Abstract

Objective: We describe qualitative results on facilitators and barriers to participating in a family mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) for youth with ADHD and their parents and perceived effects on child and parent. Method: Sixty-nine families started the 8-week protocolized group-based MBI called “MYmind.” After the MBI, individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of parents (n = 20), children (n = 17, ages 9–16 years), and mindfulness teachers (n = 3). Interviews were analyzed using Grounded Theory. Results: Facilitators and barriers regarding contextual factors (e.g., time investment), MBI characteristics (e.g., parallel parent–child training), and participant characteristics (e.g., ADHD-symptoms) are described. Perceived effects were heterogeneous: no/adverse effects, awareness/insight, acceptance, emotion regulation/reactivity, cognitive functioning, calmness/relaxation, relational changes, generalization. Conclusion: MYmind can lead to a variety of transferable positively perceived effects beyond child ADHD-symptom decrease. Recommendations on MYmind participant inclusion, program characteristics, mindfulness teachers, and evaluating treatment efficacy are provided.

Keywords: mindfulness, ADHD, qualitative research, child, parenting

Introduction

Having ADHD can have an important impact on the life of children with ADHD and their parents. Symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity are at the core of this neurodevelopmental disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, the ADHD population is very heterogeneous regarding profiles of core symptoms, co-morbidities (e.g., sleep, mood, anxiety, substance use, autism spectrum disorders [ASD]), cognitive deficits (e.g., in cognitive control, reward sensitivity, timing), functional impairment (e.g., school failure, family conflict, low self-esteem) as well as positive traits (e.g., creativity, integrity, energy, humor) (Faraone et al., 2015; Sedgwick et al., 2019). Quality of life of children and their parents is negatively affected by child-ADHD, and rated lower in the presence of co-morbidities of the child and negative perceptions of the parent regarding the experience of raising a child with ADHD (Cappe et al., 2017; Hakkaart-van Roijen et al., 2007). Furthermore, parental psychopathology—which is more prevalent among parents of children with ADHD—has an impact on parenting, the child’s mental health and reduces efficacy of evidence-based treatments for child-ADHD (Deault, 2010; Evans et al., 2018b; Rasmussen et al., 2018). Family mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) is a new approach in the treatment of child-ADHD with the potential to improve the lives of both children and parents (Bögels et al., 2008). At this early stage along the intervention development and evaluation trajectory (Medical Research Council [Dunning et al., 2019)]), qualitative research can be used to inform and optimize treatment programs, assessment batteries and implementation. We describe a qualitative study to gain insight in facilitators and barriers to participate in a family MBI, and to explore the scope of perceived treatment effects of children with ADHD and their parents.

Mindfulness is often defined as the trainable capacity to pay attention to experiences in the present moment, on purpose, in a non-judgmental, non-reactive, and openhearted way (Kabat-Zinn, 1990, 2003). One proposed mechanism of mindfulness meditation is that attention control, emotion regulation, and self-awareness are core components that jointly enhance self-regulation (Tang et al., 2015). Impairments in self-regulation are implicated in various psychiatric disorders like ADHD, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse, which explains the impact mindful awareness can have on a broad range of psychopathology (Wielgosz et al., 2019). In family MBI, both intrapersonal and interpersonal processes play a role. Examples of mindful awareness in the parent–child relationship are “attention in listening to the child,” “reactivity in parenting,” and “responsiveness to child’s needs and emotions” (Duncan et al., 2009).

Most MBI’s used in a clinical setting are based upon the 8-week group Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program of Kabat-Zinn (2011). MBI’s have been adapted to be applied in children and also to cultivate mindful parenting. A meta-analysis on the effects of MBI’s in children and adolescents demonstrated positive effects on executive function, attention, negative behaviors, depression, anxiety/stress, and mindfulness (Dunning et al., 2019). A meta-analysis on mindful parenting training showed reductions of parenting stress which in turn had a positive effect on externalizing and cognitive outcomes of the child (Burgdorf et al., 2019). Regarding families with a child with ADHD specifically, MBIs for children and/or their parents resulted in improvements for children in ADHD-symptoms, internalizing and externalizing behavior, academic performance, and parent-rated social functioning and self-esteem; parents improved on ADHD-symptoms, satisfaction, and happiness; and improvements in parent–child relationships were found (Cairncross & Miller, 2020; Evans et al., 2018a; Zhang et al., 2018). However, most of these studies were small, uncontrolled, non-randomized, and/or had unblinded raters). Except for ADHD-symptoms, little is known about what other outcomes would be relevant to assess. To address methodological limitations of previous studies, we initiated the MindChamp study (Siebelink et al., 2018): a well-powered pre-registered RCT of a family MBI for children with ADHD and their parents. Alongside this RCT, we conducted qualitative research to allow a more open bottom-up exploration of personal narratives and do more justice to the heterogeneity of experiences and the perspective of the people receiving healthcare (Greenhalgh et al., 2016).

The aim of the present qualitative study is to gain insights in facilitators, barriers, and perceived effects of participation in an MBI for families with a child with ADHD (MYmind). For this, we conducted semi-structured individual interviews with both parents and children (aged 9–16 years) who participated in the MBI, and mindfulness teachers who administered the intervention. The present study builds on a previous mixed-method pilot study on MYmind for children aged 8 to 12 years and their parents (N = 11 families) from Hong Kong, which was conducted in an entirely different geographical location and culture (Zhang et al., 2017).

Methods

Study Design

This qualitative study is conducted along with the MindChamp RCT which examined the additional value of a family MBI to care-as-usual for children with ADHD and their parents. The study protocol was ethically approved by CMO Arnhem-Nijmegen and registered under number 2015–1938. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and children from the age of 12. The interviews were scheduled at least after the 2-month follow-up assessments for the RCT. We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ; Tong et al., 2007; see Supplemental Table 1).

