Abstract

Both overt and covert narcissism are positively correlated with conspicuous consumption, which is considered to have the function of satisfying narcissists' dignity needs through showing their status. However, the two types of narcissism are related to different mental health outcomes, and the possible role of conspicuous consumption in these relations has not been explored in depth. Meanwhile, researchers have not reached a consensus on the relation between conspicuous consumption and mental health. The present study recruited a sample of 480 college students to explore the above problems. The correlation analysis showed that both types of narcissism were positively correlated with conspicuous consumption and external value. Overt narcissism was positively correlated with meaning in life, whereas covert narcissism showed the contrary. Conspicuous consumption was negatively correlated with meaning in life but positively correlated with external value. The mediating analysis revealed that neither type of narcissism could help individuals obtain meaning in life through conspicuous consumption directly; however, covert narcissism could help obtain external value through conspicuous consumption for securing meaning in life, whereas overt narcissism could not. The differences between the two types of narcissism and their relation with conspicuous consumption and meaning in life are discussed.

Keywords: Narcissism, Meaning in life, Conspicuous consumption, External value

Narcissism; Meaning in life; Conspicuous consumption; External value

1. Introduction

1.1. Meaning in life

Meaning in life refers to the sense of feeling meaning and value with respect to one's life or recognizing that life has a clear goal, mission, or purpose. In other words, meaning in life is a cognitive evaluation of whether one's life is meaningful (Martela and Steger, 2016). Numerous studies have shown that the sense of meaning in life is an important indicator of individuals' mental health (King and Hicks, 2021; Zhao et al., 2017). A higher level of this sense is significantly related to a higher level of happiness, self-worth, self-esteem (Boyle et al., 2010; Schulenberg et al., 2014). On the contrary, a low level of the sense of meaning in life is a direct cause of depression. Individuals with a low level of this sense tend to give up their efforts when faced with pressure and are prone to feelings of emptiness, boredom, and helplessness. They are prone to frustration, have more anxiety and substance abuse issues, and are more likely to die from suicide (Littman-Ovadia and Steger, 2010; Wilchek-Aviad, 2015). In view of the important role of the meaning in life on individuals' physical and mental health, its influencing factors merit exploration. For one, personality is the basis of individuals' experience of meaning in life (Burton et al., 2015), and personality traits are considered important influencing factors of meaning in life (Zhao et al., 2017).

1.2. Narcissism

Narcissism is a personality trait commonly found in the population (Twenge and Foster, 2010; Guo et al., 2016; Hamamura, 2018). Individuals with such a trait typically have a high level of egocentrism; they have positive perceptions of themselves that are not in line with the actual situation. They are also extremely eager for the attention and appreciation of others (Campbell and Miller, 2013). In recent years, people are reportedly becoming more narcissistic, especially in younger groups (Back et al., 2013; Neave et al., 2020). Regarding the structure of narcissism, most psychologists believe that narcissism can be divided into two types: overt and covert narcissism (Wink, 1991). Both types of narcissism have the characteristics of self-exaggeration and extreme desire for other people's attention and appreciation, but they also have notable differences. Overt narcissists are generally independent, outgoing, cheerful, and confident. They have positive self-concepts and a very direct desire to express themselves. They pay attention to success and always need the attention and envy of others. Meanwhile, covert narcissists have a potential inferiority complex. They are overly sensitive, anxious, insecure, and feel that they are inferior to others, but they also exaggerate themselves unconsciously. Numerous studies have shown that overt and covert narcissism have different associations with mental health (Zheng and Huang, 2005). The former is positively related to a variety of mental health indicators, such as self-esteem, life satisfaction, and subjective well-being (Ng et al., 2014), whereas the latter is more positively related to psychological abnormalities, such as anxiety, low self-esteem, and depression (Rathvon and Holmstrom, 1996; Yu and Song, 2018).

