Abstract

Objectives

It has been suggested that pregnant women were affected more severely during the late wave, as opposed to the early wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The aim of our study was to compare the proportion of pregnant women among hospitalized women of childbearing age, their rate of intensive care (ICU) admission, need for mechanical ventilation and mortality during the waves.

Methods

The study is a retrospective analysis of claims data on women of childbearing age (16–49 years) admitted to 76 hospitals with a laboratory-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. The observation period was divided into first wave (7 March 2020 to 30 September 2020) and second wave (1 October to 17 April 2021). Co-morbidities derived from claims data were summarized in the Elixhauser Co-morbidity Index (ECI).

Results

A total of 1879 women were included, 532 of whom were pregnant. During the second wave, the proportion of pregnant women was higher (29.3% (484/1650) versus 21.0% (48/229), p < 0.01). They were older (mean ± SD 29.1 ± 5.9 years versus 27 ± 6.3 years, p 0.02 in the first wave) and had comparable co-morbidities (ECI mean ± SD 0.3 ± 3.5 versus –0.2 ± 2.0, p 0.30). Of the pregnant women, 6.2% (3/48) were admitted to ICU during the first wave versus 3.3% (16/484) during the second wave (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.14–1.83, p 0.30), 2.1% (1/48) were ventilated versus 1.2% (6/484, OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.07–5.23, p 0.64). No deaths were observed among the hospitalized pregnant women in either wave.

Conclusions

Proportionally more pregnant women with COVID-19 were hospitalized in the second wave compared with the first wave but no more severe outcomes were registered.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, Intensive care unit, Mortality, Pregnant women, Second wave

Introduction

From the first appearance of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) there were concerns that infection might affect pregnant women more severely with a high risk of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death [1]. During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic few pregnant women were infected. This changed during the second wave when infection rates increased, especially in Europe. Some recent studies reported that proportionally more pregnant women with COVID-19 were hospitalized [2] or referred for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [3].

The aim of our study was to compare pregnant women with COVID-19 as a proportion of all women of childbearing age hospitalized with COVID-19 during the different waves, their rates of intensive care (ICU) admission, mechanical ventilation and mortality.

Materials and methods

The research was conducted as an observational retrospective cohort study. We included all women of childbearing age (16–49 years) admitted to 76 hospitals of the Helios Group between 7 March 2020 and 17 April 2021. Helios is the largest German hospital group. The proportion of basic to tertiary care is representative for the overall distribution of hospitals in Germany. Also, the patient mix is representative, because all Helios hospitals are fully covered by all health-care insurance plans. All eligible patients had a laboratory-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection (International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10) code U07.1). From April 2020, all patients were tested on hospital admission for SARS-CoV-2 and consequently ICD codes were recorded. For the pregnancy cohort, we included all pregnant women according to ICD diagnosis (O00–O99, Z.33–Z.39). Information on age, ICU, mechanical ventilation (invasive and non-invasive) and co-morbidities was retrieved from claims data. In Germany, the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic took place in March/April 2020. During the summer months both the infection rates and hospitalizations decreased sharply. The second wave started in September 2020 and the third in February 2021 largely overlapping without any interval phase like in summer 2020. For our analysis, we therefore defined 1 October 2020 as the cut-off between first and second wave and summarized data from the second and third waves. Claims data on co-morbidities were summarized in the Elixhauser Co-morbidity Index (ECI) [4].

Statistical analysis

Inferential statistics were based on generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) specifying hospitals as random factor [5]. We employed Poisson GLMMs for count data. Effects were estimated with the lme4 package [6] in R (version 4.0.2). In all models, we specified varying intercepts for the random factor. For the comparison of treatments and outcomes, we used logistic GLMMs. For all tests, we applied a two-tailed 5% error criterion for significance.

For description of characteristics of cohort patients, we employed χ2 tests for binary variables and analysis of variance for numeric variables. For weighted ECI, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality algorithm was applied [7].

Ethics

The local echics Committee (vote: AZ490/20-ek) and Helios Kliniken GmbH data protection authority approved data use for this study.

