Abstract

Objective:

To better characterize the ways that migraine affects multiple domains of life.

Background:

Further understanding of migraine burden is needed.

Methods:

Adults with migraine randomized to mindfulness-based stress reduction or headache education arms (n = 81) in two separate randomized clinical trials participated in semistructured in-person qualitative interviews conducted after the interventions. Interviews queried participants on migraine impact on life and were audio-recorded, transcribed, and summarized into a framework matrix. A master codebook was created until meaning saturation was reached and magnitude coding established code frequency. Themes and subthemes were identified using a constructivist grounded theory approach.

Results:

Despite most participants being treated with acute and/or prophylactic medications, 90% (73/81) reported migraine had a negative impact on overall life, with 68% (55/81) endorsing specific domains of life impacted and 52% (42/81) describing impact on emotional health. Six main themes of migraine impact emerged: (1) global negative impact on overall life; (2) impact on emotional health; (3) impact on cognitive function; (4) impact on specific domains of life (work/career, family, social); (5) fear and avoidance (pain catastrophizing and anticipatory anxiety); and (6) internalized and externalized stigma. Participants reported how migraine (a) controls life, (b) makes life difficult, and (c) causes disability during attacks, with participants (d) experiencing a lack of control and/or (e) attempting to push through despite migraine. Emotional health was affected through (a) isolation, (b) anxiety, (c) frustration/anger, (d) guilt, (e) mood changes/irritability, and (f) depression/hopelessness. Cognitive function was affected through concentration and communication difficulties.

Conclusions:

Migraine has a global negative impact on overall life, cognitive and emotional health, work, family, and social life. Migraine contributes to isolation, frustration, guilt, fear, avoidance behavior, and stigma. A greater understanding of the deep burden of this chronic neurological disease is needed to effectively target and treat what is most important to those living with migraine.

Keywords: chronic illness, coping, disease burden, headache, patient-centered, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Migraine is the second leading cause of disability worldwide with a substantial impact on quality of life, expanding from interpersonal relationship dynamics to occupational functioning and overall well-being.1–7 Although research has begun exploring the impact of migraine on family life, education, career, and finances,4,8–12 there is more to learn to better characterize the full range of domains of life impacted by this chronic neurological disease.2,8,10,11 Compared with many chronic pain conditions that increase in prevalence with age,13 migraine is most prevalent during the peak years of life productivity (25–55 years),14–16 which directly contributes to differential impact in different domains of quality of life. Understanding the disease impact of migraine is important to (1) inform patient-reported outcomes for migraine studies and trials; (2) characterize the true burden of disease in hopes to increase resource allocation to treating and mitigating the full effect of migraine; and (3) create treatment regimens that address all impacts of migraine to enhance disease management.2,8,9

Depression and anxiety are highly comorbid with migraine,6,15,17 although the effects of migraine on well-being may be broader than previously conceptualized, including other realms such as guilt, anger, and attenuated physical and cognitive functioning.3,6,8–10 Recognizing the ways in which migraine impacts emotional functioning can provide additional treatment targets in people with migraine beyond primary psychiatric dysfunction.

The objective of the current study was to better characterize the ways that migraine affects multiple domains of life in adults with migraine. Qualitative interviews were conducted with patients who participated in trials of nondrug interventions for migraine to assess their experiences with the study. We also specifically queried about the impact of migraine on their lives. These participants can be expected to be willing to introspect on the various aspects of quality of life impacted by migraine as they were treatment-seeking, suggesting they experienced disease burden they attributed to migraine. Through the voices of patients living with migraine, we hoped to gain rich insights and perspectives on the domains of life impacted by migraine.

METHODS

Semistructured qualitative interviews (n = 81) based on grounded theory18 were conducted as part of two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in adults with migraine (full study details reported elsewhere).19,20 MBSR teaches participants mindfulness through didactic and experiential learning during eight weekly 2-hour classes. The pilot RCT, conducted in Boston, MA, enrolled participants with 4–14 migraine days/month between January and March 2012. The larger RCT, conducted in Winston-Salem, NC, enrolled participants with 4–20 migraine days/month between August 2016 and October 2018, with stratification by migraine frequency (low [4–9] vs. high [10–20] days/month with migraine). Participants were not informed of mindfulness course content for the larger study, as recruitment materials described the study as evaluating a “nondrug treatment” with participants masked to treatment assignment. The Headache (HA) Education intervention served as a comparator group that matched the time commitment/attention of the MBSR intervention but provided participants with information on migraine instead of MBSR. Adults with migraine randomized to the MBSR intervention arm of the pilot study (n = 10),19 and the MBSR or HA Education arms of the larger study (MBSR, n = 33; HA Education, n = 38)20 participated in qualitative in-person interviews after completion of the intervention. For study inclusion of both studies: (a) United Council for Neurologic Subspecialties-certified headache physicians conducted in-person evaluations to confirm International Classification of Headache Disorders migraine diagnoses and (b) prospective diaries captured frequency. Participants were able to stay on their current acute and prophylactic migraine medications during both clinical trials and committed to maintaining medication stability for study duration. Both the pilot RCT and the larger RCT were IRB approved (through Partners and Wake Forest Baptist, respectively) and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01545466 and NCT02695498). All participants provided written informed consent.

