Abstract

Purpose

In this phase I study, we evaluated the safety, biodistribution and dosimetry of [89Zr]Zr-DFO-girentuximab (89Zr-girentuximab) PET/CT imaging in patients with suspicion of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC).

Methods

Ten eligible patients received an intravenous administration of 37 MBq (± 10%) of 89Zr-girentuximab at mass doses of 5 mg or 10 mg. Safety was evaluated according to the NCI CTCAE (version 4.03). Biodistribution and normal organ dosimetry was performed based on PET/CT images acquired at 0.5, 4, 24, 72 and 168 h post-administration. Additionally, tumour dosimetry was performed in patients with confirmed ccRCC and visible tumour uptake on PET/CT imaging.

Results

89Zr-girentuximab was administered in ten patients as per protocol. No treatment-related adverse events ≥ grade 3 were reported. 89Zr-girentuximab imaging allowed successful differentiation between ccRCC and non-ccRCC lesions in all patients, as confirmed with histological data. Dosimetry analysis using OLINDA/EXM 2.1 showed that the organs receiving the highest doses (mean ± SD) were the liver (1.86 ± 0.40 mGy/MBq), the kidneys (1.50 ± 0.22 mGy/MBq) and the heart wall (1.45 ± 0.19 mGy/MBq), with a mean whole body effective dose of 0.57 ± 0.08 mSv/MBq. Tumour dosimetry was performed in the 6 patients with histologically confirmed ccRCC resulting in a median tumour-absorbed dose of 4.03 mGy/MBq (range 1.90–11.6 mGy/MBq).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that 89Zr-girentuximab is safe and well tolerated for the administered activities and mass doses and allows quantitative assessment of 89Zr-girentuximab PET/CT imaging in patients with suspicion of ccRCC.

Trial registration

NCT03556046—14th of June, 2018

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00259-021-05271-w.

Keywords: Organ-based dosimetry, RCC, Girentuximab, Zirconium-89

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for 5% and 3% of all cancers worldwide for men and women, respectively [1]. Renal tumours are diverse and their clinical behaviour is highly dependent on the histological subtype [2]. Of these, clear cell RCC (ccRCC) is the most common subtype and accounts for the majority of kidney cancer-related deaths [3]. The accuracy and generalizability to distinguish ccRCC from non-ccRCC with multiphasic enhanced imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) is debatable [4]. In order to inform patient risk stratification and prevent overtreatment of benign/low-grade lesions, renal tumour biopsies (RTB) are performed. While RTB has demonstrated to be reliable in determining the presence of malignancy, the low negative predictive value remains an issue [5]. Additionally, tumour biopsies are often restricted to a single site and thus fail to provide information on the extent of disease. Therefore, a method to non-invasively identify ccRCC in both primary and metastatic disease provides valuable information. Approximately 95% of all ccRCC have an overexpression of the antigen carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) on the surface of tumour cells due to a mutation of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein [6, 7]. The high expression of CAIX in ccRCC in combination with the very limited expression in normal tissue and non-ccRCC lesions endorses CAIX as an excellent marker for the distinction between ccRCC and non-ccRCC [8]. CAIX can be effectively targeted by the chimeric monoclonal antibody girentuximab [9]. Multiple studies describe the high accuracy and clinical benefit of PET/CT imaging using radiolabeled girentuximab (i.e. [124I]I-girentuximab (124I-girentuximab) and [89Zr]Zr-DFO-girentuximab (89Zr-girentuximab)) compared to CT imaging [10–12]. Furthermore, animal studies demonstrate that 89Zr-girentuximab provides images with better contrast and spatial resolution compared with 124I-girentuximab due to an increased tumour retention of 89Zr [13, 14].

Due to this specific targeting, girentuximab is also considered an excellent carrier for radioimmunotherapy (RIT) in tumours with high CAIX expression including metastasized ccRCC. In studies of single-agent CAIX-targeted RIT with [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-girentuximab (177Lu-girentuximab), a therapeutic response has been demonstrated in patients with pre-treated RCC, with myelotoxicity identified as the most common clinically relevant adverse finding [15, 16]. The use of personalized dosimetry of tumours and organs at risk would allow for a better prediction of the achievable therapeutic value of CAIX-targeted RIT [17]. This could improve patient selection for this treatment and potentially prevent unnecessary toxicity. In order to estimate the biodistribution and radiation dose of girentuximab-bound therapeutic radionuclides, the positron emitter 89Zr could function as an analogue when labeled to the same antibody in a theranostic approach [18]. However, clinical data on the safety, biodistribution and dosimetry of 89Zr-girentuximab are currently lacking. Therefore, this study aims to assess the safety, biodistribution and dosimetry of 89Zr-girentuximab in ten patients suspicious for ccRCC.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

