Abstract

Purpose

Drawing on the self-determination theory and the social role theory, the purpose of this study was to test the moderating role of gender and the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between workplace loneliness and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), and more importantly, the integrated moderated mediation model.

Methods

A total of 290 employees from various Chinese enterprises voluntarily participated in the two-wave surveys. Hierarchical regression and bootstrapping analyses based on Hayes’ Process Model were conducted to test the hypotheses.

Results

Results indicated that work engagement significantly mediates the association of workplace loneliness with OCBs. Gender serves as an important moderator in the relationship among workplace loneliness, work engagement, and OCBs that for female participants the indirect effect of work engagement linking workplace loneliness to OCBs was significant, but for male participants it was not.

Conclusion

This study advances the current understandings of the moderated mediation mechanism among workplace loneliness, gender, work engagement, and OCBs. It is suggested that work engagement serves as a mediator linking workplace loneliness to OCBs, especially for the female employees.

Keywords: workplace loneliness, work engagement, organizational citizenship behaviors, gender difference, moderated mediation

Introduction

The rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic forces many countries into implementing various social distancing strategies, such as “stay-at-home”, which consequently aggravate people’s feeling of loneliness.1,2 In organizational settings, loneliness might be a more serious issue owing to the decreased face-to-face interactions in coping with COVID-193,4 and the increasing competition in the working environment.5,6 It is getting harder for employees to establish and maintain genuine social relationships.5,7 Workplace loneliness, defined as subjective evaluations of insufficient or unsatisfactory social relationship with their colleagues or employers,6,8 has become a serious issue prevalent in organizations,7,9 that has been confirmed to negatively related to employees well-being,10 work engagement,9,11 job performance,7,12 and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs).6 Yet little research has examined the moderated mediation mechanism underlying the effects of employees workplace loneliness on their OCBs.

The self-determination theory (SDT) posits that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are three basic and universal motivations for human beings, and whether these needs are satisfied or not, has a significant influence on individual attitudes and behaviors.13,14 This theory has been widely used to predict the mediating role of attitudes in linking individuals perceptions and behaviors. For example, Karatepe et al11 drew on this theory and hypothesized that work engagement mediated the relationship between employees perceptions of job insecurity and non-green behaviors and absenteeism. Similarly, van Wingerden et al15 confirmed the mediating role of work engagement in the linkage between employees basic need satisfaction and task performance. Given the strong association of workplace loneliness with work engagement9 and OCBs,6 we propose that work engagement should be a linking path relating employees workplace loneliness to their OCBs.

More importantly, the effects of employees workplace loneliness on their attitudes and behaviors may vary across contexts and individuals. Ozcelik and Barsade7 found the culture of companionate love and anger moderate the relationship of employees workplace loneliness with their affective commitment and approachability. In addition, leader-member exchange and coworker exchange buffer the negative effects of workplace loneliness on work engagement and organizational commitment,9 in-role performance, and OCBs.6 Moreover, scholars also confirmed that individual differences, such as future work self salience (which refers to an individual’s representations of himself or herself in the future that reflects his or her hopes and aspirations in relation to work16) and psychological capital, moderate the effects of workplace loneliness on work engagement and OCBs, respectively.16,17

Gender, as a basic demographic variable, has been recognized as a critical moderator in numerous studies on organizational behaviors.18–20 The social role theory maintains that women and men are expected to display distinctive characters because of the influence of their own gender identities and social expectations. Particularly, women tend to be more communal, emotionally and socially oriented, while men are expected to be more assertive, competitive and task oriented.6,21,22 Prior work has confirmed that female employees value interpersonal relationships more than male employees, so that they are more influenced by the poor relations. Cloninger et al19 found that the effect of work family conflict on OCBs was stronger for females than males. Similarly, Huang et al23 revealed a stronger negative effect of loneliness on prosocial behavior for females than males. Considering that women are more vulnerable to the impacts of poor relationships,19,23 we argue that the effects of workplace loneliness on OCB via work engagement may be stronger for women than men.

