Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic has ravaged the globe in the past year, demanding shifts in all aspects of life including health profession education. The New York City area was the first major United States epicenter and is home to four genetic counseling graduate programs. We set out to explore the multifaceted programmatic changes required from the four institutions in an early pandemic epicenter, providing the longest time horizon available for assessing the implications of this restructuring on graduate education in the profession. Using practitioner‐based enquiry, our iterative reflections identified three phases of COVID‐19 response within our programs from March through December 2020. The spring months were marked by significant upheaval and reactivity, with a focus on stabilizing our programs in an unstable environment that included a significant medical response required in our area. By summer, we were reinvesting time and energy into our programs and prioritizing best practices in online learning. Relative predictability returned in the fall with noticeable improvements in flexibility and proactive problem‐solving within our new environment. We have begun to identify changes in both curricula and operations that are likely to become more permanent. Telehealth fieldwork, remote supervision, simulated cases with standardized clients, and virtual recruitment and admission events are some key examples. We explored early outcome measures, such as enrollment, retention, course evaluations, and student academic and fieldwork progress, all indicating little change from prior to the pandemic to date. Overall, we found our programs, and genetic counseling graduate education more broadly, to be much more resilient and flexible than we would ever have realized. The COVID‐19 pandemic has awakened in us a desire to move ahead with reduced barriers to educational innovation.

Keywords: COVID‐19, curriculum, education, genetic counseling, practitioner‐based enquiry, program evaluation

What is known about this topic

Personal communications from genetic counseling graduate programs indicate that significant restructuring of curriculum and program operations has occurred within genetic counseling graduate programs in the wake of the COVID‐19 pandemic primarily due to social distancing requirements and other public health measures.

What this paper adds to the topic

To our knowledge, there are no published reports of the impact of COVID‐19 on genetic counseling graduate programs. This paper explores the multifaceted programmatic changes required from the four institutions in an early pandemic ‘hot spot’, providing the longest time horizon available for assessing the implications of this restructuring on graduate education in our field.

1. INTRODUCTION

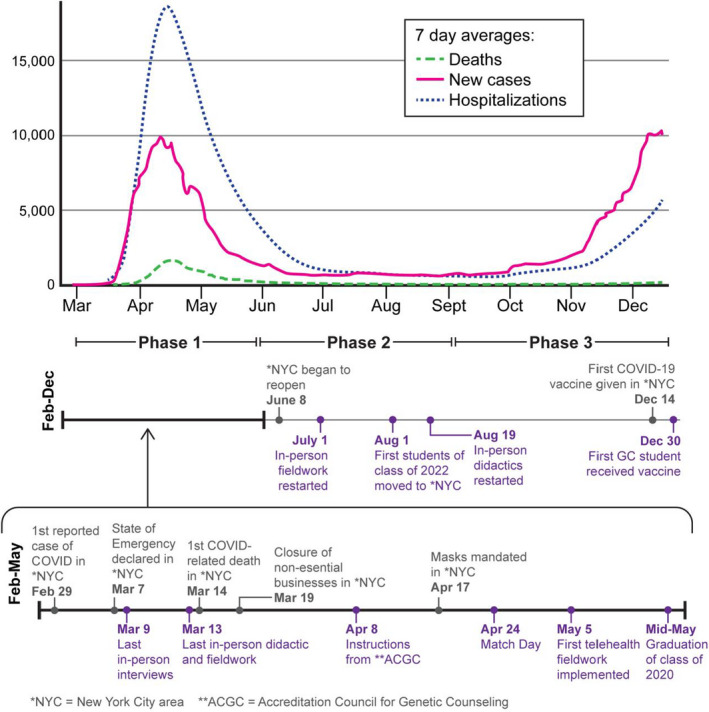

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) has ravaged the globe in the past year, with more than 168 million diagnosed cases worldwide resulting in more than 3.4 million deaths (WHO, 2021) at the time of submission. The New York City area (NYC) was the first major United States (US) epicenter, with an exponential growth in cases from the first diagnosis on February 29, 2020 until the apex of related hospitalizations in mid‐April 2020. During this time, NYC continued to reach multiple grim COVID‐19 milestones (Figure 1). While COVID‐19 has demanded shifts in health profession education across the US, NYC programs had no choice but to shift first and fast due not only to their geographic location in an early epicenter but also the immense, unprecedented demands on the city‐wide healthcare system and the direct challenge to both institutional and personal capacity in managing this public health crisis.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of major COVID‐related events impacting NYC. Comparison of timing of major genetic counseling program and city‐wide milestones related to the COVID‐19 pandemic with the rate of infection, hospitalization, and death in New York as reported by The New York Times

NYC is home to four of the United States’ 51 nationally accredited genetic counseling graduate programs, at Sarah Lawrence College, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Long Island University Post, and Columbia University. These programs span a range of longevity in genetic counseling graduate education, opening in 1969, 1991, 2009, and 2019, respectively. Two programs are located within large medical center campuses in the heart of NYC and two on suburban campuses at the outskirts of the city. Together, these programs represent 7.8% of all accredited programs in the United States and are currently training 13.2% (126/958) of all genetic counseling graduate students.

Multiple health profession education programs have reported their experiences regarding curriculum adaptation in the wake of COVID‐19, primarily focused on restructuring clinical training experiences, transforming didactics to online platforms, and maintaining connectedness among leadership, faculty, and staff (Agarwal et al., 2020; Breazzano et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Escalon et al., 2020; Hadley et al., 2020; In et al., 2020; Jotwani et al., 2020; Juprasert et al., 2020; Mallon et al., 2020; Manson et al., 2020; Sagalowsky et al., 2020; Trepal et al., 2020). To date, there have been no reports of the adaptations required within genetic counseling graduate education in response to the pandemic. We set out to explore the multifaceted programmatic changes required from the four institutions in an early pandemic epicenter, providing the longest time horizon available for assessing the implications of this restructuring on graduate education in the profession.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

The practitioners involved all hold positions within the leadership team of one of the four NYC genetic counseling graduate programs, including three program directors, one co‐program director, one associate program director, and two assistant program directors. One co‐program director was invited to participate but declined citing adequate representation of their program on the study team. The mean number of years of experience as a genetic counselor for our group is 16.9 (7–34). Although the majority are relatively new to program leadership roles, with 86% (6/7) having three or fewer years of experience in this role when the pandemic began, collectively we have approximately 90 years of experience working directly with genetic counseling graduate students in some capacity.

