Abstract

Guided by cognitive appraisal theory, we argue that wish-making is a conceptually distinct type of coping strategy and that wish-making during the COVID-19 pandemic has functional cognitive–affective consequences. Specifically, it facilitates positive appraisals of the pandemic, which then facilitate job satisfaction. Enhanced job satisfaction in turn reduces counterproductive work behavior during the pandemic. These arguments were tested via two empirical studies involving 546 Hong Kong employees surveyed on two consecutive working days during the pandemic. The individuals who made wishes during the pandemic reported more positive appraisals of the pandemic, which in turn promoted their job satisfaction and lowered their counterproductive work behavior. Crucially, wish-making had significant effects on positive appraisals above and beyond other coping strategies. Thus, we contribute to the employee coping literature by highlighting one relatively easy way for employees to combat the psychological effects of the pandemic (and other challenges in life) and regulate their affective well-being and behaviors at work. Namely, making wishes that envision a better future can enhance employees' job satisfaction, which in turn lowers counterproductive work behavior.

Keywords: Wishes, Pandemics, Appraisals, Job satisfaction, Counterproductive work behavior

People make wishes all of the time. On birthdays and New Year's Eve, people wish for the things they desire in life. In the workplace, employees may wish to avoid the next round of layoffs. They may wish for their bosses to be in a good mood, for their customers to sign big sales contracts, or for their organization to give them a private office. During the pandemic, many people might have frequently made wishes; this includes wishing that the pandemic be over soon, that vaccines become swiftly available, and that those they care about stay healthy.

Despite the prevalence of wish-making, research on coping strategies (Bjorck & Cohen, 1993; Bolger, 1990; Folkman & Lazarus, 1980; McCrae, 1984) has seldom considered its benefits in combating stress. Most taxonomies of coping strategies do not include future-oriented wish-making (Skinner et al., 2003; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007; Tobin et al., 1989), perhaps because very little is known about its nature and effects. Another reason is the assumption that wish-making operates in the same way as other coping strategies. However, wish-making is unique in that it can both alleviate the emotional consequences of a stressor (by directing individuals' attention to a positive future that they wish for) and help motivate the use of problem-focused tactics (by making salient individuals' goals in life). Most coping strategies are either emotion-focused or problem-focused in nature, but not both. At the same time, wish-making is not the same as coping through optimism (Segerstrom et al., 1998) and constructive thinking (Epstein & Meier, 1989). Whereas thinking optimistically or constructively about the future generally helps a person cope with stress, wish-making especially helps because it directly creates a mental image of a better future and makes salient specific life goals, both of which can potentially sustain the person's coping motivation and efforts in the long run. Wish-making also differs from coping through goal-setting (Körner et al., 2015) in that it can have immediate healing power by making vivid people's ideals and dreams, whereas goal-setting may not yield satisfaction until some progress has been made on those goals.

The omission of wish-making from coping research potentially hinders theory development because it means that the scholarly understanding of the different methods that individuals adopt to combat stress is incomplete. A person may frequently engage in wish-making to handle stress, but researchers may enquire about other coping strategies that are not used by that person. Thus, examining wish-making as a coping strategy has the potential to advance coping research by expanding its theoretical scope to include an overlooked tactic, complementing existing coping frameworks, and stimulating the further identification of other coping strategies. Echoing this call for more theoretical inquiries into wish-making as a coping strategy, Schonbachler, Stojkovic, and Boothe (2016, p. 163) note that “there is a lack of interdisciplinary work regarding the mental processes of wishing” and that “wishing is an effective method of coping with stress when there is no better solution available or when a person needs to be able to wait for a while, until the reality can be changed in a way” (p. 166). It is therefore crucial to theorize the effects of wish-making above and beyond other coping strategies and to introduce this tactic to the behavioral repertoires that individuals use to help them deal with life's challenges (Carver, 1997; Endler & Parker, 1990).

Advancing our knowledge about the effects of wish-making also carries important clinical or mental health benefits. From a practical standpoint, wish-making is convenient and efficient, can be done on a day-to-day basis, and is also often motivated by hardship (Wolman et al., 2001). Wish-making is therefore highly relevant to the context of the pandemic, which has caused many people daily anxiety (Hu et al., 2020; Trougakos et al., 2020; Wanberg et al., 2020). If wish-making can in any way alleviate the negative consequences of the pandemic, people should engage in it more frequently, especially given the ease of doing so. As such, understanding the benefits of wish-making would equip people to better deal with the pandemic. For example, wish-making can create a vision of a better future, which would in turn help people sustain their mental health; this is highly important because the threat of the pandemic (or other global crises) may continue for years to come.

Guided by cognitive appraisal theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), which suggests that how individuals interpret a situation determines their affective well-being, we posit that wish-making can trigger a cognitive–affective internal process that benefits wish-makers by leading them to positively interpret an ongoing situation. Positive appraisals entail attending to the positive aspects of a situation and attaching positive meanings to it (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). Such positive appraisals, in turn, create a mental frame in which individuals attend to positive, rather than negative, aspects of their work, contributing to their heightened job satisfaction. Job satisfaction has been frequently used as a robust indicator of affective well-being in the workplace (Crede et al., 2007; Harrison et al., 2006; Judge et al., 1997; Thoresen et al., 2003).

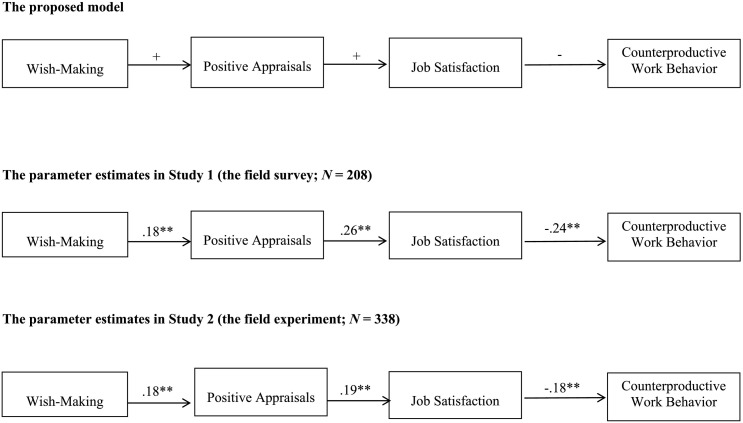

To show that enhanced job satisfaction (as a result of wish-making and positive appraisals) matters, we further relate job satisfaction to counterproductive work behavior, or employee behavior that hurts organizational interests (Bennett & Robinson, 2003). We include counterproductive work behavior (e.g., tardiness, early departure, decreased work effort, and aggressive behavior) as an extended outcome of job satisfaction because the pandemic is currently a prominent stressor in most people's lives, creating both incentives and disincentives for deviance. Counterproductive work behavior may increase due to pandemic-triggered negative emotions (Hu et al., 2020; Trougakos et al., 2020; Wanberg et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021). However, it may decrease due to the mounting threat of job insecurity and layoffs during the pandemic (Ganson et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2021). Thus, it is theoretically worthwhile to explore the different routes by which the pandemic gives rise to, or discourages, counterproductive work behavior. By examining the (negative) indirect effects of wish-making on counterproductive work behavior, we show that wish-making during the pandemic can ultimately decrease one's deviant acts in the workplace, thus uncovering at least one possible way of how coping with the pandemic (through wish-making) can eventually reduce such behaviors. In fact, examining counterproductive work behavior from the perspective of cognitive appraisal theory, the theoretical framework we use here, has been recommended by other researchers (Martinko & Zellars, 1998). Counterproductive work behavior is driven by how people interpret events around them and by their resulting affective reactions (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Extending our investigation of the cognitive–affective internal process instigated by wish-making to examine counterproductive work behavior as a behavioral outcome therefore aligns with our use of cognitive appraisal theory as a theoretical backbone in this research. The proposed theoretical model is summarized in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

The Proposed Model and Parameter Estimates.