Participants

Interviews were conducted with parents and children who received family MBI, and mindfulness teachers who provided the training. Participants were derived from four different MBI groups, across a period of 1 year. Eligibility criteria were: (a) child has a clinical ADHD diagnosis based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), (b) child is 8 to 16 years old, (c) child and parent have an estimated IQ > 80, (d) child and parent have adequate mastery of Dutch language, and (e) child and parent have no psychosis, bipolar illness, active suicidality, untreated posttraumatic stress disorder, or substance use disorder that impedes functioning.

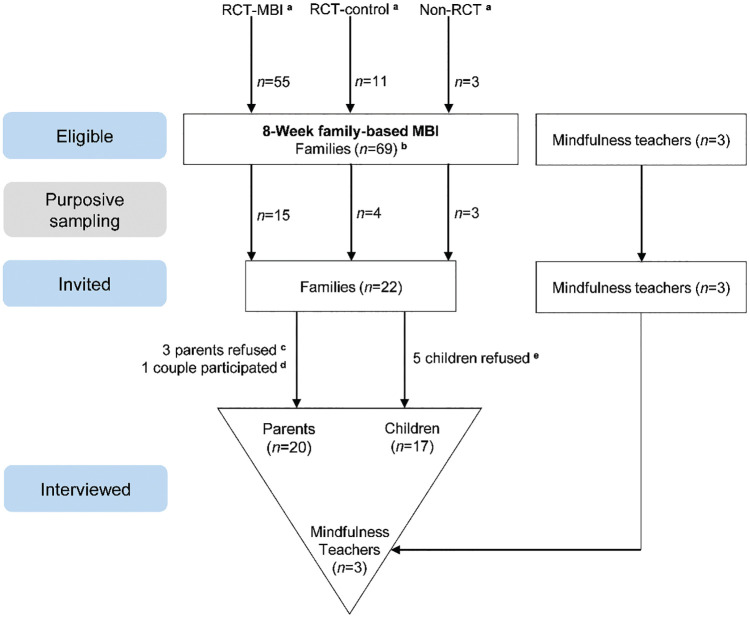

Purposive sampling was used to obtain a diverse sample reflecting a broad scope of experiences and views (Boeije, 2016). To this end, we first recruited families that were eligible at the time the interviews started. In the next step, we recruited all subsequently eligible families that would help diversify the sample regarding child age, ethnical background, ADHD-medication use, and MBI attendance. Sampling ended when data saturation was reached, that is, when no new relevant knowledge was being obtained from new participants (Tong et al., 2007). Finally, 20 parents (n = 6 fathers) and 17 children (9–16 years old, n = 10 boys) from 19 families (demographics in Table 1), and all mindfulness teachers (n = 3, all female) participated in the qualitative study (Figure 1). Three families that discontinued with the MBI were approached for an interview, but only one parent approved to participate. Eighteen families completed the MBI with an average attendance rate of 7.4 out of 8 sessions (range 5–8).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Interviewed Participants After the MYmind Mindfulness-Based Intervention: Children With ADHD (n = 17) and Their Parents (n = 20).

| Characteristics | Children | Parents |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years at interview, M (range) | 12 (9–16) | 45 (38–59) |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 10 (59) | 6 (30) |

| Intelligence quotient (IQ), n (%) | ||

| Low Average (80–89) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Average (90–109) | 7 (41) | 5 (25) |

| High average (110–119) | 4 (24) | 4 (20) |

| Very high (120–129) | 2 (12) | 3 (15) |

| Extremely high (130 and higher) | 1 (6) | 3 (15) |

| Missing | 1 (6) | 5 (25) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Special needs primary education | 2 (12) | |

| Primary education | 9 (53) | |

| Secondary education | 6 (35) | |

| Secondary vocational education | 3 (15) | |

| Higher professional education | 10 (50) | |

| University education | 6 (30) | |

| Missing | 1 (5) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Western European | 15 (88) | 18 (90) |

| Arabic | 1 (6) | 1 (5) |

| East Asian | 1 (6) | |

| Eastern European | 1 (5) | |

| ADHD-medication, n (%) | 11 (65) | — |

| Previous ADHD-treatment, n (%) | 16 (94) | — |

| Comorbid diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| No | 11 (65) | — |

| Yesa | 5 (29) | — |

| Missing | 1 (6) | — |

Dyslexia/language disorder (n = 2), autism spectrum disorder (n = 2), Tourette’s disorder (n = 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study.

Note. RCT = randomized controlled trial; MBI = mindfulness-based intervention.

aMBI participants were primarily families that were randomized to the intervention-group for the MindChamp RCT (RCT-MBI). If there were remaining places on the MBI, these were filled with families who had already completed the control-group of the RCT (RCT-control), and families that only participated in the qualitative study.

bn = 6 discontinued.

cReasons: lack of time and interest.

dOf one family, both parents participated in the MBI and in the qualitative study.

eReasons: lack of time and interest (n = 3), interviewing was considered too demanding for the children (n = 2).

Intervention

MYmind MBI (Bögels, 2020) comprised eight weekly 90-min group sessions for children with ADHD, and parallel group sessions for parents. The child-group with one mindfulness teacher and a co-teacher was separate from the parent-group with another mindfulness teacher. Only parts of session 1, 5, 8, and the follow-up session took place together. Groups started at 4:30, 6:00, 6:30, or 7:30 p.m. and consisted of five to eight families. The program consisted of regular mindfulness exercises (e.g., sitting meditation, body scan, breathing space) alternated with yoga and exercises addressing specific issues of families with a child or adolescent with ADHD (van de Weijer-Bergsma et al., 2012; van der Oord et al., 2012). Children were taught to practice non-reactivity and to be aware of impulses and judgments in a friendly, curious way. Parents were taught mindful parenting, including mindfulness skills and compassion for themselves. Daily homework was required (15 and 30–45 min for child and parent, respectively), for 6 days a week, supported by a child- and parent-workbook and audio-meditations. A reward system was incorporated to motivate children for the sessions and at-home practice. The mindfulness teachers closely adhered to the MYmind program. In groups with children with comorbid ASD, mindfulness teachers made practices predictable and used less metaphors. Three experienced mindfulness teachers were involved, with a background in educational studies and/or social work with children with special needs. All mindfulness teachers met internationally acknowledged quality criteria (see Siebelink et al., 2018), in accordance with UK Network for Mindfulness-Based Teachers (2011).

