Abstract

Background

This study aimed to investigate the incidence and long-term survival outcomes of occult lung cancer between 2004 and 2015.

Methods

A total of 2958 patients were diagnosed with occult lung cancer in the 305,054 patients with lung cancer. The entire cohort was used to calculate the crude incidence rate. Eligible 52,472 patients (T1-xN0M0, including 2353 occult lung cancers) were selected from the entire cohort to perform survival analyses after translating T classification according to the 8th TNM staging system. Cancer-specific survival curves for different T classifications were presented.

Results

The crude incidence rate of occult lung cancer was 1.00 per 100 patients, and it was reduced between 2004 and 2015 [1.4 per 100 persons in 2004; 0.6 per 100 persons in 2015; adjusted risk ratio = 0.437, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.363–0.527]. In the survival analysis, there were 2206 death events in the 2353 occult lung cancers. The results of the multivariable analysis revealed that the prognoses with occult lung cancer were similar to patients with stage T3N0M0 (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.054, 95% CI 0.986–1.127, p = 0.121). Adjusted survival curves presented the same results. In addition, adjusted for other confounders, female, age ≤ 72 years, surgical treatment, radiotherapy, adenocarcinoma, and non-squamous and non-adenocarcinoma non-small cell carcinoma were independent protective prognostic factors (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Occult lung cancer was uncommon. However, the cancer-specific survival of occult lung cancer was poor, therefore, we should put the assessment of its prognoses on the agenda. Timely surgical treatment and radiotherapy could improve survival outcomes for those patients. Besides, we still need more research to confirm those findings.

Keywords: Occult lung cancer, Incidence, Survival, Surveillance, Epidemiology, And end results database

Background

Lung cancer still is the leading malignancy in the global cancer spectrum of morbidity and mortality [1]. Lung cancer mainly comprises non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC), with more than 83% of all cases being NSCLC [2]. Because of late diagnosis and tumor recurrence, the 5-year overall survival rate of patients with NSCLC and SCLC remains low (approximately 23 and 6%, respectively) [2, 3]. Tumor proven by the presence of malignant cells in sputum or bronchial washings but not visualized by imaging or bronchoscopy is considered as occult lung cancer [4, 5]. Previous studies on the incidence of occult lung cancer have only analyzed groups of stroke patients, or incidental case reports of other diseases [6–9]. Therefore, for lung cancer patients, the incidence information of occult lung cancer remains insufficient.

In addition, accurate tumor-lymph node-metastasis (TNM) staging means that the prognosis of the patients is accurate [10, 11]. Patients with stage IA (classification T1N0M0) have the best long-term survival outcomes in all lung cancers [10]. In the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, occult lung cancers are classified as TxN0M0 [12]. Thus, the prognosis of occult lung cancer patients remains unclear because of the unclear TNM classification. The prognoses of diseases have an effect on treatment selection and patients’ management. However, there was no data about the incidence rate and survival analyses of occult lung cancer in the previous studies. Thus, we aimed to investigate the incidence rate and prognostic level of those patients with occult lung cancer.