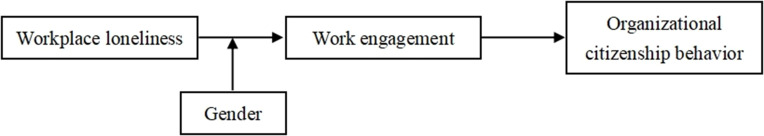

Drawing on the self-determination theory and the social role theory, the goals of this study are to examine the moderating role of gender and the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between workplace loneliness and OCBs, and more importantly, the moderated mediating model. In so doing, this study begins with the review of workplace loneliness, work engagement, OCBs, and gender to propose the moderated mediation model (shown in Figure 1) and hypotheses. Then, these hypotheses are examined with two-wave surveys of employees from various organizations in China. Finally, the theoretical and practical implications of this paper are discussed, and the limitations as well as potential future research directions are described in the last part.

Figure 1.

The moderated-mediating model in this study.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Workplace Loneliness and OCBs

Loneliness has been defined as a subjective and negative experience resulting from a cognitive evaluation of the deficiency in the interpersonal relationship either quantitatively or qualitatively.24 Loneliness in the workplace has been a serious issue prevalent in organizations,7–9 and an increasing number of scholars begin to pay attention to it. Wright et al8 proposed the concept of workplace loneliness and defined it as the subjective and negative experiences occurs when employees affiliation or belonging needs are not being met either quantitatively or qualitatively in the work scenarios. In the Chinese context, Mao25 conceptualized workplace loneliness as interpersonal loneliness and existential loneliness. Interpersonal loneliness is in line with existing definition of workplace loneliness in western context, as qualitive or quantitative unsatisfaction with the interpersonal relationship with others at work.6–8,16 Meanwhile, existential loneliness stands for employees subjective perception of a lack work identity and work value in the organization, which is a distinct dimension of workplace loneliness in the context of Chinese organizations.

OCBs refer to “individuals discretionary or extra-role behaviors aiming to facilitate organizational functioning, which are usually not included in the formal reward system”.26 OCBs usually go beyond the formal requirements of job duties and are self-motivated behaviors. The purpose of individuals’ OCBs is to promote the development of the company they work in, no matter whether these behaviors actually contribute to the organizational functioning or not. It has been confirmed that negative perceptions or evaluations were generally relevant to fewer OCBs.6,17 In particular, Lam and Lau6 found that workplace loneliness decreased Chinese teachers OCBs. Firoz and Chaudhary17 revealed that workplace loneliness was negatively related to Indian employees OCBs.

The self-determination theory (SDT) provides some insights on the negative influence of workplace loneliness on OCBs. When employees needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness were satisfied, they will be more energized, self-motivated and more likely to exert extra time or resource to their work, otherwise, they will be less energized, self-motivated and reduce their time or energy involvement in work.13,14 Applying SDT in the work settings, employees have natural motivation to establish high-quality interpersonal relationships with their colleagues or employers to satisfy their basic needs for relatedness or belonging,13,14,24 and workplace loneliness occurs when employees are unsatisfied with the relational bonds quantitatively or qualitatively with their colleagues or with the enterprise that they work in. As a result, they usually adopt avoidance coping strategies, such as fewer OCBs.27 Given that the negative effect of workplace loneliness on OCBs has been well confirmed by prior works, we conceive no need to hypothesize it in this study.

The Mediating Role of Work Engagement

Based on the self-determination theory, we propose that work engagement may mediate the negative link between workplace loneliness and OCBs. The self-determination theory maintains that employees basic need satisfaction significantly affect their following attitudes and behaviors.28 Work engagement, which has been defined as a positive, fulfilling, work-related motivational-psychological state,29 may serve as an indicator of attitudes in employees evaluation of workplace loneliness and coping behaviors of OCBs. Lonely employees tend to believe that their needs for relatedness are not satisfied in work settings. This negative evaluation will first give rise to negative attitudes towards work, such as low work engagement,9 then results in fewer extra-role duties or OCBs.11,30

Previous studies also proved the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between employees evaluations and coping behaviors. Yalabik et al30 found that work engagement played a mediating role in the impact of affective commitment and job satisfaction on job performance and intention to quit. Similarly, Karatepe et al31 confirmed individual’s sense of job insecurity was negatively relevant to work engagement, which in turn leads to a decrease in non-green and nonattendance behaviors. Therefore, we hypothesize that

Hypothesis 1: Work engagement mediates the link between workplace loneliness and OCBs.