Results

A total of 1879 women of childbearing age were hospitalized and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, 532 (28.3%) of whom were pregnant. Pregnant women were significantly younger (mean ± SD: 28.9 ± 5.9 years versus 37.3 ± 9.3 years, p ≤ 0.01) and had significantly fewer co-morbidities than non-pregnant women (ECI = 0.2 versus 3.0, p < 0.01), including pregnancy-associated obesity (5.8% (31/532) versus 14.8% (199/1347), p < 0.01) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Comparison of patient cohorts, included were all diagnoses with at least one case in each group (non-pregnant versus pregnant)

| No pregnancy |

Pregnancy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion (n) |

Proportion (n) |

|||||

| First wave |

Second wave |

P Value |

First wave |

Second wave |

P Value |

|

| n = 181 | n = 1166 | n = 48 | n = 484 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 37.3 ± 9.4 | 37.3 ± 9.3 | 0.96 | 27.0 ± 6.3 | 29.1 ± 5.9 | 0.02 |

| ≤17 years | 2.8% (5) | 2.7% (31) | 1.00 | 2.1% (1) | 1.2% (6) | 1.00 |

| 18–29 years | 22.1% (40) | 19.6% (228) | 0.49 | 62.5% (30) | 53.1% (257) | 0.27 |

| 30–39 years | 25.4% (46) | 28.0% (326) | 0.53 | 33.3% (16) | 41.7% (202) | 0.33 |

| 40–49 years | 49.7% (90) | 49.8% (581) | 1.00 | 2.1% (1) | 3.9% (19) | 0.81 |

| Elixhauser co-morbidity index | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.4 ± 5.7 | 3.1 ± 7.1 | 0.21 | -0.2 ± 2.0 | 0.3 ± 3.5 | 0.30 |

| <0 | 17.1% (31) | 18.4% (215) | 0.75 | 18.8% (9) | 16.3% (79) | 0.82 |

| 0 | 50.3% (91) | 45.5% (530) | 0.26 | 79.2% (38) | 75.4% (365) | 0.69 |

| 1–4 | 6.1% (11) | 6.2% (72) | 1.00 | 0.0% (0) | 1.4% (7) | 0.86 |

| 5 | 26.5% (48) | 29.9% (349) | 0.40 | 2.1% (1) | 6.8% (33) | 0.33 |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||

| yes | 1.7% (3) | 2.1% (24) | 0.94 | 0.0% (0) | 0.2% (1) | 1.00 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | ||||||

| yes | 1.7% (3) | 3.9% (45) | 0.20 | 0.0% (0) | 0.4% (2) | 1.00 |

| Valvular disease | ||||||

| yes | 0.0% (0) | 0.7% (8) | 0.55 | 0.0% (0) | 0.2% (1) | 1.00 |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | ||||||

| yes | 11.6% (21) | 14.8% (173) | 0.30 | 2.1% (1) | 0.6% (3) | 0.81 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | ||||||

| yes | 9.4% (17) | 8.0% (93) | 0.62 | 0.0% (0) | 0.6% (3) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | ||||||

| yes | 6.1% (11) | 7.6% (89) | 0.55 | 6.2% (3) | 5.6% (27) | 1.00 |

| Hypothyroidism | ||||||

| yes | 7.2% (13) | 12.8% (149) | 0.04 | 2.1% (1) | 3.5% (17) | 0.92 |

| Liver disease | ||||||

| yes | 0.0% (0) | 3.2% (37) | 0.03 | 0.0% (0) | 0.8% (4) | 1.00 |

| Solid tumour without metastasis | ||||||

| yes | 1.7% (3) | 2.0% (23) | 1.00 | 0.0% (0) | 0.4% (2) | 1.00 |

| Coagulopathy | ||||||

| yes | 1.1% (2) | 1.9% (22) | 0.66 | 0.0% (0) | 2.7% (13) | 0.51 |

| Obesity | ||||||

| yes | 13.8% (25) | 14.9% (174) | 0.78 | 2.1% (1) | 6.2% (30) | 0.40 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | ||||||

