Abstract

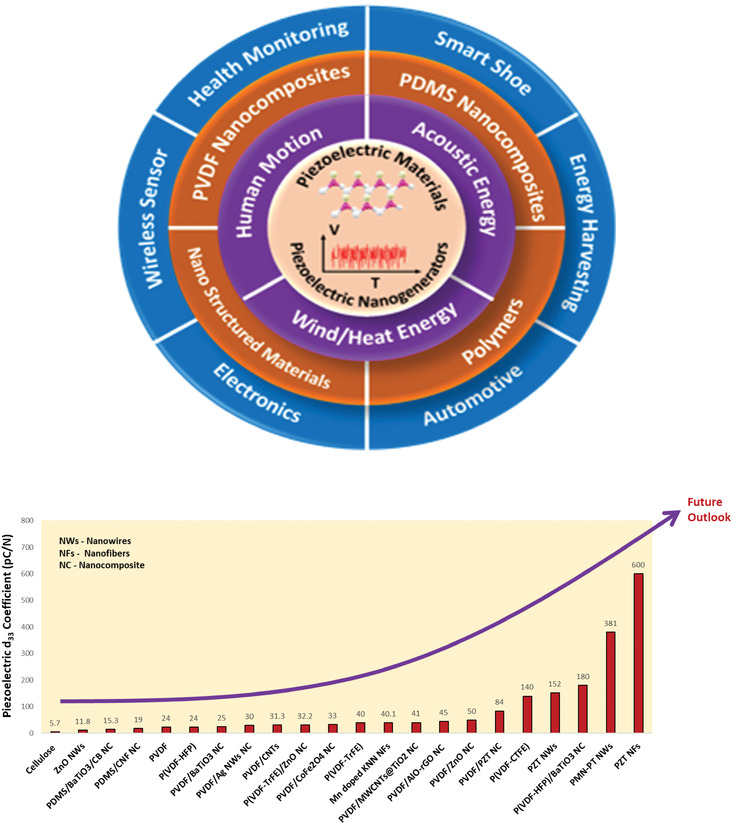

Piezoelectric materials are widely referred to as “smart” materials because they can transduce mechanical pressure acting on them to electrical signals and vice versa. They are extensively utilized in harvesting mechanical energy from vibrations, human motion, mechanical loads, etc., and converting them into electrical energy for low power devices. Piezoelectric transduction offers high scalability, simple device designs, and high‐power densities compared to electro‐magnetic/static and triboelectric transducers. This review aims to give a holistic overview of recent developments in piezoelectric nanostructured materials, polymers, polymer nanocomposites, and piezoelectric films for implementation in energy harvesting. The progress in fabrication techniques, morphology, piezoelectric properties, energy harvesting performance, and underpinning fundamental mechanisms for each class of materials, including polymer nanocomposites using conducting, non‐conducting, and hybrid fillers are discussed. The emergent application horizon of piezoelectric energy harvesters particularly for wireless devices and self‐powered sensors is highlighted, and the current challenges and future prospects are critically discussed.

Keywords: energy harvesting, flexible devices, nanostructured materials, piezoelectric nanogenerator, polymer nanocomposites, polyvinylidene fluoride copolymers

This paper presents a comprehensive review of the energy harvesting performance of different types of piezoelectric materials. These materials include nanostructured materials, polymers, polymer nanocomposites synthesized using different types of fillers and piezoelectric films. The fabrication techniques, energy harvesting mechanisms, and applications of piezoelectric nanogenerators built using these materials are discussed thoroughly.

1. Introduction

Anthropogenic environmental pollution and climate change‐related to energy production and consumption present a key challenge to humanity and our technological future. The development of renewable, environmentally friendly, and cost‐effective energy sources has increasingly become important to meet the energy demands of the future.[ 1 ] There are various renewable energy types present in our environment ranging from kinetic energy to solar energy and bioenergy, and extensive research has been conducted on energy harvesting technologies to scavenge energy from readily available sources like vibration, human motion, water, air, heat, light, chemical reactions into useful electrical energy for powering small scale devices.[ 2, 3, 4, 5 ] While there remain many challenges for such energy harvesting methods including variable and unpredictable ambient conditions, excellent progress in wireless communication, and low power integrated circuits (ICs) have decreased power consumption requirements and further attracted portable energy harvesting approaches.[ 2 ] For example, the power requirement of the latest generation of personal wireless communication devices is of the order of tens of mW.[ 6, 7 ] Advanced wireless technologies and microelectronics have facilitated the development of a new generation of wearable devices such as, body‐mounted sensors, fitness trackers, smart clothing, augmented reality sensors, etc. In addition, the concept of the Internet of Things (IoT) has led to placing smart equipment in remote areas such as, health care devices inside the human body, where it is difficult and sometimes impossible to charge batteries. Therefore, energy harvesting has become necessary to sustain such self‐powered systems.

Among ambient energy sources, low‐intensity kinetic energy from random displacements, human activities such as, finger tapping, running, walking, heartbeat, respiration; structural vibrations from manufacturing equipment and transportation vehicles; low Reynolds‐number flow of fluids like wind, water are abundantly available. Recent research has focused on kinetic energy harvesting based on three main transduction mechanisms: Electromagnetic, piezoelectric, and triboelectric. The advantages and disadvantages of these energy harvesting methods have been widely discussed in the literature,[ 8 ] with most studies focusing on piezoelectric transduction motivated by its superior power densities, high energy conversion efficiency, simpler architectures, and high scalability.[ 9, 10 ] As a result, applications of piezoelectric materials have increased tremendously across numerous fields including sensors,[ 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 ] actuators,[ 19, 20, 21 ] nanogenerators,[ 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 ] MEMS devices,[ 31, 32, 33 ] portable electronics,[ 34, 35 ] and biomedicine.[ 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 ]

Currently, the most widely used classes of piezoelectric materials range from lithium niobate (LiNbO3),[ 41 ] lead magnesium niobate‐lead titanate (PMN‐PT),[ 42 ] zinc oxide (ZnO),[ 43 ] lead zirconate titanate (PZT),[ 44, 45, 46 ] barium titanate (BaTiO3),[ 47 ] to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), and its copolymers.[ 25, 48, 49 ] Although lead (Pb) based ceramics such as, PZT exhibit high piezoelectric coefficients, their rigidity, brittleness, and toxicity limit their applications in flexible and stretchable devices.[ 13 ] Due to Pb toxicity, there is increasing concern about the use of PZT based devices in consumer products such as various smart systems, medical imaging devices, automobiles, and sound generators.[ 13 ] PZT based ceramics are also unsuitable for high‐temperature applications. On the contrary, Pb free ceramics such as, KNbO3, NaNbO3, etc., are biocompatible which allows their versatile utilization in sensors and actuators transplanted directly into living bodies. Additionally, their properties can be easily tailored which make them the best alternative in contrast to Pb based PZT ceramics. Polymers possess high flexibility, excellent stability, and biocompatibility, which makes them favorable for integration into flexible devices. The peak power density values of piezoelectric energy harvesters (PEHs) made using zinc oxide (ZnO) nanowires is up to 11 mW cm–3,[ 50 ] PZT nanowires up to 2.8 mW cm–3,[ 51 ] BaTiO3/P(VDF‐HFP) nanocomposites up to 0.48 Wcm–3.[ 52 ] For the complete list of power density values, readers can refer to Tables 1–3.

Table 1.

Summary of piezoelectric nanostructured materials for energy harvesting applications

| Nanostructured material | Length [L]/Diameter [D]/Thickness [T] of nanostructure | Synthesis method | Piezoelectric strain coefficient d33 [pC N–1] | Poling conditions | Applied load/pressure/strain%/load resistance | Output voltage [V] | Output current/current density | Power/power density | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D ZnO nanostructures | |||||||||

| ZnO nanowires | L = 0.2–0.5 µm | Vapor liquid‐solid process | – | No poling | 5 nN | (6–9) 10–3 | – | ≈10 pW µm–2 | [73, 74] |

| Phosphorus doped‐ ZnO nanowires |

D = 50 nm L = 600 nm |

Thermal vapor deposition | – | No poling | 90–120 nN | 0.05–0.09 | – | – | [80] |

| ZnO nanowires |

D = 100–800 nm L = 100–500 µm |

Thermal vapor deposition | – | No poling | From finger tapping and running hamster | 0.1–0.15 | ≈0.0005 | – | [81] |

| ZnO nanorods |

D = 100 nm L = 1.5–2 mm |

Aqueous solution using Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and HMTA | – | No poling | 0.9 kgf | – | ≈1 µA cm–2 | – | [84] |

| ZnO nanorods |

D = 100 nm L = 1.5–2 mm |

Aqueous solution using Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and HMTA | – | No poling | 0.9 kgf | – | 4.76 µA cm–2 | – | [85] |

| ZnO nanorods |

L ≈ 2 µm D < 100 nm |

Aqueous solution using Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and HMTA | – | No poling | Bending and rolling | – | 2 µA cm–2 | – | [86] |

| ZnO nanowires |

D = 150 nm L = 2 µm |

Aqueous solution using Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and HMTA | – | No poling | 0.12% strain | 10 | 0.6 µA | 10 mW cm–3 | [87] |

| ZnO nanowires | – | Hydrothermal process | – | No poling | – | 20 | 6 µA | 0.2 W cm–3 | [88] |

| ZnO nanowires | – | Hydrothermal process | – | No poling | Punching by human palm | 58 | 134 µA | 0.78 W cm–3 | [89] |

| ZnO nanowires | L = 30 µm | Vapor deposition | – | No poling | 0.11% strain | 2 | 50 nA | – | [90] |

| ZnO nanorods | Aspect ratio = 20:1 | Aqueous solution using Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and HMTA | – | No poling | 0.9 mN | 4 × 10–5 | 4 nA | 0.76 µW cm–2 | [91] |

| ZnO nanorods |

L = 2 µm D = 50–60 nm |

Aqueous solution using Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and HMTA | – | No poling | 50 g acceleration | 1.07 | 1.88 mA cm–2 | 434 µW cm–2 | [93] |

| ZnO nanowires |

D = 300 nm L = 4 µm |

Wet chemical method | – | No poling | 0.19% strain | 1.2 | 26 nA | ≈70 nW cm–2 | [94] |

| ZnO nanowires |

D = 200 nm L = 50 µm |

Physical vapor deposition | – | No poling | 0.1% strain | 2.03 | 107 nA | ≈11 mW cm–3 | [50] |

| ZnO nanowires & Au‐coated ZnO NWs |

D = 50–200 nm L = 3.5 µm |

Hydrothermal process | – | No poling | – | 0.001 | 5 pA | – | [95] |

| ZnO nanowires & Pd‐coated ZnO NWs | – | Hydrothermal process | – | No poling | – | 0.003 | 17 pA | – | [96] |

| ZnO nanorods | – | Hydrothermal process | – | No poling | – | 0.01 | 10 nA | – | [97] |

| ZnO nanowires |

D = 100 nm L = 1 µm |

Hydrothermal process | – | No poling | Sound waves at 100 dB, 100 Hz | 8 | 2.5 µA | – | [98] |

| ZnO nanorods |

D ≈ 150 nm L ≈ 1.5 µm |

Template‐free electrochemical deposition | 11.8 | No poling | 80 nN | 1.5 | 0.4 µA | – | [99] |

| 2D ZnO nanostructures | |||||||||

| ZnO nanosheets |

width ≈ 80 nm L ≈ 3 µm |

Aqueous solution using Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and HMTA | – | No poling | 4 kgf | ≈0.7 | ≈17 µA cm–2 | ≈11.8 µW cm–2 | [106] |

| Vanadium doped ZnO nanosheets |

Width = 900 nm–1.0 µm T = 15–20 nm |

Aqueous solution using Zn(NO3)2.6H2O, HMTA and V2O5 | 4 | No poling | 0.5 kgf | – | 1.0 µA cm–2 | – | [107] |

| ZnO nanowall and nanowall‐nanowire hybrid |

T = 200 nm, L = 2.4 µm T = 90 nm, L = 200 nm |

Chemical vapor deposition | – | No poling | 0.5 kgf | 0.002 | ≈500 nA cm–2 | – | [108] |

| ZnO nanowalls |

T = 60–80 nm L = 2–3 µm |

Hydrothermal process | – | No poling | Folding by human finger | 2.5 | 80 nA | 0.2 µW cm–2 | [109] |

| ZnO nanorods and nanowalls |

D = 42 ± 5 nm T ≈ 38 ± 28 nm, L ≈ 950 ± 370 nm |

Chemical bath deposition |

7.01 2.63 |

No poling | – | – | – | – | [110] |

| Nanostructures of other piezoelectric materials | |||||||||

| PZT nanofibers |

D ≈ 60 nm L ≈ 500 µm |

Electrospinning | 500‐600 | 4 V µm–1 above 140 °C for 24 h | 6 MΩ load resistance | 1.63 | – | 0.03 µW | [118] |

| PZT nanofibers | D = 370 nm | Electrospinning | – | 4 kV mm–1 at 130 °C for 15 min | 100 MΩ load resistance | 6 | 45 nA | 200 µW cm–3 | [119] |

| PZT nanowires | – | Electrospinning | – | 4 V µm–1 at 130 °C for 10 min | 100 MΩ load resistance | 3.2 | 50 nA | 170 µW cm–3 | [115] |

| PZT nanowires | L = 420 µm | Electrospinning | – | 5 kV mm–1 at 130 °C for 15 min | 0.53 MPa | 209 | 23.5 µAcm–2 | – | [120] |

| PZT nanowires |

D = 500 nm L = 5 µm |

Chemical epitaxial growth on Nb‐doped SrTiO3 substrate | 152 | 100 kV cm–1 in a dielectric fluid | Bending strain | 0.7 | 4 µAcm–2 | 2.8 mW cm–3 | [51] |

| ZnO nanowires/PZT heterojunction |

L ≈ 3 µm D = 50 nm |

Hydrothermal process and magnetron sputtering | – | Corona poling at 11 kV for 30 min | 0.9 kgf | – | 270 nA | – | [122] |

| PMN‐PT nanowires |

D = 400nm L = 200–800 nm |

Hydrothermal process | 381 | No poling | – | – | – | – | [123] |

| Mn doped (Na0.5K0.5)NbO3 (NKN) nanofibers | D ≈ 130 nm | Electrospinning under 13 kV | 40.06 | 60 kV cm–1 at 100 °C for 30 min | Bending strain | 0.3 | 50 nA | – | [124] |

| BaTiO3 nanowires |

D ≈ 90 nm L ≈ 1 µm |

Two‐step hydrothermal process | – | 120 kV cm–1 at RT for 24 h | 1 g RMS acceleration | 0.085 | ≈0.316 nA | 6.27 µW cm–3 | [126] |

| BaTiO3 nanowires |

D ≈ 600–630 nm L ≈ 45 µm |

Two‐step hydrothermal process | – |

≈75 kV cm–1 at RT for 12 h |

0.25 g RMS acceleration | 0.34 | – | – | [127] |

| 0.93(Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3‐0.07BaTiO3 nanofibers | – | Sol–gel electrospinning | 109 | – | Human finger | 30 | 80 nA | – | [128] |

| GaN nanowires |

L = 121 ± 37 nm D = 88 ± 21 nm |

Plasma‐assisted molecular beam epitaxy | – | No poling | 173 nN | 0.44 | – | – | [130] |

| GaN nanowires |

D = 45 ± 20 nm L = 1 µm ± 120 nm |

Plasma‐assisted molecular beam epitaxy | – | No poling | 1.5 N | 0.35 | – | ≈12.7 mW cm−3 | [131] |

Table 3.