1.3. Narcissism, external value, and meaning in life

Recent research has indicated that overt narcissism is positively correlated with the sense of meaning in life, and it can positively predict an individual's sense of meaning in life through significance (Womick et al., 2020). Significance, one of the three components of meaning in life, refers to the feeling that life is worth living. When individuals discover that their own existence is important to others and to the world at large, they can experience significance (George and Park, 2016). Because it essentially expresses individuals' perception of their own value in the objective physical world, significance is also called external value (Li et al., 2021). Therefore, the present study adopted the term “external value” to refer to significance.

Recent studies have shown that the acquisition of external value may be the most important way for individuals to gain a sense of meaning in life (Costin and Vignoles, 2020). For narcissists to satisfy their own external value needs, conspicuous consumption has been noted to be an important means (Sedikides et al., 2013).

1.4. Narcissism, conspicuous consumption, external value, and meaning in life

Conspicuous consumption refers to the consumption behavior of individuals of showing off their wealth by purchasing expensive and fancy products (e.g., high-end cars, jewelry, fashionable clothing) to attract attention and prove their social status to others (Veblen, 2011). The essence of this behavior is to obtain a more positive self-evaluation and a higher level of self-esteem, thereby meeting the value needs of narcissistic individuals. Studies have found a positive correlation between narcissism and conspicuous consumption. Narcissistic individuals engage in conspicuous consumption to satisfy their own dignity and honor needs, particularly for protecting and enhancing their social status (Taylor and Strutton, 2016; Velov et al., 2014). Therefore, we speculated that narcissistic individuals can satisfy their external value needs through conspicuous consumption.

However, researchers have not come to a consensus on the relation between conspicuous consumption and individuals' mental health (e.g., life satisfaction and subjective well-being). Studies exploring this theme in Chinese groups are also scarce. Indeed, no research has directly explored the relation between meaning in life and conspicuous consumption. Meaning in life is considered a typical representative of Eudaimonia, which can reflect the individual's mental health better than Hedonia (e.g., subjective well-being and life satisfaction) (King and Hicks, 2021; Yang et al., 2016). As such, exploring the relation between conspicuous consumption and meaning in life in a Chinese sample can not only enrich the relevant research in China but also contribute to a clearer understanding of the relation between the two. Specifically, we hypothesized that conspicuous consumption is negatively correlated with meaning in life and narcissists cannot acquire meaning in life directly through conspicuous consumption. Regarding external value, which is considered to be the most important source of meaning in life (Costin and Vignoles, 2020; Li et al., 2021), we also speculated that if conspicuous consumption can satisfy the external value needs of narcissistic individuals, then these individuals can acquire meaning in life.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 521 volunteer students from northern China were recruited online through the survey platform Wenjuanxing (https://www.wjx.cn), which is an online platform similar to Amazon's Mechanical Turk. It is known to be a reliable tool for data collection in China. We opted to recruit college students to ensure that our participants had a sum of money every month that they could spend freely (in the form of allowance or income from part-time jobs). We adopted a convenient sampling method; the data were obtained from online panelists. All participants gave informed consent and agreed to participate in the study. After completing the questionnaire, the participants received either 10 RMB in cash or in shopping coupons. This study was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University.

In the questionnaire, we included three test questions that were designed to judge whether the participants answered the items carefully. The three test questions were set at irregular intervals and participants were asked to choose the answers we specified, such as “This is a test of attention. Please choose the third option.” If a participant chose the answer we specified, then they were judged to have completed the questionnaire carefully, which we took to indicate the validity of the questionnaire responses. The questionnaire took about 480 s to complete. Finally, after excluding the questionnaires with incomplete answers, we obtained 480 valid questionnaires, accounting for an effective response rate of 92.13%. Among them, 231 were men and 249 were women, with an average age of 19.70 years (standard deviation = 2.47 years).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Global Meaning in Life Questionnaire (GMLQ)

The GLMQ is a four-item, self-reported, and validated questionnaire designed to assess an individual's sense of meaning in life (Costin and Vignoles, 2020). The scale is composed of four descriptions, with two positively worded and two negatively worded sentences. For avoiding to mention specific meaning components, the GMLQ grasps the entire content by which people judge their overall life as meaningful or not. It has been proven to have good reliability and validity in the Chinese population (Li et al., 2021). Therefore, we used GMLQ as the tool to assess for global sense of meaning. The total scale had a Cronbach's α of 0.89.