The Moderating Role of Gender

We further propose that the negative influence workplace loneliness exerts on work engagement varies for different gender groups. The social role theory explains how individuals gender identities and social expectations influence their cognitions and behaviors, providing considerable support for the moderating role of gender.21,22,32 It claims that people tend to regulate their behaviors based on their own gender identities and social expectations.22,32 Specifically, positive emotions and self-esteem will rise when there is a good match between their behaviors and self-standards, whereas the mismatches will give rise to negative feelings and decreased engagement. People have the motivation to adjust their behaviors to conform to the cognition of his/her own gender roles. As for social expectations, behaviors in line with social expectations of their gender roles are usually encouraged and rewarded, however behaviors inconsistent with these expectations are often penalized or sanctioned.

The combined influence of employees gender identities and social expectations makes women are more accommodating, communal, socially oriented in workplace settings, while men are usually more agentic, assertive and task oriented.21 As a result, women value interpersonal relationships more than men, so that females are more sensitive to and more influenced by negative affect in the workplace settings.33 Results of an experiment conducted by Geis and Butler33 revealed that female leaders perceived more negative responses and fewer positive responses than male leaders. What is more, women tend to display higher levels of passive destructive and passive constructive behaviors in response to conflicts, including decreasing her time and energy involvement in work.20,34,35

Other studies also indicated that gender plays a moderating role in the relationship between employees negative affect or perceptions and motivations in the workplace settings. In particular, the influence of negative perceptions on motivations seems to be stronger in females than males. For instance, a meta-analysis of Reichl et al35 indicated that women were more influenced by nonwork-to-work and work-to-nonwork conflict, as exhibiting higher level of burnout. Similarly, Mölders et al18 inferred that gender moderated the negative bonds between employees’ perception of trustworthiness and their negative emotions, that it was stronger for females than males. Therefore, we predict that

Hypothesis 2: Gender moderates the direct effect of workplace loneliness on work engagement, such that the influence of workplace loneliness on work engagement would be stronger for female employees than male employees.

The Moderated Mediating Model

We argue that there should be a moderated mediation model in which the influence of the mediator (work engagement) in linking workplace loneliness and OCBs varies because of different gender. Specifically, for females, the negative effect of workplace loneliness on work engagement is augmented, which strengthening the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between workplace loneliness and OCBs. Meanwhile, for males, the impact of workplace loneliness on work engagement is weakened, which neutralizing the role of work engagement in mediating the association of workplace loneliness with OCBs. Therefore, we propose that

Hypothesis 3: Gender moderates the mediating effect of work engagement in the relationship between workplace loneliness and OCBs such that the mediating role of work engagement would be stronger for female employees than male employees.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

A total of 339 employees voluntarily participated in the two-wave surveys via either paper-and-pencil survey or Tencent Questionnaire website. In the first wave of surveys, employees reported their workplace loneliness and demographic information. One month later, questionnaires for measuring work engagement and OCBs were administered to the employees who completed the first survey. The final sample pool contained 290 (85.5%) valid paired responses. Among them, 64.8% were female and 35.2% were male with an average age of 28 (SD = 7.05) and an average of 6.37 (SD = 22.73) years of organizational tenure. 70.0% of the participants had a bachelor degree and 41.4% occupied managerial positions.30.0% worked in state-owned enterprises, 39.3% worked in private-owned enterprises and 30.7% worked in foreign-owned enterprises or other organizations. 21.7% and 20.3% of the participants were in the high-tech or the traditional industries, respectively. 10.3% were in the financial industry and 47.7% were in other industries.

Measures

We used 5-point Likert-type scales ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) for all substantive variables. We employed translation and back-translation procedures36 to translate all English items into Chinese.

Workplace Loneliness

We measured workplace loneliness using the ten-item scale of Mao,25 which was adapted from the original scale of Wright et al8 to match the Chinese context. It contains two subscales: interpersonal loneliness and existential loneliness, and each consists of five items. Sample items are “I always cannot find colleagues to talk to when encountered with difficulties or problems at work”; “I feel that I have not been recognized and valued by colleagues and leaders in the company”. This scale is reliable and widely used in the Chinese context, with a Cronbach’s alpha from 0.89 to 0.95.16,25,37–39 The Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.93.