Summary of piezoelectric polymer nanocomposites for energy harvesting applications

| Polymer Matrix | Fillers | Nanocomposite synthesis method | Piezoelectric coefficient d33/d31 [pC N–1] | Poling conditions | Applied load/pressure/strain%/load resistance | Output performance | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filler name | Length [L]/Diameter [D]/Thickness of fillers [T] | Content | Voltage [V] | Current/current density | Power/power density | ||||||

| PVDF nanocomposites based on non‐conducting fillers | |||||||||||

| P(VDF‐HFP) | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 200nm | 30 wt% | Solvent evaporation | – | 100 kV cm–1 at 100 °C for 20 h | 0.23 MPa | 75 | 15 µA | – | [270] |

| P(VDF‐HFP) | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 200nm | 30 wt% | Solvent evaporation | 180 | 100 kV cm–1 at 100 °C for 20 h | 0.23 MPa | 110 | 22 µA | 0.48 W cm–3 | [52] |

| PVDF | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 100nm | 10 wt% | Solvent evaporation assisted 3D printing | 18 | No poling | ≈2.7 N | 4 | – | – | [271] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 100 nm | 0–40 wt% | Ball milling and spin casting | – | 100 MV m–1 at RT for 6 h | 0.5 N mm–2 | 9.8 at 40 wt% |

0.69 µA 1.4 µA cm–2 |

13.5 µW cm–2 | [273] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 100 nm | 0–35 wt% | Electrospinning at 18 kV | – | No poling | 600 N | 25 at 15 wt% | 0.67 µA cm–2 | 2.28 µW cm–2 | [274] |

| PVDF | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 150 nm | 30 wt% | Solvent evaporation | – | 2 kV cm–1 for 8 h | 10 MPa | 150 | 1.5 µA | – | [251] |

| PVDF | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 1 µm | 30 vol% | Hot pressing and calcination | 25 | 5 kV mm–1 at 120 °C for 30 min | – | – | – | – | [253] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 10–100, L=500 nm | 0–20 wt% | Ultra‐sonication | – | 150 MV cm–1 at RT for 1 h | Finger tapping | ≈0.6 | ≈0.5 µA | 0.28 µW at 1 MΩ resistance | [275] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 10–100, L=500 nm | 0–20 wt% | Electrospinning at 20–35 kV | – | No poling | Finger tapping | 5.02 at 20 wt% | – | 25 µW | [276] |

| PVDF | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | – | 1–10 wt% | Solvent casting | – | 1 kV for 30 min at RT | 100 MΩ | 7.2 at 10 wt% | 38 nA | 0.8 µW cm–2 | [277] |

| PVDF | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 200 nm | 0–16 wt% | Electrospinning | – | 8 V for 1 h | 6 mm cyclic deflection | 0.48 at 16 wt% | – | – | [278] |

| PVDF | BaTiO3 fibers |

D = 0.8 µm L = 4.0 µm |

30 vol% | Electrospinning | 11.4 | 35 kV mm–1 at 100 °C for 2 h | – | – | – | – | [279] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | Polydopamine modified BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 120.65 nm | 20 wt% | Electrospinning at 25 kV voltage | – | No poling | 700 N | 6 | 1.5 µA | 8.78 mW m–2 | [280] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 200 nm | 0–50 wt% | Ultra‐sonication | 35.3 | 50 MV m–1 | 0.5 MPa | 13.2 at 20 wt% | 0.33 µA | 12.7 µW cm–2 | [282] |

| PVDF | BaTiO3 nanoparticles | D = 100 nm | 55 wt% | Solvent evaporation | – | 15 MV m–1 at 100 °C for 1 h | 2 N | 10 | 2.5 µA | – | [283] |

| PVDF | BaTi2O5 nanorods | L = few microns | 2.5–20 vol% | Hot pressing | – | 20 kV mm–1 at 80 °C for 6 h. |

22 MΩ acceleration = 10 g |

37.5 at 5 vol% | 1.7 µA | 27.4 µW cm–3 | [254] |

| PVDF | ZnO nanoparticles | D = 100 nm | 1–9 wt% | Solution mixing | – | 50 kV cm–1 at 60 °C | – | – | – | – | [284] |

| PVDF | ZnO nanoparticles | D = 70 nm | 1 wt% | Solution casting | ‐6.4 | No poling | 8.43 kPa | 28 | 450 nA | 0.4 µW | [285] |

| PVDF | ZnO nanoparticles | – | 0.2 mol.% | Sol–gel technique | 900 | 5 MV m–1 for 2 h in vacuum | 1600 N m–2 | 4 | – | – | [286] |

| PVDF | ZnO nanoparticles | D = 15 nm | 15 wt% | Electrospinning at 16 kV | – | No poling | – | 1.1 | – | – | [288] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | ZnO nanoparticles | D = 30 ± 10 nm | 1.5–12.5 wt% | Spin casting | 32.2 at 7.5 wt% ZnO | No poling | 65g load | 7.5 V at 7.5 wt% ZnO | – | – | [289] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | ZnO nanoparticles | D = 20–60 nm | 10 wt% | Ultrasonic mixing | 19‐22 | Corona poling at 14 kV for 5 min | – | – | – | – | [290] |

| PVDF | ZnO nanoparticles | D ≈ 50–150 nm | 0.85 vol. % | In situ process | 50 | No poling | 28 N | 24.5 | 1.7 µA | 32.5 mW cm–3 | [293] |

| PVDF | ZnO nanorods | – | 15 wt% | Ultra‐sonication and drop casting | ‐1.17 | No poling | 15 kPa | 1.81 | 0.57 µA | 0.21 µW cm–2 | [294] |

| PVDF | ZnO nanowires |

D = 0.1 µm L = 2.8 µm |

– | Spin coating | – | 1.2 MV cm–1 | 3.2% strain | 0.4 | 30 nA | – | [295] |

| P(VDF‐HFP) | Co‐doped ZnO nanorods | – | 0.5–2 wt% | Electrospinning at 12 kV | – | No poling | 2.5 N | 2.8 at 2 wt% | – | – | [296] |

| P(VDF‐HFP) | Ni‐doped ZnO nanoparticles | – | 0.5–2 wt% | Solution casting | 20 at 0.5 wt% | No poling | 2.5 N | 1 at 0.5 wt% | 19–21 nA | – | [297] |

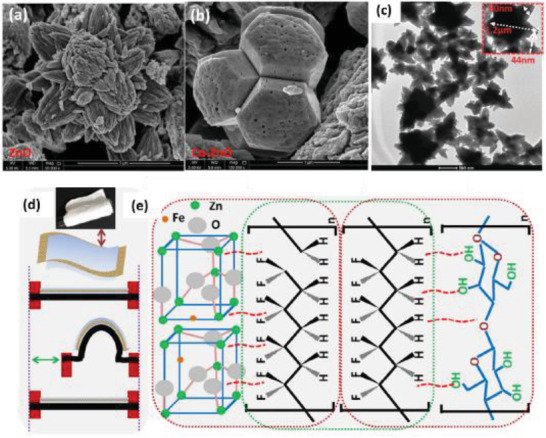

| PVDF | Fe doped ZnO nanoparticles | Star size ≈ 1.2 µm | 2 wt% | Solution casting | 9.44 | No poling | 2.5 N | 2.4 | 25 nA | 1.17 µW cm–2 | [298] |

| P(VDF‐HFP) | Cellulose NC and Fe‐doped ZnO |

W = 44 nm L = 1.2 µm |

2 wt% 2 wt% |

Electrospinning | – | No poling | 2.5 N | 12 | 1.9 µA cm–2 | 490 µW cm–3 | [299] |

| PVDF | Cellulose nanocrystals | – | 1, 3, 5 wt% | Electrospinning at 15 kV | – | No poling | Force by hammer | 6.3 at 5 wt% | 2 µA | – | [300] |

| PVDF | Zirconate titanate nanoparticles | D ≈ 12 nm | 0.5–2 wt% | Solution casting | – | No poling | 16.5 kPa | 25.7 at 2 wt% | 1.2 µA | 8.22 µW cm–2 | [301] |

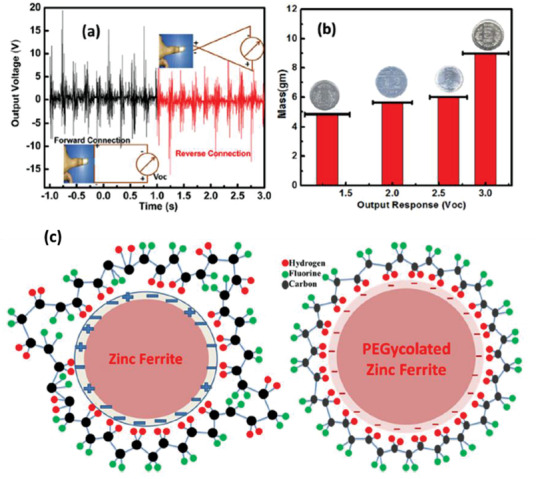

| PVDF | Zinc ferrite modified with TEOS | D = 32 nm | 0.5–1.5 wt% | Drop casting and hot pressing | – | 1.3 V for 2 h | Human finger impact | 2.2 for 1.5 wt% | – | – | [302] |

| PVDF | Zinc ferrite modified with PEG | D = 50 nm | 2–12 wt% | Drop casting and hot pressing | – | No poling | Finger tapping | 18 at 12 wt% | – | – | [303] |

| PVDF | Zinc ferrite spheres, cubic and rod‐like | – | 1–7 wt% | Drop casting and hot pressing | No poling | Finger tapping | 39.1 for 3 wt% nano‐rods | – | 2.96 µW mm–3 | [304] | |

| PVDF | GaFeO3 nanoparticles | – | 10–30 wt% | Solvent casting | – | No poling | – | 4 at 30 wt% | 4 nA | – | [305] |

| PVDF | PZT powders | – | 10–30 vol% | Solution casting | 84 for 30 vol% | 10 kV mm–1 at 80 °C in silicone oil bath | – | – | – | – | [306] |

| PVDF | KNN nanorods | – | 0–6 wt% | Melt mixing and melt spinning | – | Corona poling at 80 °C with 15 kV voltage | Finger tapping | 3.7 at 4 wt% | 0.326 µA | – | [312] |

| PVDF | SiO2 nanoparticles | D = 20–30 nm | 0.5–2 wt% | Electrospinning at 13kV voltage | – | No poling | 13.9 N | 24.6 at 0.5 wt% SiO2 | – | – | [313] |

| PVDF | NiO nanoparticles | D = 44 nm | 0.25–1 wt% | Solution casting | – | No poling | – | – | – | – | [317] |

| PVDF | SiO2 coated NiO nanoparticles | D = 3 µm | 1–15 wt% | Solution casting | – | No poling | 0.3 MPa | 53 | ≈0.3 µA cm–2 | 685 W m–3 | [318] |

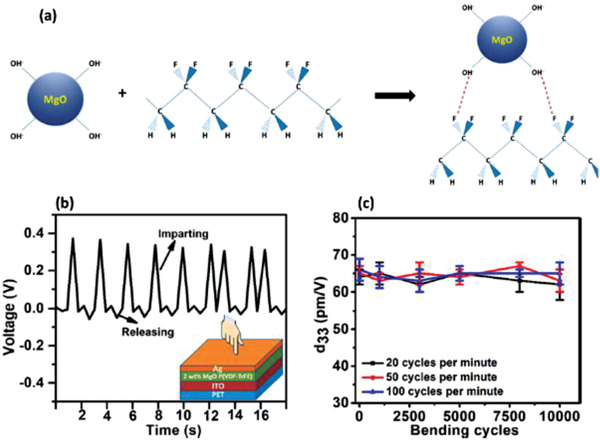

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | MgO nanoparticles | D < 50 nm | 0–8 wt% | Solution casting | −65 at 2 wt% | No poling | Finger tapping | 2 | – | – | [319] |

| PVDF | CoFe2O4 nanoparticles | D = 30–70 nm | 5 wt% | Ultra‐sonication and solvent evaporation | 33 | Corona poling at 80 °C for 0.5 h | – | – | – | – | [320] |

| PVDF | Fe3O4 nanoparticles | D = 6 nm | 0.5–2 wt% | Solution mixing | 37 at 2 wt% | 35 MV m–1 at 60°C for 1 h | [321] | ||||

| PVDF |

Ce‐doped Fe2O3 Ce‐doped Co3O4 nanoparticles |

D = 39 nm D = 29 nm |

2 wt% | Electrospinning at 12 kV | – | No poling | 2.5 N |

20 15 |

0.010 0.005 µA cm–2 |

700.64 334.39 µA cm–3 |

[323] |

| P(VDF‐HFP) | Li doped montmorillonite (Mt) | – | 7–50 wt% | Solution casting | 45 at 15 wt% | No poling | Pressing by fingers | 5 | 50 nA | – | [328] |

| PVDF | Micro‐CaCO3 and Mt particles | – |

30–40 wt% 0–3 wt% |

Twin screw extrusion and stretching | 30.6 at 40 wt% CaCO3 and 3 wt% Mt | Corona poling at 90 V µm–1, RT for 10 min | 0.98 N | – | – | – | [329] |

| PVDF | Laponite nano‐clay | – | 0.1–0.5 wt% | Solvent evaporation | – | No poling | 300 N | 6 at 0.5 wt% | 70 nA | – | [330] |

| PVDF | Nano‐clay | Fiber D = 330 ± 30 nm | 0–20 wt% | Electrospinning at 12.5 kV | – | No poling | Finger tapping | 70 at 15 wt% | ≈20 nA | 68 mW cm–2 | [331] |

| PVDF | Halloysite nanotubes | – | 10 wt% | Electrospinning at 20 kV | – | – | – | Highest output voltage | – | – | [332] |

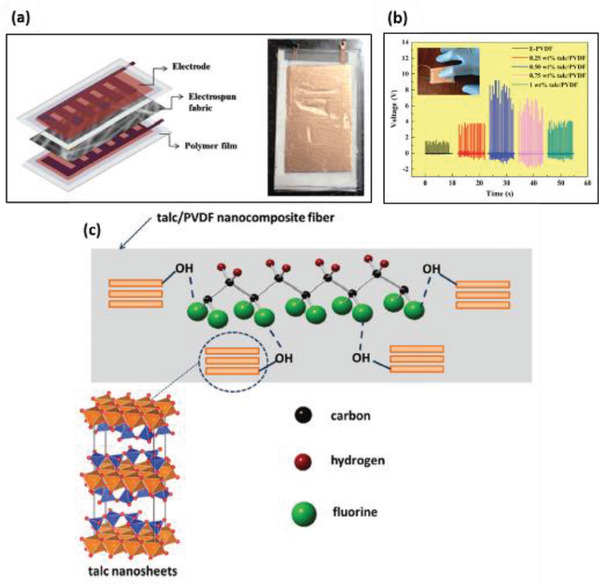

| PVDF | Talc nanoparticles | D < 100 nm | 0.25–1 wt% | Electrospinning at 18 kV | – | No poling | 3.8 N | 9.1 at 0.5 wt% talc | 16.5 nA | 1.12 µW cm–2 | [333] |

| PVDF | Gd5Si4 nanoparticles | D = 470 ± 129 nm | 2.5 and 5 wt% | Spin casting via phase inversion | – | No poling | 2–3 N | ≈1.2 at 5 wt% | – | – | [334] |

| PVDF | MoS2 nanosheets | – | – | Electrospinning | – | No poling | Finger touch | 14 | 8 nA | – | [335] |

| PVDF nanocomposites based on conducting fillers | |||||||||||

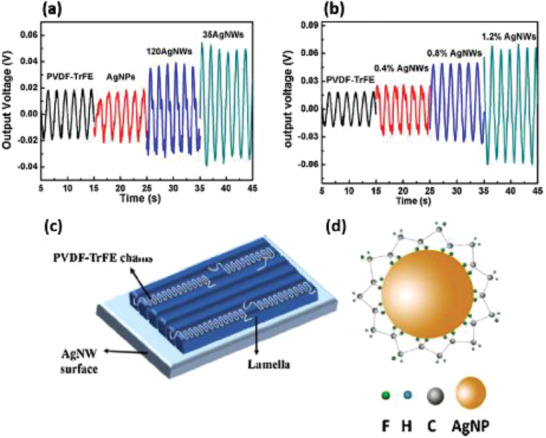

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | Ag nanoparticles | – | 0.005–1 vol% | Sonication and tape casting | 20.23 at 0.005 vol% | No poling | – | – | – | – | [336] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | Ag nanoparticles and Ag nanowires |