All interviews used a semistructured interview guide based on grounded theory. All interviewers were trained in qualitative interview techniques, with multiple probing techniques taught to clarify details effectively, without inappropriately leading or directing of participants. Most questions were open-ended. The main areas of focus for the interview guides for both RCTs included the following: (1) medical condition/impact on life; (2) research study experiences; (3) positive and negative aspects of the study; (4) impact of study on migraine; (5) class content/logistics; (6) specific questions about classes; (7) change from the study; (8) study staff; and (9) expectations/beliefs. For the larger RCT, additional areas of focus were added to include questions about (1) heat pain training; (2) questionnaires; (3) headache logs; and (4) estimated headache frequency change for life value. Interviews opened with the question, “How does migraine impact your life?” Additional questions queried on how the interventions affected their experience with migraine. The main intent of the interviews was to capture participants’ experiences during the clinical trials and with the interventions (and these results will be reported elsewhere), so specific domains of life impacted by migraine were not specifically asked. For example, participants were not asked how migraine affected cognitive or emotional health but were asked if they felt the intervention impacted mental, physical, or cognitive health. All interviews were conducted, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim by a blinded team member. The interviews from the larger study lasted on average 47 min (SD 13.9) with a range of 18–77 min and a total of nearly 3300 min of recorded interviews.

Undergraduate, masters, and MD/PhD students (n = 7) worked with the Principal Investigator to analyze the transcripts through weekly team meetings (August 2019–January 2021). A qualitative interview expert (from Wake Forest Qualitative and Patient-Reported Outcomes Developing Shared Resource) provided educational training, consultation, and participation in team meetings for the first 6 months of analysis. All students were educated on qualitative interview techniques and provided educational materials, including the textbook The Coding Manual for Qualitative Research,21 with regularly assigned readings reviewed.

Transcripts were first summarized into a framework matrix using a standardized template with 12 key domains based on the interview guide.22–25 Investigator triangulation26 was achieved through two undergraduate students independently summarizing each transcript, comparing summaries, resolving any discrepancies, and then developing a final summary. After 50% of the summaries were completed in pairs and a consistent summary technique was established, the undergraduate researchers then independently summarized the remaining transcripts. A doctoral candidate on the research team cross-checked all final summaries against the original transcripts to ensure accuracy and completeness. Once all transcripts were summarized, the data were aggregated into a final matrix organized by key domain and cohort. In addition to conversing about challenges and addressing any issues, the weekly team meetings included discussions on emergent ideas and potential codes.

After all team members were familiar with the data through the rapid matrix summary technique, a master codebook was created until meaning saturation was achieved.27 The transcribed interviews were uploaded to Dedoose software, and the codebook was applied to interviews by six coders. Two independent raters assessed at least one third of the interviews, and tests for interrater reliability across team members confirmed consistency. The weekly team meetings continued to provide an opportunity for discussions, with emerging patterns, categories, and themes considered. A constructivist grounded theory approach28 was used to identify themes and subthemes. An iterative process ensued over several months with coding, categorizations, discussions, and resolution of disagreements until team members agreed on final themes and subthemes.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics (e.g., mean and standard deviation) were used to describe continuous data; frequency and percentages were used to describe categorical data. For headache frequency data, median, 25th, and 75th percentiles were also provided. Magnitude coding was applied to establish code frequency21 (codes were counted only once per participant), and Dedoose analysis was used to divide the frequency of code as a function of group (MBSR vs. HA education) to assess whether program effects diverged between groups. A Fisher’s exact test was used to compare MBSR versus HA education groups for each theme/subtheme, with statistical significance defined at p < 0.05. Given the exploratory nature of this research, we defined marginally significant results as p < 0.15, the purpose of which was to highlight possible directional associations that warrant further research. All tests were two-tailed. A thorough audit trail was maintained throughout data analysis to enhance reliability. All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software.29

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of participants were similar in both studies (Table 1). Participants were on average 46 years old (SD 17) in the pilot study and 45 years old (SD 13) in the larger study. Participants were predominantly women, white, privately insured, and had completed college or higher education. The average baseline headache frequency during the 28-day run-in period was 10.4 (SD 3.1) in the pilot study and 9.8 (SD 3.6) in the larger study, with median frequencies of 10 (25th percentile, 75th percentile: 8, 12) and 9 (7, 12), respectively. Participants had a personal history of migraine for 26 years on average (SD ranged from 13 to 19, depending on group), and most also had a headache family history. Headache-related disability was high in both studies, with scores reflective of moderate (MIDAS—1 month)20,30–32 or severe headache-related disability (HIT-6).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants from both clinical trials

| Baseline characteristic | Pilot RCT | Larger RCT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBSR (n = 10) n (%) | MBSR (n = 37)a n (%) | HA Education (n = 38) n (%) | |

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (years); mean (SD) | 46 (17) | 44 (12) | 46 (14) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 9 (90) | 34 (92) | 34 (90) |

| Male | 1 (10) | 3 (8) | 4 (10) |

| Race | |||

| White | 9 (90) | 33 (89) | 33 (87) |

| Black or African-American | 1 (10) | 4 (11) | 5 (13) |

| Primary health insurance | |||

| Private | 8 (80) | 33 (89) | 30 (79) |

| Medicare/medicaid/other public | 2 (20) | 4 (11) | 7 (18) |

| None | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/living with partner | 9 (90) | 27 (74) | 24 (63) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 0 | 5 (13) | 7 (18) |

| Single-never married | 1 (10) | 5 (13) | 7 (18) |

| Current employment statusc | |||

| Employed/self-employed full time (>30 h/week) | 4 (40) | 25 (68) | 22 (58) |

| Employed part-time | 1 (10) | 3 (8) | 4 (11) |

| Student, homemaker, volunteer | 2 (20) | 6 (16) | 2 (5) |

| Unemployed, retired | 3 (30) | 3 (8) | 10 (26) |

| Education | |||

| ≤High school, n (%) | 1 (10) | 3 (8) | 2 (5) |

| College, n (%) | 4 (40) | 20 (54) | 25 (66) |

| Graduate degree, n (%) | 5 (50) | 14 (38) | 11 (29) |

| Recruitment source | |||

| Academic medical center/provider referral | 8 (80) | 18 (49) | 21 (55) |

| Community | 2 (20) | 19 (51) | 17 (45) |

| Headache features | |||

| Disease characteristics during baseline HA log | |||

| Headache days during 28-day baseline, mean (SD) | 10.4 (3.1) | 9.6 (3.4) | 9.9 (3.7) |