1. Theoretical background

1.1. Wish-making as a unique coping strategy

When facing stressors, individuals' coping strategies are arguably the most important factor in determining their mental health outcomes (Rohde et al., 1990; Shin et al., 2014). Coping is the thought or action that people engage in when they are under stress (Carver et al., 1989). As Lazarus and Folkman (1984, p. 141) note, coping represents “the cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person.” Many coping strategies have been identified in the literature (Endler & Parker, 1990; Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Tobin et al., 1989). We discuss some of the most commonly used strategies from the COPE framework (Carver et al., 1989), which is one of the most frequently adopted taxonomies (Kato, 2015).

Problem-focused coping strategies involve fighting the source of stress (Amirkhan, 1990). For instance, active coping entails taking active steps to try to remove a stressor or to reduce its effects. Planning involves laying out a scheme for how to cope with a stressor. Seeking informational support is obtaining advice or relevant information from others to deal with a stressor. Emotion-focused coping strategies involve managing or reducing the emotional consequences of a stressor (Endler & Parker, 1990). Seeking emotional support entails gaining sympathy and understanding from others. Venting entails expressing one's distress outwards. Behavioral disengagement entails reducing one's effort to deal with a stressor. Self-distraction entails mentally disengaging oneself from thinking about a stressor. Denial entails convincing oneself that a stressor does not exist. Acceptance entails accepting the reality of a stressful situation and learning to live with it. Substance use entails resorting to drugs or alcohol to numb one's feelings. Humor entails making fun or light of a stressor. Taken together, these coping tactics help individuals either deal with the problem that causes their distress or regulate their emotions and feelings as a result of experiencing that problem (Folkman et al., 1986).

Wish-making is conceptually distinct from the abovementioned coping strategies. Wish-making is unique because it can be considered an amalgam of both emotion-focused and problem-focused coping strategies. First, wish-making helps direct individuals' attention to a positive state in the future. It takes individuals to a future dreamland where the stressor does not exist. It is important to note that wish-making is not merely wishful thinking (Halstead et al., 1993); wishful thinking entails fantasizing about alternative outcomes that are often impossible to attain in reality (e.g., changing the past; Babad et al., 1992; Krizan & Windschitl, 2009). Wish-making can draw individuals' attention to the authentic possibility of a better future, alleviating the distress created by the stressor. Some of the emotion-focused coping tactics (e.g., self-distraction, denial, substance use, and behavioral disengagement) are helpful in blocking the distress that would otherwise be caused by the current negative reality. However, none of them compels individuals to think about the possibility of a positive reality.

Wish-making can also facilitate the use of problem-focused coping strategies. Wish-making is not just thinking of anything positive. It entails people thinking about the possibility of a better future that they want to attain. Thus, unlike other coping strategies that only deal with the emotional consequences of a stressor but do not remove or reduce the problem (Bolger, 1990; Carver et al., 1993; Stanton & Snider, 1993), wish-making can potentially become the inner engine that fuels people to adapt to the situation and to work toward the better future or other life goals that are made salient through wish-making. Wish-making therefore aids individuals to find the motivation to remove the source of the stress, allowing other problem-focused tactics to be set in motion. For instance, through envisioning a better future in which the pandemic is gone, individuals may find the motivation to take vaccines and adopt other preventative health measures more rigorously. Thus, wish-making not only instills the positivity needed to deal with the emotional consequences of a stressor but also motivates more proactive actions to tackle or remove the stressor by clarifying, and making salient, what individuals want.

Wish-making is also different from seeking emotional and informational support from others in that it does not require help from others. Individuals can make wishes by themselves; they do not require assistance from others in doing so. In some sense, wish-making is a more resource-efficient coping tactic than seeking emotional and informational support. Wish-making is also distinct from venting, acceptance, and humor. These coping strategies involve thoughts and actions that help individuals accept or tolerate the stressor. Wish-making does not necessarily entail acceptance or tolerance. Individuals can still make wishes even if they refuse to live with the stressor or continue to express negative feelings about and mock it. Finally, wish-making is also distinct from active coping and planning. Active coping and planning certainly carry positive implications in that individuals attempt to directly address the causes of the problems. Wish-making also carries positive implications because individuals are making wishes for a positive future. However, wish-making is different from these coping strategies in that it does not necessarily entail the future-oriented actions captured by active coping and planning. Individuals can still make wishes and experience the positive consequences of wish-making even if there are no concrete and/or proactive actions involved. The power of wish-making is that the action of making wishes itself can produce positive and functional influences even when individuals do not immediately engage in any follow-up actions on their wishes, although it is likely that wish-making will make some of the goals and wants salient, as argued above.

1.2. Cognitive appraisal theory

The effects of wish-making on employees' job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior can be explained by cognitive appraisal theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). This theory asserts that a person's affective well-being depends on that person's appraisal of the environment. When an individual interacts with the environment, an external event that the individual encounters may provoke cognitive appraisals, which consist of two connected stages (Smith & Lazarus, 1993). Primary appraisals involve a determination of whether the event is relevant to a person's goals; it is the process of perceiving a threat to oneself. Once this is determined, secondary appraisals involve a determination of whether one can cope with the event. Thus, secondary appraisal is the process of determining a potential response to the threat, including a consideration of coping strategies (Carver et al., 1989). Individuals begin to feel stress when they judge that they do not have sufficient resources to handle the situation, which in turn calls for the use of a coping strategy (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988). Thus, the choice of coping strategies often occurs during the secondary appraisal. As Folkman, Lazarus, Gruen, and DeLongis (1986, p. 572) note, “[i]n secondary appraisal the person evaluates what, if anything, can be done to overcome or prevent harm or to improve the prospects for benefit. Various coping options are evaluated, such as changing the situation, accepting it, seeking more information, or holding back from acting impulsively.” Ultimately, coping allows one to better manage the demands of a particular person-environment transaction that has relevance to the person's well-being (Folkman et al., 1986). However, coping is not the end of a person-environment transaction (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985). The coping process may become the input to feed subsequent episodes of primary and secondary appraisals, determining individuals' long-term affective well-being (e.g., satisfaction and stress). As Folkman and Lazarus (1988, p. 467) note, one's coping process could alter the person-environment relationship and “[t]he altered person-environment relationship is reappraised, and the reappraisal leads to a change in emotion quality and intensity.”

The abovementioned coping-appraisal-emotion sequence is at the core of this study. We argue that wish-making, a coping strategy, can spark the onset of a cognitive–affective sequence that affects employees in the long run. When employees encounter the pandemic, their cognitive appraisals are likely to lead them to consider adopting different coping strategies, including wish-making. Crucially, wish-making helps because it spurs individuals to appraise the pandemic in a more positive light, which should enhance their positive affective well-being. As a result, they are likely to also approach work with a more positive mindset and experience more positive affect at work, as manifested in greater job satisfaction that lowers their counterproductive work behavior. These assertions are explained in greater detail below.

1.3. Wish-making and positive appraisals

Wishes are aims that reflect the desired future (King & Broyles, 1997). “Wish-making” refers to the generation of mental statements, often expressed to oneself internally, that describe one's preferred life (Akhtar, 1999). Wishes can be very specific (e.g., wishing to be held close by someone; Stein & Sanfilipo, 1985) or broad in scope (e.g., wishing for world peace; Leshem, 2017). Whereas future-oriented wishes do not have the potency or urgency to become immediate wants (Heckhausen & Kuhl, 1985), they still represent a desired state of life or reality that underlies people's long-term goals; this captures the notion that individuals often hold the hope, even if it is merely a slim hope, that their wishes will someday come true (Chaves et al., 2016; King & Broyles, 1997; Wittenberg et al., 2017). Wish-making, therefore, is a functional cognitive process that draws people's attention to their dreams, visions, and ideals.