2.2. Procedures

We utilized practitioner‐based enquiry (PBE) for this work, a ‘process in which teachers, tutors, lecturers and other education professionals systematically reflect on their own institutional practices’ (Murray, 1992). Practitioner‐centered research techniques have been previously reported in the genetic counseling literature (Lewis et al., 2017; Middleton et al., 2007) and found to generate unique insight.

In October 2020, the program/co‐program directors at our four institutions began meeting weekly by videoconference to collectively reflect on the experience of transitioning our programs in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. We captured each distinct topic that came up in discussion in a shared document and then elaborated in writing between meetings on our individual program experiences. Each week we discussed what had been added to the document the previous week which allowed for further refinement of our reflections and identification of topics not yet discussed. We recognized early in our process that several other individuals within our leadership teams had been intimately involved in the daily operations of the program during this time. In November 2020, three assistant/associate program directors from our programs were invited to join our working group. We continued to meet weekly and our process unfolded for approximately 4.5 total months.

3. RESULTS

Through our iterative reflections, we identified three phases of COVID‐19 response within our programs during this time. For ease, we have labeled them in this manuscript as follows: Phase 1 defined as March 1, 2020 through May 31, 2020, Phase 2 defined as June 1, 2020 through August 31, 2020, and Phase 3 defined as September 1, 2020 through December 31, 2020. These phases roughly correspond with the spring, summer, and fall academic terms at our institutions. Key tasks for each phase are outlined in Table 1 and detailed below.

TABLE 1.

Core actions for each phase

| Key program tasks |

|---|

|

Phase 1: Stabilizing our environments (1 March to 31 May 2020)

|

|

Phase 2: Reinvesting in our programs ( 1 June to 31 August, 2020)

|

|

Phase 3: Planning ahead ( 1 September to 31 December, 2020)

|

Summary of prominent areas of focus during each identified phase of adaptation

3.1. Phase 1 (1 March through 31 May)

3.1.1. Stabilizing our programs in an unstable environment

Our primary goal during this time was to minimize disruption to learning during a time of tremendous stress from multiple sources. In addition to losing routine, structure, safety, in‐person contact, and the NYC lifestyle that is a draw for so many, we grappled with the loss of health and life of loved ones due to COVID‐19. Many in our leadership, faculty, and student cohorts were diagnosed with COVID‐19 or were involved directly with the care of family members diagnosed with COVID‐19. Several experienced the death of close relatives and were unable to travel to be with family due to restrictions. We were immersed in COVID‐19 due to the high rates of infection and hospitalization in NYC. And in May, the long‐standing racial injustice in our country was brought further to light by emerging understandings about the disparities in COVID‐related morbidity and mortality, and by the murder of George Floyd following on the heels of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery. Our city and our nation were in deep pain that reverberated across our virtual campuses and through our faculty, staff, and students.

3.1.2. Didactic coursework

This period was marked by significant reactivity. During the week of March 9, 2020, our programs were given between 24 and 48 hr to transition away from in‐person learning. We scrambled to immediately move planned lectures and classroom‐based learning to video conferencing platforms (Table 2). Considerable programmatic energy was devoted in these first days to familiarizing ourselves with new virtual platforms, assessing technological capabilities of faculty and students, and providing support and guidance for both teaching and learning online. None of our programs had previously used virtual platforms for education, other than an occasional guest speaker providing a lecture remotely, though in these instances our students gathered in person in a classroom to attend. We leaned on colleagues with experience in distributed learning for support, as well as available resources from our libraries and our Centers for Teaching and Learning who were indispensable partners in this transition period. We recorded all classes to assist with student absence, asynchronous learning, and decreased absorption of material. Syllabi were revised to reduce demands on students (e.g., removing some assignments, dropping lowest quiz grades), who we found to be much less cognitively and emotionally available for planned didactic learning. One institution moved to a pass/fail grading structure for the spring term in an effort to address inequities in learning created by both the sudden transition to an online format and the human cost of COVID‐19.

TABLE 2.

Educational technology utilized

| Program Need | Technology Platforma |

|---|---|

| Videoconferencing | Zoom |

| Lecture Recording | Zoom |

| Panopto | |

| Echo360 | |

| Remote Examination | ExamSoft/Examplify |

| LockDown Browser | |

| Blackboard | |

| Program Calendar | Typhon |

| Google calendar | |

| Telehealth Fieldwork and Remote Supervision | EPIC/Haiku/Canto |

| Zoom (HIPAA‐compliant) | |

| BlueJeans (HIPAA‐compliant) | |

| Amwell | |

| Microsoft Teams | |

| Doximity | |

| Jabber | |

| Insight Interpreter Services | |

| Discussion Board | Padlet |

| Jamboard | |

| Tapatalk | |

| Canvas/CourseWorks | |

| Blackboard |

Key educational technology that supported various functions of our programs during the COVID‐19 pandemic

All names and trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

The timing of classes became a concern as students left NYC to live closer to family or friends. NYC was on Eastern Daylight Savings Time (UTC‐04:00) and almost all distributed students were at most three hours behind (UTC‐07:00), so classes were shifted to begin later in the morning. Several international students left the United States and were located in areas that were seven to 12 hr ahead of NYC. These students chose to either stay on NYC time, sleeping during the day and attending classes overnight, or attend classes asynchronously by watching recordings afterward.