Procedure

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted. Parent interviews were conducted by experienced and certified female interviewers (SK and CG), child interviews also by two trained female research interns (FvH and JH), and mindfulness teachers by SK. Interviewers were not involved in providing the MBI or conducting assessments for the RCT. SK invited participants by phone. Prior to the interviews, the researchers explained their reasons for the interview, as well as their role in the qualitative study. Interviews took place at a location preferred by participants, mostly their homes. In a few cases other family members were at home but they did not interfere with the interview. The interviewers followed a pilot-tested topic guide (Supplemental Table 2) and used open-ended questions (e.g., “Can you tell me about the mindfulness homework?”). Participants were also asked about possible adverse effects. Researcher observations from the interview were kept in a logbook. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. In the member-check all participants agreed on the accuracy of the transcription of their interview and did not censor the content. No repeat interviews were carried out. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes.

Qualitative Analysis

The transcripts of the interviews were analyzed based on Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 2008) using a qualitative software package (Atlas.ti version 8.0, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). That is, participants’ quotes were the starting point leading to the creation of (sub)themes; a bottom-up approach. After familiarizing with the data of the first interviews, researchers started focused coding of the data segments that were relevant for answering the research question. Two researchers coded independently, followed by comparing codes and discussing differences to derive inter-coder reliability. The obtained list of codes was used for the successive interviews in order to efficiently address further information gaps. This way, data collection and analysis alternated, following an iterative process (Charmaz, 2014). This process included the construction of themes and subthemes by combining codes during a meeting with AS, CG, SK, and FvH. Any further adjustments to the codes or themes were made after discussion and verification of the data by at least two of the researchers, subsequently proposed to the whole team. These steps were repeated where needed until agreement among all authors was reached. Participants were not involved in the analyses of the data.

Results

Two result sections on (1) facilitators and barriers and (2) perceived effects are divided into a main section based on the interviews with parents about themselves and about their children, and a triangulation section based on the perspectives of children and mindfulness teachers.

Facilitators and Barriers

Three broad themes of perceived facilitators and barriers were extracted from the parent interviews: (a) contextual factors, (b) MBI characteristics, and (c) participant characteristics. These themes could be further divided into subthemes, respectively: (a) participating as a family, where and when, and time investment, (b) content of MBI, mindfulness teachers, and other participants, and (c) personal characteristics, view on mindfulness, and child age. All (sub)themes could act as both facilitator and barrier, and applied to both parents and children (except child age). Illustrative quotes per subtheme are provided in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4.

Contextual factor: Participating as a family

The main facilitator, mentioned by almost every parent, was that parent and child acted as a co-teacher for each other. Parents reminded their children of the MYmind homework, guided them in how to practice or adapted the environment to facilitate their children’s practice. In turn, children reminded their parents to apply learned mindfulness practices in stressful situations. Other facilitating elements for parents were support and involvement of their partner and their love for their children. Barriers were interference of the MBI with the regular family structure for both parents and children. Further, the MBI evoked jealousy of some siblings and some children were embarrassed to practice at home with family members present.

Contextual factor: Where and when

Children found the time slot of the MBI sessions hindering (just before or just after dinner time, or ending too late), especially when combined with long traveling. On the other hand, traveling was sometimes experienced as quality time together. For both children and parents, overlap of the MBI sessions with other activities were perceived as a barrier. Furthermore, parents’ opinions on the MBI locations were mixed, but rooms also varied across groups.

Contextual factor: Time investment

For both parents and children, the joint parts of the MBI (e.g., practicing mindfulness together; talking about the MBI) was perceived as positive quality time together, which motivated them to continue the MBI. However, they also struggled making time for the MBI and considered the homework too time-consuming. For parents, a busy schedule and everyday hustle and bustle were perceived to be most limiting in attending the MBI, home practice and applying learned techniques. Most families did not continue longer meditations after MBI completion because it was too time-consuming. On the other hand, most did continue the “breathing space” and/or informal mindfulness practices.

MBI characteristics: Content of MBI

Within this subtheme parents considered the variety in training content and practices, supportive materials, and parallel training as facilitating. Forming a shared language was perceived as an opportunity to remind each other to be mindful (e.g., “you’re on the highway” when reacting on autopilot). From many interviews it emerged that both parents and children found the “breathing space” easy and helpful to implement in daily life. Some parents missed depth and preferred longer sessions, others considered the sessions rather long with regard to time investment. Several parents thought more sessions were necessary to fully implement mindfulness in their lives. For most children, the 1.5-hr sessions with one short break were too long regarding their abilities to concentrate. Lack of movement during meditations was also mentioned as barrier for children; the yoga-exercises were essential because they allowed them to physically move.

MBI characteristics: Other participants

This was a key facilitator for parents, especially the opportunity to exchange (sharing and hearing) experiences with parents of children with ADHD. Feeling supported and understood by others was facilitating. On the other hand, strong personalities and other parents harshly expressing their opinion were perceived as barriers. Few described a small group size as a barrier, as there were only a few others to connect with. For children, being in a group with other children with ADHD made them feel connected and they recognized themselves in one another. However, it was sometimes perceived as a barrier when other participants expressed excessive hyperactive or unpredictable behavior.

MBI characteristics: Mindfulness teachers

Most parents felt supported by the mindfulness teachers and mentioned their overall pleasant attitude, expertise, and understanding. Also, the pleasant, calming voice of a teacher was often mentioned. On the other hand, some parents and children thought that teachers should lead the group more strictly and address strong personalities in the group more directly. For one parent this resulted in being reluctant to share personal experiences and feelings in the group.