D = 20 nm D = 120, 35 nm |

0.4–1.2 wt% | Ultrasonication | – | No poling | – | 0.07 at 1.2 wt% Ag NWs | – | – | [339] |

| PVDF | Ag nanoparticles | D = 25–40 nm | 0–1 wt% | Electrospinning | – | No poling | 1 MΩ load resistance | 2 at 0.4 wt% | 2 µA | – | [340] |

| PVDF | Ag nanowires | D = 40 nm | 0–3 wt% | Electrospinning at 12 kV | 30 at 1.5 wt% | No poling | – | – | – | – | [341] |

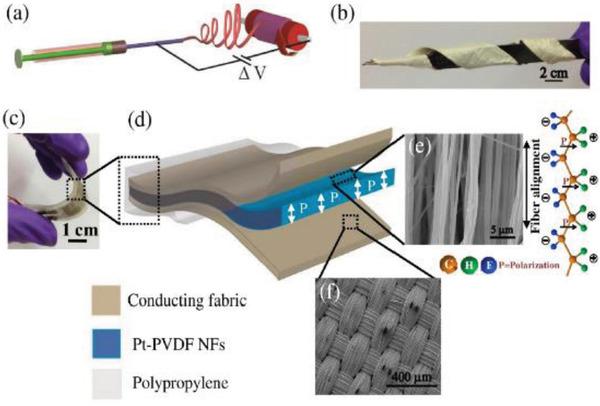

| PVDF | Pt nanoparticles | D = 600 nm of Pt/PVDF Nfs | 1.5 wt% | Electrospinning at 150 kVm–1 | 44 | No poling | 0.3 MPa | 30 | 6 mA cm–2 | 22 µW cm–2 | [342] |

| PVDF | SnO2 nanosheets | Thickness ≈ 100 ± 5 µm | 5 wt% | Solution casting | 36.52 | No poling | 0.3 MPa | 42 | 6.25 µA cm–2 | 4900 W m–3 | [343] |

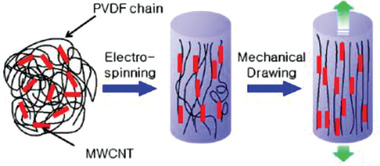

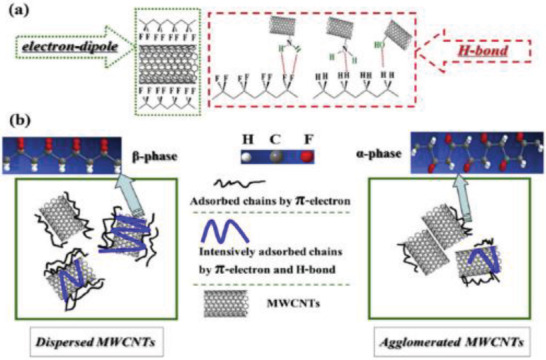

| PVDF | MWCNTs | D = 10–15 nm | 0.05–1 wt% | Electrospinning at 14 kV | – | 500 kV cm–1 at 120°C for 20 min in silicone oil bath | – | – | – | – | [263, 337] |

| PVDF | MWCNTs | – | 0–0.05 wt% | Near field Electrospinning | −57.6 | In situ poling at 1200 V mm–1 | – | – | – | – | [203, 345] |

| PVDF | MWCNTs | – | 3–10 wt% | Electrospinning at 18 kV | – | No poling | 4 MPa | 6 at 5 wt% | – | 81.8 nW | [347] |

| PVDF | CNTs | D = 10–20 nm | 18 wt% | Electrospinning | 31.3 | No poling | 350 N | 1.89 | 11 nA | – | [348] |

| PVDF | MWCNTs |

D = 40–90 nm AR > 100 |

0–0.3 wt% | Solution casting | – | Stepwise poling at 60 MV m–1 | – | 3.7 at 0.05 wt% | – | – | [262] |

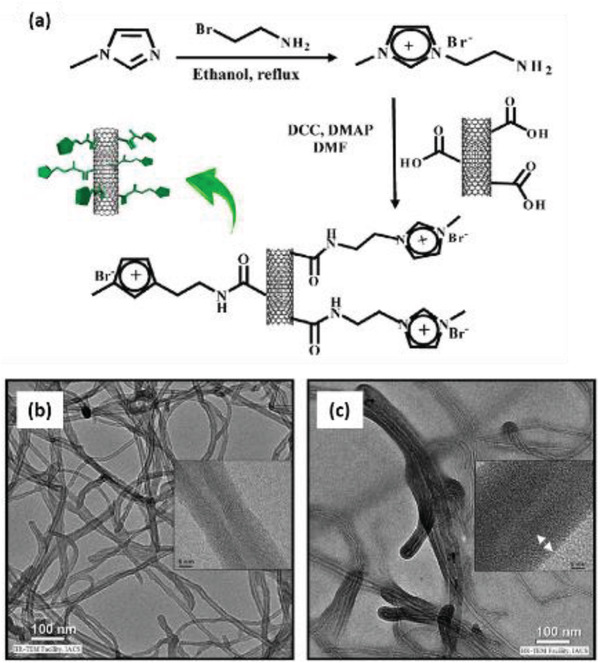

| PVDF | MWCNTs functionalized with IL |

D = 20–30 nm L = 0.5–200 µm |

0.05–1 wt% | Solvent casting and melt blending | – | – | – | – | – | – | [349] |

| PVDF | MWCNTs functionalized with carboxyl, amino & hydroxyl groups |

D = 9.5 nm L ≈ 1 µm |

1.5–5 wt% | Melt mixing | – | – | – | – | – | – | [350] |

| PVDF | COOH functionalized CNTs & Ag‐CNTs | D = 1.3–1.9 µm of fibers | 1 wt% | Electrospinning at 15 kV | 54 pm V–1 for Ag‐CNTs | No poling | – | – | – | – | [351] |

| PVDF | Unzipped MWCNTs |

D = 30 nm L = 10 µm |

0.3 wt% | Solution coagulation | 38.4 | No poling | – | – | – | – | [352] |

| PVDF | MWCNTs coated with TiO2 | D = 40–60 nm L = 5–15 µm | 0–1 wt% | Solution casting | 41 at 0.3 wt% |

120 V µm–1 at 70 °C for 1.2 h |

– | – | – | – | [354] |

| PVDF | Buckminster fullerenes (C60) and SWCNTs | – | 0–0.25 wt% | Ultrasonication | 65 at 0.05 wt% SWCNT |

20 kV at 80 °C for 20 min |

0.46 N | – | – | – | [355] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | Graphene | – | 0–0.15 wt% | Solution casting | 34.3 ± 7.2 | Stepwise from 10 to 60 MV m–1, 10 MV m–1 per step | 20.37 MΩ | 12.43 at 0.15 wt% | 0.6 µA | 148.06 W m–3 | [357] |

| PVDF | Graphene nanoplatelets | – | 0–5 wt% | Electrospinning at 20 kV | – | No poling | – | 7.9 at 0.1 wt% | 4.5 µA | – | [358] |

| PVDF | Graphene nanoplatelets | L = 2–10 µm | 2–5 wt% | Solution casting | – | No poling | – | – | – | – | [359] |

| PVDF | Graphite nanosheets | T < 200 nm | 1–7 mL | Solution casting | 6.7 at 6 mL | 50 kV mm–1 for 30 min at 130 °C | – | – | – | – | [360] |

| PVDF | Ce3+ doped Graphene | D = 80 nm of nanofibers |

0.2 wt% 1 wt% |

Electrospinning at 12 kV | – | No poling | 6.6 kPa | 11 | 0.07 µA | 0.56 µW cm–2 | [361] |

| PVDF | Graphene‐Ag doped nanosheets | D = 55 nm for Ag NPs | – | Solution casting | – | No poling | 5.2 kPa | 0.1 | 0.1 nA | – | [362] |

| PVDF | PMMA functionalized graphene | T = 2–4.5 nm | 0.5–5 wt% | Sonication and solvent evaporation | – | No poling | – | – | – | – | [261] |

| PVDF | Graphene and polybenzoxazole | D = 60 µm | 0.3 wt% | Electrospinning at 16 kV | – | No poling | – | 60 | – | – | [363] |

| PVDF | Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) | – | 0–0.2 wt% | Solution casting | – | Stepwise poling at 60 MV m–1 at 8 min intervals | Vibration test at 30 Hz | 3.28 at 0.05 wt% | – | – | [338] |

| PVDF | Reduced graphene oxide |

T = 1 nm L = 100–600 nm |

0.1–0.3 wt% | Ultrasonication and hot pressing | – | Corona poling at 12 kV, 60 °C for 30 min | – | 1.3 V at 0.1 wt% | – | 36 nW at 704 kΩ resistance | [364, 365] |

| PVDF | Reduced graphene oxide | D = 10–15 nm | 0.1–1 wt% | Ultrasonication and compression molding | – | – | 500 g | 0.45 at 1 wt% rGO | 0.15 µA | 14 µW cm–3 | [366] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | Reduced graphene oxide |

W = 80 nm L = 300 nm |

0–0.2 wt% | Drop casting | −23 at 0.1 wt% | No poling | 3.2 µW | 2.4 at 0.1 wt% | 0.8 | 2 N | [367] |

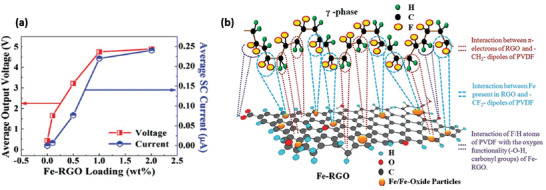

| PVDF | Fe doped rGO | – | 0.1–2 wt% | Ultrasonication | – | No poling | 12 kPa | 5.1 at 2 wt% Fe‐rGO | 0.254 µA | – | [368] |

| PVDF | Ag doped rGO | – | 0.1–2 wt% | Ultrasonication and centrifugation | – | No poling | 1 MΩ load resistance | 18 at 1 wt% Ag‐rGO | 1.05 µA | 28 W m–3 | [369] |

| PVDF | ZnO doped rGO | – | rGO/ZnO ratio 1:1, 2:1, 4:1 | Solution casting | – | No poling | – | – | – | – | [370] |

| PVDF | AlO doped rGO | D ≈ 30–40 nm | 1 wt% | Solution casting | 45 | No poling | 31.19 kPa | 36 | 0.8 µA | 27.97 µW cm–3 | [371] |

| PVDF | CdS doped rGO | – | 0.25 wt% | Electrospinning | – | No poling | Finger imparting | 4 | – | – | [372] |

| PVDF | Fe‐rGO and CNTs | – | – | – | – | No poling | Finger excitation |

2.5 for rGO 1.2 for CNTs |

0.7 µA 0.3 µA |

– | [373] |

| PVDF | Graphene oxide nanosheets |

T ≈ 1 nm L ≈ 100–800 nm |

0.05–2 wt% | Solution casting | – | No poling | – | – | – | – | [374] |

| PVDF | Graphene oxide |

T ≈ 13 nm L ≈ 0.3 µm |

2 wt% | Drop casting | – | No poling | – | – | – | – | [377] |

| PVDF | Graphene oxide |

T = 0.7–1.4 nm L = 5–100 µm |

0–5 wt% | Non‐solvent induced phase separation | – | No poling | – | 2.64 at 0.5 wt% | – | – | [260] |

| PVDF | Carboxylated and fluorinated graphene oxide | D = 600–700 nm | 1 wt% | Electrospinning at 16 kV | 63 for fluorinated GO | No poling | – | – | – | – | [378] |

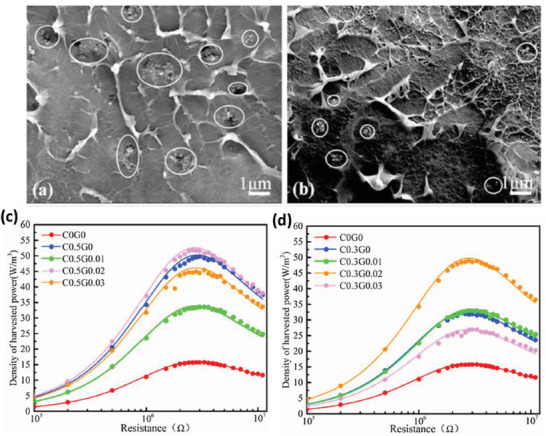

| P(VDF‐HFP) | Carbon black nanoparticles | D ≈ 36 nm | 0–0.8 wt% | Solution casting | – | Poling at 90 MV m–1 | – | 3.68 at 0.5 wt% | – | 13 W m–3 | [264] |

| P(VDF‐HFP) | Carbon black (CB) and few layer graphene (FLG) |

D = 50–100 nm D = 0.5–5 nm |

0–0.8 wt% 0–0.03 wt% |

Ultrasonication | – | Stepwise from 20 to 90 MV m–1, 10 MV m–1 per step | 2 MΩ | 4.1 at 0.5 wt% CB and 0.02 wt% FLG | 2 µA | 51.9 W m–3 | [265] |

| PVDF nanocomposites based on conducting and non‐conducting filler combination | |||||||||||

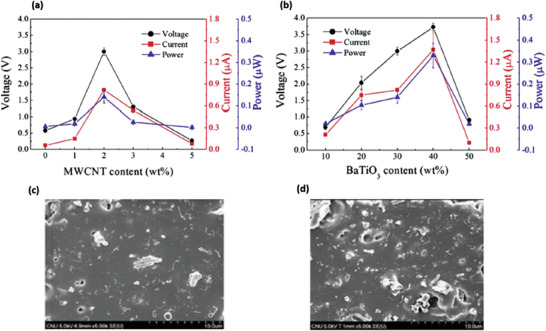

| PVDF | BaTiO3 nanoparticles and MWCNTs |

D = 700 nm D = 8–15 nm L = 10–50 µm |

18 wt% 0.4 wt% |

FDM 3D printing | d31 = 0.13 at 0.4 wt% MWCNT 18 wt% BaTiO3 | 5.4 MV m–1 for 15 h | 80 N | 0.43 | 0.94 nA | – | [379] |

| P(VDF‐HFP) | BaTiO3 NPs and hexagonal boron nitride nanolayers | – | 3 wt% BaTiO3 1 wt% h‐BN | Solution mixing | – | – | – | 2.4 | – | – | [380] |

| PVDF | BaTiO3and graphene quantum dots | D < 100 nm |

2 wt% 1.5 wt% |

Spin casting | – | No poling | 265 mN | 4.6 | 4.13 pA cm–2 | 11.2 µW cm–3 | [381] |

| PVDF | TiO2 nanolayers and rGO |

D = 15 nm T = 1.5 nm |

2.5 wt% of each | Solution mixing | – | No poling | – | – | – | – | [382] |

| PVDF | TiO2 nanotubes and CNT | – | 1–5 wt% | Solution casting | – | Corona poling at 8 kV for 7 s | 2.5 N | 1.3 at 1 wt% | – | – | [383] |

| P(VDF‐HFP) | TiO2‐rGO nanotubes and SrTiO3 nanoparticles | SrTiO3 D < 100 nm |

1 wt% TiO2‐rGO 2 wt% SrTiO3 |

Solvent casting | 7.52 | Corona poling | – | 2 | – | – | [267] |

| PVDF | NaNbO3 nanorods and rGO |

L = 200, D = 50 nm T ≈ few layers |

0.1 wt% | Ultrasonic mixing | – | – | 15 kPa | 2.16 | 0.383 µA | – | [266] |

| PVDF | Fe3O4‐Graphene oxide nanoparticles‐nanosheets | Fiber D = 117–710 nm | 0–2 wt% | Solution mixing and Electrospinning at 12 kV | 1.75 at 2 wt% | No poling | 1.32 N | 0.23 at 2 wt% | – | – | [385] |

| PVDF | TiO2‐Fe3O4‐MWCNT nanotubes | Fiber D = 70 µm | 0–2 wt% | Electrospinning at 12 kV | 51.42 at 2 wt% | No poling | 1.32 N | 0.68 at 2 wt% | – | – | [386] |

