Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, meiotic recombination is initiated by DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). DSBs usually occur in intergenic regions that display nuclease hypersensitivity in digests of chromatin. DSBs are distributed nonuniformly across chromosomes; on chromosome III, DSBs are concentrated in two “hot” regions, one in each chromosome arm. DSBs occur rarely in regions within about 40 kb of each telomere and in an 80-kb region in the center of the chromosome, just to the right of the centromere. We used recombination reporter inserts containing arg4 mutant alleles to show that the “cold” properties of the central DSB-deficient region are imposed on DNA inserted in the region. Cold region inserts display DSB and recombination frequencies that are substantially less than those seen with similar inserts in flanking hot regions. This occurs without apparent change in chromatin structure, as the same pattern and level of DNase I hypersensitivity is seen in chromatin of hot and cold region inserts. These data are consistent with the suggestion that features of higher-order chromosome structure or chromosome dynamics act in a target sequence-independent manner to control where recombination events initiate during meiosis.

Recombination ensures the proper segregation of homologs at the first meiotic division in most eucaryotic organisms (28, 56, 57, 60). Crossovers hold homolog pairs together, ensuring their proper alignment on the meiosis I spindle and providing the tension necessary for spindle integrity (47). Mutant cells that fail to initiate meiotic recombination display marked (and lethal) homolog nondisjunction at meiosis I (2, 12, 27, 42, 43). Even in wild-type cells, homolog pairs that fail to recombine are at increased risk for meiosis I nondisjunction (9, 22, 30, 31).

Not all crossovers are equally effective at promoting proper homolog disjunction. Human chromosomes 16 or 21 with crossovers near the telomeres are at increased risk for meiosis I nondisjunction during oogenesis (22, 31, 32); a similar phenomenon was reported in studies of the meiotic segregation of minichromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (58). These data underscore the need not only for mechanisms that control the amount of meiotic recombination per chromosome but also for control over the chromosomal location of exchange events.

Evidence that such mechanisms do exist is also inferred from observed nonuniformities in the amount of meiotic recombination per unit physical distance in a variety of organisms (36). It is likely that most of this variation is due to differences in frequencies of initiation events, although some of this variation may be due to crossover interference (24, 28). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) initiate meiotic recombination (reviewed in references 28, 36, 48, and 60). DSBs form at chromatin sites that are nuclease hypersensitive (15, 26, 50, 68). These open sites are most often found in promoter regions (21, 68) but are also found in nonpromoter regions in artificial constructs (15, 26, 67). It has been suggested that the close correlation between DSB and nuclease-hypersensitive sites reflects the preferential binding of DSB-forming proteins at places where DNA is exposed (68). Active DSB sites display an increase in micrococcal nuclease sensitivity early in meiosis I prophase, an increase that is suggested to result from the binding of DSB-forming complexes (49, 50).

DSBs also show nonuniform distributions along chromosomes. This has been documented in pulsed-field gel analyses of several yeast chromosomes (29, 39, 72). In general, the majority of DSBs occur in regions ca. 50 to 100 kb in length. These “hot” regions are separated by regions of similar size that lack DSBs. DSBs also are absent from sequences within 40 to 50 kb of telomeres (29, 39). Baudat and Nicolas (3) used conventional agarose electrophoresis to determine the location and frequency of DSBs along the entire 340 kb of chromosome III (Fig. 1). They found that the majority of detectable DSBs occur at sites in two hot regions 70 to 90 kb in length. These two domains, referred here to as hot regions II and IV, are located on the left and right arms, respectively, of chromosome III. Very few DSBs occur near the telomeres (cold regions I and V) and in a central 80-kb central region (cold region III).

FIG. 1.

Structure of the recombination construct and insert locations. (A) DSBs on chromosome III. Breaks were mapped by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of DNA prepared from MJL2305 just before (mitotic) or 6 h after (meiotic) transfer to sporulation medium. The probe used was a PCR fragment from the left end of chromosome III (nt 15838 to 16857). Positions of DSB regions I to V (3) are indicated above the autoradiogram; locations of the cold region URA3-arg4 inserts used in this study are indicated on the map of chromosome III below the autoradiogram. (B) Structure of inserts. Plasmids contain pBR322 sequences (thick line), a 1.2-kb HindIII URA3 fragment (hatched box), and a 3.3-kb PstI arg4 fragment (open box), containing either the arg4-nsp or arg4-bgl allele. Thin lines represent flanking genomic sequences used for integration, with × indicating the restriction site used for integration. Vertical arrows indicate the approximate location of DSBs seen in all inserts.

There are two possible classes of explanation for this nonuniform break distribution. The first suggests that DSBs fail to occur in cold regions because these regions lack suitable substrates for DSB formation, either by lacking potential open chromatin sites or by chromatin occlusion via silencing processes similar to those seen at telomeres and at silent mating-type cassettes (19, 66). An alternative hypothesis is that systems repress or promote DSB formation sites in cold and hot regions without affecting underlying chromatin structure (3). Sequences inserted into a hot or cold region should also be affected by such systems and therefore should display frequencies of recombination and DSBs characteristic of the region in which they are inserted. Previous studies have shown that location in the genome can affect the frequency of meiotic recombination and DSBs within a sequence (18, 35, 67, 69). However, these studies did not directly address the relationship between DSB and recombination frequencies seen within an insert and the hot or cold nature of the region where it is inserted.

We present here an examination of the mechanisms responsible for the absence of DSBs from the cold region in the center of chromosome III. We compare this region with other regions on the chromosome in terms of overall accessibility of DNA in chromatin to exogenously added DNase I and to endogenous topoisomerase II. We have examined the ability of hot and cold regions to promote or repress recombination and DSBs within recombination reporter inserts and used these inserts to define the boundaries of the central cold region. The same inserts were also used to determine the amount of crossing over that occurs within different segments of the central cold region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids.

Insert locations on chromosome III are illustrated in Fig. 1. Yeast strains and plasmids are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. All yeast strains are of the SK1 background (25). All plasmids are derived from pMJ113 or pMJ115, which contain pBR322 sequences, the URA3 gene, and arg4-nsp or arg4-bgl alleles, respectively (67). PCR fragments with added EcoRI sites were generated from yeast genomic DNA from MJL1059 (67) and cloned into the EcoRI site of pMJ113 or pMJ115. A unique site in the PCR fragment was used to linearize and integrate the resulting plasmid. Integration sites were chosen to reside in intergenic regions, preferably between the 3′ ends of two genes. pMJ113- and pMJ115-derived plasmid integrants were obtained by transformation of S105 (MATa ura3 lys2 ho::LYS2 leu2-R arg4-nsp,bgl) and S95 (MATα ura3 lys2 ho::LYS2 leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl), respectively (67). Insert-containing haploid parents of rad50S diploid strains were obtained by tetrad dissection of diploids formed by crossing insert-containing RAD50 haploids with a haploid parent of NKY1002 (7). The sae2Δ::KanMX6 mutation contains a SacI-SmaI fragment from pFA6 (64) encoding G418 resistance inserted between the SacI and EcoRV sites of SAE2 (nucleotides [nt] 60 and 643 of the SAE2 open reading frame).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used

| Strain | Genotypea |

|---|---|

| For chromatin and topoisomerase II studies | |

| MJL1578 | leu2-Karg4-bglnuc1Δ::LEU2 |

| leu2 arg4-bgl nuc1Δ::LEU2 | |

| MJL2418 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglhis4::URA3-(arg4-nsp)RVS161 |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl HIS4 RVS161::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| For random spore analysis | |

