Abstract

Periostin is a matricellular protein important in regulating bone, tooth, and cardiac development. In pathologic conditions, periostin drives allergic and fibrotic inflammatory diseases and is also overexpressed in certain cancers. Periostin signaling in tumors has been shown to promote angiogenesis, metastasis, and cancer stem cell survival in rodent models, and its overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in human glioblastoma. However, the role of periostin in regulating tumorigenesis of canine cancers has not been evaluated. Given its role in bone development, we sought to evaluate mRNA and protein expression of periostin in canine osteosarcoma (OS) and assess its association with patient outcome. We validated an anti-human periostin antibody cross-reactive to canine periostin via western blot and immunohistochemistry and evaluated periostin expression in microarray data from 49 primary canine OS tumors and 8 normal bone samples. Periostin mRNA was upregulated greater than 40-fold in canine OS tumors compared to normal bone and was significantly correlated with periostin protein expression based on quantitative image analysis. However, neither periostin mRNA nor protein expression were associated with time to metastasis in this cohort. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis demonstrated significant enhancement of pro-tumorigenic pathways including canonical WNT signaling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and angiogenesis in periostin-high tumors, while periostin-low tumors demonstrated evidence of heightened antitumor immune responses. Overall, these data identify a novel antibody that can be used as a tool for evaluation of periostin expression in dogs and suggest that investigation of Wnt pathway-targeted drugs in periostin overexpressing canine OS may be a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: osteosarcoma, dogs, periostin, immunohistochemistry, gene expression

Periostin, or osteoblast-specific factor 2 (OSF-2), is a multifunctional matricellular protein with an important role in regulating normal bone, tooth, lung, and cardiac tissue development.12,26,77 The protein has been shown to be important in cardiac mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to support early valvulogenesis.70 In development, periostin has been shown to induce collagen fibrillogenesis, increasing the integrity of the ventricular wall.13 Periostin has also been described to be important in neonatal lung remodeling and alveolar simplification, with periostin expression to be increased in mice and infants with hyperoxic lung injury.5 Pathologically, aberrant expression of periostin is associated with a variety of inflammatory processes, such as pulmonary fibrosis, cancer, and asthmatic and allergic airway inflammation.36,47,55,78

On initial characterization of periostin, it was noted that the protein has distinct homology to the insect protein fasciclin I, an adhesion protein found to play an important role in neuronal development.18,76,83,87 This protein contains 4 fasciclin-like domains (FAS1 domains) that are responsible for interacting with various integrin receptors. Indeed, similar to its insect homologue, periostin functions as more than just a structural protein and also binds various integrin receptors (namely, αvβ3 and αvβ5) to modulate cell behavior.25,69,76 Periostin is known to activate numerous signal transduction pathways including focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)/Akt, pathways which have all been implicated in cancer development and are known to be important for angiogenesis and cellular survival, proliferation, and migration.1,8,12,25,32,45,49,59,69,75,84

The role of periostin in cancer has been evaluated in a variety of human cancers. Elevated periostin levels in tumor tissue or blood serum compared to healthy tissue has been demonstrated in breast,1,45 ovarian,25,75,85 glioblastoma,49,59,84 colon,1,2 and many other types of cancers.42,53 Periostin overexpression in these cancers is associated with increased biological aggressiveness and worse clinical outcome. Pro-tumorigenic functions demonstrated in human in vitro cell models and rodent preclinical models include periostin enhancement of invasion, metastasis, cancer stem cell survival, angiogenesis, and tumor growth.1,2,25,42,45,49,53,59,69,75,84,85 Yet very few studies have evaluated the role of periostin in osteosarcoma (OS),6,32,33 despite first being described in this cancer.76

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone cancer found in humans50,56 and dogs.15,60 Roughly 20% of human OS patients will have detectable pulmonary metastases at the time of initial diagnosis,37,50,56 with the likelihood of subsequent development of micrometastases in those patients initially free of distant disease remaining very high. Micrometastatic tumor cells can be present in the bone marrow and blood of 70% of individuals with no signs of metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis,7 and approximately 25% of all patients will eventually develop pulmonary metastases despite treatment with surgery and standard-of-care chemotherapy.7 Patients with lung metastases have a 30% 5-year survival,50,56 which has not improved in over 30 years. Thus, investigations into new model systems and treatments, specifically to stop development and progression of pulmonary metastasis, are desperately needed to improve the outcome of OS patients.21,39

Dogs with OS provide a unique opportunity to study this disease due to the high rate of natural occurrence in this species and similarity of the disease between humans and dogs.15,16,19,50,52,56 Canine OS occurs at greater than a 10-times higher rate than humans, with an incidence ranging from 7.9 to 13.3 per 100 000 dogs16,64 compared to adolescent human OS at 4.5 per 1 000 000 children.50,56 Canine OS shares many characteristics with human OS such as clinical behavior including primary tumor location, predilection for pulmonary metastasis and shared prognostic factors, as well as biological similarities including histological appearance and overlapping genomic and transcriptomic landscape.19,40,58,80 The use of canine OS as a model for human OS can provide a better understanding of the disease, and improve treatment and survival for both species.19,39,80 Already canine OS has been part of the development of novel surgical techniques and new therapies for their human counterpart.35,43,48,72,79,80

Given periostin’s role in normal bone development and correlation of its aberrant expression with many biological hallmarks of cancer progression across multiple tumor types, we hypothesized that periostin expression would be elevated in canine OS and that increased periostin would be associated with worse clinical outcome in canine OS patients. To investigate this, we validated an anti-human periostin antibody cross-reactive to canine periostin via western blot, immunocytochemistry, and immunohistochemistry. Utilizing formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) archived cases of canine OS and a previously generated microarray expression dataset associated with these cases, we evaluated mRNA and protein expression levels of periostin in a subset of 49 primary appendicular canine OS tumors and determined its association with patient progression-free survival. Furthermore, utilizing Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, we sought to determine whether periostin overexpression in canine OS was associated with in vivo enrichment of tumor-promoting biological functions similar to those previously reported for periostin in human and rodent cancer models.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Culture

Flint Animal Cancer Center (FACC) canine tumor cell lines were obtained from other institutions, purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), or established from tumor biopsy samples obtained at the FACC, as previously described.14,22 Tumor cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 units mL−1), and streptomycin (100 μg mL−1) and incubated under standard conditions at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2:95% air. Prior to expression profiling, all cell lines were confirmed to be mycoplasma-negative and the species of origin and cell line identity validated by polymerase chain region for short tandem repeat (STR) analysis.

Canine Osteosarcoma Primary Tumor Samples and Clinical Data

Treatment-naïve primary tumor samples were obtained from the Colorado State University (CSU) Flint Animal Cancer Center’s tissue archive. These patient samples are archived in compliance with the CSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee following obtainment of owner consent. Forty-nine tumors were selected based on clinical characteristics as described previously.57 Case selection was based on those primary appendicular OS tumors obtained from dogs treated only with surgical amputation followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and/or a platinum-based drug (choice of adjuvant drug has been shown to not result in significantly different survival times between treatment groups in previous studies).67 All dogs were free of lung metastases by thoracic radiographic analysis at diagnosis, and follow-up consisted of evaluation by clinical examinations including repeat thoracic radiographs every 2 to 3 months after initial treatment. For 8 of the appendicular OS tumor samples collected, samples of matched normal metaphyseal bone were also harvested from the same limb (at minimum separated by at least one joint space from the tumor) following amputation. Tumor and normal bone tissues collected at amputation were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C prior to downstream analysis.