2.2.2. Narcissism scale

The Narcissism Scale is a 35-item, self-reported, and validated questionnaire designed to assess an individual's level of narcissism (Zheng and Huang, 2005). The scale has two dimensions: overt and covert narcissism. The scale has been proven to have good reliability and validity in the Chinese population (Min and He, 2015). The overt narcissism subscale contains the four dimensions of power, superiority, privilege, and self-envy, such as “I know I am excellent, because everyone says I am born with a talent for leadership.” The covert narcissism subscale contains the three dimensions of sensitivity, privilege, and self-envy, such as “I often feel useless” and “People and things around me often make me feel very dissatisfied.” Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale. All items are summed to create the total score, with a higher score indicating a higher level of the corresponding narcissistic traits of the individual. In our sample, the Cronbach's α of the two were 0.95 and 0.80 for overt and covert narcissism.

2.2.3. External value scale

The external value scale is a four-item, self-reported, and validated questionnaire (Li et al., 2021) for measuring individuals' sense of external value. When an individual is affirmed and appreciated by others, they usually feel that their existence is important and full of value, leading the individual to experience external value. Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale. All items are summed to create a total score. The higher the score, the more valuable the individuals think their existence is. In our sample, the scale had a Cronbach's α of 0.80.

2.2.4. Conspicuous Consumption Scale

We used the Conspicuous Consumption Scale developed by Marcous (1997) and revised by Chen (2009). The scale has been confirmed to have good reliability and validity in the Chinese population (Liu and Wang, 2019). This 13-item scale includes the four dimensions of social recognition needs, herd needs, identity characteristics, and image needs. Example items are “People buy famous brands to make a good impression on others” and “People want to own brand-name products owned by their friends and colleagues.” The tool uses a seven-point Likert scoring scale. In our study, the total scale had a Cronbach's α of 0.95.

2.3. Statistical analyses

We used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 for descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis among the variables. We tested for mediating effects using Process (v3.3) (Hayes, 2013). We also used Harman's single factor test to test the common method deviation. The results showed that the variance predicted by the first factor was 34.55%, or lower than the critical standard of 40%. Therefore, the study did not have any serious common method biases.

3. Results

As shown in Table 1, the level of conspicuous consumption in men was higher than that in women, and age was negatively correlated with conspicuous consumption. Both overt and covert narcissism were positively correlated with conspicuous consumption and external value. Overt narcissism was positively correlated with the sense of meaning in life, whereas covert narcissism showed the opposite tendency.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Age | 0.09 | 1 | |||||

| 3. Overt narcissism | -0.31∗∗ | -0.24∗∗ | 1 | ||||

| 4. Covert narcissism | -0.20∗∗ | -0.27∗∗ | 0.70∗∗ | 1 | |||

| 5. Conspicuous consumption | -0.24∗∗ | -0.24∗∗ | 0.65∗∗ | 0.66∗∗ | 1 | ||

| 6. External value | -0.18∗∗ | -0.13∗∗ | 0.57∗∗ | 0.12∗∗ | 0.17∗∗ | 1 | |

| 7. Meaning in life | -0.08 | 0.11∗ | 0.23∗∗ | -0.23∗∗ | -0.16∗∗ | 0.53∗∗ | 1 |

Note: N = 480, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, Sex: 1 = Male, 2 = Female.