Complications arose regarding faculty availability for lectures and course instruction, as some were redeployed to support their hospital systems (Ahimaz et al., 2020), particularly in the programs housed in medical centers, and others were diagnosed with COVID‐19 and unable to teach for a period of time. We benefitted from proactively identifying back‐up faculty with overlapping expertise for as many courses as possible and locating previously recorded relevant lectures available from trusted sources to supplement student learning.

Administration of quizzes and tests was an early challenge faced by our programs, all of which shifted to remote, electronic software platforms (Table 2). While some programs were already providing examinations electronically, this represented a transition for others with a concomitant need to train faculty and students on these tools alongside converting examinations to this format. To address concerns about the security of remote examinations, programs used a combination of reinforcing existing institution‐based honor codes, balancing the window of time available for the examination and the number/type of questions asked, and careful review of performance afterward to identify patterns of correct/incorrect answers. No program instituted remote proctoring for examinations.

3.1.3. Fieldwork

Fieldwork was suspended at all programs by March 13, 2020, and extraordinary creativity was needed to sustain clinical skill building and meet competency benchmarks. As genetic services transitioned to telehealth in mid‐March, a significant number of genetic counselors found themselves in uncharted territory and unable to provide student supervision. Simultaneously, campus simulation centers closed and did not offer remote services during this time. We each created opportunities, including role plays with faculty, role plays with first‐year students from a genetic counseling graduate program outside of NYC, and industry/advocacy observations coupled with online supplemental learning activities.

One of the programs housed within a medical center was able to reestablish their first‐year placements within three weeks via telehealth. Another program canceled all fieldwork during this time, including telehealth opportunities, in deference to high stress within the supervisor network and to maintain equality among experiences for their students. The Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (ACGC) released guidance on April 8, 2020 allowing flexibility for second‐year students to be able to count telehealth and simulated clients toward their required case log, including the allowable use of genetic counselor supervisors as simulated clients (ACGC, 2020). Programs worked extensively with volunteers to prepare them as standardized clients, including the use of shared resources created through a collaboration of genetic counseling graduate programs in North America in April 2020. Across our programs, there was almost no difference in the total number of logbook cases accrued by current second years as compared to the previous 3 cohorts, with the maximum reported difference at any of our programs being 7 less cases accrued on average per student. While none of the second‐year students in our programs were in need of additional cases to meet case log requirements, they were able to continue to accrue cases during this time through a combination of telehealth and program alumni trained as standardized clients. These resources were also used to support ongoing skill development for first‐year students.

3.1.4. Research

Second‐year students were able to complete all research requirements without significant interruption and final presentations were delivered remotely. One program noted that all graduating students submitted an abstract to the National Society of Genetic Counselors annual conference by the May deadline, a similar rate to prior years. Most first‐year student projects continued as planned, though some were changed due to difficulty securing expert mentors who were themselves engaged in the front‐line medical response in NYC or because the planned structure of the project was no longer feasible due to the pandemic. Barriers to planned projects included the inability to randomize between an online and in‐person arm, lack of clinic waiting rooms in which to collect survey data, and incomplete access to data not stored electronically. Student projects were modified as needed to work within these new constraints. One project was revised to include the impact of COVID‐19. Additional support was required from program leadership that oversee student research during this time to ensure that projects were initiated successfully, particularly related to IRB submission, as there was a ramp down of non‐essential research in order to initiate COVID‐related research within our institutions.

3.1.5. Student life

A prominent focus in this phase was promoting social connection to address isolation, maintain cohort integrity, and provide outlets for processing the intense experience of living in a COVID‐19 epicenter. Virtual happy hours, game nights, book clubs, and class meetings were instituted across our programs. One program housed at a medical center had opportunities for students to be involved in supporting the medical response to COVID‐19 at their institution, which was described as a meaningful experience that provided an outlet to counteract feelings of helplessness. The fatigue of consistently being virtual was experienced by both students and faculty and most programs shortened classes held online to 90–120 min with screen breaks in the middle. In exchange, students were asked to have cameras on during class meetings to facilitate interaction, support teaching and learning, and maintain relationships between students and faculty.

Negotiating shared living spaces was also a key component of this time. With the average apartment in NYC being 866ft2 (Talkington & Healy, 2016), bedrooms doubled as workstations and kitchens became offices. Shared Wi‐Fi was frequently strained leading to slowed connections for video conferencing and access to online learning materials. Carving out quiet spaces for meetings and classes proved challenging for many. Accessing outdoor spaces was also difficult, with many being closed to prevent gathering and those that were open often being overly crowded. As well, some students found themselves living with their families of origin, activating family dynamics that seemed to conflict at times with their independence.

3.1.6. Program operations

Indefinite suspension of work‐related travel and hiring freezes beginning in April 2020 was uniform across all programs. One program lost their administrative support from March to October 2020 and responsibilities were absorbed by program leadership. Some budget cuts, experienced primarily by programs housed in medical centers, were offset by fewer programmatic expenses during this time related to social distancing (i.e., no faculty travel to meetings, decreased event expenses), though new expenses were incurred in establishing effective remote workstations for all program leadership and staff at their homes.

3.1.7. Admission and recruitment

The peak of cases in NYC coincided with the submission of rank lists to the Genetic Counseling Admissions Match, causing a great deal of uncertainty about recruitment into the NYC Classes of 2022. One program notified all interviewees as of February 24, 2020 about required symptom attestation and use of hand sanitizer on their campus. Another program did not shake hands at interviews starting March 2, 2020 and by March 4, 2020 was utilizing face coverings when meeting with candidates, which was not a widely accepted practice at the time. One program learned of several cases of student and faculty illness following in‐person interviews and reached back to all relevant applicants to provide notification of potential COVID‐19 exposure. Across our programs, we interviewed 191 applicants in person between February 21 and March 9, 2020 and are not aware of any cases of COVID‐19 transmission as a result.