Western Blot

The canine Moresco osteosarcoma cell line was used as a positive control for western blot validation of the manufacturer-reported canine cross-reactivity of the periostin antibody. The Moresco cell line was provided by Dawn Duval (Flint Animal Cancer Center) and was originally obtained from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Cells were cultured as described above and then supernatants collected as well as cell lysates generated by incubation of flasks with protein extraction buffer: 7 ml M-PER (ThermoFisher), 140 mg sodium dodecyl sulfate (ThermoFisher), 70 μl of 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (ThermoFisher), 35 μl of 200 mM sodium orthovanadate (Sigma-Aldrich), and ½ tablet Complete Mini protease inhibitor (Roche) for 5 minutes on ice. Lysates were removed from the flasks, triturated on ice using a pipette, centrifuged at 13 000 rpm for 5 minutes, and supernatant removed for protein concentration determination using a BCA protein assay (Pierce).

Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Protein was then wet transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) in a 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline Tween 20 solution (TBST). Membranes were then incubated with the primary antibody (rabbit anti-canine periostin, LifeSpan Bio, LS-B3986) diluted 1:1000 (1 μg/ml) in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST, overnight at 4 °C. The following day, membranes were rinsed (×3 with TBST), incubated with the secondary antibody (HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG; Thermo Scientific) diluted 1:3000 in 5% milk-TBST for 1 hour at RT. Membranes were rinsed again (×3 with TBST). Last, membranes were imaged with chemiluminescent substrate (Clarity Western ECL, BioRad) using a Chemi Doc XES + system (BioRad).

Immunohistochemistry and Immunocytochemistry

FFPE tumor tissue blocks were sectioned at 5 μm and mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific) for periostin immunolabeling. Briefly, tissue slides were deparaffinized in xylenes and rehydrated using a series of graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was performed using 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 20 minutes at 125 °C in a DAKO PT link module. For immunocytochemistry, cultured Moresco tumor cells were immobilized on to Superfrost Plus slides using a cytocentrifuge and subsequently fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde prior to commencing with immunolabeling, using the same autostainer and protocol for FFPE tumor tissue, as follows. Immunolabeling was performed using a Dako autostainer link 48. Tissues were blocked for endogenous peroxidase by incubation in 3% H2O2 for 5 minutes. Subsequently, sections were then incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-canine periostin primary antibody (Life-Span Biosciences, LS-B3986; 2.5 μg/ml) for 1 hour at RT. Bound primary antibody was detected using the universal labeled streptavidin-biotin2 system (Dako), which consists of incubation with a mixture of biotinylated goat anti-mouse and rabbit IgG secondary antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase–labeled streptavidin. Positive staining was visualized using DAB chromogen substrate (Dako). Purified rabbit immunoglobulin (Dako) was used in place of the primary antibody as a negative control to ascertain nonspecific labeling. Slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma Aldrich).

Image Analysis

For quantification of periostin immunoreactivity, five 400× magnification, intratumoral independent fields of each primary tumor were captured using standardized exposure times and a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope and Olympus DP70 camera. Representative tumor fields digitally captured for quantitative image analysis of periostin immunolabeling were chosen based on regions of highest expression. Five nonoverlapping 400× magnification images were captured from these regions by an individual blinded to clinical outcome or any other study data (ocular field number = 22 mm, total field of view area analyzed = 1.19 mm2). In order to ensure accurate quantitative assessment of periostin-positive immunolabeling, we used the color deconvolution algorithm developed for the NIH open source image analysis software, ImageJ. Using the H DAB (hematoxylin and DAB chromogen) vector for this algorithm, digitized intratumoral images of periostin immunolabeling were separated into 8-bit gray scale images representative of the chromogen color (DAB) only. A lower threshold limit was then set at a value corresponding to the mean of the isotype control, and universally applied to every single image. Any pixel value falling above this lower threshold value was measured as positive for periostin and used to determine % area positive within the field. For quality control, image masks of the “thresholded,” positive counted area were also generated and directly visually compared to the originally captured photomicrographs by a board-certified pathologist, to ensure accuracy in representation of periostin positive immunoreactivity and overall tumor area.

Gene Expression Microarray Analysis

Periostin expression across the FACC tumor cell line panel was evaluated using a microarray expression data set previously generated by the Duval Laboratory at the Flint Animal Cancer Center.22 For microarray analysis of the FACC tumor cell line panel, RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s protocol, as described previously.22 Quantity and quality of RNA was evaluated via a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and a Bioanalyzer (Agilent). RNA samples were then sent to the Genomics and Microarray Core at the University of Colorado. Briefly, samples were hybridized onto Affymetrix GeneChip Canine Genome 2.0 arrays, Canine Gene 1.0 ST arrays, and GeneChip miRNA 4.0 arrays. Resulting CEL files of expression data were then imported into Bioconductor,24 and intensity values were preprocessed with the Robust Multi-Array Average (RMA) algorithm.34

Evaluation of periostin expression in canine primary OS tumor samples and normal bone was done using microarray expression data also previously generated by the Duval Laboratory at the Flint Animal Cancer Center.57 For microarray analysis of fresh frozen primary OS tumor samples, total RNA was extracted as described previously.57 Briefly, samples were freeze-fractured, homogenized, extracted with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and further cleaned up and purified with RNeasy extraction kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s protocols. Normal bone RNA was also extracted following this same protocol, with the exception of an additional spin of 800 × g at 4 °C for 5 minutes following homogenization. RNA quantity and quality were preliminarily assessed via Nanodrop spectrophotometer. Quality samples were then shipped to the Genomics and Microarray Core at the University of Colorado where they were bioanalyzed for integrity using an Agilent TapeStation and only those samples having an RNA integrity number of at least 8 were used for microarray analysis.

Pathway (Gene Set Enrichment) Analysis

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/downloads.jsp) was performed according to the user guide (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/doc/GSEAUserGuideFrame.html) to determine biological pathways differentially enriched between periostin “high” and “low” expressing canine primary OS tumors. GSEA is a statistical tool developed for analyzing microarray or other biological expression data based on applying a metric for ranking all genes in an expression dataset and then determining the degree to which gene sets in specific molecularly defined gene signatures are overrepresented at the top (positive enrichment score) or bottom (negative enrichment score) of the ranked list of genes.73 These gene sets are publicly available and housed in the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB; https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp) maintained by the Broad Institute and UC San Diego. The following parameters were used for GSEA analysis: Pathway enrichment between periostin “high” and “low” tumors was done using the Hallmarks gene set (h.all.v6.2.symbols.gmt), with Signal2Noise ranking metric, permutation type set to “gene set,” and 1000 permutations used to calculate statistical significance of enrichment scores. Statistically significant pathways were defined as those with P < .05 and false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted q < 0.05.

Immune Cell Type–Specific Gene Signatures

The relative abundance of immune cell types was determined using a previously described gene expression signature.63 Heatmaps were generated with z-transformed expression values using R software (v3.3) with the “ComplexHeatmap” package.27 For each immune cell type relative “scores” were determined for each sample. A sample’s score for a given immune cell type was calculated as the average of z-transformed expression values of the markers for that cell type. Differentially expressed markers between high versus low periostin-expressing tumors were determined by performing multiple unpaired t tests in Prism (v8) with Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli’s correction for multiple comparisons.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous data were expressed as means ± standard deviation and normality tested using the D’Agostino and Pearson method. For comparison of means between 2 groups with normally distributed data a 2-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test was used, while nonparametric data were compared by a Mann-Whitney U test. Correlation analyses were doing using the Spearman rank test or Pearson analysis, based on normality testing. Canine OS tumor samples were divided into “high” and “low” periostin expressing cohorts based on dichotomization of median log2 mRNA expression of periostin. Disease-free interval (DFI) was calculated from the date of surgical removal of the primary tumor (amputation) to the date of progressive disease, as determined by thoracic radiography and/or clinical examination. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test used for determination of significance in survival outcome between categorical (periostin “high” and “low”) subpopulations, with significance set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism commercial software.