The attention-shifting power of wish-making leads us to propose that when people face hardships and obstacles in their lives, wish-making can facilitate positive appraisals that direct them to focus on the possibility of a better future. The notion of positive appraisals refers to a cognitive process in which positive meanings are attached to a situation; for example, a situation can be viewed as an opportunity to attain personal growth through handling the situation (Carver et al., 1989). Positive appraisals often entail using a perspective that conceives of a situation as positive rather than negative (Kraft et al., 1985; Masters, 1992). We focus on positive appraisals of the pandemic, which is currently a salient experience in most people's lives. Despite our focus on the pandemic, our proposed theory about the effects of wish-making on individuals should apply to other life challenges as well.

When they make wishes during the pandemic, individuals think about the things that they desire (Shoshani et al., 2016). This makes their preferred future more vivid to them than is the case for those who do not make such wishes. A focus on dreams, visions, and ideals is an important self-regulation mechanism because when individuals see the possibility of a better future, they may use a more positive mental frame to process information about the pandemic. Certainly, the pandemic is a negative experience for most people. However, positive appraisals drive individuals to use a less negative mental frame to interpret the experience. Wish-making prevents the mind from thinking solely about the negative aspects of the pandemic and propels individuals to search for positive meanings as well; such positive meaning could include a renewed appreciation of the value of life, increased health-consciousness, the acquisition of new medical knowledge, and the strengthening of bonds with close friends and family. This, in essence, frames the pandemic in a positive way. By making wishes, people clarify to themselves what they value in their lives, and these values comprise their dreams, visions, and ideals. Thus, wish-makers believe that a better future—for example, living happily after the pandemic—is in sight. Schonbachler et al. (2016) similarly emphasize that wish-making can create optimistic thoughts, help individuals find pleasure, and activate the reward-seeking cognitive system. King and Broyles (1997, p. 56) also emphasize that “wishing involves desired future states and to some extent wishing is itself an act of optimism.” The attention-shifting power of wish-making directs people to consider the positive aspects of the pandemic and facilitates a positive interpretation of the pandemic. As we note above, wish-making is distinct from other coping strategies. Its effects on positive appraisals should therefore be evident even after other coping strategies are controlled for.

Hypothesis 1

Wish-making is positively related to positive appraisals, even after controlling for the effects of other coping strategies.

1.4. Positive appraisals and job satisfaction

A major premise of cognitive appraisal theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) is that individuals' affective well-being depends on how they interpret the external environment. As Lazarus (1982, p. 1019) notes, a person's affective reaction is invoked “by a complex cognitive appraisal of the significance of events for one's well-being.” When individuals appraise the external environment in a more positive light, they are more likely to experience positive affective well-being internally (Cheshire et al., 2010; Kraft et al., 1985; Moore et al., 2010; Samios & Baran, 2018; Stoeber & Janssen, 2011). Neurocognitive evidence indicates that during positive appraisals, the part of the brain that is responsible for negative emotions is deactivated and the part responsible for positive emotions is activated (Van Reekum et al., 2009). Based on the cognitive–affective mechanism advocated by cognitive appraisal theory, we argue that individuals who engage in more positive appraisals of the pandemic should experience greater job satisfaction, which is the pleasurable emotional state resulting from a positive appraisal of one's job (Locke, 1969).

Job satisfaction is often a post-cognitive response to the mental processing of positive information (James & Tetrick, 1986). Those who engage in positive appraisals of the pandemic may experience greater job satisfaction because they also use a positive mental frame to process work information. That is, individuals' positive mindsets (as a result of positive appraisals of the pandemic) may direct their attention to the positive aspects of their work environment. In fact, positive appraisals may involve cognitive restructuring that gives precedence to positive rather than negative information in other situations (Neeleman, 1992). This “positivity carryover” argument is consistent with the observation that a positive mental frame, once adopted, can stick in the mind and continue to exert influence in other contexts (Ledgerwood & Boydstun, 2014). As Sparks and Legerwood (2017, p. 1086) note, “[p]eople do not always just respond based on the current frame in the current context, … their judgments are also influenced by the frames they have seen before.” Similarly, positive appraisals of the pandemic may fix individuals' focus on positive information, and this self-regulated attentiveness to positive information can be carried over to the work domain. Consequently, they may experience greater job satisfaction due to their mental focus on the positive aspects of the workplace (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). For instance, they may downplay negative work information, selectively attend to positive work information, process that information more strongly, remember that information longer, and retrieve that information more easily. This may then cause them to experience stronger job satisfaction than people who do not engage in positive appraisals of the pandemic.

Hypothesis 2

Positive appraisals are positively related to job satisfaction.

1.5. Job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior

Job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior are closely and negatively related; those with greater job satisfaction are less likely to engage in counterproductive work behavior. One of the most immediate antecedents of counterproductive work behavior is a person's feelings about their job (Lee & Allen, 2002). Job satisfaction succinctly captures these affective feelings (Locke, 1969). Judge et al. (2006) argue that if counterproductive work behavior is a form of adaptation and adjustment, then dissatisfied employees engage in counterproductive work behavior to regulate their negative feelings about their job. Similarly, Mount et al. (2006) contend that as a summary evaluation of an employee's reaction to work, job satisfaction should closely determine whether the employee will be counterproductive. In a meta-analysis, Dalal (2005) also observes that job satisfaction is one of the strongest antecedents of counterproductive work behavior. Thus, positive appraisals (as a result of wish-making) do not merely relate to affective feelings like job satisfaction but also relate, at least indirectly through those affective feelings, to counterproductive work behavior.

Hypothesis 3

Job satisfaction is negatively related to counterproductive work behavior.

1.6. Mediating effects

The preceding argument suggests that positive appraisals and job satisfaction sequentially mediate the link between wish-making and counterproductive work behavior. This sequential mediating effect is grounded in cognitive appraisal theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984); the appraisal of a situation determines one's affective well-being. When wish-making propels individuals to engage in positive appraisals of the pandemic, they are unlikely to apply a solely negative mental frame to the work domain. Instead, they apply a positive mental frame to the work domain. This mental focus on the positive aspects of work results in positive affective well-being at work (i.e., job satisfaction), which in turn decreases counterproductive work behavior.

Hypothesis 4

Positive appraisals and job satisfaction sequentially mediate the relationship between wish-making and counterproductive work behavior.

2. Study 1: the field study

2.1. Samples and procedures

Various forms of convenience sampling have been adopted in field studies, such as using student contacts with employed individuals (Halbesleben & Bowler, 2007; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006; Priesemuth et al., 2014; Tepper, 1995), asking working students to participate directly or to refer other working adults to join (Grant & Mayer, 2009; Piccolo et al., 2010), using the authors' social contacts to create a sample (Butts et al., 2015; Panaccio & Vandenberghe, 2012), or a combination of the above tactics (Hulsheger, 2016; McGrath et al., 2017; Wang & Groth, 2014).

Our sampling approach aligned with the aforementioned techniques. We sent invitations to our personal and professional contacts in Hong Kong and offered a small monetary incentive (approximately US$10) in exchange for their participation. Although not as serious as in the United States, the pandemic situation in Hong Kong remains alarming, with waves of confirmed cases continuing to hit the city. Hong Kong was thus a suitable site for this study. Interested individuals were also encouraged to recommend their employed contacts to participate. A total of 238 individuals agreed to participate, and 208 subsequently responded to both daily surveys. The mean age of the respondents was 31 years old, 62% were female, 37% were married, 98% had a college education, and 50% had worked for their current employer for 1–5 years. We sent the day 1 survey to the participants on the morning of a working day. On the morning of the next working day, we sent the participants the day 2 survey.