This single-centre, prospective phase I study was approved by the Regional Internal Review Board (CMO Arnhem Nijmegen; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03556046). The study had a primary objective of safety and tolerability and secondary objectives of determining the whole body radiation dosimetry of 89Zr-girentuximab in patients with suspected ccRCC. The study was open to patients who provided written informed consent and met the following eligibility criteria: patients with a clinical suspicion of primary ccRCC or with established diagnosis of ccRCC suspected for recurrence or metastasis; at least 50 years old; and life expectancy of at least 6 months. Exclusion criteria included uncontrolled hyperthyroidism; exposure to experimental diagnostic/therapeutic drug or any radiopharmaceutical within 30 days prior to administration of 89Zr-girentuximab; or established renal cell carcinomas of a histological subtype other than ccRCC. A histological specimen was obtained by either biopsy or surgery to formally characterize the tumour.

Synthesis of 89Zr-girentuximab

Conjugation of N-succinyldesferrioxamine-B-tetrafluorphenol (N-SucDf-TFP/DFO) (VU Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) to girentuximab (girentuximab was provided Telix Pharmaceuticals, Melbourne, Australia) was performed as described previously [19]. In short, 3 days before injection, 2 mg of DFO-girentuximab was radiolabeled with 90 MBq of zirconium-89 (Perkin Elmer, The Netherlands). The radiolabeling process was performed at a pH of 7.2. To achieve the desired pH value, oxalic acid, sodium carbonate and HEPES buffer (adjusted to pH 7.3 by use of sodium hydroxide solution) were added. The radiolabeling was carried out during 60 min at room temperature. Next, unbound 89Zr was complexed by the chelator ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) by incubation for 15 min at room temperature. Then the product was purified using gel filtration on a disposable PD10 column. The protein dose was increased to either 5 mg or 10 mg by adding unlabelled girentuximab. Radiochemical purity was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and exceeded 90%. The end product was diluted to a total volume of 10 ml with NaCl 0.9%.

89Zr-girentuximab administration

A single injection of 37 MBq (± 10%) 89Zr-girentuximab was administered intravenously over approximately 2 min. Post-administration (p.a.), the syringe was flushed once using 10 mL NaCl 0.9%. The intravenous line and syringe were measured for residual activity. Patients were monitored for 30 min after injection. Adverse events were graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 4.03). Patients were randomized in a ratio of 1:1 to receive the 89Zr-girentuximab in a mass dose of 5 mg or 10 mg.

Safety assessment

In order to comprehensively characterize safety and tolerability of 89Zr-girentuximab, a set of standard parameters, including physical exam, vital signs, haematology, serum chemistry, urinalysis and 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs) were assessed at predefined time intervals (screening, pre-administration, 24 h p.a. and 8 days (± 1 day) p.a.).

89Zr-girentuximab PET/CT imaging

For the purpose of internal radiation dosimetry, whole body (i.e. base skull to the upper thighs) PET/CT imaging was performed at 5 time points: 0.5, 4, 24, 72 and 168 h p.a. The PET data were acquired on a Siemens Biograph mCT 4/40 scanner (Siemens, Munich, Germany) using list mode and time of flight (ToF) for 6–8 bed positions with 5 min per bed position. The PET images were reconstructed using a 3D ordered subset expectation maximization (OSEM) algorithm with a spatially varying point-spread function and ToF. Image reconstruction was performed with 3 iterations, 21 subsets and a matrix size from 128 × 128 (whole body imaging) to 300 × 300 pixels (tumour imaging). At 72 h and 168 h p.a., additional PET data of the targeted lesion was acquired using 1 bed position for 20 min in list mode using the same settings. PET imaging was preceded by a low-dose CT (ldCT) scan for attenuation correction and anatomical reference. Additionally, a diagnostic contrast-enhanced CT (ceCT) image was acquired within 30 days before treatment for tumour volume measurements.

Dosimetry

Patient imaging data were loaded to QDOSE dosimetry software suite (ABX-CRO Advanced Pharmaceutical Services Forschungsgesellschaft, Dresden, Germany) for processing and analysis. All ldCT images were coregistered using automatic rigid coregistration followed by deformable coregistration. Manual coregistration between PET images and their corresponding ldCT images was performed when necessary.

