Abstract

Developmental brain injury describes a spectrum of neurological pathologies resulting from either antenatal or perinatal injury. This includes both cognitive and motor defects that affect patients for their entire lives. Developmental brain injury can be caused by a spectrum of conditions including stroke, perinatal hypoxia-ischemia and intracranial haemorrhage. Additional risk factors have been identified including very low birthweight, mechanical ventilation and oxygen (O2) supplementation. In fact, infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia, an inflammatory disease associated with disrupted lung development, have been shown to have decreased cerebral white matter and decreased intracranial volumes. Thus, there appears to be a developmental link between the lung, O2 and the brain that leads to proper myelination. Here, we will discuss what is currently known about the link between O2 and myelination and how scientists are exploring mechanisms through which supplemental O2 and/or lung injury can affect brain development. Consideration of a link between the diseased lung and developing brain will allow clinicians to fine tune their approaches in managing preterm lung disease in order to optimize brain health.

Keywords: White matter Injury, neurodevelopmental impairment, oxygen, prematurity, animal models

Graphical Abstract

Here we review the literature to shed light on the possibility that high oxygen levels and/or lung injury, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, can lead to neurodevelopmental impairment. The literature is especially convincing that these factors affect the neurodevelopment of extremely preterm or very low birthweight infants.

1. Introduction

Neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) in preterm and low birthweight infants has been studied since the early 1970s. It has long been recognized that infants with worse lung disease were more likely to have worse neurodevelopmental outcomes. But the reason for this has been assumed to be multifactorial, relating to especially steroid exposure and intercurrent infections such as sepsis, pneumonia and necrotizing enterocolitis. NDI is defined by the presence of Bayley Scales of Infant Development scores <2SD below the mean, blindness, deafness not corrected by hearing aids, and/or cerebral palsy (CP) (Hintz et al., 2007). CP is a non-progressive disorder of motor control that causes lifelong muscle spasticity. Impairment is often significant enough to affect activities of daily living such as self-care and ambulation (Graham et al., 2016). CP also causes significant pain as patients get older (Fehlings, 2017). These clinical signs are manifestations of injury to oligodendrocytes (OLs) or white matter injury (WMI). In the US, 12,000 babies are affected annually (Bairoliya & Fink, 2018; Kurinczuk, White-Koning, & Badawi, 2010; Murray et al., 2013; Van Naarden Braun et al., 2016). CP occurs in approximately 6% of infants born at very low birthweight (VLBW) (Wilson-Costello, 2007) and nearly 15% of infants born at the limits of viability (Hintz et al., 2011). Among infants with cystic periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) in 1997 in the EPIPAGD study group, 61% developed CP (Beaino et al., 2010). However, between 1993 and 2012, rates of cystic PVL decreased from 8% to 4% in infants born between 26- and 28-weeks’ gestation (Stoll et al., 2015). Evidence supports a significantly higher risk for CP in multiples as opposed to singletons (Topp et al., 2004). While CP rates had been stable in studies before 2010, there is recent evidence that rates are decreasing for multiples in some geographical areas (Perra et al., 2020). This is likely due to improved care for preterm and VLBW infants in these areas. At the same time, because accumulating evidence suggests improving survival without NDI at the limits of viability, providers are now resuscitating newborns as young as 22 weeks’ gestational age (Hintz et al., 2011; Younge et al., 2017). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that rates of preterm lung disease and NDI will increase. Unfortunately, at this time, preventatives for CP for preterm patients are limited only to intrapartum magnesium, the effectiveness of which is controversial (Rouse et al., 2008). While it is known that prematurity and low birthweight increase risk for CP, other diagnoses can contribute to the pathogenesis of CP. These include traumatic brain injury, infections such as meningitis, sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis, arterial ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhages and disruptions to cerebral blood flow. Two cellular mechanisms, inflammation and oxygen (O2) exposure are common in the evolution and management of these conditions (Fig 1). Here we will discuss bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), another clinical condition in which inflammation and O2 oxygen exposure are implicated and explore its pathogenetic relationship with NDI.

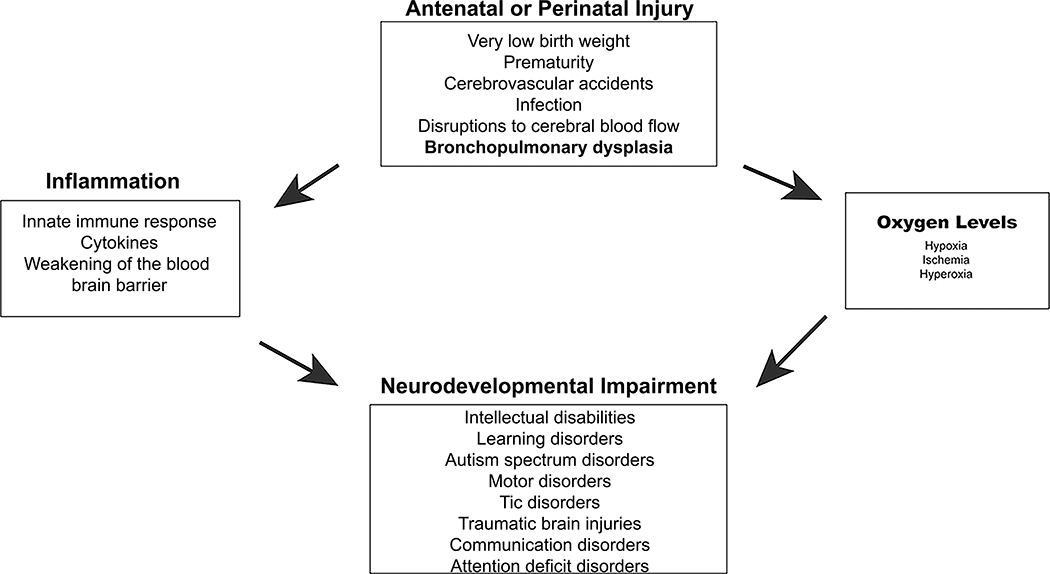

Figure 1: Mechanisms of NDI caused by antenatal or perinatal injury.

Schematic showing the relationship between various antenatal and perinatal conditions (top square) and NDI (bottom square). The square on the left indicates levels of oxygen that can cause CNS injury leading to NDI. The box on the left indicates how the immune system can contribute to CNS injury leading to NDI.