| Migraine days during 28-day baseline, mean (SD) | 4.2 (2.9) | 7.3 (2.6) | 7.6 (3.0) |

| Disease history | |||

| Years with migraine, mean (SD)b | 26 (19) | 26 (13) | 26 (14) |

| Migraine with aura | 4 (40) | 14 (38) | 16 (42) |

| Family history of headache | 7 (70) | 25 (68) | 23 (61) |

| Use of treatments | |||

| Current use of prophylactic treatmentc | 8 (80) | 12 (32) | 20 (53) |

| Current use of acute medicationd | 10 (100) | 33 (89) | 31 (82) |

| Experienced headache medication side effect | 5 (50) | 23 (62) | 27 (71) |

| Stress or let-down stress as a trigger | 8 (80) | 28 (76) | 27 (71) |

| Current or past diagnosis of depression | 2 (20) | 15 (41) | 17 (45) |

| Current or past diagnosis of anxiety | 2 (20) | 12 (32) | 17 (45) |

| MIDAS-one month at baseline,e mean (SD) | 12.5 (9.8) | 13.7 (11.5) | 10.0 (6.7) |

| HIT–6 at baseline, mean (SD) | 63.0 (8.0) | 63.0 (7.0) | 62.8 (4.2) |

Note: Instrument score ranges: Migraine Disability Assessment—1 month (0–115), higher scores reflect greater disability, MIDAS is typically used as an average over 3 months; to facilitate interpretation of the MIDAS 1 month data presented, the mean estimate results (but not the confidence intervals) can be multiplied by 3 for conversion to the typical 3-month assessment30; score range for 3-month MIDAS: 0–5 little or no disability, 6–10 mild disability, 11–20 moderate disability, 21+ severe disability.

Headache Impact Test-6 (36–78), higher scores reflect greater headache impact, score range: <49 little to no impact, 50–55 some/moderate impact, 56–59 substantial impact, 60+ severe impact.

Baseline characteristics from the larger RCT represent 75 participants who completed visit 2 (four additional participants than the 71 who participated in the qualitative interviews).

n = 1 missing data (HA Education group).

Use of prophylactic medication from the larger RCT: There was a statistically significant baseline difference between MBSR and HA Education in baseline use of prophylactic medication (p = 0.01).

Missing data from larger RCT for acute medication use n = 9 (n = 3 MBSR group; n = 6 HA Education group).

MIDAS 1 month was used to decrease recall bias and improve the accuracy of the results (compared with the typical 3-month recall period).30–32 MIDAS 1 month results from the larger RCT: there was a statistically significant baseline difference between MBSR and HA Education in baseline measure of MIDAS (p = 0.033). There were three identified outlier patients in the MBSR group with baseline MIDAS scores >50 (for reference, the maximum baseline MIDAS in the Headache Education group was 36). With these outliers removed, the baseline difference between treatment groups is no longer statistically significant (p = 0.201).

Six main themes on the impact of migraine emerged (Table 2): (1) global negative impact on overall life; (2) migraine impact on emotional health; (3) migraine impact on cognitive function; (4) migraine impact on specific domains of life with resulting reactions; (5) fear and avoidance; and (6) stigma surrounding migraine.

TABLE 2.

Summary of themes and subthemes representing impact of migrainea

| Theme 1: Global negative impact on overall life, n = 73 (90%) |

|---|

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 2: Migraine impact on emotional health, n = 42 (52%) |

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 3: Migraine impact on cognitive function, n = 11 (14%) |

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 4: Migraine impact on specific domains of life with resulting reactions, n = 55 (68%) |

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 5: Fear and avoidance, n = 14 (17%) |

| Subthemes |

|

| Theme 6: Stigma surrounding migraine, n = 10 (12%) |

| Subthemes |

|

n = 81; N (%) represented throughout.

Despite most participants being treated with acute and/or prophylactic medications (Table 1), most (90%) of the participants reported migraine had a negative impact on their overall life (theme 1, Table 2) with specific domains of life affected in 68% (theme 4, Table 2). Although self-reported current or prior history of either depression or anxiety ranged from 20% to 45% at baseline in the trials (Table 1), more than half of the participants endorsed migraine having an impact on emotional health (Table 2). Although not specifically queried, 17% of the participants described migraine leading to fear and avoidance behavior, 14% endorsed migraine’s impact on cognitive function, and 12% reported stigma related to migraine (Table 2).

Participants described the global negative impact on overall life (Table 3) by expressing how migraine: (a) controls life; (b) makes life difficult; and (c) causes disability during attacks, with participants (d) experiencing a lack of control over migraine attacks and/or (e) attempting to push through despite migraine. Emotional health was affected through (a) isolation; (b) anxiety; (c) frustration/anger; (d) guilt; (e) mood changes/irritability; and (f) depression/hopelessness (Table 3). Cognitive function was affected through both concentration and communication difficulties (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Global negative impact of migraine on life, cognitive function, and emotional health