For safety dosimetry calculation, the following source organs were included: kidneys, liver, spleen, heart content, red marrow and remainder body. The time activity curve (TAC) for these organs was retrieved from each PET/CT image by determining volumes of interest (VOIs) fully containing each organ (except for the red marrow and the remainder body). The activity in the red marrow was estimated by retrieving the activity in the lumbar vertebrae L1–L5, which contain approximately 12.3% of the total red marrow, and extrapolating it to the total red marrow [20]. Source organ and tumour segmentation was performed by manually drawing volumes of interests (VOIs) on either the PET image or its corresponding CT image, copied to other time points, checked and manually adjusted if necessary, in order to retrieve the TACs for all organs and tumour tissue. The TAC of the tracer in the remainder body was determined by a VOI that contained the complete PET field of view.

In order to assess the TACs in the kidneys in patients with renal tumours, the activity in the contralateral healthy kidney was assessed and doubled. In patients with a solitary kidney and a renal tumour, the tumour was excluded from the kidney VOI. The anatomical tumour volumes were segmented on the pre-study diagnostic ceCT for assessment of the tumour masses.

TACs were fitted either to a mono- or bi-exponential function depending on the shape of the curve and the duration of the activity accumulation phase. Subsequently, source organ and tumour lesion TACs were integrated from time 0 min to infinity and divided by the injected activity to obtain time-integrated activity coefficients (TIACs) for all source organs and tumour lesions. The TIAC for the remainder body was calculated using the effective half-life of the radiotracer in the body, followed by subtraction of the TIACs from the other source organs.

The TIACs for the source organs were subsequently entered as an input to OLINDA/EXM 2.1 for dose calculations [21]. Organ masses were not adapted to individual subject organ masses for dose calculations. For the sake of a comparison with studies using OLINDA/EXM 1.1 with other 89Zr-labelled monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), dose calculations were also performed using OLINDA/EXM 1.1.

The tumour-absorbed doses were determined using a spherical model incorporated in OLINDA/EXM 2.1 in which the tumour TIACs and specific tumour masses (obtained from the segmented tumour volumes assuming a tumour density of 1.03 g/cm3) were used as an input. Additionally, extrapolation of the tumour-absorbed doses to the potential therapeutic beta-emitter 177Lu was performed by recalculating the tumour TIACs when replacing the 89Zr physical decay for the physical decay of 177Lu.

Statistical analysis

Absorbed and effective dose estimates were individually calculated for each patient. Subsequently, these data were summarized using descriptive statistics and reported using mean, median and standard deviation (SD).

Results

Patients

Ten patients (68 ± 8 years; range 55 to 77 years; 8 males) were enrolled in the study. Eight patients had a suspicion of a primary renal tumour and two patients had a suspicion of recurrence or metastasis of known ccRCC (Table 1). All patients were eligible for dosimetric analysis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of 10 patients with RCC suspicion

| Patient | Age (y) | Gender (M/F) | Mass dose (mg) | Primary or metastatic lesion | Sites of suspicious lesion(s) and sizea | Type surgery/biopsy | Days between tissue harvest and PET/CT | Positive PET/CT imaging (Y/N) | Pathology outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73 | M | 5 | Primary | Right kidney (31 mm) | PN | 7 | N | No malignancy |

| 2 | 76 | M | 5 | Primary | Left kidney (61 mm) | PN | 21 | Y | ccRCC |

| 3 | 61 | M | 5 | Primary | Left kidney (83 mm) | RN | 28 | Y | ccRCC |

| 4 | 71 | M | 10 | Primary | Right kidney (58 mm) | RN | 70 | Y | ccRCC |

| 5 | 76 | F | 10 | Primary | Right kidney (42 mm) | RN | 63 | N | Papillary RCC |

| 6 | 57 | M | 10 | Metastasis | Left kidney (20 mm), left adrenal gland (23 mm) | N/A | N/A | Yb | ccRCCc |

| 7 | 77 | M | 5 | Primary | Right kidney (49 mm) | Biopsy | 41 | N | Chromophobe RCC |

| 8 | 63 | M | 10 | Primary | Left kidney (35 mm) | PN | 21 | Y | ccRCC |

| 9 | 55 | M | 10 | Primary | Bilateral kidneys (37 and 26 mm) | Biopsy (right) | 63 | N | Papillary RCC |

| 10 | 68 | F | 5 | Metastasis | Right adrenal gland (21 mm) | Adrenalectomy | 101 | Y | ccRCC |

aSize of lesion in the largest diameter (millimetre). b PET/CT imaging showed accumulation of 89Zr-girentuximab in a mediastinal lesion (10 mm) which was not suspect beforehand. c Based on historical pathology results of primary renal tumour in the right kidney. N/A, not applicable; PN, partial nephrectomy; RN, radical nephrectomy