2. Preterm lung disease may be associated with neurodevelopmental impairment.

BPD is a disease resulting from disrupted development of the lungs due to preterm birth and therefore exposure to insults such as O2 and mechanical ventilation (Northway, Rosan, & Porter, 1967). It affects 10,000–15,000 babies in the United States annually (Davidson & Berkelhamer, 2017). At present, approximately 43% of babies born at very low birth weight (VLBW), mostly ≤28 weeks’ gestational age, are affected by BPD. The number of studies correlating NDI with BPD is small but growing. Initially Byrne et al., (1989) concluded in a study of 41 preterm infants (<1500g) that neuromotor development of patients with BPD was the same as patients without (Byrne, Piper, & Darrah, 1989). In the same year, Perlman and Volpe published the finding of a movement disorder in 10 infants with severe BPD (Perlman & Volpe, 1989). This involved extrapyramidal movements similar to chorea and akathisia. Of the 7 patients that survived, 4 retained abnormal movements at 21 months old (Perlman & Volpe, 1989). In 2000, Katz-Salamon and colleagues studied 86 preterm infants without intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) or PVL. Of this group, 43 had chronic lung disease and 43 did not. Using the Griffiths’ developmental test at 10 months old, they found that while overall motor assessment did not differ between the two groups, other parameters of NDI were significant in the group with chronic lung disease (Katz-Salamon, Gerner, Jonsson, & Lagercrantz, 2000). In 2008 Jeng et al., published their results from 103 infants ≤1500g examined using the neonatal neurobehavioral examination (Chinese version), at 36 and 39 weeks’ post menstrual age (PMA). They found that in this group the rates of NDI increased with severity of diagnosed BPD (Jeng et al., 2008). Malavolti and colleagues (2018) studied 610 children born at <30 weeks PMA and assessed at 2 years follow up. They found that even after adjusting for several variables including IVH, severe BPD remained an independent predictor of NDI (Malavolti et al., 2018). Mild or moderate BPD was not found to be an independent predictor of NDI. Another study by Lee et al., (2019) examined 56 preterm infants with no evidence of focal abnormalities on neuroimaging (J. M. Lee et al., 2019). Of these infants, 33 were independently diagnosed with BPD and 23 were without BPD. Of this population, patients with BPD had smaller cerebral white matter volumes and reduced fractional anisotropy of several white matter tracts as compared to the patients without BPD (J. M. Lee et al., 2019). Parikh and co-authors examined 392 preterm infants (≤32 PMA) by MRI and found severe BPD was significantly correlated with diffuse white matter abnormality (Parikh et al., 2020). In a group of 89 preterm infants diagnosed with varying degrees of BPD, Gallini et al., (2021) found not only a higher risk of NDI in infants with severe BPD but also in the patients with mild BPD at 24 months corrected age (Parikh et al., 2020). These studies together support the hypothesis that severe BPD may independently contribute mechanisms leading to NDI and that even mild BPD or other types of chronic lung disease may also contribute to NDI.

3. Oxygen levels influence both lung and nervous system development

Remarkably, unlike other organ systems, both the brain and the lung continue to develop postnatally. Effectively, this means that both the brain and lung are incompletely formed at the time of, certainly preterm, but even full-term birth, and any injuries that occur at this time can profoundly impact the continuing normal development of these organs. For the lung, the transition from the aquatic environment of the amniotic sac to the dry extrauterine environment requires dramatic adjustments. First, there is the increase in pulmonary blood flow accompanied by the closure of the ductus arteriosus, decreased pulmonary vascular resistance and increased systemic resistance. This, too, is triggered in part by increases in first PAO2 then PaO2 (Rudolph, 1991). Simultaneously, antioxidant defences must increase. After this, postnatal human lung development involves two primary events: 1) maturation or remodeling of primitive alveoli that starts late in fetal life and lasts to about 1–1.5 years postnatally, and 2) microvascular maturation that starts during the first few months of postnatal life and continues through to the age of 2–3 years (Massaro, Massaro, & Chambon, 2004). These processes are fine-tuned to occur within normal O2 ranges, but they can be disrupted by high O2 levels when infants are supported by supra-ambient O2. Furthermore, in prematurity, the lung has not developed sufficiently to transition to room air. This presents additional challenges because, not only are the lungs underdeveloped, but they are more often than not, injured by mechanical forces in addition to supplemental O2.

The nervous system also undergoes substantial postnatal development. Indeed, activity of the nervous system is an important influence on its development; for example, stimuli are important for both refinement of dendrites and myelination of axons on neurons (Etxeberria et al., 2016). In this mini review, we will focus on myelination. Myelination is the process of insulating axons with fatty material that allows electrical impulses to move efficiently (Zalc & Rosier, 2018). This is critical for vision, learning and movement. Myelination begins antenatally on some axons of the central nervous system (CNS), but mostly happens postnatally when subcortical and cortical axons become myelinated in a posterior to anterior direction. This developmental process begins with neural stem cells (NSCs) within germinal zones differentiating into progenitors committed to the oligodendroglial fate, followed by proliferation and then migration of these cells to their ultimate location where they differentiate into mature oligodendrocytes capable of identifying axons and enwrapping them with myelin sheaths (Elbaz & Popko, 2019). O2 levels, as we will describe in greater detail below, are critically important in the differentiation of these cells in the brain. So, disruption of normal postnatal O2 levels in the brain can deleteriously affect NSC and oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) differentiation and development, resulting in NDI.

O2 saturations (sO2) and O2 tensions (pO2) are higher in blood compared to brain and differ in rodents as compared to humans. For example, rodent arterial blood sO2 is 12% (pO2 95mmHg), while rodent brain sO2 ranges 0.1–5.3%, (pO2 0.8–40 mmHg) (Silver & Erecinska, 1998; Stacpoole et al., 2013). By comparison, human venous cord blood sO2 is 56%, (pO2 27mmHg), while human arterial cord blood sO2 is 36%, ( pO2 23mmHg) (Di Tommaso, Seravalli, Martini, La Torre, & Dani, 2014). Fetal human brain sO2 and pO2 both would be expected to be lower than values measured in human venous cord blood and higher than in human arterial cord blood. Using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to measure sO2 in human fetuses during labor, cerebral sO2 was measured at 43% ± 10% (Peebles et al., 1992). In a recent NIRS study, the human newborn frontoparietal cortex median sO2 at 3min of life was 46%, plateauing at 65.6% after 10min of life (De Carli et al., 2019). While we do not know the sO2 of less superficial human brain regions, rodent studies indicate that the pO2 in cortical white matter is much lower than in cortical gray matter (6–16mmHg versus 19–40mmHg) (Silver & Erecinska, 1998; Stacpoole et al., 2013). In other areas such as the pons, midbrain and subcortical white matter, pO2 is even lower ranging from 0.8–16mmHg. For this reason it is likely that pathways activated by low oxygen levels, such as the HIFs (hypoxia inducible factors), play an important role in normal white matter development (Brill, Scheuer, Buhrer, Endesfelder, & Schmitz, 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). Thus, normal brain development takes place in varying concentrations of O2 that are typically much lower than the 56% O2 found in oxygenated fetal blood or 21% in which cells are cultured in the lab. These studies suggest that O2 may be more available in humans compared to rodents, yet sO2 within human white matter has not been measured. This is a knowledge gap in the field.