| Theme 1: Global negative impact of migraine on life | |

|---|---|

| Subtheme | Representative quotations |

| Migraine controls life |

|

| Migraine makes life difficult |

|

| Migraine causes disability during attacks |

|

| Lack of control over migraine attacks |

|

| Attempting to push through despite the migraine |

|

| Theme 2: Migraine impact on emotional healtha | |

| Subtheme | Representative quotations |

| Isolation |

|

| Anxiety |

|

| Frustration/anger | Uncertainty over “cause” leads to frustration

|

| Guilt |

|

| Mood changes/irritability |

|

| Depression and/or hopelessness |

|

| Theme 3: Migraine impact on cognitive functiona | |

| Concentration difficulties |

|

| Communication challenges |

|

Migraine impacted multiple domains of life (Table 4) including the following: (a) work/career; (b) family life; and (c) social life. Resulting reactions to each domain of life included the following: (a) work/career: guilt, change of job status, presenteeism, financial impact, and school impact; (b) family: frustration, guilt, disrupted time; and (c) social: irritability, altered plans, and communication. Fear and avoidance showed up (Table 5) through (a) pain catastrophizing; (b) anticipatory anxiety; and (c) avoidance behavior due to fear of migraine or fear of migraine trigger. Both externalized and internalized stigma were also reported (Table 5). Representative quotations illustrate the depth of the impact for all themes in Tables 3–5.

TABLE 4.

Migraine impact on multiple specific domains of life

| Theme 4: Migraine impact on specific domains of life with resulting reactions | |

|---|---|

| Subtheme | Reaction to migraine and representative quotations |

| Impact of migraine on work/career | Guilt

|

| Impact of migraine on family life | Frustration

|

| Impact of migraine on social life | Irritability

|

TABLE 5.

Fear, avoidance, and stigma surrounding migraine

| Theme 5: Fear and avoidance | |

|---|---|

| Subtheme | Representative quotations |

| Pain catastrophizing worsens migraine and induces fear |

|

| Anticipatory anxiety induces fear |

|

| Avoidance behavior due to fear of migraine or fear of migraine trigger |

|

| Theme 6: Stigma surrounding migraine | |

| Subtheme | Representative quotations |

| Externalized stigma: participants feel judged | Lack of knowledge in the community