Methods

Patients

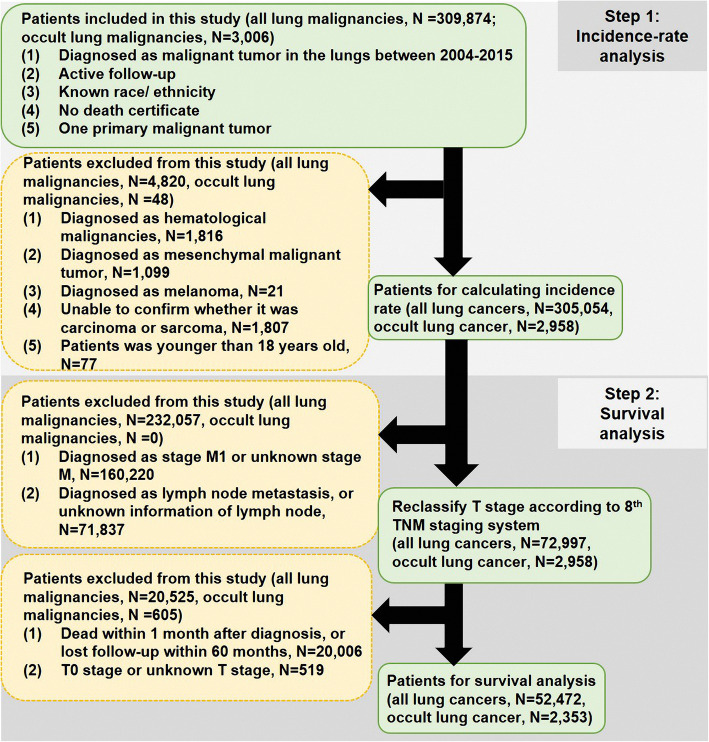

The Ethics Committee of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital approved this study and considered this study exempt from ethical review because existing data without patient identifiers were used. This study majorly included two parts, incidence-rate analysis (step 1) and survival analysis (step 2). We retrospectively recruited patients who were histologically diagnosed with malignant tumor in the lungs as their first primary malignancy from 2004 to 2015 in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which contains clinicopathological and survival data of cancer patients from 18 registries. Therefore, the present study could be considered as a multi-center analysis. The selection criteria of patients were shown in Fig. 1. A total of 305,054 patients (including 2958 occult lung cancers) were used to perform incidence analysis after step-one case selection. Next, we processed step-two case selection. There were 52,472 eligible patients (including 2353 occult lung cancers) for survival analysis. The detailed information was presented as Fig. 1. All patient records were anonymized before analysis. Information collected from the SEER database included sex, race/ ethnicity, survival time, cause on disease, age at diagnosis, tumor size, approach of treatment (including surgical treatment, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy), tumor differentiation, histological subtype, tumor location, TNM stage, and marital status.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of this study

Follow-up

Cancer-specific survival, which was the duration from the date of diagnosis to death caused by lung cancer, was regarded as our observational endpoint. For survival analysis, follow-up duration ranged from 1.0 to 155.0 months, with a median of 27.0 months. Those patients who entered the survival analysis had definitive survival status, death or alive.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistics 25.0 software (IBM SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and GraphPad Prism 8 (https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/). Risk ratios (RRs), hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using multivariable Logistic regression analysis and Cox regression analysis, respectively (regression method was Enter selection). The average value of each covariate was calculated by the multivariable Cox regression model, and estimated the adjusted survival curves of T classification. Statistical tests were considered statistically significant with two-sided p value < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

In the step-one case selection, there were 305,054 patients (including 2958 occult lung cancers) for calculating incidence. Majority of the patients were male (N = 162,448, 53.3%), and 248,125 (81.3%) were non-Hispanic whites. The median age was 68 years old (range from 18 years to 104 years). The detailed information of patient characteristics was shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristic of lung cancer patients from Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database

|

All patients (N = 305,054) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 162,448 | 53.3 |

| Female | 142,606 | 46.7 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic whites | 248,125 | 81.3 |

| Non-Hispanic others | 56,929 | 18.7 |

| Age (year) | ||

| ≤ 68 | 159,281 | 52.2 |

| > 68 | 145,773 | 47.8 |

| Median (range) | 68 (18–104) | |

| z Grade | ||

| Well | 16,073 | 5.3 |

| Moderate | 52,350 | 17.2 |

| Poor | 85,221 | 27.9 |

| Undifferentiated | 14,184 | 4.6 |

| Unknown | 13,7226 | 45.0 |

| Tumor Location | ||

| Main bronchus | 15,819 | 5.2 |

| Upper lobe | 155,796 | 51.1 |

| Middle lobe | 13,314 | 4.4 |

| Lower lobe | 77,101 | 25.3 |

| Overlapping lesion of lung | 3973 | 1.2 |

| Unknown | 39,051 | 12.8 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| No | 174,025 | 57.0 |

| Yes | 128,452 | 42.2 |

| Unknown | 2577 | 0.8 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No | 159,187 | 52.2 |

| Yes | 145,867 | 47.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 156,432 | 51.3 |

| Non-married | 136,241 | 44.6 |

| Unknown | 12,381 | 4.1 |

| Surgical treatment | ||

| None | 233,739 | 76.5 |

| Limited resection | 14,070 | 4.6 |

| Lobectomy | 51,453 | 16.8 |

| Pneumonectomy | 4030 | 1.4 |

| Unknown surgical approach | 729 | 0.2 |

| Unknown | 1543 | 0.5 |

| Year at diagnosis | ||

| 2004 | 23,625 | 7.7 |

| 2005 | 22,774 | 7.6 |

| 2006 | 24,250 | 7.9 |

| 2007 | 25,094 | 8.2 |

| 2008 | 25,384 | 8.3 |

| 2009 | 25,936 | 8.5 |

| 2010 | 25,606 | 8.4 |

| 2011 | 25,631 | 8.4 |

| 2012 | 26,120 | 8.6 |

| 2013 | 26,344 | 8.6 |

| 2014 | 26,874 | 8.8 |

| 2015 | 27,416 | 9.0 |

| Occult lung cancer | ||

| Yes | 2958 | 1.0 |

| No | 302,096 | 99.0 |

After step-two case selection, eligible 52,472 patients (including 2353 occult lung cancers) entered into processing of survival analysis. Male patients accounted for 51.2% (N = 26,858). Age at diagnosis ranged from 18 years old to 100 years old (median 70 years). The major part of histological subtypes belonged to adenocarcinoma (N = 23,406, 44.6%) as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological characteristic of lung cancer patients for survival analysis