4. Oxygen levels impact the differentiation of oligodendroglial cells.

Postnatal oligodendroglial progenitor cells (OPCs) are derived from multipotential NSCs in the subventricular zone and subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus. Once committed to the oligodendroglial lineage, cells further differentiate into pre-oligodendrocytes (preOL) and mature OL. This lineage has been shown to be influenced by O2 availability (Fig 2).

Figure 2: The effects of oxygen exposure on oligodendroglial cells.

The top line of the figure indicates that cultured cells have been tested at ranges from physiological (1–5% O2) to hyperoxic (80% O2). In vivo studies lie somewhere in between, as it is not known what O2 tensions exist in tissues of mice reared in high oxygen (75–85% O2). The triangle with the blue to red gradient represents the O2 gradient. Below this is the summary of the findings of the cell culture studies under hypoxia, room air and hyperoxia. Below this, positioned between room air and 80% O2 is the summary of in vivo studies.

In general, higher O2 levels are consistent with alteration of the timing of lineage commitment and apoptosis. For example, cultured rat NSCs were initially inhibited from differentiation into OPCs when cultured in room air, yielding fewer preOLs (marked by O4 antibody) after 5 days in vitro (DIV) compared to those cultured in hypoxia (3% O2) (Stacpoole et al., 2013). However, after 28 DIV, NSCs cultured in room air (21% O2) yielded more preOLs and mature OLs (marked by MBP (myelin basic protein)) and fewer neural progenitor cells (marked by NG2 (neural/glial antigen 2)), and fewer OPCs (marked by PDGFRα (platelet derived growth factor α)), suggesting that most of the OPCs had differentiated at that time point. Culture of rat NSCs at 3% O2, which is more equivalent to levels in the subcortical white matter, improved the viability of these cells when transplanted back into rat brains; these cells differentiated into OLs at a greater rate following transplantation as compared to NSCs cultured at 20% (Stacpoole et al., 2013).

Similar findings to those observed in NSCs were also observed in OPCs. In primary rat OPC cultures, culture in room air downregulated Olig1 (oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2), Sox9 (SRY-related HMG box 9), Sox10 (SRY-related HMG box 10), CNP (2’,3’-cyclic nucleotide 3’ phosphodiesterase) and MBP (myelin basic protein) compared to culture in 5% O2. However, when apoptosis was examined in OPCs, it was only modestly increased in room air compared to 5% O2, and this was not statistically significant (Brill et al., 2017). Gerstner and colleagues studied the effects of hyperoxia on cultured rat OPCs (Gerstner et al., 2006; Gerstner et al., 2008). They found that apoptosis was significantly increased in preOLs when cells were cultured for 6–24h in 80% O2, but this was not surprising given the large increase in O2 exposure. Interestingly, mature OLs were not affected by increased apoptosis. Inhibition of caspases and induced expression of BCL-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) protected preOLs from apoptosis at 80% O2. Cultures exposed to 80% O2 generated mitochondrially-derived reactive O2 species including superoxide, demonstrated by the fluorophores MitoSOX and DCFDA. Mimics of catalase, superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase decreased cell death. When the effects of hyperoxia were tested in vivo, the authors observed that MBP was reduced after 24h of 80% FiO2 at postnatal day (P) 3 and P6. Increased O2 for 24h at P11 did not alter MBP significantly. While this study highlighted the effects of culturing OPCs at very high O2 levels, the most important finding here was that relatively short periods of high O2 exposure can alter white matter development in the perinatal period in vivo. A third study by Gerstner and colleagues examined the effects of very high O2 on cultured OPCs and the oligodendroglial cell line OLN-93 (Gerstner et al., 2007). Here, the authors reported that 17β-estradiol protected OLN-93 cells from apoptosis by preventing increased Fas signaling, suggesting that sex plays a role in the vulnerability to high O2. 17β-estradiol also reduced the effects of hyperoxia on MBP, supporting the hypothesis that female sex hormone can protect white matter from hyperoxia induced injury. It is interesting that in these studies the authors did not report any increases in apoptosis in vivo. It may be that their cultured cells were exposed to much higher concentrations of O2 than their in vivo counterparts. Their observations are consistent with those of Brill et al., who did not observe apoptosis in OPCs cultured at 21% O2 (Brill et al., 2017).

Of the several studies that have been performed in vivo, most have used P6 rat pups exposed to 80% FiO2 for 24h. These studies replicated losses of preOLs and immature OLs seen in cell culture experiments (Gerstner et al., 2006; Gerstner et al., 2007). They also showed that onset of the insult is important: hyperoxia at P3 and P6, but not P10, caused white matter injury (Gerstner et al., 2008). Duration of the insult was also important: 12h of 80% FiO2 at P7 caused degeneration of cells in white matter tracts (Felderhoff-Mueser et al., 2004); 48h of 80% FiO2 at P6, caused only transient loss of NG2+ cells, CC1+ (Quaking 7) cells and MBP, yet MRI revealed decreased fractional anisotropy at P60 (Schmitz et al., 2011). Another study using the same model showed no change in CNP, but transient loss of MAG (myelin-associated glycoprotein), MOG (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein), PLP (proteolipid protein) and myelin thickness. With regards to persistent changes, increased extra-myelin loops, decreased Caspr (contactin-associated protein) pairs, increased distance between Caspr pairs, decreased Caspr spread and fewer node-paranode regions were observed after hyperoxia at P60. Corpus callosal electrophysiologic field recordings (M wave and UM wave amplitude and velocity) were also decreased at P60 (Ritter et al., 2013). Together these studies suggest that short exposures to hyperoxia result in transient losses of OPCs, more mature OLs and myelin proteins. However, these findings demonstrate that defects in myelin structure and function may persist. In other words, short exposures to hyperoxia disrupt myelination of axons but not progenitor differentiation.