Safety evaluation

The mean administered activity was 36.7 ± 1.1 MBq (range 34.2 to 38.34 MBq) of 89Zr-girentuximab. A total of 7 adverse events (AE) were reported in 4 patients. One SAE, post-operative bleeding (grade 3), was reported but not considered to be related to administration of the investigational product. No adjustment of dosing or administration occurred due to AEs. All remaining AEs were graded as mild and ranged from common cold to nausea (Supplementary Table 1). No significant changes in vital signs, laboratory results or ECGs were observed (data on file).

PET/CT imaging

All PET/CT imaging was evaluated by a single, experienced nuclear medicine physician. The criteria for tumour uptake were binary based on visual assessment. In all patients, 89Zr-girentuximab PET/CT imaging allowed successful differentiation between ccRCC and non-ccRCC lesions which was confirmed with the reference histology specimens.

In six patients (patients 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 10), 89Zr-girentuximab uptake was observed in the suspicious lesion(s). In most patients, tumour lesions became visible on PET imaging at 24 h p.a. after which subjective visualization improved. No additional lesions were detected between ~ 72 and ~ 168 h p.a. in any patient. In patient 8, the tumour lesion was already visible at 0.5 h p.a. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

MIP of patient #8 (male 63 years. Mass dose of 10 mg girentuximab) demonstrating a ccRCC tumour in left kidney (red arrow) at 0.5 h p.a. with an increased tumour to background ratio over time. MIP, maximum intensity projection

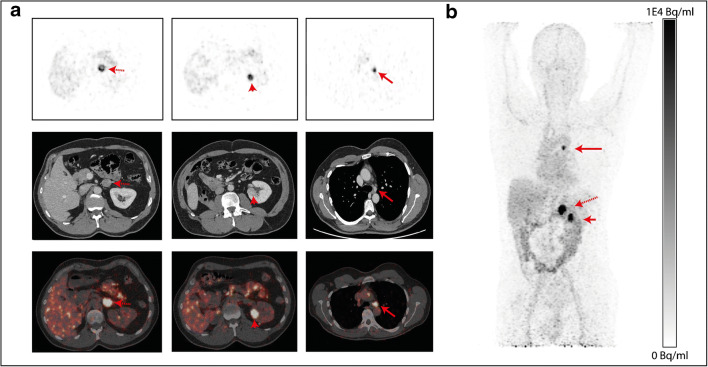

In patient 6, who had a history of ccRCC, three 89Zr-girentuximab-avid lesions were detected in the left kidney, left adrenal gland and mediastinal lymph node, respectively (Fig. 2). Interestingly, of these lesions, only two (left kidney and left adrenal gland) were diagnosed on CT imaging. Even though no histological specimen of the metastases was obtained, follow-up CT imaging demonstrated growth of all three lesions, strongly suggesting metastases. In the remaining patients, all lesions with 89Zr-girentuximab uptake corresponded to the lesions that were deemed suspicious based on ceCT imaging.

Fig. 2.

a PET imaging (168 h p.a.; upper row). ceCT (middle row) and fused imaging (lower row) of patient #6 (male 57 years. Mass dose 10 mg girentuximab) showing 89Zr-girentuximab uptake in the adrenal gland (red dotted arrow). Left kidney (red arrowhead) and mediastinal lymph node (red arrow) from left to right. b The MIP of patient #6 at 168 h p.a.; p.a., post-administration; MIP, maximum intensity projection

No tumour uptake of 89Zr-girentuximab was seen in 4 patients for whom tumour lesions were histologically confirmed as non-ccRCC. In patient 1, the resected specimen showed residual cyst without malignancy; patients 5 and 9 both had confirmed papillary RCC, and patient 7 had confirmed chromophobe RCC.

Radiation dosimetry

The mean absorbed doses when using OLINDA/EXM 2.1 are given in Table 2 (individual dose values calculated with OLINDA/EXM 2.1 and OLINDA/EXM 1.1 can be found in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, respectively). Highest absorbed doses were seen in the liver (1.86 mGy/MBq), kidneys (1.50 mGy/MBq), heart wall (1.45 mGy/MBq), adrenals (1.07 mGy/MBq) and spleen (1.03 mGy/MBq). The mean whole body effective dose following administration of 89Zr-girentuximab was 0.57 ± 0.08 mSv/MBq (range 0.47–0.71 mSv/MBq).