| MJL2081 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglRVS161::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl RVS161::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| MJL2082 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglYCR026c::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl YCR026c::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| MJL2083 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglRIM1::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl RIM1::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| MJL2142, MJL2143 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglYCR004c::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl YCR004c::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| MJL2229, MJL2230 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglYCR017c::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl YCR017c::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| MJL2033, MJL2034 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglycl11c::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl ycl11c::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| For DSB quantitation | |

| MJL2305 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglsae2::KanMX6 |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl sae2::KanMX6 | |

| MJL1170 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglhis4::URA3-(arg4-nsp)rad50-KI81::URA3 |

| leu2-R ARG4 his4::URA3-(arg4-nsp) rad50-KI81::URA3 | |

| MJL1185 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglMATa::URA3-(arg4-nsp)rad50-KI81::URA3 |

| LEU2 ARG4 MATα rad50-KI81::URA3 | |

| MJL1185 | leu2-RHML-proximal::URA3-(arg4-nsp)rad50-KI81::URA3 |

| LEU2 HML-proximal rad50-KI81::URA3 | |

| MJL2105 | Same as MJL2081, but rad50-KI81::URA3 |

| MJL2106 | Same as MJL2083, but rad50-KI81::URA3 |

| MJL2139 | Same as MJL2082, but rad50-KI81::URA3 |

| MJL2144 | Same as MJL2142, but rad50-KI81::URA3 |

| MJL2237 | Same as MJL2229, but rad50-KI81::URA3 |

| MJL2324 | Same as MJL2033, but sae2::KanMX6 |

| MJL2326 | arg4-nsp,bglleu2::URA3-(arg4-nsp)sae2::KanMX6 |

| arg4-nsp,bgl leu2::URA3-(arg4-bgl) sae2::KanMX6 | |

| MJL2420 | Same as MJL2418, but rad50-KI81::URA3 |

| For measuring genetic distances | |

| MJL1915 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglTRP1 |

| LEU2 ARG4 trp1::hisG | |

| MJL2437, MJL2438 | LEU2 ARG4trp1::hisG |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl TRP1 | |

| MJL2109 | LEU2ARG4trp1::hisGRVS161 |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl TRP1 RVS161::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| MJL2111 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglTRP1RVS161::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| LEU2 ARG4 trp1::hisG RVS161 | |

| MJL2113 | LEU2ARG4trp1::hisGYCR026c |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl TRP1 YCR026c::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| MJL2124 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglTRP1YCR026c::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| LEU2 ARG4 trp1::hisG YCR026c | |

| MJL2115 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglTRP1RIM1::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| LEU2 ARG4 trp1::hisG RIM1 | |

| MJL2125 | LEU2ARG4trp1::hisGRIM1 |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl TRP1 RIM1::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| MJL2186 | LEU2ARG4trp1::hisGYCR017c |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl TRP1 YCR017c::URA3-(arg4-bgl) | |

| MJL2187, MJL2188 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglTRP1YCR017c::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| LEU2 ARG4 trp1::hisG YCR017c | |

| MJL2424, MJL2425 | leu2-Rarg4-nsp,bglTRP1MATa::URA3-(arg4-nsp) |

| LEU2 ARG4 trp1::hisG MATα | |

| MJL2426, MJL2427 | LEU2ARG4trp1::hisGMATa |

| leu2-K arg4-nsp,bgl TRP1 MATα::URA3-(arg4-bgl) |

All strains are homozygous for ura3, lys2, and ho::LYS2; all except MJL1578 (37), MJL1170, MJL1176, and MJL1185 (67) were constructed for this work. The MATa parent of each diploid represented above the line. arg4 and leu2 without a specific allele indicate that the mutant allele has not been determined. Structure of the URA3-arg4 insert is depicted in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

URA3-arg4 plasmids

| Plasmid namesa | Locus | Fragment coordinatesb | Integration sitec |

|---|---|---|---|

| pMJ462 and pMJ349 | YCL011c | 101706–103145 | 102553 (AflII) |

| pMJ508 and pMJ510 | YCR004c | 118532–119248 | 118810 (AflII) |

| pMJ481 and pMJ484 | RVS161 | 129959–130492 | 130199 (SacII) |

| pMJ514 and pMJ520 | YCR017c | 144280–144630 | 144409 (AflII) |

| pMJ482 and pMJ485 | YCR026c | 163445–164151 | 163812 (AflII) |

| pMJ483 and pMJ486 | RIM1 | 171197–172008 | 171587 (SphI) |

Plasmids are derived from pMJ113 (arg4-nsp) and pMJ115 (arg4-bgl), respectively (67).

Coordinates on chromosome III (51) of the locus-specific fragment used to direct integration. In all cases, this fragment was inserted at the pBR322 EcoRI site (see Materials and Methods).

Chromosome III coordinate of integration site and restriction enzyme used to direct integration.

Media and genetic techniques.

Standard methods and media were used for growth and mating. Transformation of strains was done as described elsewhere (4). Meiotic segregants were analyzed either by tetrad dissection or by random spore analysis (35). Linkage and centromere linkage analysis was done as described elsewhere, using TRP1 as a centromere-linked marker (46). For sae2::KanMX transformants, cells were grown for 4 h after transformation in YPD containing 1 M sorbitol before selecting on YPD plates containing 1 M sorbitol and 400 μg of G418 (Gibco/BRL) per ml. Sporulation in liquid cultures was as described elsewhere (20).

DSB detection.

Meiotic DSBs were detected in diploids homozygous for either rad50KI80 (rad50S) or sae2::KanMX. In both types of strains, meiotic DSBs are not resected after formation (1, 41, 53). Meiotic DNA was prepared 6 to 7 h after the initiation of sporulation. For conventional gel electrophoresis, DNA was prepared as described elsewhere (20) except that cells were rapidly spheroplasted in 1 M sorbitol–10 mM EDTA–50 mM potassium phosphate–1 mg of lyticase (ICN) per ml (pH 7.5), and DNA was prepared immediately after harvesting of cells. Previous DNA extraction methods used cells that had been fixed in ethanol (7). In DNA from such cells, some meiosis-specific DSBs seen in the insert were stronger than in DNA prepared immediately after harvesting of cells. This is most likely due to the action of Nuc1p, a mitochondrial nuclease that is released upon storage in ethanol (10). For pulsed-field gel analysis of DSBs, 50-ml aliquots of a premeiotic or meiotic culture (about 2 × 109 cells) were washed three times with 50 mM EDTA (pH 7.5) at room temperature and resuspended with 0.33 ml of 50 mM EDTA; 0.5 ml of this suspension was mixed with 1 ml of 0.83% low-melting-point agarose (FMC)–170 mM sorbitol–17 mM sodium citrate–10 mM EDTA–0.85% β-mercaptoethanol–0.17 mg of Zymolase 100T (ICN) per ml (pH 7.0), poured into molds, and allowed to solidify for 10 min at 4°C. Plugs were incubated as follows: 2 h at 37°C in 10 ml of 450 mM EDTA–10 mM Tris-HCl–7.5% β-mercaptoethanol–0.1 μg of RNase A per ml (pH 7.5); overnight at 50°C in 10 ml of 450 mM EDTA–10 mM Tris-HCl–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–1 mg of proteinase K per ml (pH 7.5); two changes of 10 ml of 50 mM EDTA (pH 7.5) for 30 min at room temperature. Plugs were stored at −20°C in 10 ml of 50 mM EDTA–50% glycerol (pH 7.5). As a control for general DSB formation, we checked in each strain that DSBs occurred at the normal arg4 locus on chromosome VIII at normal frequencies (68). The average frequency at this locus was 4% ± 0.7% (data not shown).