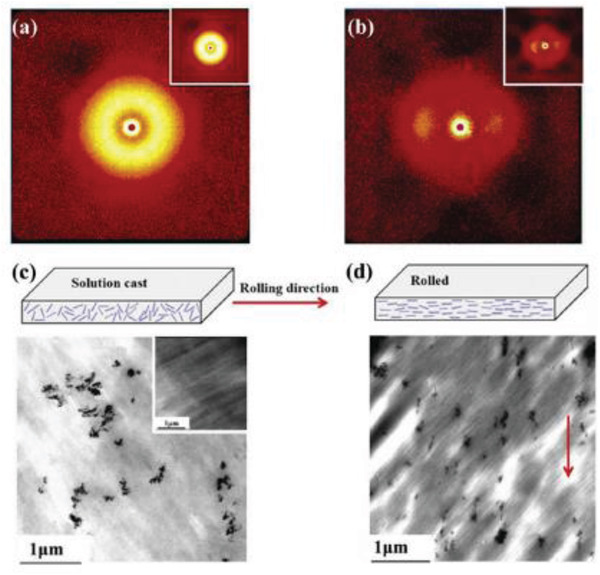

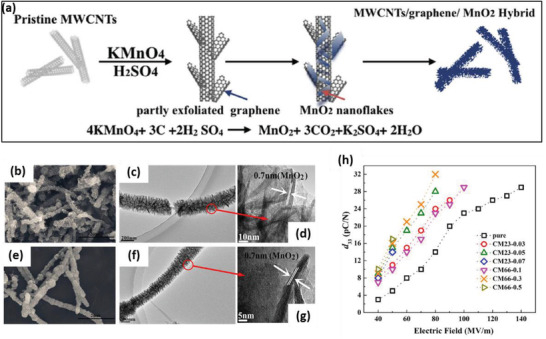

| PVDF | MnO2/graphene/MWCNT hybrid | D = 240–300 nm | 0.2–1 wt% | Solution casting and rolling | 17‐33 | 50–80 MV m–1 | – | – | – | – | [268] |

| PVDF | Graphene oxide, graphene, halloysite nanotubes |

D = 3.4–7 nm D = 2–18 nm D = 30–70 nm, L = 2–3 µm |

0.05–3.2 wt% | Electrospinning | 5 for 0.8 halloysite | No poling | 0.49 N | 0.1 for 0.8 halloysite | 0.1 µA | – | [387] |

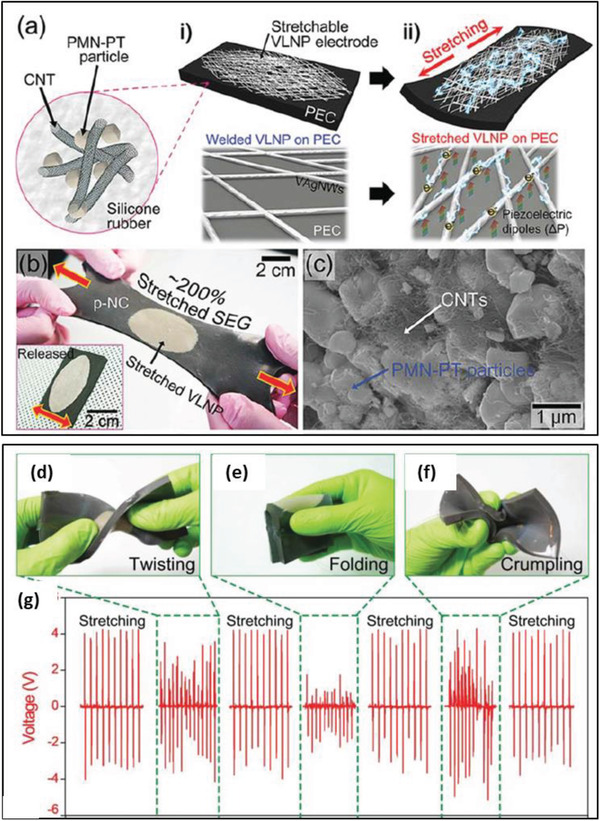

| PVDF |

PMN‐PT particles CNTs |

– |

30 vol% 1 vol% |

Magnetic stirring and heat treatment | – | – | – | 4 | 30 nA | – | [389] |

| PVDF |

Cellulose rods Carbon nanotubes kaolinite clay nanoparticles |

D = 15–30 µm; L = 124–400 µm; D = 10–30 nm L = 2–3 µm; D = 1.2 µm |

0.5–2 wt% | Solution casting | – | No poling | – | – | – | – | [390] |

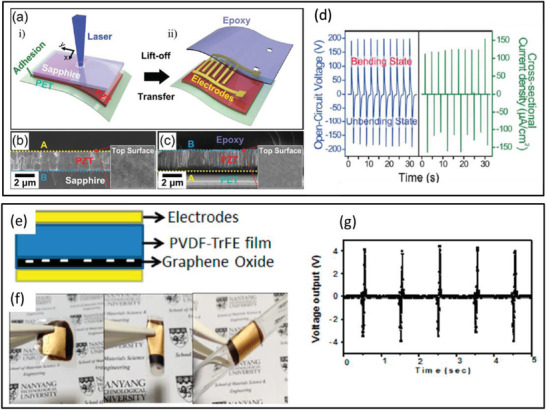

| PDMS nanocomposites based on non‐conducting fillers | |||||||||||

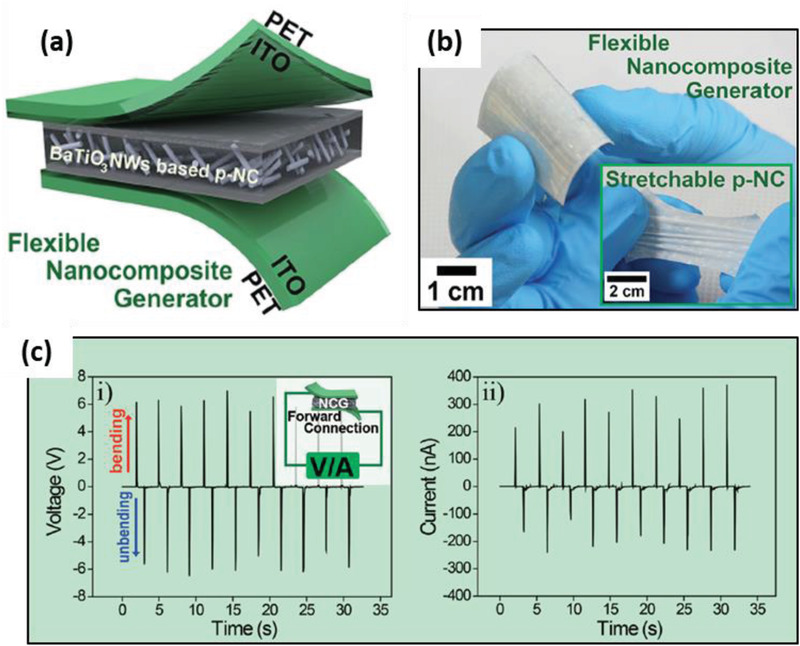

| PDMS | BaTiO3 nanowires |

L ≈ 4 µm D ≈ 156 nm |

5–20 wt% | Spin casting | – | E = 0.5–1.5 kV at 140 °C for 12 h | Bending and unbending | 7 | 360 nA | ≈1.2 µW at 20 MΩ | [392] |

| PDMS | BaTiO3 nanoparticles and nanowires |

D = 120 nm L = few microns |

13 wt% | Magnetic stirring and spin casting | – | 1 kV at 120 °C for 12 h | Bending and unbending | 60 | 1.1 µA | 40 µW at 500 MΩ | [393] |

| PDMS | BaTiO3 nanotubes |

D = 11.8 nm L = 4.1 µm |

1–4 wt% | Spin casting | – | 80 kV cm–1 at ambient temp. for 12 h | 1 MPa | 5.5 |

350 nA j = 350 nA cm–2 |

– | [394] |

| PDMS | BaTiO3 nanofibers |

D = 0.7–0.9 nm L = 1.7 mm |

31 wt% | Ultrasonication and curing | – | 5 kV mm–1 at 120 °C for 12 h | 0.002 MPa | 2.67 | 261.4 nA | 0.1841 µW | [395] |

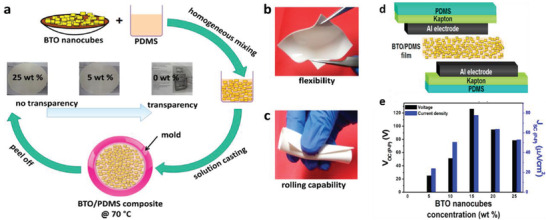

| PDMS | BaTiO3 nanocubes | D = 100–400 nm | 10–25 wt% | Solution casting | – | 8 kV at RT for 24 h | 988.14 Pa | 126.3 at 15 wt% | 77.6 µA cm–2 | ≈7 mW cm–2 at 100 MΩ | [396] |

| PDMS | BaTiO3 nanocrystals | D = 50–100 nm | 20 wt% | Solution casting and curing | – | 2 kV at 130 °C for 12 h | – | 6 | 300 nA | – | [397] |

| PDMS | ZnSO3 nanocubes | Edge size = 100–200 nm | 10–60 wt% | Centrifugal mixing | – | No poling | 0.91% strain | 12 at 40 wt% | 0.89 µA cm–2 at 40 wt% | – | [398] |

| PDMS | Li doped ZnO nanowires | – | 10 wt% | Spin casting and curing | – | 105 kV cm–1 at 65 °C for 20 h | 0.91% strain | 180 | 50 µA | – | [399] |

| PDMS | NaNbO3 nanowires |

D ≈ 200 nm L ≈ 10 µm |

1 vol% | Spin coating | – | ≈80 kV cm–1 at RT | 0.23% strain | 3.2 |

72 nA 16 nA cm–2 |

0.6 mW cm–3 | [401] |

| PDMS | LiNbO3 nanowires |

D ≈ 100–250 nm L ≈ 50 µm |

1 vol% | Mixing and spin coating | 25 for LiNbO3 nanowires | 100 kV cm–1 at RT | 105 strain cycles | 0.46 | 0.009 | – | [41] |

| PDMS | PZT nanotubes | L = 59 mm; D = 210 nm | 1:100 vol. ratio | Mixing | – | Corona poling at 1.5 kV | 980 N m−1 | 1.52 | 54.5 nA | 37 nW cm–2 | [44] |

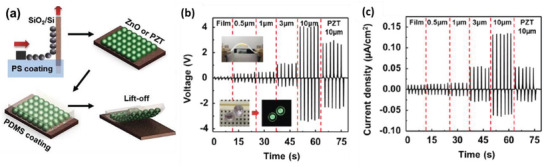

| PDMS | ZnO or PZT hemispheres | D = 10 µm | – | LB deposition and magnetron sputtering | – | No poling | 0.425% strain |

6 3 |

0.2 µA cm–2 0.05 µA cm–2 |

– | [402] |

| PDMS | PMN‐PT nanowires | L ≈ 10 µm | 10 wt% | Mechanical mixing and curing | – | 5 kV mm–1 at 150 °C in silicone oil bath for 24 h | – | 7.8 | 2.29 µA | – | [403] |

| PDMS | BiFeO3 nanoparticles | – | 10–40 wt% | Mixing and spin casting | – | 200 kV cm–1 at 150 °C for 10 h | 10 kPa | 3 at 40 wt% | 0.25 µA at 40 wt% | – | [64] |

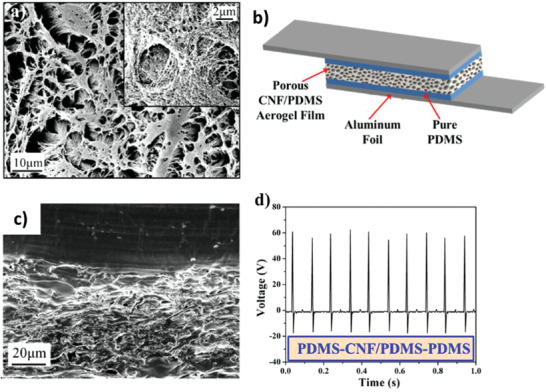

| PDMS | Cellulose nanofibril | – | 0.85 wt% | Spin coating | 19 | No poling | 0.05 MPa | 60.2 | 10.1 µA | 6.3 mW cm–3 | [405] |

| PDMS | FAPbBr3 nanoparticles | D = 50–80 nm | 35 wt% | Centrifugal mixing | – |

50 kV cm–1 in dry the atmosphere at RT for 12 h. |

0.5 MPa | 8.5 | 3.8 µA cm–2 | 12 µW cm−2 at 800 kΩ | [407] |

| PDMS | Aurivillius‐based oxide [CaBi4Ti4O15] |

D = 10 mm T = 1 mm |

1–12 wt% | Solution casting | – | 2 kV for 1 h in silicon oil bath | 300 MΩ | 23 at 8 wt% | 85 nA | 1.09 mW m–2 | [411] |

| PDMS nanocomposites based on conducting and non‐conducting filler combination | |||||||||||

| PDMS | BaTiO3 NPs, SW/MWCNTs or rGO |

D = 100 nm D = 5–20 nm, L ≈ 10 µm |

12 wt% 1 wt% |

Ultrasonic mixing and spin casting | – | 100 kV cm–1 at 150 °C for 20 h | 57 kPa |

3.2 2 |

350 nA | – | [125] |

| PDMS | BaTiO3 nanofibers and MWCNTs |

L ≈ 33.7 mm, D ≈ 354.1 nm 10–15 nm, L = 10–20 µm |

10–50 wt% 0–5 wt% |

Ultrasonic mixing and spin casting | – | 5 kV mm–1 for 12 h in silicone oil bath | 2 kPa |

3 for 30‐BaTiO3/0.5‐CNTs 3.73 for 40‐BaTiO3/2‐CNTs |

0.82 µA 1.37 µA |

0.14 µW 0.33 µW |

[412] |

| PDMS | BaTiO3 nanoparticles and carbon black |

D = 1.2 ± 0.6 µm D = 30 nm |

30 wt% 0–4.8 wt% |

Ball milling and mixing | 15.3 | 30 kV mm–1 at 100 °C for 20 h | Periodic beating by vibrator | 7.43 at 3.2 wt% C | 5.13 | 1.98 µW cm–2 | [413] |

| PDMS | ZnO nanoparticles and MWCNTs |

D = 30 nm D = 8–15 nm, L = 50 µm |

12 wt% 1 wt% |

Mechanical mixing | – | No poling | – | 7.5 | 2500 nA | 18.75 µW at 5.64 MΩ | [414] |

| PDMS | PZT and MWCNTs |

D ≈ 1 µm D ≈ 15nm, L ≈ 10 µm |

12 wt% 1 wt% |

Ball milling and stirring | – | 2 kV at 140 °C for 12 h | Periodic stress by a linear motor | 100 | 10 | – | [415] |

| Eco flex silicone rubber | PMN‐PT and MWCNTs |

D ≈ 1 µm D ≈ 20 nm, L ≈ 10 µm |

20 wt% | Blending and curing | – | 50 kV cm–1 at 110 °C | Twisting, folding, pressing | 4 | 500 nA | – | [416] |

| PDMS | KNLN particles and Cu nanorods |

D = 1–3 µm D = 200–400 nm, L ≈ 5 µm |

– | Magnetic stirring, spin coating + curing | – | 2 kV at 150 °C for 12 h | Bending and un‐bending by linear motor | 12 | 1.2 µA | – | [418] |

| PDMS | Cellulose microfiber and MWCNTs |

D = 10 µm D = 9.5 nm, L = 1.5 µm |

5 wt% 0.5 wt% |

Mechanical agitation | 15 | No poling | 40 kPa | 30 | 500 nA | 9 µW cm–3 | [419] |

