Abstract

During V(D)J recombination two proteins, RAG1 and RAG2, assemble as a protein-DNA complex with the appropriate DNA targets containing recombination signal sequences (RSSs). The properties of this complex require a fairly elaborate set of protein-protein and protein-DNA contacts. Here we show that a purified derivative of RAG1, without DNA, exists predominantly as a homodimer. A RAG2 derivative alone has monomer, dimer, and larger forms. The coexpressed RAG1 and RAG2 proteins form a mixed tetramer in solution which contains two molecules of each protein. The same tetramer of RAG1 and RAG2 plus one DNA molecule is the form active in cleavage. Additionally, we show that both DNA products following cleavage can still be held together in a stable protein-DNA complex.

A site-specific DNA recombination mechanism, termed V(D)J recombination, is used in the developing adaptive immune system to assemble active rearranged genes for the antigen receptors from arrays of inherited inactive segments (reviewed in references 6 and 11). Targets for this recombination reaction are identified by recombination signal sequences (RSSs) which specify the recombination site in the DNA immediately adjacent to the coding sequences. The RSS is composed of a conserved heptamer (CACAGTG) and nonamer (ACAAAAACC) motif, separated by a spacer of either 12 or 23 bp in length (called 12RSS or 23RSS, respectively). A productive rearrangement in cells always occurs between pairs of DNA segments bordered by RSS elements of the two different spacer lengths (the 12/23 rule [26]). Within a chromosomal locus, similar segments generally carry RSSs of the same length. Owing to the 12/23 rule, this organization permits a V segment (for example) to join to a D segment but not a second V segment. Several recent investigations have shown that binding to individual DNA molecules containing single RSS as well as simultaneous binding that obeys the 12/23 rule can be mediated by RAG1 and RAG2 (5, 7, 8, 30, 31) and is aided by the sequence-nonspecific DNA bending protein HMG1 (9, 21, 27). Invariably, these studies have analyzed the behavior of the RAG proteins as part of a DNA-protein complex. Since we and others have shown that the RAG proteins can bind DNA in specific and nonspecific manners (1, 15, 25), it was not initially clear to us whether protein-protein interactions independent of protein-DNA interactions play a role in the complex formation. For example, in the most extreme case, each protein could be present in the complex purely through its contact with DNA. We undertook this study from the perspective that a description of the simpler protein-protein interactions and stoichiometries with and without single RSS-containing DNA molecules would give us a better understanding of the components available for future studies of the more complicated structure containing two RSSs.

The DNA recombination occurs through a cutting and pasting mechanism in which specific double-strand breaks are generated adjacent to each RSS (13). This cleavage reaction occurs in two steps. First, one DNA strand is nicked at the coding sequence bordering the heptamer. This nick is then converted to a double-strand break in a second step that leaves the so-called signal end as blunt duplex DNA and the coding end as an unusual DNA hairpin (13). Since the coding DNA is no longer covalently bound to the RSS, it remains something of a mystery as to how the two coding ends are held in proximity during the interval of processing before they are ultimately joined together. The cleaved coding end has been found retained within a synaptic complex (7), and we report here that the coding end liberated by DNA cleavage of a single RSS is retained by a complex containing the RAG proteins.

Central to the cleavage steps are the two proteins RAG1 and RAG2 (16, 22). Most significantly, these two proteins are sufficient to reconstitute site-specific cleavage of DNA substrates in vitro. It appears that the two proteins cooperate at every stage for which an activity can be measured. While DNA binding can be demonstrated for RAG1 (4, 23) and weakly for RAG2 (15), the specificity of binding for the RSS is enhanced when both proteins are present simultaneously (1, 15, 25). Furthermore, nicking and hairpin formation on either duplex DNA substrates or prenicked substrates proceeds only in the presence of both proteins (13, 28, 29), and hairpin opening may also be mediated by both proteins (2).

Coupled cleavage of substrates that contain the correct pair of RSS elements can also be observed with RAG1 and RAG2, as demonstrated with purified proteins (30), and with cell extracts (5), though it is enhanced by the additional presence of the DNA bending protein HMG1 (27). The cleavage activities show a dependence on divalent cations. Cleavage of individual RSS-containing oligonucleotides is obtained only in the presence of manganese, while coupled cleavage can be obtained with the more physiologic magnesium ion. The behavior of coupled cleavage supports the existence of a biochemical intermediate in which both RSSs are bound prior to either being cleaved. Two RSS elements can be bound simultaneously by RAG1 and RAG2 in a manner that follows the 12/23 rule (7). This synaptic structure is similar in principle to reaction intermediates already studied in greater detail during bacterial recombination and transposition reactions (for example, reference 10. There is evidence that the natural cleavage reaction within cells proceeds through a coupled cleavage pathway, supporting the idea that a synaptic complex of proteins and DNA is the biologically relevant process (24). Such a structure requires protein-DNA binding within the single RSS and additional binding events to bridge the two RSSs. Better understanding of these events requires an appreciation of the protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions available to the RAG proteins. This is the major subject of this report.

The natural RAG1 and RAG2 proteins of mice contain 1,040 and 527 amino acid residues, respectively. The full-length proteins are difficult to obtain in biochemically useful quantities owing to their marginal solubilities when overexpressed. Fortunately, truncated core regions of these proteins maintain all currently measurable activities and are capable of executing the complete reaction in cells with normal fidelity.

The biochemistry of the cleavage reaction has been studied by means of the expression and purification of these truncated variants, usually in the form of a fusion protein (13), and we used the same reagents in this study. The N-terminal region of the full-length RAG1 protein contains a region that has the attributes of a ring finger domain and has been expressed and subjected to structural analysis (18). This domain is capable of serving as a dimerization domain in isolation. However, it is absent in the functional truncated version of RAG1 used in this study. It follows that the homodimerization of RAG1 and the additional protein-protein interactions in the tetrameric complex must be mediated by sequences within the core regions.