Work Engagement

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale developed by Schaufeli et al29 was used. It includes three subscales: dedication, vigor, and absorption, and each contains 3 items. Sample items are “At my work, I feel bursting with energy,” and “My job inspires me”. The Cronbach’s α was 0.95.

OCBs

The 16-item OCBs scale developed by Lee and Allen27 was used. It has two dimensions: OCBs directed at individuals and OCBs directed at the organization, each has 8 items. Sample items are “Willingly give your time and energy to help others who have work-related problems,” and “Keep up with developments in the organization”. The Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.93.

Gender

We asked the participants to indicate their gender (0 = male, 1= female).

Control Variables

We included individuals demographic information such as age, tenure, education level and position in the organization as control variables. The education level was measured by five categories (1 = middle school or below, 2 = high school, 3 = college, 4 = university, and 5 = postgraduate); position in the organization as four types (1 = employees, 2 = junior manager, 3 = middle manager, and 4 = senior manager).

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA)

Before testing the hypotheses, a series of CFA was conducted to evaluate the discriminant validity among the study variables. Seven factors were included: two dimensions of workplace loneliness (interpersonal loneliness and existential loneliness), three dimensions of work engagement (dedication, vigor, and absorption), as well as two dimensions of OCBs (OCBs directed at individuals and OCBs directed at the organization). We compared the goodness of baseline seven-factor model fit to five alternative models using the data collected from two-wave surveys. Results in Table 1 indicated that model 1 fit the data well (χ2/df = 2.35, RMSEA = 0.068, IFI = 0.913, TLI = 0.903, CFI = 0.912) and provided substantial improvement in fit indices over models 2–6.

Table 1.

Comparison of Alternative Measurement Models

| Models | Factors | χ2/df | Δχ2 | RMSEA | IFI | TLI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seven factors: EL, LL, DD, VG, AB, OI, OO | 2.35 | 0.068 | 0.913 | 0.903 | 0.912 | |

| 2 | Six factors: EL+LL, DD, VG, AB, OI, OO | 2.83 | 277.26** | 0.080 | 0.880 | 0.868 | 0.879 |

| 3 | Five factors: EL+LL, DD, VG, AB, OI + OO | 3.84 | 846.70** | 0.099 | 0.812 | 0.795 | 0.811 |

| 4 | Three factors: EL+LL, DD+VG+AB, OI+OO | 4.15 | 1045.27** | 0.104 | 788 | 0.773 | 0.787 |

| 5 | Two factors: EL+LL, DD+VG+AB+OI+OO | 5.21 | 1648.33** | 0.121 | 0.716 | 0.696 | 0.714 |

| 6 | One factor: EL+LL+DD+VG+AB+OI+OO | 7.80 | 3100.97** | 0.153 | 0.540 | 0.509 | 0.538 |

Note: **p < 0.01.

Abbreviations: EL, existential loneliness; IL, interpersonal loneliness; DD, dedication; VG, vigor; AB, absorption; OI, OCB directed at individuals; OO, OCB directed at organization.

Hypotheses Testing

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables. The results show that workplace loneliness was negatively related to work engagement (r = −0.365, p < 0.01) and OCBs (r = −0.312, p < 0.01). Moreover, work engagement was positively associated with OCBs (r = 0.697, p < 0.01). We then conducted hierarchical regressions and bootstrapping analyses40 to examine the hypotheses. Table 3 shows the results of hierarchical regressions.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, Correlations of All Variables

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender | 1.65 | 0.48 | |||||||

| 2 | Age | 28.99 | 7.05 | −0.295** | ||||||

| 3 | Tenure | 6.37 | 22.73 | −0.145* | 0.449** | |||||

| 4 | Education | 3.90 | 0.67 | −0.063 | 0.056 | −0.095 | ||||

| 5 | Position | 1.57 | 0.79 | −0.355** | 0.459** | 0.126* | 0.274** | |||

| 6 | Workplace loneliness | 2.27 | 0.94 | 0.025 | 0.026 | 0.201** | −0.221** | −0.142* | ||

| 7 | Work engagement | 3.65 | 1.21 | −0.246** | 0.254** | 0.154** | 0.158** | 0.300** | −0.365** | |

| 8 | OCBs | 4.17 | 0.89 | −0.151** | 0.229** | 0.109 | 0.122* | 0.249** | −0.312** | 0.697** |

