Abstract

This Campbell systematic review examines the effectiveness of interventions to reduce homelessness and increase residential stability for individuals who are homeless, or at risk of becoming homeless. Forty‐three studies were included in the review, 37 of which are from the USA.

Included interventions perform better than the usual services at reducing homelessness or improving housing stability in all comparisons. These interventions are:

High intensity case management

Housing First

Critical time intervention

Abstinence‐contingent housing

Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing with high intensity case management

Housing vouchers

Residential treatment

These interventions seem to have similar beneficial effects, so it is unclear which of these is best with respect to reducing homelessness and increasing housing stability.

Plain Language Summary

Interventions to reduce homelessness and improve housing stability are effective

There are large numbers of homeless people around the world. Interventions to address homelessness seem to be effective, though better quality evidence is required.

What is this review about?

There are large numbers of homeless people around the world. Recent estimates are over 500,000 people in the USA, 100,000 in Australia and 30,000 in Sweden. Efforts to combat homelessness have been made on national levels as well as at local government levels.

This review assesses the effectiveness of interventions combining housing and case management as a means to reduce homelessness and increase residential stability for individuals who are homeless, or at risk of becoming homeless.

What is the aim of this review?

This Campbell systematic review examines the effectiveness of interventions to reduce homelessness and increase residential stability for individuals who are homeless, or at risk of becoming homeless. Forty‐three studies were included in the review, 37 of which are from the USA.

What studies are included?

Included studies were randomized controlled trials of interventions for individuals who were already, or at‐risk of becoming, homeless, and which measured impact on homelessness or housing stability with follow‐up of at least one year.

A total of 43 studies were included. The majority of the studies (37) were conducted in the United States, with three from the United Kingdom and one each from Australia, Canada, and Denmark.

What are the main findings of this review?

Included interventions perform better than the usual services at reducing homelessness or improving housing stability in all comparisons. These interventions are:

High intensity case management

Housing First

Critical time intervention

Abstinence‐contingent housing

Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing with high intensity case management

Housing vouchers

Residential treatment

These interventions seem to have similar beneficial effects, so it is unclear which of these is best with respect to reducing homelessness and increasing housing stability.

What do the findings of this review mean?

A range of housing programs and case management interventions appear to reduce homelessness and improve housing stability, compared to usual services.

However, there is uncertainty in this finding as most the studies have risk of bias due to poor reporting, lack of blinding, or poor randomization or allocation concealment of participants. In addition to the general need for better conducted and reported studies, there are specific gaps in the research with respect to: 1) disadvantaged youth; 2) abstinence‐contingent housing with case management or day treatment; 3) non‐abstinence contingent housing comparing group vs independent living; 4) Housing First compared to interventions other than usual services, and; 5) studies outside of the USA.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies published up to January 2016. This Campbell systematic review was published in February 2018.

Executive summary

Background

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 25) states that everyone has a right to housing. However, this right is far from being realized for many people worldwide. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are approximately 100 million homeless people worldwide. The aim of this report is to contribute evidence to inform future decision making and practice for preventing and reducing homelessness.

Objectives

To identify, appraise and summarize the evidence on the effectiveness of housing programs and case management to improve housing stability and reduce homelessness among people who are homeless or at‐risk of becoming homeless.

Search methods

We conducted a systematic review in accordance with the Norwegian Knowledge Centre's handbook. We systematically searched for literature in relevant databases and conducted a grey literature search which was last updated in January 2016.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials that included individuals who were already, or at‐risk of becoming, homeless were included if they examined the effectiveness of relevant interventions on homelessness or housing stability. There were no limitations regarding language, country or length of homelessness. Two reviewers screened 2,918 abstracts and titles for inclusion. They read potentially relevant references in full, and included relevant studies in the review.

Data collection and analysis

We pooled the results and conducted meta‐analyses when possible. Our certainty in the primary outcomes was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation for effectiveness approach (GRADE).

Results

We included 43 relevant studies (described in 78 publications) that examined the effectiveness of housing programs and/or case management services on homelessness and/or housing stability. The results are summarized below. Briefly, we found that the included interventions performed better than the usual services in all comparisons. However, certainty in the findings varied from very low to moderate. Most of the studies were assessed as having high risk of bias due to poor reporting, lack of blinding, or poor randomization and/or allocation concealment of participants.

Case management

Case management is a process where clients are assigned case managers who assess, plan and facilitate access to health and social services necessary for the client's recovery. The intensity of these services can vary. One specific model is Critical time intervention, which is based on the same principles, but offered in three three‐month periods that decrease in intensity.

High intensity case management compared to usual services has generally more positive effects: It probably reduces the number of individuals who are homeless after 12‐18 months by almost half (RR=0.59, 95%CI=0.41 to 0.87)(moderate certainty evidence); It may increase the number of people living in stable housing after 12‐18 months and reduce the number of days an individual spends homeless (low certainty evidence), however; it may have no effect on the number of individuals who experience some homelessness during a two year period (low certainty evidence). When compared to low intensity case management, it may have little or no effect on time spent in stable housing (low certainty evidence).

Critical time intervention compared to usual services may 1) have no effect on the number of people who experience homelessness, 2) lead to fewer days spent homeless, 3) lead to more days spent not homeless and, 4) reduce the amount of time it takes to move from shelter to independent housing (low certainty evidence).

Abstinence‐contingent housing programs

Abstinence‐contingent housing is housing provided with the expectation that residents will remain sober. The results showed that abstinence‐contingent housing may lead to fewer days spent homeless, compared with usual services (low certainty evidence).

Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing programs

Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing is housing provided with no expectations regarding sobriety of residents. Housing First is the name of one specific non‐abstinence‐contingent housing program. When compared to usual services Housing First probably reduces the number of days spent homeless (MD=‐62.5, 95%CI=‐86.86 to ‐38.14) and increases the number of days in stable housing (MD=110.1, 95%CI=93.05 to 127.15) (moderate certainty evidence). In addition, it may increase the number of people placed in permanent housing after 20 months (low certainty evidence).

Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing programs (not specified as Housing First) in combination with high intensity case management may reduce homelessness, compared to usual services (low certainty evidence). Group living arrangements may be better than individual apartments at reducing homelessness (low certainty evidence).

Housing vouchers with case management

Housing vouchers is a housing allowance given to certain groups of people who qualify. The results showed that it mayreduce homelessness and improve housing stability, compared with usual services or case management (low certainty evidence).

Residential treatment with case management

Residential treatment is a type of housing offered to clients who also need treatment for mental illness or substance abuse. We found that it mayreduce homelessness and improve housing stability, compared with usual services (low certainty evidence).

Authors’ conclusions

We found that a range of housing programs and case management interventions appear to reduce homelessness and improve housing stability, compared to usual services. The findings showed no indication of housing programs or case management resulting in poorer outcomes for homeless or at‐risk individuals than usual services.

Aside from a general need for better conducted and reported studies, there are specific gaps in the research. We identified research gaps concerning: 1)Disadvantaged youth; 2) Abstinence‐contingent housing with case management or day treatment; 3) Non‐abstinence contingent housing, specifically different living arrangements (group vs independent living); 4) Housing First compared to interventions other than usual services, and; 5) All interventions from contexts other than the USA.

Background

Description of homelessness

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 25) states that everyone has a right to housing. However, this right is far from being realized for many people worldwide. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are approximately 100 million homeless people worldwide (1).

Defining homelessness

The term “homeless” is defined differently according to context, purpose and the geographical setting. There are three basic domains for understanding “home” and “homelessness”: 1) the physical domain (the absence of home); 2) the social domain (homelessness connected to discrimination and social exclusion), and 3) the legal domain (individuals have a right to tenancy, and people without homes still have rights and are deserving of dignity) (2, 3).