Results

Study Population

Dogs (n = 49) for which primary appendicular OS tumors samples were analyzed for periostin mRNA expression included 21 spayed females, 24 castrated males, 3 intact males, and 1 intact females, with a mean (± SD) age of 8.3 ± 2.2 years, and a range of 4.2 to 13.4 years. All dogs received standard-of-care treatment consisting of surgical removal of their primary tumor followed by adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of either single-agent doxorubicin (n = 13), single-agent carboplatin (n = 13), single-agent cisplatin (n = 5), polymer-based cisplatin (Atriplat, n = 1), doxorubicin-carboplatin combination therapy (n = 16), or doxorubicin-cisplatin-carboplatin combination therapy (n = 1). The median disease-free interval for all dogs was 190 days (range 20–987 days).

Dogs (n = 8) from which normal bone was obtained for expression profiling included 4 castrated males and 4 spayed females, with a mean (± SD) age of 9.3 ± 2.1 years and range of 6.5 to 13.3 years. Breeds included Labrador Retriever (n = 4), Coonhound (n = 1), and mixed breed (n = 3).

Periostin Expression Is Elevated in Canine Osteosarcoma Cell Lines and Tumors

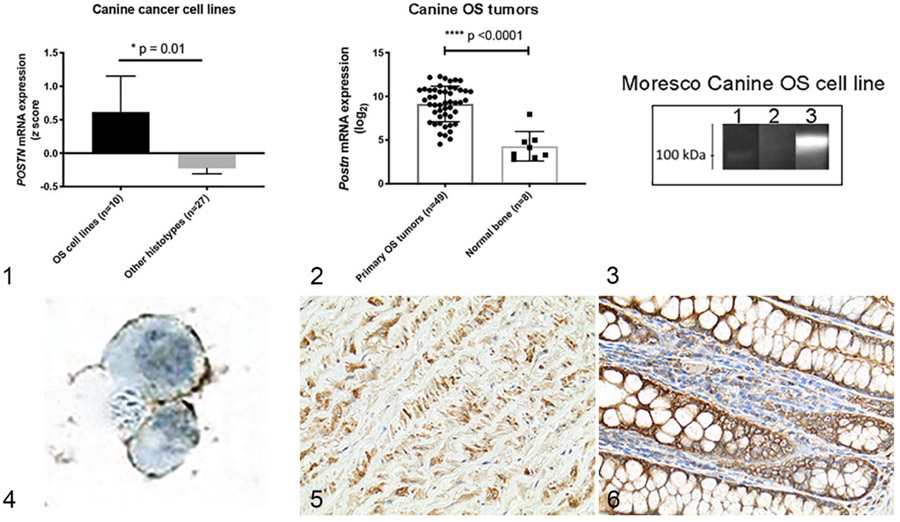

To first investigate a potential role for periostin overexpression in canine OS, we evaluated periostin mRNA expression across a panel of 37 canine tumor cell lines encompassing the following histo-types: osteosarcoma (n = 10), transitional cell carcinoma (n =5), melanoma (n =5), hemangiosarcoma (n =4), leukemia/lymphoma (n =4), mast cell tumor (n =2), histiocytic sarcoma (n =2), soft tissue sarcoma (n =1), mammary carcinoma (n =1), and thyroid carcinoma (n =1). Comparison of z-transformed log2 mRNA expression values of periostin across all canine tumor cell lines demonstrated preferential and significant overexpression of periostin in canine OS tumor cells as compared to all other histo-types (Fig. 1; P = .01, 2-tailed nonparametric Mann-Whitney t test).

Figures 1–6.

z-Transformed periostin (POSTN) mRNA expression values in canine osteosarcoma (OS) cell lines (n = 10) as compared to 27 other canine tumor cell lines encompassing a variety of histo-types. Figure 2. Log2 POSTN mRNA expression in canine primary appendicular OS tumors (n = 49) as compared to normal metaphyseal bone samples (n = 8). Data in Figures 1 and 2 represent mean ± SD, *P < .05 and P < .0001 (unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t-test). Figure 3. Western blot demonstrating antibody detection of a secreted protein of ~ 100 kDa, near the predicted molecular weight (93 kDa) of periostin, in supernatant (lane 3) obtained from the canine Moresco OS tumor cell line. Lane 1 contains protein molecular weight standards and demonstrates the 100 kDa molecular weight marker. Lane 2 consists of Moresco cell line lysate. Figure 4. Immunocytochemistry using this antibody also demonstrated membranous expression of periostin in canine Moresco OS cells. Figures 5 and 6. Immunohistochemical localization of periostin expression in canine formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded positive control (normal) tissues including the tunica media of the aorta (Fig. 5) and colonic mucosa (Fig. 6).

Next, to determine whether these canine cancer cell lines were representative of in vivo periostin expression in OS tumors, we compared periostin mRNA expression between primary appendicular OS tumors (n = 49) and normal metaphyseal bone samples (n = 8). Mean periostin mRNA (log2) expression was elevated 28-fold in primary OS tumors as compared to normal bone (Fig. 2; P < .0001, 2-tailed Student’s t test).

Immunohistochemical Expression of Periostin in Canine Osteosarcoma

Based on this mRNA expression data, we sought to characterize periostin protein expression and localization in canine OS tumors. To do this, we first validated an anti-human periostin antibody reported by the manufacturer to be reactive to canine periostin. Western bot analysis of the Moresco OS cell line (the cell line with the second highest periostin mRNA expression value) performed with this antibody detected a band of ~ 100 kDa, near the predicted molecular weight (~93 kDa) of canine periostin, in Moresco cell culture supernatant (Fig. 3, lane 3). The observance of periostin in cell culture supernatant is expected given the presence of a signal peptide in its amino acid sequence76 and is consistent with the secreted nature of this matricellular protein.31,76 Supporting the results of the western blot analysis, immunocytochemistry for periostin performed with this antibody on the Moresco cell line demonstrated strong membranous localization of periostin (Fig. 4). This membranous localization may be reflective of autocrine binding of secreted periostin to its cognate αvβ3/5 receptors,25,69 which we have observed to be overexpressed in these canine OS cell lines (unpublished data, Regan laboratory).