|

All patients (N = 52,472) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 26,858 | 51.2 |

| Female | 25,614 | 48.8 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic whites | 43,818 | 83.5 |

| Non-Hispanic others | 8654 | 16.5 |

| Age (year) | ||

| ≤ 68 | 23,070 | 44.0 |

| > 68 | 29,402 | 56.0 |

| Median (range) | 70 (18–100) | |

| Grade | ||

| Well | 5579 | 10.6 |

| Moderate | 16,142 | 30.8 |

| Poor | 16,855 | 32.1 |

| Undifferentiated | 1745 | 3.3 |

| Unknown | 12,151 | 23.2 |

| Tumor Location | ||

| Main bronchus | 1271 | 2.4 |

| Upper lobe | 30,463 | 58.0 |

| Middle lobe | 2423 | 4.6 |

| Lower lobe | 15,734 | 30.0 |

| Overlapping lesion of lung | 607 | 1.2 |

| Unknown | 1974 | 3.8 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| No | 37,612 | 71.7 |

| Yes | 14,508 | 27.6 |

| Unknown | 352 | 0.7 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No | 39,127 | 74.6 |

| Yes | 13,345 | 25.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 27,089 | 51.6 |

| Non-married | 23,504 | 44.8 |

| Unknown | 1879 | 3.6 |

| Surgical treatment | ||

| None | 22,136 | 42.2 |

| Limited resection | 5784 | 11.0 |

| Lobectomy | 23,228 | 44.2 |

| Pneumonectomy | 984 | 1.9 |

| Unknown surgical approach | 29 | 0.1 |

| Unknown | 311 | 0.6 |

| Histological subtypes | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 16,691 | 31.8 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 23,406 | 44.6 |

| Non-squamous and non-adenocarcinoma NSCLC | 5128 | 9.8 |

| Small-cell carcinoma | 2583 | 4.9 |

| Unknown non-sarcoma carcinoma | 477 | 0.9 |

| Unknown NSCLC | 4187 | 8.0 |

| T classification | ||

| T1a | 1752 | 3.3 |

| T1b | 9439 | 18.0 |

| T1c | 8412 | 16.1 |

| T2a | 11,509 | 21.9 |

| T2b | 3784 | 7.2 |

| T3 | 4180 | 8.0 |

| T4 | 11,043 | 21.0 |

| Tx (occult) | 2353 | 4.5 |

NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer

Incidence-rate analysis

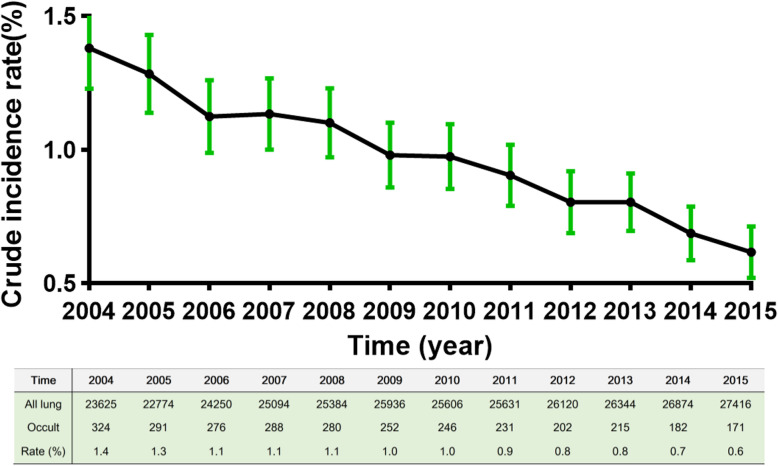

In the all 305,054 patients, the crude incidence rate was 1.00 per 100 patients, and it was reduced between 2004 and 2015 [Fig. 2, 1.4 (95% CI 1.22–1.52) per 100 persons in 2004; 0.6 (95% CI 0.53–0.72) per 100 persons in 2015; Table 3, adjusted RR = 0.437, 95% CI 0.363–0.527]. The results of Linear regression revealed that trends about crude incidence rate of occult lung cancer was decreased over time (R = ˗0.023, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

The crude incidence rate of occult lung cancer over time in the 305,054 lung cancer patients

Table 3.