| yes | 19.3% (35) | 21.9% (255) | 0.50 | 2.1% (1) | 4.3% (21) | 0.71 |

| Blood loss anaemia | ||||||

| yes | 0.0% (0) | 0.4% (5) | 0.82 | 0.0% (0) | 0.2% (1) | 1.00 |

| Deficiency anaemia | ||||||

| yes | 3.3% (6) | 2.1% (24) | 0.43 | 16.7% (8) | 11.4% (55) | 0.40 |

| Drug abuse | ||||||

| yes | 0.0% (0) | 0.3% (3) | 1.00 | 0.0% (0) | 0.2% (1) | 1.00 |

| Depression | ||||||

| yes | 2.8% (5) | 5.5% (64) | 0.17 | 0.0% (0) | 0.2% (1) | 1.00 |

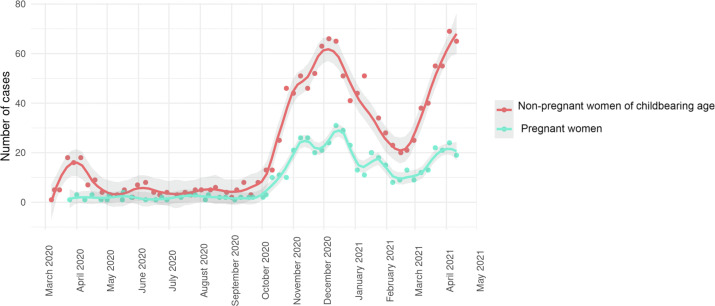

We saw an expected rise in total number of SARS-CoV-2-positive women admitted to the hospital in the second wave, concordant with higher infection rates in the general population (Fig. 1 ). Furthermore, we observed a rise of the proportion of pregnant women (first wave 21.0% (48/229) versus second wave 29.3% (484/1650), crude risk ratio interaction 1.57, 95% CI 1.12–2.18, p < 0.01). Pregnant women were younger in the first wave (mean ± SD 27 ± 6.3 years versus 29.1 ± 5.9 years, p 0.02) than in the second, with comparable co-morbidities (ECI mean ± SD –0.2 ± 2.0 versus 0.3 ± 3.5, p 0.30). For non-pregnant women, no difference in age and co-morbidities was observed. Of 48 pregnant women, three (6.2%) were admitted to ICU during the first wave versus 16/484 in the second wave (3.3%, OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.14–1.83, p 0.30). One out of 48 (2.1%) was mechanically ventilated in the first wave versus 6/484 in the second wave (1.2%, OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.07–5.23, p 0.64). The rate of caesarean section did not differ with 3/48 in the first wave (6.2%) and 25/484 in the second wave (5.2%, p 0.82). No deaths were observed among the hospitalized pregnant women in either wave (95% CI 0.00%–0.91%). The odds for non-pregnant women for ICU admission, ventilation and death did not change significantly between the waves (ICU OR 1.60, 95% CI 0.92–2.79, p 0.09; ventilation OR 1.65, 95% CI 0.80–3.37, p 0.17, death OR 3.25, 95% CI 0.43–24.49, p 0.25).

Fig. 1.

Weekly case numbers of pregnant and non-pregnant women of childbearing age with coronavirus disease 2019 admitted to hospitals. Dots represent weekly case numbers; lines are based on locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS).

Discussion

Our data show a significant increase in the proportion of pregnant women among all women of childbearing age hospitalized with a SARS-CoV-2 infection during the second wave in Germany. This result is in accordance with previous findings from Spain [2]. The reason for this increase is probably multifactorial. The German Federal Statistical Office reported that the birth rate between December 2020 and February 2021 remained comparable to previous years, indicating that the first wave had no impact on pregnancies [8]. However, in March 2021 the number of births rose by roughly 10% in comparison to March 2020, showing the highest number in over 20 years [9]. This indicates a rise in conceptions in the period between the two waves, leading to a higher rate of pregnant women in the second wave. This might have added to the higher proportion among hospitalized women with COVID-19. A further explanation could be the growing knowledge of more severe courses of infection in pregnancy. Especially during the second wave, reports emerged that indicated a higher risk for pregnant women, putting them in focus [10]. Hence, medical staff might have been more cautious and admitted pregnant women more frequently to the hospital for better monitoring.