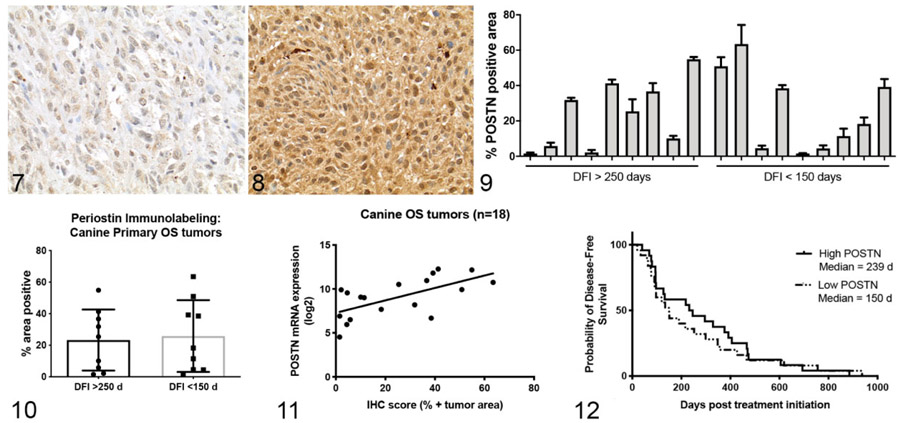

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) performed with this antibody on FFPE canine aorta and colon (positive control tissues) demonstrated strong immunoreactivity and expected localization of periostin expression within myocytes and the extracellular space of the aortic tunica media as well as pericryptal immune and stromal cells and mucosal epithelial cells of the colon (Figs. 5, 6; Supplemental Figures S1, S2)41,82 (and https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000133110-POSTN/tissue). Next, we performed immunohistochemistry for periostin expression on a subset of 18 of the 49 primary OS tumors evaluated for mRNA expression. These 18 cases were chosen based on FFPE block availability as well as equal representation of significant differences in clinical outcome based on disease-free interval (DFI) >250 days (good responders, n = 9) and DFI <150 (poor responders, n = 9). All evaluated tumors (18/18) demonstrated positive immunoreactivity for periostin (Figs. 7, 8). Quantitative image analysis of periostin immunoreactivity (using Image J software as described in Materials and Methods) demonstrated highly variable mean percent positive immunoreactivity across these 18 samples (Fig. 9), with a range of 1.5% to 63.5% of the total tumor area positive for periostin. This variable protein expression was consistent with the wide range of mRNA expression values observed in these tumors. Immunolabeling for periostin within canine OS tumors was characterized by variable weak to strong immunoreactivity localized both within the cytoplasm of neoplastic cells and in the extracellular space (Figs. 7, 8). Overall, these data demonstrate significant overexpression of periostin in canine OS and validate a canine cross-reactive anti-periostin antibody.

Figures 7–12.

Figures 7 and 8. Osteosarcoma (OS), bone, dog. Representative images demonstrating the variability in positive immunolabeling for periostin in the cytoplasm of neoplastic OS cells from case 346 (Fig. 7) and case 999 (Fig. 8). Figure 9. Quantitative image analysis of positive periostin (POSTN) immunolabeling, expressed as percentage of total tumor area, in 18 OS primary tumors from dogs with a disease-free interval (DFI) <150 days or >250 days. Figure 10. Periostin-positive immunolabeling in dogs with DFI <150 days or >250 days. Mean ± SD. Figure 11. Association between periostin mRNA and protein expression (% positive tumor area) for the same subset of tumors shown in Figure 9. Spearman correlation, r = 0.71, P = .001. Figure 12. Kaplan-Meir survival curve demonstrating the relationship between “low” and “high” periostin mRNA expression in OS primary tumors and disease-free intervals in 49 dogs (log rank P = .59).

Association of Periostin Protein and mRNA Expression With Clinical Outcome in Canine Osteosarcoma

Data from the quantitative analysis of periostin immunolabeling was then used to determine whether periostin protein expression was different between those subsets of dogs with favorable clinical outcome (DFI > 250 days) versus those dogs with poor clinical outcome (DFI < 150 days). Immunohistochemical expression of periostin was not significantly different between those dogs with DFI <150 days (mean % periostin positive = 25.8) or >250 days (mean % periostin positive = 23.3; Fig. 10). Similarly, periostin protein expression was not correlated to DFI (r = −0.1, P = .70; data not shown) and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing those dogs with periostin-IHC “high” versus periostin-IHC “low” tumors (based on median dichotomization of the mean percent periostin positive data shown in Fig. 9) was also not significantly different (log rank P = .66; data not shown).

Given the low power and limitations associated with performing survival analysis in only 18 dogs, we sought to determine whether periostin mRNA expression was correlated with disease-free interval in our larger 49 dog subset. This approach was validated by the strong positive linear correlation we observed between periostin mRNA and protein expression in our initial 18 dog cohort (Fig. 11, Spearman r =0.71, P = .001). For Kaplan-Meier analysis, dogs were again divided into periostin mRNA “high” and “low” expressing groups based on median dichotomization. Consistent with our survival analysis results based on periostin IHC expression, no significant difference in disease-free interval was observed between “periostin-High” versus “periostin-Low” expressing tumors (Fig. 12, log rank P = .59). Overall, these data demonstrate that while periostin mRNA and protein expression are variable across dogs with OS, overexpression of this protein was not associated with worse clinical outcome.

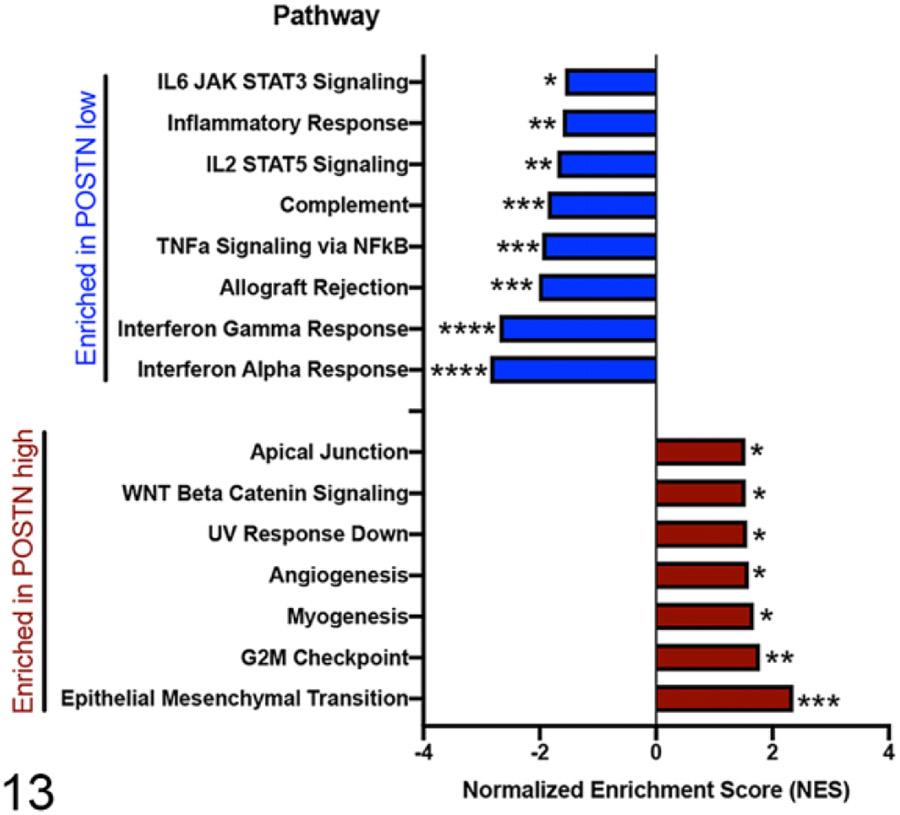

Periostin Overexpressing Osteosarcoma Tumors Are Enriched for Gene Pathways Associated With Hallmarks of Cancer Progression

Despite a lack of association between periostin expression and clinical outcome, we still sought to better understand the functional impact of periostin expression in canine OS, given the wide range in expression values across our cohort of tumors. To do this, we performed pathway analysis with the gene microarray expression data from the 49 canine primary OS tumors using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) software (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp). GSEA analysis evaluates changes in genes between 2 user-defined phenotypes, in this case “periostin mRNA-High” and “periostin mRNA-Low,” using a ranking metric for each gene in order to more globally evaluate gene expression changes and detect differential enrichment in gene sets associated with specific biological processes between these phenotypes.51,73