To characterize the interactions that can occur among these proteins and DNA, we have purified the core regions of these two proteins, expressed as maltose binding protein fusions (called MR1 and MR2), and analyzed the physical properties of these proteins individually, mixed together, and in the absence or presence of DNA substrates. In the absence of DNA, gel filtration experiments reveal that MR1 alone exists predominantly as a homodimer, RAG2 alone has monomer, dimer, and higher forms, and coexpressed MR1 and MR2 proteins form a mixed tetramer in solution which contains two of each subunit.

DNA-protein complexes are visualized by an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). While the individual proteins can bind to DNA, they are not active in DNA cleavage. The mixture of both proteins bound to DNA forms two bands in EMSA, and we are able to purify these bands and demonstrate that only one is active in cleaving the substrate. The molecular mass of this active band is determined by Ferguson plot analysis (3, 12, 17) and found to correspond to the same tetramer of MR1 and MR2 plus one DNA molecule. Additionally, we show that cleavage of DNA in solution followed by EMSA reveals that both DNA products following cleavage can still be held together in a stable protein-DNA complex with the same mobility as the uncleaved DNA. These data suggest that a tetramer of RAG proteins is the active form bound to a single RSS in the V(D)J recombination reaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins.

Baculovirus stocks for MR1 and MR2 (13) were obtained from Martin Gellert (National Institutes of Health). MR1 and MR2 are fusion proteins, each containing an N-terminal maltose binding protein followed by the functional core region of mouse RAG1 (residues 384 to 1008) or RAG2 (residues 1 to 387) respectively. The C termini carry a polyhistidine tag followed by three tandem copies of the c-Myc epitope tag as used previously (19). MR1 and MR2 proteins were expressed individually or simultaneously by coinfection of the SF9 insect cell line. Proteins were harvested after 66 h of infection and purified on nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) charged with Ni2+ as described elsewhere (28). Fractions containing the fusion proteins were pooled and loaded onto amylose resin (New England Biolabs). The column was washed extensively with buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM EDTA) containing 0.2% Tween 20 followed by elution in buffer A plus 10 mM maltose. Protein-containing fractions were pooled and dialyzed against buffer R (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM KCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol) for 3 h. Aliquots were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Proteins purified through one chromatography step were 90% pure. Double-affinity-purified proteins were homogeneous on Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gels.

Gel exclusion chromatography.

RAG proteins were loaded onto a Superdex 200 (16 mm by 60 cm) column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and eluted with buffer R. Fractions were analyzed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–4 to 12% polyacrylamide gel, blotted to nitrocellulose, and visualized with anti-Myc monoclonal antibody 9E10. Standard proteins were loaded and developed in the same buffer system and then visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Elution data were analyzed according to the formula Kav = (Ve − V0)/(Vt − V0). The total volume (Vt) of the column is 123 ml, and the void volume (V0) of the column is 47 ml, as determined by blue dextran 2000. Fractions of 2-ml volume were collected.

DNA substrates.

Oligonucleotides were synthesized with a Perceptive Biosystems 8909 synthesizer. All substrates were 5′-end labeled with [32P]ATP, using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as indicated. 12RSS (53 bp) and 23RSS (58 bp) oligonucleotides used were M-1 (5′-GCAGGTCGACTTACACAGTGCTACAGACTGGAACAAAAACCCTCGAGGTCTCC-3′) with its complement M-2 and M-20 (5′-GGGGATCCACTTACACAGTGGTAGTACTCCACTGTCTGGCTGTACAAAAACCACGCGT-3′) with its complement M-22, respectively. Typically, one strand is labeled, annealed with its complement, purified by gel filtration on an STE Select-D G-25 spin column (5Prime-3Prime), and eluted with STE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). In early versions of the experiments, gel-purified double-stranded probes yielded the same results. Subsequent experiments were performed with a slight excess (5 to 10%) of the unlabeled strand in the annealing step to ensure that all of the labeled strand was in the double-strand form. Gel analysis of the probe confirmed the absence of single-stranded probe.

Binding and EMSA.

Binding mixtures (10 μl) contained 0.1 pmol of 32P-labeled oligonucleotide substrate DNA in a mixture containing 60 mM imidazole (pH 7.0), 50 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM CaCl2 (unless otherwise stated), 2 mM dithiothreitol, bovine serum albumin (80 μg/ml), and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). RAG1 and RAG2 were added as indicated. Unless otherwise stated, reaction mixtures were incubated on ice for 20 min. To each mixture, 3 μl of gel loading dye (30% glycerol, 0.01% bromphenol blue) was added, and samples were analyzed by electrophoresis through 5% polyacrylamide gel, using an imidazole buffer system (25 mM imidazole [pH 7.0], 0.05% Tween 20, 10% DMSO). EMSA gels were prerun for at least 30 min. Preliminary experiments to test the effect of temperature on the stability of the EMSA complexes indicated that complexes run at ambient temperature were as stable as those run at 4°C; consequently, all experiments described here were performed at room temperature. 32P-labeled DNA was detected by autoradiography using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager and ImageQuant (version 1.2) software.

Ferguson plot assay to determine the size of a protein-DNA complex was carried out with the same binding and electrophoresis conditions as used for the EMSA described above. A series of continuous gels (16 cm long) of differing total polyacrylamide concentrations (29:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide) were cast and prerun for 30 min in imidazole buffer. Binding reaction mixtures with 32P labeled DNA were loaded onto all four gels; 1 μg of each standard native protein molecular weight marker (Sigma) was mixed with the same loading buffer and run alongside the binding reactions at 300 V. Lanes containing the binding reaction mixtures were subjected to autoradiography, with the position of the bromophenol blue dye front marked. The remainder of the gels were stained with Coomassie blue. The distances migrated by the protein-DNA complexes and by each standard were then measured and divided by the distance migrated by the bromophenol blue in the same sample, giving the relative mobility (Rf). Where the protein standards contain more than one band due to the presence of charge isomers, the Rf of the major isomer was used. The data were analyzed as described elsewhere (3, 12, 17).