DNase I-hypersensitive and topoisomerase II cleavage site mapping.

The protocol of Wu and Lichten (68) was used. For mitotic cells, exponential-phase cultures grown in YPD (optical density at 600 nm of 1) were used. For meiotic cells, we used the SPS preculture (0 h) and cultures 2 or 4 h after transfer to sporulation medium. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1/10 the original culture volume of 1 M sorbitol–50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5)–10 mM MgCl2–1% β-mercaptoethanol–0.4 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. After 5 min of incubation at 30°C, cells were pelleted and resuspended in an equal volume of 1 M sorbitol–25 mM potassium phosphate–25 mM sodium succinate (pH 5.5)–10 mM MgCl2–0.3% β-mercaptoethanol–0.4 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.67 mg of Zymolase 100T (ICN) per ml and incubated at 30°C for 3 to 5 min. Spheroplast formation was monitored by microscope until cells were 80 to 90% spheroplasts. Crude nuclei were prepared and digested with DNase I as described elsewhere (68) except that in the pulsed-field gel experiments, a prepared cocktail of protease inhibitors (Complete, EDTA-free; Boehringer) was used, and DNase digests were for 2 min at 0°C. For pulsed-field gel analysis, 2 volumes of 1% low-melting-point agarose–50 mM EDTA pH 7.5 was added to digests, and the mixture was poured into molds and allowed to harden for 10 min at 4°C. Plugs were then processed as described above. For topoisomerase II cleavage, crude nuclei were resuspended in topo II buffer (6), VM26 (stock solution 10 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide; a gift from Yves Pommier) or CP-115.953 (stock solution 5 mM in 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]; kindly provided by Pfizer Inc.) was added to the desired concentration, and mixtures were incubated 30 min at 30°C. Two volumes of 1% low-melting-point agarose in topo II buffer plus drug was added, and reaction mixtures were poured into molds and allowed to harden 10 min at room temperature. Plugs were then soaked for 2 h at room temperature in 1% SDS and then treated with proteinase K and processed as described above.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Agarose plugs were equilibrated against 1 ml of 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (59) for 10 min at room temperature. Electrophoresis was performed at 14°C in a CHEF Mapper (Bio-Rad), using 1.3% agarose gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA, a voltage gradient of 6 V/cm, a switch angle 120°, and switch times of 15 s (initial) to 25 s (final). Total run time was 43 h.

DNA transfer and hybridization.

Electrophoresis, transfer to Zetaprobe GT membranes (Bio-Rad), and hybridization with probe were as previously described (67). A Fuji Bas2000 phosphorimager and MacBAS software were used for image capture and DSB quantitation.

RESULTS

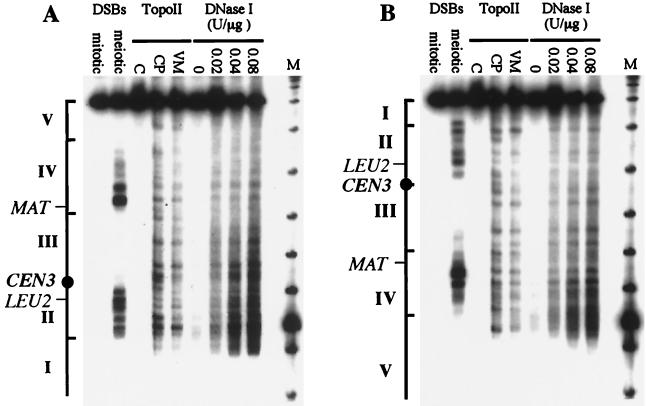

Cold and hot regions show similar patterns of chromatin accessibility to both DNaseI and endogenous topoisomerase II.

One way to account for the different levels of DSBs seen in different regions of chromosome III would be to assume that cold regions contain mostly closed chromatin and therefore are inaccessible to DSB-forming proteins. To test this, we examined the accessibility of chromatin along the length of chromosome III, using cleavage of chromatin from vegetative cells either by an exogenously added enzyme, DNase I, or by an endogenous yeast enzyme, topoisomerase II. Topoisomerase II cleavage sites were mapped by using two drugs (CP-115,953 and VM26) that trap covalently linked topoisomerase II-DNA complexes (13, 38). These complexes are converted to permanent breaks by treatment with SDS and protease (38). Pulsed-field gel analysis was used to compare DNase I and topoisomerase II cleavage patterns with those of DSBs. Pulsed-field gels have the advantage of allowing the visualization of break or cleavage patterns along the entire length of a chromosome. The resolution of this method is limited, however, and frequently what appears to be a single band on a pulsed-field gel reflects the presence of multiple cleavage sites distributed over a region several kilobases in length.

Similar results were obtained with DNase I and with the two topoisomerase II inhibitors (Fig. 2). DNase I and topoisomerase II cleavage sites are distributed irregularly along the chromosome, with no obvious concentration in any region. In particular, the central cold region (III) and the two terminal cold regions (I and V) are cleaved as often as are hot regions II and IV. There is a substantial correspondence between DNase I and topoisomerase II cleavage patterns, as would be expected if both enzymes act preferentially in open regions of chromatin. In hot regions II and IV, this correspondence extends to the location of DSB peaks as well. We conclude that the three cold regions do not differ from the hot regions in terms of chromatin accessibility and that the cold regions would therefore be expected to contain many potential DSB sites.

FIG. 2.

Chromatin structure and topoisomerase II cleavage of mitotic chromosome III. Mitotic and meiotic rad50S samples are from MJL2305, 0 and 6 h, respectively, after transfer to sporulation medium. Chromatin was prepared from exponentially growing cells of strain MJL1578. For topoisomerase II (TopoII) cleavage sites, chromatin was incubated with 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (C), 100 μM CP-115,953 (CP), or 100 μM VM26 (VM); for DNase I-sensitive sites, chromatin was incubated with the indicated concentration of DNase I (U/μg of DNA). DNA was displayed on a pulsed-field gel (see Materials and Methods), and the resulting filter was probed with a CHA1 probe (chromosome III nt 15838 to 16857) (A) or a YCR098c probe (nt 296511 to 297070) (B). Lanes M contain bacteriophage λ DNA concatemers plus a HindIII digest of bacteriophage λ. The hot or cold DSB regions I to V are indicated alongside each panel.

Meiotic recombination within a recombination reporter construct is governed by chromosomal context.

If cold regions I, III, and V contain potential DSB sites, what prevents the formation of DSBs at those sites? One explanation is that open sites present in these regions contain sequences refractory to DSB formation. An alternate explanation is that factors necessary for DSBs are absent from cold regions, or that systems operate in cold regions to actively suppress DSB formation. In either of the latter cases, it might be expected that DSB formation would be affected not only in sequences normally resident in cold regions but also in sequences inserted within the same regions.

To test this, we measured both meiotic recombination and DSBs in a recombination reporter construct inserted at several locations on chromosome III (Fig. 1). This 8.5-kb construct contains the URA3 gene as a selectable marker and an ARG4 fragment marked with either of two arg4 mutant alleles (Fig. 1B). A previous study showed that both recombination and DSBs within this construct display position effects: they are affected in parallel by the location of inserts in the genome (67). In the present study, we examined meiotic recombination and DSBs in 10 inserts on chromosome III. One insert is in the left-arm terminal cold region I (at CHA1), three are in the left-arm hot region II (at HIS4, LEU2, and YCL011c), five are in the central cold region III (YCR004c, RVS161, YCR017c, YCR026c, and RIM1), and one is at MAT, in the right-arm hot region IV (Fig. 1A). Four of these insert loci had been studied previously (20, 67); the others were constructed for the present study.