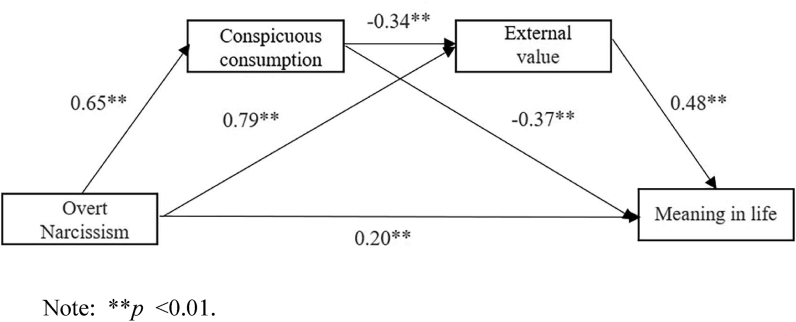

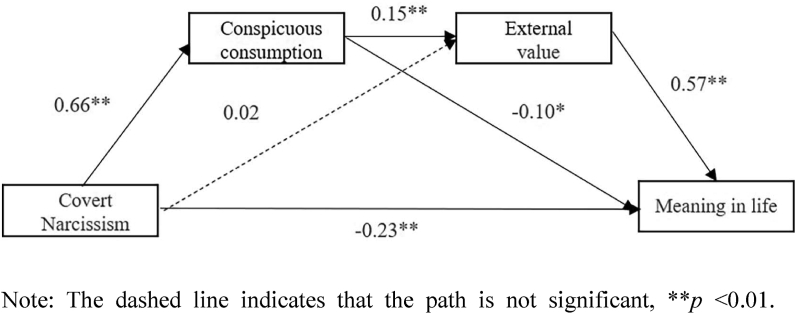

We used the Process macro (v3.3, model 6) developed by Hayes (2013) for Bootstrap (5000) to test the mediation effects (Wen and Ye, 2014), with the results shown in Figures 1 and 2. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the chain mediation of overt narcissism through conspicuous consumption and external value to the sense of meaning in life was [-0.155, -0.063], and the negative chain mediation effect was significant. The 95% CI of the chain mediation from covert narcissism through conspicuous consumption and external value to sense of meaning in life was [0.005, 0.128], and the positive chain mediation effect was significant.

Figure 1.

Meditating effect of conspicuous consumption and external value between overt narcissism and meaning in life. Note: ∗∗p < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Meditating effect of conspicuous consumption and external value between covert narcissism and meaning in life. Note: The dashed line indicates that the path is not significant, ∗∗p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

4.1. Relation between narcissism, conspicuous consumption, external value, and meaning in life

First, the results showed that the level of conspicuous consumption in men was higher than that in women, which may be because men have a higher level of narcissism than women. Individuals with stronger narcissism are more likely to make conspicuous consumption (Taylor and Strutton, 2016). Meanwhile, the level of conspicuous consumption decreased with age. On the one hand, individuals' narcissism decreased with age and their meaning in life increased with age; these factors may work together to reduce individuals' conspicuous consumption. On the other hand, some researchers have argued that the younger the individual is, the more likely they would be easily influenced by others and choose conspicuous consumption. However, the consumption tendency of individuals change from conspicuous to practical with age, and as such, the level of conspicuous consumption tends to decrease with age (Shi, 2020).

Second, we found that the sense of meaning in life was positively correlated with overt narcissism but negatively correlated with covert narcissism, consistent with previous findings (Hou et al., 2020; Wink, 1991). Overt narcissists are confident and have exaggerated cognition of themselves. They have a higher level of self-esteem, enabling them to participate actively in interpersonal communication and work in daily life. These may explain their higher level of meaning in life. Although covert narcissists also tend to exaggerate themselves and think they are superior to others, their level of self-esteem is very low. They are highly sensitive to the evaluation of others and often fall into bouts of anxiety and self-doubt. Therefore, their sense of meaning in life is also very low. Nonetheless, both overt and covert narcissism are positively correlated with external value, given the characteristics of narcissism itself. Overt narcissists always have an overly positive view of themselves, and although covert narcissists generally have a potential inferiority complex, they also exaggerate themselves, albeit unconsciously (Wink, 1991; Zheng and Huang, 2005). Both overt and covert narcissists want to prove and show their superiority to others, which means they think they are more valuable than other people.