Cleavage activity of the protein-DNA complexes.

Binding reactions were assembled as described above, varying the divalent cation as indicated. Probe DNA was labeled on one strand. Complexes were separated by EMSA and identified by autoradiography of the wet gel. Appropriate bands were excised and incubated in cleavage buffer containing the desired cation at 37°C. DNA was recovered from the gel slice following incubation by disassembly of the complexes in SDS (0.1%, final concentration), with repeated freezes and centrifugation. The recovered DNA was analyzed by subsequent electrophoresis through a 10% polyacrylamide gel, using a Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer system. Products were detected by autoradiography of the dried gel.

RESULTS

RAG proteins in the absence of DNA.

In characterizing the protein and DNA complexes active in V(D)J recombination, we used truncated forms of the RAG proteins that have been used in previous biochemical characterizations. Protein MR1 contains the core region of RAG1 (mouse residues 384 to 1008) as part of a maltose binding protein fusion also containing a polyhistidine affinity tag and the c-Myc epitope tag. The resulting molecule has a predicted mass of 120 kDa. The RAG2 core (residues 1 to 387) was expressed the same way, with the predicted monomer mass of 92 kDa for this protein (MR2).

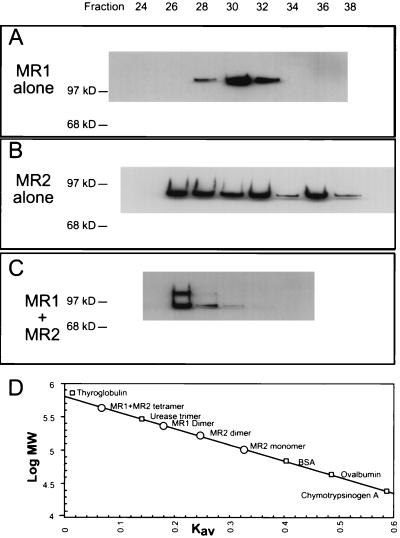

These two proteins were initially expressed individually, purified, and analyzed by size exclusion chromatography; Fig. 1A and B show Western blots of alternate fractions obtained. Recall that in an analysis of this type, larger molecules elute in earlier fractions and smaller molecules appear later. MR1 alone separated as a single major species with its elution peak centered about fraction 30. MR2 presented a more complicated pattern, with protein eluting throughout a wide span of the profile, with one distinct peak in fraction 32 and a second peak in fraction 36. Additional material representing higher-order forms is also seen. The center of the distribution of MR2 alone falls slightly above the MR2 dimer position. Figure 1C shows the contrasting behavior obtained when the two proteins were coexpressed and copurified, using the affinity tags present on both proteins. The infection was deliberately biased to produce more MR2 than MR1. The resulting profile shows that the majority of both proteins eluted together in fraction 26. Additional MR2 continued to elute in later fractions. This result suggests that both proteins are present together in a larger complex than is predominant with either protein in isolation. The molecular weight of the various peaks is determined from a curve generated from protein standards and is shown in Fig. 1D. The MR1 peak in Fig. 1A corresponds to an apparent molecular mass of 247 kDa. The two peaks seen with MR2 in isolation correspond to 183 and 102 kDa, respectively. The peak obtained with coexpressed proteins represents an apparent mass of 443 kDa. The theory of size exclusion chromatography predicts a linear relationship for the standard curve, as used here. The actual situation may deviate from the theoretical since the standard proteins may not be perfect globular structures completely free of chemical interaction with the gel matrix. We have therefore also recalculated the standard curve as a cubic polynomial fit (not shown). This increases the fit of the standards to the curve from a least-squares value of 0.995 for the linear fit to a value of 0.999 for the polynomial fit. With this alternate standard curve, the peak from Fig. 1C would represent a slightly greater predicted mass of 459 kDa. The difference in calculation does not alter our interpretation. These data indicate that MR1 in isolation exists predominantly as a dimer and MR2 alone exists as a mixture of monomer, dimer, and larger forms. The coexpressed proteins in contrast form a distinct larger complex close to the expected mass of 426 kDa anticipated for two of each. The slightly larger than predicted mass, if significant, may represent an elongated shape for the tetrameric structure.

FIG. 1.

Gel filtration analysis of RAG proteins. (A to C) Western blots of alternate fractions collected by chromatography over Superdex 200 resin. (A) Purified MR1 (120-kDa monomer) shows a single peak. (B) Purified MR2 (92-kDa monomer) shows peaks in fractions 32 and 36 and additional higher forms. (C) Coexpressed and purified complex of MR1 plus MR2 shows a single peak which contains both proteins. (D) Calibration curve for protein standards (squares) and location of chromatogram peaks (circles). BSA, bovine serum albumin.

RAG proteins in the presence of DNA.