Participant characteristics: Personal characteristics

Limiting factors for parents were falling back into old habits like being on auto-pilot and rushing on in everyday life. Experiencing ADHD-symptoms themselves was considered both a barrier and facilitator. One father with ADHD perceived lack of concentration and being distracted easily while practicing mindfulness as a barrier. On the other hand, a mother reported that being less mindful because of her ADHD-symptoms was motivating her to practice mindfulness. Being conscientious such as making personal deadlines and structuring the practice of mindfulness tasks was found helpful by the parents. For children, ADHD-symptoms and comorbidity (e.g., ASD, behavior disorders or Tourette’s disorder) were mentioned as barriers due to difficulty concentrating on the exercises and processing information, overstimulation, the urge to move, and oppositional behavior. Having a social nature was reported as a facilitator for children to participate in the group.

Participant characteristics: View on mindfulness

Mindfulness was viewed as an alternative for ADHD-medication by some parents and children, which motivated them to start and/or keep up with the MBI. Other parents saw MBI as a possibility to support their children alongside ADHD-medication. Investing in mindfulness now for future use was another facilitating view. Parents described this as “planting a seed” or “owning a toolbox with mindfulness exercises” ready for use when a specific situation calls for it. One parent reported her aversion against the “bodyscan” exercise and for one child his aversion to mindfulness exercises in general was a barrier. Some parents felt sceptical about mindfulness at first, but this feeling changed as they noticed mindfulness was helpful.

Participant characteristics: Child age

Variations in age in the child group were perceived as barriers by parents. Furthermore, parents described barriers for their children such as the inability to grasp the essence of mindfulness, a lack of insight in causes and effects and difficulty with initiating practices. Parents related those barriers with their child “being (mentally) too young.”

Triangulation (based on child and mindfulness teacher interviews)

Contrary to what parents said, age differences in the child-group were not perceived as barriers by children. Most children mentioned that they connected with other group members, regardless of age. One child had expected in advance that the children would be “weird and a bit crazy,” but they turned out to be quite ordinary. Most children liked being in the group because they could be themselves and felt accepted. What decreased the mutual connectedness in the group was when other children were too noisy and excessively hyperactive. Children wanted the mindfulness teachers to interfere, but this did not always happen. On the other hand, the non-judgmental attitude, as well as the calm approach of the mindfulness teachers were important facilitators for children. Further, contrary to the parents, children did not mention negative experiences concerning the training room.

In general, mindfulness teachers’ views were in line with the statements made by parents on perceived facilitators and barriers. They stressed the facilitating effects for the participants of attending MBI as parent–child dyad and with a peer group, but also acknowledged challenges with severe disruptive child behavior and parental psychopathology (e.g., ASD). A low-stimulus room for the child sessions was recommended by mindfulness teachers. Further, time pressure by following the protocol during MBI sessions was a barrier for teachers, especially when parents felt the need to share experiences. Some parents also wished to discuss more practical parenting issues. Furthermore, all teachers wanted to have more say in who was included in the MBI. They had doubts regarding the inclusion of children with severe behavioral problems (e.g., oppositional deviant disorder), the low age-limit of 8 years and the low IQ-limit of 80. Further, they preferred not too many children per group (e.g., 6/7) within roughly the same age range (e.g., max. 3 years apart). Lastly, the medication dose of the children was essential for teachers to provide the MBI properly. That is, too much medication resulted in apathy, worn off or forgotten medication could result in excessive hyperactivity and disturbing the group.

Perceived Effects

Perceived effects for both the participating children and parents, as reported by the parents, could be fitted into eight themes: (a) no/adverse effects, (b) awareness/insight, (c) acceptance, (d) emotion regulation/reactivity, (e) cognitive functioning, (f) calmness/relaxation, (g) relational changes, and (h) generalization. Illustrative quotes per theme are provided in Supplemental Tables 5 and 6.

No/adverse effects

Many parents initially described that their children experienced little to no effects, especially regarding their ADHD-symptoms. However, as the interviews moved on, all participating parents described several specific perceived effects, as summarized below. Although ADHD-symptoms did not disappear after MBI, improvement was perceived in ADHD-related symptoms and/or other domains. Further, adverse effects were mentioned regarding homework and the reward system: parents felt pressured by the amount of homework for themselves and felt guilty when they did not manage to help the child; children were disappointed when they did not get all points and felt frustrated when other children got their points unfairly (i.e., ticking off, while they did not actually practice at home). In addition, one specific adverse effect was described: a child was more (hyper)active in the evening following a mindfulness session. In contrast to her mother who was calm and relaxed after the session, the daughter showed enthusiasm, talked much, and had a desire to be physically active and eat.

Awareness and insight

Increased intrapersonal awareness for parents and children concerned bodily sensations, thoughts, behaviors and habitual patterns. On an interpersonal level, parents described that their awareness of their child’s problems increased through the MBI, and that they became aware of their critical view of their child. Children became more aware of their own emotions, (ADHD-related) behavior, the effects of this behavior on others and vice versa. Furthermore, parents gained insights into their own needs, behavior, parenting, and their underlying views. Parents experienced the importance of spending time alone, but also mindfully spending time with their child. Parents and children developed more insight in and empathy toward each other’s emotions, needs and behavior, and that of other family members.

Acceptance

Parents experienced self-acceptance and the ability to be kinder toward themselves. Besides, parents described that they accepted others more as well, mainly their children with ADHD, but also their partner with ADHD-characteristics, if applicable. One parent described that she now stopped trying to fit her daughter and the rest of the family into norms or standards of others. For children, self-acceptance improved for both their ADHD-behavior and cognitive functioning.