The effects of more clinically relevant chronic hyperoxia exposure on oligodendroglia in animals are poorly understood as there are only 5 published studies. Goren at al., (2017) treated rat pups raised for five days (from P0 to P5) in 80% FiO2 with the glycosylated pyrimidine-analog uridine and found that uridine conferred neuroprotection (Goren et al., 2017). Uridine treatment prevented hyperoxia-induced loss of corpus callosum thickness, loss of MBP at P5 and decreased latency in the Morris Water Maze probe test at P39 through inhibition of apoptosis and inhibition of histone deacetylase (Goren et al., 2017). Thus, 5 days of hyperoxia is sufficient to induce a learning phenotype.

Vottier et al., (2011) found that rat exposed to hypoxia during fetal life (10% FiO2 from E5 to E21), then chronic hyperoxia for seven days (60% FiO2 from E21 to P7) compared to progressive oxygenation (15% FiO2 E21 to 21% FiO2 at P7) had decreased myelin content and fewer mature oligodendrocytes by P10 (Vottier et al., 2011). They also found that expression of PDGFRα, Sox10, and Nkx2.2 (NK2 homeobox 2) increased and Sema3A (Semaphorin 3A) and Sema3F (Semaphorin 3F), molecules that regulate OPC migration, decreased. While this model is not particularly clinically relevant, it nonetheless suggests that antenatal hypoxia prior to chronic hyperoxia could induce aberrantly timed OPC migration or oligodendroglial differentiation as mechanisms for WMI. This study did not look for effects beyond P10.

Pham et al., (2014) exposed rat pups to 80% FiO2 for seven days (P0-P7). Some rats were treated concurrently to inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) 5ppm from E21 to P7 (Pham et al., 2014). Chronic hyperoxia alone resulted in decreased cell proliferation at P3 and P10, decreased NG2+ and O4+ cells at P3, decreased APC+ (Adenomatous polyposis coli protein) and MBP staining as well as increased GFAP+ (Glial fibrillar acidic protein) cells and increased TUNEL and CC3 (cleaved caspase 3) staining in white matter at P10, however, these findings did not persist at P21. Concurrent iNO treatment resulted in decreased microglia at P3, decreased TUNEL+ (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labelling) and CC3+ cells and protein at P3, and decreased GFAP at P10 in white mattter, compared to pups not treated with iNO. In addition, iNO increased proliferating NG2+ cells and decreased apoptotic O4+ cells at P3, and increased APC+ cells and MBP at P10 compared to untreated controls. iNO also improved internal carotid artery blood flow and improved learning as assessed by odor preference conditioning. This study suggested that iNO was neuroprotective, through an undefined mechanism. Thus, seven days of hyperoxia does not cause persistent effects through P21.

Other therapeutic interventions tested in acutely and chronically hyperoxic animals give clues to the O2-based mechanisms that cause WMI. Du et al., (2017) treated neonatal mice from P3-P5 with 80% FiO2 and analyzed MBP as a surrogate for white matter in the CNS at P12 (Du et al., 2017). They found that MBP levels were reduced in the hyperoxia group and that pre-treatment with the gamma secretase inhibitor DAPT rescued this. This finding suggests that Notch inhibition of OPC maturation may be involved in white matter cell response to hyperoxia (Du et al., 2017). Serdar et al., (2018) reported that neuronal overexpression of the small GTPase Ras protected against hyperoxia-induced injury when neonatal mice were exposed to 24h 80% FiO2 at P6 (Serdar et al., 2018). These included hyperoxia induced increases in non-myelinated axons, axons with increased adnexal space and axons with decompacted myelin. The authors suggested that this implicated MAPK/p-ERK (mitogen-activated protein kinase/phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinase) signaling from neurons in WMI, but they did not directly test this (Serdar et al., 2018). Scheuer and colleagues (2019) examined growth factor production by astrocytes in P6 rats treated with 80% FiO2 for 24h (Scheuer, Klein, Buhrer, Endesfelder, & Schmitz, 2019). This was combined with nasal administration of PDGFA (platelet derived growth factor A) to pups for 4d. Pups exposed to hyperoxia had reduced astrocyte expression of PDGFA, bFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor) and BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor). PDGFA treatment improved OPC cell proliferation and restored Olig1 expression through P7 and MBP expression through P11. These findings suggest that transient hyperoxia decreases growth factor production by astrocytes impacting oligodendroglial development directly (Scheuer et al., 2019).

Of these studies, only two are comparable to the model of BPD we use in our lab. This mouse model of BPD is well established and involves rearing litters in high O2 (75–85% FiO2) for two weeks. Exposure to hyperoxia is continuous with brief interruptions only for animal care (<10min/d). Dams are rotated with foster dams from hyperoxia to room air every 24–48h to prevent excessive oxygen toxicity to the adult animals. Litters are removed from the hyperoxia chamber at 14 days and allowed to recover in room air (Chang et al., 2018; K. J. Lee et al., 2014; Perez et al., 2017). This procedure results in an unambiguous BPD phenotype that also includes decreased alveolar vessel counts, right ventricular hypertrophy, increased pulmonary artery medial wall thickness, and disrupted cGMP signaling reminiscent of severe BPD with pulmonary hypertension (Chang et al., 2018; K. J. Lee et al., 2014; Perez et al., 2017).

Using this model in combination with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) as second variable or “hit” our lab showed persistent effects at P28, including decreased Olig2+ cells, decreased PDGFRα+ cells and decreased CC1+ cells, increased myelin G-ratio without change in axon diameter, and white matter tract volumes and length within corpus callosum and internal capsule by MRI and decreased motor function (Chang et al., 2018). In our model, thromboxane A2 analog administered to pregnant dams causes IUGR (Fung et al., 2011), whereas hyperoxia results in pathological changes similar to those seen in BPD and BPD-associated pulmonary hypertension (K. J. Lee et al., 2014). Placental under perfusion and hyperoxia may each affect the brain independently. Indeed, in the BPD alone group, significant differences were observed in oligodendroglial cell counts, MRI and motor function (Chang et al., 2018). IUGR combined with BPD reduced oligodendroglial cells from both early and late stages of the lineage. Myelin structure and white matter tracts were also reduced in IUGR pups with BPD. Our study provides further evidence that a second “hit” is exacerbates conditions for persistent WMI.