|

| Internalized stigma: participants feel different than others |

|

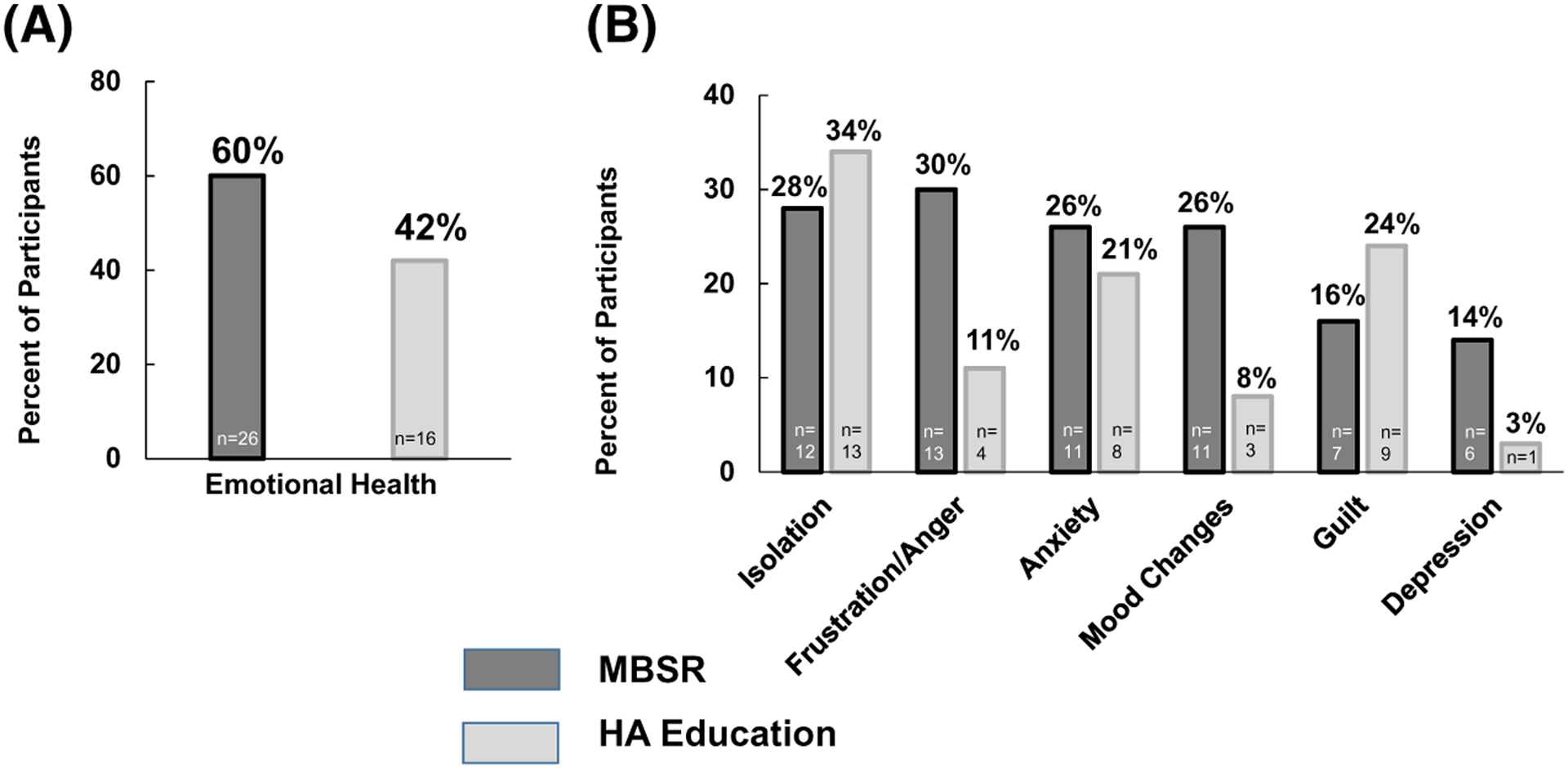

Overall, themes and subthemes were similarly represented across both MBSR and HA Education groups, although a few marginally significant differences across groups were seen (Figures 1 and 2). The global negative impact on overall life was similarly high for both groups: 88% for the MBSR group (n = 38) and 92% for Headache Education (n = 35), p = 0.716 (Figure 1). Impact of migraine on overall domains of life showed similar impact across MBSR (65%, n = 28) and HA Education (71%, n = 27), p = 0.638. Impact of migraine across specific domains of life showed a marginally significant difference across Work (MBSR 37%, n = 16 vs. HA Education 55%, n = 21, p = 0.122) without differences across Family (MBSR 40%, n = 17 vs. HA Education 32%, n = 12, p = 0.494) or Social (MBSR 33% n = 14 vs. HA Education 32%, n = 12, p > 0.999) (Figure 1). Impact of migraine on emotional health showed marginally significant difference across MBSR (60%, n = 26) vs. HA Education (42%, n = 16), p = 0.122 (Figure 2). Within the emotional health subthemes, impact of migraine across frustration/anger showed a marginally significant difference (MBSR 30%, n = 13 vs. HA Education 11%, n = 4, p = 0.054) and also across depression (MBSR 14%, n = 6 vs. HA Education 3%, n = 1, p = 0.114) (Figure 2). Statistically significant differences existed across mood changes (MBSR 26%, n = 11 vs. HA Education 8%, n = 3; p = 0.043) (Figure 2). Impact was similar across groups for isolation (MBSR 28%, n = 12, vs. HA Education 34%, n = 13, p = 0.632), anxiety/worry (MBSR 26%, n = 11 vs. HA Education 21%, n = 8, p = 0.794), and guilt (MBSR 16%, n = 7 vs. HA education 24%, n = 9, p = 0.419) (Figure 2). Migraine’s impact on cognitive function was similar across groups for both concentration difficulties (p = 0.293) and communication difficulties (p = 0.661). Fear/avoidance and stigma were also similar across groups (p = 0.777 and 0.177, respectively).

FIGURE 1.

Global negative impact of migraine (1A), impact of migraine on domains of life (1B), and impact on specific domains of life (1C) across MBSR and HA Education Intervention Arms. (A) The global negative impact on overall life was similarly high for both groups: 88% for the MBSR group (n = 38/43) and 92% for Headache Education (n = 35/38), p = 0.716. (B) Impact of migraine on domains of life showed similar impact across MBSR (65%, n = 28/43) and HA Education (71%, n = 27/38), p = 0.638. (C) Impact of migraine across specific domains of life shows a potential difference across work (MBSR 37%, n = 16/43 vs. HA Education 55%, n = 21/38, p = 0.122) without differences across Family (MBSR 40%, n = 17/43 vs. HA Education 32%, n = 12/38, p = 0.494) or Social (MBSR 33% n = 14/43 vs. HA Education 32%, n = 12/38, p > 0.999)

FIGURE 2.

Impact of migraine on emotional health across mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and headache (HA) Education intervention arms. (A) Impact of migraine on emotional health showed a potential difference across MBSR (60%, n = 26/43) vs. HA Education (42%, n = 16/38), p = 0.122. (B) Impact of migraine across different subthemes of emotional health showed no group differences across isolation (MBSR 28%, n = 12/43, vs. HA Education 34%, n = 13/38, p = 0.632), a potential difference across frustration/anger (MBSR 30%, n = 13/43 vs. HA Education 11%, n = 4/38, p = 0.054), and without differences across anxiety (MBSR 26%, n = 11/43 vs. HA Education 21%, n = 8/38, p = 0.794). Statistically significant differences existed across mood (MBSR 26%, n = 11/43 vs. HA Education 8%, n = 3/38; p = 0.043). No differences were seen across guilt (MBSR 16%, n = 7/43 vs. HA education 24%, n = 9/38, p = 0.419); potential differences existed across depression (MBSR 14%, n = 6/43 vs. HA Education 3%, n = 1/38, p = 0.114)

DISCUSSION

Despite being treated with acute and/or prophylactic medications, most participants in this study reported migraine had a negative impact on overall life and emotional health. Specific domains of life were impacted, including ictal and interictal cognitive functioning and well-being. Impact on career was found to be multifaceted, with roles, responsibilities, and relationships in addition to employment status being impacted by migraine, in addition to family and social dynamics. Furthermore, the impact on emotional health extended beyond the well-described comorbidities of depression and/or anxiety with migraine.15,17 For example, reports of isolation, anger, frustration, and guilt were more prominent in interviews than was formal depression. Participants frequently endorsed anticipatory anxiety, fear of next migraine attack, and internal and external stigma. Altogether, these results extend the work from other studies demonstrating that migraine has a much wider impact on disease burden than what is commonly measured on validated assessments used to collect patient-reported outcomes.1–3,5–10,25,33,34

Guilt was an overarching theme that emerged from these data. Participants reporting feeling guilty about both time away from work, family, and social engagements and the additional burden on friends, family, and colleagues due to inability to fulfill and excel in their responsibilities. One patient reported, “I’d put a lot of blame on myself and get frustrated that I had a migraine and angry at myself that I couldn’t get rid of it. [I blame myself] because I have a rotten brain. Why do I have a defective brain? I just blame myself. It’s my brain so it’s my fault” (Table 5). Guilt’s role in migraine has been recognized recently. For example, data from 13,064 participants in the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study showed the significant family burden of migraine, with guilt playing a role.9 A recent qualitative study evaluating the impact of migraine in women (n = 10) found similar themes and subthemes as our findings.35 Specifically, their themes (and subthemes) included the following: (a) being besieged by an attack (subthemes: being temporarily incapacitated; feeling involuntarily isolated from life); (b) struggling in life characterized by uncertainty (subthemes: being in a state of constant readiness; worrying about the use of medication); and (c) living with an invisible disorder (subthemes: living with the fear of not being believed; struggling to avoid being doubted). Their findings highlighting guilt, isolation, and external and internal stigma of living with migraine further validate these themes from our data. Assessments and qualitative studies need to investigate further the roles of guilt, stigma, and isolation in migraine.