Reactivity and emotion regulation

Parents reported becoming less reactive toward their children; thinking more about their responses, instead of reacting automatically, and by doing so getting angry less quickly. Parents and children used the “breathing space” frequently. It helped them to regulate emotions in challenging situations and respond more calmly and in control. In addition, by pausing or turning away from stressful situations at school or at home, they managed to react less impulsively.

Cognitive functioning

Improved cognitive functioning comprised different forms of attention, planning, and keeping structure. One parent described how his functioning at work improved through breaking down his work in smaller tasks, creating overview and improving his ability to plan and estimate quantity, as a result of “taking distance from a mindfulness perspective.” Furthermore, parents mentioned getting a clearer overview in stressful situations, as well as being better in determining a strategy to deal with challenging situations. The children started planning more themselves and some became less forgetful after the MBI.

Calmness and relaxation

Parents described that they felt more relaxed in general and that they were better able to find peace in themselves. In addition, they took mental and physical breaks more often to relax or calm down. Further, some parents mentioned that the “bodyscan” helped them or their children to better fall asleep. Several parents said that their child had learned to actively seek moments of rest, for example, finding a quiet place at school when they felt their environment was too busy and stressful. By doing this, children felt and behaved calmer in general.

Relational changes

All parents described relational changes. They experienced an increasingly warmer relationship with their child with ADHD. Both quality and quantity of conversations increased, in some cases resulting in the prevention of conflicts. Parents mentioned their children had fewer quarrels at home and at school. Parents and children shared experiences, helped each other, and allowed feedback. Acceptance and understanding grew. Some parents lowered their expectations for their child because they became aware that what they viewed as unwillingness was often inability. Others now saw that their child had more abilities than they thought, resulting in giving more responsibilities and being less controlling. Besides, relationships with other family members improved as well.

Generalization

Generalization beyond MBI context entailed the transfer of effects to school, work, leisure time activities, and other social contacts. A few parents described using mindfulness for their own personal growth and development. For example, one father approached all sorts of situations in a more mindful way; instead of acting immediately and wanting to be in control, he stepped back and took a pause to reflect on the situation. One parent wanted to become a mindfulness teacher herself after following the MBI. Teachers at school mentioned to parents that children were able to focus better and behave more calmly. Improvement of school results was reported, as well as general functioning at school. For children, altered social interactions (at school) resulted in making new friends. One parent mentioned her child enjoyed going to school again since the MBI.

Triangulation (based on child and mindfulness teacher interviews)

The gathered information from parents about perceived effects was supported by interviews of the children. One perceived effect was more pronounced in children, which was the use of mindfulness (specifically the “bodyscan”), to prepare themselves for sleep and falling asleep faster.

Overall, mindfulness teachers confirmed the perceived effects described by parents. Additionally, they mentioned that mindfulness helped parents with being aware of (parental) stress or reducing (parental) stress. Also, the adverse effect of the reward system was confirmed: for some children it mainly brought experiences of failure. One mindfulness teacher suggested to target the parents for home practice; to let them be a role model.

Discussion

This qualitative study provides a rich systematic exploration of facilitators, barriers, and perceived effects that are considered important by the people receiving and providing a family MBI in the treatment of child-ADHD. This study builds on previous mixed-method research from Hong Kong (Zhang et al., 2017). We described facilitators and barriers within the following key themes: contextual factors, MBI characteristics and participant characteristics. A facilitator that stood out was the parallel parent–child training design. Among others, this motivated families to adhere to the MBI. Due to a paucity of studies, it is yet unknown to what extent family-based interventions enhance treatment effects compared to child- or parent-only MBI (Zhang et al., 2018). “Time” in the context of planning and time investment was a pronounced barrier for both parents and children, consistent with findings of Zhang et al. (2017). The MYmind program asks at least twice the time investment for the mindful parenting part than what is considered feasible according to a qualitative co-design study with stressed parents of children with ADHD, and healthcare providers working with this population (Ruuskanen et al., 2019). Therefore, future studies could examine the efficacy of a program with less homework, sessions, and/or shorter practices (e.g., Honggui et al., 2020), or with a different schedule such as a weekend training (e.g., Taren et al., 2017), and whether this could attract a larger proportion of families with a child with ADHD who are in need of help. Another format used for people for whom a classic MBI (i.e., 8-week group-based) might be too demanding is an internet-based program; not yet investigated as family MBI for ADHD as well. Although this provides flexibility in when, where and how participants engage in MBI, the absence of practicing in the presence of a peer group as well as the type of participant-teacher contact are examples of barriers (Compen et al., 2017). Other participants, the physicality of some practices and the positive attitude of the mindfulness teachers were also pronounced facilitators for parents and children in the present study. However, too disruptive behavior of other participants was a barrier. Extra guidance beyond the MYmind program was required for children with more severe externalizing behavior, like in Zhang et al. (2017). The mindfulness teachers also stressed the importance of well-adjusted ADHD-medication. Whereas hyperactive-impulsive behavior could be a barrier for other participants, inattentiveness was rather an internal barrier. Nevertheless, also for children with hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, group-based MBI has advantages: Being confronted with the behavior of others enabled positive recognition, awareness and insight of one’s own behavior and created an ecologically valid learning situation with distractions. Parental ADHD-symptoms were also a motivator as parents expected MBI to be helpful for ADHD. Hence, psychological symptoms of parents could improve compliance with family MBI.