Recombination at each insert locus was measured by determining frequencies of Arg+ spores produced by meiotic recombination between arg4-nsp and arg4-bgl inserts at allelic locations. Arg+ frequencies varied over a 15-fold range, from 1.2 × 10−3 to 1.9 × 10−2 (Table 3). All inserts in cold regions I or III produced recombinants at frequencies that were less than those seen for inserts in hot regions. Among cold region inserts, the lowest recombination frequencies were obtained with inserts closest to CEN3 (RVS161::arg4, 1.2 × 10−3; YCR004c::arg4, 1.7 × 10−3), and the greatest recombination frequency (7.0 × 10−3) was obtained with RIM1::arg4, the cold region insert furthest from the centromere. We did not detect a discrete boundary between cold region III and hot region IV; instead, frequencies of Arg+ recombinants increased gradually with insert distance from the centromere. For example, the frequency of Arg+ recombinants from diploids with the cold region III insert RIM1::arg4 (7.0 × 10−3) was similar to that seen in MAT::arg4 strains (9.4 × 10−3); this latter insert is 26 kb more centromere distal and well within hot region IV. By contrast, there appears to be a much sharper boundary between cold region III and hot region II. Strains with YCL011c::arg4 inserts, located to the left of CEN3 in hot region II, display a frequency of Arg+ recombinants (1.0 × 10−2) sixfold greater than that seen in strains with inserts only 16 kb away, at YCR004c (1.7 × 10−3).

TABLE 3.

Frequency of recombination and DSBs in URA3-arg4 inserts

| Insert location | f(ARG4)a (103) | DSB frequency (%)b

|

ARG4/ DSB ratioc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSB-left | DSB-right | DSB-total | |||

| CHA1 | 4.7 ± 0.3d | 1.2 ± 0.1 (4) | 2.0 ± 0.6 (3) | 3.2 | 0.15 |

| HIS4 | 17 ± 1.7d | 13 ± 1.8 (5) | 3.5 ± 0.2 (5) | 16.5 | 0.10 |

| LEU2 | 19 ± 0.7d | 7.8 ± 0.1 (2) | 6.4 (1) | 14.2 | 0.13 |

| YCL011c | 10 ± 2.1 | 8.2 ± 1.3 (3) | 2.4 ± 0.7 (3) | 10.6 | 0.11 |

| YCR004c | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.3 (7) | 1.0 ± 0.01 (2) | 2.8 | 0.06 |

| RVS161 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.15 (6) | 1.4 ± 0.5 (5) | 1.9 | 0.06 |

| YCR017c | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.13 (3) | 1.9 ± 0.6 (4) | 2.8 | 0.09 |

| YCR026c | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 (3) | 2.7 ± 0.4 (3) | 4.3 | 0.08 |

| RIM1 | 7.0 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.8 (5) | 2.9 ± 0.7 (3) | 5.4 | 0.12 |

| MAT | 9.4 ± 2.7 | 6.0 ± 0.01 (2) | 4.2 ± 0.6 (3) | 10.2 | 0.09 |

ARG4 spores/total spores ± standard deviation.

DSBs/chromosome ± standard deviation (no. of determinations).

Ratio of frequencies in second and fifth columns.

Data from Wu and Lichten (67).

We also measured the frequency of recombination between the leu2-K and leu2-R alleles as a general control. With two exceptions, all strains displayed similar frequencies of Leu+ meiotic recombinants (mean = 4.0 × 10−3; greatest deviation = 0.5 × 10−3). Inserts at HIS4 and at YCL011c caused a significant (about 2.5-fold) reduction in the frequency of Leu+ recombinants recovered, most likely a result of an insert-dependent local inhibition of DSBs at nearby sites (67, 70).

The frequency of DSBs within inserts is governed by chromosomal context.

If most events producing Arg+ recombinants are initiated by DSBs that form within insert sequences, the frequency of breaks in URA3-arg4 inserts should display position effects similar to those seen for meiotic recombination frequencies. To test this suggestion, we determined the location and frequency of DSBs within the URA3-arg4 inserts used to measure recombination, using otherwise isogenic rad50S or sae2 strains. As was seen previously (67), DSBs occur at the same place within inserts at all loci (illustrated in Fig. 1). One group of breaks (DSB-left) is located in pBR322 sequences, between URA3 and arg4. A second group of breaks (DSB-right) is located in a 1.8-kb pBR322 region just to the right of arg4 sequences. Breaks at the insert-borne arg4 promoter are either absent or barely detectable. By contrast, the normal ARG4 locus displays strong breaks in its promoter region in all strains (data not shown); these breaks occur in 4.0 ± 0.7% of chromosomes, a value in good agreement with that seen for strains without inserts (67).

To quantitatively compare DSB frequencies in different inserts, we used restriction enzymes that cut at sites common to all inserts and probed blots with pBR322 fragments (Fig. 3 and Table 3). Quantitative analysis indicates that the total frequency of DSBs within inserts increases in parallel with the frequency of ARG4 recombinants (Table 3; Fig. 4). Overall, there is an almost 10-fold variation in the frequency of breaks within inserts, from 1.9% at RVS161::arg4 to 16.5% at his4::arg4, and inserts in cold regions display break frequencies significantly less than those in hot regions. Thus, DSB position effects are exerted in a target sequence-independent manner.

FIG. 3.

DSBs in inserts at different locations on chromosome III detected by using pBR322 sequences as probes. (A) DSBs between URA3 and arg4 sequences (DSB-left). DNA was digested with PstI (P), which cuts in pBR322 and in URA3, and probed with a PstI-AlwNI fragment from pBR322. DSB-left is indicated by a solid arrow, and the ARG4 promoter (prom.) is indicated by a dotted arrow. Mitotic DNA is from MJL2105. Meiotic DNAs are, from left to right: MJL2105, MJL2144, MJL2237, MJL1185, MJL2139, MJL2106, MJL1176, MJL1170, MJL2324, and MJL2326. (B) DSBs in the pBR322 sequence downstream of the arg4 fragment (DSB-right). DNA was cut with StuI (St) and a locus-specific enzyme: RSV161, SacII; YCR004c, AflII; YCR017c, AflII; CHA1, XhoI; YCR026c, AflII; RIM1, SphI; MAT, XbaI; YCL011c, AflII; LEU2, AflII; and HIS4, Bpu1102I. The probe used was a HindIII-BamHI pBR322 fragment. DSB-right is indicated by solid arrows and the ARG4 promoter is indicated by a dotted arrow. Mitotic DNA is from MJL2105. Meiotic DNAs are, from left to right: MJL2105, MJL2144, MJL2237, MJL2139, MJL1185, MJL1176, MJL2324, MJL2326, and MJL1170.

FIG. 4.

Frequencies of DSBs and recombination within URA3-arg4 inserts. Chromosome III DSB hot and cold regions are indicated. The thick horizontal lines denote a physical map of chromosome III, with 50-kb intervals indicated by vertical hatches and the centromere marked by a filled circle. Bars in the top panel indicate the frequency of Arg+ recombinants within each insert (hatched bars); bars in the bottom panel indicate the frequencies of both DSB-left (shaded) and DSBs-right (white) for inserts at the same location. Recombination data for inserts at MAT, CHA1, LEU2, and HIS4 are from a previous study (67).