Many participants lamented how the unpredictability of attacks is a major contributor to migraine’s impact on quality of life, creating a pattern of unwelcome unreliability. For this reason, the fear-avoidance model may have more utility in migraine than in other chronic pain conditions whose symptom courses are more predictable or even constant.36 In fact, results from the current study found that the impact of migraine had features similar to panic disorder, such as anticipatory anxiety. Although panic attacks themselves are uncomfortable, the disease takes on a much more profound impact on quality of life when anticipatory anxiety, or the fear of future attacks and subsequent avoidance of situations thought to trigger attacks, becomes a prominent symptom. Similarly, the migraine attack is only one contributor to the impact on quality of life with interictal anticipatory anxiety and concomitant life restriction having critical contributions to quality of life impact. In this study, participants described altering their lives in anticipation of a migraine attack in ways that impacted multiple areas of quality of life. Avoidance behaviors were described as taking people away from valued life activities and social activities. In turn, participants described these life restrictions as impacting their emotional health including increasing the initial anticipatory anxiety and catastrophizing. Both fear of the next migraine attack and fear of triggers were described.

Patients reported a wide-ranging impact of migraine on their social relationships. Migraine was described as affecting relationships with friends, family members, and colleagues at work. Improvements in migraine symptoms may positively influence a wide web of relationships. Improving knowledge and awareness of migraine in the general public could be used to better prepare friends, family, and coworkers to support the migraine management efforts of people with migraine.37 This could reduce the guilt, stigma, and isolation surrounding migraine.34,38 Even in this study, many participants in the HA Education arm described wanting their family and friends to have an educational class to “better understand” migraine and be able to better empathize, as stigmatizing attitudes may be greatest in those who are closest to people with migraine.39 Given the high prevalence of migraine, broad public health migraine educational initiatives and advocacy efforts may help target these factors.38,40–42

Our study underscores the impact of migraine on cognitive function, with participants describing cognitive interference and difficulty with both concentration and communication. One participant reported that during a migraine attack she ends up “sounding like a blooming idiot.” Decreases in cognitive function negatively affect work life, both in the inability to effectively communicate with colleagues and reduced productivity resulting in “presenteeism” (being physically present but unproductive). Difficulty communicating also affects social relationships. Furthermore, participants reported mood changes and irritability with attacks. Although being in pain may contribute to cognitive and mood changes, the pathophysiology of migraine may also play a role. The cognitive and mood effects of migraine and resulting disease burden need additional attention to elucidate the mechanisms behind these changes.

Together, these results highlight the importance of developing standardized, validated measures to capture a fuller picture of the impact of migraine on patients’ lives. Pain-related anxiety significantly impacts disability,43 and many of the questionnaires assessing such impact (e.g., Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale and Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire) were developed to assess patients with chronic pain, but many items are not appropriate for those with migraine. Additional measures, such as the recently developed Impact of Migraine on Partners and Adolescent Children, IMPAC scale,8 are needed to fully identify and track the full scope of the impact of migraine. Measures assessing the impact of migraine on quality of life should emphasize the effects on family, social, occupational, and emotional well-being noted in this study. Further understanding of the impact of stigma on the lived experience of migraine is also critical to ensure that patients do not feel judged for their migraine-induced debilitations or lessen their self-worth due to their disease.34,37 As reflected by recent expert international consensus44 and systematic reviews,45,46 clinical trials should always include outcomes that reflect the full impact of migraine on patient lives through assessing both disability and quality of life. Both disability and quality of life are worthy of being a primary outcome, including for pharmacological treatments as well as for implementation science and nonpharmacological treatment approaches.20,44,47

Beyond improving clinical research, studies such as this one can improve clinical management through tailoring individual treatment approaches to address the burden of migraine on each patient’s life. Recognizing, addressing, and teaching individuals how to manage fear of attacks, stigma, guilt, and frustration are important to optimize migraine management.34,44 Given the emotional impact of migraine combined with the isolation inherent in a chronic neurological disease with debilitating attacks of severe pain and sensory hypersensitivities, providing patients with the opportunity to connect with others similarly affected may have a profound therapeutic effect and help target stigma and isolation.34,42 Given the current social distancing measures of the COVID-19 pandemic, online support groups48 and advocacy organizations connecting migraine patients with each other may be especially powerful.