We and others have previously shown that DNA-protein complexes can be assembled with various combinations of RAG proteins and labeled oligonucleotide substrates (1, 2, 7, 15, 25). These complexes can be visualized by EMSA. Figure 2 shows the typical result of such an analysis. Here we show the behavior of complexes formed on a 12RSS or 23RSS probe, with MR1 alone or with coexpressed MR1 and MR2. In addition, this analysis was performed in the absence or presence of competitor dI-dC. Lane 1 shows the MR1 alone assembling on a 12RSS probe in the absence of dI-dC. Multiple bands can be seen extending up to the sample well. Plotting of the mobilities of these bands from this or similar gels indicates that they fall on an exponential curve, consistent with a simple multimeric relationship between them (data not shown). A similar behavior occurs with a 23RSS DNA (lanes 2 and 3). In fact (data not shown), the same behavior can be obtained with unrelated DNA as a probe, suggesting that the bulk of the DNA binding in this case is not sequence specific. The ability of RAG1 to bind DNA nonspecifically has been reported before (1, 15, 25). This point is reinforced by the behavior of the same proteins and probes in the presence of dI-dC competitor (lanes 7 to 9), where the higher-order bands disappear. In contrast, when both proteins are present (lanes 4 to 6 and 10 to 12), a new band which is resistant to competition appears. We and others have shown that the lower band contains only RAG1 protein plus DNA, while the upper band contains both RAG1 and RAG2 (1, 15, 25). This experiment was performed with the protein mixture analyzed in Fig. 1C, in which MR1 is fully associated in the tetrameric form prior to the addition of the DNA. Despite effort to overrepresent the MR2 in the mixture, the lower band persists, suggesting that the MR2 protein can be displaced from the preexisting MR1-MR2 tetramer. It is not clear from our data if the bottom band represents MR1 originally present in a tetramer of MR1 and MR2 that spontaneously dissociated prior to DNA binding. Alternatively, the binding to DNA or subsequent steps may destabilize the interaction of MR1 to MR2, allowing some loss of MR2 from the tetramer. We hope to address this issue in future experiments. We have previously found that the binding of MR2 alone to DNA is very weak and is easily competed with dI-dC (15). Others, using different conditions, detected no binding (4, 23, 25). Consequently, we feel that the important interactions involving RAG2 occur in the presence of RAG1, and we have not pursued the description of the MR2 alone on DNA.

FIG. 2.

EMSA analysis of protein binding to DNA. The two probes 12RSS (lanes 1, 4, 9, and 12) and 23RSS (lanes 2, 3, 5 to 8, 10, and 11) show equivalent behavior. MR1 alone or coexpressed MR1 and MR2 are bound in the absence (lanes 1 to 6) or presence (lanes 7 to 12) of competitor dI-dC. Protein binding to the 23RSS was performed at two concentrations. MR1 alone in the absence of dI-dC forms multiple bands. One band (marked) is unique to lanes that contain MR1 plus MR2.

Since the composition and stoichiometry of the protein complex on DNA are more relevant to the V(D)J recombination mechanism than the behavior of the purified proteins themselves, we used Ferguson plot analysis to determine the molecular weight of the complexes visualized by EMSA.

In EMSA analysis, the mobility of the complex under native conditions is a complicated product of size, shape, charge and other forces such as interaction with the gel matrix. As a result, one cannot assume that the relative mobilities of different bands in a single gel are direct reflections of the masses of their components. The principle behind Ferguson plot analysis is that by using a series of gels in all ways identical except for the concentration of acrylamide, one can isolate the sieving properties of the gels from all other forces, which remain constant. The change in mobility of the complex as a function of change in acrylamide concentration turns out to be directly proportional to the molecular radius of the particles being analyzed. This in turn is related exponentially to the molecular mass, given the simplifying assumption of a globular structure. For the purposes of determining the stoichiometry of a complex, this assumption is not dangerous since the difference in mobility of a monomer versus a dimer is much more dramatic than the nonlinearity introduced by a consideration of shape. This technique was originally applied to pure protein electrophoresis, but several studies have successfully used it to characterize the masses of protein-DNA complexes (3, 12, 17).

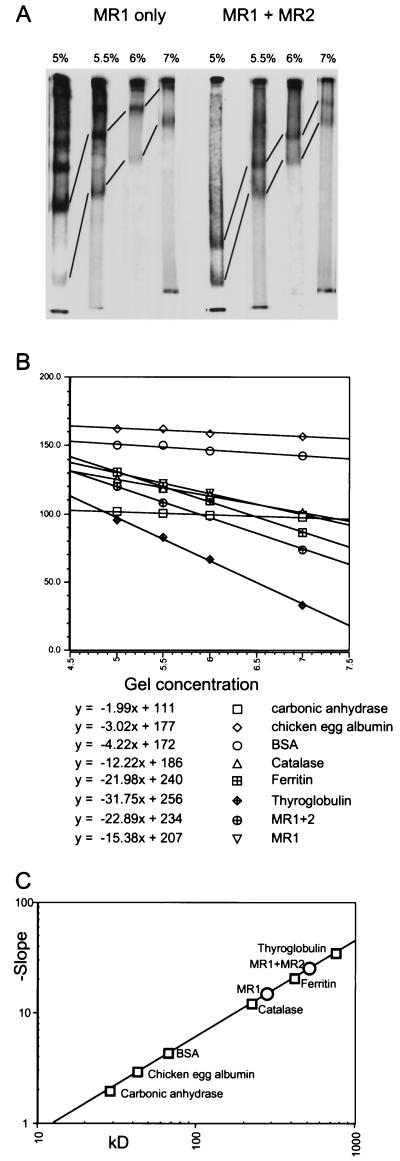

Figure 3A shows the change in mobilities obtained in a series of gels for complexes that form on the 12RSS probe with MR1 alone or in the presence of MR2. As the acrylamide concentration increases, the equivalent bands migrate more slowly, as shown by the connecting lines. Similar gels are run for each of the standards (data not shown). For each family of bands, a plot of the log of the relative mobility versus acrylamide concentration falls on a line (Fig. 3B), the slope of which is proportional to molecular radius. Small proteins sieve easily in all the gels and do not exhibit a large change in mobility, while large proteins are more sensitive to pore size and show a steeper slope. This allows one to construct a standard curve by using markers of known mass (Fig. 3C). The slopes obtained for the complexes of MR1 or MR1 plus MR2 with DNA can then be transformed into an apparent molecular mass by using the standard curve. In this analysis, the lowest bands formed by MR1 alone and the lower band formed in the presence of MR2 gave the same mass, 295 kDa. This is in good accord with the expected mass of 275 kDa for a complex composed of two MR1 molecules (120 kDa each) plus one probe DNA molecule (35 kDa). This result confirms the interpretation of previous authors (1, 15, 25) that the EMSA bands obtained with MR1 alone and the comigrating band obtained in the presence of both proteins contain only MR1. We add to this observation the appreciation that it is actually a dimer of MR1 present within this complex. Similarly, the upper band obtained with both RAG proteins has already been shown to contain both proteins (25). We have previously shown that this band excised from the gel apparently contains an equal molar ratio of the two (15). Here we have shown that the mass of the complex is most consistent with a tetramer of protein on DNA. Given our previous result that the stoichiometry is equal, we conclude that there are two molecules of each protein per complex. Purely on the basis of this mass estimate, we cannot rule out the possibility of two DNA molecules being present in this complex, but the interpretation of one DNA molecule is most consistent with other experiments (see Discussion). The complex known to contain both MR1 and MR2 (second from the bottom in Fig. 3A) by this analysis yielded an apparent mass of 464 kDa. This is strikingly close to the predicted mass of 459 kDa for a tetramer of two MR1 molecules plus two MR2 molecules and one probe DNA molecule. The higher-order bands visible in the MR1-only gels are more difficult to size with certainty, as their slower migration leads to a larger consequence of measurement errors. Our calculations are consistent with the interpretation that these represent progressive multimers of MR1 dimers on a single DNA molecule. Overall, these experiments demonstrate that MR1 binds to DNA as a dimer, and when MR2 is present, the stable complex with DNA contains two of each protein.