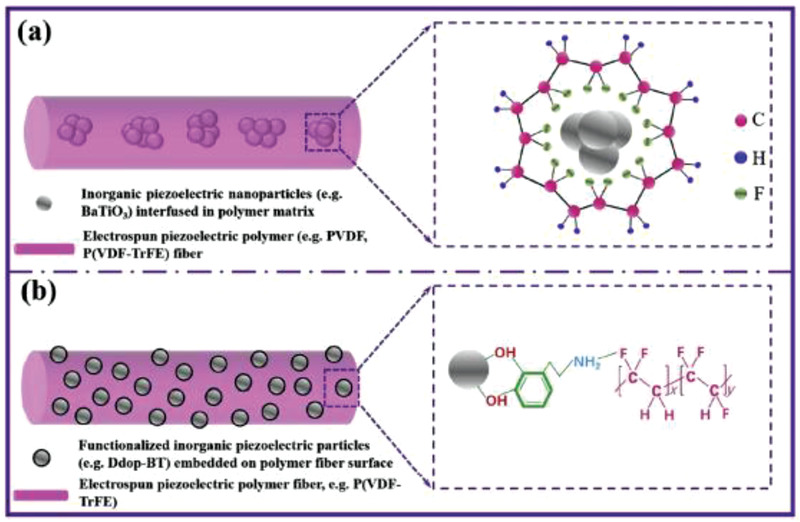

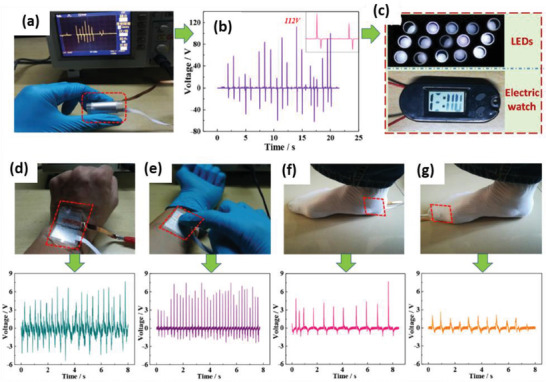

This paper aims to present a holistic review of the recent developments in piezoelectric nanostructured materials, polymers, polymer nanocomposites, and piezoelectric films for implementation in energy harvesting. The paper is structured into nine sections. Following the introduction, the second section covers the theory and mechanism of piezoelectricity. The third section covers fabrication methods, piezoelectric properties, energy harvesting performance, and mechanisms of piezoelectric nanogenerators (PENGs) built using nanostructured materials. In the fourth section, the piezoelectric properties of PVDF based polymers and their copolymers along with other polymers such as, polylactic acid (PLA), polyureas, polyamides, polyacrylonitrile (PAN) are outlined. The fifth section is dedicated to the synthesis, piezoelectric properties, mechanisms, and energy harvesting capabilities of PVDF and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) based polymer nanocomposites prepared using different types of fillers. The sixth section discusses the piezoelectric performance of PVDF films doped with inorganic salts such as magnesium chloride, nickel chloride, iron nitrate, and zinc nitrate. The seventh section is a brief overview of energy harvesting using piezoelectric films. The eighth section describes some examples of the application of PEHs for wireless devices and self‐powered sensors. The last section summarizes the paper and provides insight into the current challenges and future perspectives of piezoelectric energy harvesting.

2. Piezoelectric Effect: Theory and Mechanism

Pierre Curie and Jacques Curie were the pioneers who discovered the phenomenon of piezoelectricity in 1880 while conducting studies in crystals of quartz, tourmaline, and Rochelle salt.[ 53 ] There are two distinct piezoelectric effects, namely, the direct effect and inverse effect. In the direct piezoelectric effect, a material is polarized and produces voltage under an applied tensile or compressive stress. In the inverse effect, the application of electric potential induces mechanical displacement in the material. The constitutive Equations (1) and (2) for both the effects are given below.[ 54, 55 ]

| (1) |

| (2) |

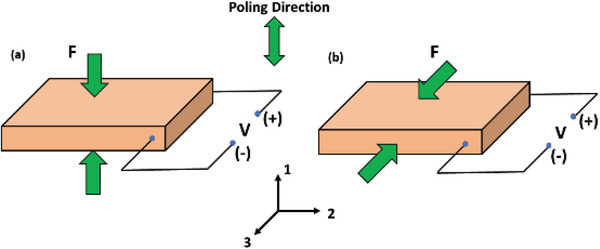

where T = stress, d = piezoelectric constant, S = strain, D = electric displacement, and E = electric field. sE is the mechanical compliance at constant electric field E, ɛT is the permittivity of the material at constant stress T. The subscripts i, j, and k refers to the different directions in the material coordinate system. They are analogous to the Cartesian coordinate axes (x, y, z) and have a value of 1 to 3. The rotational motion around the three axes (1, 2, and 3) is denoted by subscript “m,” hence it has a value of 1 to 6. A piezoelectric energy harvesting device has two primary operating modes: mode 33, in which applied stress is in the direction of polarization (Figure 1a) and mode 31, in which applied stress is perpendicular to the direction of polarization[ 54, 56 ] (Figure 1b). The shear mode denoted by 14 is less commonly used.

Figure 1.

Operating modes of a piezoelectric material a) 33 mode and b) 31 mode.

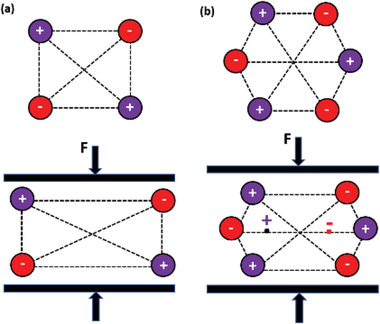

The piezoelectric effect originates from the distribution of ions in the crystalline structure of certain materials. In the absence of an external force, there exists a steady‐state equilibrium between the positive and negative electric charges in the material, therefore it remains neutral. When a square‐shaped structure is subjected to compressive stress (Figure 2a), the equivalent center of charge is still at the same point, hence there is no change in polarization. For a 2 D hexagon (Figure 2b), when stress is applied, a change is triggered in the center of charge of the cations and anions that induces a change in polarization. There are 32 crystallographic classes, out of which 21 are non‐centrosymmetric (lacking center of symmetry) and 20 of them exhibit direct piezoelectricity; the 21st being the cubic class.[ 57 ] In these materials, due to the absence of symmetry in the ion distribution, electrical dipoles are present, resulting in a piezoelectric response. This behavior is seen in materials such as aluminum nitride and zinc oxide (ZnO).

Figure 2.

Schematic of 2 D crystal structures. a) Non‐piezoelectric square. b) Piezoelectric hexagon.

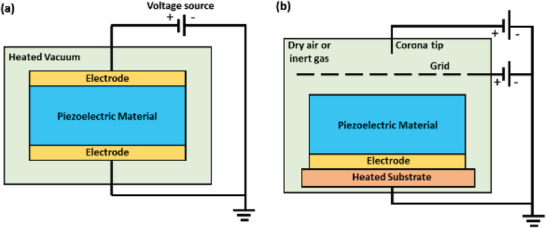

In most other materials, the molecular dipoles are randomly oriented within their crystal structure. To obtain an effective piezoelectric response from such materials, an important operation called “poling” is done. In the process of poling, the molecular dipoles in a material are re‐oriented by exerting a high electric field at high temperature, followed by subsequent cooling keeping the same electric field to sustain the orientation state. The two well‐known methods of poling are electrode poling and corona poling. A high voltage is applied to the piezoelectric material in electrode poling by pressing conductive electrodes on two sides of the material[ 58 ] (Figure 3a). An electric field in the range of 5–100 MV m–1 is usually applied.[ 59, 60, 61, 62 ] In the corona poling process (Figure 3b), a needle with high conductivity is maintained at extremely high voltage (8–20 kV) and is located on a grid at a lower voltage (0.2–3 kV). The piezoelectric material is situated beneath the grid and is kept in an atmosphere of dry air or inert gas.[ 59, 61, 63 ] Due to ionization around the corona tip, the gas molecules get accelerated toward the piezoelectric material surface. The bottom side of the material is covered with an electrode, which is in contact with a hot substrate to achieve better control over poling. The poling temperature does not exceed 300 °C for both methods in all material cases.[ 31 ]

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram showing the poling systems. a) Electrode poling. b) Corona poling.

2.1. Piezoelectric Effect: Utilization in Energy Harvesting

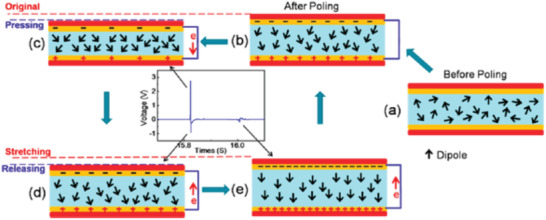

In energy harvesting, the direct piezoelectric effect is utilized, wherein an applied force leads to electrical charge generation. Figure 4 schematically shows the working mechanism of an energy harvester. Initially, in the absence of poling, the dipoles present in the piezoelectric material align randomly between two electrodes[ 64 ] (Figure 4a). Upon application of an electrical field to the energy harvester, the dipoles align in the same direction as the applied field (Figure 4b). In the absence of external force, zero electric signal is acquired by the device because it remains in a state of equilibrium. Under the application of compressive force in the vertical direction, the material is polarized due to compressive strain, inducing piezoelectric potential between the electrodes. In the course of this process, an output signal is acquired (Figure 4c). On releasing the applied force, a slight tensile force develops that induces a reverse piezoelectric potential (Figure 4d,e).

Figure 4.

Diagram showing the working mechanism of an energy harvester. Reproduced with permission.[ 64 ] Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society.

For energy harvesting, when mechanical stress (Δσ) is applied, the charge (Q) generated across the opposite faces of a piezoelectric material of area (A) is defined by Equation (3).[ 65 ]

| (3) |

The material's piezoelectric coefficient (pC N–1) in 33‐mode is denoted by d33. Load impedance is infinite under open‐circuit conditions, hence the equation Q = CV is used, where C is the capacitance of the material () and is used to calculate voltage (V) from Equation (4).

| (4) |

where “h” is material thickness and is the permittivity at a constant stress value in 33‐mode. By substituting “V” from Equation (4) in the expression , the energy E due to applied stress is defined by Equation (5).

| (5) |

Therefore, for a certain thickness and area, the energy obtained from a piezoelectric device can be maximized by choosing piezoelectric materials with large it is known as harvesting Figure of merit. Under short circuit conditions, the current (I) is given by (Equation (3)) and can be written as Equation (6).

| (6) |

In energy harvesting applications, open and closed‐circuit measurements are frequently performed. However, there is no effective power at these conditions because the current is zero at the open circuit and there is no potential difference at the closed circuit. The instantaneous power density is calculated using the formula ,[ 66, 67, 68 ] where A is the effective area of the electrodes and the voltage across load resistance R is denoted by V.

There is a coupling coefficient, k, which denotes the efficiency of energy conversion in generator mode and is given by Equation (7).[ 54, 69 ]

| (7) |

The coupling coefficient in 33‐mode and 31‐mode is denoted by and. The greater the coupling coefficient k, the higher the mechanical energy that can be scavenged.

3. Piezoelectric Nanostructured Materials

In the last decade, piezoelectric nanostructured materials for energy harvesting applications have expanded rapidly.[ 70, 71 ] The majority of the reported work is on ZnO because its nanostructures form easily at low temperatures and are crystallographically aligned.[ 72 ] Recently, other materials such as PZT, BaTiO3, and PMN‐PT have been explored as well for nanostructured energy harvesters motivated by their high piezoelectric coefficients. This section summarizes the synthesis techniques, piezoelectric properties, and energy harvesting performance of nanostructured materials.

3.1. 1D ZnO Nanostructures

ZnO has diverse nanostructures and exhibits both semiconducting and piezoelectric properties because of its non‐centrosymmetric crystal structure,[ 73, 74, 75, 76 ] comprising alternating planes of O2– and Zn2+ ions in tetrahedral coordination piled up along the c‐axis.[ 74 ] For ZnO, the piezoelectric constant d33 has been reported in the range of 10–12 pC N–1.[ 77, 78 ] The first study was reported by Z. L. Wang et al., in 2006,[ 73 ] wherein aligned ZnO nanowire (NW) arrays were grown on Al2O3 support via a vapor–liquid–solid based process, utilizing gold (Au) as a catalyst.[ 73, 79 ] Atomic force microscopy (AFM) using a‐Si tip coated with Pt was used to conduct piezoelectricity measurements. The majority of the Au particles on the NW tips either evaporated during the growth or dropped off when deflected by the AFM tip. The grown NW arrays had smaller lengths ranging between 0.2 and 0.5 µm and comparatively lower densities, enabling the AFM tip to solely reach a single NW without interfering with another. The mechanism of power generation was attributed to two factors‐ first, strain field generation and charge detachment throughout the NWs due to bending by AFM tip and second, Schottky barrier formed between the AFM tip and the ZnO NWs. Similarly, Lu et al. synthesized phosphorus‐doped ZnO NWs on Si substrates that produced electricity when bent by an AFM tip.[ 80 ] A voltage of up to 50–90 mV was generated by the p‐type ZnO NWs, whereas the n‐type ZnO NWs generated negative output in the range of −5 to −10 mV.

Yang et al. demonstrated the transformation of biomechanical energy from the movement of a human finger and live hamster into electrical energy with the help of a ZnO NW based nanogenerator (NG).[ 81 ] A single wire nanogenerator (SWG) was fabricated by firmly attaching the two ends of a ZnO NW to metal electrodes packaged on a flexible polyimide substrate.[ 82, 83 ] A higher output voltage was obtained by integrating multiple SWGs, resulting in a voltage of ≈0.1–0.15 V using four SWGs in series.

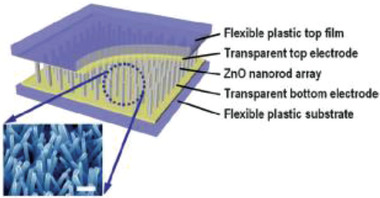

Choi et al., in 2009, reported a ZnO nanostructure‐based completely flexible PENG for applications in self‐powered sensors for the first time.[ 84 ] ZnO nanorods (NRs) were synthesized from a solution of zinc nitrate hexahydrate [Zn(NO3)2.6H2O] and hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA) at 95 °C. A flexible polyethersulfone (PES) substrate coated with indium tin oxide (ITO) was utilized to grow the NR arrays (Figure 5). Top electrodes comprising of ITO coated PES with and without palladium gold (PdAu) film were located on top of the ZnO NR arrays as shown in Figure 5. An output current density of j ≈ 1 µA cm–2 was obtained from the PENG of dimensions 3 cm x 3 cm, when compressed by a force of 0.9 kgf. It was inferred that the Schottky contact between the ZnO NRs and top electrodes helped in the high current generation as proposed in previous studies.[ 73 ] In the next year, the same group reported a transparent, flexible PENG using single‐walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) as the top electrode,[ 85 ] with a current density of about five times that of ITO based PENG.[ 84 ] The surface of CNT films had a nanosized network with a pore size greater than 100 nm, which favored the growth of ZnO NRs and increased current generation from the PENG. Later they used graphene sheets as transparent electrodes that were synthesized via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) for a fully rollable and transparent PENG.[ 86 ] Vertically aligned ZnO NRs were grown on graphene sheets via low‐temperature hydrothermal technique as described above. The diameter of the ZnO NRs was <100 nm, the length was ≈2 µm and growth density was about 20 µm–2. The PENG produced a j value = 2 µA cm–2 and it was illustrated to be stable and reliable under external loads such as rolling and bending.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the PENG and FE‐SEM image of ZnO NR arrays grown on ITO coated PES substrate (scale bar: 300 nm). Reproduced with permission.[ 84 ] Copyright 2009, Wiley‐VCH.

