reference | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.00) | 0.05 |

| Model 4e | Reference | 1.04 (0.83 to 1.30) | 0.74 | Reference | 0.89 (0.73 to 1.08) | 0.23 |

| ICU admission | ||||||

| Event rate (events)a | 4.9 (42) | 5.9 (35) | 3.2 (77) | 2.4 (23) | ||

| Model 1b | Reference | 1.22 (0.78 to 1.91) | 0.39 | Reference | 0.78 (0.49 to 1.24) | 0.29 |

| Model 2c | Reference | 1.29 (0.81 to 2.06) | 0.28 | Reference | 0.81 (0.49 to 1.33) | 0.40 |

| Model 3d | Reference | 1.39 (0.87 to 2.24) | 0.17 | Reference | 0.66 (0.38 to 1.15) | 0.14 |

| Model 4e | Reference | 1.28 (0.79 to 2.06) | 0.31 | Reference | 0.73 (0.41 to 1.30) | 0.29 |

| Ventilator support | ||||||

| Event rate (events)a | 3.4 (30) | 4.4 (27) | 2.3 (57) | 1.5 (14) | ||

| Model 1b | Reference | 1.31 (0.78 to 2.21) | 0.30 | Reference | 0.64 (0.36 to 1.15) | 0.14 |

| Model 2c | Reference | 1.33 (0.77 to 2.28) | 0.31 | Reference | 0.71 (0.38 to 1.31) | 0.27 |

| Model 3d | Reference | 1.47 (0.85 to 2.53) | 0.17 | Reference | 0.65 (0.34 to 1.25) | 0.20 |

| Model 4e | Reference | 1.41 (0.81 to 2.46) | 0.22 | Reference | 0.77 (0.40 to 1.51) | 0.45 |

Presented are the hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) in transplant recipients and patients on dialysis, separately, unless otherwise indicated. ACEi/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; ICU, intensive care unit.

Event rate per 100 person-weeks.

Model 1, crude.

Model 2, model 1 plus age, sex, and frailty.

Model 3, model 2 plus systolic BP, diabetes, and heart failure.

Model 4, model 3 plus anti-inflammatory therapy and antiviral therapy.

Additional Analyses

Further adjustment for variables that showed a statistically significant difference in their distribution between ACEi/ARB users and nonusers resulted in similar findings regarding association with primary and secondary outcomes (Supplemental Table 2). When additionally adjusting for kidney function in model 4, the HR for the association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality was 1.08 (95% CI, 0.66 to 1.77) in kidney transplant recipients. The association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality did not vary across subgroups by age (<65/≥65 years), sex (male/female), obesity status (yes/no), hypertension status (yes/no), diabetes status (yes/no), or heart failure status (yes/no); for interaction for all subgroups, P>0.05) (Supplemental Figure 6). Also, the interaction between ACEi and ARB use for association with 28-day mortality in the fully adjusted model was not statistically significant among transplant recipients and patients on dialysis (for interaction, P=0.99 among transplant recipients and patients on dialysis). In an analysis of patients diagnosed solely on the basis of a COVID-19 test and in an analysis of patients who were hospitalized only, the results were similar to the overall results (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). When comparing propensity score–matched users and nonusers of ACEis/ARBs, the HR for the association of ACEi/ARB use with our primary outcome (i.e., 28-day mortality) was 1.05 (95% CI, 0.65 to 1.70) in transplant recipients and 1.02 (95% CI, 0.72 to 1.46) in patients on dialysis. A comparison of continuers versus discontinuers showed that, among transplant recipients, the group that discontinued ACEi/ARB use had a higher respiratory rate, higher prevalence of shortness of breath, and worsening creatinine (>25%). Among patients on dialysis, the group that discontinued ACEi/ARB use had a higher prevalence of obesity and cough, and had a higher temperature, respiration rate, and pulse rate (Supplemental Table 5). Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis in transplant recipients indicated a significantly higher risk of 28-day mortality in discontinuers compared with continuers in a crude model (model 1) and multivariable models (models 2–4), but this association was no longer statistically significant when adjusted for COVID-19 severity–related variables on admission (model 5, Table 4). Among patients on dialysis, this association was not statistically significant in any of the models (Table 4). Regarding data completeness, characteristics were generally comparable between those included in the analysis and those with missing information (Supplemental Table 6). Characteristics were also comparable between those included in the analysis and those with missing information on 28-day vital status, suggesting that outcomes were also likely comparable between these groups (Supplemental Table 7). Results from the analysis of the multiple imputed dataset were similar to the overall results (Supplemental Table 8).