The results of multivariable Logistic regression analyses

| Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | P-Value | |

| Year at diagnosis | |||

| 2004 | 1 | reference | |

| 2005 | 0.927 | 0.790–1.087 | 0.349 |

| 2006 | 0.828 | 0.705–0.974 | 0.022 |

| 2007 | 0.828 | 0.706–0.972 | 0.021 |

| 2008 | 0.792 | 0.674–0.930 | 0.005 |

| 2009 | 0.696 | 0.589–0.821 | < 0.001 |

| 2010 | 0.685 | 0.580–0.809 | < 0.001 |

| 2011 | 0.643 | 0.543–0.762 | < 0.001 |

| 2012 | 0.549 | 0.460–0.655 | < 0.001 |

| 2013 | 0.578 | 0.486–0.687 | < 0.001 |

| 2014 | 0.479 | 0.399–0.575 | < 0.001 |

| 2015 | 0.437 | 0.363–0.527 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 | reference | |

| Female | 0.988 | 0.919–1.063 | 0.752 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.035 | 1.031–1.038 | < 0.001 |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic whites | 1 | reference | |

| Non-Hispanic others | 0.925 | 0.842–1.016 | 0.102 |

RR risk ratio, CI confidence interval

Logistic regression’s method was Enter selection

The results of multivariable analysis were adjusted for other confounding factors, such as sex, age, and race/ ethnicity

Survival analysis of T classification

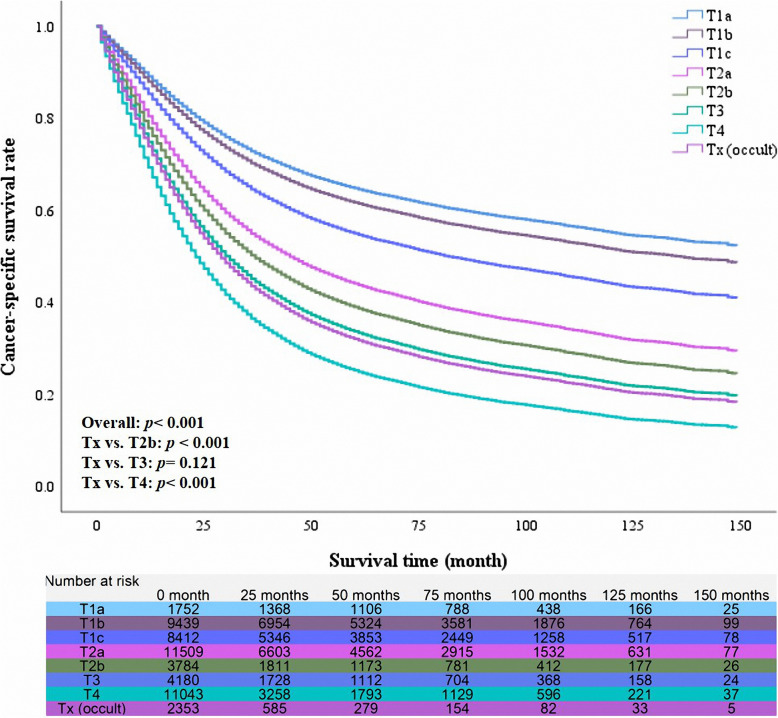

The median survival time of all 52,472 patients was 27 months (range from 1 month to 155 months). Besides, the 1-year, 3-year and 5-year cancer-specific survival rate of this cohort were 62, 49, and 44%, respectively. The unadjusted 5-year cancer-specific survival rate was the best in the patients with T1a (75%) and the worst in the patients with Tx (15%). The median survival time was 13 months (95% CI 12.10–13.90 months) in the patients with Tx, which indicated the rate of death events had exceeded 50%. We also found that the classification of Tx was the riskiest factor for the prognoses (Table 4, unadjusted HR =6.339, p < 0.001). However, the results were not inconsistent after multivariable Cox regression analysis. We used multivariable Cox regression analysis to identify the prognostic role of Tx (occult lung cancer) in the different T classifications (Table 4). After adjusting for other confounders, patients with Tx had a poorer prognosis than patients of T2b (adjusted HR 1.186, p < 0.001), nevertheless better long-term survival outcomes than patients with T4 (adjusted HR 0.845, p < 0.001). Besides, the prognosis for patients of Tx was not statistically different from that of T3 patients (p = 0.121). The adjusted survival curves also presented similar results (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses for prognostic factors

| N | 5-year CSS | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P-Value | HR | 95% CI | P-Value | |||

| T classification | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| T1a | 1752 | 75% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| T1b | 9439 | 67% | 1.230 | < 0.001 | 1.113 | 1.010–1.227 | 0.030 |