In the European Union, four categories of homelessness have been developed: roofless, houseless, insecure housing and inadequate housing (3). In the United States, the Department of Housing and Urban Development defines a person as homeless “if he or she lives in an emergency shelter, transitional housing program (including safe havens), or a place not meant for human habitation, such as a car, abandoned building, or on the streets”(4). For the purpose of this review, the following Norwegian definition of homeless should be considered:

“A person is homeless when s/he lacks a place to live, either rented or owned, and finds themselves in one of the three following situations: Has no place to stay for the night; Is referred to an emergency or temporary shelter/accommodation; Is a ward of the correctional and probation service and due to be released in two months at the latest; Is a resident of an institution and due to be discharged in two months at the latest; Lives with friends, acquaintances or family on a temporary basis” (5).

A glossary of terms related to homelessness, relevant interventions and study characteristics is included in Appendix 1.

Causes of homelessness

In discussing causes of homelessness, it is important to think of two different but related questions: ‘Why does homelessness exist?’ and ‘Who is most vulnerable to becoming homeless?’ (6). As Paul Koegel describes in Homelessness Handbook, the structural context of homelessness (why?) includes “a growing set of pressures that included a dearth of affordable housing, a disappearance of the housing on which the most unstable relied, and a diminished ability to support themselves either through entitlements or conventional or makeshift labour” while the people most affected (who?) “disproportionately include those people least able to compete for housing, especially those vulnerable individuals who had traditionally relied on a type of housing that was at extremely high risk of demolition and conversion…high numbers of people with mental illness and substance abuse…individuals with other sorts of personal vulnerabilities and problems” (6).

Homelessness around the world

Although homelessness has been defined and measured differently, some important descriptive statistics from different countries indicate the importance of the problem. Given the various ways of measuring homelessness, the following statistics are not meant to be compared among each other. A recent report stated that in the USA on a given night in January 2015, almost 565,000 people were experiencing homelessness (sleeping outside, in shelter or in transitional housing) (4). Although homelessness in the USA has decreased by 2% from 2014 to 2015, this figure is still very high (4). Homelessness is also a serious problem in Europe: 34,000 people were defined as homeless in Sweden in 2011 (7), and 14,780 households were defined as unintentionally homeless in the United Kingdom in 2016 (8). In Canada, it is estimated that approximately 1% of the population (35,000) are homeless on any given night (9) and more than 105,000 persons in Australia were counted as homeless on census night in 2011 (10). Little is known about the extent of homelessness in most developing countries due to little or no reliable data (11).

In this review we have included both individuals who are homeless (living on the streets, in shelter or temporary housing), and those who have been identified as at‐risk of becoming homeless (individuals with mental illness, chronic physical illness, substance abuse, recently released criminal offenders).

Description of the intervention

A serious problem, affecting any effort to synthesize research on housing programs and case management for homelessness, is a lack of consistency in the use of program labels (12). Below is a short description of the groups of interventions included in this review.

Case management

Case management (CM) is a “collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual's health and social needs through communication and available resources” (13). In an early review of case management, Morse (1998) summarized the research on why case management has been widely implemented with homeless individuals (14): people who are homeless have multiple serious problems and their service needs are often unmet (15, 16), and these services, and the necessary resources, are difficult to access (17). Furthermore, patients with a mental illness may refuse help and/or miss appointments and/or show aggressive or antisocial behaviour which leads to exclusion from care in many instances (16). Case managers are intended to help guide the individual through the system and facilitate their access to resources and services.

Morse (14)suggested that case management can be described in terms of seven process variables that impact on the intensity of care provided:

-

1.

Duration of services (varying from brief or time limited to ongoing and open‐ended)

-

2.

Intensity of services (involving frequency of client contact, and client‐staff ratios)

-

3.

Focus of services (from narrow and targeted to comprehensive)

-

4.

Resource responsibility (from system gatekeeper responsible for limiting service utilization to client advocate responsible for increasing access or utilization of services)

-

5.

Availability (from scheduled office hours to 24‐hour availability)

-

6.

Location of services (from all services delivered in office to all delivered in vivo)

-

7.

Staffing ratios and composition (from individual caseloads to interdisciplinary teams with shared caseloads)

Case management interventions can be categorized into the following five models: broker case management (BCM), standard case management (SCM), intensive case management (ICM), assertive community treatment (ACT), and critical time intervention (CTI). See Table 3.1 in Appendix 3 for an adapted overview of case management models (14, 18).

In this review, we have organized case management according to intensity: high versus low. The following is a description of the interventions included under high intensity case management:

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) is an example of intensive case management in which a high level of care is provided. The distinguishing features of ACT are described as follows:

“case management provided by a multidisciplinary team of professionals, including psychiatrists, social workers, nurses, occupational therapists, vocational specialists, etc.; 24‐hour, 7 days a week coverage; assertive outreach; and providing support to clients in the community where they live rather than office‐based practice” (19).

Intensive case management (ICM) is similar to ACT. However, the primary difference (McHugo et al., 2004; Meyer and Morrissey, 2007) is that while ACT involves a shared caseload approach, ICM case managers are responsible for their individual caseloads. Furthermore, each staff member of an ACT team provides direct services, while this is not the case when ICM is applied. Finally, ICM usually lacks a validated model including a manual for treatment fidelity. We will use the term intensive case management when referring to both categories (ICM and ACT). When it is necessary to separate the two alternatives, this is explicitly emphasized in the text.

Intensive case management (ICM and ACT) is intended to make sure that the client receives sufficient service, support and treatment when and where it is needed. In this way intensive case management (one case manager per 15 or fewer clients, available 24‐7, and the combined competence of a multidisciplinary team), may help homeless people to obtain accommodation, and once housed avoid eviction.

Low intensity case management refers to all other types of case management where 1) the case manager has responsibility for more than approximately 15 clients, is less available, and where meetings are scheduled less frequently than, for example, once per week, 2) the intervention is described as standard or broker case management, or 3) where intensity was not described.

Housing programs

Housing programs for homeless people typically provide accommodation and include goals such as long term residential stability, improved life‐skills and greater self‐determination (20, 21). These programs are complex and may include various forms of support and services, such as case management, work therapy, treatment of mental illness and substance abuse (22).

The objective, to find accommodation and avoid eviction, is assumed to be facilitated by combining case management with housing programs. The housing programs are more or less based on housing philosophies. The philosophy may determine the sequence of how specific program elements are introduced and removed. The intended endpoint is usually the same, i.e., independent living with as high degree of normality as possible, e.g., apartments owned or rented by the client, integrated among apartments for ordinary tenants, where housing is neither contingent on sobriety nor on treatment compliance, and with no on‐site staff (23).

Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing programs

According to one philosophy, stable and independent housing is needed for the client to become treatment ready(24). Housing should neither be contingent on sobriety nor on treatment compliance, but only on rules that apply for ordinary tenants(24). These housing programs aim to provide a safe and predictable living arrangementin order to make the clients treatment ready. The client's freedom to choose is crucial for treatment to be successful(25). Therefore, housing programs are neither contingent on treatment compliance nor on sobriety. In other words, housing is parallel to and not integrated with treatment, or with other services. This type of treatment is also sometimes referred to as Parallel housing, or Housing First.