The key question in the interview guide that helped elucidate these results was, “How does migraine impact your life?” This simple, open-ended question has been demonstrated to provide patients with the opportunity to convey their full experiences with migraine, yielding detailed responses and personal narratives that provide a more compelling understanding of disease burden and disability.49,50 Providers often underestimate their patient’s impairment due to migraine.50,51 Providers who receive information on headache-related impairment from patients are more likely to prescribe migraine-specific medications and have more aggressive follow-up.49–51 A strong predictor of good headache outcome at 1 year is patients’ belief that they have discussed their headache fully with an informed physician at the first visit.52 Open-ended questions do not require significantly more time with patients49,50,53 but are linked to higher levels of both patient and provider satisfaction and may increase the chance of providers offering effective treatment approaches49,50 A simple educational program to teach providers the importance and techniques of open-ended questions can improve alignment between headache patients’ experiences and providers’ understanding, overall improving both patient and provider satisfaction.49,50

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This study has several important strengths, including having a large sample size of 81 qualitative interviews of patients with migraine diagnosed by United Council for Neurologic Subspecialties-certified headache specialists using International Classification of Headache Disorders diagnostic criteria. A similar interview guide was used for both clinical trials conducted in two separate cities, capturing patients with migraine across time and location. Rigorous qualitative methodology was used that appropriately captured, organized, and analyzed the data. The responses are provided in the patients’ voices, which offers a clear articulation of the full impact of migraine in ways that can be used to develop improved assessments for patient-reported outcomes. Although the original intent of the qualitative interviews was to learn how participants responded to the interventions being studied in the context of MBSR clinical trials, asking patients how migraine affects their lives resulted in rich descriptions of disease burden. The use of open-ended questions and lack of directed questions provided a unique window into patient perspectives, highlighting what mattered most to them. The resulting quantitative data demonstrating the frequency of codes that fit within a given theme in response to such open-ended questions give a unique insight into the factors that evoke the greatest burden. Such spontaneous reporting may have captured areas of greatest concern for the patient.

Limitations of the study included that we did not undertake questions directed to specific domains because it was not the original intent of the interviews to capture migraine’s impact on life. For example, had we asked about cognitive impairment during attacks, we may have found that it occurs with greater frequency than identified herein by spontaneous report. Moreover, specifically querying an area could lead to overreporting related to acquiescent responding.54 Baseline characteristics of participants in both studies were predominantly white educated women, thus a nondiverse patient population. Participants in the two trials had either 4–14 or 4–20 migraine days/month and were treatment-seeking; therefore, the results reflect patients with this disease burden. Selection bias may have played a role in the themes that emerged as these participants were willing to participate in a nonpharmacological study, which may decrease generalizability. For example, most participants were refractory to typical drug treatment approaches, possibly leading them to be disillusioned by their experiences living with migraine. However, it is known that response to medication therapy for migraine is variable and often incomplete from a patient’s perspective.55–57

Because the interviews were conducted after the interventions (MBSR or HA Education), the interventions themselves may have played a role in participants’ perceptions or awareness of their migraine experiences. We hypothesized that learning mindfulness may have increased awareness on the impact of migraine on participants’ lives. Moreover, many of the topics of discussion in the HA Education curriculum included migraine’s impact on various aspects of life to suggest that participants in the HA Education group may have given this more thoughtful reflection during the intervention. However, our magnitude coding demonstrated that most themes were similarly represented across both interventions. Of note, the emotional health codes were represented more commonly in those who had participated in MBSR compared with HA Education. This is particularly interesting given that our quantitative RCT results demonstrated that MBSR improved multiple measures of well-being more than HA Education (depression scores, quality of life, headache-related disability, self-efficacy, pain catastrophizing).20 However, mindfulness teaches individuals to pay attention to the present moment in a way that may increase their awareness of how migraine impacts quality of life, while minimizing the associated emotional reactivity. Participants may also have been tuned into the changes in emotional health from the MBSR intervention, as many of the quotations were in the past tense and described their experiences with migraine’s impact on emotional health prior to the study. Given the small sizes limit our ability to make broad interpretations of these group comparisons, these differences highlight future areas for continued research. Finally, although the results are categorized into distinct themes, overlap and potential interdependence exist between themes, and further research could help clarify potential causality.

Of note, migraine is a disease with episodic attacks of headache and additional associated symptoms. Although many patients used the term “migraines” to describe their experiences, we converted “migraines” to “migraine attacks” throughout in an effort to highlight this important distinction.

CONCLUSION

Migraine contributes to tremendous disease burden with paramount impact on numerous domains (family, social, work/career) affecting quality of life. Migraine affects emotional health well beyond depression and anxiety, with resulting frustration, anger, guilt, and stigma. Not only is a migraine episode highly debilitating, the fear of migraine onset often creates behaviors in anticipation of a migraine attack, amplifying migraine’s effects with increased anticipatory anxiety, pain catastrophizing, isolation, and hopelessness. Difficulty concentrating, communicating, and experiencing irritability are disabling ictal symptoms that affect functionality beyond pain and the typical associated migraine symptoms (e.g., photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting). The rich insights gained from this qualitative research emphasize the importance of understanding the full impact of migraine to capture, measure, and treat the all-encompassing effects of migraine on patients’ lives. Although headache frequency and intensity play a major role in migraine, learning from patients themselves about the deep impact of migraine on their lives ensures that clinicians and researchers are able to effectively target and treat what is most important to those living with migraine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for all the participants who volunteered for this study. We are thankful for the tremendous support of Charles R. Pierce, Kate Furgurson, the Wake Forest Baptist Health Q-Pro, Timothy T. Houle, PhD, Elizabeth Loder, MD, MPH, Donald B. Penzien, PhD, and Fadel Zeidan, PhD. We appreciate the support from the Wake Forest Clinical Translational Science Institute (CTSI), the Clinical Research Unit staff and support, and the Research Coordinator Pool, funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR001420, and Harvard Catalyst research assistant Peter Douglass. We appreciate the help of the research coordinators, including Imani Randolph, Elizabeth Crenshaw, Emily Ansusinha, Georgeta Lester, Carolyn Hedrick, Sandra Norona, Nancy Lawlor, and Brittany Briceno. This study would not have been completed without the tremendous support of a multitude of students, including Nicole Rojas, Hudaisa Fatima, Jason Collier, Grace Posey, Obiageli Nwamu, Vinish Kumar, Rosalia Arnolda, Paige Brabant, Danika Berman, Nicholas Contillo, Flora Chang, Easton Howard, Camden Nelson, and Carson DeLong.