A five‐layered PENG structure was fabricated by Hu et al., consisting of ZnO NW films on the top and bottom surfaces of flexible polymer substrate and electrodes attached to the ZnO NWs.[ 87 ] When the PENG was strained to 0.12% at a strain rate of 3.56% s–1, the outputs obtained were 10 V and 0.6 µA. It was shown to drive an autonomous wireless system for long‐distance data transmission. Later on, he improved the PENG's performance significantly by pre‐treating ZnO NWs with oxygen plasma, annealing in the presence of air and passivating their surface with specific polymers.[ 88 ] A maximum output of 20 V and 6 µA was achieved from a single layer of NWs, which drove an electronic part without a battery. Zhu et al., grew ZnO NWs selectively on ITO coated silicon substrate followed by spin‐coating a layer of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) to cover them and then deposited aluminum electrodes.[ 89 ] An extremely high output (58 V, 134 µA) was obtained by connecting 9 NGs in parallel. The enhanced output was attributed to the presence of PMMA preventing current leakage in the internal structure. Hu et al. assembled a PENG by dispersing conical‐shaped ZnO NWs onto a flat PMMA film.[ 90 ] Upon mechanical deformation, the conical NWs generated macroscopic piezo potential along with its thickness. Under a compressive strain of 0.11% at a 3.67% s–1 strain rate, the PENG yielded an output of 2 V and 50 nA, which was sufficient to operate an liquid crystal display (LCD) screen.

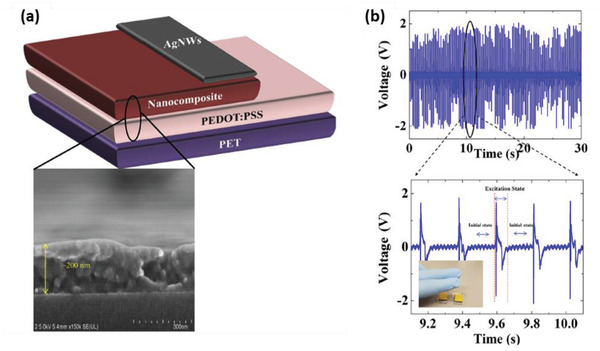

Briscoe et al. fabricated a ZnO NR/poly(3,4‐ethylenedioxythiophene): poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT: PSS) diode on an ITO coated polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate.[ 91, 92 ] A p‐n junction was created between the p‐type polymer, PEDOT: PSS, and n‐type ZnO. The NRs had an aspect ratio of ≈20:1 and formed a dense array. The device had a low energy conversion efficiency (η = 0.0067%) at a maximum bending rate of 500 mm min–1. Later, Jalali et al. used a p‐type copper thiocyanate (CuSCN) as the passivating film on the surface of ZnO NRs and modified the device structure to improve the energy density of the NG by a factor of 10.[ 93 ] The PENG produced a peak open‐circuit voltage (V oc) of 1.07 V with a corresponding power density of 434 µW cm–2 at a release acceleration of 50 g.

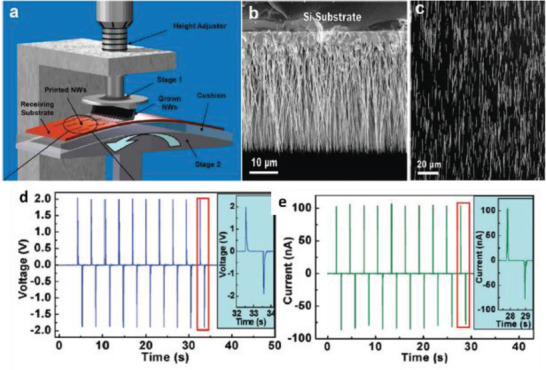

Xu et al., synthesized ZnO NWs aligned parallel to the substrate using a lithographic masking technique involving a series of complicated steps.[ 94 ] First, a seed layer was deposited by covering ZnO stripes partially with a chromium layer. This was followed by growing ZnO NW arrays via the solvent chemical method at 80 °C for 12 h. The PENG comprising of seven hundred rows of ZnO NWs, generated a peak V oc of 1.26 V and I sc of 26 nA at a 2.13% s–1 strain rate. This was much higher compared to a V oc of 100 mV reported from a PENG oriented vertically in the same article. Later, Zhu et al. utilized a simple approach called “sweeping‐printing‐method,” in which vertically oriented ZnO NWs were relocated to a flexible substrate to form horizontally oriented arrays that were crystallographically aligned.[ 50 ] The vertical ZnO NWs were grown on Si substrate and mounted on stage 1 as shown in Figure 6a. They were then separated from the Si substrate and oriented on the host substrate due to the shear force applied by sweeping. The vertical NWs are shown in Figure 6b and the as‐transferred NWs are shown in Figure 6c. The flexible PENG produced a V oc of 2.03 V, I sc of 107 nA, and a corresponding power density of ≈11 mW cm–3 when bent (Figure 6d,e).

Figure 6.

a) Experimental setup for transferring vertically grown ZnO NWs to a flexible substrate to make horizontally aligned ZnO NW arrays. b) SEM image of vertically aligned ZnO NWs grown on Si substrate by a physical vapor deposition method. c) SEM image of the as‐transferred horizontal ZnO NWs on a flexible substrate. d) V oc and e) I sc measured from the PENG at a strain of 0.1% and a strain rate of 5% s–1 with a deformation frequency of 0.33 Hz. The insets are an enlarged view of the boxed area for one cycle of deformation. Reproduced with permission.[ 50 ] Copyright 2010, American Chemical Society.

All the flexible devices described so far were fabricated on plastic substrates like PES, PET, Kapton film. Qin et al. presented a piezoelectric device with ZnO NWs grown radially on Kevlar fiber using a hydrothermal approach.[ 95 ] A coating of tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) was used as a binding agent to attach the ZnO NWs to the fiber surface and each other. The ZnO NWs were single crystalline with diameters ranging between 50–200 nm and characteristic lengths of 3.5 µm. Two fibers, one with 300 nm Au coating and the other as grown were entangled and electricity was generated by brushing the NWs with respect to each other. The textile fiber‐based NG was able to produce a V oc of 1 mV and a very low current of 5 pA due to a large loss in the fiber because of immensely high inner resistance. Similarly, Bai et al., developed a woven NG using two types of fibers—one with ZnO NWs and the other with Pd coated ZnO NWs.[ 96 ] However, this also yielded a poor short circuit current of 17 pA due to the same reason mentioned above.

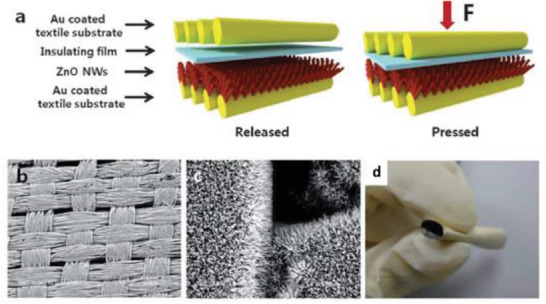

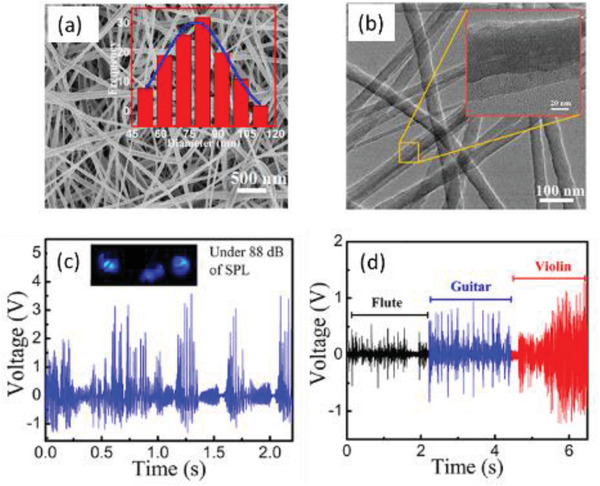

Eventually, Qiu et al. proposed an ultra‐high flexible NG by growing ZnO NRs on a paper substrate.[ 97 ] A small output of 10 mV and 10 nA was generated by the NG and it was demonstrated that electric output could be improved by increasing the device size. Similar work on paper substrates was reported by Lei et al., afterward.[ 28 ] Kim et al. illustrated a hybrid NG on a woven textile substrate by the integration of a dielectric layer and ZnO NWs in between textile substrates as shown in Figure 7a.[ 98 ] The ZnO NWs were uniformly grown on the textile substrate as shown by SEM images in Figure 7b,c. Figure 7d demonstrates excellent flexibility of the rolled textile substrate. The textile‐based NG yielded an improved output voltage of 8 V and a current of 2.5 µA by utilizing sonic waves of 100 dB at 100 Hz as input. The higher output was ascribed to the synergistic piezoelectric effect of ZnO NWs and electrostatic effect of a dielectric film on the textile substrate.

Figure 7.

a) Schematic diagram of the textile‐based hybrid NG. b,c) Large‐area SEM images of ZnO NWs grown on textile substrate. d) Photographic image of textile substrate post rolling. Adapted with permission.[ 98 ] Copyright 2012, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Tamvakos et al., grew large arrays of ZnO NRs with high aspect ratio and excellent crystallinity by template‐free electrochemical deposition approach.[ 99 ] The mean value of the d33 coefficient measured over many individual NRs was 11.8 pC N–1, which is ≈18% higher than 9.93 pC N–1 measured for ZnO bulk material.[ 100, 101, 102 ] The d33 value was higher by a factor ranging between 28–167%, compared to ZnO nanostructures synthesized by the aqueous chemical method,[ 103 ] hydrothermal,[ 104 ] and template‐assisted vapor deposition.[ 105 ]

The literature suggests that the hydrothermal process using an aqueous solution of Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and HMTA has been most commonly used for synthesizing ZnO NWs. The other synthesis methods included thermal vapor deposition, physical vapor deposition, and template‐free electrochemical deposition. The length of ZnO NWs was in the range of 1–500 µm and their diameter between 50–300 nm. Poling treatment was not done in any of the research reported. The highest output voltage of 58 V and current of 134 µA was obtained by connecting nine PENGs in parallel upon punching by human palm.[ 89 ]

3.2. 2D ZnO Nanostructures

This section briefly discusses the piezoelectric properties and energy harvesting capabilities of 2D ZnO nanostructures such as nanosheets and nanowalls, combined with reported synthesis techniques along with PENG fabrication methods.

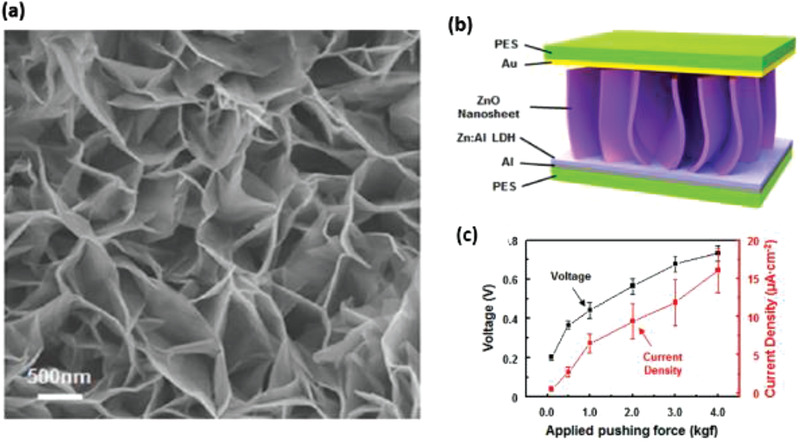

Kim et al., illustrated the use of 2D ZnO nanosheets and an anionic nanoclay layer on an aluminum (Al) electrode to generate piezoelectric power.[ 106 ] The ZnO nanosheet/anionic layer network was synthesized via an aqueous solution of zinc nitrate—HMT at 95 °C and their surface morphology was uneven as shown in Figure 8a. The PENG was constructed by using gold plated PES as a top electrode, Al coated PES as bottom electrode and sandwiching the ZnO nanosheet network/anionic nanoclay heterojunction between them. Figure 8b displays a schematic of the PENG; the layered double hydroxide acted as an anionic nanoclay in this work. The voltage and current density obtained from the PENG was ≈0.7 V and 17 µA cm–2 when a compressive force of 4 kgf was applied (Figure 8c). It was proposed that the combined effect of deformation behavior in ZnO nanosheets, coupled semiconducting and piezoelectric properties of ZnO and self‐formation of anionic nanoclay layer was responsible for power generation. Gupta et al. synthesized ZnO nanosheets by doping ZnO NRs with vanadium for application in DC powered PENG.[ 107 ] It generated an output j ≈ 1.0 µA cm–2 when the same value of compressive force was applied.

Figure 8.

a) FE‐SEM image of the ZnO nanosheets network grown on Al. b) Schematic image of 2D ZnO nanosheet‐based NG. c) Output voltage and current density of the NG obtained by varying the applied pushing force. Reproduced with permission.[ 106 ] Copyright 2013, Springer Nature.

The synthesis of ZnO nanowall and nanowall‐nanowire hybrid structure on a graphene substrate was reported by Kumar et al. using CVD at 900 °C by precisely controlling the thickness of Au catalyst.[ 108 ] Despite the higher sheet resistance of graphene (400 Ω) compared to ITO (60 Ω),[ 85, 86 ] the hybrid nanowall‐nanowire NG generated a DC output voltage of 20 mV and j ≈ 500 nA cm–2 on applying 0.5 kgf compression force. Saravanakumar and Kim assembled a PENG consisting of a ZnO nanowall structure on two surfaces of the PMMA coated flexible substrate.[ 109 ] The nanowall had a wall thickness of 60–80 nm, length of about 2–3 µm and showed a higher response to UV light due to vacancies being present in the nanowall structure. The PENG produced a maximum of 2.5 V output voltage and 80 nA current when deformed by a human finger.

Fortunato et al. compared the piezoelectric properties of ZnO‐NRs vertically grown over ITO substrate and ZnO nanowalls over the aluminum substrate.[ 110 ] Both nanostructures were synthesized via chemical bath deposition. The obtained d33 values were 7.01 ± 0.33 pC N–1 for ZnO‐NRs and 2.63 ± 0.49 pC N–1 for ZnO nanowall films, indicating better piezoelectric properties of NRs compared to nanowalls. This was due to better orientation along the c‐axis and a lower defect rate of ZnO NRs compared to nanowalls.

From the discussed literature in this section, it can be inferred that 2D ZnO nanostructures exhibit lower piezoelectric outputs compared to 1D ZnO nanostructures. A maximum output of 2.5 V and 80 nA was generated by a PENG built using ZnO nanowalls when folded by a human finger.[ 109 ] The synthesis methods of these 2D nanostructures were hydrothermal process using an aqueous solution of Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and HMTA and CVD without any poling treatment.

