Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic continues with emergence of new variants of concerns. These variants are fueling the third and fourth waves of pandemic across many nations. Here we describe the new emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 and why they have enhanced infectivity and possess the ability to evade immunity.

The coronavirus disease that started in 2019, named COVID-19, has induced more than 210 million cases and 4 million deaths in September 2021, following the infection by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2, Sharma et al. 2020, 2021). Actually, many scientific issues remain unanswered such as the virus origin, transmission and adaptation, and the role of environmental factors such as pollution (Chen et al. 2021a, b; Choi et al. 2021a, b; Dai et al. 2021; Khan et al. 2021; Roviello and Roviello 2020; Paital and Agrawal 2021; Sun and Han 2021; Ufnalska and Lichtfouse 2021). Despite the design and massive administration of several vaccines, the pandemic continues with emergence of new variants of concerns, similarly to the Greek mythological phoenix, an immortal bird that cyclically regenerates by obtaining new life by arising from the ashes of its predecessor. These variants are fueling the third and fourth waves of the pandemic across many nations. Here, we describe the new emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 and why they have enhanced infectivity and possess the ability to evade immunity.

Variants of concern

SARS-CoV-2 has slower mutation rate than other RNA viruses due to the presence of the proofreading 3’-5’ exonuclease nsp14 (Robson et al. 2020). However, many viral genome replications that occur during the pandemic are increasing the genetic diversity of SARS-CoV-2. Most mutations are detrimental to virus fitness, yet mutations beneficial to virus survival and transmission are selected and accumulated over time to give rise to variants with enhanced transmissibility, hence leading to a rapid rise of worldwide infections. Variant of concerns are variants for which there is significant evidence to have increased transmissibility, disease severity, and immune evasion potency. Currently, four variants of SARS-CoV-2, alpha—lineage B.1.1.7, beta—lineage B.1.351, gamma—lineage P.1, and delta—lineage B.1.617.2 are recognized as variants of concern by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Table 1). The two main features that control the natural selection of SARS-CoV-2 are the extreme variability of disease severity and the temporal patterns of viral shedding. Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection undergo a range of clinical symptoms, from no symptoms to critical illness and death (Garcia 2020). About one fourth of infections are asymptomatic cases (Alene et al. 2021). Theoretically, direct selection pressure against virulence of SARS-CoV-2 is likely very weak because of the wide symptomatic spectrum and the fact that the peak viral load and transmissibility occur days before symptom onset. However, there is evidence that all four variants of concern have increased disease severity (https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern).

Table 1.

Variants of concern according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, on December 8, 2021

| Nextstrain Clade(b) | WHO Classification | Pango Lineage(a) | Sequence change | Spike Protein Substitutions | First Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20I/501Y.V1 | Alpha | B.1.1.7 |