Concerning the results on perceived effects, eight themes were found: no/adverse effects, awareness/insight, acceptance, emotion regulation/reactivity, cognitive functioning, calmness/relaxation, relational changes, and generalization. Themes included mindfulness-specific (e.g., increased acceptance and compassion, less reactivity) and more general perceived effects (e.g., improved relationships). The initial reaction of parents regarding effects of the MBI was often no or little perceived effect on ADHD of the child, although when interviews progressed also ADHD-related perceived effects were mentioned (e.g., less reactive, more calm, improved concentration). A possible explanation is that effects did not match the initial expectations or hopes of families. Further, lower (developmental) age was mentioned in the context of less effect for children; another MBI program may be better suited for younger children (Lo et al., 2020). Few studies on MBI for ADHD have evaluated adverse effects and relied on patient-initiated comments (Mitchell et al., 2018). We actively inquired and also found no serious adverse events like psychosis, mania, depersonalization, anxiety, panic, traumatic memory reexperiencing, and other forms of clinical deterioration (Van Dam et al., 2018). It is possible that these effects are more likely to occur when meditating more intensively than instructed in MYmind. Moreover, in the recruitment phase, participants were excluded in the presence of severe disorders. However, adverse effects were mentioned regarding the homework reward system, contrasting results of Zhang et al. (2017). Many parents and children did not manage to accomplish all required homework, which could have a stress-inducing effect; also found in behavioral parent training for child-ADHD (Allan & Chacko, 2018). The reward system likely reinforced this process because there was more at stake and also triggered children’s perception of injustice. However, some children and one mindfulness teacher considered the reward system helpful.

The heterogeneity of perceived effects, and the effect themes are consistent with pilot qualitative research on MYmind for ADHD (Zhang et al., 2017) and ASD (Ridderinkhof et al., 2019). Many of these effect domains are often not assessed as MBI trial outcomes. For example, quality of the parent–child relationship is not assessed in the MindChamp RCT (Siebelink et al., 2018), although this would be indicated based on the qualitative results and literature showing the importance of this relationship on children’s mental health and behavior problems (McPherson et al., 2014). Meta-analyses on MBI trials for ADHD focus on ADHD-symptom reduction because this is the most consistent reported outcome. However, researchers’ views on what is the most important treatment effect may not match patients’ (Huber et al., 2016). Moreover, a substantial group of children have remaining ADHD-symptoms after receiving evidence-based treatment (Molina et al., 2009). For these children, outcomes like quality of life or acceptance might be also relevant. There is currently no core outcome set for clinical trials in ADHD (Padilha et al., 2018), although this would allow to look beyond ADHD-symptoms only (Kirkham et al., 2013). Measures of functionality, quality of life, adaptive life skills, and executive function are considered important to assess as additional treatment responses (Epstein & Weiss, 2012). Another consequence of the heterogeneity of perceived effects is that as a result of the different individual responses to treatment, measuring average effects might not do justice to possible effects that the MBI could have on subgroups. We formulated several recommendations regarding the MYmind MBI on participant inclusion, program characteristics, mindfulness teachers, and evaluating treatment efficacy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Authors’ Recommendations on the MYmind Family Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI) for Children With ADHD and Parents, Based on Qualitative Results.

| Participant inclusion and preparation prior to MBI |

| • Develop a screening to evaluate if child-behavior is too disruptive for a group-training |

| • Be cautious regarding inclusion of 8/9-year old children (e.g., consider intellect, reading abilities, self-reflection, motivation) |

| • If pharmacotherapy for child-ADHD is indicated, consider providing MBI after medication is regulated |

| • Carefully discuss time investment and expectations with parents |

| • Consider a less demanding program for parents with high burden |

| The MYmind program |

| • Increase sharing time for parents during or outside the sessions |

| • Reduce duration (<1.5 hr) of child sessions or increase number of breaks (>1) |

| • Carefully monitor possible adverse effects from the homework reward system |

| • Consider follow-up sessions for parents and children to facilitate persistence in practice |

| Mindfulness teachers |

| • Strive for expertise in both mindfulness and behavioral training techniques, and experience with children with externalizing disorders for the child groups • Expertise with adult psychiatric problems is preferable for the parent groups |

| Evaluating treatment efficacy |

| • Consider outcomes for children and parents like parent–child relationship, family climate, acceptance, psychological symptoms, functioning, well-being, and sleep • Consider additional analyses (e.g., comparing the proportions of participants that show meaningful change [Jacobson & Truax, 1991]) on top of mean-based analyses |

Strengths and Limitations

This study described an extensive qualitative analysis in accordance with COREQ. With the purposive sample we aimed to take into account the heterogeneity of the ADHD population, for example considering age, IQ, ethnicity, ADHD-medication use, and comorbidity. However, only one parent that stopped with the MBI consented with an interview, which may have resulted in underreported barriers and adverse effects. A strength is that the interviews were conducted individually at a location chosen by the participants, where they felt at ease (mostly their home). Multiple perspectives were included, from parents, children, and mindfulness teachers. The addition of the perspective of a more distant and objective “observer” (e.g., the schoolteacher, clinician, or researcher) would be valuable. An inherent characteristic of qualitative data analysis is that coding and categorization in themes involves researchers’ interpretation. To limit the subjectivity, this was done by multiple researchers with extensive discussion. Further, we were aware of possible confirmation bias working with authors who are involved in MBI development (AS, SB) but also researchers who are not (CG, JB). Future studies could consider interviewing at different points in time following MBI, allowing detection of the kind of perceived effects that increase or only emerge after a longer period of time (Bowen et al., 2014). Further, specifically interviewing participants that discontinue the intervention could help to increase our understanding of possible adverse effects (Mitchell et al., 2018).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_material for Mindfulness for Children With ADHD and Mindful Parenting (MindChamp): A Qualitative Study on Feasibility and Effects by Nienke M. Siebelink, Shireen P. T. Kaijadoe, Fylis M. van Horssen, Josanne N. P. Holtland, Susan M. Bögels, Jan K. Buitelaar, Anne E. M. Speckens and Corina U. Greven in Journal of Attention Disorders

Author Biographies

Nienke M. Siebelink, MSc, is a PhD student at the Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen.

Shireen P. T. Kaijadoe, BSc, is Project Manager Innovation and qualitative researcher at Karakter Child and Adolescent Psychiatry University Center, Nijmegen.

Fylis M. van Horssen, BSc, is a master student in Biomedical Sciences at the Radboud University, Nijmegen.