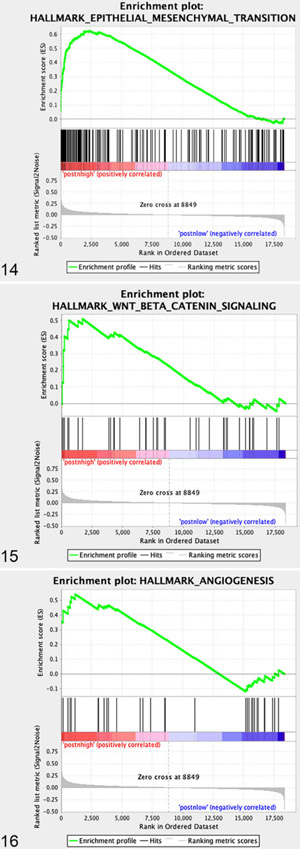

GSEA analysis using the hallmarks gene sets44 comparing “periostin-High” versus “periostin-Low” tumors (again based on median dichotomization) identified statistically significant enrichment (P < .05 and false discovery rate [adjusted P value] q < 0.05) of 7 pathways in “periostin-High” tumors, including “Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition” (EMT), “G2M checkpoint,” “Myogenesis,” “Angiogenesis,” “UV response down,” “WNT Beta Catenin Signaling,” and “Apical Junction” (Fig. 13 and Figs. 14-16). Importantly, the upregulation of these specific pathways in periostin-High OS tumors are consistent with both: (1) previously reported tumor-promoting functions for periostin in human and rodent cancer models, including promotion of EMT,53,59 enhancement of Wnt signaling for cancer stem cell maintenance,45 direct promotion of tumor cell proliferation,1,69,84 and promotion of tumor angiogenesis1,32,59,69,74,85 and (2) periostin’s normal physiologic role as a matricellular protein and cell-interacting component of the extracellular matrix (“Apical Junction”).25,31 These data suggest that periostin may have a similar role in canine tumorigenesis to that observed in other species.

Figure 13.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; Hallmark gene sets of Molecular Signatures Database) of differentially enriched pathways in canine osteosarcoma primary tumors with high (n = 24) versus low (n = 25) periostin mRNA expression. Hallmark gene sets ranked according to normalized enrichment score (NES) and false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted q value, *q < 0.05, **q < 0.01, ***q < 0.001, and ****q < 0.0001.

Figures 14–16.

GSEA enrichment plots of specific gene sets upregulated in periostin “high” versus periostin “low” canine OS primary tumors.

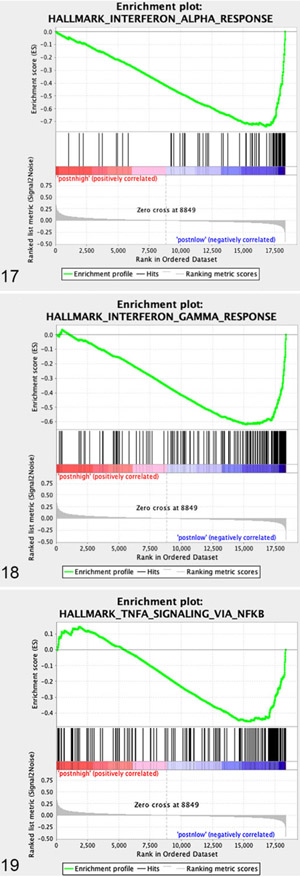

“Periostin-Low” Osteosarcoma Tumors Are Associated With Heightened Immune Activity

GSEA analysis of “periostin-low” expressing tumors demonstrated statistically significant enrichment in 8 pathways (Fig. 13 and Figs. 17-19, P < .05, FDR q < 0.05). Interestingly, all 8 of these gene sets involved immune response processes and included upregulation of genes associated with “Interferon Alpha Response,” “Interferon Gamma Response,” “Allograft Rejection,” “TNFa Signaling via NFkB,” “Complement,” “IL2 STAT5 signaling,” “Inflammatory Response,” and “IL6 JAK STAT3 Signaling,” suggesting heightened immune activity in those canine OS tumors with low periostin expression. To further investigate this association between periostin expression and immune activity, we utilized the microarray expression data for all 49 dogs in our subset in order to compare the immune transcriptome in “periostin-High” versus “periostin-Low” tumors. Previous studies in human cancers have developed the bioinformatic tools necessary for utilization of transcriptomic data to computationally characterize the cellular composition, level, and functional orientation of immune infiltrates in human tumors.3,9,63 These computational strategies for investigating the tumor immune landscape provide certain benefits over antibody-based assays, namely: (1) the ability to leverage previously generated and/or publicly available data sets without the need for tissue blocks and (2) a more detailed investigation of specific immune cell types and their functional orientation which is typically not possible in multiplexed IHC-based applications, especially in nontraditional species for which species-specific or cross-reactive antibodies are limited.

Figures 17–19.

GSEA enrichment plots of specific gene sets upregulated in periostin “low” versus periostin “high” canine OS primary tumors.