Our programs had collectively planned for 26 in‐person interview days and approximately one‐third (8/26) were converted to virtual interviews. While transitioning individual interviews to a remote platform was relatively straightforward, programs had differing experiences adapting group activities and time with current students. Several programs offered virtual campus tours using video clips that current students recorded around campus. Many interviewees recognized and expressed appreciation for the efforts made by programs to accommodate the situation, though the transition was disappointing to others, especially those who had already traveled to NYC for their scheduled in‐person interview day(s).

There was initial concern expressed by applicants and admission officers that interviewing remotely and in the midst of the onset of the pandemic might disadvantage people as compared to those who were able to interview in person and/or earlier in the cycle. Applicants also expressed concern that they might not get to assess our programs fully for fit without interviewing in person. However, we found a slightly higher yield from virtual interview days as compared to in‐person days, with 30.0% (78/260) of all applicants interviewing virtually as compared to 31.7% (24/60) of matched applicants.

3.1.8. Graduation and employment

There was no COVID‐related delay in graduation or attrition across the Classes of 2020 during this time. Graduations were held virtually and, although ceremonies felt personal and overall joyful, they were tinged with sadness and disappointment about not being together to say goodbye and a feeling that online graduation was less ceremonial. The majority had secured employment by the time of graduation, though hiring freezes implemented across the country made it difficult to start positions as planned. Hiring freezes impacted the process of identifying employment and two graduates who had secured positions previously lost them in May 2020. For those with job opportunities, decision‐making was complicated by the lack of an in‐person interview, particularly if relocation to an unfamiliar area would be involved. International students wanting to work in the United States experienced additional stressors related to difficulty in obtaining appropriate work visas due to delays related to the COVID‐19 pandemic. The graduates who elected to take the ABGC Certification Examination® (ABGC Exam) in August 2020 fared slightly better than previous years, with 78.4% passing as compared to 73.3% of the Class of 2019 who took the ABGC Examination in August 2019.

3.2. Phase 2 (1 June through 31 August)

3.2.1. Reinvesting in our programs

As we entered June 2020, we were able to take a breath for the first time since the pandemic began. Infection and death rates dropped significantly in NYC (Figure 1), and June 8, 2020 marked the first easing of COVID‐19 social and work restrictions since March 2020. We pivoted time and resources away from mounting a significant medical response to COVID‐19 and invested in forward planning for our programs once again. Students and faculty demonstrated increased resilience as compared to the spring, reframing disappointments as opportunities and promoting more positive perceptions of the pandemic's impact. Though we experienced this phase as less intense than the spring, we were still living under very strict social distancing measures and much of NYC remained locked down.

3.2.2. Didactic coursework

All programs held courses online, though one allowed in‐person attendance by student choice. We were able to plan ahead for a remote summer term which fostered a different approach to course management than in previous months. Leadership and faculty engaged in workshops and ongoing support related to virtual classroom technology and online course design, implementing numerous best practices not possible in the rapid transition of the spring. Summer courses were redesigned as flipped classrooms, with students completing more asynchronous individual work in preparation for synchronous class meetings/discussions. Some programs altered the sequencing of courses in their curriculum to bring more didactic work into the summer, opening additional space for the fall term in the hopes that fieldwork placements would be more plentiful and consistent. Student grades in summer courses were consistent with previous years and course evaluations were largely positive.

3.2.3. Fieldwork

Though reconfigured, sufficient fieldwork opportunities were available for all programs in this phase. Students participated in telehealth sessions and one program had select in‐person experiences available. Based on conversations with students, initial case volume in clinical placements seemed noticeably decreased but appeared to rebound somewhat by the late summer. Significant time and energy were invested during this phase in training and supporting clinical supervisors, the vast majority of whom were new not only to providing telehealth services themselves but also new to remote student supervision. One program held weekly ‘office hours’ for clinical supervisors to share tips and best practices.

On the whole, students and supervisors needed to be much more flexible and creative in their work together, often forming partnerships as they learned telehealth together while still maintaining adequate boundaries to allow supervisors to instruct students in the development of clinical skills. Some aspects of clinical practice were much less accessible to students remotely, including ordering genetic testing (e.g., completion of test requisition forms, involvement in the billing process), interacting with other healthcare providers around informal case discussion, and observing common procedures relevant to the clinical placement. Additionally, issues began to arise related to conducting healthcare appointments in shared living spaces. Not only was sharing of Wi‐Fi and physical space critical, but concerns emerged related to protecting personal health information and other aspects of client confidentiality when providing genetic counseling services. Leadership time was required to work with students, encouraging resolution through increased planning and proactive communication with roommates.

3.2.4. Student life

As pandemic fatigue mounted, wellness offerings became a priority. We worked with our Student Wellness Centers to institute and promote more frequent and diverse offerings, including meditation, mindfulness‐based stress reduction, support groups, and other virtual gatherings aimed at improving quality of life. More frequent individual check‐ins between leadership and students were also utilized. Two programs implemented community pods, in which up to five students not living together could forego social distancing, though continued to require mask use indoors from all students. Cohort relationships were strained occasionally, as several cohabiting students needed to navigate differing levels of risk tolerance related to social distancing and the use of face coverings.

3.2.5. Admission and recruitment

Our primary focus was on retention of the students slated to enroll into the Class of 2022. We began including incoming students in communications and summer activities sooner than typical to create community. Particularly predominant was an effort to connect incoming and current students, which we observed to be reassuring and supportive for the new students, particularly those living outside of NYC. One program engaged their Student Wellness Center to create an online resource for incoming students based on motivational interviewing that supported individualized decision‐making about whether to defer their admission for one year. Although there was some concern that matched applicants might be wary of attending school in an early COVID‐19 pandemic epicenter, across our programs only 3.1% (2/64) of incoming students chose to defer or withdraw their offer of admission and these spots were quickly filled using the unmatched applicant pool from April 2020.