We found no difference in the OR for ICU admission and mechanical ventilation between the two waves. In total, ICU and ventilation were rare among pregnant women, which does not allow further analyses. No COVID-19-related death among pregnant women was observed, whereas previous studies have shown mortality rates ranging from 0.8% to 1.6% [3,11,12]. A higher ICU admission rate of pregnant women during the British second wave was documented [13], without reporting whether this difference was statistically significant. Other research described a significant increase of pregnant women among all women of childbearing age referred for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [3]. These findings suggest a more severe course in the second wave, but it could also have been partially caused by an increase in the overall numbers of pregnancies as was observed in England and Wales [14].

A major limitation of our study is that we could not compare the outcome of infected pregnant women to non-pregnant women: to sufficiently control for biases (e.g. the admission with COVID-19 versus because of COVID-19) a matched pair analysis would be required, which was not possible with our data.

In conclusion, we observed an increased proportion of pregnant women among hospitalized women with COVID-19 that may be partially a result of the higher pregnancy rate in the whole population. Our data do not confirm the previous described trend that pregnant women experienced a worse outcome of COVID-19 infection during the second wave.

Transparency declaration

RK, AMH and CK declare that they own shares in Fresenius, all the other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. No external funding was received for the study.

Access to data

The medical data are stored in Leipzig Heart Center.

Authors' contribution

CK, MB and IN conceived the work, SH, AB, AMH, RK acquired the data; CK, SH and IN interpreted the data and performed the statistical analysis; CK, MB and IN wrote the manuscript; CK, MB, SH, AB, RK and IN critically revised the manuscript and CK, MB, SH, AB, RK and IN approved the version to be published.

Editor: L. Leibovici

References

- 1.Siston A.M., Rasmussen S.A., Honein M.A., Fry A.M., Seib K., Callaghan W.M., et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2010;303:1517–1525. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iftimie S., López-Azcona A.F., Vallverdú I., Hernández-Flix S., De Febrer G., Parra S., et al. First and second waves of coronavirus disease-19: a comparative study in hospitalized patients in Reus, Spain. PloS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadiwar S., Smith J.J., Ledot S., Johnson M., Bianchi P., Singh N., et al. Were pregnant women more affected by COVID-19 in the second wave of the pandemic? Lancet. 2021;397:1539–1540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00716-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Walraven C., Austin P.C., Jennings A., Quan H., Forster A.J. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009:626–633. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baayen R.H., Davidson D.J., Bates D.M. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J Mem Lang. 2008;59:390–412. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. arXiv preprint arXiv:14065823. 2014.

- 7.Moore B.J., White S., Washington R., Coenen N., Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data. Med Care. 2017;55:698–705. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Statistisches Bundesamt . 2021. No marked impact of the first lockdown on the number of births in Germany. Expected increase of 0.8% in the number of births from December 2020 to February 2021 is within the usual range of fluctuations.https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2021/03/PE21_149_126.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistisches Bundesamt . 2021. Births in March 2021: highest number in over 20 years.https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2021/06/PE21_280_126.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim C.N.H., Hutcheon J., van Schalkwyk J., Marquette G. Maternal outcome of pregnant women admitted to intensive care units for coronavirus disease 2019. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:773–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pineles B.L., Goodman K.E., Pineles L., O’Hara L.M., Nadimpalli G., Magder L.S., et al. In-hospital mortality in a cohort of hospitalized pregnant and nonpregnant patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1186–1188. doi: 10.7326/M21-0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villar J., Ariff S., Gunier R.B., Thiruvengadam R., Rauch S., Kholin A., et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:817–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Audit I. ICNARC report on COVID-19 in critical care. 2020;10:2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office for National Statistics . 2021. Provisional births in England and Wales: 2020 and quarter 1 (jan to mar)https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/articles/provisionalbirthsinenglandandwales/2020andquarter1jantomar2021 Available at: [Google Scholar]