As was seen with Arg+ recombinants, insert DSB frequencies increase gradually with distance from the centromere at the right-hand boundary of cold region III and increase more abruptly at the left-hand cold region boundary. However, the magnitude of position effects is not the same at DSB-left and DSB-right. Among cold region inserts, the frequency of breaks at DSB-left varies 5-fold, from 0.47% (RVS161::arg4) to 2.5% (RIM1::arg4); a 30-fold variation is observed among all inserts on chromosome III. The frequency of breaks at DSB-right is less affected by insert location, showing only a twofold variation among inserts in the cold region (1.4% at RVS161 to 2.9% at RIM1) and about a sixfold variation overall. Moreover, there are marked differences in the ratio of break frequencies at DSB-left and DSB-right within an insert (Table 3). At one extreme, his4::arg4, breaks at DSB-left exceed breaks at DSB-right by a factor of 3.7; at the other, RVS161::arg4, the ratio of breaks at DSB-left to DSB-right is 0.36.

Both hot and cold region inserts display similar patterns and levels of chromatin DNase I sensitivity.

The finding that URA3-arg4 inserts take on the recombination/DSB properties of the region in which they reside makes it unlikely that underlying DNA sequence is responsible for differences between hot and cold regions. However, it remained possible that differences in chromatin structure were responsible for the differences in recombination and DSB frequencies seen in hot and cold region inserts. To test this suggestion, we quantitatively compared the pattern and level of DNase I sensitivity of a hot region insert with those of a cold region insert. This was done by using chromatin prepared from a diploid strain in which one copy of chromosome III contained a his4::URA3-arg4 insert in hot region IV and the other chromosome copy contained the cold region insert RVS161::URA3-arg4 (Fig. 5A). The presence of unique restriction sites flanking each insert, combined with locus-specific probes, allowed the detection of DSBs or DNase I-hypersensitive sites in the hot and cold region inserts by sequential probing of the same membrane. This permitted direct quantitative comparison of the extent of DNase I hypersensitivity in hot and cold region inserts.

FIG. 5.

DNase I-hypersensitive sites in the URA3-arg4 insert at HIS4 and RVS161. (A) Location of the URA3-arg4 insert on each chromosome III of strain MJL2418. (B) DSBs and DNase I-hypersensitive sites in inserts. DNA was cut with both AflII and XbaI, and the same filter was probed successively with an RVS161 probe (nt 128743 to 129300; left) and a HIS4 probe (nt 65967 to 66522; right). For DNase I, chromatin from MJL2418 was prepared at indicated times after transfer to sporulation medium and incubated with DNase I. Lanes: 1, 4, and 6, no DNase I; 2 and 5: 0.8 U of DNase I/μg of DNA; 3, 0.8 U of DNase I/μg of DNA; 7, 2 U of DNase I/μg of DNA. For rad50S DSBs, DNA from MJL2420 0 h (lanes 9) or 6 h (lanes 8) after transfer to sporulation medium. (C) Quantitative comparison of DNase I digestion profiles of URA3-arg4 inserts located at either RVS161 (thin lines) or HIS4 (thick lines). Densitometric profiles of lanes 3 (0 h), 5 (2 h), and 7 (4 h) are superimposed.

DSB locations and frequencies at each insert locus, measured in a rad50S derivative of this strain, are similar to those observed in diploids with homozygous inserts at one or at the other locus (Fig. 5B and data not shown). This finding confirms previous conclusions that DSB formation is not markedly affected by the presence or absence of a homologous sequence at an allelic position on a homologue (11, 17, 67). DSBs occurred frequently at his4::URA3-arg4 and infrequently at RVS161::URA3-arg4. By contrast, the two inserts display similar patterns of DNase I sensitivity in chromatin isolated from RAD50 cultures before (0 and 2 h) and after (4 h) the time of DSB formation. DNase I-hypersensitive sites are present at the arg4 promoter and at the same locations as DSB-left and DSB-right (Fig. 5B). Quantitative comparison revealed similar levels of DNase I hypersensitivity at his4::URA3-arg4 and at RVS161::URA3-arg4 in chromatin samples taken at 0 and 2 h (Fig. 5C). Resected DSBs were present in his4::URA3-arg4 in chromatin isolated at 4 h but not in RVS161::URA3-arg4 chromatin (Fig. 5B), thus precluding meaningful comparisons between the two insert loci in this sample.

Crossing over is reduced in the central cold region.

The consensus genetic map of chromosome III (45) indicates that crossovers rarely occur in the genetic interval between CEN3 and PGK1, loci that define the left-hand (centromere-proximal) half of the central cold region. This low crossover density (0.08 centimorgan [cM]/kb) is consistent with the absence of detectable DSBs in this region (Fig. 1 and reference 3). By contrast, the consensus map distance between the two cold region markers PGK1 and CRY1 is 24 cM (0.6 cM/kb). These two loci define the right-hand (centromere-distal) half of the cold region. Baudat and Nicolas report that only 2% of chromosomes suffer DSBs in this region (3). These two values are inconsistent; if all crossovers in the PGK1-CRY1 interval were initiated by the DSBs detected by Baudat and Nicolas, then this interval would be expected to have a genetic length of only 2 to 4 cM.

One possible explanation for the observed map distance/DSB discrepancy in the central cold region is that genetic distances in this region are greater in the consensus map than they are in SK1, the genetic background used by us and by Baudat and Nicolas. To test this, we constructed a fine structure genetic genetic map of the CEN3-MAT interval, using diploid strains heterozygous for LEU2, the various URA3::arg4 constructs, and the centromere-linked gene TRP1 (Table 4). We found the genetic distance between CEN3 and LEU2 to be 8.3 ± 1.0 cM, a crossover density similar to the average seen across the yeast genome (0.35 cM/kb versus 0.33 cM/kb [46]) but significantly greater than the distance given in the consensus genetic map (about 3 cM [44]). Crossovers occurred in the central cold region at a frequency significantly less than that expected from the consensus genetic map. For example, we found the genetic distance between CEN3 and RIM1::URA3, our most centromere-distal marker in the central cold region, to be about 7.5 cM, or 0.12 cM/kb (Table 4; Fig. 6), a value significantly less than the consensus map distances between the centromere and PET18 or CRY1, the two markers on the consensus map closest to RIM1 (about 17 and 25 cM, respectively).

TABLE 4.

Genetic distances in the central cold region of chromosome IIIa

| Insert location |

LEU2-CEN3

|

CEN3-insert

|

Insert-MAT

|

LEU2-insert

|

CEN3-MAT

|

LEU2-MAT

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDS | SDS | cM | FDS | SDS | cM | PD | T | NPD | cM | PD | T | NPD | cM | FDS | SDS | cM | PD | T | NPD | cM | |

| RVS161 | 157 | 25 | 7.3 | 193 | 2 | 0.4 | 145 | 47 | 1 | 14 | 159 | 23 | 0 | 6.3 | 144 | 49 | 13 | 120 | 57 | 4 | 22 |

| YCR017c | 125 | 24 | 8.9 | 148 | 12 | 4.2 | 124 | 36 | 0 | 11 | 121 | 29 | 0 | 9.7 | 118 | 41 | 13 | 103 | 48 | 1 | 18 |

| YCR026c | 158 | 29 | 8.4 | 174 | 23 | 6.3 | 167 | 29 | 1 | 8.9 | 143 | 44 | 0 | 12 | 152 | 46 | 12 | 121 | 64 | 2 | 20 |

| RIM1 | 151 | 34 | 10 | 168 | 27 | 7.5 | 170 | 24 | 0 | 6.2 | 131 | 53 | 1 | 16 | 147 | 47 | 13 | 116 | 65 | 3 | 23 |

| MAT | 72 | 11 | 7.2 | 67 | 21 | 12 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 54 | 29 | 1 | 21 | 67 | 21 | 12 | 54 | 29 | 0 | 21 |

| No insert | 124 | 23 | 8.2 | 104 | 54 | 19 | 123 | 80 | 3 | 24 | |||||||||||

Recombinants between inserts and other markers were detected using the URA3 gene of the insert. Genetic distances were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. FDS, first-division segregation; SDS, second-division segregation; PD, parental ditype; NPD, nonparental ditype; T, tetratype.