Table 4.

Association of ACEi/ARB discontinuation with 28-day mortality in ACEi/ARB users

| Model | Recipients of Kidney Transplant (n=160) | Patients on Dialysis (n=188) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuers | Discontinuers | P Value | Continuers | Discontinuers | P Value | |

| Event rate (events)a | 5.8 (55) | 4.9 (33) | 7.2 (184) | 6.0 (60) | ||

| Model 1b | Reference | 3.05 (1.40 to 6.62) | 0.005 | Reference | 1.16 (0.64 to 2.08) | 0.63 |

| Model 2c | Reference | 4.48 (1.87 to 10.71) | 0.001 | Reference | 1.41 (0.69 to 2.88) | 0.34 |

| Model 3d | Reference | 5.23 (1.99 to 13.73) | 0.001 | Reference | 1.68 (0.77 to 3.66) | 0.19 |

| Model 4e | Reference | 5.03 (1.84 to 13.76) | 0.002 | Reference | 2.01 (0.91 to 4.45) | 0.09 |

| Model 5f | Reference | 1.36 (0.40 to 4.58) | 0.62 | Reference | 1.52 (0.51 to 4.56) | 0.45 |

Presented are the hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) in transplant recipients and patients on dialysis, separately, unless otherwise indicated. ACEi/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker.

Event rate per 100 person-weeks.

Model 1, crude.

Model 2, model 1 plus age, sex, and frailty.

Model 3, model 2 plus systolic BP, diabetes, and heart failure.

Model 4, model 3 plus start of anti-inflammatory therapy and antiviral therapy.

Model 5, model 4 plus cough, shortness of breath, fever, pulse rate, respiration rate, lymphocyte count, C-reactive protein, and >25% serum creatinine increase (only in transplant population).

Discussion

Among patients on dialysis and kidney transplant recipients diagnosed with COVID-19, we found no significant association between prior ACEi/ARB use or ACEi/ARB continuation and 28-day mortality after adjusting for baseline demographics, comorbidities, and the severity of COVID-19. There was also no substantially higher risk for secondary outcomes, including the incidence of hospital admission, ICU admission, or mechanical ventilator support. Although unadjusted analyses suggested that ACEi/ARB discontinuation in kidney transplant recipients was associated with worse mortality rates, as expected, this association effect was lost after adjusting for severity of COVID-19.

ACE2 is a carboxypeptidase homolog of ACE, discovered in 2000, that promotes the degradation of angiotensin II (Ang II; vasoconstrictor effects) to Ang 1–7 (vasodilatory effects), and Ang I to Ang 1–9 (11). ACE2 expression was initially thought to be restricted to the testis, kidney, and heart, but later studies demonstrated widespread ACE2 distribution in the lung, liver, small intestine, brain, and placenta, among others (12). Whereas ACE is highly expressed in the lungs, ACE2 is abundantly expressed in the kidneys. Within the kidney, ACE2 has explicitly been found in the apical membranes of the proximal tubules and in the glomerular epithelial cells (podocytes) (13). Coronaviruses use ACE2 as a receptor to enter type II pneumocytes or alveolar epithelial type II; therefore, the presence of ACE2 protein in lungs is important for virus cell entry (4). Preliminary studies during the past 2 decades suggest that RAS blockade upregulates ACE2 expression in different organs and tissues (1,2); however, its effect on lungs, mainly in type II pneumocytes, had not been assessed. Reviewing this knowledge in an editorial, Fang et al. (6) hypothesized that, in theory, patients with chronic disease (such as diabetes and hypertension) treated with ACE2-increasing drugs might be at a higher risk for severe COVID-19, and suggested that calcium channel blockers may be a suitable alternative treatment in these patients. The publication of this hypothesis in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine created unrest and led to suggestions that RAS blockade should be stopped, not only as part of COVID-19 treatment protocols, but in all high-risk patients, to minimize problems when being infected. However, the advantages of such an approach should be weighed against the effect that the withdrawal of RAS blockade could have on patients not infected with COVID-19, but who have, for instance, CKD. In such patients, RAS blockade has proven efficacious in preventing difficult clinical outcomes, including hospital admissions, kidney failure, and death. Therefore, several research groups and societies advised to continue RAS blockade, pending evidence to support or refute Fang et al.’s hypothesis (14).