In a second study, Graf et al., (2014) combined 85% FiO2 from birth to P14 with antenatal lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment at E16 to induce maternal inflammation (Graf et al., 2014). Brains were examined at P14 and P28. The two insults resulted in decreased CNP at P14 that persisted through P28 in cerebral cortex in contrast to hyperoxia alone in which decreased CNP was observed only at P14. There was also increased accumulation of CC3 and increased microglial staining by Iba1 (ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1) at P14, in contrast to hyperoxia alone in which there were no increases in CC3 or Iba1 at P14 (Graf et al., 2014). This indicated that a heightened immune response could increase the effects of hyperoxia in white matter tracts. The study by Graf and colleagues also supports a “two-hit” or two factor mechanism leading to WMI and NDI. In the case of Graf’s study there is inflammation or an acute immune response. In the case of our study, there is the situation of very low birth weight. We therefore propose that the inflammatory response associated with BPD could act as an important second hit compounding the effects of hyperoxia caused by the use of oxygen to manage infants with BPD.

5. BPD and hyperoxia trigger immune responses that could injure the CNS parenchyma

Historically BPD was known to be a disease in which the immune response played a prominent role in the lung (Savani, 2018). This was supported by numerous studies in animal models that demonstrated the effects of inflammation on the lung after different types of lung injury including BPD. It followed that an inflammatory response caused by other situations such as infection could also worsen lung injury. For these reasons anti-inflammatory approaches have been used to improve outcomes in babies with BPD for decades (Balany & Bhandari, 2015; Papagianis, Pillow, & Moss, 2019; Speer, 2006). What has not been considered is that an immune response activated by lung injury could affect the CNS. Given the likely association between BPD and risk for NDI, we believe that there could be a systemic effect that modifies white matter development in particular and is separate from the direct effect of higher oxygen tensions in the brain resulting from O2 therapy (Fig 3). How could this happen?

Figure 3: Interaction of blood and the CNS in response to BPD.

A schematic drawing of possible effects of BPD on the BBB and oligodendroglial differentiation. The blood vessel is placed above and below the CNS parenchyma. Basement membranes (BM) are indicated above right. Hyperoxia and inflammation associated with BPD may activate monocytes which accumulate and weaken the BBB by an unknown mechanism. This could allow blood proteins such as fibrinogen to penetrate the CNS parenchyma. This could activate BMP signaling through the ACVR1/BMPR2 receptor and either arrest OPC differentiation or trigger OPCs to differentiate into astrocytes, as has been observed in vitro. Monocytes bind to activated endothelium more efficiently and could enter the CNS parenchyma through diapedesis. These cells, as well as microglia could also respond to fibrinogen via Mac-1 and this increases their production of cytokines such as IL1β. Monocytes, monocyte-derived macrophages and microglia also produce reactive O2 species (ROS) in response to hyperoxia that can cause axonal damage.

There are already clues emerging in the literature. As we discussed before, infection or inflammation add a layer of complexity to the common mechanistic themes of oligodendroglial injury observed in the in vitro and in vivo models. For example, LPS exposure prior to hyperoxia reduced CNPase staining and increased CC3 and Iba1 staining (Graf et al., 2014). This observation clearly implicates inflammation, and arrested maturation of OPCs as a response to increased O2 (Brehmer et al., 2012). A small number of studies support the idea that anti-inflammatory drugs can protect cells in white matter tracts after exposure to hyperoxia. Schmitz et al. (2014) subjected P6 rat pups to 80% FiO2 for 24h with and without the antibiotic minocycline, which has anti-inflammatory properties (Schmitz et al., 2014). Minocycline treatment protected the brain from apoptosis, improved cell proliferation and protected against loss of OL maturation. Importantly, minocycline inhibited microglial cell shape changes and microglial IL-1β production (Fig 3). Treatment of cultured microglial cells with minocycline reduced production of cytokines, supporting the idea that microglial activation downstream of hyperoxia is detrimental to white matter formation. Similar findings were obtained with Fingolimod, an anti-inflammatory sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator used to treat relapsing multiple sclerosis (Serdar et al., 2016). These studies support the idea that innate immunity is important in the response of the brain to hyperoxia. Other neurological disease models have shown that innate immune cells such as monocytes cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) to promote inflammation after injury. For example, Varvel et al. found a marked increase in monocytes in the brain in an animal model of status epilepticus (SE) (Varvel et al., 2016). Using a mouse that specifically marks circulating monocytes the authors’ showed that no cells infiltrated the CNS in healthy mice, but many cells entered the brain after SE. Studies such as this indicate that monocytes, in particular, enter the CNS parenchyma in pathological or injured states. It will therefore be of interest to investigate if monocytes cross the BBB in animal models of BPD.

Weakening the BBB may affect oligodendroglial differentiation and white matter development in other ways as suggested by the multiple sclerosis (MS) literature (Fig 3). Progressive active and chronic MS lesions accumulate the blood product fibrinogen (Vos et al., 2005; Yates et al., 2017). Marik et al. (2007) observed that fibrinogen accumulated in and preceded demyelination of MS lesions (Marik, Felts, Bauer, Lassmann, & Smith, 2007). Thus, evidence supports a role for fibrinogen in the neuropathology of MS and is not simply a marker for the disease. Davalos et al., (2012) using an experimental model of allergic encephalomyelitis and injection of fibrinogen into healthy mice, found that fibrinogen induced microglia to form perivascular clusters in and around the vasculature (Davalos et al., 2012). Injection of fibrinogen was sufficient to injure axons. Mutations targeting the αmβ2 (CD11b/CD18, Mac-1) integrin on microglia prevented this from happening demonstrating the direct role of fibrinogen in this process. Petersen et al. (2017) further investigated the mechanism through which fibrinogen affects oligodendrocyte differentiation (Petersen et al., 2017). They found that fibrinogen induced bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in cultured rat oligodendrocytes and this stimulated many of these cells to become astrocytes. Since this process was not inhibited by Noggin, which competitively inhibits BMP ligands, they deleted ACVR1/ALK2 (activin receptor 1/activin receptor-like kinase 2). This deletion interfered with induction of BMP signaling outputs, like phosphorylation of SMAD 1/5/8 and astrocyte differentiation, suggesting that fibrinogen, upon reaching oligodendroglia, induces the BMP signaling pathway through ACVR1 (Fig 3). In this pathway, the ligand (fibrinogen, activin or BMP) binds either ACVR2A, ACVR2B or BMPR2 (Bone morphogenetic receptor 2) which then forms a complex with ACVR1 to transduce the signal into the cell (Pauklin & Vallier, 2015). This triggers expression of genes known to regulate the lineage switch between myelin expressing oligodendrocytes and astrocytes such as Id1 (Inhibitor of differentiation 1), Id2 (Inhibitor of differentiation 2), Nog (Noggin), Hes1 (hairy and enhancer of split 1), Hey1 (Hes related with YPRW motif 1) and Lef1 (Lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1) (Sakamoto, Hirata, Ohtsuka, Bessho, & Kageyama, 2003). Presumably differential expression of these genes would affect uncommitted progenitors causing them to either arrest in the lineage or to inappropriately become astrocytes.