Table 2.

Absorbed dose to individual organs for 89Zr-girentuximab calculated using OLINDA/EXM 2.1

| Target organ | Absorbed dose estimates mGy/MBq | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mg (n = 5) | 10 mg (n = 5) | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

| Adrenals | 1.11 | 0.16 | 0.85 | 1.27 | 1.04 | 0.10 | 0.88 | 1.15 |

| Brain | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.43 |

| Breastsa | 0.46 | – | – | – | 0.47 | – | – | – |

| Oesophagus | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.60 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.08 | 0.60 | 0.80 |

| Eyes | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.43 |

| Gallbladder wall | 1.11 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 1.33 | 0.96 | 0.12 | 0.80 | 1.13 |

| Left colon | 0.62 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.55 | 0.81 |

| Small intestines | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.65 |

| Stomach wall | 0.67 | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.05 | 0.61 | 0.75 |

| Right colon | 0.66 | 0.06 | 0.55 | 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.71 |

| Rectum | 0.51 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.63 |

| Heart wall | 1.40 | 0.22 | 1.16 | 1.66 | 1.50 | 0.20 | 1.30 | 1.82 |

| Kidneys | 1.47 | 0.32 | 1.25 | 2.03 | 1.53 | 0.12 | 1.41 | 1.68 |

| Liver | 2.07 | 0.45 | 1.34 | 2.50 | 1.65 | 0.28 | 1.21 | 1.98 |

| Lungs | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.52 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.53 | 0.71 |

| Ovariesa | 0.61 | – | – | – | 0.65 | – | ||

| Pancreas | 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.64 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 0.10 | 0.66 | 0.90 |

| Prostate | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Salivary glands | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.47 |

| Red marrow | 0.79 | 0.16 | 0.63 | 1.01 | 0.76 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.92 |

| Osteogenic cells | 0.63 | 0.10 | 0.54 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 0.58 | 0.72 |

| Spleen | 1.05 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 1.38 | 1.01 | 0.28 | 0.66 | 1.35 |

| Testes | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.36 |

| Thymus | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.76 |

| Thyroid | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.51 |

| Urinary bladder wall | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

| Uterusa | 0.59 | – | – | – | 0.62 | – | – | – |

| Effective dose in total body (mSv/MBq) | 0.58 | 0.10 | 0.47 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.49 | 0.70 |

aBoth cohorts included one woman; hence, no SD is reported. SD, standard deviation

Tumour dosimetry

Tumour dosimetry was performed in 6 patients with a confirmed ccRCC and visible uptake in the tumour region (Table 3). In all 6 patients, the biological accumulation of 89Zr-girentuximab was still ongoing at the last time point (data on file). Patient 10 had a nephrectomy prior to inclusion in this study and therefore dosimetry was only performed on a metastasis in the right adrenal gland. The absorbed dose for 89Zr-girentuximab in the tumour lesions ranged between 1.90 and 11.6 mGy/MBq with a mean of 4.93 mGy/MBq. The extrapolation to 177Lu resulted in tumour-absorbed doses between 2.77 and 23.6 mGy/MBq (Table 3).

Table 3.

Tumour-absorbed dose for 89Zr-girentuximab

| Patient | Tumour | Nuclear grade | Pathological dedifferentiation (Y/N) | Estimated tumour mass (g) | Absorbed dose 89Zr (mGy/MBq) | Extrapolated absorbed dose 177Lu (mGy/MBq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Primary—left kidney | WHO 2 | N | 81.4 | 2.10 | 3.40 |

| 3 | Primary—left kidney | WHO 4 | Y. 40% sarcomatoid | 253.4 | 1.90 | 2.77 |

| 4 | Primary—right kidney | WHO 3 | N | 114.9 | 3.52 | 6.73 |

| 6 | Primary—left kidney | N/A | N/A | 6.0 | 4.54 | 11.44 |

| 8 | Primary—left kidney | WHO 2 | N | 16.6 | 11.6 | 23.60 |

| 10 | Metastasis—right adrenal gland | N/A | N/A | 6.8 | 5.88 | 14.46 |

| Mean | 77.3 | 4.93 | 10.40 | |||

| SD | 77.4 | 3.29 | 7.22 | |||

| Median | 55.4 | 4.03 | 9.09 |

N/A, not applicable

Discussion

In this phase I study, we demonstrated that intravenously administered 89Zr-girentuximab is safe and facilitates feasible dosimetric analyses in patients with primary and advanced RCC. Additionally, we explored the extrapolation of the tumour doses to a therapeutic radiopharmaceutical (177Lu-girentuximab) using 89Zr-girentuximab as a surrogate.