Several studies, including the ERACODA cohort, have demonstrated that the mortality rate in patients with kidney failure, either in patients on dialysis or in kidney transplant recipients, is high (10,15–17). A study using the OpenSAFELY health analytics platform, which includes data of >17 million people in the United Kingdom (among whom almost 11,000 died from COVID-19), suggested that patients on dialysis and transplant recipients are at an even higher risk than those with other known risk factors, including chronic heart and lung disease (8,18). Given that kidney failure reduces life expectancy after contracting COVID-19, it is crucial to ascertain whether ACEi/ARB use or continuation worsens the mortality associated with COVID-19 in this specific population.

To date, several observational cohort studies have focused on the effect of RAS blockade on the severity of COVID-19 (13–17). However, to our knowledge, none of these studies mention the effect of RAS blockade specifically in patients with kidney failure (treated with dialysis or a kidney transplant). A recent analysis of 12,500 patients tested for COVID-19 showed no association of previous treatment with RAS blockade with a higher risk of testing positive for COVID-19 (19). There was also no association between RAS blockade treatment and the severity of COVID-19. Similarly, another study found no association of RAS blockade with the risk of COVID-19 or the severity of the disease (20). Our study extends this knowledge by demonstrating that RAS blockade is also not associated with survival in patients with kidney failure and COVID-19.

In another study of 681 patients with hypertension and confirmed or clinically suspected COVID-19 (21), ARB treatment was not associated with mortality, severity, or other in-hospital complications. Interestingly, this study also assessed the association of ARB discontinuation with mortality and severity of COVID-19. Surprisingly, and in contrast to expectations, ARB discontinuation was associated with a higher risk of mortality, invasive ventilation, and AKI (20,21). Similarly, in our study, RAS discontinuation was associated with higher 28-day mortality in kidney transplant recipients. However, after adjusting for the severity of the disease, this effect was lost. On the basis of these findings, we suggest that disease severity could be, at least in part, responsible for discontinuation of ACEi/ARB use and is, therefore, likely accountable for the excess risk of mortality in those who discontinue ACEis/ARBs. One might speculate that patients with severe disease at admission, who are more likely to develop shock and AKI, will be those whose RAS blockade would be withdrawn.

Our study is observational which, by definition, is a limitation. In addition, some patients in our study may not have been on RAS blockade because of intolerance, such as electrolyte derangement or preexisting low BP, and this could not be considered for further analysis. RCTs are needed to ascertain the real effect of RAS blockade on COVID-19 risk and severity. After the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, several RCTs have been initiated, including the Angiotensin Receptor Blockers and Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Adverse Outcomes in Patients With COVID19 (BRACE-CORONA) study, ACE Inhibitors or ARBs Discontinuation in Context of COVID-19 Pandemic (ACORES-2), Randomized Elimination and Prolongation of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in coronavirus 2019 (REPLACE COVID), Effects of Discontinuing Renin-angiotensin System Inhibitors in Patients With COVID-19 (RASCOVID-19), and Stopping ACE-inhibitors in COVID-19 (ACEi-COVID) (7,22–26). However, none have focused on patients with kidney failure. The first study with public results, the BRACE-CORONA study, examined continuing versus discontinuing ACEi/ARB in patients on these medications who were hospitalized with COVID-19 (27). The results, recently presented at the European Society of Cardiology Congress, show that, among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and receiving chronic ACEis/ARBs, discontinuing ACEis/ARBs was neither beneficial nor deleterious with regard to mortality or length of hospitalization (27). In concordance, the REPLACE COVID study, which examined continuation versus discontinuation of ACEi/ARB therapy among patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19, demonstrated no differences in the severity of the COVID-19 course in terms of length of hospital stay, need for intensive care, invasive mechanical ventilation, or death (24). Our results specifically in patients with kidney failure extend these data.