Δ(21,767 ~ 21,773) Δ(21,991 ~ 21,993) |

69 ~ 70 del 144del | United Kingdom |

| G23012A | (E484K*) | ||||

| T23042C | (S494P*) | ||||

| A23063T | N501Y | ||||

| C23271A | A570D | ||||

| A23403G | D614G | ||||

| C23604A | P681H | ||||

| C23709T | T716I | ||||

| T24506G | S982A | ||||

| G24914C | D1118H | ||||

| G25135C | (K1191N*) | ||||

| 20H/501.V2 | Beta |

B.1.351 B.1.351.2 B.1.351.3 |

A21801C | D80A | South Africa |

| A22206G | D215G | ||||

| Δ(22,283 ~ 22,291) | 241 ~ 3 del | ||||

| G22813C | K417N | ||||

| G23012A | E484K | ||||

| A23063T | N501Y | ||||

| A23403G | D614G | ||||

| C23664T | A701V | ||||

| 20 J/501Y.V3 | Gamma |

P.1 P.1.1 P.1.2 |

C21614T | L18F |

Japan Brazil |

| C21621A | T20N | ||||

| C21638T | P26S | ||||

| G21974T | D138Y | ||||

| G22132C | R190S | ||||

| A22812C | K417T | ||||

| G23012A | E484K | ||||

| A23063T | N501Y | ||||

| A23403G | D614G | ||||

| C23525T | H655Y | ||||

| C24642T | T1027I | ||||

| 21A/S:478 K | Delta |

B.1.617.2 AY.1 AY.2 AY.3 |

C21618G |

T19R (V70F*) T95I |

India |

| G21770T | |||||

| C21846T | |||||

| G21987A | |||||

| Δ(22,028 ~ 22,033) | G142D | ||||

| A22034G | E156- F157- | ||||

| C22227T | R158G | ||||

| G22335T | (A222V*) | ||||

| G22813C | (W258L*) | ||||

| T22917G | (K417N*) | ||||

| C22995A | L452R | ||||

| A23403G | T478K | ||||

| C23604G | D614G | ||||

| G24410A | P681R | ||||

| D950N |

(*) = detected in some sequences but not all

aPhylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak (PANGO) Lineages is a software tool developed by members of the Rambaut Lab. The associated web application was developed by the Centre for Genomic Pathogen Surveillance in South Cambridgeshire and is intended to implement the dynamic nomenclature of SARS-CoV-2 lineages, known as the PANGO nomenclature

bNextstrain, a collaboration between researchers in Seattle, USA and Basel, Switzerland, provides an open-source tool for visualizing the genetics of outbreaks. The goal is to support public health surveillance by facilitating understanding of the spread and evolution of pathogens