FIG. 3.

Ferguson plot analysis of RAG protein-DNA complexes. (A) Isolated lanes from EMSA gels show the change in mobility of the native protein-DNA complexes in gels that differ solely in acrylamide concentration (indicated). Bands that represent the same complex under different gel conditions are linked by lines. Binding reactions were assembled in the absence of dI-dC competitor. The mathematical treatment of migration normalizes each lane to the migration of the dye front, thereby correcting for slight differences in runs between gels. (B) Calculation of the characteristic slopes. Migration data as in panel A for the standard proteins and selected experimental bands are plotted as a function of gel concentration. The y axis shows mobility calculated according to the formula y = 100 [log (Rf ∗ 100)]. The relationship between migration and gel concentration is exponential, so the semilog plot yields a line. Rf represents the absolute migration divided by the migration of the dye front for that gel. Each line is described by the formula y = mx + b, where m is the slope. BSA, bovine serum albumin. (C) Ferguson plot. The inverse of the slope is directly proportional to the molecular radius of the particle, which in turn is directly proportional to mass for globular particles. Standards (squares) are plotted, and experimental samples (circles) are interpreted from the resulting standard curve.

Cleavage activity of the tetramer complex.

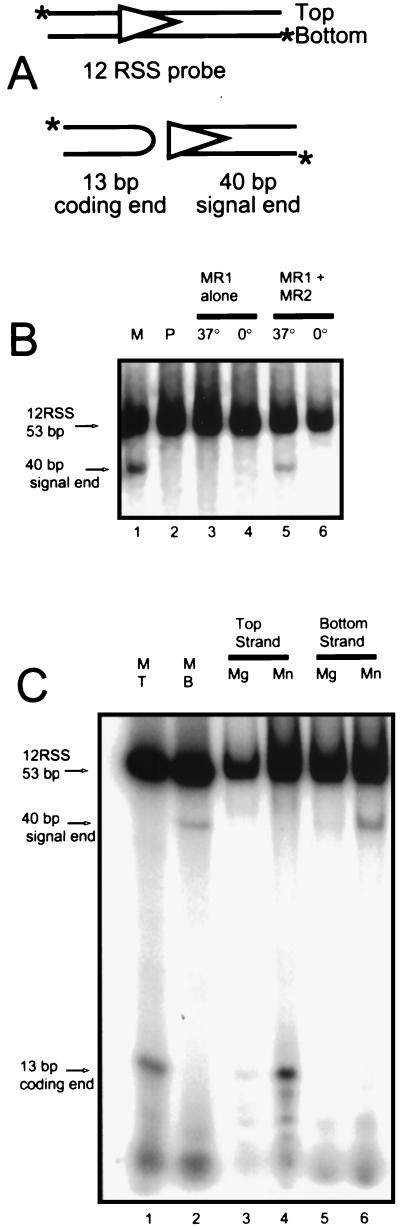

Our results indicate that RAG1 and RAG2 can form a tetrameric complex in the absence or the presence of DNA. We wished to determine whether that form was the only form capable of carrying out the cleavage reaction. One complication to experiments performed in solution is that reassortment of the components can occur. Even with complexes assembled under conditions of MR2 excess, we find that a band representing a species containing MR1 alone appears in the EMSA gels. This finding suggests that MR2 binds with sufficient weakness to disassociate from the protein-DNA complex. We therefore attempted the cleavage reaction within a gel slice in which the individual complexes had already been separated from each other. Figure 4A shows a representation of the probes used in the following assays. The duplex oligonucleotide contains a 12RSS and can be 5′-end labeled on either the top or bottom strand as drawn. In an initial experiment, probe labeled on the bottom strand was used (Fig. 4B). The expected labeled product of the cleavage reaction would be the 40-bp signal end. Lane 1 is a marker lane in which the cleavage reaction was performed in solution; lane 2 contains the probe alone. The remaining lanes represent complete reactions that were assembled on ice and then separated through a native gel to yield the two bands previously seen (as in Fig. 2, lane 12). These bands were identified, excised from the gel, divided in two, and reincubated at the indicated temperature in the presence of reaction buffer. After 20 min, SDS was added to the gel slices, and the DNA was eluted and analyzed on another gel (Fig. 4B). As can be seen (lane 5), cleavage activity was detected only in the band corresponding to the upper EMSA band incubated at 37°C. The identical sample maintained at 0°C retained the original status (lane 6). This indicates that the cleavage truly occurred following the gel separation and not during the initial assembly of the reaction. Furthermore, the faster EMSA band already shown to contain only MR1 was not active in the cleavage assay (see below).

FIG. 4.