FIG. 6.

Crossing over within cold region III. For each insert, genetic distances are presented above the line, and crossover densities are given below. The location of each URA3-arg4 insert used for measuring genetic distances, as well as the position of CEN3, is shown on the chromosome III map.

The lowest crossover density was seen in the 16-kb interval immediately to the right of the centromere, between CEN3 and RVS161::URA3 (0.4 cM, or 0.02 cM/kb). Crossovers between CEN3 and YCR017c::URA3 were much more frequent, with 4.2 cM in this 30-kb interval (0.14 cM/kb), and the crossover density remained relatively constant for larger CEN3-insert intervals (0.11 cM/kb for CEN3-YCR026c::URA3; 0.12 cM/kb for CEN3-RIM1::URA3). Thus, it appears that crossing over is strongly suppressed only in the most centromere-proximal quarter of the cold region. Consistent with this conclusion is the observation that insert-MAT crossover densities were similar for all cold region inserts examined (0.16 ± 0.014 cM/kb).

General applicability of these data may be limited by an unanticipated effect on crossing over of the hemizygous URA3-arg4 inserts. The average genetic distance between CEN3 and MAT in insert-bearing strains (12.8 ± 0.5 cM) is significantly less than the distance observed (19 cM) in two isogenic strains with no construct in this interval (Table 4 and Fig. 6). To test the possibility that the sequence heterology introduced by the hemizygous insert is responsible for this loss of crossovers, we measured the CEN3-MAT genetic distance in a strain with a MAT::URA3 insert. This insert duplicates the MAT locus (67) and thus lies outside the CEN3-MAT genetic interval. The genetic distance between CEN3 and MAT was 12 cM in these strains as well. Therefore, the reduction in crossing over seen in CEN3-MAT is a direct consequence of the presence of an insert in the vicinity of the interval, rather than of the introduction of heterology.

DISCUSSION

Meiotic recombination events are not uniformly distributed along chromosomes (reviewed in reference 36). In S. cerevisiae, meiotic DSBs appear to be clustered into hot regions and absent from the ends of chromosomes and from internal cold regions (3, 29, 39, 72). Our experimental approach has allowed us to examine the reasons for this clustering. The recombination reporter construct used as a target contains the same DNA sequence and most likely adopts the same chromatin structure at each insert location (reference 67 and this work). In a previous study, we showed that both DSBs and intragenic recombination in this reporter construct display position effects (67). In the present study, we further examined this phenomenon by inserting the construct at many sites along chromosome III. We found that the factors making regions hot or cold for DSBs and recombination do act in a way that is target sequence independent. However, our data also indicate that there is a subregion inside the central cold region of chromosome III where breaks are normally absent, but will form if a proper substrate is provided.

What makes the hot regions hot and the cold regions cold?

The hypothesis that chromatin in cold regions might be closed to access by DSB-forming complexes or by other factors that cleave DNA in chromatin does not appear to be true, at least at the level of sensitivity offered by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis of DNase I and topoisomerase II digests of chromatin. We found the cold and hot regions of chromosome III are similarly accessible both to exogenously added DNase I and to endogenous topoisomerase II, using either of two inhibitors. In addition, two copies of the URA3-arg4 insert, one in a hot region and the other in a cold region, display quantitatively similar patterns and levels of DNase I hypersensitivity in chromatin isolated from mitotic cells and from meiotic cells before and during the time of DSB formation. It is therefore unlikely that the central cold region of chromosome III lacks DSBs because of a general occlusion of chromatin akin to what is seen at telomeres and in mating-type cassettes (19, 66). Our results also underscore previous conclusions that open chromatin is a prerequisite but in itself is not sufficient for DSB formation (15, 67).

We believe that our data, obtained by in vitro digests of chromatin, reflect the general accessibility of chromatin in vivo; the conditions that we used in topoisomerase II studies have been shown in other organisms to produce cleavage patterns similar to those seen in living cells (6, 62). However, we cannot exclude the possibility of the loss during chromatin preparation of nonnucleosomal features of chromatin, perhaps induced during meiosis, that are responsible for the absence of DSBs from cold regions.

If the cold region is not cold due to the occlusion of potential DSBs sites, are general factors acting over the cold and hot regions to specifically repress or promote DSB formation? Our main result, that the total frequency of DSBs within inserts is increased in hot regions and reduced in cold region inserts, would certainly suggest that this is the case. The total frequency of insert DSBs parallels the frequency of recombination in the insert, suggesting that in the construct, most events yielding Arg+ recombinants are initiated by DSBs formed within insert sequences. However, detailed features of the data may reflect the presence of local influences. Position effects are not always the same at DSB-left and DSB-right. This may reflect competition for DSB-forming factors between DSB-left, DSB-right, and the native DSB sites present to each side of the insert (16, 67, 71). These local effects may also reflect the possibility that DSB-left and DSB-right occupy different positions on a gradient of break-forming activity, especially at the boundary between hot and cold domains.

Our data point to the existence of hot and cold DSB domains that act in a local sequence-independent manner but do not directly address the systems that confer hot and cold properties upon a region. There are many possible explanations for the existence of these domains, including features of higher-order chromosome structure such as differential chromatin compaction or region-specific localization within the nucleus. The latter might result from the attachment of the telomeres to the nuclear periphery and the organized movement of centromeres and telomeres that occur before and during the time of DSB formation (8, 61). If DSB-forming factors are distributed nonuniformly throughout the nucleus, these movements might partition different chromosomal domains to specific nuclear zones, thus creating hot and cold domains. With regard to this suggestion, it is interesting that each of the three cold domains on chromosome III is associated with either a telomere or a centromere. Testing the generality of this association will require analysis of DSB patterns on other chromosomes at a greater resolution than is afforded by current pulsed-field gel-based studies. Alternatively, DSB-forming factors may be loaded onto chromosomes during premeiotic DNA replication, in a manner similar to that seen for mitotic and meiotic sister chromatid cohesins (63, 65), thus favoring early-replicating regions for DSB formation. Indeed, both chromosome III hot regions contain origins that fire early in mitotic S phase (3, 55). Moreover, a weak meiotic recombination hot spot is associated with ARS307, an origin located in the left-arm hot region (54).

What defines the boundaries of the cold and hot regions?

Since the URA3-arg4 construct reveals the potential of a chromosomal region to form DSBs, our results can be used to redefine the boundaries of the central cold region. Our data indicate that there is no precise boundary between the central cold region and hot region IV. This is in contrast to the sharp boundary seen for DSBs in native sequences (3). To account for this apparent discrepancy, we suggest that the centromere-distal part of the central cold region contains native sequences and/or chromatin structures that are poor substrates for DSB formation, while the recombination-reporter construct contains sequences and/or chromatin structures more favorable for DSB formation. These inserts are therefore able to be cleaved by the DSB factors present in but normally unable to act, due to a lack of suitable substrate. If this suggestion is correct, then the actual central region in which DSBs cannot occur may be significantly shorter than the 80-kb length suggested by studies of native DSBs.