Evolving viral keys unlock cell entrance

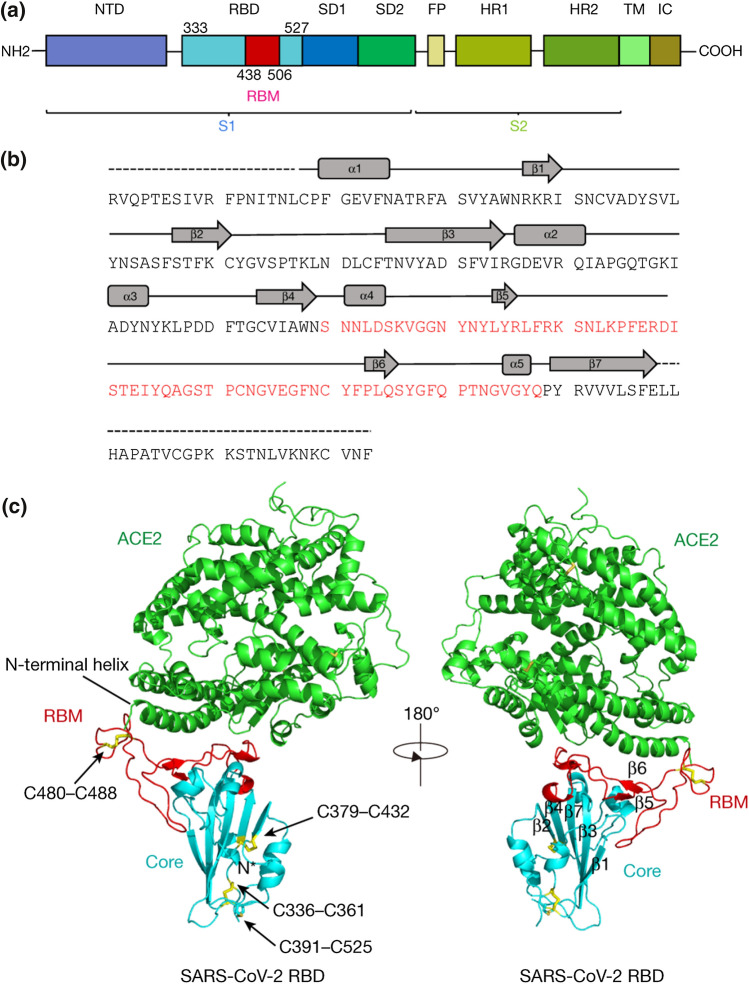

Amid rapid spread of COVID-19, transmissibility is a major selective force for SARS-CoV-2. Indeed, higher viral loads are increasing the transmission rate and, in turn, more transmission can be accompanied by more severe illness. The transmission rate is mainly controlled by the recognition and binding of the virus to host cells. The spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV-2 plays a key role in the receptor recognition and cell membrane fusion process (Hoffmann et al. 2020; Luchini et al. 2021). In the host cell membrane, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) has been identified as the viral receptor (Fig. 1). The S glycoprotein mediates the entry of the virus into host cells through its receptor-binding domain (RBD) and ACE2 interaction (Wan et al. 2020; Yan et al. 2020). The crystal structure of the S glycoprotein bound to ACE2 has been determined (Lan et al. 2020). SARS-CoV-2 has an almost identical binding complex as SARS-CoV-1, the coronavirus strain that caused the death of 9% of patients in 2003, but SARS-CoV-2 displays a tenfold higher binding affinity (Li et al. 2005). Indeed, in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain, hydrogen bonds are formed between amino acid residues of host ACE2 and the following sites of the virus spike protein: K417, G446, Y449, N487, Y489, Q493, T500, N501, G502, and Y505. A salt-bridge connection has also been identified between the virus K417 site and the D30 site of host ACE2 (Lan et al. 2020). Here, mutations in the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein can result in higher affinity to ACE2 and can thus lead to an increase in infectivity and transmissibility of the virus. For instance, N501 is mutated in alpha, beta, and gamma variants. Mutations in K417 are found in beta, gamma, and delta plus variant-lineage AY.1.

Fig. 1.

a Overall topology of the spike monomer of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). b Sequence and secondary structures of SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD). The RBM sequence is shown in red. c Overall structure of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD bound to ACE2. ACE2 is shown in green. The SARS-CoV-2 RBD core is shown in cyan and receptor-binding motif (RBM) in red. Disulfide bonds in the SARS-CoV-2 RBD are shown as sticks and indicated by arrows. The N-terminal helix of ACE2 responsible for binding is labeled. ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; FP: fusion peptide; HR1: heptad repeat 1; HR2: heptad repeat 2; IC: intracellular domain; NTD: N-terminal domain; SD1: subdomain 1; SD2: subdomain 2; TM: transmembrane region.

Adapted from Lan et al. (2020) with permission from Nature

Zoonosis

Human-to-animal and animal-to-human transmission, favored by pollution, are very likely routes for the pandemic origin and propagation, and for vaccine failure (He et al. 2021a,b). Research on interspecies transmission reveals that amino acid residues play major roles in the virus transmissibility. For instance, the Danish Cluster 5 variant has spread from human to minks as a reverse-zoonotic transmission in Denmark then followed by minks to human transmission (Oreshkova et al. 2020; Oude Munnink et al. 2021). This variant contains the Y453F mutation in its receptor-binding domain of the S glycoprotein which is associated with a fourfold higher affinity to ACE2 (Welkers et al. 2021). A mouse adapted SARS-CoV-2 strain carry Q493K, Q498Y and P499T mutations (Leist et al. 2020). Tiger and lion were infected with SARS-CoV-2, which contain F456Y or Y505H mutations in the receptor-binding domain, respectively (McAloose et al. 2020).

Immune evasion

As worldwide vaccination progresses, the immune evasion potency becomes a stronger selective force in viral evolution. Indeed, the antigenic ability of the virus can change as mutations alter the protein structure. Some mutations can lead to reduced effectiveness of the existing vaccines which were developed against the original strain of the virus. For example, the receptor-binding motif (RBM) is a small patch of about 70 amino acids located in the receptor-binding domain of the host ACE2. In this domain, amino acid residues not only form bonds with the virus spike protein, but also serve as antibody binding epitopes for many neutralizing antibodies. Here, the weakening of some neutralizing antibody binding is attributed to mutations of residues K417 and E484 (Chen et al. 2021a, b; Wise 2021). K417N mutations have been found in beta and delta plus variants. Gamma variant contains a K417T mutation. E484K mutation is found in beta and gamma variants. The N-terminal domain (NTD) is another major target for neutralizing antibodies. Two deletion mutations, 69–70 ∆HV and 144 ∆Y, in the N-terminal domain of the spike protein confer the resistance against the NTD-directed antibodies to alpha variants. The resistance against NTD-targeting antibodies of beta variant largely comes from the R246I mutation. The P26S, L18F, T20N, D138Y, and R190S mutations play similar roles in immune evasion of the gamma variant.