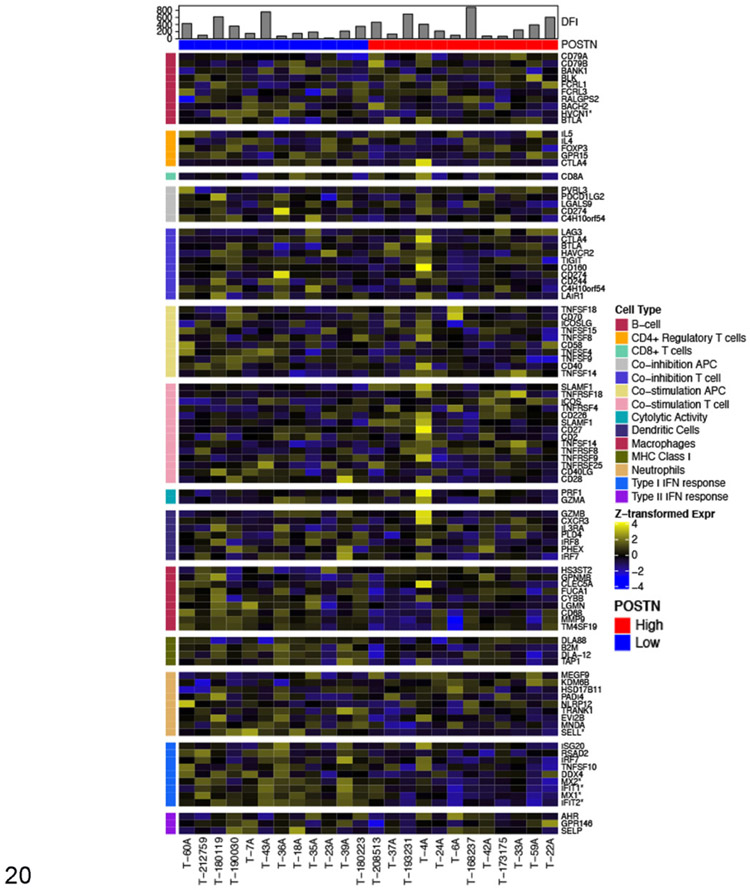

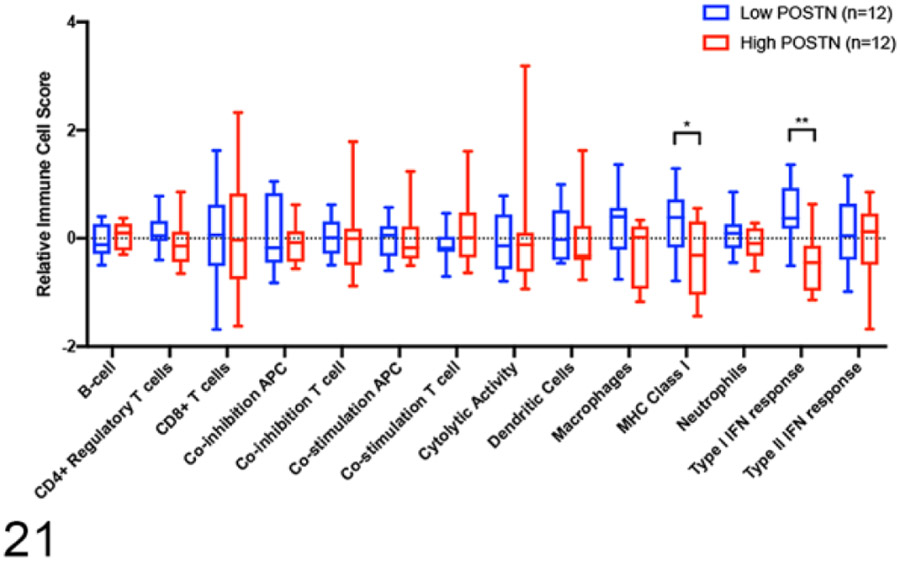

For our study, we utilized previously published cell-type specific gene signatures63 to transcriptomically compare the immune infiltrate between those tumors in the lower quartile (lowest 25%) of periostin expression (POSTN low—blue, n = 12) versus those tumors in the upper quartile (highest 25%) of periostin expression (POSTN high—red, n = 12). Figure 20 is a heat map showing differences in z-transformed expression values for these immune cell signatures between periostin high versus low tumors. The mean z-transformed expression value for all genes comprising each individual immune response signature were then collapsed into a single mean z-score expression value for that specific immune signature, which were then used to statistically compare for differential enrichment of specific immune cell types between “periostin-Low” versus “periostin-High” tumors. In line with the results of our GSEA analysis, “periostin low” tumors had statistically significant enrichment in “Type I Interferon Response” genes and “MHC Class I” antigen presentation genes (Fig. 21, P < .05 and q < 0.05, multiple unpaired t tests with Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli’s correction for multiple comparisons). Although no statistically significant differences in specific immune cell subset expression scores were observed between periostin low versus high tumors, “periostin low” tumors had increases in the mean immune cell signatures for neutrophils (P = .007, q = 0.054), macrophages (P = .02, q = 0.12), dendritic cells, and CD4+ regulatory T cells (Fig. 21). Together, these results provide evidence that canine OS tumors with low expression of periostin have heightened immune infiltrates and may be considered more immunologically “hot” as compared to periostin-high expressing OS.

Figure 20.

Relative expression of immune cell lineage markers in high (n = 12) and low (n = 12) periostin-expressing tumors. Heatmap colors represent z-transformed expression values. Color bars on the top and side specify the periostin expression and immune cell type, respectively. Disease-free intervals (DFI) are represented in the histogram. Asterisks denote markers differentially expressed between high versus low periostin-expressing tumors (FDR q < 0.05 and fold-change of at least 1.5).

Figure 21.

Immune cell scores between high and low periostin-expressing samples. Statistical significance was determined using multiple unpaired t tests with Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli’s correction for multiple comparisons (q < 0.05).

Discussion

Based on periostin’s originally described role in the proliferation and survival of osteoblasts,86 as well as an increasing body of literature describing its pro-tumorigenic function in human cancers through enhancement of tumor cell migration, metastasis, and angiogenesis,1,2,32,33,45,49,69 we sought to investigate whether periostin overexpression was associated with worse clinical outcome in canine OS. Our studies validated an anti-human periostin antibody cross-reactive to canine periostin via western blot, immunocytochemistry, and immunohistochemistry. While periostin mRNA or protein expression alone were not associated with clinical outcome in our subset of 49 dogs with OS, we demonstrate statistically significant differential pathway enrichment between periostin high versus low expressing OS tumors. These pathways strongly overlapped with those tumor-promoting functions reported with periostin overexpression in human cancers, and also suggested that variation in periostin expression levels may be associated with differences in the composition of the canine OS immune landscape.

Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated periostin immunoreactivity in 18/18 canine OS primary tumors evaluated. In these cases, localization of periostin expression was predominately in the cytoplasm of neoplastic cells and extracellular matrix immediately surrounding tumor cells, suggesting that neoplastic OS cells, and not stromal cells such as cancer-associated fibroblasts, are the primary source of periostin expression in these tumors. These observations are further supported by the significant elevation of periostin mRNA expression we demonstrated in our canine OS tumor cell lines. While the degree of periostin mRNA and protein expression varied widely on a case-to-case basis in our cohort, the significant preferential overexpression in canine OS tumor cell lines and OS primary tumors as compared to other tumor histo-types and normal bone, respectively, suggests an important role for this protein in canine OS progression. Importantly, this overexpression demonstrates another similarity between canine and human OS,32,33,76 and provides a foundation and rationale for future studies aimed at investigating periostin and its associated signal transduction pathways in the development of new treatments for OS.

Despite our demonstration of significant and preferential elevation of periostin in canine OS, our study did not demonstrate an association between periostin mRNA or protein expression and disease-free interval in this cohort of 49 dogs. This is in contrast to observations in human cancers, where periostin expression is associated with clinical outcome in OS, ovarian, colon, and glioma.2,32,33,49,75,85 A general limitation of our study, which could account for this lack of association with survival, is our small sample size. For example, one study demonstrating significant association of periostin expression with clinical outcome in glioma patients was performed on gene expression data from subsets ranging in size from 77 to 674 patients.49 Furthermore, these investigators used the statistical power of these large datasets to define a multi-gene “periostin expression signature,”49 something which we were unable to do, and another limitation of our current study. It is likely that incorporation of multiple genes co-regulated with periostin expression may better identify those tumors which are truly dependent on the pro-tumorigenic functions of periostin, leading to better prognostic utility.

Although worse clinical outcome was not associated with elevated periostin levels in canine OS, we provide evidence that specific gene programs and molecular pathways significantly differ between “high” and “low” expressing periostin tumors. In our pathway analysis of periostin overexpressing OS tumors, we observed epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to be the most significantly enriched pathway in these tumors. This enrichment in EMT may seem like a paradox considering OS is already a mesenchymal-derived tumor; however, recent reports have demonstrated other sarcomas to have enrichment for an EMT program.11,17,20,59,66 As primarily demonstrated in epithelial-derived tumors, EMT is related to multiple tumor-promoting functions including increased invasion, motility, metastasis, and drug resistance, and enhanced expression of EMT signatures have been previously associated with patient tumor stage and prognosis.53,66,71 However, these early reports on EMT in sarcomas also suggest similar increased biological aggressiveness associated with this phenotype. Importantly, transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), which plays a key role in initiating EMT transcriptional programs, is one of the principal molecules known to induce periostin secretion and is a potent immune suppressive molecule.45,61,62,81

GSEA analysis also demonstrated significant enrichment of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in those canine OS tumors with high periostin expression, consistent with previously reported associations between this pathway, periostin, and osteosarcoma. Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been demonstrated to promote pro-tumorigenic effects in human OS cells and tumor tissues, and is correlated with metastasis, decreased DFI, and enhanced EMT in OS.10,28-30,65 In breast cancer, periostin is known to generate a tumor-supportive lung metastatic niche via promotion of Wnt ligand accumulation and enhancement of Wnt signaling.4,45 Our data are consistent with prior reports demonstrating enhanced Wnt signaling in canine OS,68 but provide new evidence to suggest this enhancement may be mediated indirectly through periostin overexpression by OS cells. Together, these data provide additional rationale supporting continued investigation into Wnt/β-catenin pathway inhibitors in both canine and human OS, and suggest these therapeutic studies may be best focused on those OS tumors with periostin overexpression.20,65