2.2. Measures

Table 1 shows the correlations among the study variables. We used 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) as the item response anchors. Wish-making was measured in the day 1 survey. We first described the context for the respondents as follows: “In fighting the on-going COVID-19 pandemic, how often do you make wishes? For instance, some people have expressed the following wishes: ‘I wish the pandemic will go away soon,’ ‘I wish the vaccines will be available next month,’ and ‘I wish my family will have good health forever.’ What about you? Do you make wishes during the pandemic?” Next, we asked the respondents to rate the degree to which they had been making future-oriented wishes to deal with the pandemic, using the following five items, which we specifically created for the current study (α = 0.89): (1) “I make wishes to deal with the challenge,” (2) “I cope with the hardship through making wishes,” (3) “I develop the habit of making wishes to handle the stress,” (4) “I keep making wishes to overcome the distress,” and (5) “I make wishes to manage the situation.”

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables in study 1 (the field survey).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Wish-making | (0.89) | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Positive appraisals | 0.24⁎⁎ | (0.89) | ||||||||||||||

| 3 Job satisfaction | 0.10 | 0.27⁎⁎ | (0.88) | |||||||||||||

| 4. Counterproductive work behavior | 0.04 | -0.01 | -0.22⁎⁎ | – | ||||||||||||

| 5. Religiousness | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.05 | (0.89) | |||||||||||

| 6. Self-distraction | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.10 | -0.01 | -0.07 | (0.63) | ||||||||||

| 7. Substance use | 0.17⁎ | -0.02 | -0.03 | 0.20⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.12 | (0.90) | |||||||||

| 8. Behavioral disengagement | 0.16⁎ | -0.10 | -0.02 | 0.18⁎ | 0.01 | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.31⁎⁎ | (0.71) | ||||||||

| 9. Denial | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.09 | -0.02 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.40⁎⁎ | 0.54⁎⁎ | (0.75) | |||||||

| 10. Venting | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.12 | -0.03 | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.09 | 0.39⁎⁎ | 0.20⁎⁎ | 0.30⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | (0.31) | ||||||

| 11. Acceptance | 0.14⁎ | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.02 | 0.04 | -0.07 | 0.27⁎⁎ | -0.18⁎⁎ | -0.21⁎⁎ | -0.28⁎⁎ | 0.15⁎ | (0.69) | |||||

| 12. Humor | 0.08 | 0.16⁎ | 0.11 | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.13 | -0.04 | -0.01 | 0.17⁎ | 0.15⁎ | (0.81) | ||||

| 13. Emotional support | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.44⁎⁎ | 0.08 | 0.07 | (0.62) | |||

| 14. Informational support | 0.27⁎⁎ | 0.07 | -0.07 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.50⁎⁎ | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.70⁎⁎ | (0.71) | ||

| 15. Active coping | 0.04 | 0.24⁎⁎ | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.43⁎⁎ | -0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | (0.51) | |

| 16. Planning | 0.01 | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.14⁎ | 0.38⁎ | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.16⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.05 | 0.28⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | (0.49) |

| Mean | 2.86 | 3.50 | 3.06 | 2.88 | 2.23 | 3.31 | 1.65 | 2.51 | 2.24 | 3.12 | 3.79 | 2.89 | 3.20 | 3.28 | 3.55 | 3.38 |

| SD | 0.82 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 2.68 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.64 |

Note. N = 208.

p < .01.

p < .05.

The level of positive appraisals was also measured in the day 1 survey. It was measured using nine items (α = 0.89) adapted from existing scales (Aalto et al., 2002; Carver, 1997; Evers et al., 2001; Garnefski & Spinhoven, 2001; Stein et al., 2016). An example item is, “I believe that I can learn something meaningful from the pandemic.”

Job satisfaction and counterproductive work behaviors were measured in the day 2 survey. Job satisfaction was measured using six items (α = 0.88) used by Iverson et al. (1998). An example item is, “Yesterday I found real enjoyment in my job.” To measure counterproductive work behavior during the previous working day, we used a 23-item checklist (no or yes) adapted from Belmi et al. (2015) and Raelin (1994). Examples of counterproductive work behavior include damaging company property, wasting materials, blaming others, ignoring those who needed help, and badmouthing the firm. The use of a self-rated counterproductive work behavior measure is not uncommon (Berry et al., 2007; Judge et al., 2006; Mount et al., 2006; Yam et al., 2018), in part because such ratings have less observability bias than non-self-report measures (Carpenter et al., 2017). The checklist format also decreased the perceptual biases in the self-reports, as the participants only needed to indicate whether or not they had displayed each of the described behaviors.

The effects of wish-making may depend on one's religiousness, as highly religious people may experience stronger positive effects of wish-making or often make their wishes through prayers. Coping research has also shown that some people may cope through religion (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005). We thus controlled for religiousness, measured by three items adapted from Laird et al. (2011). An example is, “Religion is very important in my life” (α = 0.89).

Finally, to show that wish-making has predictive power above and beyond other coping strategies, we used Carver's (1997) short-form inventory (each coping strategy is captured by two items) to measure the 11 coping strategies in the COPE framework (Carver et al., 1989) that we discuss above. The participants were asked whether they had used these strategies to combat the pandemic. These coping strategies were self-distraction (e.g., “I have been turning to work or other activities to take my mind off things”; α = 0.63), substance use (e.g., “I have been using alcohol or other drugs to help me get through it”; α = 0.90), behavioral disengagement (e.g., “I have been giving up trying to deal with it”; α = 0.71), denial (e.g., “I have been refusing to believe that it has happened”; α = 0.75), venting (e.g., “I have been saying things to let my unpleasant feelings escape”; α = 0.31), acceptance (e.g., “I have been learning to live with it”; α = 0.69), humor (e.g., “I have been making jokes about it”; α = 0.81), seeking emotional support (e.g., “I have been getting emotional support from others”; α = 0.62), seeking informational support (e.g., “I have been getting help and advice from other people”; α = 0.71), active coping (e.g., “I have been taking action to try to make the situation better”; α = 0.51), and planning (e.g., “I have been trying to come up with a strategy about what to do”; α = 0.49). The overall α across the 22 items was 0.81. It is important to point out that the low reliability estimates for some of the coping scales were not surprising given that the scales only had two items each (Eisinga et al., 2013). In fact, Carver (1997) also observed reliability estimates of less than 0.70 among a majority of his two-item coping scales. Moreover, McCrae (1984) similarly observed reliability estimates in the 0.30 to 0.60 range among many of the short scales on coping.

2.3. Results

We first examined whether wish-making is distinct from other coping strategies by conducting confirmatory factor analyses. The model fit was evaluated by the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean-squared residual (SRMR) following Hu and Bentler (1998). When we specified the items to load on their respective latent constructs, the fit of the 12-factor model (wish-making and 11 coping strategies) was acceptable (χ 2 = 437.66, df = 258, p < .01, TLI = 0.92, CFI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.06). The factor loadings were all statistically significant and positive (ps < .01) on their respective factors, suggesting that our scales had acceptable psychometric properties. Crucially, we examined whether wish-making was distinctive by combining wish-making and each of the other 11 coping strategies in turn to see whether the model fit deteriorated (Edwards, 2001; James et al., 1982). The factor correlations estimated in the confirmatory factor analyses and the change in the chi-square values after combining two constructs are presented in Table 2 . We found that combining wish-making with each of the 11 coping strategies yielded poorer fits to the data than our original measurement model. Thus, wish-making and the other coping strategies were empirically distinctive.

Table 2.