The mean effective dose of 89Zr-girentuximab (0.57 mSv/MBq) is in range with the reported mean effective doses of other 89Zr-labelled mAbs (0.36–0.66 mSv/MBq), which have been reported for 89Zr-HuJ591, 89Zr-trastuzumab, 89Zr-pertuzumab and 89Zr-cmAb U36 [22–25]. Additionally, the organ-absorbed doses indicate a similar biodistribution to other 89Zr-based mAbs with the liver, kidneys and heart wall receiving the highest doses. Although a quantitative comparison between doses of 5 and 10 mg was not included in the objectives of this study, our data suggest a slight increase of hepatic uptake in the 5 mg group. The mechanism behind this is not fully understood, but could partly be explained by the blocking of non-specific liver binding at higher antibody doses, which is in line with previous preclinical observations [26, 27]. Moreover, a recent clinical study with radiolabeled girentuximab demonstrated that a protein dose of 10 mg granted the highest tumour to normal ratio [28]. Furthermore, we demonstrated that for an administered activity of approximately 37 MBq, image time points ranging from 3 to 7 days p.a. are appropriate for visual assessment of ccRCC lesions. While imaging at day 7 could offer an improved tumour to background ratio, no additional lesions were detected between day 3 and 7 in these patients. Similar findings concerning optimal imaging time have been reported in earlier studies with radiolabeled girentuximab as well as other 89Zr-mAb tracers [22, 25, 29].

The relatively slow uptake and clearance of antibodies requires labeling with radioisotopes that also have a long physical half-life (i.e. 89Zr (t1/2 = 78.4 h) or 124I (t1/2 = 100.2 h)) to achieve optimal imaging. As a result, the radiation burden on the patient when using antibody-based tracers is relatively high in comparison with more rapidly clearing PET tracers such as [18F]FDG [30]. This could be considered a limiting factor in the development of antibody-based tracers and therefore it is paramount to reduce the radiation dose where feasible. This study indicates that the administration of ~ 37 MBq of 89Zr-girentuximab is sufficient to distinguish ccRCC from non-ccRCC lesions. Since the radiation dose is proportional to the administered activity, optimization of the injected radioactivity (i.e. administration of the minimum activity that guarantees sufficient image diagnostic performance) substantially decreases the overall radiation burden on the patient. Furthermore, this study offers valuable safety data on 89Zr-girentuximab administration that is necessary to further progress the clinical implementation of this tracer in ccRCC diagnosis (e.g. differentiation of ccRCC, staging of ccRCC or evaluating response to therapy). In order to assess the diagnostic accuracy of 89Zr-girentuximab in renal masses, the multi-centre phase III ZIRCON study has been initiated (NCT03849118).

Girentuximab-based tracers may also be used for therapeutic purposes (i.e. RIT) either alone or in combination with other agents. RIT is based on the delivery of a high dose of therapeutic radiation to cancer cells through tumour antigen–specific targeting. Although this approach has been investigated for several decades, clinical implementation of RIT in solid tumours remains a challenge. The dose-limiting normal tissue in radioimmunotherapy using β-emitters is usually bone marrow [31], as seen in studies that have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of multiple RIT cycles of 177Lu-girentuximab in metastasized ccRCC. However, grades 3–4 myelotoxicity precluded additional treatment cycles in several patients [15, 16]. In these studies, a predetermined dose of 177Lu-girentuximab was administered to all patients. As a future perspective, PET/CT imaging with 89Zr-girentuximab might be a feasible analogue for individualized treatment planning for RIT with girentuximab in advanced ccRCC, which will become even more important with the increasing interest in RIT with alpha-emitting radionuclides. A dosimetry-based theranostic approach is particularly attractive as it allows for an estimation of dose delivery to tumours and normal tissue, thus can be used to guide the selection of patients who are most likely to benefit from RIT [17, 32].