Cleavage assay applied to gel-purified bands. (A) Schematic representation of the two probes used for the assay. The 12RSS probe is represented by the triangle, with cleavage occurring at the heptamer border (vertical side) to produce the hairpinned coding end (13 bp) and signal end (40 bp). Only one of these products will be labeled, depending on which DNA strand is 5′-end labeled initially (asterisk). (B) Complexes assembled on ice in Mn2+ with both MR1 and MR2 were separated on a native gel, and the two bands were excised and incubated at the indicated temperature. The DNA was recovered and run in a second gel in TBE buffer. Lane M, marker of the cleavage reaction performed in solution; lane P, the unreacted probe. The excised band known to contain only the MR1 protein does not exhibit cleavage activity (lanes 3 and 4), but the excised band which contains both MR1 and MR2 (lanes 5 and 6) cleaves its DNA when incubated at 37°C. (C) Cleavage of probe in the excised MR1-MR2 band occurs only in Mn2+. Parallel reactions were assembled in Mg2+ and Mn2+ with 12RSS probes labeled individually on the top (T) or bottom (B) strand. A native gel was run, and the complexes containing MR1 plus MR2 were excised and then incubated in their original reaction buffer. The DNA was recovered and run in a gel in TBE buffer. Lanes 1 and 2 are cleavage reactions in solution for probes labeled on the top or bottom strand as markers. Activity on the probe labeled on the top (lanes 3 and 4) and bottom (lanes 5 and 6) strands is much stronger in the presence of Mn2+ than Mg2+.

In a more refined experiment (Fig. 4C), we concentrated entirely on the behavior of the complex containing tetrameric MR1 plus MR2. Two probes were used, representing the 12RSS DNA labeled uniquely on the top or bottom strand. When the top strand is labeled, cleavage generates a 13-bp coding end, while the labeled bottom strand is cleaved to form a 40-bp signal end. Again, the protein-DNA complexes were assembled in solution on ice and separated under native conditions, and the band of interest was excised. In this experiment, parallel reactions were assembled in the presence of Mg2+ or Mn2+. Reactions were performed with the top strand (lanes 1, 3, and 4) or bottom strand (lanes 2, 5, and 6) labeled as probes; lanes 1 and 2 are marker lanes in which cleavage was allowed to occur in solution. The MR1-MR2 complexes were isolated under EMSA conditions, excised, and then incubated in reaction buffer containing the original metal ion. Signal ends and coding ends were generated as previously found in solution. We find that cleavage occurs primarily in the Mn2+ lanes, yielding both expected products.

We subsequently found (data not shown) that similar results could be obtained by assembling the initial reaction in the presence of Ca2+ with later incubation in Mn2+ following gel separation, as previously shown for conventional binding and cleavage experiments (1, 8). Additional experiments were performed with 23RSS probes equivalent to those shown. Weaker cleavage was obtained with the same pattern as presented with the 12RSS (data not shown). This is consistent with the known preference of the cleavage reaction for the 12RSS in the absence of HMG1. Furthermore, experiments were also conducted in the presence of both 12RSS and 23RSS simultaneously in the hopes that an additional synaptic complex could be identified (8) or to assess whether the presence of both DNA species would permit cleavage in the presence of Mg2+. Neither result was obtained (data not shown), which we view as additional evidence that this tetrameric protein complex is assembled on a single molecule of probe DNA.

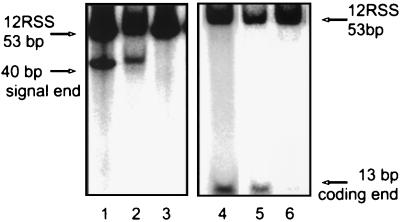

The tetrameric complex retains both products following cleavage.

A variation of this experiment produced an interesting result presented as Fig. 5. The same probes were used as in the previous experiment, labeled individually on either the bottom (lanes 1 to 3) or top (lanes 4 to 6) strand. The cleavage reaction was assembled in solution with both MR1 and MR2 proteins in the presence of Mn2+. This time the reaction was allowed to cleave the probe for 20 min at 37°C. The reaction was separated by electrophoresis on a native gel, again producing the two bands previously characterized. Both bands were excised separately. The DNA within these bands was extracted and analyzed in a second gel. Lanes 1 and 4 are marker lanes cleaved in solution. DNA from the upper band, representing the tetrameric MR1-MR2 complex, is shown in lanes 2 and 5; the DNA derived from the faster EMSA band which contains MR1 alone is in lanes 3 and 6. Quantitation of the DNA in each lane indicates that approximately 30% of the cleaved signal is present in lanes 2 and 50% is in lane 5 compared to the control lanes. Since part of the DNA is lost during the elution from the gel slice, we estimate that at least 50% of the cleavage products are retained in these complexes. We see that both cleaved signal-end and coding-end products were obtained from the tetrameric protein complex, while no cleavage products were found in the MR1-only complex. It is apparent that following cleavage in solution, the tetrameric complex was able to retain both signal and coding products. Furthermore, following cleavage the tetrameric complex is stable with respect to RAG2 binding since none of the cleaved complex was converted into the MR1-only form. Further analysis of the stability and interconversions of these complexes is the subject of ongoing investigation in our laboratory. One important implication of this observation is that DNA-protein contacts must occur within the coding DNA outside the RSS. Retention of coding-end DNA following cleavage has been previously observed in the study of synaptic complexes (7). These contacts would permit the RAG proteins to play additional roles in the subsequent processing and joining stages of the recombination reaction.

FIG. 5.

Retention of both signal ends and coding ends in the MR1-MR2 complex. The same two probes used for Fig. 4 were assembled into cleavage reactions and incubated at 37°C. Complexes were separated in a native gel, and bands corresponding to MR1-MR2 complex (lanes 2 and 5) or the MR1-alone complex (lanes 3 and 6) were excised. DNA was recovered and run in a TBE gel. Lanes 1 and 4 are cleavage reactions in solution for probes labeled on the bottom or top strand as markers.