The evidence for weakening of the BBB in hyperoxia induced BPD is sparse and would be the next logical step to investigate. There is ample evidence that the lung undergoes inflammation and that anti-inflammatory drugs protect the lung in BPD, but it is not known if this inflammation results in a systemic effect that contributes to weakening of the BBB. However, the arrows are starting to point in that direction. First, there is the proposed link between BPD and increased risk for NDI. Second, we found that RNA-seq analysis of whole brain in the mouse BPD model identified increased expression of two genes involved in monocyte recruitment: CCL17 (chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2) and Cyr61/CCN1 (cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61/cellular communication network factor 1). These genes were included in the top twenty significantly upregulated genes (Chang et al., in resubmission). CCL17 is the soluble ligand of CCR4 (chemokine receptor 4), which is one of the chemokine receptors displayed on circulating monocytes (Scheu, Ali, Ruland, Arolt, & Alferink, 2017). It is secreted by macrophages involved in the induction of chemotaxis of various immune cells including Th2 (T helper 2) cells and monocytes. Presumably, increased expression of CCL17 could indicate a mechanism by which monocytes could be targeted to the brain. Differentiation of these cells into macrophages could amplify the recruitment of macrophages into the CNS parenchyma, similar to what was observed in EAE. Cyr61 is another surface receptor expressed by monocytes (Schober et al., 2002; Schober, Lau, Ugarova, & Lam, 2003). It binds to Mac-1, and this interaction facilitates binding of monocytes to target cells in various tissues and as we discussed above, mediates the effects of fibrinogen in the mouse model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (Davalos et al., 2012). Differential expression of these genes in the brain in response to BPD is consistent with the hypothesis that BPD induces an immune response in the brain and raises the possibility that the WMI injury we have observed is associated with this reaction.

6. Conclusions

While physicians have long recognized an association between prematurity and NDI, we have only recently begun to understand the intricacies of prematurity, normal development and the clinical interventions required to manage critically ill infants. Using a combination of human studies and animal models we now understand that O2 itself is a critical modulator of WMI, and in fact, white matter tracts have relatively low levels of O2 under normal circumstances. High levels of therapeutic O2 can damage white matter development and myelination and can trigger immune responses that can compound the effects on oligodendroglial cells. This may involve damaging the BBB, although this has yet to be directly tested. Given these hypotheses, and the usual requirement of O2 therapy for critically ill or premature infants, managing the immune response may be the most effective way to limit WMI and NDI in this at-risk population.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

Babies born prematurely or with other conditions such as lung disease are at high risk for neurodevelopmental impairment. Some of these patients have white matter injury leading to abnormal myelination and motor skills. Typically, infants in neonatal intensive care units are given supplemental oxygen. However, an increasing number of studies have implicated high oxygen as damaging myelination. Here we discuss this emerging field of study and how lung disease may be related to white matter injury. We discuss the compounding effect of the immune response and how this could be the key to protecting the brain from hyperoxic injury.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no competing financial interests. M.L.V.D. was supported by NINDS R01NS086945.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Data sharing statement: Data sharing is not applicable in this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study

