Key Points

Question

What is the impact of the acuity circles (AC) allocation policy on the cost of liver acquisition?

Findings

In this single-center study including 213 donors, the mean total costs of liver acquisition increased 16% per accepted donor and 55% per declined donor, with a greater than 2-fold increase in donors incurring import fees and surgeon fees after the implementation of AC allocation.

Meaning

There is urgent need to address the increasing costs of liver acquisition to maintain transplant center financial viability and prevent geographic disparities in access to organs based on these costs.

This single-center study evaluates whether the costs associated with liver acquisition changed after the implementation of acuity circles allocation.

Abstract

Importance

Acuity circles (AC) liver allocation policy was implemented to eliminate donor service area geographic boundaries from liver allocation and to decrease variability in median Model of End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score at transplant and wait list mortality. However, the broader sharing of organs was also associated with more flights for organ procurements and higher costs associated with the increase in flights.

Objective

To determine whether the costs associated with liver acquisition changed after the implementation of AC allocation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This single-center cost comparison study analyzed fees associated with organ acquisition before and after AC allocation implementation. The cost data were collected from a single transplant institute with 2 liver transplant centers, located 30 miles apart, in different donation service areas. Cost, recipient, and transportation data for all cases that included fees associated with liver acquisition from July 1, 2019, to October 31, 2020, were collected.

Exposures

Primary liver offer acceptance with associated organ procurement organization or charter flight fees.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Specific fees (organ acquisition, surgeon, import, and charter flight fees) and total fees per donor were collected for all accepted liver donors with at least 1 associated fee during the study period.

Results

Of 213 included donors, 171 were used for transplant; 90 of 171 (52.6%) were male, and the median (interquartile range) age of donors was 41.0 (30.0-52.8) years in the pre-AC period and 36.9 (24.0-48.8) years in the post-AC period. There was no significant difference in the post-AC compared with pre-AC period in median (range) MELD score (24 [8-40] vs 25 [6-40]; P = .27) or median (range) match run sequence (15 [1-3951] vs 10 [1-1138]; P = .31), nor in mean (SD) distance traveled (155.83 [157.00] vs 140.54 [144.33] nautical miles; P = .32) or percentage of donors requiring flights (58.5% [69 of 118] vs 56.8% [54 of 95]; P = .82). However, costs increased significantly in the post-AC period: total cost increased 16% per accepted donor (mean [SD] of $52 966 [13 278] vs $45 725 [9300]; P < .001) and 55% per declined donor (mean [SD] of $15 865 [3942] vs $10 217 [4853]; P < .001). Contributing factors included more than 2-fold increases in the proportions of donors incurring import fees (31.4% [37 of 118] vs 12.6% [12 of 95]; P = .002) and surgeon fees (19.5% [23 of 118] vs 9.5% [9 of 95]; P = .05), increased acquisition fees (10% increase; mean [SD] of $43 860 [3266] vs $39 980 [2236]; P < .001), and increased flight expenses (43% increase; mean [SD] of $12 904 [6066] vs $9049 [5140]; P = .002).

Conclusions and Relevance

The unintended consequences of implementing broader sharing without addressing organ acquisition fees to account for increased importation between organ procurement organizations must be remedied to contain costs and ensure viability of transplant programs.

Introduction

On February 4, 2020, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) implemented a new liver and intestinal organ allocation policy called the acuity circles (AC) framework. The primary concern driving policy change was that the prior allocation framework, Share 35, used donor service areas (DSAs) and regional boundaries for organ allocation, creating geographic disparities in liver transplant.1 Prior to this change, modeling of potential replacement allocation frameworks assessed key metrics, including median Model of End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score at transplant, number of transplants performed, wait list mortality, posttransplant mortality, transportation time, and percentage of organs flown.1 Considerations in choosing the AC framework included decreased geographic variance of median (range) MELD score at transplant (from 9.97 [8.74-11.90] to 4.33 [3.23-6.27]) and wait list mortality (by approximately 114 deaths per year). The drawbacks were an increase in organ travel time (approximately 12 minutes), percentage of organs flown (from 54.1% to 71.4%), and a manageable increase in costs associated with flight fees.1,2 Contrary to predictions, early analysis found that there were similar differences in both DSA and center-level variance of median MELD score at transplant after AC allocation.3 However, as predicted, the percentage of procurements with a flight-consistent distance substantially increased, and 90 of 112 liver transplant centers in the US saw an increase in the number of flight-consistent distance procurements, suggesting that most centers have also experienced an increase in the transportation costs associated with liver acquisition.