3.3. Nanostructures of Other Piezoelectric Materials

This section focuses on other nanostructured piezoelectric materials like PZT and PMN‐PT. Analogous to Sections 3.1 and 3.2, we review their synthesis methods, piezoelectric properties, fabrication techniques of PENGs along with their energy harvesting performance.

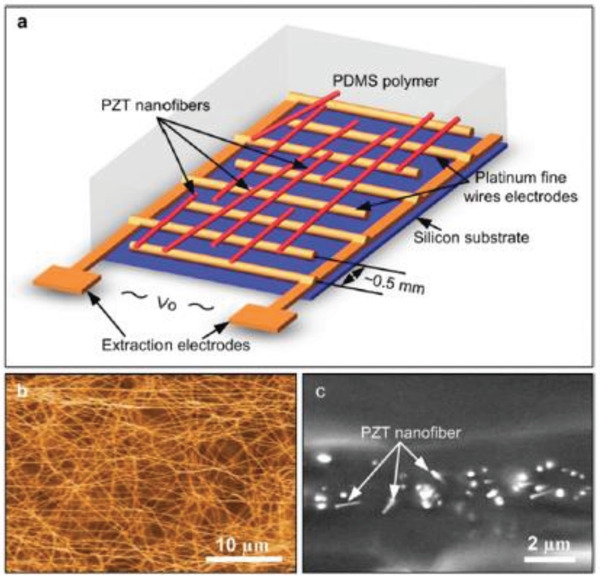

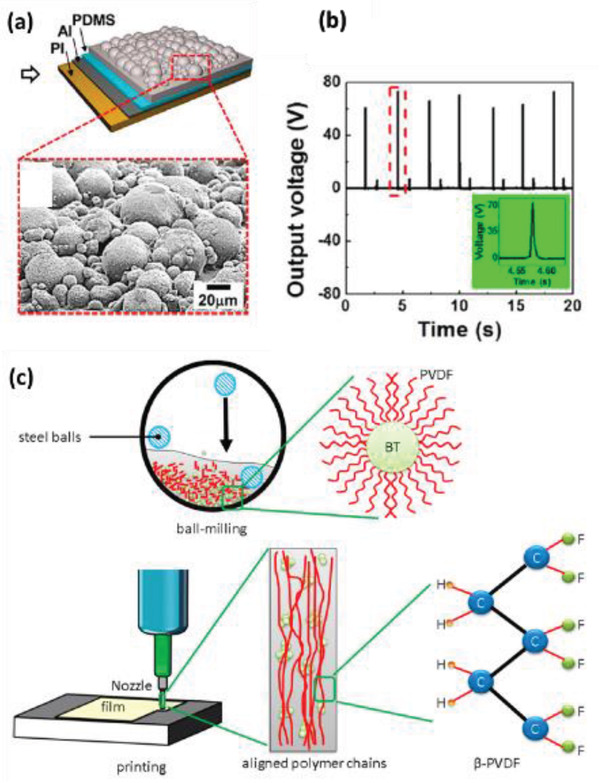

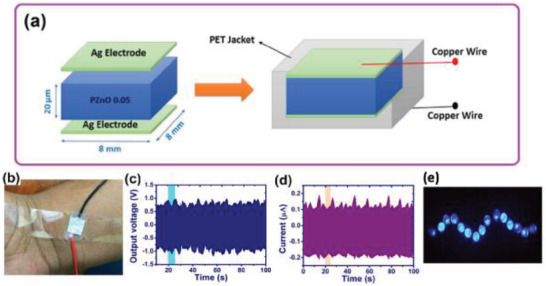

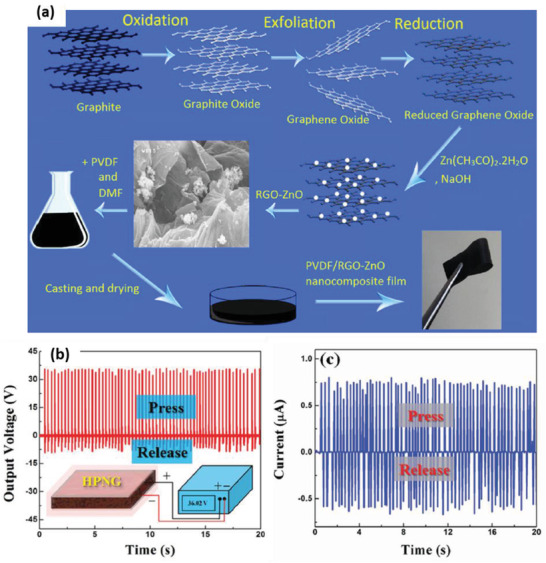

Lead zirconate titanate (PbZr0.5Ti0.5O3), commonly known as PZT is a well‐known piezoelectric material due to its high d33 coefficient of 500–600 pC N–1,[ 111, 112, 113, 114, 115 ] which helps in generating much higher outputs compared to ZnO based materials. PZT nanofibers synthesized by electrospinning display high flexibility, mechanical strength and piezoelectric voltage constant (g33 = 0.079 Vm N–1)[ 116 ] compared to the bulk, thin films or microfibers. In the electrospinning process, high voltage is applied to generate an electrically charged jet of precursor solution, which is squeezed through a small diameter needle and deposited on a collecting plate.[ 117 ] Chen et al. electrospun PZT nanofibers of ≈500 µm length and 60 nm diameter by blending polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) in the PZT precursor solution (Figure 9b).[ 118 ] Subsequently, PVP was removed by annealing the PZT/PVP fibers at 650 °C to obtain a pure perovskite phase of PZT. The PENG was integrated by depositing electrospun PZT nanofibers on interdigitated platinum electrodes set up on a silicon substrate and then enclosing it in soft PDMS matrix (Figure 9a,c). Then, poling was done by applying an electric field of 4 V µm–1 for 24 h at a temperature above 140 °C. The PENG was tested extensively across a wide range of loads and excitation frequencies. It generated a peak output voltage and power of 1.63 V and 0.03 µW, respectively, across a load resistance of 6 MΩ.

Figure 9.

a) Schematic of the PZT nanofiber NG, b) SEM image of the electrospun PZT nanofibers. c) Cross‐sectional SEM image of the PZT nanofibers embedded in PDMS matrix. Reproduced with permission.[ 118 ] Copyright 2010, American Chemical Society.

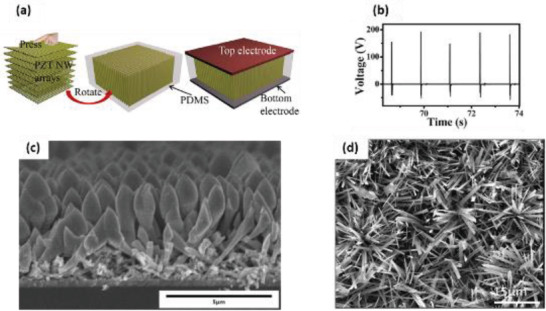

Electrospun PZT nanofiber arrays were produced by Wu et al. from PZT/PVP on multiple rows of parallel electrodes.[ 119 ] The power density of the flexible NG was 200 µW cm–3 and it yielded a maximum V oc of 6 V and I sc of 45 nA when stretched. The generated power was sufficient to illuminate a LCD. Cui et al. placed electro spun PZT NWs onto magnetite (Fe3O4), connected them with silver electrodes and packaged them with PDMS to assemble a contactless NG.[ 115 ] The NWs were deformed with the help of a magnet, generating a maximum current of 50 nA, the voltage of 3.2 V, corresponding to a power density of 170 µW cm–3. Gu et al., built an NG using arrays of electrospun PZT NWs cut from a film, rotating them by 90° and stacking several layers perpendicular to the substrate (Figure 10a).[ 120 ] A very high peak voltage of 209 V and j = 23.5 µA cm–2 was achieved under 0.53 MPa impact pressure (Figure 10b), much higher than previously reported values.[ 89 ] Vertically aligned PZT NWs were also grown hydrothermally using polymer surfactants on titanium oxide[ 121 ] and conductive Nb‐doped SrTiO3 substrates.[ 51 ] The PZT NWs were grown epitaxially at 230 °C. A mono‐layer of PZT NWs were utilized to build the NG and it generated a peak V oc of ≈0.7 V, j ≈ 4 µA cm–2 and power density of 2.8 mW cm–3 on applying impact force.[ 51 ] No et al. synthesized ZnO NWs via hydrothermal process and then deposited PZT thin films on them by magnetron sputtering.[ 122 ] The ZnO/PZT heterojunction structure (Figure 10c) was subjected to corona poling at 11 kV for 30 min. The NG revealed an improved current of 270 nA, compared to 0.5 nA from NG with only ZnO and 9 nA with the only PZT due to synergistic piezoelectric effects of both PZT and ZnO NWs.

Figure 10.

a) The fabrication process of the NG using oriented electrospun nanofibers. b) The output voltage of the NG under a periodic pressure of 0.53 MPa. a,b) Reproduced with permission.[ 120 ] Copyright 2012, American Chemical Society. c) SEM image showing the hetero‐junction structure of ZnO NWs/PZT. Reproduced with permission.[ 122 ] Copyright 2013, Elsevier B.V. d) SEM image of PMN‐PT nanowires. Reproduced with permission.[ 123 ] Copyright 2012, American Chemical Society.

Xu et al., synthesized 0.72Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3‐0.28PbTiO3 (PMN‐PT) nanowires via the hydrothermal method and reported an extremely high d33 value of 381 pCN–1 without poling.[ 123 ] The morphology of PMN‐PT NWs consisted of wire‐like nanostructures with typical lengths between 200 and 800 nm as shown in Figure 10d. The width of these NWs was about 400 nm.

Manganese (Mn) doped (Na0.5K0.5)NbO3 (NKN) electrospun nanofibers were produced by Kang et al. utilizing acetic acid as a chelating agent at an annealing temperature of 750 °C.[ 124 ] The 3 mol% Mn‐doped NKN nanofibers exhibited an enhanced d33 value of 40.06 pC N–1, which is five times greater than un‐doped nanofibers. The doped nanofibers were relocated to a PDMS coated PES substrate with interdigitated Pt electrodes to assemble the flexible PENG. Under bending strain, the PENG displayed an output performance of ≈0.3 V voltage and ≈50 nA current.

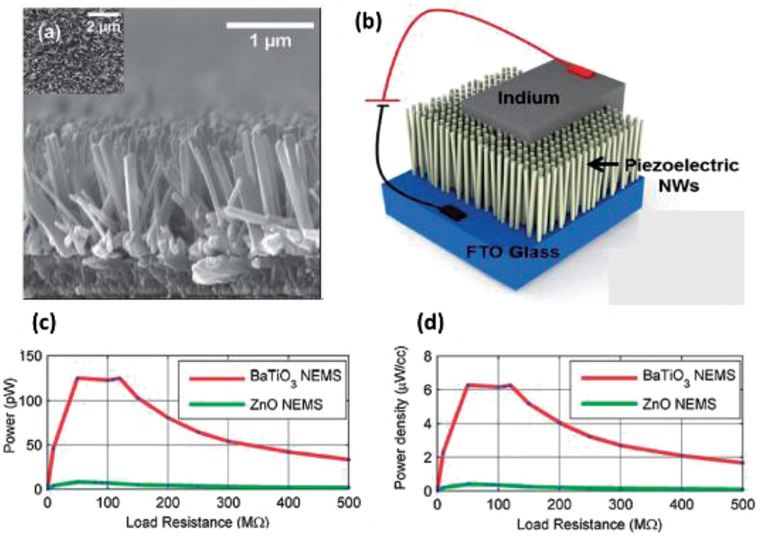

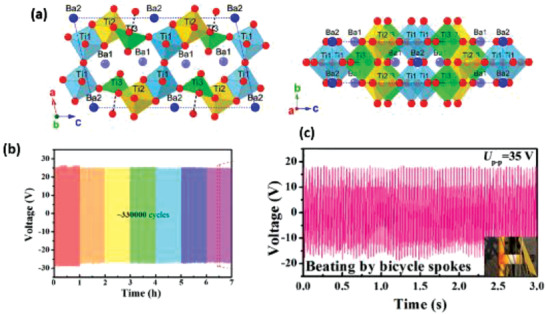

BaTiO3 nanostructures have also been commonly used for energy harvesting applications. The piezoelectric strain constant, d33, of BaTiO3 is ≈90 pC N–1.[ 125 ] Koka et al., produced vertically aligned BaTiO3 NWs of ≈1 µm length via hydrothermal process on conductive fluorine‐doped tin oxide (FTO) substrate (Figure 11a).[ 126 ] The PEH was fabricated by using indium as the top electrode, FTO as the bottom electrode and BaTiO3 NW arrays were sandwiched between them as shown in Figure 11b. After that, it was poled by applying a high electric field of ≈120 kV cm–1 for 24 h. Peak power of ≈125.5 pW and power density of 6.27 µW cm–3 was generated by accelerating the PENG to 1 g at a load resistance of 120 MΩ (Figure 11c,d). This was nearly 16 times greater than ZnO NW based PENG reported in the same work. The enhanced performance was attributed to the larger electromechanical coupling coefficients of BaTiO3 in comparison to ZnO. Later on, the same group reported the growth of ultra‐long (up to 45 µm) BaTiO3 NWs on oxidized Ti substrate using a two‐step hydrothermal process.[ 127 ] Sodium titanate NW arrays were first grown as precursors followed by converting them to BaTiO3 NW arrays as a result of their active ion exchanging property. The BaTiO3 NWs were placed on a conductive glass substrate using a Ti foil coated with PEDOT: PSS as the top electrode to construct an energy harvester. At 0.25 g acceleration, a large peak‐to‐peak voltage (Vp‐p) of 345 mV was obtained from the PENG due to the ultra‐long BaTiO3 NWs.

Figure 11.

a) Cross‐sectional SEM image of the as‐synthesized BaTiO3 NW arrays with inset showing the top view. b) Schematic of the energy harvester constructed using BaTiO3 NW arrays. c) Power and d) power density of the BaTiO3 NW based PEH at various load resistances displaying a peak power of ≈125.5 pW and a peak power density of ≈6.27 µW cm–3 at an optimal resistance of 120 MΩ from 1 g acceleration. These peak power levels are much greater than the peak power from ZnO NW based PEH. Reproduced with permission.[ 126 ] Copyright 2014, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Liu et al., constructed a flexible PENG based on 0.93(Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3‐0.07BaTiO3 (NBT‐0.07BT) nanofibers, synthesized by sol–gel electrospinning.[ 128 ] The NBT‐0.07BT nanofibers have a perovskite structure with a d33 value up to ≈109 pC N–1 for a single NBT‐0.07BT nanofiber. When the dynamic load was applied using a human finger, the PENG produced a V oc of ≈30 V and I SC ≈ 80 nA, which powered a commercial LED.

Energy harvesting using gallium nitride (GaN) nanostructures has also been reported.[ 129, 130, 131 ] Gogneau et al., studied the piezoelectric properties of GaN NWs synthesized via plasma‐assisted molecular beam epitaxy.[ 130 ] When external deformation was applied to the NWs via AFM, Schottky contact was generated between the AFM‐tip and GaN NWs that was inversed with respect to the ZnO NW system.[ 132 ] This showed that the piezoelectricity generation mechanism is dependent on the structural characteristics of the NWs. Jamond et al., synthesized a vertical array of GaN NWs that yielded a maximum voltage of 350 mV and a mean of 228 mV per NW, with a power density of ≈12.7 mW cm–3.[ 131 ] The mechanism of energy generation in both cases was the same as proposed for ZnO NWs.[ 73, 74, 132, 133 ]

Based on discussed literature in this section, it can be summarized that the dominant synthesis methods for PZT, BaTiO3, PMN‐PT are electrospinning, hydrothermal processing and plasma‐assisted molecular beam epitaxy. Except for PMN‐PT NWs, poling was done on all materials. The highest d33 value of 500–600 pC N–1 was reported for PZT NWs.[ 118 ] Also, the highest output voltage of 209 V, j = 23.5 µAcm–2 was obtained from PZT NWs based PENG under stress of 0.53 MPa.[ 120 ] Table 1 summarizes the works on piezoelectric nanostructured materials for energy harvesting applications.