References

- Bairoliya N, & Fink G (2018). Causes of death and infant mortality rates among full-term births in the United States between 2010 and 2012: An observational study. PLoS Med, 15(3), e1002531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balany J, & Bhandari V (2015). Understanding the Impact of Infection, Inflammation, and Their Persistence in the Pathogenesis of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Front Med (Lausanne), 2, 90. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2015.00090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaino G, Khoshnood B, Kaminski M, Pierrat V, Marret S, Matis J, . . . Group ES (2010). Predictors of cerebral palsy in very preterm infants: the EPIPAGE prospective population-based cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol, 52(6), e119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03612.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehmer F, Bendix I, Prager S, van de Looij Y, Reinboth BS, Zimmermanns J, . . . Gerstner B (2012). Interaction of inflammation and hyperoxia in a rat model of neonatal white matter damage. PLoS One, 7(11), e49023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill C, Scheuer T, Buhrer C, Endesfelder S, & Schmitz T (2017). Oxygen impairs oligodendroglial development via oxidative stress and reduced expression of HIF-1alpha. Sci Rep, 7, 43000. doi: 10.1038/srep43000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne PJ, Piper MC, & Darrah J (1989). Motor development at term of very low birthweight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol, 9(3), 301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JL, Bashir M, Santiago C, Farrow K, Fung C, Brown AS, . . . Dizon MLV (2018). Intrauterine Growth Restriction and Hyperoxia as a Cause of White Matter Injury. Dev Neurosci, 40(4), 344–357. doi: 10.1159/000494273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos D, Ryu JK, Merlini M, Baeten KM, Le Moan N, Petersen MA, . . . Akassoglou K (2012). Fibrinogen-induced perivascular microglial clustering is required for the development of axonal damage in neuroinflammation. Nat Commun, 3, 1227. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LM, & Berkelhamer SK (2017). Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Chronic Lung Disease of Infancy and Long-Term Pulmonary Outcomes. J Clin Med, 6(1). doi: 10.3390/jcm6010004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carli A, Andresen B, Giovannella M, Durduran T, Contini D, Spinelli L, . . . Greisen G (2019). Cerebral oxygenation and blood flow in term infants during postnatal transition: BabyLux project. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 104(6), F648–F653. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-316400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tommaso M, Seravalli V, Martini I, La Torre P, & Dani C (2014). Blood gas values in clamped and unclamped umbilical cord at birth. Early Hum Dev, 90(9), 523–525. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du M, Tan Y, Liu G, Liu L, Cao F, Liu J, . . . Xu Y (2017). Effects of the Notch signalling pathway on hyperoxia-induced immature brain damage in newborn mice. Neurosci Lett, 653, 220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.05.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz B, & Popko B (2019). Molecular Control of Oligodendrocyte Development. Trends Neurosci, 42(4), 263–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etxeberria A, Hokanson KC, Dao DQ, Mayoral SR, Mei F, Redmond SA, . . . Chan JR (2016). Dynamic Modulation of Myelination in Response to Visual Stimuli Alters Optic Nerve Conduction Velocity. J Neurosci, 36(26), 6937–6948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0908-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehlings D (2017). Pain in cerebral palsy: a neglected comorbidity. Dev Med Child Neurol, 59(8), 782–783. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felderhoff-Mueser U, Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Jarosz B, Korobowicz E, Mahler L, . . . Ikonomidou C (2004). Oxygen causes cell death in the developing brain. Neurobiol Dis, 17(2), 273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung C, Brown A, Cox J, Callaway C, McKnight R, & Lane R (2011). Novel thromboxane A2 analog-induced IUGR mouse model. J Dev Orig Health Dis, 2(5), 291–301. doi: 10.1017/S2040174411000535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstner B, Buhrer C, Rheinlander C, Polley O, Schuller A, Berns M, . . . Felderhoff-Mueser U (2006). Maturation-dependent oligodendrocyte apoptosis caused by hyperoxia. J Neurosci Res, 84(2), 306–315. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstner B, DeSilva TM, Genz K, Armstrong A, Brehmer F, Neve RL, . . . Rosenberg PA (2008). Hyperoxia causes maturation-dependent cell death in the developing white matter. J Neurosci, 28(5), 1236–1245. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3213-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstner B, Sifringer M, Dzietko M, Schuller A, Lee J, Simons S, . . . Felderhoff-Mueser U (2007). Estradiol attenuates hyperoxia-induced cell death in the developing white matter. Ann Neurol, 61(6), 562–573. doi: 10.1002/ana.21118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren B, Cakir A, Sevinc C, Serter Kocoglu S, Ocalan B, Oy C, . . . Cansev M (2017). Uridine treatment protects against neonatal brain damage and long-term cognitive deficits caused by hyperoxia. Brain Res, 1676, 57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf AE, Haines KM, Pierson CR, Bolon BN, Houston RH, Velten M, . . . Rogers LK (2014). Perinatal inflammation results in decreased oligodendrocyte numbers in adulthood. Life Sci, 94(2), 164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham HK, Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Dan B, Lin JP, Damiano DL, . . . Lieber RL (2016). Cerebral palsy. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2, 15082. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintz SR, Kendrick DE, Wilson-Costello DE, Das A, Bell EF, Vohr BR, . . . Network, N. N. R. (2011). Early-childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes are not improving for infants born at <25 weeks’ gestational age. Pediatrics, 127(1), 62–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintz SR, Van Meurs KP, Perritt R, Poole WK, Das A, Stevenson DK, . . . Network, N. N. R. (2007). Neurodevelopmental outcomes of premature infants with severe respiratory failure enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of inhaled nitric oxide. J Pediatr, 151(1), 16–22, 22 e11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng SF, Hsu CH, Tsao PN, Chou HC, Lee WT, Kao HA, . . . Hsieh WS (2008). Bronchopulmonary dysplasia predicts adverse developmental and clinical outcomes in very-low-birthweight infants. Dev Med Child Neurol, 50(1), 51–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.02011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Salamon M, Gerner EM, Jonsson B, & Lagercrantz H (2000). Early motor and mental development in very preterm infants with chronic lung disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 83(1), F1–6. doi: 10.1136/fn.83.1.f1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurinczuk JJ, White-Koning M, & Badawi N (2010). Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev, 86(6), 329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Choi YH, Hong J, Kim NY, Kim EB, Lim JS, . . . Lee HJ (2019). Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Is Associated with Altered Brain Volumes and White Matter Microstructure in Preterm Infants. Neonatology, 116(2), 163–170. doi: 10.1159/000499487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Berkelhamer SK, Kim GA, Taylor JM, O’Shea KM, Steinhorn RH, & Farrow KN (2014). Disrupted pulmonary artery cyclic guanosine monophosphate signaling in mice with hyperoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 50(2), 369–378. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0118OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malavolti AM, Bassler D, Arlettaz-Mieth R, Faldella G, Latal B, & Natalucci G (2018). Bronchopulmonary dysplasia-impact of severity and timing of diagnosis on neurodevelopment of preterm infants: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Paediatr Open, 2(1), e000165. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marik C, Felts PA, Bauer J, Lassmann H, & Smith KJ (2007). Lesion genesis in a subset of patients with multiple sclerosis: a role for innate immunity? Brain, 130(Pt 11), 2800–2815. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro D, Massaro GD, & Chambon P (2004). Lung development and regeneration. New York: Marcel Dekker. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, Birbeck G, Burstein R, Chou D, . . . Collaborators, U. S. B. o. D. (2013). The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA, 310(6), 591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northway WH Jr., Rosan RC, & Porter DY (1967). Pulmonary disease following respirator therapy of hyaline-membrane disease. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med, 276(7), 357–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196702162760701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagianis PC, Pillow JJ, & Moss TJ (2019). Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Pathophysiology and potential anti-inflammatory therapies. Paediatr Respir Rev, 30, 34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh NA, Sharma P, He L, Li H, Altaye M, Priyanka Illapani VS, & Investigators, C. I. N. E. P. S. C. (2020). Perinatal Risk and Protective Factors in the Development of Diffuse White Matter Abnormality on Term-Equivalent Age Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Infants Born Very Preterm. J Pediatr. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauklin S, & Vallier L (2015). Activin/Nodal signalling in stem cells. Development, 142(4), 607–619. doi: 10.1242/dev.091769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peebles DM, Edwards AD, Wyatt JS, Bishop AP, Cope M, Delpy DT, & Reynolds EO (1992). Changes in human fetal cerebral hemoglobin concentration and oxygenation during labor measured by near-infrared spectroscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 166(5), 1369–1373. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91606-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez M, Lee KJ, Cardona HJ, Taylor JM, Robbins ME, Waypa GB, . . . Farrow KN (2017). Aberrant cGMP signaling persists during recovery in mice with oxygen-induced pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One, 12(8), e0180957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman JM, & Volpe JJ (1989). Movement disorder of premature infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a new syndrome. Pediatrics, 84(2), 215–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perra O, Rankin J, Platt MJ, Sellier E, Arnaud C, De La Cruz J, . . . Bjellmo S (2020). Decreasing cerebral palsy prevalence in multiple births in the modern era: a population cohort study of European data. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-318950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen MA, Ryu JK, Chang KJ, Etxeberria A, Bardehle S, Mendiola AS, . . . Akassoglou K (2017). Fibrinogen Activates BMP Signaling in Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells and Inhibits Remyelination after Vascular Damage. Neuron, 96(5), 1003–1012 e1007. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham H, Vottier G, Pansiot J, Duong-Quy S, Bollen B, Dalous J, . . . Baud O (2014). Inhaled NO prevents hyperoxia-induced white matter damage in neonatal rats. Exp Neurol, 252, 114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter J, Schmitz T, Chew LJ, Buhrer C, Mobius W, Zonouzi M, & Gallo V (2013). Neonatal hyperoxia exposure disrupts axon-oligodendrocyte integrity in the subcortical white matter. J Neurosci, 33(21), 8990–9002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5528-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse DJ, Hirtz DG, Thom E, Varner MW, Spong CY, Mercer BM, . . . Eunice Kennedy Shriver NM-FMUN (2008). A randomized, controlled trial of magnesium sulfate for the prevention of cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med, 359(9), 895–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph AM (1991). Rudolph’s pediatrics (19th ed.). Norwalk, Conn.: Appleton & Lange. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M, Hirata H, Ohtsuka T, Bessho Y, & Kageyama R (2003). The basic helix-loop-helix genes Hesr1/Hey1 and Hesr2/Hey2 regulate maintenance of neural precursor cells in the brain. J Biol Chem, 278(45), 44808–44815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300448200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savani RC (2018). Modulators of inflammation in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Semin Perinatol, 42(7), 459–470. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheu S, Ali S, Ruland C, Arolt V, & Alferink J (2017). The C-C Chemokines CCL17 and CCL22 and Their Receptor CCR4 in CNS Autoimmunity. Int J Mol Sci, 18(11). doi: 10.3390/ijms18112306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuer T, Klein LS, Buhrer C, Endesfelder S, & Schmitz T (2019). Transient Improvement of Cerebellar Oligodendroglial Development in a Neonatal Hyperoxia Model by PDGFA Treatment. Dev Neurobiol, 79(3), 222–235. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz T, Krabbe G, Weikert G, Scheuer T, Matheus F, Wang Y, . . . Endesfelder S (2014). Minocycline protects the immature white matter against hyperoxia. Exp Neurol, 254, 153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz T, Ritter J, Mueller S, Felderhoff-Mueser U, Chew LJ, & Gallo V (2011). Cellular changes underlying hyperoxia-induced delay of white matter development. J Neurosci, 31(11), 4327–4344. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3942-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober JM, Chen N, Grzeszkiewicz TM, Jovanovic I, Emeson EE, Ugarova TP, . . . Lam SC (2002). Identification of integrin alpha(M)beta(2) as an adhesion receptor on peripheral blood monocytes for Cyr61 (CCN1) and connective tissue growth factor (CCN2): immediate-early gene products expressed in atherosclerotic lesions. Blood, 99(12), 4457–4465. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober JM, Lau LF, Ugarova TP, & Lam SC (2003). Identification of a novel integrin alphaMbeta2 binding site in CCN1 (CYR61), a matricellular protein expressed in healing wounds and atherosclerotic lesions. J Biol Chem, 278(28), 25808–25815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301534200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serdar M, Herz J, Kempe K, Lumpe K, Reinboth BS, Sizonenko SV, . . . Bendix I (2016). Fingolimod protects against neonatal white matter damage and long-term cognitive deficits caused by hyperoxia. Brain Behav Immun, 52, 106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serdar M, Herz J, Kempe K, Winterhager E, Jastrow H, Heumann R, . . . Bendix I (2018). Protection of Oligodendrocytes Through Neuronal Overexpression of the Small GTPase Ras in Hyperoxia-Induced Neonatal Brain Injury. Front Neurol, 9, 175. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver I, & Erecinska M (1998). Oxygen and ion concentrations in normoxic and hypoxic brain cells. Adv Exp Med Biol, 454, 7–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4863-8_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer CP (2006). Pulmonary inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol, 26 Suppl 1, S57–62; discussion S63–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacpoole SR, Webber DJ, Bilican B, Compston A, Chandran S, & Franklin RJ (2013). Neural precursor cells cultured at physiologically relevant oxygen tensions have a survival advantage following transplantation. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2(6), 464–472. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, . . . Human Development Neonatal Research, N. (2015). Trends in Care Practices, Morbidity, and Mortality of Extremely Preterm Neonates, 1993–2012. JAMA, 314(10), 1039–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp M, Huusom LD, Langhoff-Roos J, Delhumeau C, Hutton JL, Dolk H, & Group, S. C. (2004). Multiple birth and cerebral palsy in Europe: a multicenter study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 83(6), 548–553. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Naarden Braun K, Doernberg N, Schieve L, Christensen D, Goodman A, & Yeargin-Allsopp M (2016). Birth Prevalence of Cerebral Palsy: A Population-Based Study. Pediatrics, 137(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvel NH, Neher JJ, Bosch A, Wang W, Ransohoff RM, Miller RJ, & Dingledine R (2016). Infiltrating monocytes promote brain inflammation and exacerbate neuronal damage after status epilepticus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 113(38), E5665–5674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604263113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos CM, Geurts JJ, Montagne L, van Haastert ES, Bo L, van der Valk P, . . . de Vries HE (2005). Blood-brain barrier alterations in both focal and diffuse abnormalities on postmortem MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis, 20(3), 953–960. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vottier G, Pham H, Pansiot J, Biran V, Gressens P, Charriaut-Marlangue C, & Baud O (2011). Deleterious effect of hyperoxia at birth on white matter damage in the newborn rat. Dev Neurosci, 33(3–4), 261–269. doi: 10.1159/000327245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Costello D (2007). Is there evidence that long-term outcomes have improved with intensive care? Semin Fetal Neonatal Med, 12(5), 344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2007.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates RL, Esiri MM, Palace J, Jacobs B, Perera R, & DeLuca GC (2017). Fibrin(ogen) and neurodegeneration in the progressive multiple sclerosis cortex. Ann Neurol, 82(2), 259–270. doi: 10.1002/ana.24997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younge N, Goldstein RF, Bann CM, Hintz SR, Patel RM, Smith PB, . . . Human Development Neonatal Research, N. (2017). Survival and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes among Periviable Infants. N Engl J Med, 376(7), 617–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalc B, & Rosier F (2018). Myelin : the brain’s supercharger. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Kim B, Zhu X, Gui X, Wang Y, Lan Z, . . . Guo F (2020). Glial type specific regulation of CNS angiogenesis by HIFα-activated different signaling pathways. Nat Commun, 11(1), 2027. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15656-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.