For a comprehensive cost analysis of organ acquisition, fees beyond those associated with transportation need to be studied. The 4 primary fees associated with a liver procurement are organ acquisition fees, import fees, surgeon fees, and charter flight fees (eFigure in the Supplement). Organ acquisition fees are the fees charged by the donor organ procurement organization (OPO) for an organ that is used for transplant. Each OPO sets its own organ acquisition fee, which can include any of the following expenses: costs of organs acquired from other surgeons, costs of transportation, surgeon fees, tissue typing, preservation and perfusion costs, and care services and operating room costs.4 Export surcharges are added to organ acquisition fees for organs that are accepted by a transplant center outside of the donor hospital DSA boundary. Import fees are the charges from the recipient/importing OPO for services related to the import of the organ, which can include transportation coordination, surgical coordinator services, preservation fluids, and invoice processing. Each OPO sets a single import fee that is charged regardless of the service(s) provided when the OPO is involved with a donor from outside of their DSA, and import fee charges are at the discretion of OPOs, so some may not charge them at all. Surgeon fees are charged by the recipient/importing OPO when the donor/exporting OPO does not reimburse the procurement surgeon using funds from the organ acquisition fee. Surgeon fees are not dependent on the affiliation of the procurement surgeon, meaning they are charged based on whether the organ acquisition fee covers the surgeon fee, not on whether the surgeon is associated with the recipient transplant center. Charter flight fees are the charges to the importing center for charter flight transportation.

Analyses of the Share 35 liver allocation framework found that the increased proportion of donor organs imported and exported between DSAs contributes substantially to increased OPO costs, either through increasing the number of organs appearing on the OPO cost report5 or through the import/export fee surcharges, but to our knowledge, the financial impact on transplant centers was never studied.6 Given that that AC allocation increased the number of flight-consistent distance procurements, we hypothesized that the AC policy change would also correspond to increased liver acquisition costs. To test this hypothesis, we compared single-center liver acquisition costs before and after the implementation of the AC allocation policy.

Methods

Data Collection

All liver donors with associated OPO and flight invoice data from July 1, 2019, to October 30, 2020, were collected from a prospectively maintained research database, divided into the pre-AC period (July 1, 2019, to February 3, 2020) and post-AC period (February 4, 2020, to October 30, 2020). We chose a longer post-AC time frame (7 months pre-AC vs 9 months post-AC) to account for the significant national decline in deceased donor organs from February to March 2020 associated with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.7 Donor, recipient, and transportation data were obtained from UNOS. Local procurements were defined as donor procurements within the recipient hospital DSA, and import/export procurements were defined as donor procurements outside of the recipient hospital DSA, regardless of transportation method. All data were recorded in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) version 10.6.12 (Vanderbilt University).8,9 This study was reviewed and approved by the Baylor University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. As the study entails retrospective review of cost data/events that have already occurred and has no influence on patient management, the institutional review board granted a waiver of consent.

Fee Types

The fee types collected from OPO and flight invoices included organ acquisition fees, import fees, surgeon fees, and charter flight fees. One invoice included a fly-out fee, which was charged by the donor OPO for surgical coordinator services for a local (within DSA) fly-out donor.

Center Description and Practices

The Baylor Simmons Transplant Institute (BSTI) has 2 liver transplant centers, C1 and C2, located 30 miles apart and in different DSAs. In the pre-AC period, patients were transplanted at the center that received the organ offer. In the post-AC period, since most patients would appear on the match run sequentially, when given the choice, patients were transplanted at the center where they were evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

Donor and recipient characteristics and fees associated with organ acquisition were compared between those in the pre-AC and post-AC groups. Categorical data were compared using Fisher exact or χ2 test. Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests were used for comparison of continuous data with categorical data. All statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.0.1 (The R Foundation). All P values were 2-tailed, and statistical significance was set at a P value less than .05.