There are heightened concerns about the existing COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against current and emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2. Potency of vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants showed several fold reductions against gamma and delta variants, and about 20–40 fold decreases against beta variant (Noori et al. 2021). However, the impact of this neutralization titer reduction on vaccine effectiveness is hard to predict. Although neutralizing antibody levels are predictive of immune protection, the threshold of neutralization for vaccine protection is not known yet (Khoury et al. 2021). Furthermore, the impact of the other potential protective factors besides neutralizing antibody levels, such as T-cell mediated immunity and memory B-cell, has not been fully understood yet.

Delta variant

SARS-CoV-2 is expected to continuously change. Some variants will emerge and replace existing variants. The Delta variant is currently the subject of the main concern. Delta variant contains L452R and T478K in the receptor-binding motif and P681R in the S1/S2 cleavage site in its spike protein. Delta variants are rapidly spread globally and reached actually more than 90% of new cases in US (https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions). The delta variant is highly contagious. The transmission rate is 2 to 3 times higher than original virus, and the viral load in respiratory tract is about 1,000 times higher than original virus (Li et al. 2021). Delta variants show reduced sensitivity to sera from vaccinated individuals (Planas et al., 2021). However, current vaccines are still highly effective against the delta variant (Nasreen et al. 2021; Sheikh et al. 2021). For instance, only modest difference of the vaccine effectiveness between delta and alpha variants was reported when two doses of the BNT162b2 Pfizer–BioNTech or the Oxford–AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccines were received (Lopez Bernal et al. 2021). However, some vaccinated can not only be infected with Delta variants but also may spread virus to others (Brown et al. 2021).

As SARS-CoV-2 spread rapidly, there is a higher chance that new variants can escape immune surveillance, thus rendering current vaccines ineffective. Thorough investigations of variant infection cases and close monitoring of the emergence of new variant are urgently needed. Expediting vaccine deployment and implementing other mitigation measures including mask wearing and social distancing are critical in preventing the emergence and transmission of vaccine escape variants of SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, in the long run, research on alternative cures and prevention measures is definitively needed to outsmart the virus adaptation (Dai et al. 2021).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Virender K. Sharma, Email: vsharma@tamu.edu

Chetan Jinadatha, Email: Chetan.Jinadatha@va.gov.