In this observational cohort study, which includes a large number of patients on dialysis and kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19, previous use of ACEis/ARBs was not associated with a higher risk of 28-day mortality. Furthermore, the discontinuation of ACEis/ARBs was not linked with risk of death in kidney transplant recipients and patients on dialysis with COVID-19. In the COVID-19 pandemic era, our study suggests that RAS blockade in patients with kidney failure can be continued. Routine withdrawal of RAS blockade in patients with kidney failure, who are at risk of cardiovascular and kidney events, will confer significantly more harm.

Disclosures

C. Basile reports serving on the editorial boards of Journal of Nephrology and Nephology Dialysis Transplantation. A. Covic reports and serving as a member of the EUDIAL Working Group of the ERA-EDTA, on the editorial board of International Urology and Nephrology, and as president of the Romanian Society of Nephrology; and having consultancy agreements with, and receiving honoraria from, Fresenius Medical Care. M. Crespo reports receiving speaker honoraria from Astellas, Chiesi, and Novartis; serving on the Board of the Descartes Group of EDTA and as coordinator of the Transplant Group of the Spanish Society of Nephrology; and being employed by Hospital del Mar. G. de Arriba reports being employed by University Hospital Guadalajara. R. Duivenvoorden reports being employed by Radboudumc. R.T. Gansevoort reports serving as a scientific advisor for, or member of, American Journal of Kidney Diseases, CJASN, Journal of Nephrology, Kidney360, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, and Nephron Clinical Practice; having consultancy agreements with, and receiving research funding from, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Galapagos, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Sanofi-Genzyme; receiving honoraria from Bayer, Galapagos, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi-Genzyme; and being employment by University Medical Center Groningen. Z.A. Massy reports being employed by Ambroise Paré University Hospital (University of Paris Ouest); receiving research funding from Amgen, Baxter, Fresenius Medical Care, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Merck Sharp and Dohme-Chibret, Otsuka, and Sanofi-Genzyme; receiving honoraria or fees for travel from Astellas, Baxter, and Sanofi-Genzyme; receiving government support for the CKD-REIN project and experimental projects; and serving as a scientific advisor for, or member of, Journal of Nephrology, Journal of Renal Nutrition, Kidney International, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, and Toxins. M. Noordzij reports being employed by the Department of Internal Medicine, University Medical Center Groningen. A. Ortiz reports receiving honoraria and fees for speaker engagements from Advicienne, Alexion, Amgen, Amicus, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Freeline, Fresenius Medical Care, Genzyme, Kyowa Kirin, Menarini, Mundipharma, OM Pharma, Otsuka, Shire, and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma; receiving research funding from AstraZeneca, Mundipharma, and Sanofi-Genzyme; serving as the editor-in-chief of Clinical Kidney Journal, and on the editorial boards of Journal of Nephrology, JASN, and Peritoneal Dialysis International; serving on the Dutch Kidney Foundation Scientific Advisory Board, on the ERA-EDTA Council, and on the board of directors for Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria–Fundación Jiménez Díaz Autonomous University of Madrid; being employed by Fundación Jiménez Díaz Autonomous University of Madrid; having consultancy agreements with Retrophin and Sanofi-Genzyme; and serving as a scientific advisor for, or member of, the Spanish Society of Nephrology. E. Petridou reports serving as vice president of European Kidney Patients’ Federation; serving on a speakers bureau for European Kidney Health Alliance and European Kidney Patients’ Federation; and being employed by Pancyprian Kidney Organization. M. J. Soler reports receiving research funding from Abbvie and Boehringer Ingelheim; receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esteve, FMC, Jansen, Mundipharma, Novonordisk, and Otsuka; having consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Esteve, Jansen, Mundipharma, and Novonordisk; serving as a scientific advisor for, or member of, BMC Nephrology and Clinical Kidney Journal; serving as a council member of, and on the scientific advisory board for, ERA-EDTA; being employed by Hospital del Vall d’Hebron; and having other interests/relationships with Sociedad Catalana de Nefrologia and Sociedad Española de Nefrología (as a member). K. Stevens reports serving as an ERA-EDTA Council Member and being employed by National Health Service Greater Glasgow and Clyde. P. Vart reports serving as an associate editor for BMC Public Health and being employed by Radboud University. C. White reports having other interests/relationships with European Kidney Health Alliance, European Kidney Patients’ Federation, ERA, European Society for Organ Transplantation, European Transplant and Dialysis Sports Federation, and World Transplant Games Federation and being employed by the Irish Kidney Association. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by ERA-EDTA, Nierstichting (Dutch Kidney Foundation), Baxter, and Sandoz unrestricted research grants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all people who entered information in the ERACODA database for their participation, and especially all health care workers who have taken care of the included COVID-19 patients.