There was uncertainty in the early summer about whether there would be required in‐person components in the fall which would necessitate relocation to NYC. Ultimately, only one program required student attendance on campus for the fall term, though most students from the other three programs chose to relocate to NYC. Housing arrangements were made with relative ease due to less pressure on the overall housing market in NYC during this time. Programs held most orientation events remotely with more sessions being pre‐recorded and watched asynchronously and fewer being held synchronously by videoconference. In‐person orientation events included N95 mask fitting and distribution of personal protective equipment (PPE) at programs housed in medical centers, tours of in‐person clinical spaces on campus, assignment of student IDs, and outdoor socially distanced class socials. Policies related to COVID‐19 and social distancing were reviewed in detail during orientation. Interestingly, several students who relocated from other parts of the United States expressed feeling safer than they had at home due to the almost uniform use of face coverings in NYC and strictly enforced policies in place on campus.

In anticipation of the amount of online learning to be undertaken in the fall term, one program used an online learning module created by their institution that instructs students in best practices for the online learner. This module was viewed by the students asynchronously and then discussed during orientation, with each making a plan for themselves to support their learning. This proactive approach to online learning in advance of the fall term was a change from Phase 1 in which we and our students were only able to react to the shift away from in‐person learning.

3.3. Phase 3 (1 September through 31 December)

3.3.1. Living with COVID‐19

A rhythm developed in this phase that allowed relative predictability in terms of educational delivery, both in didactic coursework and fieldwork. Other than returning to campus, there was very little that we had not done at least once before, which brought relief and opened the door for a sense of normalcy to return. While rates of COVID‐19 were on the rise across the country, including upward trends in some parts of NYC, rates on our campuses remained quite low (<1% positivity rate across all people testing). We settled into new weekly routines and were freed up to consider how we might move ahead sustainably, given that it would likely be at least another year until we had the option to return to a primarily in‐person arrangement for our programs.

3.3.2. Didactic coursework

All programs were hybrid in some format this fall. Of the 38 courses offered between our programs this fall, 58% were held online, 32% in person, and 10% using a HyFlex model (accommodating both in person and remote learners simultaneously). For courses held in person, classroom capacities were recalculated to allow for appropriate social distancing and the use of fabric face coverings was required at all times. Early and frequent interaction with our IT teams enabled abundant support as we continued to rely heavily on these tools to provide high‐quality education. We noticed significantly more ease for both students and faculty, who had better acclimated to the use of technology to support learning, when transitions between in‐person and remote learning were needed. One program implemented team‐based learning groups in order to support students academically. Student grades were again consistent with previous years and course evaluation data were largely positive.

3.3.3. Fieldwork

Student were able to accrue adequate participatory cases during this time. Though there is variation between our programs regarding the specific definition of a participatory case, the average number across the second‐year students in our programs as of December 1, 2020 was 54 which exceeds the total number required by the ACGC at the time of graduation. Some students requested opportunities to ‘make up’ missed cases from spring 2020, though we found on the whole that students’ clinical skills acquisition at this time point did not differ significantly from previous years based on evaluations completed by clinical supervisors.

3.3.4. Student life

Returning to campus was a primary event during this phase. All institutions required COVID‐19 PCR testing before returning to campus, and most continued to test students and faculty at random throughout this phase. Daily symptom attestation was required at all institutions before entering campus buildings. Quarantine protocols were in place and were primarily self‐monitored. One institution created a community compact statement regarding the personal responsibility that each member of the community has to each other, specifically related to commitments to social distancing, forgoing travel and gatherings, and being an active part of the effort to keep the campus safe. All students and faculty were required to sign the compact before returning to campus and it was referenced by leadership throughout the term as needed.

All of us made more frequent referrals to our student mental health services on campus during this period than in years past, regularly encouraging students to take advantage of available support. Approaching holidays from school this term, particularly American Thanksgiving, we proactively engaged students in discussion about travel outside of NYC and gathering indoors to eat with people who are not typically part of their pod. Many students chose to stay in NYC for the holidays and not travel to be with family. One program anonymously surveyed students returning from the fall holiday (25–29 November) and found that more than 25% had hosted or attended indoor events with one or more people with whom they did not normally have contact. This program moved all in‐person courses to a virtual platform for 14 days in response. Another program shifted to being fully remote after the fall holidays for the remainder of the term.

3.3.5. Admission and recruitment

All program‐related recruitment events were held virtually, including open houses, webinars, and career days. Attendance at these events was noticeably higher across all of our programs, and there was a sizeable increase in the number of applications to our programs for the Class of 2023, ranging from approximately 12%–20% more applications than the previous year. As we approached admission for the Class of 2023, all programs planned for virtual interviews. We worked together to share tips and pointers about how best to organize these events based on our experiences from the previous spring and expertise shared by others on our campuses and beyond.

3.3.6. Graduation and employment

The Classes of 2021 were the first ever to experience the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) Annual Conference virtually. Students across our programs were disappointed not to attend in person and were not eager to spend more time online. Numerous concerns about missing out on networking and job opportunities were voiced, and some students reported worry that they did not yet have enough fieldwork experience to talk about as they began interviewing for jobs. Students who participated in virtual networking opportunities found them helpful to varying degrees, with the Minority Genetics Professionals Network discussion thread and the impromptu online student happy hour being the most valuable. One program proactively expanded both content and time within their professional development courses being offered, anticipating that students might need more support this year, including the addition of an inter‐program curriculum vitae and cover letter writing workshop that fostered relationships with students from programs outside of NYC.