Meanwhile, external value refers to the feeling that one's life is of significance, importance, and value in the world (George and Park, 2016). Therefore, both overt and covert narcissism showed a positive correlation with external value. In addition, the essence and goal of conspicuous consumption is to obtain a more positive self-evaluation and a higher level of self-esteem through proving one's social status to others (Veblen, 2011), which is also an expression of value showing. Thus, conspicuous consumption was positively correlated with external value.

Lastly, we found that conspicuous consumption was negatively correlated with meaning in life. This may be due to the fact that conspicuous consumption typically carries negative outcomes, such as economic pressure, and is often regarded as a negative behavior in Chinese culture (Sun and Sun, 2021).

4.2. Mediating role of conspicuous consumption and external value

First, the results showed that both overt and covert narcissists could not obtain meaning in life directly through conspicuous consumption. Although conspicuous consumption may protect or enhance individuals' self-esteem, its negative effects (e.g., economic pressure) and image as unhealthy behavior in Chinese culture (Sun and Sun, 2021) may work together to hinder people from experiencing meaning in life.

Second, overt narcissists can experience meaning through external value but covert narcissists cannot, which may be due to the difference between the two types of narcissism. Overt narcissists tend to have positive self-evaluation and high self-esteem; therefore, the level of their external value is relatively high (Zheng and Huang, 2005). They can experience meaning through their external value, even if their evaluation of their own value is not consistent with the actual situation, to a certain extent. However, although covert narcissists may unconsciously exaggerate themselves, the level of their self-esteem is low, and they are always overly sensitive and anxious (Wink, 1991). Therefore, the level of covert narcissists' external value is relatively low, leading to them failing to obtain meaning through their external value.

Third, we found that covert narcissists can obtain the sense of meaning in life through conspicuous consumption to satisfy their external value needs, but overt narcissists cannot. This result highlights the difference between the two types of narcissism and sheds lights on the source of meaning in life. As a positive part of the narcissistic individual, meaning in life is acquired by overt narcissists through a relatively positive manner. For example, studies have found a positive correlation between overt narcissism and positive emotions and pro-social behaviors (Zhao et al., 2017). These behaviors have been proven to be important for gaining a sense of meaning in life (Ding et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017). As such, overt narcissism may have a more positive impact on individuals' behavior (compared with covert narcissism), and overt narcissists are more likely to choose a relatively positive way to acquire meaning. As conspicuous consumption is generally considered a negative consumption behavior in Chinese culture (Sun and Sun, 2021), we found that overt narcissists cannot gain meaning in life through conspicuous consumption, whereas covert narcissists can. This result indicates the negative nature of covert narcissism to a certain degree. Given their low self-esteem, covert narcissistic individuals are afraid to enhance their self-esteem and acquire meaning in life through normal means (Zheng and Huang, 2005), such as competing head-on with others. They are more likely to attempt to gain the respect and approval of others through tactful and indirect approaches, such as conspicuous consumption. Although conspicuous consumption is generally considered unhealthy behavior, it can nonetheless bring meaning for individuals through the realization or acquisition of external value. Thus, the positive and negative effects of conspicuous consumption should be evaluated from a neutral standpoint. Moreover, this result clarifies that the essence of the meaning in life is subjective experience. King and Hicks (2021) mentioned that meaning in life is essentially an individual's subjective experience. When individuals report that they have the meaning of life, no matter what the meaning they mean, it is of great significance to individuals. Although meaning in life is generally regarded as noble and rare by theorists, it should be regarded from a more objective perspective, as well as the manner to acquire it. The acquisition of external value may be the most important way for individuals to obtain meaning in life (Costin and Vignoles, 2020; Womick et al., 2020), but the way to obtain external value varies among people. For some people, helping others makes them feel they are valuable. For others, ridiculing or belittling others may make them feel valuable. This diversity may be explained by the influence of opinions on value or culture. When studying the typical behaviors of personality types in the future, we can consider the influence of world outlook and values and their effects on the individual's satisfaction of self-worth.