The funding organizations had no role in the design of the study, interpretation of results, or in writing of the manuscript.

All authors contributed to data collection, study design, data analysis, interpretation, and drafting of this paper.

The ERACODA Collaboration is an initiative to study prognosis and risk factors for mortality due to COVID-19 in patients with a kidney transplant or on dialysis that is endorsed by the ERA-EDTA. ERACODA is an acronym for the ERA COVID-19 Database. The organizational structure contains a working group, assisted by a management team and an advisory board. The ERACODA Working Group members are C.F.M. Franssen, R.T. Gansevoort (coordinator), M.H. Hemmelder, L. B. Hilbrands, and K.J. Jager; the ERACODA Management Team members are R. Duivenvoorden, M. Noordzij, and P. Vart; the ERACODA Advisory Board members are D. Abramowicz, C. Basile, A. Covic, M. Crespo, Z.A. Massy, S. Mitra, E. Petridou, J.E. Sanchez, and C. White.

Data Sharing Statement

Collaborators who entered data in ERACODA remain the owners of these data. Therefore, the database cannot be disclosed to any third party without the prior written consent of all data providers. Research proposals can be submitted to the working group via COVID.19.KRT@umcg.nl. If deemed of interest and methodologically sound by the working group and advisory board, the analyses needed for the proposal will be carried out by the management team.

Footnotes

The list of nonauthor contributors is extensive and has been provided in the Supplemental Summary 1.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Shining More Light on RAS Inhibition during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” on pages 1002–1004.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.18961220/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplementary Summary 1. Affiliations and names of collaborative authors.

Supplemental Table 1. Distribution of 28-day mortality, hospitalization, ICU admission, and ventilator support in ACEi/ARB users and non-users in transplant and dialysis patients (presented are proportions with 95% confidence interval).

Supplemental Table 2. Association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality with primary and secondary outcomes in model 5.

Supplemental Table 3. Association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality (only PCR positive cases).

Supplemental Table 4. Association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality (hospitalized patients only).

Supplemental Table 5. Characteristics of kidney transplant and dialysis patients with COVID-19, overall and according to ACEi/ARB use status (continue/discontinue).

Supplemental Table 6. Baseline characteristics by missingness status.

Supplemental Table 7. Baseline characteristics by 28-day mortality missingness status.

Supplemental Table 8. Association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality in multiple imputed dataset.

Supplemental Figure 1. Flow chart of study participants selection.

Supplemental Figure 2. Test of proportionality in 28-day mortality analysis for (A) ACEi/ARB users versus nonusers in transplant patients (B) ACEi/ARB users versus nonusers in dialysis patients.

Supplemental Figure 3. Cumulative hospitalization incidence in: (A) transplant patients and (B) dialysis patients by ACEi/ARB use.

Supplemental Figure 4. Cumulative ICU admission incidence in: (A) transplant patients and (B) dialysis patients by ACEi/ARB use.

Supplemental Figure 5. Cumulative ventilator support incidence in: (A) transplant patients and (B) dialysis patients by ACEi/ARB use.

Supplemental Figure 6. Association of ACEi/ARB use with 28-day mortality across subgroups of age (<65 years/≥65 years), sex (female/male), obesity (no/yes), hypertension (no/yes), diabetes (no/yes), heart failure (no/yes) in: (A) transplant patients and (B) dialysis patients.