Frequent reminders about progress made and how much had been learned were needed, as many students in this cohort seemed to be facing fears of inadequacy. Concerns about the long‐term impact of reduced clinical fieldwork in the spring of 2020 (Phase 1) were common. As well, students shared a sense of feeling unsure about some aspects of engaging with the genetic counseling profession and moving into the workforce, as they did not had nearly as much exposure to working in person in an office/clinic/medical center environment and were not able to attend the NSGC Annual Conference in person.

4. DISCUSSION

We are eager to understand the impact of the countless unanticipated changes in both curricula and operations undertaken in the past year by our four graduate genetic counseling programs in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. We have also begun to consider which of the changes implemented will be more permanent and which will be curtailed as the pandemic resolves. With such a short time horizon and a ground of fairly constant change, we are unable to yet fully assess these changes. However, identifying meaningful outcome measures will be critical to this next phase of evaluation.

4.1. Early outcomes

As we look to traditional indicators of academic and program effectiveness, much seems unchanged at this point. Classes are running, cohorts are full, sufficient clinical cases are being accrued, and graduates are employed. Course evaluations are positive, grades are steady, and ABGC Examination pass rates are similar to prior years. Despite being the first US epicenter in the midst of the prior admission cycle, we experienced no significant negative impacts to recruitment, admission, or retention for any of the cohorts impacted by the pandemic. In fact, attendance of recruitment events offered virtually this fall was noticeably higher across all of our programs and there was a sizeable increase in the number of applications to our programs for the Class of 2023. Attendance at in‐person courses has been excellent and to our knowledge, we have had no instances of COVID‐19 transmission within our classrooms. From this vantage point, things look good.

But when we widen our lens a bit, we see a vastly different landscape than 12 months ago. Faculty and students are emotionally exhausted and fatigued from electronics and ongoing isolation. They report struggling with primarily online education, not having access to their campus buildings and study spaces, and not enjoying in‐person interactions with each other due to the need for social distancing and the use of face coverings. Previous boundaries that supported mental, physical, and emotional health have been dissolved by crisis and new ones have yet to be fully formed. Students who underwent significant disruption to their clinical skills learning through fieldwork seem to require more frequent reassurance than previous cohorts that they are on track. From this perspective, we have much continued work to do.

4.2. Looking ahead

As we prepared to move into the spring 2021 term, COVID‐19 cases continued to rise in NYC and across the United States. As of 31 December 2020, NYC had more cases than during our first peak in April, though the death rates are considerably lower (Figure 1). Several of our students had recently been diagnosed and many others were quarantined, having been exposed to someone who had since tested positive. As we returned to campus for the spring term, we braced for a continued increase in cases and hospitalizations and concomitant social restrictions. We carried with us the potent memories of upheaval caused by significant lockdown measures employed last spring in an attempt to gain control of the rapid spread of the virus.

Simultaneously, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two COVID‐19 vaccines, which our students and faculty began to receive. Our programs offered hybrid learning options in the spring 2021 term, but had readily deployable back‐up plans in place that support a fully remote curriculum. Students and faculty were more acclimated to the technology and rhythm of remote learning. Clinical supervisors had increased dexterity with telehealth and remote supervision. We are more flexible, nimbler, and less complacent than a year ago.

While we hope to revert back to primarily in‐person education across our programs, many of the changes incorporated since March 2020 are here to stay. Telehealth fieldwork and remote supervision will remain a part of our programs, as well as increased use of simulated cases with standardized clients. We anticipate offering more recruitment and admission events virtually rather than requiring travel to our campuses. Educational technology that has become indispensable this past year (Table 2) will continue to support remote meetings with students and program committees, as well as vastly expanding our ability to bring expert guest speakers to our students without requiring travel. These findings are similar to those recently described in graduate medical education (Plancher et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020), perhaps indicating the emergence of new best practices in health profession education more broadly as we move toward the post‐pandemic era and highlighting additional opportunities to engage our students in interprofessional education.

We anticipate continuing with team‐based learning cohorts for students and prioritizing student interaction with faculty and each other during class meeting times. There is also interest in continuing some didactic instruction remotely, though we have learned that articulation of what it takes to be an online learner is important. This represented a significant departure from previous learning styles for many students who were challenged to develop new study habits and time management skills. Creating time for direct student instruction regarding how to be an online learner was both necessary and helpful to support this transition. As students begin to have choice again about participating in programs remotely or in‐person, consideration of their own learning style and the fit with various program models will be important.

We recognize the likelihood of continuing impacts from COVID‐19 to our program operations for the next several years. While salary and hiring freezes and travel restrictions continue, additional suspension/reduction of contributions to pensions and retirement accounts have been recently announced at two of our institutions to ameliorate the significant financial burdens resulting from the intense and unanticipated medical response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. As well, new strains of COVID‐19 are now being detected in NYC which may present continued challenges to our healthcare system. We are likely in the early part of a multi‐year process of adaptation to this novel virus and its global implications, and we look ahead to the continued changes within our field and educational practices as a result of evolutionary pressures being exerted both biologically and socially.

4.3. Limitations

All genetic counseling graduate programs in the United States have likely been required to make at least some adaptations to their curriculum and operations in the wake of the COVID‐19 pandemic and the reflections of our four programs may not be representative of the experience of other programs in our region or across the country. Practitioner‐centered research techniques, such as those used in this study, may bias both the design of the study and the interpretation of the data. There may be salient differences in programs located in less densely populated areas, as well as programs whose class sizes are smaller. As well, our findings likely do not generalize to programs that were already established as virtual/remote prior to the onset of the pandemic, as they may have experienced significantly less disruption of typical operations, as well as benefitted from existing structures and expertise to support remote learning.