References

- Alene M, Yismaw L, Assemie MA, Ketema DB, Mengist B, Kassie B, Birhan TY. Magnitude of asymptomatic COVID-19 cases throughout the course of infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0249090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CM, Vostok J, Johnson H, Burns M, Gharpure R, Sami S, Sabo RT, Hall N, Foreman A, Schubert PL, et al. Outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infections, including COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infections, associated with large public gatherings - Barnstable County, Massachusetts, July 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(31):1059–1062. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7031e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RE, Zhang X, Case JB, Winkler ES, Liu Y, VanBlargan LA, Liu J, Errico JM, Xie X, Suryadevara N, et al. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Nat Med. 2021;27(4):717–726. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01294-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Jia P, Han J. Role of indoor aerosols for COVID-19 viral transmission: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:1953–1970. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Chatterjee P, Coppin JD, Martel JA, Hwang M, Jinadatha C, Sharma VK. Current Understanding of the Surface Contamination and Contact Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Healthcare Settings. Environ Chem Lett. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Chatterjee P, Lichtfouse E, Tolefree JA, Hwang M, Jinadatha C, Sharma VK. Classical and alternative disinfection strategies of controlling SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare facilities. Environ Chem Lett. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01180-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Han J, Lichtfouse E. Smarter cures to combat COVID-19 and future pathogens: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:2759–2771. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01224-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia LF. Immune response, inflammation, and the clinical spectrum of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1441. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Han J, Lichtfouse E. Backward transmission of COVID-19 from humans to animals may propagate reinfections and induce vaccine failure. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:763–768. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01140-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Shao W, Han J. Have artificial lighting and noise pollution caused zoonosis and the COVID- 19 pandemic? a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01291-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Kruger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280 e278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AH, Tirth V, Fawzy M, et al. COVID-19 transmission, vulnerability, persistence and nanotherapy: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:2773–2787. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01229-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, Subbarao K, Kent SJ, Triccas JA, Davenport MP. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, Shan S, Zhou H, Fan S, Zhang Q, Shi X, Wang Q, Zhang L, et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581(7807):215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leist SR, Dinnon KH, 3rd, Schafer A, Tse LV, Okuda K, Hou YJ, West A, Edwards CE, Sanders W, Fritch EJ, et al. A mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 induces acute lung injury and mortality in standard laboratory mice. Cell. 2020;183(4):1070–1085 e1012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309(5742):1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Deng A, Li K, Hu Y, Li Z, Xiong Q, Liu Z, Guo Q, Zou L, Zhang H, et al. Viral infection and transmission in a large well-traced outbreak caused by the Delta SARS-CoV-2 variant. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.07.07.21260122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, Thelwall S, Stowe J, Tessier E, Groves N, Dabrera G, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchini A, Micciulla S, Corucci G, Batchu KC, Santamaria A, Laux V, Darwish T, Russell RA, Thepaut M, Bally I, et al. Lipid bilayer degradation induced by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein as revealed by neutron reflectometry. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):14867. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93996-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAloose D, Laverack M, Wang L, Killian ML, Caserta LC, Yuan F, Mitchell PK, Queen K, Mauldin MR, Cronk BD, et al. From people to panthera natural SARS-CoV-2 infection in tigers and lions at the Bronx Zoo. Mbio. 2020 doi: 10.1128/mBio.02220-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreen S, Chung H, He S, Brown KA, Gubbay JB, Buchan SA, Fell DB, Austin PC, Schwartz KL, Sundaram ME, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against variants of concern in Ontario, Canada. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.06.28.21259420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Arshi S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Ansarin K, Kolahi AA, Safiri S. Potency of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome-CoV-2 variants of concern: A systematic review of in vitro studies. Rev Med Virol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/rmv.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oreshkova N, Molenaar RJ, Vreman S, Harders F, Munnink BBO, Hakze-van der Honing RW, Gerhards N, Tolsma P, Bouwstra R, Sikkema RS, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks, the Netherlands. Euro Surveill. 2020 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.23.2001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oude Munnink BB, Sikkema RS, Nieuwenhuijse DF, Molenaar RJ, Munger E, Molenkamp R, van der Spek A, Tolsma P, Rietveld A, Brouwer M, et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on mink farms between humans and mink and back to humans. Science. 2021;371(6525):172–177. doi: 10.1126/science.abe5901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paital B, Agrawal PK. Air pollution by NO2 and PM2.5 explains COVID-19 infection severity by overexpression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in respiratory cells: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:25–42. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01091-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas D, Veyer D, Baidaliuk A, Staropoli I, Guivel-Benhassine F, Rajah MM, Planchais C, Porrot F, Robillard N, Puech J, et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596(7871):276–280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson F, Khan KS, Le TK, Paris C, Demirbag S, Barfuss P, Rocchi P, Ng WL. Coronavirus RNA proofreading: molecular basis and therapeutic targeting. Mol Cell. 2020;79(5):710–727. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roviello V, Roviello GN. Lower COVID-19 mortality in Italian forested areas suggests immunoprotection by Mediterranean plants. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:699–710. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01063-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma VK, Jinadatha C, Lichtfouse E. Environmental chemistry is most relevant to study coronavirus pandemics. Environ Chem Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma VK, Jinadatha C, Lichtfouse E, et al. COVID-19 epidemiologic surveillance using wastewater. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:1911–1915. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01188-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh A, McMenamin J, Taylor B, Robertson C. SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness. Lancet. 2021;397(10293):2461–2462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01358-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Han J. Open defecation and squat toilets, an overlooked risk of fecal transmission of COVID-19 and other pathogens in developing communities. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01143-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ufnalska S, Lichtfouse E. Unanswered issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ Chem Lett. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01249-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welkers MRA, Han AX, Reusken C, Eggink D. Possible host-adaptation of SARS-CoV-2 due to improved ACE2 receptor binding in mink. Virus Evol. 2021;7(1):veaa094. doi: 10.1093/ve/veaa094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise J. Covid-19: The E484K mutation and the risks it poses. BMJ. 2021;372:n359. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]