| T1c | 8412 | 56% | 1.788 | < 0.001 | 1.379 | 1.252–1.519 | < 0.001 |

| T2a | 11,509 | 47% | 2.345 | < 0.001 | 1.889 | 1.719–2.076 | < 0.001 |

| T2b | 3784 | 37% | 3.079 | < 0.001 | 2.172 | 1.964–2.402 | < 0.001 |

| T3 | 4180 | 31% | 3.759 | < 0.001 | 2.510 | 2.273–2.772 | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 11,043 | 19% | 5.555 | < 0.001 | 3.178 | 2.892–3.493 | < 0.001 |

| Tx (occult) | 2353 | 15% | 6.344 | < 0.001 | 2.624 | 2.365–2.910 | < 0.001 |

| Subgroup comparison | |||||||

| Tx vs. T2b | – | – | 2.020 | < 0.001 | 1.186 | 1.104–1.273 | < 0.001 |

| Tx vs. T3 | – | – | 1.648 | < 0.001 | 1.054 | 0.986–1.127 | 0.121 |

| Tx vs. T4 | – | – | 1.127 | < 0.001 | 0.845 | 0.801–0.891 | < 0.001 |

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

Cox regression’s method was Enter selection

The results of multivariable analysis were adjusted for other confounding factors, such as sex, age, tumor differentiation, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, surgical treatment, histological subtypes, marital status, tumor location and race/ ethnicity

Fig. 3.

The adjusted survival curves of different T classifications

Prognostic analysis for occult lung cancer

There were 2353 occult lung cancer patients for survival analyses, of which baseline characteristics were shown in Table 5. In this cohort, there were 2206 death events in the 2353 occult lung cancers. Female patients showed a better survival than male patients (Table 6, adjusted HR = 0.796, 95%CI 0.726–0.876, p < 0.001). Besides, the prognosis in patients with age > 72 years was poorer than younger patients (adjusted HR = 1.183, 95%CI 1.063–1.295). The number of adenocarcinomas was the most, which accounted for 33.0% (N = 776). Its long-term survival outcomes were better than squamous cell carcinomas (adjusted HR = 0.878, p = 0.042). Of note, 1162 patients didn’t receive any treatment. However, patients who underwent surgical resection or radiotherapy had improved survival benefits (Table 6). One-hundred and twenty-six patients underwent lobectomy, whose 5-year cancer-specific survival rate reached 47%. After adjusting for other confounders, we identified sex, tumor differentiation, tumor location, age, histological subtypes, radiotherapy, and surgical treatment as independent prognostic factors.

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics in the cohort with occult lung cancer

| Variables | All patients (N = 2353) |

Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1235 | 52.5 |

| Female | 1118 | 47.5 |

| Tumor differentiation | ||

| Well | 186 | 7.9 |

| Moderate | 409 | 17.4 |

| Poor | 686 | 29.1 |

| Unknown | 1072 | 45.6 |

| Tumor location | ||

| Upper lobe | 1096 | 46.6 |

| Middle lobe | 105 | 4.5 |

| Lower lobe | 668 | 28.4 |

| Other location | 105 | 4.5 |

| Unknown | 379 | 16.0 |

| Age (year) | ||

| ≤ 72 | 1210 | 51.4 |

| > 72 | 1143 | 48.6 |

| Median (range) | 72 (19–99) | |

| Histological subtypes | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 726 | 30.9 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 776 | 33.0 |

| Non-squamous and non-adenocarcinoma NSCLC | 165 | 7.0 |

| Small-cell carcinoma | 300 | 12.7 |

| Unknown non-sarcoma carcinoma | 55 | 2.3 |

| Unknown NSCLC | 331 | 14.1 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| No | 1677 | 71.3 |

| Yes | 676 | 28.7 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| No | 1703 | 72.4 |

| Yes | 623 | 26.5 |

| Unknown | 27 | 1.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1092 | 46.4 |

| Non-married | 1116 | 47.4 |

| Unknown | 145 | 6.2 |

| Race/ ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic whites | 1928 | 81.9 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 425 | 18.1 |

| Surgical treatment | ||

| None | 2077 | 88.3 |

| Limited resection | 77 | 3.3 |

| Lobectomy | 126 | 5.4 |

| Pneumonectomy | 7 | 0.3 |

| Unknown surgical approach | 4 | 0.2 |

| Unknown | 62 | 2.5 |

NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer

Table 6.

Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analyses for prognostic factors in 2353 occult lung cancer patients

| Variables | 5-year CSS | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P-Value | HR | 95% CI | P-Value | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 14% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| Female | 16% | 0.830 | < 0.001 | 0.796 | 0.723–0.876 | < 0.001 |

| Tumor differentiation | ||||||

| Well | 18% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| Moderate | 17% | 1.062 | 0.564 | 0.654 | 0.769–1.179 | 0.654 |

| Poor | 13% | 1.373 | 0.001 | 1.214 | 1.003–1.506 | 0.046 |

| Unknown | 15% | 1.152 | 0.131 | 1.038 | 0.860–1.264 | 0.669 |

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Upper lobe | 17% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| Middle lobe | 9% | 1.090 | 0.447 | 1.141 | 0.913–1.427 | 0.246 |

| Lower lobe | 14% | 1.110 | 0.067 | 1.124 | 1.004–1.259 | 0.042 |

| Other location | 18% | 1.115 | 0.354 | 1.036 | 0.822–1.305 | 0.767 |

| Unknown | 11% | 1.291 | < 0.001 | 1.241 | 1.084–1.421 | 0.002 |

| Age (median, year) | ||||||

| ≤ 72 | 16% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| > 72 | 14% | 1.237 | < 0.001 | 1.183 | 1.072–1.305 | 0.001 |

| Histological subtypes | ||||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 13% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 14% | 0.890 | 0.05 | 0.878 | 0.775–0.995 | 0.042 |

| Non-squamous and non-adenocarcinoma NSCLC | 24% | 0.680 | < 0.001 | 0.754 | 0.609–0.933 | 0.010 |

| Small-cell carcinoma | 12% | 0.992 | 0.920 | 0.958 | 0.812–1.131 | 0.616 |

| Unknown non-sarcoma carcinoma | 31% | 0.647 | 0.022 | 0.558 | 0.380–0.820 | 0.003 |

| Unknown NSCLC | 15% | 0.952 | 0.518 | 0.923 | 0.790–1.079 | 0.317 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 17% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| Yes | 10% | 0.926 | 0.132 | 0.946 | 0.846–1.059 | 0.338 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||

| No | 15% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| Yes | 16% | 0.795 | < 0.001 | 0.716 | 0.638–0.802 | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 12% | 1.077 | 0.730 | 1.020 | 0.666–1.562 | 0.928 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Non-married | 14% | 1 | ||||

| Married | 15% | 0.990 | 0.837 | |||

| Unknown | 17% | 1.045 | 0.662 | |||

| Race/ ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic whites | 15% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| Non-Hispanic other | 16% | 0.995 | 0.938 | 1.063 | 0.941–1.202 | 0.323 |

| Surgical treatment | ||||||

| None | 12% | 1 | 1 | reference | ||

| Limited resection | 30% | 0.462 | < 0.001 | 0.476 | 0.354–0.640 | < 0.001 |

| Lobectomy | 47% | 0.285 | < 0.001 | 0.269 | 0.269–0.352 | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonectomy | 13% | 0.476 | 0.098 | 0.427 | 0.176–1.032 | 0.059 |

| Unknown surgical approach | NA | 0.506 | 0.238 | 0.544 | 0.175–1.695 | 0.294 |

| Unknown | 16% | 0.972 | 0.847 | 0.899 | 0.673–1.203 | 0.475 |

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, NSCLC non-small cell lung carcinoma

Cox regression’s method was Enter selection

Discussion

In the present study, we used the data of 305,054 patients (including 2958occult lung cancer patients) to perform incidence-rate analysis. The results revealed that the crude incidence rate of occult lung cancer was 1.00 per 100 patients, and the incidence-rate trend over time was likely to be reduced between 2004 and 2015. Next, data on 52,472 eligible patients were analyzed by Cox regression analysis including univariable and multivariable analyses. Those patients included 2353 cases of occult lung cancer. According to the results, we found that occult lung cancer patients didn’t have satisfactory survival outcomes. The prognosis of occult lung cancer was between T2b’s and T4’s. Besides, there was no significant difference in the prognosis of patients with T3 classification or occult lung cancer. After adjusting for other confounders, the female, age ≤ 72, well differentiation, adenocarcinoma, radiotherapy, and surgical resection were considered as independent protective prognostic factors for 2353 occult lung cancer patients. Therefore, we suggested that surgery might be an appropriate option for occult lung cancer.