“Housing First” is a specific model of non‐abstinence‐contingent housing developed by Pathways to Housing. The program is founded on the idea that housing is a basic right. The two core foundations of the program include psychiatric rehabilitation and consumer choice. Individuals are encouraged to define their own needs and goals. Housing is provided immediately by the program if the individual wishes, and there are no contingencies related to treatment or sobriety. The individual is also offered treatment, in the form of an adapted version of Assertive Community treatment (addition of a nurse practitioner to address physical health problems, and a housing specialist)(24).

Abstinence‐contingent housing programs

An alternative philosophy assumes that clients need a transitional period of sobriety and treatment compliance, before they can live independently in their own apartments. Without the transitional phase they will soon become evicted, and return to homelessness. In other words, this phase may be necessary for many clients to become housing ready. According to this philosophy housing is integrated with treatment. This approach has been referred to as treatment first, continuum of care, and or linear approach(22, 26).

Housing vouchers

Housing vouchers are financial support (usually) from the government where the individual can choose any free market rental property they wish, with no conditions based on tenancy other than financial contribution of 30% of their income(27).

Housing programs and case management

Housing programs and case management tend to appear in various combinations. Evaluations are typically based on comparison of one type of combination with another, or with “usual care” (often drop in centres, after care services, outpatient clinics, brokered case management, etc.). This means that housing programs are often not implemented and evaluated in similar forms. Any effort to analyse and synthesize evaluations of housings programs, case management and other included services, must therefore consider this complexity and lack of clarity. In addition to this complexity, the population of homeless people consists of subgroups that may respond differently to alternative interventions: mentally ill, substance abusers, veterans, women, etc., and each of these subgroups can be divided further.

In order to make the intervention complexity more comprehensible, two dimensions are outlined: (1) case management care intensity, and (2) contingency of tenancy in housing programs. On the one end of the case management scale there are teams with caseloads of maximum 15 clients per case manager, and full on‐site availability (24 hours, 7 days a week) for services and support. In the middle there is CM with caseloads with between 15 to 40 clients per case manager, and service and support only available duringoffice hours at the office. At the other end of the scale there are no case managers, and clients have to rely on drop‐in centres, outpatient clinics, after care services, charities, etc. With respect to contingency in housing programs, there appears to be a dichotomy where programs either require that individuals adhere to agreed‐upon treatment or sobriety obligations in order to remain in housing (abstinence‐contingent) or no conditionality is placed on tenancy, other than in some cases of financial contributions (non‐abstinence‐contingent).

How the interventions may work

There are two objectives of the interventions: first to get accommodation, and then to avoid eviction. Housing programs provide accommodation to individuals. Case management (low or high intensity) is intended to compensate for the clients’ lack of resources and to help them either obtain accommodation, and/or after they have become housed, avoid eviction. It is a collaborative process, including assessment, planning, facilitation and advocacy for options and services.

Why it is important to do this review

Efforts to combat homelessness have been made on national levels as well as at local government level, including specific treatments for particular types of clients. In addition, there have been many evaluations of housing and treatment programs for homeless individuals and/or persons at risk of homelessness. Several reviews and meta‐analyses have also been published (12, 18, 20, 28‐31). Yet, a large share of the reviews are out of date, or do not focus on homelessness and residential stability as primary outcomes, or are not systematic reviews of effectiveness.

Tabol and colleagues (2010) (12) aimed to determine how clearly the supported/supportive housing model is described and the extent to which it is implemented correctly (treatment fidelity). Another recent systematic review by de Vet and colleagues focussed on case management for homeless persons. They identified 21 randomized controlled trials or quasi‐experimental studies, but did not conduct a meta‐analysis, or GRADE the certainty of the evidence. A review by Chilvers and colleagues published in 2006 looked specifically at supported housing for adults with serious mental illness, but did not identify any relevant studies(32).

This review differs from previous attempts at reviewing the evidence in that we have only included randomized controlled trials that examine a broad range of interventions with follow‐up of at least one year. Furthermore, we have pooled the results where possible which has allowed us to look at the evidence across studies and not conclude based on small sample sizes from individual studies. Finally, we have applied GRADE to the outcomes, thus providing a more concrete indication of our certainty in the evidence.

Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the effectiveness of various interventions combining housing and case management as a means to reduce homelessness and increase residential stability for individuals who are homeless, or at risk of becoming homeless. Interventions include:

Abstinence‐contingent housing, non‐abstinence contingent housing, housing vouchers and residential treatment

High intensity case management (intensive case management and assertive community treatment), and low (ordinary or brokered) case management

Housing programs combined with case management programs.

Methods

This systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to reduce homelessness and increase residential stability for people who are homeless was conducted in accordance with the guidelines in the NOKC Handbook for Summarizing Evidence (33) and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (22).

This review was carried out in two phases. The first phase began with a literature search in 2010. The project was taken over in 2014 by the current review team and two updates to the original search were conducted in addition to a search for grey literature. We reassessed studies included by the original review team for inclusion, and excluded those with a quasi‐experimental design (see further details below). Due to problems with archiving, there is no documentation of reasons for exclusion for some of the studies excluded in the first phase of the project.

A protocol was approved and published by the review team in the Campbell Library in 2010. The protocol was used as the basis for the development of a protocol by the current review team which was approved and published on the NOKC website in 2014(34). The updated searches (2014 and 2016) were based on the search specified in the Campbell approved protocol, and the inclusion criteria aresimilar, aside from study design. There are four main differences between the protocol published in Campbell Library and the protocol for the current review: Firstly, in this review protocol we only included RCTs. This decision was based on the number of RCTs identified, which seemed sufficient even after the original search. Secondly, we did not include data or analyses related to cost effectiveness as these outcomes were not prioritized by our commissioners. Thirdly, we did not exclude studies if they did not sufficiently report the results. The results from these studies were reported narratively. Finally, we applied the GRADE approach to all primary outcomes.

Literature search

We systematically searched for literature in the following databases. Unless otherwise noted, the databases were searched in 2016, 2014, and 2010. Any databases that were not searched in 2016 and 2014 is due to lack of access. There were no limitations on the search with respect to date of publication (i.e. the databases were searched for their entirety since indexing began).

PsycINFO

ASSIA (2014, 2010)

Campbell Library (2016)

Cochrane Library (including CENTRAL)

PsychInfo (2016, 2014)

PubMed

Social Services Abstracts

Sociological Abstracts

ERIC (2016, 2014)

CINAHL

ISI Web of Science (2016, 2014)

In addition, we conducted a search for grey literature through Google and Google Scholar and reference lists of identified and included studies using terms related to homelessness and housing. This search for grey literature was conducted in English, Norwegian, Swedish and Danish.

A research librarian planned and executed all the searches. The complete search strategy is published as an appendix to this report (Appendix 2). The search was last updated in January 2016.