Results

Donor and Recipient Characteristics

We identified 213 donors with associated fees, with 95 donors in the pre-AC group and 118 in the post-AC group. Of 213 included donors, demographic data were available for 171 that were used for transplant. In the pre-AC period, 44 of 82 donors (53.7%) were male, and the median (interquartile range) age was 41.0 (30.0-52.8). In the post-AC period, 46 of 89 (51.7%) were male, and the median (interquartile range) age was 36.9 (24.0-48.8) years. A total of 11 donors did not have complete cost data and were excluded from the cost analysis but included in the descriptive analysis of donors and recipients. Table 1 shows donor and recipient characteristics pre-AC vs post-AC allocation. In the post-AC period, a higher percentage of donation after circulatory death livers were accepted (46.6% [55 of 118] vs 29.5% [28 of 95]; P = .02) and transplanted (38.0% [35 of 92] vs 19.8% [16 of 81]; P = .01). The transplant rate of donors with associated fees, defined as the percentage of livers transplanted divided by all accepted donors with associated fees, did not change in the post-AC period (78.0% [92 of 118] vs 85.3% [81 of 95]; P = .24). In the post-AC period compared with the pre-AC period, there was no change in recipient median (range) MELD score (24 [8-40] vs 25 [6-40]; P = .27) or median (range) acceptance sequence (15 [1-3951] vs 10 [1-1138]; P = .31). Post-AC vs pre-AC, there was no difference in 6-month wait list survival (82.6% [100 of 121] vs 78.5% [73 of 93]; P = .71), patient survival (95.5% [85 of 89] vs 89.0% [73 of 82]; P = .48), and graft survival (94.3% [84 of 89] vs 87.8% [72 of 82]; P = .37).

Table 1. Donor and Recipient Characteristics at Baylor Simmons Transplant Institute Preimplementation vs Postimplementation of the Acuity Circles (AC) Framework for Deceased Donor Liver Allocation.

| Characteristic | No./total No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-AC | Post-AC | ||

| All accepted donors | |||

| Brain-dead donors | 67/95 (70.5) | 63/118 (53.4) | .02 |

| DCD | 28/95 (29.5) | 55/118 (46.6) | |

| Livers transplanted | |||

| Brain-dead donors | 65/81 (80.3) | 57/92 (62.0) | .01 |

| DCD | 16/81 (19.8) | 35/92 (38.0) | |

| Primary nonfunction as transplant outcome | 1/81 (1.2) | 2/92 (2.2) | >.99 |

| Transplant rate | |||

| Donor organs transplanted | 81/95 (85.3) | 92/118 (78.0) | .24 |

| Donor organs declined in OR | 14/95 (14.7) | 26/118 (22.0) | |

| Recipient characteristics, median (IQR) | |||

| MELD score | 25 (21-29) | 24 (20-27.75) | .27 |

| Sequence | 10 (5-36) | 15 (4-53) | .31 |

| Cold ischemic time | 5.80 (4.78-6.60) | 5.75 (5.05-6.48) | .40 |

Abbreviations: DCD, donation after circulatory death; IQR, interquartile range; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; OR, operating room.

Mode of Transportation, Import Status, and Travel Distance

Table 2 compares the mode of transportation, import status, and travel distance between the pre-AC and post-AC allocation periods. In the post-AC period, there was no difference in the percentage of donors requiring a flight (58.5% [69 of 118] vs 56.8% [54 of 95]; P = .82), percentage of donors per nautical mile category, or mean (SD) distance traveled (155.83 [157.00] vs 140.54 [144.33] nautical miles; P = .32). However, the percentage of import donors increased significantly in the post-AC period (63.6% [75 of 118] vs 17.9% [17 of 95]; P < .001).

Table 2. Mode of Transportation, Import Status, Transportation Distance, and Fees Associated With Donors Preimplementation vs Postimplementation of Acuity Circles (AC) Framework for Deceased Donor Liver Allocation.

| Measure | No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-AC (n = 95) | Post-AC (n = 118) | ||

| Transportation and origin | |||

| Mode of transportation | |||

| Drive | 41 (43.2) | 49 (41.5) | .82 |

| Fly | 54 (56.8) | 69 (58.5) | |

| Import status | |||

| Within OPO | 77 (81.9) | 43 (36.4) | <.001 |

| Import | 17 (18.1) | 75 (63.6) | |

| Donors per NM category | |||

| <150 | 45 (47.4) | 59 (50.0) | .96 |

| 150-249 | 35 (36.8) | 40 (33.9) | |

| 250-500 | 14 (14.7) | 18 (15.3) | |

| >500 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Transportation distance from recipient city to donor city, median (IQR), NM | 144 (0-206.5) | 146 (27-207.75) | .32 |