Conclusion

In the present study, 89Zr-girentuximab was found to be safe and well tolerated by all patients after intravenous administration. In addition, PET imaging with 89Zr-girentuximab allowed successful differentiation between ccRCC and non-ccRCC lesions in all evaluated patients. The mean effective dose of 89Zr-girentuximab was 0.57 mSv/MBq.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 352 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Michael Tapner for participating in the intellectual discussion concerning this study. Additionally, we would like to thank Wencke Lehnert for her work on the dosimetric analysis.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Robin Merkx, Luis David Jimenez, Daphne Lobeek, Mark Konijnenberg and Peter Mulders. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Robin Merkx and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported financially through a clinical fellowship sponsorship agreement between the Radboudumc, Nijmegen, The Netherlands and Telix Pharmaceuticals, Melbourne, Australia.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Regional Internal Review Board (CMO Arnhem Nijmegen) and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Andreas Kluge is Chief Medical Advisor at Telix Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Dosimetry

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Capitanio U, Bensalah K, Bex A, Boorjian SA, Bray F, Coleman J, et al. Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2019;75(1):74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keegan KA, Schupp CW, Chamie K, Hellenthal NJ, Evans CP, Koppie TM. Histopathology of surgically treated renal cell carcinoma: survival differences by subtype and stage. J Urol. 2012;188(2):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saad AM, Gad MM, Al-Husseini MJ, Ruhban IA, Sonbol MB, Ho TH. Trends in renal-cell carcinoma incidence and mortality in the United States in the last 2 decades: a SEER-based study. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2019;17(1):46–57.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JH, Sun HY, Hwang J, Hong SS, Cho YJ, Doo SW, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced computed tomography and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of small renal masses in real practice: sensitivity and specificity according to subjective radiologic interpretation. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14(1):260. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-1017-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez A, Feldman AS, Hakimi AA. Current management of small renal masses, including patient selection, renal tumor biopsy, active surveillance, and thermal ablation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(36):3591–3600. doi: 10.1200/jco.2018.79.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, Yao M, Duh FM, Orcutt ML, et al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science. 1993;260(5112):1317–1320. doi: 10.1126/science.8493574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivanov SV, Kuzmin I, Wei MH, Pack S, Geil L, Johnson BE, et al. Down-regulation of transmembrane carbonic anhydrases in renal cell carcinoma cell lines by wild-type von Hippel-Lindau transgenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(21):12596–12601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grabmaier K, Vissers JL, De Weijert MC, Oosterwijk-Wakka JC, Van Bokhoven A, Brakenhoff RH, et al. Molecular cloning and immunogenicity of renal cell carcinoma-associated antigen G250. Int J Cancer. 2000;85(6):865–870. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000315)85:6<865::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oosterwijk E, Ruiter DJ, Hoedemaeker PJ, Pauwels EK, Jonas U, Zwartendijk J, et al. Monoclonal antibody G 250 recognizes a determinant present in renal-cell carcinoma and absent from normal kidney. Int J Cancer. 1986;38(4):489–494. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910380406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muselaers CH, Boerman OC, Oosterwijk E, Langenhuijsen JF, Oyen WJ, Mulders PF. Indium-111-labeled girentuximab immunoSPECT as a diagnostic tool in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2013;63(6):1101–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Divgi CR, Uzzo RG, Gatsonis C, Bartz R, Treutner S, Yu JQ, et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography identification of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: results from the REDECT trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(2):187–194. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.41.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hekman MCH, Rijpkema M, Aarntzen EH, Mulder SF, Langenhuijsen JF, Oosterwijk E, et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography with (89)Zr-girentuximab can aid in diagnostic dilemmas of clear cell renal cell carcinoma suspicion. Eur Urol. 2018;74(3):257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheal SM, Punzalan B, Doran MG, Evans MJ, Osborne JR, Lewis JS, et al. Pairwise comparison of 89Zr- and 124I-labeled cG250 based on positron emission tomography imaging and nonlinear immunokinetic modeling: in vivo carbonic anhydrase IX receptor binding and internalization in mouse xenografts of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41(5):985–994. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2679-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stillebroer AB, Franssen GM, Mulders PF, Oyen WJ, van Dongen GA, Laverman P, et al. ImmunoPET imaging of renal cell carcinoma with (124)I- and (89)Zr-labeled anti-CAIX monoclonal antibody cG250 in mice. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2013;28(7):510–515. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2013.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muselaers CH, Boers-Sonderen MJ, van Oostenbrugge TJ, Boerman OC, Desar IM, Stillebroer AB, et al. Phase 2 study of lutetium 177-labeled anti-carbonic anhydrase IX monoclonal antibody girentuximab in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2016;69(5):767–770. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stillebroer AB, Boerman OC, Desar IM, Boers-Sonderen MJ, van Herpen CM, Langenhuijsen JF, et al. Phase 1 radioimmunotherapy study with lutetium 177-labeled anti-carbonic anhydrase IX monoclonal antibody girentuximab in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2013;64(3):478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stillebroer AB, Zegers CM, Boerman OC, Oosterwijk E, Mulders PF, O'Donoghue JA, et al. Dosimetric analysis of 177Lu-cG250 radioimmunotherapy in renal cell carcinoma patients: correlation with myelotoxicity and pretherapeutic absorbed dose predictions based on 111In-cG250 imaging. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53(1):82–89. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.094896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perk LR, Visser GW, Vosjan MJ, Stigter-van Walsum M, Tijink BM, Leemans CR, et al. (89)Zr as a PET surrogate radioisotope for scouting biodistribution of the therapeutic radiometals (90)Y and (177)Lu in tumor-bearing nude mice after coupling to the internalizing antibody cetuximab. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46(11):1898–1906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verhoeff SR, van Es SC, Boon E, van Helden E, Angus L, Elias SG, et al. Lesion detection by [(89)Zr]Zr-DFO-girentuximab and [(18)F]FDG-PET/CT in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(9):1931–1939. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04358-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hindorf C, Glatting G, Chiesa C, Linden O, Flux G. EANM Dosimetry committee guidelines for bone marrow and whole-body dosimetry. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(6):1238–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stabin MG, Farmer A. OLINDA/EXM 2.0: The new generation dosimetry modeling code. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53:585. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.106138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandit-Taskar N, O'Donoghue JA, Beylergil V, Lyashchenko S, Ruan S, Solomon SB, et al. (8)(9)Zr-huJ591 immuno-PET imaging in patients with advanced metastatic prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41(11):2093–2105. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2830-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laforest R, Lapi SE, Oyama R, Bose R, Tabchy A, Marquez-Nostra BV, et al. [(89)Zr]Trastuzumab: evaluation of radiation dosimetry, safety, and optimal imaging parameters in women with HER2-positive breast cancer. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2016;18(6):952–959. doi: 10.1007/s11307-016-0951-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulaner GA, Lyashchenko SK, Riedl C, Ruan S, Zanzonico PB, Lake D, et al. First-in-human human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-targeted imaging using (89)Zr-pertuzumab PET/CT: dosimetry and clinical application in patients with breast cancer. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2018;59(6):900–906. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.202010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borjesson PK, Jauw YW, de Bree R, Roos JC, Castelijns JA, Leemans CR, et al. Radiation dosimetry of 89Zr-labeled chimeric monoclonal antibody U36 as used for immuno-PET in head and neck cancer patients. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2009;50(11):1828–1836. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.065862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muselaers CH, Oosterwijk E, Bos DL, Oyen WJ, Mulders PF, Boerman OC. Optimizing lutetium 177-anti-carbonic anhydrase IX radioimmunotherapy in an intraperitoneal clear cell renal cell carcinoma xenograft model. Mol Imaging. 2014;13:1–7. doi: 10.2310/7290.2014.00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyle CC, Paine AJ, Mather SJ. The mechanism of hepatic uptake of a radiolabelled monoclonal antibody. Int J Cancer. 1992;50(6):912–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910500616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hekman MC, Rijpkema M, Muselaers CH, Oosterwijk E, Hulsbergen-Van de Kaa CA, Boerman OC, et al. Tumor-targeted dual-modality imaging to improve intraoperative visualization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a first in man study. Theranostics. 2018;8(8):2161–2170. doi: 10.7150/thno.23335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Donoghue JA, Lewis JS, Pandit-Taskar N, Fleming SE, Schoder H, Larson SM, et al. Pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and radiation dosimetry for (89)Zr-trastuzumab in patients with esophagogastric cancer. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2018;59(1):161–166. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.194555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinn B, Dauer Z, Pandit-Taskar N, Schoder H, Dauer LT. Radiation dosimetry of 18F-FDG PET/CT: incorporating exam-specific parameters in dose estimates. BMC Med Imaging. 2016;16(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12880-016-0143-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vallabhajosula S, Goldsmith SJ, Kostakoglu L, Milowsky MI, Nanus DM, Bander NH. Radioimmunotherapy of prostate cancer using 90Y- and 177Lu-labeled J591 monoclonal antibodies: effect of multiple treatments on myelotoxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(19 Pt 2):7195s–7200s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-1004-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verel I, Visser GW, van Dongen GA. The promise of immuno-PET in radioimmunotherapy. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46 Suppl 1:164s–171s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 352 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.