The incidence rate of occult lung cancer varied to a certain extent in the different populations. Previous studies and case reports found that occult lung cancer was usually accompanied by symptoms, metastatic diseases or other internal-medicine diseases when it was detected [6, 13–16]. Yoel Siegel et al. described a case report that occult lung cancer could mimic pneumonia and a pulmonary embolus by occluding a pulmonary vein [7]. A case by William Carrera et al. presented that occult small cell lung cancer might have a relation with occurring of retinopathy with chorioretinitis and optic neuritis [8]. Besides, Hui Mai et al. performed a study about characteristics of occult lung cancer-associated ischemic stroke, and suggested that occult cancer should be considered in the setting of multiple and recurrent embolic strokes within the short term in the absence of conventional stroke etiologies [9]. The above cases and study showed that occult lung cancer might be accompanied by different clinical symptoms. However, clinicians tend to pay more attention to their specialties, thus the diagnosis of the occult lung cancer becomes more complicated. Therefore, the research on the incidence rate of this disease may provide clinicians with some references for disease diagnosis and treatment.

Because malignant tumors may cause the blood to hypercoagulable state, which leads to the occurrence of thrombosis [17], the previous researchers began to investigate the incidence of occult lung cancer in stroke patients. Alejandro Daniel Babore et al. analyzed data of over 800,000 patients, and uncovered that the prevalence of occult lung cancer was 5.3 per 1000 patients in the stroke patients, and 2.6 per 1000 patients in the control group [6]. The sample size of their study was large, therefore, the results had clinical reference value. However, the results of the present study revealed that crude incidence rate of occult lung cancer was 10.0 per 1000 patients, which was much higher than the findings from above study. This difference in the incidence-rate results between above two studies was likely to be due to different selected cohorts. Our study cohort focused on lung cancer, which led to a higher incidence rate of occult lung cancer in the present study. However, the study by Alejandro Daniel Babore et al. majorly compared the incidence rate of occult lung cancer in stoke patients with that in general patients. Besides, they tried to explore the factors which might have effect on incidence rate. Though, this present study paid more attention to the incidence rate of occult lung cancer in entire lung cancer cohort, and illustrated that the incidence rate over time was reduced between 2004 and 2015. The reason why general trend over time was declined might be the popularization of computed tomography screening and the promotion of bronchoscopy [4, 18, 19].

The present study found that the prognosis of occult lung cancer patients was poorer than that in patients with T2 disease. Those patients might have occult metastasis of lymph node or another organ, which leads to a poor prognosis. Of note, timely therapy could improve the long-term survival in the occult lung cancer. Patients who underwent surgical resection had better cancer-specific survival than patients who didn’t receive surgical treatment. And, the best survival benefit was derived from lobectomy. Joel J. Bechtel et al. and Cortese DA et al. had similar findings in their research [20, 21]. They suggested that 5-year survival rate was 74 and 90% in patients with cure resection, respectively. However, the sample size was relatively small in their research [20, 21]. For example, in the study by Joel J. Bechtel et al., only 27 of the 51 patients they enrolled underwent surgical resection. Similarly, there were only 54 patients underwent operation in the study by Cortese DA et al. The sample size of the present study was different from above mentioned studies causing the difference of 5-year survival rate followed surgical resection. Besides, radiotherapy was proven to have survival benefit in the 71-case study by M Saito et al [22]. In the present study, compared with patients who didn’t receive radiotherapy, cases with radiotherapy had a better survival. These findings confirmed the results from previous study.

This study has several limitations. First, some important information (such as the invasion depth of tumor in the endobronchial wall) wasn’t detailed, as we couldn’t obtain the results of bronchoscopy and radiology in the SEER database. Thus, we did not further categorize the Tx classification. Second, cases with second primary lung cancer were excluded from the study. However, the incidence rate of occult lung cancer might be much higher in the cohort of second primary lung cancer. Therefore, the use of those findings was limited to patients with primary lung cancer. Third, because the data on histological subtypes were not detailed enough, unknown non-sarcoma cancer and unknown non-small cell carcinoma couldn’t be subdivided. Finally, this study belonged to retrospective study. Therefore, more studies are necessary to further explore the incidence rate and prognosis in patients with occult lung cancer.

Conclusions

Occult lung cancer was uncommon. However, the cancer-specific survival of occult lung cancer was poor, therefore, we should put the assessment of its prognoses on the agenda. Timely surgical treatment and radiotherapy could improve survival outcomes. Besides, we still need more research to confirm those findings.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the staff of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results for their contribution in recording medical records. Lei-Lei Wu sincerely thanks Prof. Tie-Hua Rong and Guo-Wei Ma for instructing clinical knowledge, surgery and research in thoracic oncology.