4.4. Practice Implications

We have participated for many years in discussion about major change to some of our educational practices within genetic counseling, specifically consideration of integrating more remote learning, increased telehealth education, improved availability of recruitment and admission events that do not require travel, and options for education pathways in addition to the traditional Master's degree. Hesitation has been the mainstay, citing both potential untoward outcomes and the enormity of energy of activation to make substantive change. It is possible that the COVID‐19 pandemic has taught us that our system of graduate education in genetic counseling is more flexible than we know and can accommodate both a volume and intensity of change that we would have previously thought to be unmanageable. Perhaps, the COVID‐19 pandemic will move us in directions that we have needed to go for some time now and encourage us to continue with reduced barriers to innovation.

We anticipate that the pandemic will teach us that clinical competency does not only need to be measured by the number of cases in which we participate as graduate students. While none of us achieve competency without practice, we are very much in need of additional robust and thoughtful measures of clinical competency within our profession for both entry into the field and maintenance of credentials. With a significant minority of the new genetic counseling workforce coming from the NYC area in the next several years, their experiences as students in the midst of an epicenter of the COVID‐19 pandemic will help shape the future of clinical training for years to come.

Our reflective practice during the writing of this manuscript revealed some yet unprocessed thoughts and feelings related to the trauma of the early days of the pandemic on our personal and professional lives. We are grateful that our field prioritizes a self‐reflective approach to practice and strongly encourage all genetic counselors to make space both alone and with peers to explore the multifaceted impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic as we all work to make meaning of this global crisis for ourselves and our profession.

4.5. Research recommendations

Future work is needed to assess educational strategies that have been implemented this past year. Studies related to the use of standardized clients specific to the acquisition of genetic counseling skills are of utmost importance as programs integrate this modality more permanently into their curricula. Establishing best practices and exploring outcomes related to remote student supervision of telehealth encounters is needed, and we are particularly curious about the development and quality of the working alliance between students and supervisors who are fully or mostly remote for clinical placements. Exploring the transition for the classes of 2021 and 2022 into the workforce and longitudinally for the first several years of employment will be instrumental in evaluating the efficacy of programmatic changes, particularly if our workforce returns primarily to office‐based practice. Measures of self‐efficacy and perceived competence in these cohorts would also provide valuable information as adaptations to remote learning continue to be made. We also wish to highlight the need to assess how changes to the recruitment and admission process over the past year, such as offering numerous online options, might influence the future of the profession and perhaps reduce barriers to a more diverse workforce.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We present reflections of four graduate genetic counseling programs in the first US epicenter of the COVID‐19 pandemic and provide early data on the longest timeline available for program evaluation during this time. The curriculum and educational experiences of the students in our collective programs inform a large minority of the new genetic counseling workforce and therefore may help inform how the genetic counseling profession itself will continue to evolve in the aftermath of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

When comparing experiences between our programs, the most significant differences were related to whether a program was housed within an academic medical center. We noted discordance in faculty/student involvement in the medical response to COVID‐19, as well as access to PPE, in‐person curricular experiences, consistent fieldwork, the long‐term financial burdens faced by our institutions, and early access to vaccinations.

Despite these differences, many common elements in our program responses to the COVID‐19 pandemic exist. We found that we and our programs are much more resilient and flexible than we would ever have realized. The level of teamwork demonstrated by program leadership and faculty was phenomenal, finding ways to simultaneously be socially distanced and attached at the hip. Amidst all that was lost, upon reflection, we can identify quite a bit that was gained and look ahead eagerly to retaining the positive aspects of the rapid and numerous shifts needed within our programs to weather this storm. The lessons learned through adapting graduate education so significantly will support our profession through other major life‐shifting events in future, should they arise. Above all, the COVID‐19 pandemic has awakened in us a desire to move ahead with reduced barriers to educational innovation. As we are reminded by Atul Gawande, ‘Better is possible. It does not take genius. It takes diligence. It takes moral clarity. It takes ingenuity. And above all, it takes a willingness to try’ (Gawande, 2007).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Amanda Bergner significantly contributed to the project concept and was a major contributor to study design, drafted the initial version of the manuscript, and acted as the primary revision editor to all version of this manuscript. Lindsey Alico Ecker, Randi Zinberg, and Monika Zak Goelz were major contributors to study design and significantly contributed to paper revisions. Michelle Ernst, Kristina Habermann, and Lisa Karger contributed to study design and significantly contributed to paper revisions. All authors gave final approval of this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of interest

Authors ALB, LAE, MEE, MZG, KH, and LK declare no conflict of interest. REZ is a consultant to Sema4, Inc.

Human studies and informed consent

This study did not meet criteria for review by an institutional and/or national research ethics committee. Because this study utilized practitioner‐centered research, all of the participants were also authors on this study, and their consent was implied in their participation in the gathering of the data and its analysis.

Animal studies

No non‐human animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Data sharing and data accessibility

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The rapid and unprecedented changes required of our graduate programs due to the COVID‐19 pandemic would not have been possible without tireless effort from the entire leadership team at each of our institutions—thank you to Erin Ash, Claire Davis, Chantal Duteau Buck, Laura Hercher, Elana Levinson, Hetanshi Naik, Michelle Primiano, and Janelle Villiers. We are each indebted to our committed faculty, alumni, and colleagues who have awed us with their unending flexibility and patience. Thank you to Jill Gregory for the illustration of Figure 1. We celebrate and acknowledge the rich network of those in our personal lives who make it possible for us to do what we do each day and are deeply grateful for their love and support. We dedicate this manuscript to the students in our programs, whose remarkable resilience during this time will be a defining feature of their professional practice and a continuing inspiration to us all.