Inclusion criteria

|

Study design: |

Randomized controlled trials |

|

Population: |

People who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless. A homeless person is defined as a person living in the streets without a shelter that could be classified as “living quarters”with no place of usual residence and who moves frequently between various types of accommodation (including dwellings, shelters, institutions for the homeless or other living quarters) which may include living in private dwellings but reporting “no usual/permanent address” on their census form. A person at risk of becoming homeless is someone who will be released from a prison, an institution (e.g. for psychiatric or rehabilitative care), or another accommodation within two months, and does not have any housing arranged for them in the near future (35). A person at risk can also be a person who lives temporarily with relatives or friends, or a person with short‐term subletting contracts who has applied to social services or another organization for assistance in solving their housing situation. There were no population restrictions regarding mental illness, addiction problems, age, gender, ethnicity, race, national contexts, etc. However, distinct subgroups were separated in our analyses when there was sufficient information in included studies. |

|

Intervention: |

Housing programs or case management or a combination of the two types of interventions. Qualified housing programs and forms of case management must meet the criteria defined by the Society for Prevention Research (36). To meet this standard, a detailed description of the program or policy must be available (p.4): “An adequate description of a program or policy includes a clear statement of the population for which it is intended; the theoretical basis or a logic model describing the expected causal mechanisms by which the intervention should work; and a detailed description of its content and organization, its duration, the amount of training required, intervention procedures, etc. The level of detail needs to be sufficient so that others would be able to replicate the programme or policy. With regard to policy interventions, the description must include information on relevant variations in policy definition and related mechanisms for implementation and enforcement.” |

|

Comparison: |

Any other intervention or treatment/services as usual. |

|

Outcome: |

Primary outcomes: homelessness and residential stability. The minimum follow up is 12 months after intake. Continuous data should describe the housing situation during specific periods, for instance, the past 30, 60, or 90 nights. This could be the mean number of nights, or the mean proportion of nights in a particular housing situation. Dichotomous data should involve the number of persons or the proportion of persons in different housing situations. Housing situations should be at least one of the following: homeless, unstable housing, or stable housing. Our goal is to use standardized definitions. Whether this is possible or not depends on the information given in included primary studies. For an outcome to be included in the meta‐analysis, necessary statistical information for calculating effect sizes or relative risks must be available. If such information is not available in identified documents or provided by authors when contacted, these outcomes and studies will be included in a narrative summary only. Secondary outcomes: (only included if primary outcomes are available) health‐related outcomes including presence/severity of mental illness or substance abuse, quality of life, marginalization, employment, criminal behaviour, school attendance. |

|

Language: |

No restrictions regarding language. |

Exclusion criteria

|

Study design: |

Other study designs, including quasi‐experimental studies with propensity score matching. |

|

Outcome: |

Outcomes only related to admission to hospital/psychiatric treatment, or cost‐related outcomes. However, studies were included if they also included primary outcomes. |

We originally included quasi‐experimental designs for consideration when they met the other study criteria and used propensity score matching at baseline. However, given the number of randomized controlled trials identified in the updated literature search, we decided to limit inclusion to randomized controlled trials only. We thus excluded eleven studies from the final review. Given the inherent methodological limitations of quasi‐experimental designs in answering effectiveness questions, we do not believe that this decision influenced the final results of this review.

Article selection

Two reviewers independently read and assessed references (titles and abstracts) for inclusion according to pre‐defined inclusion criteria (see above). When at least one review author considered the reference potentially relevant, the reference was ordered to be read in full‐text. Two reviewers independently read and assessed each article in full‐text for inclusion according to a pre‐defined inclusion form. Where differences in opinion emerged, the reviewers discussed until consensus was achieved. A third reviewer was brought in in instances where agreement was not possible, to assist in the decision.

Critical appraisal

The included studies were assessed for methodological limitations using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) tool (37). Studies were assessed as having low, unclear or high risk of bias related to: (1) randomization sequencing, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding of personnel and participants, (4) blinding of assessors for subjective outcomes and (5) objective outcomes, (6) incomplete outcome data, (7) selective reporting and (8) any other potential risks of bias. One reviewer assessed each study and a second reviewer checked each assessment and made comments where there were disagreements. Results of the Risk of Bias assessments were discussed until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

One reviewer systematically extracted data from the included studies using a pre‐designed data recording form. A second reviewer then checked the data extraction for all included studies. Any differences or comments were discussed until consensus was achieved.

The following core data were extracted from all included studies:

Title, authors, and other publication details

Study design and aim

Setting (place and time of recruitment/data collection)

Sample population characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, mental health/substance use status, homelessness status, criminal activity)

Intervention characteristics (degree and type of housing support and degree/type of service support and/or therapy offered)

Methods of outcome measurement (clinical, self‐report, physical specimens for substance use outcomes)

Primary outcomes related to number of days spent in stable housing or homeless

Secondary outcomes related to housing (satisfaction with housing, type of housing, etc.), addiction status, mental or physical health, criminal activity, and/or quality of life.

Many of the studies were reported in more than one publication. One publication was identified as the main publication (usually the one with results related to the primary outcomes), and we only extracted data from publications in addition to the identified main publication when they added more information regarding the methods or results on relevant outcomes. We excluded studies if they reanalysed already included data using different techniques.

Given the complexity of the interventions being investigated, we attempted to categorize the included interventions along four dimensions: (1) was housing provided to the participants as part of the intervention; (2) to what degree was the tenants’ residence in the provided housing dependent on, for example, sobriety, treatment attendance, etc.; (3) if housing was provided, was it segregated from the larger community, or scattered around the city; and (4) if case management services were provided as part of the intervention, to what degree of intensity. We created categories of interventions based on the above dimensions:

-

1.

Case management only

-

2.

Abstinence‐contingent housing

-

3.

Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing

-

4.

Housing vouchers

-

5.

Residential treatment with case management

Some of the interventions had multiple components (e.g. abstinence‐contingent housing with case management). These interventions were categorized according to the main component (the component that the primary authors emphasized). They were also placedin separate analyses. We then organized the studies according to which comparison intervention was used (any of the above interventions, or usual services).

For each comparison, we evaluated the characteristics of the population. In those cases where they were considered sufficiently similar (specifically with respect to individuals versus families, mental illness, substance abuse problems, literally homeless versus at risk of homelessness), and had comparable outcomes, the results from the studies were pooled in a meta‐analysis when possible. In those cases where the populations of studies with the same comparisons were considered too different to analyse together we have not pooled the results.

We extracted dichotomous and continuous data for all outcomes where available. We also extracted raw data and, when such data were available, adjusted outcome data (adjusted comparison (effect) estimates and their standard errors or confidence intervals). When information related to outcome measurement (e.g. sample sizes, exact numbers where graphs were only published in the article) were missing in the publication, we contacted the corresponding author(s) via e‐mail and requested the data.

Data synthesis

Results for the primary outcomes (number of days spent in stable housing or homeless) are presented for each comparison along with a GRADE assessment. Results for secondary outcomes (for longest follow‐up time) for each comparison were not synthesized, but are presented in Appendix 4. For comparisons where more than two studies are included, we present the primary outcomes with the longest follow‐up time. Results for secondary outcomes are described in Appendix 4.

We summarized and presented data narratively in the text and table for each comparison. We also conducted a meta‐analysis with random effects model and presented the effect estimate, relative risk and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) using risk ratio for dichotomous outcomes. For continuous outcomes we analysed the data using (standardized) mean difference ((S)MD) with the corresponding 95% CI. We used SMD when length of time was measured different between pooled studies (e.g. in days versus months, etc.). We conducted meta‐analyses using RevMan 5,using a random‐effects model and inverse‐variance approach(38). This method allowed us to weight each study according to the degree of variation in the confidence in the effect estimate.

In cases where the means, number of participants and test statistics for t‐test were reported, but not the standard deviations, and there was the opportunity to include results in a meta‐analysis, we calculated standard deviations, assuming same standard deviation for each of the two groups (intervention and control).

Heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity using I2. Where I2was less than 25% we considered the results to have low heterogeneity. Where I2 was greater than 50% we considered the results to have high heterogeneity. Where this heterogeneity could be explained, we proceeded to pool results. However, if heterogeneity could not be explained, we did not pool the results and presented the results separately for each study.

Subgroup analysis

We did not plan or conduct moderator or subgroup analyses.

Dependent effect sizes

We did not include a comparison group more than once in an analysis. Where we were interested in an intervention and it was compared to two or more comparison interventions that were both considered to be within the realm of “usual services”, we combined the two comparison arms into one comparison group and compared the means of the combined control groups to the intervention for a given outcome (39).