| Fees charged | |||

| Import fee | |||

| Yes | 12 (12.6) | 37 (31.4) | .002 |

| No | 83 (87.4) | 81 (68.6) | |

| Surgeon fee | |||

| Yes | 9 (9.5) | 23 (19.5) | .05 |

| No | 86 (90.5) | 95 (80.5) | |

| Charter flight fee | |||

| Yes | 53 (55.8) | 62 (52.5) | .22 |

| No | 42 (44.2) | 56 (47.5) | |

| Total donor fees, mean (SD), $ | |||

| Accepted | 45 726 (9300) | 52 966 (13 278) | <.001 |

| Declined | 10 217 (4853) | 15 865 (3942) | <.001 |

| Acquisition and charter flights, mean (SD), $ | |||

| Acquisition fee | 39 980 (2235) | 43 816 (3266) | <.001 |

| Charter flight fee | 9049 (5140) | 12 904 (6066) | .002 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NM, nautical miles; OPO, organ procurement organization.

Fees

Table 2 also compares the fees between the 2 allocation eras. There was no difference in the percentage of donors that incurred a charter flight fee in the post-AC period vs the pre-AC period (52.5% [62 of 118] vs 55.8% [53 of 95]; P = .22). There was a 2-fold increase in percentage of donors incurring both an import fee (31.4% [37 of 118] vs 12.6% [12 of 95]; P = .002) and a surgeon fee (19.5% [23 of 118] vs 9.5% [9 of 95]; P = .05). Overall, fees were significantly higher in the post-AC period compared with the pre-AC period. The total fees per accepted donor increased 16% (mean [SD] of $52 966 [13 278] vs $45 725 [9300]; P < .001), and total fees per declined donor increased 55% (mean [SD] of $15 865 [3942] vs $10 217 [4853]; P < .001). In the post-AC period, acquisition fees increased 10% (mean [SD] of $43 860 [3266] vs $39 980 [2236]; P < .001), and charter flight fees increased 43% (mean [SD] of $12 904 [6066] vs $9049 [5140]; P = .002).

Cost Variation Within and Outside of Region

In Table 3, we show the fees associated with donors accepted from 3 cities within the transplant center region. For cities A and B, livers that crossed DSA boundaries had higher total costs than those that stayed within the DSA boundary. For city C, which is outside of the DSA for both transplant centers, the total fees were substantially higher than for cities A and B. Similarly, Table 3 also shows the fees associated with all donors outside of region 4. In all instances, the total fees were higher than $75 000. In addition to organ acquisition fees (ranging from $40 392 to $54 060), all of the donors outside of region 4 incurred import fees ($10 000 per donor), charter flight fees (more than $12 000 per donor), and surgeon fees ($2500 to $4000 per donor).

Table 3. Fees Charged for Donor Livers Originating in 3 Cities Within Region 4 and for All Livers Accepted for Transplant Outside of Region 4.

| Area | Center | OPOa | Distance, NM | Import | $ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition fee | Import fee | Charter fee | Surgeon fee | Total fees | |||||

| Donor livers originating from 3 cities within region 4 | |||||||||

| City A | C2 | A | 0 | No | 39 000 | NA | 0 | 0 | 39 000 |

| C1 | A | 27 | Yes | 45 000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 000 | |

| C1 | A | 27 | Yes | 45 000 | 10 000 | 0 | 3000 | 58 000 | |

| City B | C1 | B | 80 | No | 42 500 | NA | 2178 | 0 | 44 678 |

| C2 | B | 105 | Yes | 47 500 | 0 | 3400 | 0 | 50 900 | |

| City C | C1 | C | 166 | Yes | 48 000 | 10 000 | 8992 | 3000 | 69 992 |

| C1 | C | 166 | Yes | 48 000 | 10 000 | 9407 | 3000 | 70 407 | |

| C2 | C | 164 | Yes | 48 000 | 10 000 | 16 845 | 4000 | 78 845 | |

| Donor livers originating from outside region 4 | |||||||||

| Region 5 | C2 | E | 485 | Yes | 40 392 | 10 000 | 20 889 | 4000 | 75 281 |

| Region 11 | C1 | F | 631 | Yes | 46 800 | 10 000 | 16 727 | 2500 | 76 027 |

| Region 5 | C2 | E | 485 | Yes | 40 392 | 10 000 | 21 671 | 4000 | 76 063 |

| Region 8 | C2 | I | 296 | Yes | 44 300 | 10 000 | 17 930 | 4000 | 76 230 |

| Region 8 | C1 | G | 476 | Yes | 52 500 | 10 000 | 12 628 | 3000 | 78 128 |

| Region 3 | C1 | H | 384 | Yes | 54 060 | 10 000 | 12 247 | 3000 | 79 307 |

| Region 8 | C2 | I | 404 | Yes | 44 300 | 10 000 | 22 146 | 4000 | 80 446 |

Abbreviations: NM, nautical miles; OPO, organ procurement organization.