Empirical distinctiveness of wish-making from other coping strategies in study 1 (the field survey).

| Factor correlation with wish-making | Change in χ2 after the two scales were combined to represent one construct | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-distraction | 0.28⁎⁎ | 124.93⁎⁎ |

| 2. Substance use | 0.17⁎ | 266.64⁎⁎ |

| 3. Behavioral disengagement | 0.19⁎ | 164.75⁎⁎ |

| 4. Denial | 0.34⁎⁎ | 186.91⁎⁎ |

| 5. Venting | 0.46⁎⁎ | 103.58⁎⁎ |

| 6. Acceptance | -0.16⁎ | 150.10⁎⁎ |

| 7. Humor | 0.03 | 163.39⁎⁎ |

| 8. Emotional support | 0.28⁎⁎ | 195.76⁎⁎ |

| 9. Informational support | 0.31⁎⁎ | 219.88⁎⁎ |

| 10. Active coping | -0.01 | 127.93⁎⁎ |

| 11. Planning | -0.01 | 120.80⁎⁎ |

Note. N = 208.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Table 3 and Fig. 1 show the standardized estimates of the structural paths. Wish-making predicted positive appraisals (β = 0.18, p < .01) beyond religiousness and other coping strategies, supporting Hypothesis 1. Positive appraisals predicted job satisfaction (β = 0.26, p < .01), supporting Hypothesis 2. Job satisfaction predicted counterproductive work behavior (β = -0.24, p < .01), supporting Hypothesis 3. Table 4 shows the mediation effects. Positive appraisals mediated the effects of wish-making on job satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.046, 95% CI = 0.004, 0.110). Job satisfaction mediated the effects of positive appraisals on counterproductive work behavior (indirect effect = -0.062, 95% CI = -0.132, -0.015). Crucially, positive appraisals and job satisfaction sequentially mediated the effects of wish-making on counterproductive work behavior (indirect effect = -0.011, 95% CI = -0.031, -0.001), supporting Hypothesis 4.

Table 3.

Standardized Structural Path Estimates in Studies 1 and 2.

| Criterion variables: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive appraisals | Job satisfaction | Counterproductive work behavior | |

| Control variables: | |||

| Religiousness | 0.23⁎⁎/0.10⁎ | ||

| Self-distraction | 0.21⁎⁎/0.01 | ||

| Substance use | -0.05/-0.07 | ||

| Behavioral disengagement | -0.17⁎/-0.05 | ||

| Denial | 0.13/0.15⁎ | ||

| Venting | -0.05/-0.09 | ||

| Acceptance | 0.14/0.13⁎ | ||

| Humor | 0.07/0.02 | ||

| Emotional support | 0.09/0.02 | ||

| Informational support | -0.15/0.04 | ||

| Active coping | 0.04/0.19⁎⁎ | ||

| Planning | 0.12/0.11 | ||

| Predictor variables: | |||

| Wish-making | 0.18⁎⁎/0.18⁎⁎ | 0.03/-0.01 | 0.05/-0.03 |

| Positive appraisals | 0.26⁎⁎/0.19⁎⁎ | 0.04/0.00 | |

| Job satisfaction | -0.24⁎⁎/-0.18⁎⁎ | ||

| Total R2 | 0.26/0.16 | 0.07/0.04 | 0.05/0.03 |

Note. N = 208 and 338 for Studies 1 and 2, respectively. In each cell, the two estimates (separated by “/”) are obtained from Studies 1 and 2, respectively.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Table 4.

Mediation relationships in studies 1 and 2.

| Mediation relationship | Indirect effect⁎⁎ | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (the field survey; N = 208) | ||

| Wish-making ➔ positive appraisals ➔ job satisfaction | 0.046a | [0.004, 0.110] |

| Positive appraisals ➔ job satisfaction ➔ counterproductive work behavior | -0.062a | [-0.132, -0.015] |

| Wish-making ➔ positive appraisals ➔ job satisfaction ➔ counterproductive work behavior | -0.011a | [-0.031, -0.001] |

| Study 2 (the field experiment; N = 338) | ||

| Wish-making ➔ positive appraisals ➔ job satisfaction | 0.034a | [0.011, 0.064] |

| Positive appraisals ➔ job satisfaction ➔ counterproductive work behavior | -0.034a | [-0.062, -0.011] |

| Wish-making ➔ positive appraisals ➔ job satisfaction ➔ counterproductive work behavior | -0.006a | [-0.013, -0.001] |

Note. All effect sizes represent standardized estimates. Direct effects, religiousness, and other coping tactics were controlled for in the estimates of indirect effects. CI = confidence intervals for the indirect effect.

p < .01.

Significant based on 95% CI.

To understand the nature of the observed indirect effects, we also examined whether wish-making had direct effects on job satisfaction and on counterproductive work behavior. Having or removing these direct effects did not significantly alter the fit of the model (p > .05). Consistent with this observation, we did not find any significant direct effects of wish-making on outcome variables, suggesting that the influence of wish-making is largely indirect. Similarly, having or removing the direct effect of positive reappraisals on counterproductive work behavior did not alter model fit (p > .05). In addition, we observed that this path was not significant.

3. Study 2: the field experiment

Study 1 used a field survey methodology, showing that naturally occurring wish-making predicted positive appraisals, which in turn predicted job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior. One main limitation of a field survey is the lack of strong causal evidence; although the measurement was separated into two days, all of the observed effects represented only snapshots of the relationships among the variables, limiting causal inferences (e.g., employees who engaged in positive appraisals might make more future-oriented wishes). To provide stronger causal evidence of the effects of wish-making on employees, we conducted a field experiment (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014; Spencer et al., 2005) in which we experimentally manipulated wish-making by the respondents at the start of their workdays. In so doing, we followed the recommended full-cycle research paradigm (Chatman & Flynn, 2005) and triangulated findings in different settings (Nosek et al., 2015; Scandura & Williams, 2000).

3.1. Samples and procedures

As in Study 1, the participants were recruited through a convenience sampling strategy that utilized our contacts and their referrals. Initially, we recruited 382 employees to participate; none of these participants had participated in Study 1. The experimental procedure was as follows. We sent the day 1 survey to the participants at around 9 a.m. on a working day and asked whether the participants were about to go to work, were on their way to work, or had just started work. Those who answered “yes” to any of these questions were retained, whereas those who answered “no” to all of them were thanked but excluded from the experiment. The retained subjects were then randomly assigned to one of the two conditions. In the treatment condition, the subjects were asked to make three future-oriented wishes that were relevant to the pandemic. To further reinforce this treatment effect, we asked the subjects to describe their picture of the future collectively created by the three wishes. In the control condition, the subjects were asked to name three items they had eaten for dinner the night before. This task was clearly irrelevant to wish-making. We checked the subjects' compliance in their responses to the manipulation and found that all of the subjects had complied completely: all of the subjects in the experimental condition had written down three wishes and all of the subjects in the control condition had written down things they ate the night before. Both groups of subjects were then asked to fill out survey questions about the manipulation check and positive appraisals. On the morning of the next working day (at around 9 a.m.), we sent the day 2 survey and asked the subjects to report their level of job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior on the previous day. A total of 172 matched responses were received for the treatment (i.e., wish-making) condition, and 166 matched responses were received for the control (i.e., dinner-item-naming) condition, comprising 338 matched responses. The mean age of the sample was 31 years old, 61% were female, 35% were married, 96% had a college education, and 56% had an organizational tenure of 1–5 years.