In one study we have combined two intervention arms that both employed slightly differing versions of an intervention (assertive community treatment) into one intervention group and compared that to the usual services comparison condition (40).

Primary outcomes

Outcomes related to housing and homelessness were reported using multiple measurements/scales/methods in some studies. These included number of days spent in stable housing or homeless, length of time to move from shelter to permanent housing (measured in days), number or percentage of participants who reported being homeless during a given period, or at a certain measurement point, and the change in number/proportion of days spent in various living conditions between baseline and follow‐up points.

Secondary outcomes

We did not synthesize or report results for secondary outcomes. They are described in Appendix 4 as they are reported in the original primary publications.

GRADING of the evidence

We assessed the certainty of the synthesized evidence for each primary outcome using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation). GRADE is a method for assessing the certainty of the evidence in systematic reviews, or the strength of recommendations in guidelines. Evidence from randomized controlled trials start as high certainty evidence but may be downgraded depending on five criteria in GRADE that are used to determine the certainty of the evidence: i) methodological study quality as assessed by review authors, ii) degree of inconsistency, iii) indirectness, iv) imprecision, and v) publication bias. Upgrading of results from observational studies is possible according to GRADE if there is a large effect estimate, or a dose‐response gradient, or if all possible confounders would only diminish the observed effect and that therefore the actual effect most likely is larger than what is suggested by the data. GRADE has four levels of certainty:

High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate.

Assessments are done for each outcome and are based on evidence coming from the individual primary studies contributing to the outcome. For more information on GRADE visit www.gradeworkinggroup.org, or see Balshem and colleagues 2011 (41).

For a detailed description of the Norwegian Knowledge Centre's procedures, see the Norwegian Knowledge Centre's Handbook(33).

Results

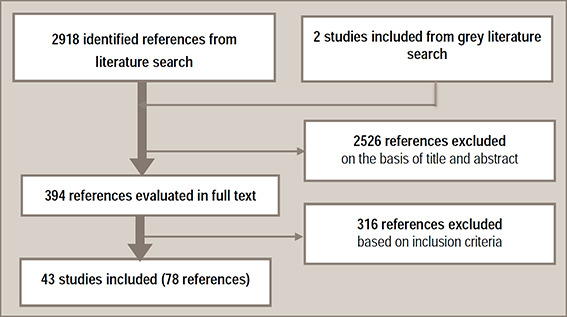

The search was conducted in three stages. The original systematic search of databases in 2010 resulted in 1,764 unique references (Figure 1). We identified a further831 unique references from the update search in2014, and 323 more in the January 2016 update search. Altogether we identified 2,918potentially relevant references through database searches. In addition, a grey literature search identifiedan additional 2 relevant studies (and 11 references). We excluded 2,526references based on title and abstract. We read 394 references in full and excluded 316 based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. In total, we critically appraised 43 studies that were described in 78 publications. A list of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion is included in Appendix 5. Problems related to archiving from the first search in 2010 resulted in missing the references and the reasons for exclusion for 50 excluded studies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature selection process

Description of the included studies

We identified 43 randomized controlled studies (RCTs) reported in 78 publications (24, 26, 27, 39, 40, 42‐81)that met our inclusion criteria, and two studies in progress (31, 82). See Appendix 9 for a description of the studies in progress.

Thirteen of the included studies were published in or after 2010, thirteen were published between 2000 and 2009, and seventeen studies were published before 2000.

The majority of the studies were conducted in the United States (n=37), and other included studies came from other high‐income countries, including United Kingdom (n=3), Australia (n=1), Canada (n=1), and Denmark (n=1). Eleven of the studies were conducted at multiple sites (cities/institutions).

The duration of the intervention was not reported in all of the included studies. It appears that in most of these cases the intervention was available/offered until the longest follow‐up. There were also some discrepancies between the number of participants randomized and the number of participants included in analyses in some cases. We have highlighted where we think this is a concern.

From these 43 RCTs we have summarized findings from 28 comparisons in five categories of interventions (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of comparisons of case management interventions

|

Category |

Intervention |

Comparisons |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Case management |

1. A. High intensity case management |

1. A.1. Usual services |

|

1.A.2. Low intensity case management | ||

|

1.A.3. Other intervention (no case management or housing program) | ||

|

1.A. High intensity case management (with consumer case management) |

1.A.4. High intensity case management (without consumer case management) |

|

|

1.B. Low intensity case management |

1.B.1. Usual services |

|

|

1.B.2. Low intensity case management | ||

|

1.B.3. Other intervention (no case management or housing program) | ||

|

1.C. Critical time intervention |

1.C.1. Usual services |

|

|

Abstinence‐contingent housing programs |

2.A. Abstinence‐contingent housing with case management |

2.A.1. Usual services |

|

2.A.2. Case management | ||

|

2.B. Abstinence‐contingent housing with day treatment |

2.B.1. Usual services |

|

|

2.B.2. Day treatment | ||

|

2.B.3. Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing with day treatment | ||

|

2.B.4. Abstinence‐contingent housing with community reinforcement approach | ||

|

3. Non‐abstinence contingent housing programs |

3.A. Housing First |

3.A.1. Usual services |

|

3.A.2. Abstinence‐contingent housing | ||

|

3.B. Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing with high intensity case management |

3.B.1. Usual services |

|

|

3.B. Non‐abstinence‐contingent group living arrangements with high intensity case management |

3.B.2. Non‐abstinence‐contingent independent apartments with high intensity case management |

|

|

3.B. Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing with high intensity case management |

3.B.3. Abstinence‐contingent housing with high intensity case management |

|

| 3.B. Non‐abstinence‐contingent housing with day treatment |

3.B.4. Day treatment |

|

|

4. Housing vouchers with case management |

4. Housing vouchers with case management |

4.1. Usual services |

|

4.2. Case management | ||

|

5. Residential treatment |

5. Residential treatment |

5.1. Usual services |

Risk of bias in the included studies

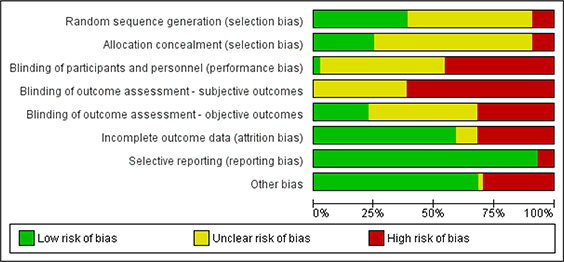

The majority of the RCTs were assessed as having high risk of bias. In many instances this was due to inadequate reporting of methods in general (unclear risk of bias). In particular, most studies were at unclear or high risk of selection bias because they either did not report randomization or allocation concealment procedures or reported inadequate methods of randomization or allocation concealment. The vast majority of studies were assessed as having unclear or high risk of performance bias: Blinding of participants and personnel was either not described in many studies (unclear risk), or not possible and reported as such (high risk). In the majority of studies outcome assessors were not blinded (high risk), or blinding was not mentioned (unclear risk). The risk of bias was separated into blinding of outcome assessment for subjective and objective outcomes due to the poor reporting, or lack, of blinding. The intention behind this was to indier4’;cate that the blinding might have an impact on subjective outcomes, but not objective outcomes such as death or number of days housed when the data came from administrative records. Some studies also were assessed as being at high risk for attrition bias because they used inappropriate methods for dealing with missing data, or reporting bias because the results were not reported for all outcomes. It is not clear how much attrition has occurred in many of the primary studies, and in some cases the level of attrition differs between results within the same study but is not discussed by the primary authors. See Appendix 6 for a more detailed explanation of the risk of bias assessment for each study.