To protect individual OPO identities, each OPO is assigned a unique letter.

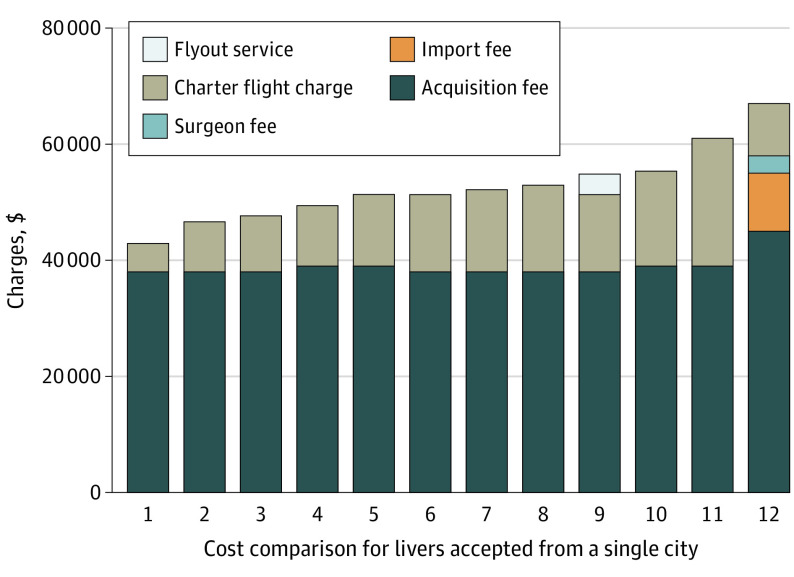

Single-City Cost Variation

The Figure demonstrates the variability of fees associated with accepted donors from a single city. There is a greater than $20 000 difference in total fees between the lowest and highest cost procurement from this city ($42 891 vs $66 997). The highest cost procurement was the only case that incurred an import fee ($10 000), a surgeon fee ($3000), and an export surcharge ($6000) in addition to the organ acquisition fee charged for local donors ($39 000).

Figure. Fee Comparison for All Livers Accepted for Transplant From a Single City.

The city is approximately 200 nautical miles from both transplant centers. It is located within the donor service area of Baylor Simmons Transplant Institute’s Center 2 and outside of the donor service area of Center 1.

Flight Fee Variation

Table 4 demonstrates the variation in flight fees for 9 selected donors. In comparing flight invoices, we found that there was a difference in flight and standby rates by center, driven by different OPO contracts with the same charter flight company. Moreover, some flights were discounted, either split with other organs or with the OPO. We also found that flights with more legs were more expensive, which we determined to represent planes that originated outside of the transplant center airport and had to be moved from the origin airport to the transplant center airport. For example, flying to and from the same city, 233 nautical miles from C2, the total charge was $14 229 for a 2-leg flight and $22 996 for a 4-leg flight.

Table 4. Flight Fees for Various Scenarios, Demonstrating the Factors Other Than Distance That Influence Costs.

| Distance, NM | Flight legsa | Split feeb | Center | Rate/h, $ | $ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight | Standby | Flight feec | Standby feed | Set feese | Total feesf | TC chargeg | ||||

| 80 | 2 | Yes | C1 | 3500 | 0 | 7000 | 0 | 1777 | 8777 | 2926 |

| 163 | 2 | No | C1 | 2600 | 0 | 6240 | 0 | 1968 | 8208 | 8208 |

| 195 | 2 | No | C1 | 2600 | 0 | 5720 | 0 | 2492 | 8212 | 8212 |

| 195 | 4 | No | C2 | 4145 | 375 | 12 435 | 2344 | 1577 | 16 356 | 16 356 |

| 195 | 2 | No | C2 | 4145 | 375 | 9119 | 2062 | 1577 | 12 758 | 12 758 |

| 268 | 4 | Yes | C2 | 4145 | 375 | 14 922 | 2963 | 1655 | 19 539 | 9766 |

| 233 | 2 | No | C2 | 4145 | 375 | 10 777 | 1875 | 1577 | 14 229 | 14 229 |

| 233 | 4 | No | C2 | 4145 | 375 | 19 896 | 1500 | 1600 | 22 996 | 22 996 |

| 384 | 2 | No | C1 | 3500 | 0 | 10 150 | 0 | 2097 | 12 247 | 12 247 |

Abbreviations: NM, nautical miles; TC, transplant center.