Abbreviations

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- SCLC

Small cell lung cancer

- TNM

Tumor-lymph node-metastasis

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- RR

Risk ratio

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

Authors’ contributions

LLW and DX contributed to the study design, data collection, data analyses, data interpretation, and manuscript drafting. LLW, LHQ and CWL contributed to data analyses and manuscript review. WKL, LLW, LHQ, CWL and DX contributed to data interpretation and manuscript review. All authors contributed to the final approval of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Shanghai Health Commission (2019SY072), Shanghai ShenKang Hospital Development Centre (SHDC22020218), Outstanding Young Medical Talent of Rising Star in Medical Garden of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission "Dong Xie", and Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital Research Fund (FK18001 & FKGG1805). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. The funding bodies played a role in the interpretation of data, in writing, and in reviewing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Any researchers interested in this study could contact corresponding author for requiring data.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital approved this study and considered this study exempt from ethical review because existing data without patient identifiers were used.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lei-Lei Wu and Chong-Wu Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung JJ, Jeng WJ, Hsu WH, Huang BS, Wu YC. Time trends of overall survival and survival after recurrence in completely resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(2):397–405. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823b564a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edell ES, Cortese DA. Bronchoscopic localization and treatment of occult lung cancer. Chest. 1989;96(4):919–921. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petty TL, Tockman MS, Palcic B. Diagnosis of roentgenographically occult lung cancer by sputum cytology. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23(1):59–64. doi: 10.1016/S0272-5231(03)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babore AD, Tybjerg AJ, Andersen KK, Olsen TS. Occult lung cancer manifesting within the first year after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(9):105023. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel Y, Kuker R, Danton G, Gonzalez J. Occult lung Cancer occluding a pulmonary vein with suspected venous infarction, mimicking pneumonia and a pulmonary Embolus. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(2):e11–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrera W, Tsamis KA, Shah R. A case of cancer-associated retinopathy with chorioretinitis and optic neuritis associated with occult small cell lung cancer. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12886-019-1103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mai H, Xia J, Wu Y, Ke J, Li J, Pan J, Chen W, Shao Y, Yang Z, Luo S, Sun Y, Zhao B, Li L. Clinical presentation and imaging characteristics of occult lung cancer associated ischemic stroke. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22(2):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Travis WD, Rusch VW. Lung cancer - major changes in the American joint committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):138–155. doi: 10.3322/caac.21390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu LL. Liu X, Jiang WM, Huang W, Lin P, long H, Zhang LJ, ma GW: stratification of patients with stage IB NSCLC based on the 8th edition of the American joint committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual. Front Oncol. 2020;10:571. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (Version 8.2020, accessed September 15, 2020).

- 13.Navi BB, DeAngelis LM, Segal AZ. Multifocal strokes as the presentation of occult lung cancer. J Neuro-Oncol. 2007;85(3):307–309. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9419-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilardi R, Della Rosa N, Pancaldi G, Landi A. Acrometastasis showing an occult lung cancer. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2013;47(6):550–552. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2012.748319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han YM, Fang LZ, Zhang XH, Yuan SH, Chen JH, Li YM. Polyarthritis as a prewarning sign of occult lung cancer. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2012;28(1):54–56. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2011.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isohata N, Naritaka Y, Shimakawa T, Asaka S, Katsube T, Konno S, et al. Occult lung Cancer incidentally found during surgery for esophageal and gastric Cancer: a case report. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:1841–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dardiotis E, Aloizou AM, Markoula S, Siokas V, Tsarouhas K, Tzanakakis G, Libra M, Kyritsis AP, Brotis AG, Aschner M, Gozes I, Bogdanos DP, Spandidos DA, Mitsias PD, Tsatsakis A. Cancer-associated stroke: pathophysiology, detection and management (review) Int J Oncol. 2019;54(3):779–796. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Heuvelmans MA, Lammers JJ, Weenink C, Yousaf-Khan U, Horeweg N, et al. Reduced lung-Cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutedja TG, Codrington H, Risse EK, Breuer RH, van Mourik JC, Golding RP, Postmus PE. Autofluorescence bronchoscopy improves staging of radiographically occult lung cancer and has an impact on therapeutic strategy. Chest. 2001;120(4):1327–1332. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bechtel JJ, Petty TL, Saccomanno G. Five year survival and later outcome of patients with X-ray occult lung cancer detected by sputum cytology. Lung Cancer. 2000;30(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(00)00190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortese DA, Pairolero PC, Bergstralh EJ, Woolner LB, Uhlenhopp MA, Piehler JM, Sanderson DR, Bernatz PE, Williams DE, Taylor WF, Payne WS, Fontana RS. Roentgenographically occult lung cancer. A ten-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1983;86(3):373–380. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)39149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito M, Yokoyama A, Kurita Y, Uematsu T, Tsukada H, Yamanoi T. Treatment of roentgenographically occult endobronchial carcinoma with external beam radiotherapy and intraluminal low-dose-rate brachytherapy: second report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47(3):673–680. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any researchers interested in this study could contact corresponding author for requiring data.