Josanne N. P. Holtland, BSc, is a master student in Clinical Child and Youth Psychology at the University of Tilburg.

Susan M. Bögels, PhD, is a psychotherapist and professor in Family Mental Health and Mindfulness at the Department of Developmental Psychology and Research Institute of Child Development and Education at of the University of Amsterdam. Her main research interests are the intergenerational transmission of anxiety and MBIs.

Jan K. Buitelaar, MD, is a professor of psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry at the Radboud University Medical Center, and at the Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition, and Behaviour, Nijmegen. He has a long-standing clinical and research interest in neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD and ADHD.

Anne E. M. Speckens, MD, is a professor of psychiatry and founder and scientific director of the Center for Mindfulness at the Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen. The research interests of AS focus on effectiveness and working mechanisms of mindfulness in patients with both psychiatric and somatic conditions and in health care professionals.

Corina U. Greven, PhD, is an associate professor at the Radboud University Medical Center, and at the Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition, and Behaviour, Nijmegen. Her research focuses on behavioral genetics of ADHD, MBI for ADHD, and sensory processing sensitivity.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: JB has been in the past 3 years a consultant to/member of advisory board of/and/or speaker for Takeda/Shire, Roche, Janssen, Medice, Angelini, and Servier. He is not an employee of any of these companies, and not a stock shareholder of any of these companies. He has no other financial or material support, including expert testimony, patents, royalties. SB is shareholder of UvA minds, in which MYmind is offered to families, provides teacher training in MYmind to professionals, and is the author of the MYmind guide for professionals and MYmind workbook for youth and parents. AS is the founder and clinical director of the Radboudumc Center for Mindfulness. The other authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: MindChamp is funded by a Horizon 2020 Marie Sklodowska-Curie Innovative Training Networks grant (CG, JB, grant number 643051 MiND) and MIND Netherlands (CG, JB, AS, SB, grant number 2016 7057), with additional support from the Karakter Child and Adolescent Psychiatry University Center.

ORCID iD: Nienke M. Siebelink  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4710-1071