Notes: N = 290; **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Results of Hierarchical Regressions

| Variable | Work Engagement | OCBs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Age | 0.25* | 0.20* | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.07 | −0.06 |

| Tenure | −0.11 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.15* |

| Education | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Position | 0.20** | 0.16** | 0.13* | 0.16* | 0.13* | 0.02 |

| Workplace loneliness | −0.33** | −0.16 | −0.31** | −0.09 | ||

| Gender | −0.15** | |||||

| Gender * Workplace loneliness | −0.23** | |||||

| Work engagement | 0.65** | |||||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.50 |

| ΔR2 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.33 |

| ΔF | 9.65** | 37.24** | 7.44** | 6.74** | 29.38** | 188.47** |

Notes: N = 290; **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Hypothesis 1 predicted the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between workplace loneliness and OCBs, we followed Baron and Kenny’s41 procedure and found a negative effect of workplace loneliness on work engagement (r = −0.33, p < 0.01) and OCBs (r = −0.31, p < 0.01). More importantly, the relationship between workplace loneliness and OCBs became not significant (r = −0.09, n.s.) when work engagement entered the model.

To further confirm the mediating role of work engagement, we conducted bootstrapping analyses using PROCESS.40 The results showed that the bias-corrected CIs with 10,000 bootstrapped samples of the indirect effect of work engagement linking workplace loneliness to OCBs (indirect effect = −0.217, SE = 0.039, BC 95% CI = [−0.296, −0.144]) did not include zero, providing support for Hypothesis 1.

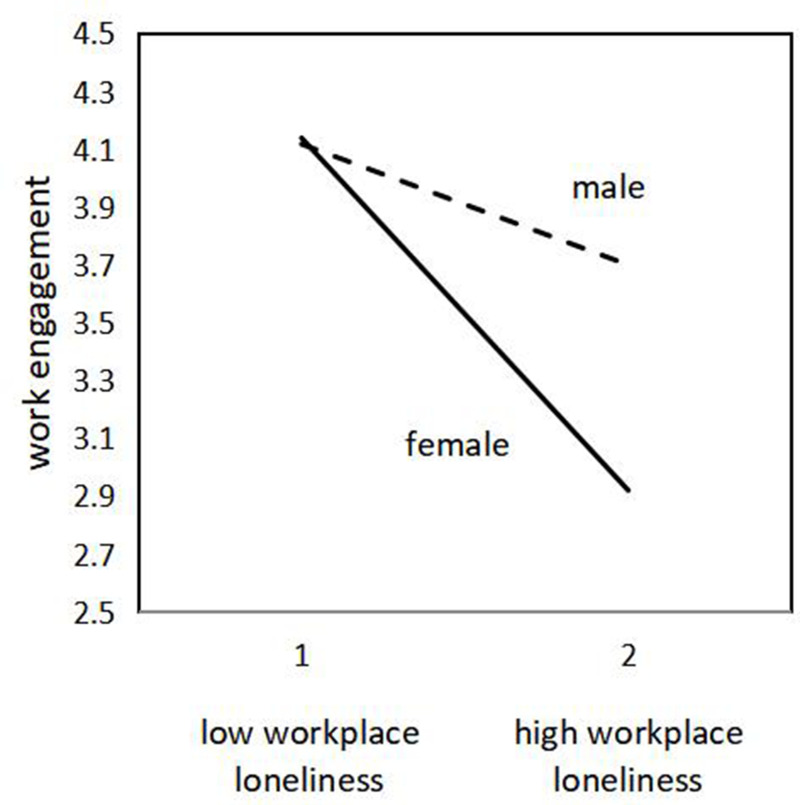

Hypothesis 2 predicted the moderating role of gender in the relationship between workplace loneliness and work engagement. The results in Table 3 indicates that the interaction of workplace loneliness and gender was negatively related to work engagement (r= −0.23, p < 0.01). We followed Aiken et al42 to explicate the interaction, as shown in Figure 2. It can be seen that for female participants, workplace loneliness was negatively associated with work engagement (r = −0.580, p < 0.01); but for male participants, it was not (r = −0.199, p = 0.069, n.s.). These results provide considerable support for Hypothesis 2.

Figure 2.

The interactive effect of workplace loneliness and gender on work engagement.