Number of flights charged on the invoice.

Flights for which the total charge was split among organs or between the OPO and transplant center.

Calculated as flight rates multiplied by flying time.

Calculated as the standby rate multiplied by standby time.

Includes pilot fees, airport fees, and landing fees.

Sum of all fees.

Charge to the transplant center.

Discussion

Donor and Recipient Characteristics

UNOS modeling prior to AC allocation implementation predicted an increase in median MELD score at transplant, organs flown, and median transport distance.1 The increased percentage of organs flown was predicted to increase the cost of organ acquisition. This study found that AC allocation did not affect the median recipient MELD score, median sequence at transplant, 6-month wait list mortality, patient survival, graft survival, or transplant rate at BSTI. There was no difference in cold time or primary nonfunction. The low and unchanged median MELD score at transplant is likely because Texas is a large state, and the 500–nautical mile circles around our transplant hospitals reach into Texas, the Southeast, and the Midwest, areas that have a lower median MELD score at transplant compared with the coasts of the US. In addition, there was no difference in the percentage of organs flown, median transplant distance, or distribution of donors by nautical mile category, which is consistent with a 2021 study of changes in regional travel distance in which the change in median travel distance in region 4 was slightly decreased in the post-AC period.10 The most striking change in organ procurement characteristics found in this study is a 45% increase in import livers in the post-AC period.

OPO Fees Associated With Imports

While it has been shown that import organs have higher OPO costs because they are included in the cost report of both the exporting and importing OPO,5 to our knowledge, the effect of imports on the cost of organ acquisition at the level of transplant centers has not previously been studied. This study identified multiple reasons for increased fees associated with organs that cross DSA boundaries. First, the 2 OPOs that serve our transplant centers add an export surcharge of $5000 to $6000 to the organ acquisition fee for organs that cross DSA boundaries. We cannot definitively state that other OPOs add export surcharges, but we recommend that further study of the prevalence of export surcharges nationwide is made a priority by transplant centers and UNOS. OPOs that charge export surcharges should provide justification for the additional fee because the costs of donor management, operating room, and staff time should be consistent regardless of recipient location, and if there is no reason for export surcharges, OPOs should set a single, standard organ acquisition fee for livers regardless of recipient DSA.

Second, most import livers accepted were charged an import fee of $10 000, and one OPO charged an import fee of $6500 for declined organs. As with export surcharges, import fees may not be charged by all OPOs nationwide. While there are scenarios in which import fees may make sense, such as having the recipient OPO provide preservation fluids and surgical coordination, there are other scenarios, like setting up charter flights or managing a donor invoice, in which a $10 000 charge seems exorbitant. Of note, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, BSTI changed fly-out procurement practices to send only the transplant surgeons, using on-site surgical coordinators and supplies owing to OPO staff travel restrictions. Despite this change in practice, which should decrease the importing OPO costs associated with liver acquisition, we continue to incur the same import fees for most import donors. While we would like to call for the elimination of import fees, we can only do this if there is consistency in donor practices across transplant centers. For example, if all centers use local staff and supplies, recipient OPOs can charge lower import fees for invoice and transportation coordination. Alternatively, transplant centers could take ownership of import coordination, bypassing local OPOs and avoiding import fees.

Further research is needed to determine the prevalence of surgeon fees across OPOs, and ultimately, we believe surgeon fees should be eliminated. For local donors (ie, donors within the recipient center DSA), the organ acquisition fee pays the surgeon fee, so there is no reason why the organ acquisition fee for an import/export organ cannot cover the surgeon fee, especially given the export surcharge added to the organ acquisition fee for imports.

Flight Fees

We also found that the charter flight fees increased in the post-AC period, and the increase cannot be explained by more flights or increased flight distances. Other factors, such as flight rates, standby rates, flight legs, and split fees, had more of an influence on flight fees than distance alone.