By contrast, the left-hand boundary of the central cold region is very steep. Inserts to either side of the centromere (at YCL011c and at YCR004c) display about a sixfold difference in recombination frequencies and a fourfold difference in DSB frequencies. This is in general agreement with the published DSB map (3), which shows a well-defined boundary between the left-arm hot region and the central cold region located at or near the centromere. We do not know whether the centromere itself forms the boundary between these two regions. An intriguing possible way for the centromere to limit meiotic recombination is suggested by an examination of Arg+/insert DSB ratios. The two inserts with the least Arg+/DSB ratio are those closest to the centromere, at YCR004c and at RVS161. It was shown previously that CEN3 represses both gene conversion and crossing over in its vicinity (33, 34). Our data raise the possibility that this repression comes at a stage after initiation, perhaps because specialized centromere-specific sister chromatid cohesion structures (5, 44) channel initiation events toward intersister rather than interhomolog repair.

What initiates recombination in the central cold region?

Crossing over occurs at significant frequencies in the central cold region, which is substantially free of DSBs. This discrepancy was first remarked upon by Baudat and Nicolas, comparing the consensus genetic map with the level of DSBs detected in this region (3). Although the genetic length of the cold region is significantly less in our strain background, it is still significantly greater than would be expected if crossovers were initiated exclusively by the DSBs detected in this region. An analogous discrepancy was reported by Fan et al., who found that mutants eliminating DSBs in the HIS4 promoter region still retained a significant basal frequency of gene conversion in the gene (14).

It was suggested that DSBs in the cold region are dispersed at many sites and thus fall below the level of detection on conventional Southern blots (3). Consistent with this is our observation that the CEN3-MAT genetic distance is 19 cM in insertless strains but 12 cM in strains with a hemizygous insert. DSBs in a hemizygous insert cannot contribute to recombinants in flanking sequences, since there are no corresponding sequences on the homolog with which to recombine. However, hemizygous inserts might reduce crossing over in flanking sequences if the DSB sites within the URA3-arg4 inserts are able to recruit the few DSB forming factors present in the cold region by a competition mechanism similar to that previously described (16, 67, 71).

Alternatively, recombination in the cold region might result from events that initiate outside the region and later move into it, either by branch migration of a four-stranded junction (23) or by DNA synthesis-driven bubble migration (40). The 40% reduction in crossing over conferred by hemizygous inserts might be due to the resulting nonhomology blocking intermediate movement (52). It is difficult to reconcile this mechanism with the steep boundary seen between hot and cold regions at or near the centromere, and also with the fact that similar reductions are seen for inserts throughout the cold region. We therefore consider it unlikely that events initiated outside the central cold region make a substantial contribution to crossovers that occur within it.

In conclusion, we believe that the most likely explanation for the recombination events that occur in the cold region is that they are initiated by lesions formed inside the cold region, either by DSBs in the native sequences that are not localized enough to be detected, by DSBs that are not formed in rad50S mutants, or by lesions that are not DSBs. The failure to detect breaks in sufficient quantities to account for the recombination seen in the chromosome III central cold region remains a significant challenge to the general applicability of the DSB model as a mechanism to account for all meiotic recombination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. J. Louis, Y. Watanabe, H. Debrauwère, and A. Nicolas for sharing unpublished data, Pfizer Inc. for providing CP-115,953, Y. Pommier for VM26, F. Baudat and A. Nicolas for the YCR098c probe, New England Biolabs for advice on pulsed-field gel sample preparation, and A. S. H. Goldman, M. Mortin, C. Vinson, and R. Shroff for comments that improved the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alani E, Padmore R, Kleckner N. Analysis of wild-type and rad50 mutants of yeast suggests an intimate relationship between meiotic chromosome synapsis and recombination. Cell. 1990;61:419–436. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90524-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker B S, Carpenter A T, Esposito M S, Esposito R E, Sandler L. The genetic control of meiosis. Annu Rev Genet. 1976;10:53–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.10.120176.000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baudat F, Nicolas A. Clustering of meiotic double-strand breaks on yeast chromosome III. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5213–5218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker D M, Guarente L. High-efficiency transformation of yeast by electroporation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:182–187. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bickel S E, Wyman D W, Miyazaki W Y, Moore D P, Orr-Weaver T L. Identification of ORD, a Drosophila protein essential for sister chromatid cohesion. EMBO J. 1996;15:1451–1459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borde V, Duguet M. In vivo topoisomerase II cleavage sites in the ribosomal DNA of Physarum polycephalum. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5787–5795. doi: 10.1021/bi952676q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao L, Alani E, Kleckner N. A pathway for generation and processing of double-strand breaks during meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1990;61:1089–1101. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90072-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chikashige Y, Ding D Q, Imai Y, Yamamoto M, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y. Meiotic nuclear reorganization: switching the position of centromeres and telomeres in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 1997;16:193–202. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson D S, Murray A W, Szostak J W. An alternative pathway for meiotic chromosome segregation in yeast. Science. 1986;234:713–717. doi: 10.1126/science.3535068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Debrauwère, H., and A. Nicolas. 1998. Personal communication.