Interventions and comparisons

We included and extracted data from 43RCTs(this information was presented in 78 publications). Some studies included multiple comparisons (multiple interventions), and some publications reported results from multiple studies (for example information related to two studies in one publication). Details on all of the included comparisons are described below. Details regarding data related to secondary outcomes is not reported in the main text of this report but can be found in Appendix 4.

The case management component in the included studies varied in terms of approach, intensity and case‐load for case managers. We have therefore categorized case management components as either low intensity (case management with no further details, brokered case management), high intensity (Assertive Community Treatment or Intensive Case Management), or Critical Time Intervention (intensive case management for a shorter defined period of time). In addition, some interventions included a housing component and a treatment component that could not be described as case management (e.g. day treatment or Community Reinforcement Approach). Interventions including these treatment components have been analysed separately from interventions that include low or high intensity case management components. Most of the interventions evaluated in the included comparisons were complex in that they were made up of multiple components, and there was a large degree of flexibility in terms of how the interventions were implemented (including varying levels of treatment fidelity). Furthermore, many of the studies reported that the interventions and control conditions changed and evolved during the course of the studies in terms of organization, and availability of resources and services. More details on the interventions evaluated in each study is reported under the relevant comparison.

The comparison groups varied considerably, and in many cases it is difficult to ascertain what kind of interventions participants in these groups received/were offered due to poor reporting. The comparison groups were described as usual services (care as usual), other types of housing programs or case management interventions, or other types of interventions. All of the comparison groups, however, received some type of active intervention. That is, even participants in the usual services groups had access to drop in centres, and to some degree case management and/or shelter.

Population in the included studies

A total of approximately 10,570 participants were included in the identified studies. This is an approximate number due to poor reporting in many of the studies. The majority of the studies included adults who had a mental illness or substance dependence and were homeless or at‐risk of becoming homeless due to the previous mentioned illnesses. More detail on the populations in the included studies is available under each comparison.

Description of outcomes reported in the included studies

All of the included studies reported at least one outcome related to homelessness or housing stability. This was reported in various ways including the number of days participants reported being housed/homeless, proportion of participants homeless or housed at follow‐up, time to exit from/return to shelter, and frequency of address change. Many of the included studies also included outcomes related to employment, mental or physical health, quality of life, social support and criminal activity. Details regarding outcomes are described under each comparison.

Secondary outcomes for each comparison are presented in Appendix 8.

Category 1: Case management

Description of included studies

We identified 26 studies with four comparisons that evaluated the effect of case management on housing stability and/or homelessness (26, 39, 40, 44‐48, 50, 52‐54, 56, 59, 60, 64, 69‐72, 74, 76, 77, 79, 80, 83). The majority of the studies were conducted in the USA (N=22), with the remaining studies from either Australia (N=1), Denmark (N=1) or the United Kingdom (N=3). Data for the included studies were collected between the 1980s (earliest published study from 1990, but it is unclear when data was collected) and 2009, and thus represent varying populations and settings in terms of political and social climate in the various countries and states where the studies are conducted. The exact number of participants is not always clearly reported. We have reported the total number randomized and included in analyses where possible.

Within the category of case management, we identified four subcategories of interventions which were compared to usual services or other interventions. See Table 2 for an overview.

Table 2.

Overview of case management comparisons

|

Intervention |

Comparisons |

|---|---|

|

1.A. High intensity case management |

1.A.1. Usual services |

|

1.A.2. High intensity case management (without consumer case management) | |

|

1.A.3. Low intensity case management | |

|

1.A. High intensity case management(with consumer case management) |

1.A.4. Other intervention (no case management or housing program) |

|

1.B. Low intensity case management |

1.B.1. Usual services |

|

1.B.2. Low intensity case management | |

|

1.B.3. Other intervention (no case management or housing program) | |

|

1.C. Critical time intervention |

1.C.1. Usual services |

Table 3 presents an overview of the populations, interventions, comparisons and outcomes in the included studies. The total number of participants indicates the number of participants randomized. The number of participants for each group does not always add up to the total number of participants because most studies reported the number included in analyses, but not always the number randomized. Participants in the included studies were adults (>18 years old) unless otherwise specified. We report the longest outcome assessment for each study (shorter follow‐up assessments were also done in some studies).

Table 3.

Description of studies that evaluated effects of case management interventions (N=26)

|

Study (ref); country |

Population (N, description) |

Intervention Follow‐up (FU) in months (mos), N |

Comparison N |

Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIGH INTENSITY CASE MANAGEMENT (N=18) | ||||

|

Bell 2015 (44), USA |

N=1380, disabled Medicaid beneficiaries with mental health and/or substance abuse problems and comorbid physical conditions |

Intensive care management FU: 24 mos N=690 |

Usual services (wait‐list) N=690 |

Mean number of homeless months per 1000 months Proportion of participants with any homeless months |

|

Bond 1990 (45)(45), USA |

N=88, serious mental illness, multiple hospitalizations |

Assertive community treatment FU: 12 mos N=45 |

Drop‐in centre N=43 |

Housing stability Living arrangements |

|

Grace 2014 (46), multisite, Australia |

N=396 18‐35, (previously) homeless, receiving financial aid |

Intensive case management FU: 18‐30 mos N=222 |

Usual services N=174 |

Number of moves Housing status Number of homelessness events |

|

Clarke 2000 (48), USA |

N=178, chronically mentally ill |

Assertive community treatment FU: 24 mos N=114 |

Usual care N=49 |

Time to first instance of homelessness |

|

Cox 1998 (50), USA |

N=298 homeless, substance dependence |

Intensive case management FU: 18 mos N=150 |

Usual care N=148 |

Nights in own residence, nights homeless |

|

Drake 1998 (52), multisite, USA |

N=224, 18‐60, mental illness, substance abuse disorder, no additional medical conditions |