Meanwhile, our study further clarified some negative impacts of conspicuous consumption among Chinese youth groups. Regarding the relation between conspicuous consumption and individual mental health, researchers have not reached a consistent conclusion. Gordon et al. (2019) reported that conspicuous consumption is positively correlated with an individual's life satisfaction; an increase in conspicuous consumption can increase individual's happiness relative to non-conspicuous consumption. This result has been verified in surveys in Belgium and Australia (Hudders and Pandelaere, 2012; Wu, 2020). However, other researchers' investigations in countries such as India and Thailand have yielded contradictory results. Conspicuous consumption is positively correlated with lower life satisfaction and worse subjective well-being (Herberholz and Prapaipanich, 2019; Linssen et al., 2011). Meanwhile, in the context of China, few studies have examined the relation between conspicuous consumption and mental health. Only one study, conducted in college students, found that conspicuous consumption is negatively correlated with individuals' subjective well-being (Liu and Wang, 2019). We opted to focus on the sense of meaning in life; as a typical representative of Eudaimonia, it could better reflect mental health compared with subjective well-being (King and Hicks, 2021; Yang et al., 2016). We found that conspicuous consumption was negatively correlated with the sense of meaning in life. Narcissistic individuals cannot directly obtain meaning in life through conspicuous consumption. This result reflects some negative effects of conspicuous consumption. The essence of conspicuous consumption is to satisfy individuals' pursuit of status and vanity through the purchase of expensive items. As a group that does not yet have independent income, young people's purchase of luxury or trendy brands often leads to economic pressure, which could harm their mental health (Wang et al., 2019).

For instance, some surveys in China have found that nearly 88% of college students' disposable income is less than 1,500 RMB (about 232 USD) per month (Sha et al., 2019). Although this amount can meet the basic costs of college students' school life and study, it is far from sufficient for meeting the increasing consumption desire of students. Many college students have reported taking out loans for meeting their consumption needs (Sha et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Owing to their limited social experience, they often end up taking out informal loans, such as “campus loan,” which is a type of scam (Ma, 2020). Its interest rate is extremely high; students borrow a small amount of money but need to repay several times the money borrowed. A number of college students have died from suicide after failing to repay these loans (Ma, 2020).

In addition, we speculated that the reason for the lack of consistent conclusions on the relation between conspicuous consumption and individual mental health may be the difference in the survey samples. In developed countries, individuals' income levels are relatively high, and their expected future income level is also relatively high. Even if they buy luxury goods for conspicuous consumption, they may not experience too much economic pressure. Conspicuous consumption satisfies their value needs, and they feel happy (Hudders and Pandelaere, 2012). Research in developed countries has found that conspicuous consumption is positively correlated with subjective well-being (Hudders and Pandelaere, 2012; Wu, 2020). In developing countries, the income level of individuals is relatively low, and the purpose of purchasing conspicuous goods is often for vanity (Linssen et al., 2011). Moreover, conspicuous consumption requires more resources, and individuals engaging in this behavior may easily face economic difficulties, thereby further affecting their mental health (Herberholz and Prapaipanich, 2019). In addition, the different consumption habits of people in developed and developing countries may also be an important influencing factor (Zhang, 2014). For instance, among individuals in European countries, taking out loans is a normalized behavior. Indeed, many people are in debt for life. Meanwhile, Chinese believe in being “out of debt, out of danger,” which means that only when people have no debts can they truly relax and be happy. This difference in worldview may also be an important way for conspicuous consumption to affect individuals' mental health. Therefore, cross-cultural research is an important direction in the future.

4.3. Limitations

This study has limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the findings above. We used a questionnaire survey, and the responses could have been affected by social desirability. Moreover, our sample was composed mainly of college students. Whether the results can be extended to other groups is not clear. Future research should thus expand the size and diversity of the sample. Another limitation is that our survey did not collect specific information on participants' income, which may enrich the analysis of the variables. Finally, this research used a cross-sectional design, which is essentially correlative research. In the future, longitudinal and experimental research can be conducted to supplement and verify the current results.