References

- 1.Soler MJ, Barrios C, Oliva R, Batlle D: Pharmacologic modulation of ACE2 expression. Curr Hypertens Rep 10: 410–414, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soler MJ, Ye M, Wysocki J, William J, Lloveras J, Batlle D: Localization of ACE2 in the renal vasculature: Amplification by angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade using telmisartan. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F398–F405, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anguiano L, Riera M, Pascual J, Valdivielso JM, Barrios C, Betriu A, Mojal S, Fernández E, Soler MJ; NEFRONA study: Circulating angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity in patients with chronic kidney disease without previous history of cardiovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 1176–1185, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, Chen HD, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang RD, Liu MQ, Chen Y, Shen XR, Wang X, Zheng XS, Zhao K, Chen QJ, Deng F, Liu LL, Yan B, Zhan FX, Wang YY, Xiao GF, Shi ZL: A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579: 270–273, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noordzij M, Duivenvoorden R, Pena MJ, de Vries H, Kieneker LM; Collaborative ERACODA Authors: ERACODA: The European database collecting clinical information of patients on kidney replacement therapy with COVID-19. Nephrol Dial Transplant 35: 2023–2025, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M: Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 8: e21, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sparks MA, South A, Welling P, Luther JM, Cohen J, Byrd JB, Burrell LM, Batlle D, Tomlinson L, Bhalla V, Rheault MN, Soler MJ, Swaminathan S, Hiremath S: Sound science before quick judgement regarding RAS blockade in COVID-19. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 714–716, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gansevoort RT, Hilbrands LB: CKD is a key risk factor for COVID-19 mortality. Nat Rev Nephrol 26: 1–2, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortiz A, Cozzolino M, Fliser D, Fouque D, Goumenos D, Massy ZA, Rosenkranz AR, Rychlık I, Soler MJ, Stevens K, Torra R, Tuglular S, Wanner C, Gansevoort RT, Duivenvoorden R, Franssen CFM, Hemmelder MH, Hilbrands LB, Jager KJ, Noordzij M, Vart P, Gansevoort RT; ERA-EDTA Council; ERACODA Working Group: Chronic kidney disease is a key risk factor for severe COVID-19: A call to action by the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 36: 87–94, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilbrands LB, Duivenvoorden R, Vart P, Franssen CFM, Hemmelder MH, Jager KJ, Kieneker LM, Noordzij M, Pena MJ, de Vries H, Arroyo D, Covic A, Crespo M, Goffin E, Islam M, Massy ZA, Montero N, Oliveira JP, Muñoz AR, Sanchez JE, Sridharan S, Winzeler R, Gansevoort RT; ERACODA Collaborators: COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and dialysis patients: Results of the ERACODA collaboration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 35: 1973–1983, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY, Yagil C, Kozieradzki I, Scanga SE, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, da Costa J, Zhang L, Pei Y, Scholey J, Ferrario CM, Manoukian AS, Chappell MC, Backx PH, Yagil Y, Penninger JM: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature 417: 822–828, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soler MJ, Wysocki J, Batlle D: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and the kidney. Exp Physiol 93: 549–556, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye M, Wysocki J, William J, Soler MJ, Cokic I, Batlle D: Glomerular localization and expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-converting enzyme: Implications for albuminuria in diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3067–3075, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparks MA, Hiremath S, South A, Welling P, Luther M, Cohen J, Byrd B, Burrell LM, Batlle D, Tomlinson L, Bhalla V, Soler MJ, Swaminathan S, Pettit A, Moslehi J, Bress A, Turgeon R: The coronavirus conundrum: ACE2 and hypertension edition, 2020. Available at: http://www.nephjc.com/news/covidace2. Accessed: April 17, 2021