Integrated Assertive community treatment FU: 36 mos N=105 |

Standard case management N=98 |

Days in stable housing |

|

Essock 2006 (53), multisite, USA |

N=198 severe mental illness |

Integrated Assertive community treatment FU: 36 mos N=99 |

Standard case management N=99 |

Days in stable housing |

|

Garety 2006 (54), UK |

N=144 mental illness |

Assertive Community treatment FU: N=71 |

Usual services N=73 |

Not stably housed |

|

Killaspy 2006 (59), multisite, UK |

N=251 severe mental illness |

Assertive community treatment FU: 18 mos N=127 |

Usual services N=124 |

Not homeless |

|

Lehman 1997 (60), USA |

N=126 severe mental illness |

Assertive community treatment with housing opportunities FU: 12 mos N=77 |

Usual services N=75 |

Days in community housing Days homeless |

|

Morse 1992 (39), USA |

N=178 (103 analyzed), homeless adults with mental illness |

Assertive community treatment FU: 12 mos N=52 |

Drop in centres N=62 or outpatient services N=64 |

Days not homeless Days homeless |

|

Morse 1997 (40), USA |

N=165 (85 analyzed), homeless, mental illness |

Assertive community treatment with/out community workers FU: 18 mos N=35/28 |

Brokered case management N=22 |

Days in different housing settings Days not stably housed |

|

Morse 2006 (69), USA |

N=196 (149 analyzed), homeless, mental illness, substance dependence |

Assertive community treatment with/out integrated treatment FU: 24 mos N=46/54 |

Usual services N=49 |

Days in stable housing |

|

Nordentoft 2010 (70), multisite, Denmark |

N=275 mental illness |

Assertive community treatment FU: 5 years N=275 |

Usual services N=272 |

Days homeless |

|

Rosenheck 2003 (71), multisite, USA |

N=278 homeless veterans, mental illness and/or substance abuse |

Intensive case management only FU: 36 mos N=90 |

Usual services N=188 |

Stably housed Homeless |

|

Solomon 1995 (76), USA |

N=96 (90 analyzed) major mental illness |

Consumer case management FU: 24 mos N=48 |

Non‐consumer case management N=48 |

Homelessness |

|

Toro 1997 (80), USA |

N=202 homeless families |

Intensive case management, employment training and housing FU: 18 mos N=101 |

Usual services N=101 |

Days homeless |

|

Nyamathi 2015 (83), USA |

N=600 men recently released from prison/jail |

Intensive case management with peer coaching FU: 12 mos N=166 |

Usual services N=186 Peer coaching N=177 |

Homelessness |

| LOW INTENSITY CASE MANAGEMENT (N=5) | ||||

|

Chapleau 2012 (47), USA |

N=57 at risk or homeless, severe mental illness |

Case management with Occupational therapist FU: 12 mos N=29 |

Case management N=28 |

Housing status

|

|

Marshall 1995 (64), USA |

N=80 mental illness |

Case management FU: 14 mos N=40 |

Usual services N=40 |

Days in better/worse accomodation |

|

Slesnick 2015 (74), USA |

N=270 homeless youth, substance abuse problems |

Case management Duration: 12 mos N=91 |

Community reinforcement approach N=93 Motivation Enhancement therapy N=86 |

Homelessness |

|

Sorensen 2003 (77), USA |

N=190 substance abusers, HIV/AIDS |

Case management Duration: 12 mos FU: 18 mos N=92 |

Brief contact N=98 |

Homelessness |

|

Sosin 1995 (26), USA |

N=191 analyzed, homeless, substance dependence |

Abstinence‐contingent housing with case management Duration: average 6 mos FU: 12 mos N=70 |

Usual care N=121 |

Number of days housed of previous 60 days |

| CRITICAL TIME INTERVENTION (N=3) | ||||

|

Herman 2011 (56), USA |

N=150 recently discharged, psychotic disorder |

Critical Time Intervention with post‐discharge housing FU: 18 mos N=77 |

Usual services with post‐discharge housing N=73 |

Days homeless Homeless at baseline |

|

Samuels 2016 (72), USA |

N=223 (210 analyzed) homeless mothers, mental illness |

Critical time intervention with scattered site housing Duration: 9 mos FU: 15 mos N=97 |

Usual services N=113 |

Number of days to move out of shelter Proportion of days homeless |

|

Susser 1997 (79), USA |

N=96, homeless adult men, severe mental illness |

Critical Time Intervention with supportive housing Duration: 18 mos N=48 |

Usual services N=48 |

Days homeless |

Description of the intervention

The case management intervention in the included studies varied considerably in terms of intensity, organization and length. The interventions are described in more detail under the relevant comparison and in Appendix 7.

Category 1.A: High intensity case management

We identified 18 studies that evaluated the effect of high intensity case management on housing stability and/or homelessness (39, 40, 44‐46, 48, 50, 52‐54, 59, 60, 69‐71, 76, 80, 83). High intensity case management included interventions which were described as using either Assertive Community Treatment (ACT; N=12) or intensive case management (ICM; N=6). The included interventions varied in terms of ratio of clients per case manager, frequency of contact, length of treatment and follow‐up, location of appointments, degree of service provision versus referral, and team versus individual approach to case management.

The interventions in the majority of the included studies (N=13) are compared to usual services (44‐46, 48, 50, 54, 59, 60, 69‐71, 80, 83). One study compared the intervention to another type of high intensity case management (76) and two studies compared it to low intensity case management (53, 69). In two of the included studies, multiple intervention arms or comparison arms were relevant for this category of interventions (39, 40). In one study we have combined two intervention arms that both employed slightly differing versions of assertive community treatment into one intervention group compared to usual services (40). In the other study (39), we combined two comparison arms that both offered usual services to participants into one comparison group compared to the intervention.

Services provided as part of “usual services” varied greatly between and within the studies. We have chosen to include all studies that compared high intensity case management to “usual services” in one comparison. The term “usual services” covers a wide variety of services, but generally refers to the variety of services available to any person meeting the eligibility criteria of the study and not an alternative intervention which participants who are not randomized to the intervention group receive. Usual services in the included studies included drop‐in centres, provision of a list of services and information (69), case management style services (59)and limited peer coaching(83). Control conditions were too poorly described in most studies to accurately document what participants had access to.

1.A.1. High intensity case management compared to usual services

We identified 18 studies (39, 40, 44‐46, 48, 50, 52‐54, 59, 60, 69‐71, 76, 80, 83) which evaluated the effect of high intensity case management compared to usual services on housing stability and homelessness in the USA (N=15), United Kingdom (N=2) and Denmark (N=1). The included studies were conducted over a long span of time; however, the majority of studies were conducted or began before the end of 2000 (N=12).

Fifteen of the included studies focused on adults with mental illness and/or substance abuse issues (39, 40, 44, 45, 48, 50, 52‐54, 59, 60, 69‐71, 76). One study focused on disadvantaged youth (46), one study included adults with families (80), and one study targeted recently released criminal offenders (83). While the studies differed slightly in the populations targeted, all of the studies included participants with mental illness and/or substance abuse even when that was not the main identifying characteristic of the target population. Information regarding mental illness and substance abuse was not reported for the study on disadvantaged youth; however, there was little reason to assume that this group would react differently to the intervention. More importantly, given the outcomes analysed here, housing stability and homelessness, one can assume that this is a universally sought after outcome, and the characteristics of the population might not be considered to be important. Below is a description of the results.

Primary outcome: Housing stability

Six of the included studies examined housing stability for adults with mental illness and/or substance dependence issues (45, 46, 50, 54, 59, 60, 69).

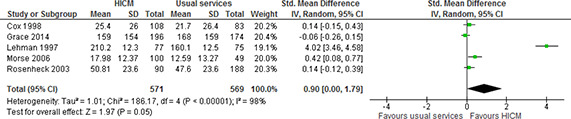

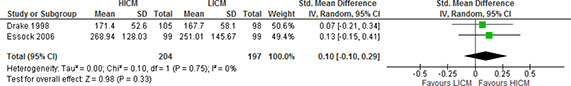

We carried out a meta‐analysis for number of days in stable housing, pooling available data from four included studies (46, 50, 60, 69, 71) to examine the effect of high intensity case management compared to usual services on number of days in stable housing. As evident from the forest plot (Figure 2), the pooled analysis indicates that the high intensity case management leads to an increase in the number of days spent in stable housing compared to usual services (SMD=0.90, 95%CI=0.00 to 1.79). Although considerable heterogeneity is indicated by I2 and Chi2(I2=98%, chi2=186.17), this is expected due to the complexity of the included interventions, the geographical range of included studies (multiple cities across USA, and Australia) and the wide range of when the interventions were implemented.

Figure 2.

Number of days in stable housing, 12‐24 months follow‐up, high intensity case management vs usual services

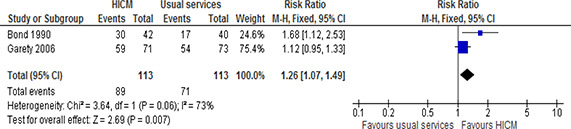

We carried out a meta‐analysis to estimate the number of participants in stable housing at 12‐18 months after the start of the intervention, pooling available data from two included studies (45, 54). As evident from the forest plot (Figure 3), the pooled analysis indicates that high intensity case management leads to a greater number of individuals living in stable housing compared to usual services (RR=1.26, 95%CI= 1.07 to1.49). While the heterogeneity was assessed as being high (I2=73%, chi2=3.64), this can be accounted for by differences in when the interventions were implemented (approximately 15 years between publications) and assessed and geographical differences (UK and USA). Together these differences may have implications for political or social contexts which may, in turn, have impacted, for example, the type of usual services being provided.