5. Conclusion

Although covert narcissism is negatively correlated with meaning in life, covert narcissists have their own manner to obtain meaning in life. They can obtain meaning in life through the external value brought by conspicuous consumption, whereas overt narcissists cannot. Overt and covert narcissists have different ways of acquiring meaning in life. The behavior that brings external value for people could provide them a sense of meaning in life, even if it will cause some negative outcomes at the same time.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Chengquan Zhu: Performed the experiment; Wrote the paper.

Ruiying Su: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Xun Zhang: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Yanan Liu: conceived and designed the experiments.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Henan (2019BJY021).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Back M.D., Kuefner A.C.P., Dufner M., Gerlach T.M., Rauthmann J.F., Denissen J.J.A. Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013;105(6):1013–1037. doi: 10.1037/a0034431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P.A., Buchman A.S., Barnes L.L., Bennett D.A. Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2010;67(3):304–310. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton C.M., Plaks J.E., Peterson J.B., Cohrs J.C. Why do conservatives report being happier than liberals? The contribution of neuroticism. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 2015;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- Campbell W.K., Miller J.D. In: Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Widiger T.A., Costa P.T., editors. American Psychological Association; 2013. Narcissistic personality disorder and the five-factor model: delineating narcissistic personality disorder, grandiose narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism; pp. 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Costin V., Vignoles V.L. Meaning is about mattering: evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020;118(4):864–884. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. Xiamen University; 2009. An Empirical Study of the Effects of Vanity and Money Attitudes on College Students' Propensity to Conspicuous Consumption. M.A, Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Ding R., Zhou H., Zhang B., Chen X. Narcissism and adolescents' prosocial behaviors: the role of public and private situations. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2016;48(8):981–988. [Google Scholar]

- George L.S., Park C.L. Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: toward integration and new research questions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2016;20(3):205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Guo F., Zhang Z., Yuan S., Jing Y., Wang W. The theories and neurophysiological mechanisms of narcissistic personality. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2016;(8):1246–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D.,A., Brown John, Gathergood Consumption changes, not income changes, predict changes in subjective well-being: Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2019;11(1):64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes Andrew F. The Guilford Press; NY: 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Hamamura T. A cultural psychological analysis of cultural change. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2018;21(1-2):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Herberholz C., Prapaipanich N. Conspicuous consumption of online social networking devices and subjective well-being of Bangkokians. Singapore Econ. Rev. 2019;64(5):1371–1395. [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y., Hou W., Zhou A. Cognitive processing preferences of different types of narcissists for self-related information. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2020;5:528–537. [Google Scholar]

- Hudders L., Pandelaere M. The silver lining of materialism: the impact of luxury consumption on subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2012;13(3):411–437. [Google Scholar]

- King L.A., Hicks J.A. In: Fiske S.T., editor. Vol. 72. 2021. The science of meaning in life; pp. 561–584. (Annual Review of Psychology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Liu Y., Peng K., Hicks J.A., Gou X. Developing a quadripartite existential meaning scale and exploring the internal structure of meaning in life. J. Happiness Stud. 2021;22(2):887–905. [Google Scholar]

- Linssen R., van Kempen L., Kraaykamp G. Subjective well-being in rural India: the curse of conspicuous consumption. Soc. Indicat. Res. 2011;101(1):57–72. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9635-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littman-Ovadia H., Steger M. Character strengths and well-being among volunteers and employees: toward an integrative model. J. Posit. Psychol. 2010;5(6):419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Wang L. Effects of conspicuous consumption on subjective well-being of college students: multiple mediation effects of three dimensions in locus of control. Sci. Educ. Article Cult. 2019;(3):161–163. [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J.S., Filiatrault P., Cheron E. The attitudes underlying preferences of young urban educated Polish consumers towards products made in western countries. J. Int. Consum. Market. 1997;9(4):5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Martela F., Steger M.F. The three meanings of meaning in life: distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016;11(5):531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Ma L. Shanxi Normal University; 2020. Investigation and Analysis of College Students' Conspicuous Consumption Behavior. M.A, Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Min W., He N. Relationship between middle school students' narcissism and peer relations: self-esteem as a mediator. China J. Health Psychol. 2015;23(5):772–776. [Google Scholar]