- 15.Goicoechea M, Sánchez Cámara LA, Macías N, Muñoz de Morales A, Rojas ÁG, Bascuñana A, Arroyo D, Vega A, Abad S, Verde E, García Prieto AM, Verdalles Ú, Barbieri D, Delgado AF, Carbayo J, Mijaylova A, Acosta A, Melero R, Tejedor A, Benitez PR, Pérez de José A, Rodriguez Ferrero ML, Anaya F, Rengel M, Barraca D, Luño J, Aragoncillo I: COVID-19: Clinical course and outcomes of 36 hemodialysis patients in Spain. Kidney Int 98: 27–34, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sánchez-Álvarez JE, Pérez Fontán M, Jiménez Martín C, Blasco Pelícano M, Cabezas Reina CJ, Sevillano Prieto ÁM, Melilli E, Crespo Barrios M, Macía Heras M, del Pino y Pino MD: Situación de la infección por SARS-CoV-2 en pacientes en tratamiento renal sustitutivo. Informe del Registro COVID-19 de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología (SEN). Nefrologia 40: 272–278, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jager KJ, Kramer A, Chesnaye NC, Couchoud C, Sánchez-Álvarez JE, Garneata L, Collart F, Hemmelder MH, Ambühl P, Kerschbaum J, Legeai C, Del Pino Y Pino MD, Mircescu G, Mazzoleni L, Hoekstra T, Winzeler R, Mayer G, Stel VS, Wanner C, Zoccali C, Massy ZA: Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int 98: 1540–1548, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, Curtis HJ, Mehrkar A, Evans D, Inglesby P, Cockburn J, McDonald HI, MacKenna B, Tomlinson L, Douglas IJ, Rentsch CT, Mathur R, Wong AYS, Grieve R, Harrison D, Forbes H, Schultze A, Croker R, Parry J, Hester F, Harper S, Perera R, Evans SJW, Smeeth L, Goldacre B: Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSafely. Nature 584: 430–436, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C, Troxel AB, Iturrate E, Johnson SB, Hausvater A, Newman JD, Berger JS, Bangalore S, Katz SD, Fishman GI, Kunichoff D, Chen Y, Ogedegbe G, Hochman JS: Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of COVID-19. N Engl J Med 382: 2441–2448, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M, Apolone G, Corrao G: Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockers and the risk of COVID-19. N Engl J Med 382: 2431–2440, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soleimani A, Kazemian S, Karbalai Saleh S, Aminorroaya A, Shajari Z, Hadadi A, Talebpour M, Sadeghian H, Payandemehr P, Sotoodehnia M, Bahreini M, Najmeddin F, Heidarzadeh A, Zivari E, Ashraf H: Effects of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) on in-hospital outcomes of patients with hypertension and confirmed or clinically suspected COVID-19. Am J Hypertens 33: 1102–1111, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel AB, Verma A: Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors impact on COVID-19 mortality: What’s next for ACE2? Clin Infect Dis 71: 2129–2131, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancia G: COVID-19, hypertension, and RAAS blockers: The BRACE-CORONA trial. Cardiovasc Res 116: E198–E199, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen JB, Hanff TC, William P, Sweitzer N, Rosado-Santander NR, Medina C, Rodriguez-Mori JE, Renna N, Chang TI, Corrales-Medina V, Andrade-Villanueva JF, Barbagelata A, Cristodulo-Cortez R, Díaz-Cucho OA, Spaak J, Alfonso CE, Valdivia-Vega R, Villavicencio-Carranza M, Ayala-García RJ, Castro-Callirgos CA, González-Hernández LA, Bernales-Salas EF, Coacalla-Guerra JC, Salinas-Herrera CD, Nicolosi L, Basconcel M, Byrd JB, Sharkoski T, Bendezú-Huasasquiche LE, Chittams J, Edmonston DL, Vasquez CR, Chirinos JA: Continuation versus discontinuation of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: A prospective, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med 9: 275–284, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen JB, Hanff TC, Corrales-Medina V, William P, Renna N, Rosado-Santander NR, Rodriguez-Mori JE, Spaak J, Andrade-Villanueva J, Chang TI, Barbagelata A, Alfonso CE, Bernales-Salas E, Coacalla J, Castro-Callirgos CA, Tupayachi-Venero KE, Medina C, Valdivia R, Villavicencio M, Vasquez CR, Harhay MO, Chittams J, Sharkoski T, Byrd JB, Edmonston DL, Sweitzer N, Chirinos JA: Randomized elimination and prolongation of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in coronavirus 2019 (REPLACE COVID) trial protocol. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 22: 1780–1788, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jia X, Al Rifai M, Hussain A, Martin S, Agarwala A, Virani SS: Highlights from studies in cardiovascular disease prevention presented at the digital 2020 European Society of Cardiology Congress: Prevention is alive and well. Curr Atheroscler Rep 22: 72, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopes RD: Continuing versus suspending angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers - BRACE CORONA, 2020. American College of Cardiology. Available at: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/clinical-trials/2020/08/29/13/05/brace-corona. Accessed October 7, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.