Figure 3.

Number of participants in stable housing, 12‐18 months follow‐up, high intensity case management vs usual services

It is uncertain whether high intensity case management improves either the length of time individuals spend in their longest recorded residence, the number of clients who do not move (45), or the number of moves during the last half of a one or two year period (45).

One study reported that there was no difference between the intervention and control groups in the number of moves reported during the previous 12 months as measured at 24 months MD=0.30 (‐0.04, 0.64)(46).

Primary outcome: Homelessness

Thirteen of the included studies examined homelessness (39, 44‐46, 48, 50, 54, 59, 60, 70, 71, 80, 83). Seven studies reported outcomes related to length of time homeless, either in terms of number of months (44) or number of days (39, 46, 50, 60, 71, 80).

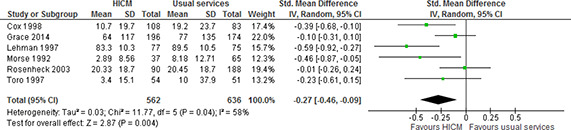

We carried out a meta‐analysis for the number of days spent homeless, pooling available (adjusted) data from six included studies (39, 46, 50, 60, 71, 80). One of the studies adjusted the results for demographic characteristics, specifically ethnicity (60). This study (60)also reported both number of days homeless in shelter and number of days homeless on streets. It was not possible to combine the data from these two outcomes (means and the standard error of the mean (SEM) were reported, but not the number of participants who reported experiencing these living arrangements), so we have chosen to include the number of days homeless in shelter in this meta‐analysis. The pooled estimate indicates that high intensity case management leads to fewer days spent homeless compared to usual services. Although there is considerable heterogeneity (I2=58%, chi2=11.77), this may be explained by a wide range of geographical settings (USA and Australia), and large differences in when the interventions were implemented and assessed (from 1990s to 2006). Together these differences may have implications for political or social contexts which may, in turn, have impacted, for example, the type of usual services being provided.

Figure 4.

Number of days homeless, 12‐24 months, high intensity case management vs usual services

In one study (44), high intensity case management seemed to lead to fewer months homeless (mean number of months per 100 months homeless). However, the 95% confidence interval indicates that high intensity case management might make little or no difference the amount of time spent homeless (results as reported in original publication: n=‐1.5 [95%CI ‐4.3 to 1.3], p=0.29).

One study reported that participants in the high intensity case management group reported spending almost half as many days living on the street than participants in the usual services group (MD=0‐14.10 (‐15.77, ‐12.43))(60)

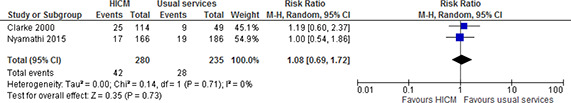

Three studies reported whether participants experienced homelessness during the study period (44, 48, 83). We conducted a meta‐analysis for the number of participants who experienced at least one episode of homelessness within one to two years, pooling data from two studies (48, 83). The third study was not included in the analysis due to incomplete reporting of results (baseline and follow‐up percentage of participants was not reported, only the pre‐post difference in percentage of participants who experienced homelessness during a two year period was reported along with the difference in difference (44).

The pooled analysis, shown in Figure 5, indicates that high intensity case management may lead to little or no difference in whether individuals experience homelessness during a one to two year period compared to usual services. Results, as reported in the original publication, from the third study support this (Bell 2015 (44): OR=0.83, 95%CI=0.60 to 1.17).

Figure 5.

Number of participants who experienced at least one episode of homelessness, 12‐24 months, high intensity case management vs usual services

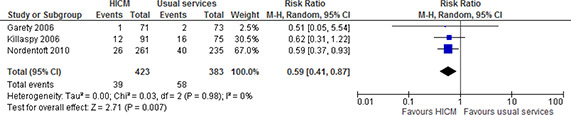

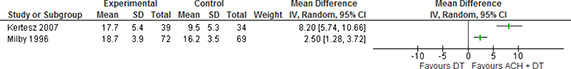

Three studies examined the number of participants who reported being homeless at the last follow‐up point (12 to 18 months after baseline) (54, 59, 70). We conducted a meta‐analysis for the number of participants who were homeless 12 to 18 months after the beginning of the study, pooling available data from three studies (54, 59, 70). One study reported the percentage of participants per group, but not the total number per group (amount of data on participants varied according to outcome), so we calculated the total number of participants per group using the information provided (70). As evident from the forest plot (Figure 6), the pooled analysis indicates that high intensity case management probably leads to fewer individuals who report being homeless at the 12 to 18 month follow‐up interview compared to usual services (RR=0.59, 95%CI=0.41 to 0.87).

Figure 6.

Number of participants who were homeless at last follow‐up point, 18 months, high intensity case management vs usual services

The results and quality assessments for high intensity case management compared to usual services on housing stability and homelessness for adults with mental illness and/or substance abuse problems are summarized in Table 4. The complete GRADE evidence profile is shown in Appendix 8, Table 8.1.1.

Table 4.

Summary of findings table for the effects of high intensity case management compared to usual services (Bell 2012, Bond 199, Cox 1998, Grace 2014, Garety 2006, Killaspy 2006, Nordentoft 2010, Nyamathi 2015, Toro 1997)

|

Patient or population: adults who are homeless or at‐risk of becoming homeless Setting: USA, Intervention: high intensity case management Comparison: usual services | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Outcomes |

Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) |

№ of participants (studies) |

Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

| Risk with usual services |

Risk with high intensity case management |

||||

|

Number of participants homeless at follow‐up assessed with: self‐report follow up: range 12 months to 18 months |

151 per 1 000 |

89 per 1 000 (62 to 132) |

RR 0.59 (0.41 to 0.87) |

806 (3 RCTs)12 |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE 5 |

|

Number of participants living in stable community housing at follow‐up assessed with: self‐report follow up: range 12 months to 18 months |

628 per 1 000 |

792 per 1 000 (672 to 936) |

RR 1.26 (1.07 to 1.49) |

226 (2 RCTs) |

⨁⨁◯◯ |

|

Number of participants who experienced some homelessness assessed with: not reported follow up: 24 months |

119 per 1,000 |

129 per 1,000 (82 to 205) |

RR 1.08 (0.69 to 1.72) |

1635 (3 RCTs)7 |

⨁⨁◯◯ |

|

Number of days homeless assessed with: self‐report follow up: range 12 months to 24 months |

‐ |

SMD 0.27 SD fewer (0.46 fewer to 0.09 fewer) |

‐ |

1198 (6 RCTs) |

⨁⨁◯◯ LOW 6 |

|

Mean number of days in stable housing assessed with: self‐report follow up: range 12 months to 24 months |

‐ |

SMD 0.09 SD more (0 to 1.79 more) |

‐ |

1140 (5 RCTs) |

⨁◯◯◯ |

|

Number of days in longest residence during previous 6 months assessed with: not reported follow up: 12 months |

The mean number of days in longest residence during previous 6 months was 160.9 days |

The mean number of days in longest residence during previous 6 months in the intervention group was 16,3 days fewer (CI not reported) |

‐ |

58 (1 RCT) |

⨁◯◯◯ |

|

Number of clients who did not move during previous 6 months assessed with: not reported follow up: 12 months |