To examine Hypothesis 3 that predicted the moderated mediating model, we employed bootstrapping analyses using PROCESS.40 The results in Table 4 revealed a significant moderated mediation effect (the contrast = −0.184, SE = 0.069, BC 95% CI = [−0.317, −0.042]) did not include zero. In particular, for female participants the indirect effect of work engagement linking workplace loneliness and OCBs was significant (indirect effect = −0.280, SE = 0.045, BC 95% CI = [−0.369, −0.192], did not include zero); but for male participants the indirect effect was not significant (indirect effect =−0.096, SE = 0.057, BC 95% CI = [−0.217, 0.009], included zero). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Table 4.

Results of Moderated Mediating Effect

| Variable | Effect | Standard Error | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Limit | Lower Limit | |||

| Male | −0.096 | 0.057 | −0.217 | 0.009 |

| Female | −0.280 | 0.045 | −0.369 | −0.192 |

| Difference | −0.184 | 0.069 | −0.317 | −0.042 |

Discussion

Prior work has repeatedly confirmed that workplace loneliness is harmful to individuals and organizations, owing to its influence on poor mental health,4 lower work engagement,9,16 lower job performance,6,7,12 higher turnover intention43 and fewer OCBs.6 However, few studies have concentrated on the mediating and moderating factors in the effects of workplace loneliness. Drawing on the self-determination theory13,14 and the social role theory,21 we proposed and empirically examined a moderated mediation model in which the indirect effect of workplace loneliness on OCBs via work engagement varies for female employees and male employees. In particular, we found that although both men and women tend to decrease their OCBs as a response to workplace loneliness through decreased work engagement, the negative effect of workplace loneliness for women was stronger than men.

Theoretical Contributions

The findings of this study make several theoretical contributions to the literature of workplace loneliness and its consequences. First, the results revealed a full mediation of work engagement in the negative effects of workplace loneliness on OCBs. It is in accordance with the prior work that drew on the self-determination theory to examine the mediating role of employees psychological state (thriving at work) in linking need for relatedness satisfaction indicator (leader inclusiveness) to employees behaviors (taking charge behavior).28 In this study, when employees perceived a lack of interpersonal relationship quantitatively or qualitatively, they would reduce their time or energy involvement in work, thus decrease their OCBs. It is also consistent with other existing empirical studies in which work engagement serves as a mediator between employee perceptions and behaviors.30,31

Second, we found a solid evidence of gender differences in the negative influence of workplace loneliness on work engagement was also confirmed, such that this negative effect was stronger for females than for males. Inferring from the social role theory,21 women are more accommodating, communal, socially oriented, while men are expected to be more agentic, assertive and task oriented, because of the effect of their gender identities and social expectations, such that females tend to employ more avoidance emotional or behavioral coping strategies when confronted with stresses or other negative events at work. In this study, both females and males are negatively influenced by workplace loneliness, while females are more effected than males, experiencing a lower level of work engagement when their needs for relationship or belongings are not satisfied in the workplace settings.

Third and more importantly, this study identified a moderated mediation model in which gender moderates the indirect effect of work engagement in the relationship between workplace loneliness and OCBs. In particular, the negative effect of workplace loneliness on OCBs through work engagement was stronger for female employees than male employees. In other words, females are more likely to reduce their work engagement and then OCBs as a response to workplace loneliness. This study is among the first to spot light on the moderated mediation model of employees reaction to workplace loneliness, which advances the current understandings of gender differences in a series of attitudinal and behavioral responses to workplace loneliness in organizational settings.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study indicate that workplace loneliness actually imposes a negative influence on employees and organizations, as it contributes to lower work engagement and then fewer OCBs. Owing to the fierce competition and constantly changing environment, organizations more and more depend on employees positive attitudes like work engagement and proactive behaviors like OCBs to sustain and maintain its competitive advantage. More attention should be paid to satisfy employees needs for interpersonal relationships or belongings, such as organizing more league building activities to strengthen the interpersonal relationships among employees, setting up a psychological consultation room to help them release their negative perceptions or stresses at work, in order to increase their work engagement and trigger their OCBs.