3.2. Measures

Table 5 shows the correlations among the study variables. The level of positive appraisals and the manipulation check were measured immediately after the experimental manipulation in the day 1 survey. The level of positive appraisals was measured by the nine items used in Study 1 (α = 0.86). Manipulation check was measured by three items (α = 0.89) created specifically for this study (e.g., “In the task, I made some wishes about the future”). Job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior were measured in the day 2 survey. Job satisfaction on the previous working day was assessed by Study 1's six items (α = 0.91). Counterproductive work behavior during the previous working day was measured by 14 items adapted from Stewart et al. (2009). The respondents were asked to report (no or yes) whether they had engaged in each of the listed counterproductive work behaviors during the previous working day. These behaviors included working more slowly than usual, taking longer breaks than usual, and ignoring instructions. As in Study 1, we controlled for religiousness using the same three items (α = 0.90). We also controlled for the same 11 coping strategies as in Study 1, again using Carver's (1997) short-form inventory: self-distraction (α = 0.41), substance use (α = 0.89), behavioral disengagement (α = 0.57), denial (α = 0.79), venting (α = 0.38), acceptance (α = 0.52), humor (α = 0.83), seeking emotional support (α = 0.61), seeking informational support (α = 0.76), active coping (α = 0.56), and planning (α = 0.49). The overall α across the 22 items was 0.80.

Table 5.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables in study 2 (the field experiment).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Wish-making (-1 = control, 1 = treatment) | – | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Positive appraisals | 0.20⁎⁎ | (0.86) | ||||||||||||||

| 3 Job satisfaction | 0.03 | 0.19⁎⁎ | (0.91) | |||||||||||||

| 4. Counterproductive work behavior | -0.03 | -0.04 | -0.18⁎⁎ | – | ||||||||||||

| 5. Religiousness | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.14⁎ | -0.01 | (0.90) | |||||||||||

| 6. Self-distraction | 0.01 | 0.14⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.12⁎ | 0.03 | (0.41) | ||||||||||

| 7. Substance use | 0.01 | -0.05 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.07 | (0.89) | |||||||||

| 8. Behavioral disengagement | 0.00 | -0.02 | -0.05 | 0.15⁎⁎ | 0.14⁎⁎ | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.40⁎⁎ | (0.57) | ||||||||

| 9. Denial | -0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.16⁎⁎ | 0.16⁎⁎ | 0.52⁎⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | (0.79) | |||||||

| 10. Venting | 0.08 | 0.07 | -0.11⁎ | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.30⁎⁎ | 0.17⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.24⁎⁎ | (0.38) | ||||||

| 11. Acceptance | 0.05 | 0.16⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.05 | -0.08 | 0.23⁎⁎ | -0.27⁎⁎ | -0.19⁎⁎ | -0.36⁎⁎ | 0.16⁎⁎ | (0.52) | |||||

| 12. Humor | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.04 | 0.12⁎ | -0.01 | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.12⁎ | 0.20⁎⁎ | 0.07 | (0.83) | ||||

| 13. Emotional support | 0.03 | 0.14⁎ | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.10 | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.13⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.11⁎ | 0.10 | (0.61) | |||

| 14. Informational support | 0.03 | 0.18⁎⁎ | -0.04 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.06 | 0.13⁎ | 0.17⁎⁎ | 0.48⁎⁎ | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.61⁎⁎ | (0.76) | ||

| 15. Active coping | 0.05 | 0.30⁎⁎ | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.40⁎⁎ | -0.08 | -0.05 | -0.03 | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.26⁎⁎ | 0.11⁎ | 0.36⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎⁎ | (0.56) | |

| 16. Planning | 0.09 | 0.25⁎⁎ | -0.02 | 0.04 | -0.01 | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.32⁎⁎ | 0.12⁎ | 0.13⁎ | 0.35⁎⁎ | 0.50⁎⁎ | 0.45⁎⁎ | (0.49) |

| Mean | 0.02 | 3.60 | 3.14 | 3.15 | 2.29 | 3.30 | 1.64 | 2.50 | 2.19 | 3.12 | 3.81 | 2.85 | 3.26 | 3.37 | 3.54 | 3.36 |

| SD | 1.00 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 2.91 | 0.98 | 0.68 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.95 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.57 | 0.64 |

Note. N = 338.

p < .01.

p < .05.

3.3. Results

The experimental manipulation was successful. The employees in the treatment condition reported a higher level of wish-making (M = 4.54, SD = 0.51) than those in the control condition (M = 3.45, SD = 0.72). The mean difference was significant (F (1, 336) = 258.51, p < .01).

The structural path estimates are again presented in Table 3 and Fig. 1. The experimental manipulation (-1 = control, 1 = treatment) predicted positive appraisals (β = 0.18, p < .01) beyond religiousness and other coping strategies, supporting Hypothesis 1. Positive appraisals predicted job satisfaction (β = 0.19, p < .01), supporting Hypothesis 2. Job satisfaction, in turn, predicted counterproductive work behavior (β = -0.18, p < .01), supporting Hypothesis 3. Table 4 shows that positive appraisals mediated the effects of the experimental manipulation on job satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.034, 95% CI = 0.011, 0.064). Job satisfaction, in turn, mediated the effects of positive appraisals on counterproductive work behavior (indirect effect = -0.034, 95% CI = -0.062, -0.011). Importantly, positive appraisals and job satisfaction sequentially mediated the effects of the experimental manipulation on counterproductive work behavior (indirect effect = -0.006, 95% CI = -0.013, -0.001), supporting Hypothesis 4.

In the final analysis, we coded the wishes of those respondents in the treatment condition (N = 172) based on whether the three wishes they made were lowly future-oriented (e.g., “I wish I can travel soon.”) or highly future-oriented (e.g., “I wish my family and friends will be healthy forever”). We then averaged the scores of the three wishes' future orientation. We found that the future orientation of wishes did not have significant correlations with the wish-makers' positive appraisals, job satisfaction, and counterproductive work behavior (ps > .05). We used a similar approach to code whether the wishes made by the experimental subjects were unrealistic (e.g., “I wish the whole world can have good health”) or realistic (e.g., “I wish the vaccines will be available soon”). We again found that this attribute of a wish was not significantly related to any of our study variables (ps > .05). These results perhaps suggest that it is the action of making future-oriented wishes, rather than the content of those wishes, that generated beneficial effects.

As in Study 1, we did not observe any significant direct effects of wish-making on job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior, and we did not observe any significant direct effects of positive appraisals on counterproductive work behavior. In summary, the results of the field experiment supported all of the study hypotheses. These results not only converged with those of Study 1's field survey but also provided causal evidence to suggest that whether or not employees engaged in wish-making at the beginning of their working day made a significant difference to their cognitive appraisals, job satisfaction, and counterproductive work behavior.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for theory development

We advance theory development in coping research by uncovering how wish-making can facilitate a cognitive–affective internal process, as described by cognitive appraisal theory, that allows employees to cope better with the pandemic, at least psychologically. This cognitive–affective internal process demonstrates why wish-making matters to employees. Wish-making facilitates positive appraisals of the pandemic, which create a positive mental frame. When individuals carry this positive mental frame into the work domain, they are likely to focus on the positive aspects of the workplace, thereby experiencing greater job satisfaction. Job satisfaction can lower counterproductive work behavior, illustrating that wish-making can have important implications beyond influencing an internal cognitive–affective process; it can also affect a crucial form of employee behavior, thereby influencing organizational productivity. Wish-making has direct effects only on positive appraisals but not on job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior. Thus, this coping strategy most immediately draws cognitive outcomes and draws affective and behavioral outcomes indirectly.