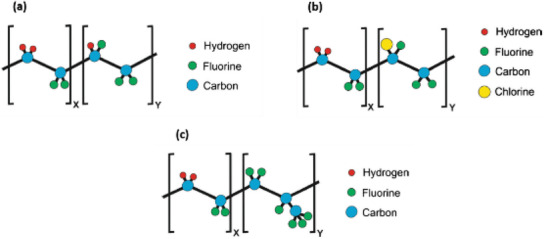

4. Piezoelectric Polymers

Polymers are carbon‐based materials that exhibit a piezoelectric effect because of their molecular structure and orientation. They are much softer than ceramics and display moderate values of strain coefficients (d33) and voltage coefficients (g33). However, their unique properties such as, design flexibility, low density, and simple processing make them appropriate for various energy harvesting applications. Polymers with semi‐crystalline structure have microscopic crystals randomly distributed within an amorphous bulk. These include PVDF,[ 134 ] polyvinylidene fluoride‐trifluoro ethylene P(VDF‐TrFE),[ 135 ] liquid crystal polymers,[ 136 ] polyamides,[ 137 ] cellulose and its derivatives,[ 138, 163, 166 ] parylene C,[ 60 ] PLA,[ 139 ] etc. Piezoelectricity is observed in amorphous or non‐crystalline polymers when its molecular structure contains dipoles. The dipoles are aligned by poling at temperatures higher than the polymer's glass transition temperature (T g). Such polymers consist of polyimide,[ 61, 140 ] nylons,[ 141 ] polyurea,[ 142 ] polyurethanes,[ 139 ] etc. Table 2 compares the piezoelectric properties of these polymers. Fukuda[ 139 ] and Ramadan et al.[ 31 ] wrote detailed reviews on the piezoelectric properties of these polymers.

Table 2.

Piezoelectric properties of polymers

| Polymer | Piezoelectric coefficients dij [pC N–1] | Electromechanical coupling coefficients | Relative Permittivity [ε r] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d33 | d31 | d14 | k33 | k31 | ||

| PVDF | −24 to −34[ 143 ] |

8–22[ 144 ] 60[ 145 ] |

– | 0.2[ 146 ] | 0.12[ 136 ] | 6–12[ 147 ] |

| P(VDF‐TrFE) | 24 to 40[ 148, 149 ] | 12[ 150 ] to 25[ 148 ] | – | 0.29[ 146 ] | 0.16[ 142 ] | 18[ 151 ] |

| P(VDF‐CTFE) | 140[ 152 ] | – | – | 0.36[ 153 ] | – | 13[ 154 ] |

| P(VDF‐HFP) | 24[ 155 ] | 30[ 156 ] to 43[ 157 ] | – | 0.36[ 158 ] | 0.187[ 157 ] | 11[ 158 ] |

| Polyamide 11 | 4[ 159 ] | 14[ 160 ] (at 100–200 °C) | – | – | 0.049[ 136 ] | 5[ 159 ] |

| Polyimide | 2.5–16.5[ 31 ] | – | – | 0.048–0.15[ 31 ] | – | 4[ 61 ] |

| Polylactic acid (PLA) | – | 1.58[ 161 ] | 9.82[ 142 ] | – | – | 3–4[ 162 ] |

| Cellulose | 5.7 ± 1.2 (cellulose nanofibril)[ 163 ] | 1.88–30.6[ 164 ] | −35–60[ 165, 166 ] | – | – | – |

| Polyurethane | – | 27.2[ 167 ] | – | – | – | 4.8[ 167 ] to 6.8[ 168 ] |

| Polyurea |

19 at 60 °C[ 169 ] 21 at 180 °C[ 169 ] |

10[ 142 ] | – | – | 0.08[ 142 ] | – |

| Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) | – | 2[ 136 ] | – | – | – | – |

| Parylene‐C | 2[ 31 ] | – | – | 0.02[ 31 ] | – | – |

| Liquid crystal polymers | −70[ 65 ] | – | – | – | – | – |

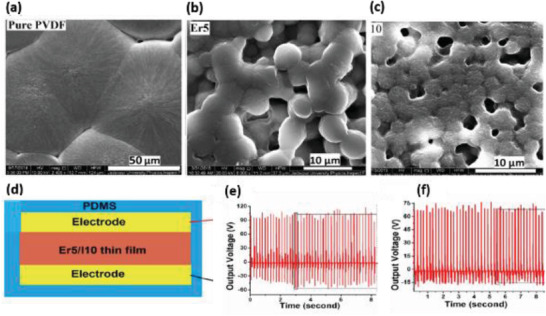

4.1. Polyvinylidene Fluoride Homopolymer

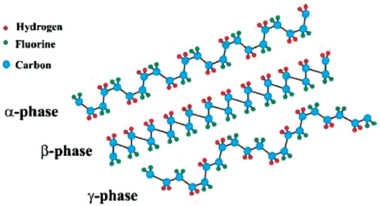

PVDF is a semi‐crystalline, thermoplastic polymer synthesized by the polymerization of vinylidene difluoride (VDF).[ 170, 171, 172, 173 ] Kawai discovered piezoelectricity in PVDF in 1969.[ 141 ] PVDF consists of 3 wt% hydrogens, 59.4 wt% fluorine and exhibits higher piezoelectric coefficients compared to other polymers.[ 154, 174 ] It has 50–70% crystallinity and displays five polymorphs: α, β, γ, δ, and ɛ, although α, β, and γ are seen more frequently.[ 154 ] The larger van der Waals radius of fluorine atoms (1.35 Å) compared to hydrogen atoms (1.2 Å) is the reason behind the existence of polymorphism in PVDF.[ 154 ] The α phase (form II) has a trans‐gauche configuration, in which the polymeric chains are in nonpolar conformation (TGTG′), with alternating H2 and F2 atoms on two sides of the chain (Figure 12).[ 154 ] The polar β phase (form I), has zigzag all‐trans conformation (TTT) of polymeric chains and possesses the maximum dipolar moment per unit cell (8 × 10–30 C m) in comparison to other phases.[ 175 ] The polar γ phase (form III) and δ phase have TTTGTTTG′ and TGTG′ conformations, respectively, that enable PVDF to exhibit piezoelectric properties along with the β phase.[ 134, 176 ] An exhaustive review has been written by Martins et al. on various phases present in PVDF/PVDF copolymers.[ 150 ]

Figure 12.

Schematic representation of the chain conformation for the α, β, and γ phases of PVDF. Reproduced with permission.[ 150 ] Copyright 2014, Elsevier Ltd.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) results have been commonly utilized to evaluate the content of electroactive phases in PVDF. In a sample consisting of α and β‐PVDF, the relative fraction of β‐phase, [F(β)], is given by Beer–Lambert law (Equation (8)).[ 177 ]

| (8) |

where Αα and Αβ are the absorbances of α and β phases at 766 and 840 cm–1; Kα and Kβ are the absorption coefficients at the respective wavenumbers with values of 6.1 × 104 and 7.7 × 104 cm2 mol–1.[ 150 ]

The polar γ phase content in a material containing α and γ phases is given by Equation (9):

| (9) |

where Αα and Αγ are the absorbances of α and γ phases at 762 and 845 cm–1; Kα and Kγ are the absorption coefficients at the respective wavenumbers with values of 0.365 and 0.150 µm–1.[ 178 ]

Among all phases, the β‐phase particularly exhibits exceptional ferroelectric, piezoelectric and pyroelectric properties.[ 179, 180, 181 ] β‐PVDF is usually formed by stretching of the α phase,[ 180, 182, 183 ] melt crystallization under high pressure,[ 184, 185, 186 ] external electric field,[ 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192 ] and fast cooling rates;[ 193 ] from solvent casting,[ 194, 195 ] electrospinning,[ 196, 197 ] and by the addition of different nucleating agents (described in Section 5).

During stretching, the applied stress aligns the PVDF chains, which induces β phase formation. A maximum d31 value of 60 pC N–1 was reported under a poling field of 0.55 MV cm–1, at a temperature of 80 °C and stretching ratio, R, of 4.5 by Kaura et al.[ 145 ] In a similar study done by Salimi and Yousefi, 74% β‐phase was achieved by stretching at 90 °C, for R between 4.5 and 5.[ 180 ] The largest amount of β‐phase and d33 value of 34 pC N–1 for R = 5 at 80 °C was obtained by Gomes et al.[ 143 ] Panigrahi et al., showed a higher piezoelectric response with a poled PVDF device compared to an unpoled one. The PVDF film was prepared via solution casting and the d33 value was reported as −5 pC N–1 after poling at an electric field of 20 kV cm–1.[ 198 ]

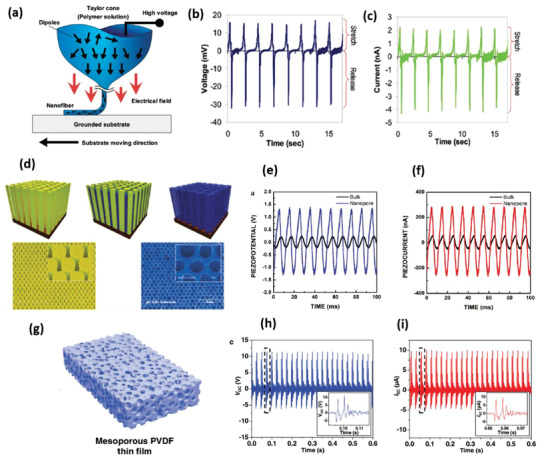

Chang et al. used near field electrospinning (NFES)[ 199, 200 ] in combination with in situ stretching and poling to direct‐write PVDF nanofibers as shown in Figure 13a.[ 201 ] The stretching forces and high electric fields (>107 V m–1) from electrospinning aligned the dipoles in the nanofibers which facilitated α‐β phase transformation. The reported d33 value was −63.25 pC N–1 for single fiber[ 202 ] and −57.6 pC N–1 for PVDF fiber mats,[ 203 ] which is about four times of PVDF films (≈15 pC N–1). The outputs were in the range of 5–30 mV and 0.5–3 nA under stretching and releasing of more than 50 NGs (Figure 13b,c). A peak voltage of 0.2 mV and current of 35 nA was obtained from 500 nanofibers connected in parallel, under repeated mechanical straining.[ 204 ] Liu et al. used a hollow cylindrical NFES process to produce oriented PVDF fibers with a high β phase.[ 205 ] A maximum voltage and current of 76 mV and 39 nA were produced on continuous stretching and releasing the nanofibers at 0.05% strain at 7 Hz frequency. Pan et al. used the same process to fabricate PVDF hollow fibers and obtained a voltage and power of 71.66 mV and 856.07 pW respectively, which was higher than solid PVDF fibers (45.66 mV, 347.61 pW) due to higher elongation and Young's modulus.[ 206 ] Kanik et al. synthesized kilometer long, micro‐and nanoribbons of PVDF based on thermal fiber drawing without electrical poling.[ 207 ] The polar γ phase was obtained due to the combined effect of high temperature and stress applied during the thermal drawing process. The effective d33 value measured from an individual 80 nm thick nanoribbon was −58.5 pC N–1. For energy harvesting and as tapping sensor, two devices were built that displayed a peak voltage of 60 V and a current of 10 µA.

Figure 13.

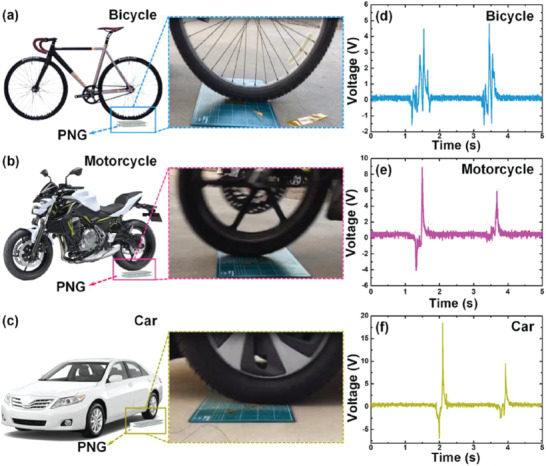

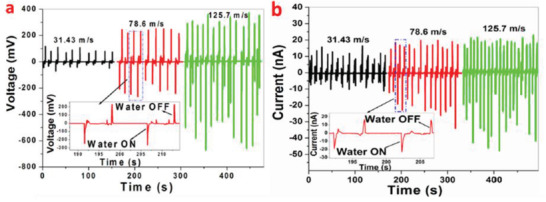

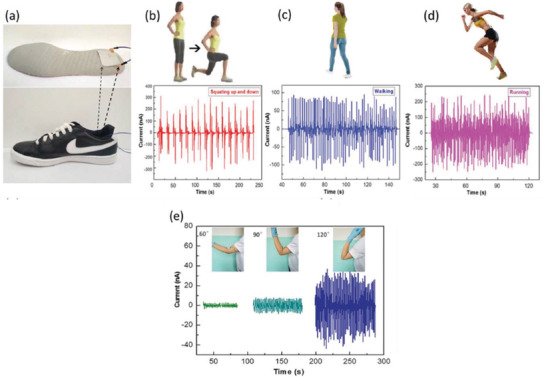

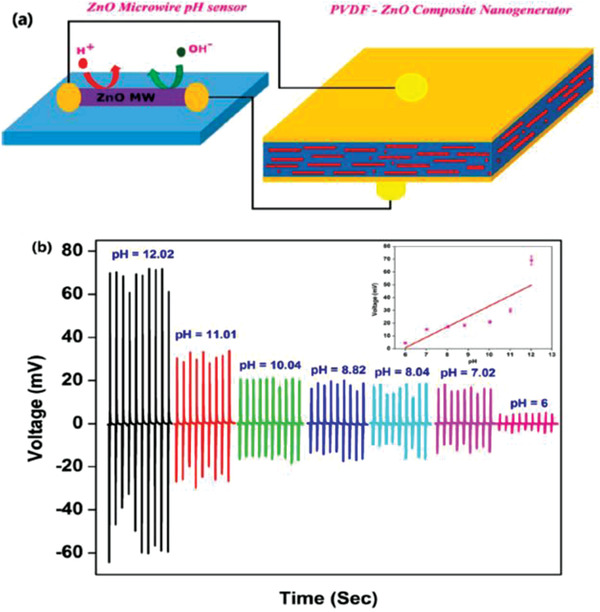

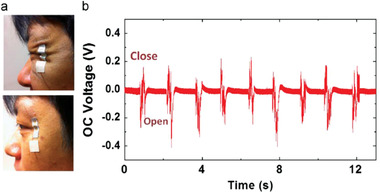

a) Near‐field electrospinning (NFES) to create PVDF nanofibers onto a substrate. b) Output voltage and c) current measured with respect to time under applied strain at 2 Hz. a‐c) Reproduced with permission.[ 201 ] Copyright 2010, American Chemical Society. d) Schematic depiction of PVDF nano porous arrays grown by the template‐assisted method. e) Piezoelectric potential and f) current obtained from porous PVDF and bulk films under the same force. d‐f) Reproduced with permission.[ 208 ] Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society. g) Schematic diagram of mesoporous PVDF film. h) The voltage and i) current output of the PENG under perpetual surface oscillation. Insets show the output curve in the course of one oscillation cycle. g‐i) Reproduced with permission.[ 209 ] Copyright 2014, Wiley‐VCH.