Moreover, the results in this study demonstrate that females and males respond differently to workplace loneliness such that the negative consequences of workplace loneliness are more prevalent for female employees. Therefore, managers and organizations should be aware of this gender difference and consider it in managerial practices. In so doing, more attention should be paid to relieve females perceptions of loneliness in the workplace given its stronger negative impacts on work engagement and OCBs.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study also has some limitations that need to be further explored in future research. First, although this study employed two-wave surveys and the result of CFA indicated good discrimination validity among workplace loneliness, work engagement, and OCBs, common method variance remains a limitation in this study owing to the same source of the data. In particular, employees may underestimate workplace loneliness, overestimate work engagement, and report more OCBs, because of social approval effect or self-impression management. Future studies are recommended to extend the data source, inviting leaders to evaluate employees OCBs, or collecting objective external-role performance data, to decrease the detrimental influence of common method variance.

Second, we only explored the mediating role of work engagement and the moderating role of gender in the relationship between workplace loneliness and OCBs. It has been revealed that workplace loneliness was also related to job performance,6,7 creativity,5 organizational commitment,10 and intention to quit.44,45 Future works are encouraged to further examine the mediating and the moderating factors in the effects of workplace loneliness on other attitudes and behaviors.

Conclusions

The present study advances the current understandings of the moderated mediation mechanism among workplace loneliness, gender, work engagement, and OCBs. It is suggested that work engagement serves as a mediator linking workplace loneliness to OCBs, especially for the female employees. In particular, the findings suggest that work engagement fully mediates the negative effect of workplace loneliness on OCBs and this influencing path would be stronger for female employees than male employees.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No.: 71902123), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Project No.: 2018M643513), Innovation Spark Project of Sichuan University (2018hf-46); Central University Basic Research Project (LH2018012).

Funding Statement

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No.: 71902123), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Project No.: 2018M643513), Innovation Spark Project of Sichuan University (2018hf-46); Central University Basic Research Project (LH2018012); and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project No.: skbsh2019-39).