We do not intend to suggest that wish-making is in itself an adequate way for individuals to cope with the pandemic. Other coping strategies remain important as a response to a health threat (Rippetoe & Rogers, 1987). In both Studies 1 and 2, we measured 11 common coping strategies (Carver, 1997) and observed that self-distraction, denial, acceptance, and active coping could also promote positive appraisals. One's religiousness also exerted a positive influence. Hence, individuals often need multiple coping strategies. However, wish-making remained a significant predictor of positive appraisals even after we controlled for all of the other coping tactics and religiousness. Wish-making and positive appraisals thus appear to have a robust relationship, indicating the former's importance to coping research. Wish-making is not only conceptually different from other coping tactics but also unique in that it both alleviates the emotional consequences of a stressor (by directing individuals to the vision of a positive future) and potentially promotes goal-oriented behaviors (by making salient what one's life goals are).

Taken together, we extend coping research by identifying a new and influential coping tactic that has been largely overlooked in coping studies. Although many coping tactics have been identified (Skinner et al., 2003), wish-making has not been formally examined before. This is unfortunate because wish-making is likely to occur quite frequently due to its ease of use, and yet there have been no focused theoretical inquiries into the cognitive, affective, and behavioral effects of wish-making. In their review of the coping literature, Folkman and Moskowitz (2004) specifically highlight the importance of advancing scholarly knowledge about coping strategies that are future-oriented (e.g., coping with an anticipated stressor). Wish-making can be considered an additional type of future-oriented coping tactic because people look into the future when they make wishes. We are the first to gather supporting evidence from both field surveys and experiments that shows that wish-making can spark the onset of a functional cognitive–affective sequence that determines employees' job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior, even after controlling for the influences of other common coping strategies. In future theory development on employee coping, researchers must consider whether employees may have adopted wish-making as a way to cope with the stress in their life. More broadly, to avoid omission error, researchers should include wish-making as one of the possible coping tactics, especially when they intend to investigate a spectrum of such tactics.

4.2. Study limitations

Interpretations of this study's findings should take the following limitations into account. First, as shown in Table 1, Table 5, the correlational effects observed in this study were not strong, which is not surprising given that wish-making is one of the many coping tactics available. Importantly, we showed that wish-making is distinct from existing coping strategies and has predictive power above and beyond them. Second, although cognitive appraisals were the main reason for the effect of wish-making on job satisfaction, other cognitive or affective mechanisms may also explain this relationship. Third, the design of the experiment and field survey can be further strengthened in future research to address issues such as how long the effects of the manipulation last, whether there are other cognitive and affective mediators that explain the effects of wish-making on positive appraisals, and the conditional effects of wish-making. Fourth, we focused on counterproductive work behavior as the behavioral outcome of interest, although it is possible that job satisfaction affected other behaviors. The pandemic might have created both incentives (e.g., less monitoring) and disincentives (e.g., greater job insecurity) for employees to engage in counterproductive work behavior, making this behavioral outcome especially relevant to this study. Fifth, we used a 2-day design to reduce common method variance. An even stronger design would involve separating the four core variables in the proposed model and measuring them on four separate occasions. As the pandemic has created substantial uncertainty potentially leading to higher attrition rates, among other challenges, we decided to limit the data collection effort to just 2 days. Fortunately, we used both experimental and survey methods in two locations to triangulate our findings, and the results generally supported our hypotheses. Sixth, we used self-rated counterproductive work behavior as the only source of ratings. As noted previously, self-ratings have an important benefit; they suffer from relatively little observability bias as individuals themselves should have the most accurate knowledge on whether they have engaged in an act of counterproductive work behavior.

Another limitation was the inability to differentiate a subset of counterproductive work behavior relevant to those who were working from home during the pandemic. For these individuals, some acts of counterproductive work behavior, such as damaging company property, may be less relevant; other acts of counterproductive work behavior, such as taking longer breaks, may be more relevant for such employees. In our samples, we asked the respondents to report in the day 1 survey whether they were working from home that day. In Study 1, 31% reported that they were working from home and 30% reported that they were working from home in Study 2. In Study 2 (but not in Study 1), working from home (1 = no, 2 = yes) was positively related to counterproductive work behavior (r = 0.17, p < .01); those who worked from home reported more instances of counterproductive work behavior. Fortunately, in Study 2, job satisfaction still negatively predicted counterproductive work behavior (p < .01) even after we controlled for work-from-home arrangements, suggesting that our findings remained robust.

A final limitation is the exclusion of variables of individual differences (except for religiousness) from the study. For instance, some personality traits may determine the choice and effectiveness of coping strategies (Bolger, 1990; Connor-Smith & Flachsbart, 2007; Hock et al., 1996). Individuals' coping abilities may also make a difference in coping effectiveness (Epstein & Katz, 1992). It is also possible that individuals with certain traits (e.g., positive affectivity, core self-evaluations) are likely to report greater job satisfaction than those without such traits (Judge et al., 1998). Future research should consider individual differences and examine how the effects of wish-making may vary across individuals.

4.3. Implications for coping with the pandemic and other challenges

The pandemic is a challenge beyond anyone's direct control; it is thus highly threatening (Hu et al., 2020; Wanberg et al., 2020) because maintaining control is a fundamental human need (Heckhausen & Schulz, 1995). We suggest that at least internally, there is one thing people can do; people can make wishes that entail developing a vision of an improved state of affairs. This focus on finding the positive aspects of the pandemic, or avoidance of only thinking about the negative aspects of the pandemic, helps people build and use a more positive mental frame from which to view it. This can have important benefits for managing their daily lives, especially in terms of managing their work. Namely, wish-makers may adopt a more positive mindset at work, which in turn may promote their job satisfaction. As job satisfaction is related to a wide range of work outcomes (including counterproductive work behavior), this cognitive–affective consequence of wish-making is an important discovery. Wish-making is also relevant to managing other life challenges, such as career setbacks, family problems, financial strains, and medical conditions. We emphasize that the wishes people make must be future-oriented. If they are merely wishful thinking or maladaptive daydreaming, such as wishing to alter the past, then individuals may actually feel worse due to regret and depression (Somer et al., 2020). We also emphasize that it is the act of making future-oriented wishes that creates a positive appraisal of the situation, regardless of the specific content of the future-oriented wishes (although such content might determine the intensity of the subsequent goal-setting in life). When wish-makers can summon a positive and optimistic state of mind through their wishes, they are more likely to be able to psychologically combat the challenges and obstacles they encounter in their lives.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Thomas Ng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Analyses, Writing.

Dennis Hsu: Methodology, Analyses.

Frederick Yim: Reference Checking, Proofreading.

Yinuo Zou: Reference Checking, Proofreading.

Haoyang Chen: Reference Checking, Proofreading.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Aalto A., Harkapaa K., Aro A.R., Rissanen P. Ways of coping with asthma in everyday life: Validation of the asthma specific coping scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:1061–1069. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis H., Bradley K.J. Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods. 2014;17:351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar S. The distinction between needs and wishes: Implications for psychoanalytic theory and technique. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 1999;47:113–151. doi: 10.1177/00030651990470010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhan J.H. A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The coping strategy indicator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:1066–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Ano G.G., Vasconcelles E.B. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:461–480. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babad E., Hills M., O’Driscoll M. Factors influencing wishful thinking and predictions of election outcomes. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1992;13:461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Belmi P., Barragan R.C., Neale M.A., Cohen G.L. Threats to social identity can trigger social deviance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2015;41:467–484. doi: 10.1177/0146167215569493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R.J., Robinson S.L. In: Organizational behavior: The state of science. 2nd ed. Greenberg J., editor. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. The past, present and future of workplace deviance research; pp. 247–281. [Google Scholar]

- Berry C.M., Ones D.S., Sackett P.R. Interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and their common correlates: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92:410–424. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorck J.P., Cohen L.H. Coping with threats, losses, and challenges. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1993;12:56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N. Coping as a personality process: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:525–537. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts M.M., Becker W.J., Boswell W.R. Hot buttons and time sinks: The effects of electronic communication during nonwork time on emotions and work-nonwork conflict. Academy of Management Journal. 2015;58:763–788. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter N.C., Rangel B., Jeon G., Cottrell J. Are supervisors and coworkers likely to witness employee counterproductive work behavior? An investigation of observability and self-observer congruence. Personnel Psychology. 2017;70:843–889. [Google Scholar]