- Neave L., Tzemou E., Fastoso F. Seeking attention versus seeking approval: how conspicuous consumption differs between grandiose and vulnerable narcissists. Psychol. Market. 2020;37(3):418–427. [Google Scholar]

- Ng H.K.S., Cheung R.Y.-H., Tam K.-P. Unraveling the link between narcissism and psychological health: new evidence from coping flexibility. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2014;70:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rathvon N., Holmstrom R.W. An MMPI-2 portrait of narcissism. J. Pers. Assess. 1996;66(1):1–19. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg S.E., Baczwaski B.J., Buchanan E.M. Measuring search for meaning: a factor-analytic evaluation of the seeking of noetic goals test (SONG) J. Happiness Stud. 2014;15(3):693–715. [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C., Hart C.M., Cisek S.Z., Routledge C. Springer Netherlands; 2013. Finding Meaning in the Mirror: the Existential Pursuits of Narcissists. [Google Scholar]

- Sha M., Lu J., Wu X., Tao B., Tao S. Analysis of College Students' consumption of take-out food and family influencing factors. Chin. J. Schol. Health. 2019;40(7):1068–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Shi W. East China Normal University; 2020. How Conspicuous Consumption Affectsperceived Status. M.A, Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Sun S. Childhood socioeconomic status, life history strategy and consumption: China traditional values of “ unity and harmony” as moderator. J. Psychol. Sci. 2021;(1):126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.G., Strutton D. Does Facebook usage lead to conspicuous consumption? The role of envy, narcissism and self-promotion. J. Res. Interact. Med. 2016;10(3):231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge J.M., Foster J.D. Birth cohort increases in narcissistic personality traits among American college students, 1982-2009. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2010;1(1):99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Veblen . Commercial Press; 2011. The Theory of the Leisure Class. [Google Scholar]

- Velov B., Gojkovic V., Duric V. Materialism, narcissism and the attitude towards conspicuous consumption. Psihologija. 2014;47(1):113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Sha M., Lu J., Wu X., Tao B., Tao S. Analysis of the current situation and related factors of beverage consumption in college sports specialty. Chin. J. Schol. Health. 2019;N310(10):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z., Ye B. Analyses of mediating effects: the development of methods and models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014;22(5):731–745. [Google Scholar]

- Wilchek-Aviad Y. Meaning in life and suicidal tendency among immigrant (Ethiopian) youth and native-born Israeli youth. J. Immigr. Minority Health. 2015;17(4):1041–1048. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wink P. Two faces of narcissism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991;61(4):590–597. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womick J., Atherton B., King L.A. Lives of significance (and purpose and coherence): subclinical narcissism, meaning in life, and subjective well-being. Heliyon. 2020;6(5) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. An examination of the effects of consumption expenditures on life satisfaction in Australia. J. Happiness Stud. 2020;21(8):2735–2771. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Cheng W., Han B., Yang Z. Will searching for meaning bring well-being? Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2016;(9):1496–1503. [Google Scholar]

- Yu H.-A., Song W.y. The mediating effect of emotional clarity and ambivalence over emotional expressiveness in the relationship between college student's covert narcissism and depression [대학생의 내현적 자기애가 우울에 미치는 영향: 정서인식 명확성과 정서표현 양가성의 매개효과] J. Conv. Inf. Technol. 2018;8(3):161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N., Ma M., Xin Z. Mental mechanism and the influencing factors of meaning in life. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2017;25(6):1003–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. Xiamen University; 2014. The Distinction and Analysis of the Research on the Consumption Concept in China and the West. M.A, Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Huang L. Overt and covert narcissism: a psychological exploration of narcissistic personality. J. Psychol. Sci. 2005;28(5):1259–1262. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.