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the Ethic Committee on Human Experimentation of Sichuan University and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. In the first-wave questionnaire, we introduced the study purposes and explained that this study welcomed voluntary participation and the data, complying with the principle of confidentiality, is only used for research purposes. Before responses to the questionnaire, all participants filled in a written informed consent form, claimed their understanding of the study purposes and they would like to participate in the study voluntarily.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Rumas R, Shamblaw AL, Jagtap S, Best MW. Predictors and consequences of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiat Res. 2021;300:113934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luchetti M, Lee JH, Aschwanden D, et al. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. Am Psychol. 2020;75(7):897–908. doi: 10.1037/amp0000690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mäkiniemi J, Oksanen A, Mäkikangas A. Loneliness and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: the moderating roles of personal, social and organizational resources on perceived stress and exhaustion among Finnish university employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):7146. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18137146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotera Y, Ozaki A, Miyatake H, et al. Mental health of medical workers in Japan during COVID-19: relationships with loneliness, hope and self-compassion. Curr Psychol. 2021:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01514-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng J, Chen Y, Xia Y, Ran Y. Workplace loneliness, leader-member exchange and creativity: the cross-level moderating role of leader compassion. Pers Indiv Differ. 2017;104:510–515. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam LW, Lau DC. Feeling lonely at work: investigating the consequences of unsatisfactory workplace relationships. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2012;23(20):4265–4282. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.665070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozcelik H, Barsade SG. No employee an island: workplace loneliness and job performance. Acad Manage J. 2018;61(6):2343–2366. doi: 10.5465/amj.2015.1066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright SL, Burt CDB, Strongman KT. Loneliness in the workplace: construct definition and scale development. N Z J Psychol. 2006;35(2):59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung HS, Song MK, Yoon HH. The effects of workplace loneliness on work engagement and organizational commitment: moderating roles of leader-member exchange and coworker exchange. Sustainability. 2021;13(2):948. doi: 10.3390/su13020948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayazlar G, Güzel B. The effect of loneliness in the workplace on organizational commitment. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;131:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karatepe OM, Yavas U, Babakus E, Deitz GD. The effects of organizational and personal resources on stress, engagement, and job outcomes. Int J Hosp Manag. 2018;74:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amarat M, Akbolat M, Ünal Ö, Güneş Karakaya B. The mediating role of work alienation in the effect of workplace loneliness on nurses’ performance. J Nurs Manage. 2018;27(3):553–559. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Wingerden J, Derks D, Bakker AB. Facilitating interns’ performance: the role of job resources, basic need satisfaction and work engagement. Career Dev Int. 2018;23(4):382–396. doi: 10.1108/CDI-12-2017-0237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Lin X, Xi Y. How will the lonely employee be more engaged in: research on the moderation effect of future work self salience and transformational leadership. Nankai Bus Rev. 2019;5(22):79–89. in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Firoz M, Chaudhary R. The impact of workplace loneliness on employee outcomes: what role does psychological capital play? Pers Rev. 2021;ahead-of-print. doi: 10.1108/PR-03-2020-0200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mölders S, Brosi P, Spörrle M, Welpe IM. The effect of top management trustworthiness on turnover intentions via negative emotions: the moderating role of gender. J Bus Ethics. 2019;156(4):957–969. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3600-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cloninger PA, Selvarajan TTR, Singh B, Huang SC. The mediating influence of work-family conflict and the moderating influence of gender on employee outcomes. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2015;26(18):2269–2287. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2015.1004101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis MH, Capobianco S, Kraus LA. Gender differences in responding to conflict in the workplace: evidence from a large sample of working adults. Sex Roles. 2010;63(7–8):500–514. doi: 10.1007/S11199-010-9828-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eagly AH. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eagly AH, Wood W. Social role theory. In: Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2012:458–476. doi: 10.4135/9781446249222.n49 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang H, Liu Y, Liu X. Does loneliness necessarily lead to a decrease in prosocial behavior? The roles of gender and situation. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1388. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perlman D, Peplau LA. Theoretical approaches to loneliness. In: Gilmour R, Duck S, editors. Personal Relationship in Disorder. London, UK: Academic Press; 1981:31–56. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao C. The Development of Workplace Loneliness Scale and Study on its Influencing Factors [master dissertation]. Guangdong, China: South China Normal University; 2013. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Organ DW. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexington Books: Washington, DC, USA; DC Health and Company. Lexington MA, USA; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee K, Allen NJ. Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: the role of affect and cognitions. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(1):131–142. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li N, Guo Q, Wan H. Leader inclusiveness and taking charge: the role of thriving at work and regulatory focus. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2393. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-romá V, Bakker AB. The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3(1):71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yalabik ZY, Popaitoon P, Chowne JA, Rayton BA. Work engagement as a mediator between employee attitudes and outcomes. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2013;24(14):2799–2823. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.763844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karatepe OM, Rezapouraghdam H, Hassannia R. Job insecurity, work engagement and their effects on hotel employees’ non-green and nonattendance behaviors. Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;87:102472. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood W, Early AH. Gender. In: Fiske ST, Gilbert DT, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. 5th ed. Hoboken, USA: John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2010:629–667. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geis D, Butler RW. Nonverbal affect responses to male and female leaders: implications for leadership evaluations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;1(50):48–59. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matud MP. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Pers Indiv Differ. 2004;37(7):1401–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichl C, Leiter MP, Spinath FM. Work–nonwork conflict and burnout: a meta-analysis. Hum Relat. 2014;67(8):979–1005. doi: 10.1177/0018726713509857 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instrument. In: Lonner WJ, Berry JW, editors. Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. Beverly Hills, CA, USA: Sage; 1986:137–164. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J. The Relationship between Employees’ Workplace Loneliness and Work Performance: The Mediating Role of Organization Commitment [master dissertation]. Jilin, China: Jilin University; 2017. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang S. The Internal Mechanism of Workplace Loneliness Affecting Employee Creativity [master dissertation]. Shanxi, China: Northwest University; 2019. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu D. A Study on the Relationship among the Congruence in Organization Support, Workplace Loneliness and Turnover Intention of the New Generation Employee [Master dissertation]. Jilin, China: Jilin University; 2018. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sauzend Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen X, Peng J, Lei X, Zou Y. Leave or stay with a lonely leader? An investigation into whether, why, and when leader workplace loneliness increases team turnover intentions. Asian Bus Manag. 2021;20(2):280–303. doi: 10.1057/s41291-019-00082-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, Wen Z, Peng J, Liu X. Leader-follower congruence in loneliness, LMX and turnover intention. J Manage Psychol. 2016;31(4):864–879. doi: 10.1108/JMP-06-2015-0205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ertosun ÖG, Erdil O. The effects of loneliness on employees’ commitment and intention to leave. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;41:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.04.057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]