- Carver C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C.S., Scheier M.F., Weintraub J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C.S., Pozo C., Harris S.D., Noriega V., Scheier M.F., Robinson D.S., Ketcham A.S., Moffat F.L., Jr., Clark K.C. How coping mediates the effects of optimism on distress: A study of women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:375–391. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatman J.A., Flynn F.J. Full-cycle micro-organizational behavior research. Organizational Science. 2005;16:434–447. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves C., Vazquez C., Hervas G. Positive interventions in seriously-ill children: Effects on well-being after granting a wish. Journal of Health Psychology. 2016;21:1870–1883. doi: 10.1177/1359105314567768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire A., Barlow J., Powell L. Coping using positive reinterpretation in parents of children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15:801–810. doi: 10.1177/1359105310369993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith J.K., Flachsbart C. Relations between personality and coping: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:1080–1107. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crede M., Chernyshenko O.S., Stark S., Dalal R.S., Bashshur M. Job satisfaction as mediator: An assessment of job satisfaction’s position within the nomological network. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2007;80:515. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal R.S. A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2005;90:1241–1255. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J.R. Multidimensional constructs in organizational behavior research: An integrative analytical framework. Organizational Research Methods. 2001;4:144–192. [Google Scholar]

- Eisinga R., te Grotenhuis M., Pelzer B. The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health. 2013;58:637–642. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler N.S., Parker J.D.A. Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:844–854. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.5.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein S., Katz L. Coping ability, stress, productive load, and symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:813–825. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein S., Meier P. Constructive thinking: A broad coping variable with specific components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:332–350. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers A.W.M., Kraaimaat F.W., van Lankveld W., Jongen P.J.H., Jacobs J.W.G., Bijlsma J.W.J. Beyond unfavorable thinking: The illness cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1026–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R.S. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1980;21:219–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R.S. If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48:150–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R.S. Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:466–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Moskowitz J.T. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R.S., Gruen R.J., DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:571–579. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganson K.T., Tsai A.C., Weiser S.D., Benabou S.E., Nagata J.M. Job insecurity and symptoms of anxiety and depression among U.S. young adults during COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2021;68:53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N., Spinhoven V.K.P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:1311–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Grant A.M., Mayer D.M. Good soldiers and good actors: Prosocial and impression management motives as interactive predictors of affiliative citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2009;94:900–912. doi: 10.1037/a0013770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben J.R.B., Bowler W.M. Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92:93–106. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead M., Johnson S.B., Cunningham W. Measuring coping in adolescents: An application of the ways of coping checklist. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;22:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison D.A., Newman D.A., Roth P.L. How important are job attitudes? Meta-analytical comparisons of integrative behavioral outcomes and time sequences. Academy of Management Journal. 2006;49:305–325. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen H., Kuhl J. In: Goal-directed behavior: The concept of action in psychology. Frese M., Sabini J., editors. Eribaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1985. From wishes to action: The dead ends and short cuts of the long way to action; pp. 134–159. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J., Schulz R. A life-span theory of control. Psychological Review. 1995;102:284–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock M., Krohne H.W., Kaiser J. Coping dispositions and the processing of ambiguous stimuli. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1052–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to unparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., He W., Zhou K. The mind, the heart, and the leader in times of crisis: How and when COVID-19-triggered mortality salience relates to state anxiety, job engagement, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2020;105:1218–1233. doi: 10.1037/apl0000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsheger U.R. From dawn till dusk: Shedding light on the recovery process by investigating daily change patterns in fatigue. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2016;101:905–914. doi: 10.1037/apl0000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson R.D., Olekalns M., Erwin P.J. Affectivity, organizational stressors, and absenteeism: A causal model of burnout and its consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1998;52:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- James L.R., Tetrick L.E. Confirmatory analytic tests of three causal models relating job perceptions to job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1986;71:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- James L.R., Mulaik S., Brett J.M. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1982. Causal analysis: Assumptions, models, and data. [Google Scholar]

- Judge T.A., Locke E.A., Durham C.C. The dispositional causes of job satisfaction: A core evaluations approach. Research in Organizational Behavior. 1997;19:151–188. [Google Scholar]

- Judge T.A., Locke E.A., Durham C.C., Kluger A.N. Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1998;83:17–34. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge T.A., Scott B.A., Ilies R. Hostility, job attitudes, and workplace deviance: Test of a multilevel model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:126–138. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T. Frequently used coping scales: A meta-analysis. Stress and Health. 2015;31:315–323. doi: 10.1002/smi.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King L.A., Broyles S.J. Wishes, gender, personality, and well-being. Journal of Personality. 1997;65:49–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner A., Lechner C.M., Pavlova M.K., Silbereisen R.K. Goal engagement in coping with occupational uncertainty predicts favorable career-related outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2015;88:174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft R.G., Chaiborn C.D., Dowd E.T. Effects of positive reframing and paradoxical directives in counselling for negative emotions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1985;32:617–621. [Google Scholar]

- Krizan Z., Windschitl P.D. Wishing thinking about the future: Does desire impact optimism? Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2009;3:227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Laird R.D., Marks L.D., Marrero M.D. Religiosity, self-control, and antisocial behavior: Religiosity as a promotive and protective factor. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2011;32:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. Thoughts on the relations between emotion and cognition. American Psychologist. 1982;37:1019–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S., Folkman S. Springer; New York: 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood A., Boydstun A.E. Sticky prospects: Loss frames are cognitively stickier than gain frames. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2014;143:376–385. doi: 10.1037/a0032310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Allen N.J. Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87:131–142. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshem O.A. What you wish for is not what you expect: Measuring hope for peace during intractable conflicts. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2017;60:60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lin W., Shao Y., Li G., Guo Y., Zhan X. The psychological implications of COVID-19 on employee job insecurity and its consequences: The mitigating role of organization adaptive practices. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2021;106:317–329. doi: 10.1037/apl0000896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke E.A. What is job satisfaction? Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 1969;4:309–336. [Google Scholar]

- Martinko M.J., Zellars K.L. In: Dysfunctional behavior in organizations. Griffin R.W., O’Leary-Kelly A., Collins J.M., editors. Elsevier Science/JAI Press; 1998. Toward a theory of workplace violence and aggression: A cognitive appraisal perspective; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Masters M.A. The use of positive reframing in the context of supervision. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1992;70:387–390. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R.R. Situational determinants of coping responses: Loss, threat, and challenge. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:919–928. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath E., Cooper-Thomas H.D., Garrosa E., Sanz-Vergel A.I., Cheung G.W. Rested, friendly, and engaged: The role of daily positive collegial interactions at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2017;38:1213–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Moore S.A., Varra A.A., Michael S.T., Simpson T.L. Stress-related growth, positive reframing, and emotional processing in the prediction of post-trauma functioning among veterans in mental health treatment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Morgeson F.P., Humphrey S.E. The work design questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:1321–1339. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount M., Ilies R., Johnson E. Relationship of personality traits and counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effects of job satisfaction. Personnel Psychology. 2006;59:591–622. [Google Scholar]

- Neeleman J. The therapeutic potential of positive reframing in panic. European Psychiatry. 1992;7:135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Nosek B.A., Aarts A.A., Anderson C.J., Anderson J.E., Kappes H.B., et al. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science. 2015;349:943–951. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaccio A., Vandenberghe C. Five-factor model of personality and organizational commitment: The mediating role of positive and negative affective states. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2012;80:647–658. [Google Scholar]