- 11.de Massy B, Baudat F, Nicolas A. Initiation of recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae haploid meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11929–11933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dernburg A F, McDonald K, Moulder G, Barstead R, Dresser M, Villeneuve A M. Meiotic recombination in C. elegans initiates by a conserved mechanism and is dispensable for homologous chromosome synapsis. Cell. 1998;94:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elsea S H, Osheroff N, Nitiss J L. Cytotoxicity of quinolones toward eukaryotic cells. Identification of topoisomerase II as the primary cellular target for the quinolone CP-115,953 in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13150–13153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan Q, Xu F, Petes T D. Meiosis-specific double-strand DNA breaks at the HIS4 recombination hot spot in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: control in cis and trans. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1679–1688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan Q Q, Petes T D. Relationship between nuclease-hypersensitive sites and meiotic recombination hot spot activity at the HIS4 locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2037–2043. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan Q Q, Xu F, White M A, Petes T D. Competition between adjacent meiotic recombination hotspots in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;145:661–670. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbertson L A, Stahl F W. Initiation of meiotic recombination is independent of interhomologue interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11934–11937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman A S, Lichten M. The efficiency of meiotic recombination between dispersed sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae depends upon their chromosomal location. Genetics. 1996;144:43–55. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottschling D E. Telomere-proximal DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is refractory to methyltransferase activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4062–4065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.4062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goyon C, Lichten M. Timing of molecular events in meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: stable heteroduplex DNA is formed late in meiotic prophase. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:373–382. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross D S, Garrard W T. Nuclease hypersensitive sites in chromatin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:159–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassold T, Merrill M, Adkins K, Freeman S, Sherman S. Recombination and maternal age-dependent nondisjunction: Molecular studies of trisomy 16. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:867–874. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holliday R. A mechanism for gene conversion in fungi. Genet Res. 1964;5:282–304. doi: 10.1017/S0016672308009476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaback D B, Guacci V, Barber D, Mahon J W. Chromosome size-dependent control of meiotic recombination. Science. 1992;256:228–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1566070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kane S M, Roth R. Carbohydrate metabolism during ascospore development in yeast. J Bacteriol. 1974;118:8–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.118.1.8-14.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keeney S, Kleckner N. Communication between homologous chromosomes: genetic alterations at a nuclease-hypersensitive site can alter mitotic chromatin structure at that site both in cis and in trans. Genes Cells. 1996;1:475–489. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klapholz S, Waddell C S, Esposito R E. The role of the SPO11 gene in meiotic recombination in yeast. Genetics. 1985;110:187–216. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleckner N. Meiosis: how could it work? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8167–8174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein S, Zenvirth D, Dror V, Barton A B, Kaback D B, Simchen G. Patterns of meiotic double-strand breakage on native and artificial yeast chromosomes. Chromsoma. 1996;105:276–284. doi: 10.1007/BF02524645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koehler K E, Hawley R S, Sherman S, Hassold T. Recombination and nondisjunction in humans and flies. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1495–1504. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.supplement_1.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamb N E, Feingold E, Savage A, Avramopoulos D, Freeman S, Gu Y, Hallberg A, Hersey J, Karadima G, Pettay D, Saker D, Shen J, Taft L, Mikkelsen M, Petersen M B, Hassold T, Sherman S L. Characterization of susceptible chiasma configurations that increase the risk for maternal nondisjunction of chromosome 21. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1391–1399. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamb N E, Freeman S B, Savage-Austin A, Pettay D, Taft L, Hersey J, Gu Y, Shen J, Saker D, May K M, Avramopoulos D, Petersen M B, Hallberg A, Mikkelsen M, Hassold T J, Sherman S L. Susceptible chiasmate configurations of chromosome 21 predispose to non-disjunction in both maternal meiosis I and meiosis II. Nat Genet. 1996;14:400–405. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambie E J, Roeder G S. Repression of meiotic crossing over by a centromere (CEN3) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1986;114:769–789. doi: 10.1093/genetics/114.3.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambie E J, Roeder G S. A yeast centromere acts in cis to inhibit meiotic gene conversion of adjacent sequences. Cell. 1988;52:863–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lichten M, Borts R H, Haber J E. Meiotic gene conversion and crossing over between dispersed homologous sequences occurs frequently in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1987;115:233–246. doi: 10.1093/genetics/115.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lichten M, Goldman A S. Meiotic recombination hotspots. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:423–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Wu T-C, Lichten M. The location and structure of double-strand DNA breaks induced during yeast meiosis: evidence for a covalently linked DNA-protein intermediate. EMBO J. 1995;14:4599–4608. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu L F. DNA topoisomerase poisons as antitumor drugs. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:351–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Louis E. Whole chromosome analysis. Methods Microbiol. 1998;26:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malkova A, Ivanov E L, Haber J E. Double-strand break repair in the absence of RAD51 in yeast: a possible role for break-induced DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7131–7136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKee A H, Kleckner N. A general method for identifying recessive diploid-specific mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, its application to the isolation of mutants blocked at intermediate stages of meiotic prophase and characterization of a new gene SAE2. Genetics. 1997;146:797–816. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKim K S, Green-Marroquin B L, Sekelsky J J, Chin G, Steinberg C, Khodosh R, Hawley R S. Meiotic synapsis in the absence of recombination. Science. 1998;279:876–878. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKim K S, Hayashi-Hagihara A. mei-W68 in Drosophila melanogaster encodes a Spo11 homolog: evidence that the mechanism for initiating meiotic recombination is conserved. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2932–2942. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore D P, Miyazaki W Y, Tomkiel J E, Orr-Weaver T L. Double or nothing: a Drosophila mutation affecting meiotic chromosome segregation in both females and males. Genetics. 1994;136:953–964. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mortimer R K, Contopoulou C R, King J S. Genetic and physical maps of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, edition 11. Yeast. 1992;8:817–902. doi: 10.1002/yea.320081002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mortimer R K, Schild D. Genetic mapping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Strathern J N, Jones E W, Broach J R, editors. The molecular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces: life cycle and inheritance. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1981. pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicklas R B. How cells get the right chromosomes. Science. 1997;275:632–637. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nicolas A. Relationship between transcription and initiation of meiotic recombination: toward chromatin accessibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:87–89. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohta K, Nicolas A, Furuse M, Nabetani A, Ogawa H, Shibata T. Mutations in the MRE11, RAD50, XRS2, and MRE2 genes alter chromatin configuration at meiotic DNA double-stranded break sites in premeiotic and meiotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:646–651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohta K, Shibata T, Nicolas A. Changes in chromatin structure at recombination initiation sites during yeast meiosis. EMBO J. 1994;13:5754–5763. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06913.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oliver S G, et al. The complete DNA sequence of yeast chromosome III. Nature. 1992;357:38–46. doi: 10.1038/357038a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panyutin I G, Hsieh P. Formation of a single base mismatch impedes spontaneous DNA branch migration. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:413–424. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prinz S, Amon A, Klein F. Isolation of COM1, a new gene required to complete meiotic double-strand break-induced recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;146:781–795. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rattray A J, Symington L S. Stimulation of meiotic recombination in yeast by an ARS element. Genetics. 1993;134:175–188. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reynolds A E, McCarroll R M, Newlon C S, Fangman W L. Time of replication of ARS elements along yeast chromosome III. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4488–4494. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.10.4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roeder G S. Meiotic chromosomes: it takes two to tango. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2600–2621. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roeder G S. Sex and the single cell: meiosis in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10450–10456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ross L O, Rankin S, Shuster M F, Dawson D S. Effects of homology, size and exchange on the meiotic segregation of model chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;142:79–89. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith K N, Nicolas A. Recombination at work for meiosis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:200–211. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trelles-Sticken E, Loidl J, Scherthan H. Bouquet formation in budding yeast: initiation of recombination is not required for meiotic telomere clustering. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:651–658. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Udvardy A, Schedl P. Chromatin structure, not DNA sequence specificity, is the primary determinant of topoisomerase II sites of action in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4973–4984. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uhlmann F, Nasmyth K. Cohesion between sister chromatids must be established during DNA replication. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1095–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wach A. PCR-synthesis of marker cassettes with long flanking homology regions for gene disruptions in S. cerevisiae. Yeast. 1996;12:259–265. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19960315)12:3%3C259::AID-YEA901%3E3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watanabe, Y., and P. Nurse. 1999. Personal communication.

- 66.Weiss K, Simpson R T. High-resolution structural analysis of chromatin at specific loci: Saccharomyces cerevisiae silent mating type locus HMLα. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5392–5403. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu T-C, Lichten M. Factors that affect the location and frequency of meiosis-induced double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1995;140:55–66. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu T-C, Lichten M. Meiosis-induced double-strand break sites determined by yeast chromatin structure. Science. 1994;263:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.8290959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu T-C, Lichten M. Position effects in meiotic recombination. In: Cooper G, Haseltine F, Heyner S, Straus J, editors. Meiosis II: contemporary approaches to the study of meiosis. Washington, D.C: American Academy for the Advancement of Science; 1993. pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu, T.-C., and M. Lichten. Unpublished data.

- 71.Xu L, Kleckner N. Sequence non-specific double-strand breaks and interhomolog interactions prior to double-strand break formation at a meiotic recombination hot spot in yeast. EMBO J. 1995;14:5115–5128. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zenvirth D, Arbel T, Sherman A, Goldway M, Klein S, Simchen G. Multiple sites for double-strand breaks in whole meiotic chromosomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1992;11:3441–3447. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]