Interestingly, our pathway analysis of “low periostin” expressing tumors demonstrated significant enrichment in 8 gene sets, of which all are associated with genes upregulated in immune responses. Gene targets upregulated in response to interferon-α (IFN-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were the 2 most significantly enriched pathways in our “periostin-low” tumor subset. IFN-α and IFN-γ are both critical mediators of antitumor immunity, with well-defined requirements for both molecules in effective tumor immune surveillance and response to immune-based therapies such as vaccines, oncolytic agents, and checkpoint inhibitors.23,28,38,88 These data suggest that periostin expression may dictate fundamental differences in the immune landscape of canine OS tumors, which in part is supported by our gene signature-based immune cell profiling performed on these tumors. The association of periostin overexpression with those OS tumors which appear more immunologically “cold” may indirectly reflect enrichment of TGF-β in the tumor microenvironment, given the dependency for this immune suppressive molecule in periostin secretion.45,81 While both IFN-α and IFN-γ have been reported as independent prognostic factors in human cancers,46,54 this association was not observed in our case cohort despite significant upregulation of these pathways. Nonetheless, these data warrant future expanded investigations as to whether the level of enrichment for periostin and/or other ECM protein signatures is associated with response to immune-based therapies in canine OS tumors.

In conclusion, our study validated an anti-human periostin antibody cross-reactive to canine periostin via western blot, immunocytochemistry, and immunohistochemistry. Furthermore, we demonstrate an association between increased periostin expression in canine OS and enhancement of pro-tumorigenic transcriptional programs including canonical Wnt signaling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and angiogenesis. Overall, these data suggest a similar conserved biology for periostin in canine and human carcinogenesis, providing a foundation for future comparative investigations on the role of this protein in tumorigenesis. Furthermore, we identify a novel antibody that can be used as a tool for evaluation of periostin expression in dogs with cancer and other diseases and suggest that investigation of Wnt pathway-targeted drugs in periostin overexpressing canine OS may be a potential therapeutic target.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the oncology service and clinical trials staff at the Flint Animal Cancer Center for procurement of canine osteosarcoma biopsies for gene expression analysis.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by The National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director, Award Number K01ODO22982 (DPR) and R03OD028265 (DPR); Short-Term National Research Award, Award Number T35OD015130 (LNA); and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Award Number L30 TR002126 (DPR). This work was also supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Veterinary Scholar Fellowship (LNA).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Bao S, Ouyang G, Bai X, et al. Periostin potently promotes metastatic growth of colon cancer by augmenting cell survival via the Akt/PKB pathway. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(6):329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben QW, Zhao Z, Ge SF, et al. Circulating levels of periostin may help identify patients with more aggressive colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2009;34(3):821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39(4):782–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnet N, Conway SJ, Ferrari SL. Regulation of beta catenin signaling and parathyroid hormone anabolic effects in bone by the matricellular protein periostin. Proc Nati Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(37):15048–15053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bozyk PD, Bentley JK, Popova AP, et al. Neonatal periostin knockout mice are protected from hyperoxia-induced alveolar simplication. PLoS One. 2012;7(2): e31336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown JM, Mantoku A, Sabokbar A, et al. Periostin expression in neoplastic and non-neoplastic diseases of bone and joint. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2018;8:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruland ØS, Høifødt H, Sæter G, et al. Hematogenous micrometastases in osteosarcoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(13):4666–4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butcher JT, Norris RA, Hoffman S, et al. Periostin promotes atrioventricular mesenchyme matrix invasion and remodeling mediated by integrin signaling through Rho/PI 3-kinase. Dev Biol. 2007;302(1):256–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charoentong P, Finotello F, Angelova M, et al. Pan-cancer immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade. Cell Rep. 2017;18(1):248–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen K, Fallen S, Abaan HÖ, et al. Wnt10b induces chemotaxis of osteosarcoma and correlates with reduced survival. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51(3):349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Guo Y, Yang H, et al. TRIM66 overexpresssion contributes to osteosarcoma carcinogenesis and indicates poor survival outcome. Oncotarget. 2015;6(27):23708–23719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conway SJ, Izuhara K, Kudo Y, et al. The role of periostin in tissue remodeling across health and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(7):1279–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conway SJ, Molkentin JD. Periostin as a heterofunctional regulator of cardiac development and disease. Curr Genomics. 2008;9(8):548–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das S, Idate R, Cronise KE, et al. Identifying candidate druggable targets in canine cancer cell lines using whole-exome sequencing. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18(8):1460–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dernell W, Ehrhart N, Straw R, Vail DM. Tumors of the skeletal system. In: Withrow SJ, Vail DM, eds. Withrow and MacEwen’s Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2007:540–582. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorn CR. The epidemiology of cancer in animals. Calif Med. 1967;107(6):481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwivedi SKD, McMeekin SD, Slaughter K, et al. Role of TGF-β signaling in uterine carcinosarcoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(16):14646–14655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elkins T, Hortsch M, Bieber AJ, et al. Drosophila fasciclin I is a novel homophilic adhesion molecule that along with fasciclin III can mediate cell sorting. J Cell Biol. 1990;110(5):1825–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan TM, Khanna C. Comparative aspects of osteosarcoma pathogenesis in humans and dogs. Vet Sci. 2015;2(3):210–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng ZM, Guo SM. Tim-3 facilitates osteosarcoma proliferation and metastasis through the NF-κB pathway and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fenger JM, London CA, Kisseberth WC. Canine osteosarcoma: a naturally occurring disease to inform pediatric oncology. ILAR J. 2014;55(1):69–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fowles J, Dailey D, Gustafson D, et al. The Flint animal cancer center (FACC) canine tumour cell line panel: a resource for veterinary drug discovery, comparative oncology and translational medicine. Vet Comp Oncol. 2017;15(2):481–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garris CS, Arlauckas SP, Kohler RH, et al. Successful anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapy requires T cell-dendritic cell crosstalk involving the cytokines IFN-γ and IL-12. Immunity. 2018;49(6):1148–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5(10):R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillan L, Matei D, Fishman DA, et al. Periostin secreted by epithelial ovarian carcinoma is a ligand for alphaVbeta3 and alphaVbeta5 integrins and promotes cell motility. Cancer Res. 2002;62(18):5358–5364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.González-González L, Alonso J. Periostin: a matricellular protein with multiple functions in cancer development and progression. Front Oncol. 2018;8:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(18):2847–2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Y, Zi X, Koontz Z, et al. Blocking Wnt/LRP5 signaling by a soluble receptor modulates the epithelial to mesenchymal transition and suppresses met and metalloproteinases in osteosarcoma Saos-2 cells. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(7):964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haydon RC, Deyrup A, Ishikawa A, et al. Cytoplasmic and/or nuclear accumulation of the beta-catenin protein is a frequent event in human osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;102(2):338–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoang BH, Kubo T, Healey JH, et al. Expression of LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) as a novel marker for disease progression in high-grade osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;109(1):106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horiuchi K, Amizuka N, Takeshita S, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel protein, periostin, with restricted expression to periosteum and periodontal ligament and increased expression by transforming growth factor beta. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(7):1239–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu F, Shang XF, Wang W, et al. High-level expression of periostin is significantly correlated with tumour angiogenesis and poor prognosis in osteosarcoma. Int J Exp Pathol. 