Changes in Practice at BSTI

Based on the findings of this study, BSTI has made several changes to our liver import practices. We now exclusively fly from the origin airport of the plane fleet rather than from the airport closer to one of our transplant hospitals, which adds about 20 minutes to the ground transport time and saves $2000 to $5000 per charter flight. When we accept a liver offer from a local OPO outside of the recipient DSA, we ask if they are sending a surgical team to the donor from our local area, and if so, our surgeons travel with their team so we share transportation costs with the donor OPO in some circumstances and avoid import fees and surgeon fees by not involving the importing OPO. Finally, we give preference to donors within the DSA of the transplant hospital when multiple donors are available for a patient. The changes that we have made may not be cost saving for other liver transplant centers, so we recommend that centers evaluate their costs as we have done to identify practices that will be more cost-effective in their local environment.

Recommendations for National Changes

On a larger scale, we worry that the higher costs associated with import livers will affect transplant center practices and perpetuate geographic disparities in liver allocation, and we recognize that there are only limited options for transplant centers to avoid the higher fees associated with imports. To make widespread and impactful changes in the cost associated with organ acquisition, we believe that there needs to be a national discussion between payers, transplant centers, professional organizations, OPOs, and UNOS to generate regulations that define limits on the amount and types of fees that can be charged for organ acquisition. We must insist on transparency in how charges are determined and applied as well as consistency in OPO practices. Moreover, if the increased costs associated with AC allocation cannot be mitigated with regulations on the fees associated with imports, this may provide an impetus to change the framework for allocation again.

Limitations

This study is limited by data from a single transplant institute. However, the fact that we were able to compare the costs of 2 transplant centers in different OPOs that use the same charter flight company, airport, and surgeons and share patients allowed for direct comparison of costs between import and local donors. The geography of Texas explains why the mode of transportation and travel distance did not change in the post-AC era. This is not the case with other transplant centers, so there is likely variability in the financial impact of AC allocation across programs. Therefore, more research is needed to determine if the findings in this study are generalizable across transplant programs in the US.

In addition, the time frame immediately following the AC policy change coincided with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a major effect on organ donation and could have impacted the location and availability of donors. Therefore, longer-term data are needed to determine if the differences in the costs associated with liver acquisition during this initial period was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that higher fees were associated with import organs and that import fees, surgeon fees, and charter flight fees were all increased in the post-AC era for BSTI. AC allocation eliminated DSA boundaries for the purposes of organ allocation but did not address the costs associated with moving organs across these boundaries. There is an urgent need to standardize and regulate the charges associated with organ acquisition to maintain the financial viability of transplant programs. We believe that action to curb the growing cost of liver acquisition is both essential and urgent, requires the involvement of all interested parties, and cannot be ignored just because it is complicated.

eFigure. Outline of fees associated with organ acquisition.

References

- 1.OPTN/UNOS Liver and Intestine Transplantation Committee . Liver and intestine distribution using distance from the donor hospital: briefing paper. Accessed December 21, 2019. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2766/liver_boardreport_201812.pdf

- 2.Organ Procurement and Transplant Network . Executive summary of OPTN approval of policies to eliminate the use of DSAs and regions in liver allocation. Accessed December 21, 2019. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2779/board_executivesummary_liver_201812.pdf

- 3.Chyou D, Karp S, Shah MB, Lynch R, Goldberg DSA. A 6-month report on the impact of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing acuity circles policy change. Liver Transpl. 2021;27(5):756-759. doi: 10.1002/lt.25972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Medicare: Provider Reimbursement Manual part 1—Chapter 31, organ acquisition payment policy. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/downloads/R471pr1.pdf

- 5.Kappel DF, Chapman WC, Conrad S, et al. Organ procurement organization liver acquisition costs could more than double with proposed redistricts. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(8):2269-2270. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez H, Weber J, Barnes K, Wright L, Levy M. Financial impact of liver sharing and organ procurement organizations’ experience with Share 35: implications for national broader sharing. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(1):287-291. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agopian V, Verna E, Goldberg D. Changes in liver transplant center practice in response to coronavirus disease 2019: unmasking dramatic center-level variability. Liver Transpl. 2020;26(8):1052-1055. doi: 10.1002/lt.25789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. ; REDCap Consortium . The REDCap Consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheetz KH, Waits SA. Outcome of a change in allocation of livers for transplant in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(5):496-498. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Outline of fees associated with organ acquisition.