Bergner, A. L., Ecker, L. A., Ernst, M. E., Goelz, M. Z., Habermann, K., Karger, L., & Zinberg, R. E. (2021). The evolution of genetic counseling graduate education in New York city during the COVID‐19 pandemic: In the eye of the storm. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 30, 1057–1068. 10.1002/jgc4.1461

REFERENCES

- ACGC . (2020, June 30). Guidance for COVID‐19 related changes. Retrieved 16 October 2020 from https://www.gceducation.org/guidance‐for‐covid‐19‐related‐changes/

- Agarwal, S., Sabadia, S., Abou‐Fayssal, N., Kurzweil, A., Balcer, L. J., & Galetta, S. L. (2020). Training in neurology: Flexibility and adaptability of a neurology training program at the epicenter of COVID‐19. Neurology, 94, e2608–e2614. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahimaz, P., Robinson, S., Hernan, R., & Wynn, J. (2020). Redeployment of genetic counselors in the wake of COVID‐19. NSGC Perspectives, 42, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Breazzano, M. P., Shen, J., Abdelhakim, A. H., Glass, L. R. D., Horowitz, J. D., Xie, S. X., de Moraes, C. G. , Chen‐Plotkin, A., & Chen, C. G., & New York City Residency Program Directors COVID‐19 Research Group . (2020). New York City COVID‐19 resident physician exposure during exponential phase of pandemic. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 130, 4726–4733. 10.1172/JCI139587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. W. S., Abazari, A., Dhar, S., Fredrick, D. R., Friedman, I. B., Dagi Glass, L., Khouri, A. S., Kim, E. T., Laudi, J., Park, S., & Reddy, H. S. (2020). Living with COVID‐19: A perspective from New York area ophthalmology residency program directors at the epicenter of the pandemic. Ophthalmology, 127, e47–e48. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalon, M. X., Raum, G., Tieppo Francio, V., Eubanks, J. E., & Verduzco‐Gutierrez, M. (2020). The immediate impact of the coronavirus pandemic and resulting adaptations in physical medicine and rehabilitation medical education and practice. PM&R, 12, 1015–1023. 10.1002/pmrj.12455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawande, A. (2007). Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance. Metropolitan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, M. B., Lampert, J., & Zhang, C. (2020). Cardiology fellowship during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Lessons from New York City. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 76, 878–882. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In, H., Muscarella, P., Moran‐Atkin, E., Michler, R. E., & Melvin, W. S. (2020). Reflections on the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) epidemic: The first 30 days in one of New York's largest academic departments of surgery. Surgery, 168, 212–214. 10.1016/j.surg.2020.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jotwani, R., Cheung, C. A., Hoyler, M. M., Lin, J. Y., Perlstein, M. D., Rubin, J. E., Chan, J. M., Pryor, K. O., & Brumberger, E. D. (2020). Trial under fire: One New York City anaesthesiology residency programme's redesign for the COVID‐19 surge. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 125, e386–e388. 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juprasert, J. M., Gray, K. D., Moore, M. D., Obeid, L., Peters, A. W., Fehling, D., Fahey, T. J., & Yeo, H. L. (2020). Restructuring of a general surgery residency program in an epicenter of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Lessons from New York City. Journal of the American Medical Association Surgery, 155, 870–875. 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K. L., Erby, L. A. H., Bergner, A. L., Reed, E. K., Johnson, M. R., Adcock, J. Y., & Weaver, M. A. (2017). The dynamics of a genetic counseling peer supervision group. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 26, 532–540. 10.1007/s10897-016-0013-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallon, D., Pohl, J. F., Phatak, U. P., Fernandes, M., Rosen, J. M., Lusman, S. S., Nylund, C. M., Jump, C. S., Solomon, A. B., Srinath, A., Singer, A., Harb, R., Rodriguez‐Baez, N., Van Buren, K. L. W., Koyfman, S., Bhatt, R., Soler‐Rodriguez, D. M., Sivagnanam, M., & Lee, C. K. & NASPGHAN Training Committee COVID‐19 Survey Working Group . (2020). Impact of COVID‐19 on pediatric gastroenterology fellow training in North America. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 71, 6–11. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson, D. K., Shen, S., Lavelle, M. P., Lumish, H. S., Chong, D. H., De Miguel, M. H., Christianer, K., Burnett, E. J., Nickerson, K. G., & Chandra, S. (2020). Reorganizing a medicine residency program in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic in New York. Academic Medicine, 95, 1670–1673. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, A., Wiles, V., Kershaw, A., Everest, S., Downing, S., Burton, H., Robathan, S., & Landy, A. (2007). Reflections on the experience of counseling supervision by a team of genetic counselors from the UK. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 16, 143–155. 10.1007/s10897-006-9074-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L. (1992). What is practitioner based enquiry? Journal of In‐Service Education, 18, 191–196. 10.1080/0305763920180309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plancher, K. D., Shanmugam, J. P., & Petterson, S. C. (2020). The changing face of orthopaedic education: Searching for the new reality after COVID‐19. Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation, 2(4), e295–e298. 10.1016/j.asmr.2020.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagalowsky, S. T., Roskind, C. G., Fein, D. M., Teng, D., & Jamal, N. (2020). Lessons from the frontlines: Pandemic response among New York City pediatric emergency medicine fellowship programs during COVID‐19. Pediatric Emergency Care, 36, 455–458. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S., Diwan, S., Kohan, L., Rosenblum, D., Gharibo, C., Soin, A., Sulindro, A., Nguyen, Q., & Provenzano, D. A. (2020). The technological impact of COVID‐19 on the future of education and health care delivery. Pain Physician, 23(4S), S367–S380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talkington, E., & Healy, C. (2016, September 15). Honey I shrunk the apartments: average new unit size declines 7% since 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2020 from https://www.rclco.com/publication/honey‐i‐shrunk‐the‐apartments‐average‐new‐unit‐size‐declines‐7‐since‐2009/

- Trepal, M. J., Swartz, M. H., & Eckles, R. (2020). Challenges and responses to podiatric medical education and patient care requirements at the New York College of Podiatric Medicine during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery, 59, 884–885. 10.1053/j.jfas.2020.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2021, May 28). WHO coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) dashboard. Retrieved 28 May 2021 from https://covid19.who.int/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.