DISCUSSION

The V(D)J recombination reaction is believed to pass through a synaptic intermediate in which one 12RSS and one 23RSS are aligned prior to cleavage (7). The proteins RAG1 and RAG2, aided by the ubiquitous DNA bending protein HMG1, are sufficient to specify this pairing. A significant puzzle remains to determine the structural basis by which these proteins interact differently with the two types of RSS and prefer to cleave complexes that contain one of each type over pairs of the same type of RSS. It has been argued that the 12/23 rule is enforced at the synaptic step (7) or subsequently at the stage of double-hairpin formation (31). We are addressing the challenge of understanding the full cleavage reaction by first attempting to identify and characterize the constituent protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions that contribute to the larger complex. Both RAG1 and RAG2 proteins are known to be necessary for the site recognition (4, 23) and various cleavage steps (2, 9, 29). They can also both be found in a complex that can be identified by EMSA (1, 7, 15, 25), and we report here that the EMSA complex is capable of cleaving the DNA; there has been no exploration of the stoichiometry or organization of protein and DNA in the complex. This functional unit appears to be a tetramer composed of two molecules of each RAG protein. In isolation the purified core region of RAG1, expressed as a fusion protein (MR1) with maltose binding protein, exists predominantly as a dimer. The fusion partner itself does not dimerize (New England Biolabs product literature). The RAG2 derivative (MR2) containing a functional core of that protein as a fusion construct also appears to form higher-order protein complexes in isolation. Monomer, dimer, and unresolved higher forms of MR2 are all present in the gel exclusion chromatogram. More striking is the analysis of the two proteins when coexpressed. We find that a tetramer-sized complex containing both proteins is the dominant form in the absence of DNA. A complex containing RAG1 and RAG2 has been identified previously in immunoprecipitates of cell extracts (14). In this previous study, the two proteins may have been tethered by DNA derived from the cell rather than truly representing a direct protein interaction. This concern is eliminated by using the highly purified proteins in this study.

These results are extended by studies of the complexes that assemble on RSS-containing substrates. Previous reports indicate that a mixture of RAG1 and RAG2 leads to two distinct complexes as revealed by EMSA (1, 15, 25). Using Ferguson plot analysis (3, 12, 17), we were able to determine that the faster-migrating complex behaves as a particle with molecular radius appropriate for a dimer of MR1 on one molecule of the probe. The slower-migrating complex, in contrast, is known to contain both RAG1 and RAG2 (15, 25) and in our analysis appears to be composed of the same tetramer as observed above plus one DNA molecule. This is consistent with our previous observation of apparent equimolar ratios of the two proteins when this EMSA band was excised from the gel and analyzed by Western blotting (15). We are further able to show that only the EMSA band that contains both RAG1 and RAG2 derivatives is capable of cleaving its DNA. The faster-migrating EMSA band containing a dimer of RAG1 derived from the same binding reaction does not cleave the DNA. This is additional evidence that RAG2 plays a direct role in the cleavage reaction rather than indirectly activating a nuclease in RAG1. If RAG2 were able to operate transiently to activate RAG1 in a hit-and-run manner, then the faster-migrating complex would be competent for cleavage since it has been exposed to RAG2.

There is a logical difficulty posed by the cleavage of the coding DNA outside the RSS. Since the cleavage event occurs at the border of the RSS, there is no basis for sequence-specific binding to the adjacent coding DNA. Yet in the absence of binding, there would be nothing to prevent the newly cleaved hairpin-ended coding DNA from separating from its future partner. We favor the argument that the RAG proteins exhibit both sequence-specific and nonspecific binding behaviors. While sequence-specific binding is required to position the proteins at the heptamer and nonamer, nonspecific binding is required to position additional protein at the coding DNA flanking the RSS. The tetrameric protein complex would permit this by coordinating binding to the RSS and the coding flank. Persistent binding to the coding flank would retain that hairpinned product for further processing.

We have observed that both cleaved products are retained in the EMSA complex containing RAG1 and RAG2. Others have not detected the same phenomenon in EMSAs using different experimental conditions (1, 8). Our studies use conditions that differ from those used in the cited studies and have been optimized so that chemical cross-linking is not necessary to maintain the integrity of the complex. A significant experimental difference is the inclusion of 10% DMSO in the native gels and electrophoresis buffer. The presence of DMSO in the binding reaction is now standard (1, 8, 15, 25), and we feel that it helps stabilize the proteins and prevent aggregation. We added a nonionic detergent for the same reason. We also note that using imidazole as a pH buffer and lowering the pH to 7.0 reduces the likelihood of the polyhistidine tags interacting with each other through a bridging metal ion. Retention of the coding end was observed in the analysis of synaptic complexes in a biotin pull-down assay (7). Our observation represents an extension of that finding, using a different system in which there is no possibility that a larger aggregate could entrap the coding DNA product.

In trying to appreciate the role of the protein tetramer identified in this report in the normal biochemistry of the recombination reaction, it is important to be certain of the DNA content within this complex. At least two possibilities are consistent with our data. The tetrameric complex identified here might represent exactly half of the synaptic complex. Additional protein-protein interactions would hold together two tetramers, each carrying one RSS. The 12/23 rule would act either at the level of stabilizing the assembly of that larger complex or at a subsequent chemical step. Alternatively, the protein tetramer may possess sufficient binding capacity to incorporate two RSS-containing DNA molecules. We believe that the complexes examined in this study contain only one DNA molecule. The evidence is indirect, and we are pursuing the question. In support of our interpretation are the following data. First, the analysis in Fig. 3 yields a mass for the complex close to the theoretical mass of a tetramer plus one DNA molecule. Second, the conditions that we used in this assay do not include HMG1 protein. This is significant because previous work (7) indicates that a significant paired complex containing two DNA molecules was obtained only in the presence of that protein. Third, our result of cleavage performed on gel-purified complexes shows preferred cleavage in the presence of Mn2+ over Mg2+ ions. We have attempted to perform the same experiment with mixtures of 12RSS and 23RSS DNAs (data not presented). Creation of paired complexes should exhibit equivalent cleavage with both ions; however, this was not observed, indicating that the complexes that we examined did not contain both DNAs.