2016;97(1):86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu F, Wang W, Zhou HC, et al. High expression of periostin is dramatically associated with metastatic potential and poor prognosis of patients with osteosarcoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4(2):249–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaffe N, Robertson R, Ayala A, et al. Comparison of intra-arterial cis-diamminedichloroplatinum II with high-dose methotrexate and citrovorum factor rescue in the treatment of primary osteosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3(8):1101–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia G, Erickson RW, Choy DF, et al. Periostin is a systemic biomarker of eosinophilic airway inflammation in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3):647–654.e610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kager L, Zoubek A, Poütschger U, et al. Primary metastatic osteosarcoma: presentation and outcome of patients treated on neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(10):2011–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaplan DH, Shankaran V, Dighe AS, et al. Demonstration of an interferon gamma-dependent tumor surveillance system in immunocompetent mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(13):7556–7561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khanna C, Fan TM, Gorlick R, et al. Toward a drug development path that targets metastatic progression in osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(16):4200–4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khanna C, Wan X, Bose S, et al. The membrane-cytoskeleton linker ezrin is necessary for osteosarcoma metastasis. Nat Med. 2004;10(2):182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kikuchi Y, Kashima TG, Nishiyama T, et al. Periostin is expressed in pericryptal fibroblasts and cancer-associated fibroblasts in the colon. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56(8):753–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kudo Y, Siriwardena B, Hatano H, et al. Periostin: novel diagnostic and therapeutic target for cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22(10):1167–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurzman ID, MacEwen EG, Rosenthal RC, et al. Adjuvant therapy for osteosarcoma in dogs: results of randomized clinical trials using combined liposome-encapsulated muramyl tripeptide and cisplatin. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1(12): 1595–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1(6):417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malanchi I, Santamaria-Martínez A, Susanto E, et al. Interactions between cancer stem cells and their niche govern metastatic colonization. Nature. 2012;481(7379):85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marth C, Fiegl H, Zeimet AG, et al. Interferon-gamma expression is an independent prognostic factor in ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(5):1598–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masuoka M, Shiraishi H, Ohta S, et al. Periostin promotes chronic allergic inflammation in response to Th2 cytokines. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(7):2590–2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Krailo M, et al. Osteosarcoma: a randomized, prospective trial of the addition of ifosfamide and/or muramyl tripeptide to cisplatin, doxorubicin, and high-dose methotrexate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):2004–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mikheev AM, Mikheeva SA, Trister AD, et al. Periostin is a novel therapeutic target that predicts and regulates glioma malignancy. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(3):372–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer. 2009;115(7):1531–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34(3):267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morello E, Martano M, Buracco P. Biology, diagnosis and treatment of canine appendicular osteosarcoma: similarities and differences with human osteosarcoma. Vet J. 2011;189(3):268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morra L, Moch H. Periostin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: a review and an update. Virchows Arch. 2011;459(5):465–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Müller CR, Smeland S, Bauer HCF, et al. Interferon-alpha as the only adjuvant treatment in high-grade osteosarcoma: long term results of the Karolinska Hospital series. Acta Oncol. 2005;44(5):475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Naik PK, Bozyk PD, Bentley JK, et al. Periostin promotes fibrosis and predicts progression in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303(12):L1046–L1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nie Z, Peng H. Osteosarcoma in patients below 25 years of age: an observational study of incidence, metastasis, treatment and outcomes. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(5):6502–6514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O’Donoghue LE, Ptitsyn AA, Kamstock DA, et al. Expression profiling in canine osteosarcoma: identification of biomarkers and pathways associated with outcome. BMC cancer. 2010;10:506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paoloni M, Davis S, Lana S, et al. Canine tumor cross-species genomics uncovers targets linked to osteosarcoma progression. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park SY, Piao Y, Jeong KJ, et al. Periostin (POSTN) regulates tumor resistance to antiangiogenic therapy in glioma models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15(9):2187–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Priester WA. The Occurrence of Tumors in Domestic Animals. US Department of Health and Human Services; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qi Y, Wang N, He Y, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1 signaling promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like phenomena, cell motility, and cell invasion in synovial sarcoma cells. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ranges GE, Figari IS, Espevik T, et al. Inhibition of cytotoxic T cell development by transforming growth factor beta and reversal by recombinant tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med. 1987;166(4):991–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, et al. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 2015;160(1-2):48–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rowell JL, McCarthy DO, Alvarez CE. Dog models of naturally occurring cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17(7):380–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rubin EM, Guo Y, Tu K, et al. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 decreases tumorigenesis and metastasis in osteosarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(3):731–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sannino G, Marchetto A, Kirchner T, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in mesenchymal tumors: a paradox in sarcomas? Cancer Res. 2017;77(17):4556–4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Selmic L, Burton JH, Thamm D, et al. Comparison of carboplatin and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy protocols in 470 dogs after amputation for treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2014;28(2):554–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Selvarajah GT, Kirpensteijn J, van Wolferen ME, et al. Gene expression profiling of canine osteosarcoma reveals genes associated with short and long survival times. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shao R, Bao S, Bai X, et al. Acquired expression of periostin by human breast cancers promotes tumor angiogenesis through up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(9):3992–4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Snider P, Hinton RB, Moreno-Rodriguez RA, et al. Periostin is required for maturation and extracellular matrix stabilization of noncardiomyocyte lineages of the heart. Circ Res. 2008;102(7):752–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Soltermann A, Tischler V, Arbogast S, et al. Prognostic significance of epithelial-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-epithelial transition protein expression in non–small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(22):7430–7437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Straw R, Powers B, Withrow S, et al. The effect of intramedullary polymethylmethacrylate on healing of intercalary cortical allografts in a canine model. J Orthop Res. 1992;10(3):434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Nati Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun F, Hu Q, Zhu Y, et al. High-level expression of periostin is significantly correlated with tumor angiogenesis in prostate cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11(3):1569–1574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sung PL, Jan YH, Lin SC, et al. Periostin in tumor microenvironment is associated with poor prognosis and platinum resistance in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(4):4036–4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Takeshita S, Kikuno R, Tezuka KI, et al. Osteoblast-specific factor 2: cloning of a putative bone adhesion protein with homology with the insect protein fasciclin I. Biochem J. 1993;294(Pt 1):271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tilman G, Mattiussi M, Brasseur F, et al. Human periostin gene expression in normal tissues, tumors and melanoma: evidences for periostin production by both stromal and melanoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Uchida M, Shiraishi H, Ohta S, et al. Periostin, a matricellular protein, plays a role in the induction of chemokines in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46(5):677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Withrow S, Thrall D, Straw R, et al. Intra-arterial cisplatin with or without radiation in limb-sparing for canine osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1993;71(8):2484–2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Withrow SJ, Wilkins RM. Cross talk from pets to people: translational osteosarcoma treatments. ILAR J. 2010;51(3):208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wojtowicz-Praga S Reversal of tumor-induced immunosuppression by TGF-beta inhibitors. Invest New Drugs. 2003;21(1):21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamashita O, Yoshimura K, Nagasawa A, et al. Periostin links mechanical strain to inflammation in abdominal aortic aneurysm. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yun H, Kim EH, Lee CW. 1H, 13C, and 15N resonance assignments of FAS1-IV domain of human periostin, a component of extracellular matrix proteins. Biomol NMR Assign. 2018;12(1):95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhou W, Ke SQ, Huang Z, et al. Periostin secreted by glioblastoma stem cells recruits M2 tumour-associated macrophages and promotes malignant growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(2):170–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhu M, Fejzo MS, Anderson L, et al. Periostin promotes ovarian cancer angiogenesis and metastasis. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(2):337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhu S, Barbe MF, Liu C, et al. Periostin-like-factor in osteogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218(3):584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zinn K Sequence analysis and neuronal expression of fasciclin I in grasshopper and Drosophila. Cell. 1988;53(4):577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, et al. Type I interferons in anticancer immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(7):405–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.