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4710-1071

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Allan C., Chacko A. (2018). Adverse events in behavioral parent training for children with ADHD: An under-appreciated phenomenon. The ADHD Report, 26(1), 4–9. 10.1521/adhd.2018.26.1.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Boeije H. (2016). Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek (2nd ed.). Boom uitgevers. [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S., Hoogstad B., van Dun L., de Schutter S., Restifo K. (2008). Mindfulness training for adolescents with externalizing disorders and their parents. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(2), 193–209. 10.1017/S1352465808004190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S. M. (2020). MYmind. Mindfulness voor kinderen en jongeren met ADHD en hun ouders. Trainershandleiding. [MYmind. Mindfulness for youth with ADHD, and their parents: A guide for practitioners]. Amsterdam: Lannoo Campus. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S., Witkiewitz K., Clifasefi S. L., Grow J., Chawla N., Hsu S. H., Carroll H. A., Harrop E., Collins S. E., Lustyk M. K., Larimer M. E. (2014). Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(5), 547–556. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf V., Szabo M., Abbott M. J. (2019). The effect of mindfulness interventions for parents on parenting stress and youth psychological outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1336. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairncross M., Miller C. J. (2020). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapies for ADHD: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(5), 627–643. 10.1177/1087054715625301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappe E., Bolduc M., Rouge M. C., Saiag M. C., Delorme R. (2017). Quality of life, psychological characteristics, and adjustment in parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Quality of Life Research, 26(5), 1283–1294. 10.1007/s11136-016-1446-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Compen F. R., Bisseling E. M., Schellekens M. P., Jansen E. T., van der Lee M. L., Speckens A. E. (2017). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for cancer patients delivered via Internet: Qualitative study of patient and therapist barriers and facilitators. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(12), e407. 10.2196/jmir.7783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deault L. C. (2010). A systematic review of parenting in relation to the development of comorbidities and functional impairments in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41(2), 168–192. 10.1007/s10578-009-0159-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan L. G., Coatsworth J. D., Greenberg M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270. 10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning D. L., Griffiths K., Kuyken W., Crane C., Foulkes L., Parker J., Dalgleish T. (2019). Research review: The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents—A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 60(3), 244–258. 10.1111/jcpp.12980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein J. N., Weiss M. D. (2012). Assessing treatment outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a narrative review. Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 14(6), PCC.11r01336. 10.4088/PCC.11r01336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S., Ling M., Hill B., Rinehart N., Austin D., Sciberras E. (2018. a). Systematic review of meditation-based interventions for children with ADHD. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(1), 9–27. 10.1007/s00787-017-1008-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S. W., Owens J. S., Wymbs B. T., Ray A. R. (2018. b). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 157–198. 10.1080/15374416.2017.1390757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone S. V., Asherson P., Banaschewski T., Biederman J., Buitelaar J. K., Ramos-Quiroga J. A., Rohde L. A., Sonuga-Barke E. J. S., Tannock R., Franke B. (2015). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 1, 15020. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G., Strauss A. L. (2008). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research (3rd ed.). Aldine Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Annandale E., Ashcroft R., Barlow J., Black N., Bleakley A., Boaden R., Braithwaite J., Britten N., Carnevale F., Checkland K., Cheek J., Clark A., Cohn S., Coulehan J., Crabtree B., Cummins S., Davidoff F., Davies H., . . . Ziebland S. (2016). An open letter to The BMJ editors on qualitative research. British Medical Journal, 352, i563. 10.1136/bmj.i563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkaart-van Roijen L., Zwirs B. W. C., Bouwmans C., Tan S. S., Schulpen T. W. J., Vlasveld L., Buitelaar J. K. (2007). Societal costs and quality of life of children suffering from attention deficient hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 16(5), 316–326. 10.1007/s00787-007-0603-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honggui Z., Hongv L., Yunlong D. (2020). Effects of short-term mindfulness-based training on executive function: Divergent but promising. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. Advance online publication. 10.1002/cpp.2453 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huber M., van Vliet M., Giezenberg M., Winkens B., Heerkens Y., Dagnelie P. C., Knottnerus J. A. (2016). Towards a “patient-centred” operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open, 6(1), e010091. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N. S., Truax P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. Piatkus. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. 10.1093/clipsy/bpg016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (2011). Some reflections on the origins of MBSR, skillful means, and the trouble with maps. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(1), 281–306. 10.1080/14639947.2011.564844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham J. J., Gargon E., Clarke M., Williamson P. R. (2013). Can a core outcome set improve the quality of systematic reviews?—A survey of the Co-ordinating Editors of Cochrane review groups. Trials, 14(1), 21. 10.1186/1745-6215-14-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo H. H. M., Wong S. W. L., Wong J. Y. H., Yeung J. W. K., Snel E., Wong S. Y. S. (2020). The effects of family-based mindfulness intervention on ADHD symptomology in young children and their parents: A randomized control trial. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(5), 667–680. 10.1177/1087054717743330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson K. E., Kerr S., McGee E., Morgan A., Cheater F. M., McLean J., Egan J. (2014). The association between social capital and mental health and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: An integrative systematic review. BMC Psychology, 2(1), 7. 10.1186/2050-7283-2-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J., Bates A., Zylowska L. (2018). Adverse events in mindfulness-based interventions for ADHD. The ADHD Report, 26(2), 15–18. 10.1521/adhd.2018.26.2.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molina B. S., Hinshaw S. P., Swanson J. M., Arnold L. E., Vitiello B., Jensen P. S., Epstein J. N., Hoza B., Hechtman L., Abikoff H. B., Elliott G. R., Greenhill L. L., Newcorn J. H., Wells K. C., Wigal T., Gibbons R. D., Hur K., Houck P. R., & MTA Cooperative Group. (2009). The MTA at 8 years: Prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(5), 484–500. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilha S. C. O. S., Virtuoso S., Tonin F. S., Borba H. H. L., Pontarolo R. (2018). Efficacy and safety of drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: A network meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(10), 1335–1345. 10.1007/s00787-018-1125-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen P. D., Storebo O. J., Shmueli-Goetz Y., Bojesen A. B., Simonsen E., Bilenberg N. (2018). Childhood ADHD and treatment outcome: The role of maternal functioning. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 12, 31. 10.1186/s13034-018-0234-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof A., Bruin E., Blom R. N., Singh N., Bögels S. (2019). Mindfulness-based program for autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative study of the experiences of children and parents. Mindfulness, 10, 1936–1951. 10.1007/s12671-019-01202-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruuskanen E., Leitch S., Sciberras E., Evans S. (2019). “Eat, pray, love. Ritalin”: A qualitative investigation into the perceived barriers and enablers to parents of children with ADHD undertaking a mindful parenting intervention. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 37, 39–46. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick J. A., Merwood A., Asherson P. (2019). The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11(3), 241–253. 10.1007/s12402-018-0277-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebelink N. M., Bögels S. M., Boerboom L. M., de Waal N., Buitelaar J. K., Speckens A. E., Greven C. U. (2018). Mindfulness for children with ADHD and mindful parenting (MindChamp): Protocol of a randomised controlled trial comparing a family mindfulness-based intervention as an add-on to care-as-usual with care-as-usual only. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 237. 10.1186/s12888-018-1811-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y. Y., Holzel B. K., Posner M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225. 10.1038/nrn3916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taren A. A., Gianaros P. J., Greco C. M., Lindsay E. K., Fairgrieve A., Brown K. W., Rosen R. K., Ferris J. L., Julson E., Marsland A. L., Creswell J. D. (2017). Mindfulness meditation training and executive control network resting state functional connectivity: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine, 79(6), 674–683. 10.1097/psy.0000000000000466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UK Network for Mindfulness-Based Teachers. (2011). Good Practice Guidelines for Teaching Mindfulness-Based Courses. https://bamba.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/GPG-for-Teaching-Mindfulness-Based-Courses-BAMBA.pdf

- Van Dam N. T., van Vugt M. K., Vago D. R., Schmalzl L., Saron C. D., Olendzki A., Meissner T., Lazar S. W., Kerr C. E., Gorchov J., Fox K. C. R., Field B. A., Britton W. B., Brefczynski-Lewis J. A., Meyer D. E. (2018). Mind the hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 36–61. 10.1177/1745691617709589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Weijer-Bergsma E., Formsma A. R., de Bruin E. I., Bögels S. M. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training on behavioral problems and attentional functioning in adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(5), 775–787. 10.1007/s10826-011-9531-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Oord S., Bögels S. M., Peijnenburg D. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(1), 139–147. 10.1007/s10826-011-9457-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielgosz J., Goldberg S. B., Kral T. R. A., Dunne J. D., Davidson R. J. (2019). Mindfulness meditation and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15(1), 285–316. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Chan S. K. C., Lo H. H. M., Chan C. Y. H., Chan J. C. Y., Ting K. T., Gao T. T., Lai K. Y. C., Bögels S. M., Wong S. Y. S. (2017). Mindfulness-based intervention for Chinese children with ADHD and their parents: A pilot mixed-method study. Mindfulness, 8, 859–872. 10.1007/s12671-016-0660-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Diaz-Roman A., Cortese S. (2018). Meditation-based therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 21(3), 87–94. 10.1136/ebmental-2018-300015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_material for Mindfulness for Children With ADHD and Mindful Parenting (MindChamp): A Qualitative Study on Feasibility and Effects by Nienke M. Siebelink, Shireen P. T. Kaijadoe, Fylis M. van Horssen, Josanne N. P. Holtland, Susan M. Bögels, Jan K. Buitelaar, Anne E. M. Speckens and Corina U. Greven in Journal of Attention Disorders