We know that there are contacts between RAG1 at both the heptamer and nonamer (15) (though not necessarily the same monomer of RAG1) and indirect evidence that RAG1 interacts with the coding flank (20). This leads us to favor the proposal that two protein tetramers would be required to form the synaptic structure, since binding to the heptamer, the nonamer, and the coding flank probably occupies more than half of the binding sites available in one tetramer, leaving too few additional binding sites for a symmetric interaction with a second RSS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NIH grant AI41711 to M.J.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akamatsu Y, Oettinger M A. Distinct roles of RAG1 and RAG2 in binding the V(D)J recombination signal sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4670–4678. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besmer E, Mansilla-Soto J, Cassard S, Sawchuk D J, Brown G, Sadofsky M, Lewis S M, Nussenzweig M C, Cortes P. Hairpin coding end opening is mediated by RAG1 and RAG2 proteins. Mol Cell. 1998;2:817–828. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bullock B P, Habener J F. Phosphorylation of the cAMP response element binding protein CREB by cAMP-dependent protein kinase A and glycogen synthase kinase-3 alters DNA-binding affinity, conformation, and increases net charge. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3795–3809. doi: 10.1021/bi970982t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Difilippantonio M J, McMahan C J, Eastman Q M, Spanopoulou E, Schatz D G. RAG1 mediates signal sequence recognition and recruitment of RAG2 in V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1996;87:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eastman Q M, Leu T M J, Schatz D G. Initiation of V(D)J recombination in-vitro obeying the 12/23-rule. Nature. 1996;380:85–88. doi: 10.1038/380085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gellert M. Recent advances in understanding V(D)J recombination. Adv Immunol. 1997;64:39–64. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60886-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiom K, Gellert M. Assembly of a 12/23 paired signal complex: a critical control point in V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell. 1998;1:1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiom K, Gellert M. A stable RAG1-RAG2-DNA complex that is active in V(D)J cleavage. Cell. 1997;88:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81859-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim D R, Oettinger M A. Functional analysis of coordinated cleavage in V(D)J recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4679–4688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavoie B D, Chaconas G. Transposition of phage Mu DNA. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;204:83–102. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79795-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis S M. The mechanism of V(D)J joining: lessons from molecular, immunological, and comparative analyses. Adv Immunol. 1994;56:27–150. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May G, Sutton C, Gould H. Purification and characterization of Ku-2, an octamer-binding protein related to the autoantigen Ku. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3052–3059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McBlane J F, van Gent D C, Ramsden D A, Romeo C, Cuomo C A, Gellert M, Oettinger M A. Cleavage at a V(D)J recombination signal requires only RAG1 and RAG2 proteins and occurs in two steps. Cell. 1995;83:387–395. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahan C J, Sadofsky M J, Schatz D G. Definition of a large region of RAG1 that is important for coimmunoprecipitation of RAG2. J Immunol. 1997;158:2202–2210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mo X, Tu B, Sadofsky M. RAG1 and RAG2 cooperate in specific binding to the recombination signal sequence in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7025–7032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oettinger M A, Schatz D G, Gorka C, Baltimore D. RAG-1 and RAG-2, adjacent genes that synergistically activate V(D)J recombination. Science. 1990;248:1517–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.2360047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orchard K, May G E. An EMSA-based method for determining the molecular weight of a protein-DNA complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3335–3336. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.14.3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodgers K K, Bu Z, Fleming K G, Schatz D G, Engelman D M, Coleman J E. A zinc-binding domain involved in the dimerization of RAG1. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:70–84. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadofsky M J, Hesse J E, McBlane J F, Gellert M. Expression and V(D)J recombination activity of mutated RAG-1 proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5644–5650. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.24.5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadofsky M J, Hesse J E, van Gent D C, Gellert M. RAG-1 mutations that affect the target specificity of V(D)J recombination: a possible direct role of RAG-1 in site recognition. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2193–2199. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawchuk D J, Weis-Garcia F, Malik S, Besmer E, Bustin M, Nussenzweig M C, Cortes P. V(D)J recombination: modulation of RAG1 and RAG2 cleavage activity on 12/23 substrates by whole cell extract and DNA-bending proteins. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2025–2032. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schatz D G, Oettinger M A, Baltimore D. The V(D)J recombination activating gene, RAG-1. Cell. 1989;59:1035–1048. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90760-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spanopoulou E, Zaitseva F, Wang F, Santagata S, Baltimore D, Panayotou G. The homeodomain region of Rag-1 reveals the parallel mechanisms of bacterial and V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1996;87:263–276. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steen S B, Gomelsky L, Speidel S L, Roth D B. Initiation of V(D)J recombination in vivo: role of recombination signal sequences in formation of single and paired double-strand breaks. EMBO J. 1997;16:2656–2664. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swanson P C, Desiderio S. V(D)J recombination signal recognition: distinct, overlapping DNA-protein contacts in complexes containing RAG1 with and without RAG2. Immunity. 1998;9:115–125. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 1983;302:575–581. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Gent D C, Hiom K, Paull T T, Gellert M. Stimulation of V(D)J cleavage by high mobility group proteins. EMBO J. 1997;16:2665–2670. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Gent D C, McBlane J F, Ramsden D A, Sadofsky M J, Hesse J E, Gellert M. Initiation of V(D)J recombination in a cell-free system. Cell. 1995;81:925–934. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Gent D C, Mizuuchi K, Gellert M. Similarities between initiation of V(D)J recombination and retroviral integration. Science. 1996;271:1592–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Gent D C, Ramsden D A, Gellert M. The Rag1 and Rag2 proteins establish the 12/23-rule in V(D)J recombination. Cell. 1996;85:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West R B, Lieber M R. The RAG-HMG1 complex enforces the 12/23 rule of V(D)J recombination specifically at the double-hairpin formation step. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6408–6415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]