Funding information

This research was funded by the American Pain Society Grant, Sharon S. Keller Chronic Pain Research Program, (PI-Wells); NCCIH K23AT008406 (PI-Wells) and NINDS K23NS096107 (PI-Seng), American Headache Society Fellowship (PIs: Wells and Burch) and the Headache Research Fund of the John R. Graham Headache Center, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital. This research was supported in part by the Qualitative and Patient-Reported Outcomes Developing Shared Resource of the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center’s NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA012197 and the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute’s NCATS Grant UL1TR001420. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

CONFLIC T OF INTEREST

PE, SB, RA, CM, MS, GG, AB, NO, SWP, and REW have no conflicts of interest to report. RB receives an editorial stipend for serving as an Associate Editor for Neurology. NH is an employee and receives salary support from BrightOutcome, Inc. ES has consulted for GlaxoSmithKline and Click Therapeutics. DCB is a part-time employee of Vector Psychometric Group, LLC and has received grant support and honoraria from the Food and Drug Administration and the National Headache Foundation and grant support and honoraria from Allergan, Amgen, Biohaven, Lilly, Novartis, and Promius/Dr. Reddys. She serves on the editorial board of Current Pain and Headache Reports. RBL has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund. He serves as a consultant, serves as an advisory board member, has received honoraria from or conducted studies funded by Alder, Abbvie/Allergan, American Headache Society, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Teva, Inc. He receives royalties from Wolff’s Headache, 8th Edition (Oxford University Press, 2009). He holds stock or options in Biohaven and Cntrl M.

Abbreviations:

- CaMEO

Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes

- IMPAC

Impact of Migraine on Partners and Adolescent Children

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- HA

Headache Education

- HIT-6

Headache Impact Test-6

- MA

Massachusetts

- MBSR

Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction

- MIDAS

Migraine Disability Assessment Test

- NC

North Carolina

- RCTs

randomized controlled trials

- SD

Standard Deviation

- UCNS

United Council for Neurologic Subspecialties

Footnotes

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBERS

Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers: NCT01545466 and NCT02695498.

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD APPROVAL

IRB approval for this study was granted by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Wake Forest Baptist Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zebenholzer K, Andree C, Lechner A, et al. Prevalence, management and burden of episodic and chronic headaches—a cross-sectional multicentre study in eight Austrian headache centres. J Headache Pain. 2015;16(1):531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z, et al. The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2014;15(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martelletti P, Schwedt TJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. My migraine voice survey: a global study of disease burden among individuals with migraine for whom preventive treatments have failed. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Kolodner K, Stewart WF, Liberman JN, Steiner TJ. The family impact of migraine: population-based studies in the USA and UK. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(6):429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lampl C, Thomas H, Stovner LJ, et al. Interictal burden attributable to episodic headache: findings from the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buse DC, Powers SW, Gelfand AA, et al. Adolescent perspectives on the burden of a parent’s migraine: results from the CaMEO Study. Headache. 2018;58(4):512–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allena M, Steiner TJ, Sances G, et al. Impact of headache disorders in Italy and the public-health and policy implications: a population-based study within the Eurolight Project. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipton RB, Buse DC, Adams AM, Varon SF, Fanning KM, Reed ML. Family impact of migraine: development of the Impact of Migraine on Partners and Adolescent Children (IMPAC) Scale. Headache. 2017;57(4):570–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buse DC, Scher AI, Dodick DW, et al. Impact of migraine on the family: perspectives of people with migraine and their spouse/domestic partner in the CaMEO Study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(5):596–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibbs SN, Shah S, Deshpande CG, et al. United States patients’ perspective of living with migraine: country-specific results from the global “My Migraine Voice” Survey. Headache. 2020;60(7):1351–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stovner LJ, Andrée C. Impact of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight Project. J Headache Pain. 2008;9(3):139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML, et al. Life with migraine: effects on relationships, career, and finances from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache. 2019;59(8):1286–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):e273–e283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine: epidemiology, burden, and comorbidity. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):631–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41(7):646–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buse DC, Silberstein SD, Manack AN, Papapetropoulos S, Lipton RB. Psychiatric comorbidities of episodic and chronic migraine. J Neurol. 2013;260(8):1960–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: a design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312118822927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells RE, Burch R, Paulsen RH, Wayne PM, Houle TT, Loder E. Meditation for migraines: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2014;54(9):1484–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells RE, O’Connell N, Pierce CR, et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness meditation vs headache education for adults with migraine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(3):317–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saldana J The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton AB. Rapid turn-around qualitative research. Paper presented at: 16th Annual ResearchTalk Qualitative Research Summer Intensive2019; Chapel Hill, NC. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koenig CJ, Abraham T, Zamora KA, et al. Pre-implementation strategies to adapt and implement a veteran peer coaching intervention to improve mental health treatment engagement among rural veterans. J Rural Health. 2016;32(4):418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicosia FM, Kaul B, Totten AM, et al. Leveraging Telehealth to improve access to care: a qualitative evaluation of Veterans’ experience with the VA TeleSleep program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gale RC, Wu J, Erhardt T, et al. Comparison of rapid vs in-depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charmaz K Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buse DC, Lipton RB, Hallström Y, et al. Migraine-related disability, impact, and health-related quality of life among patients with episodic migraine receiving preventive treatment with erenumab. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(10):1622–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buse DC, Lipton RB, Hallstrom Y, et al. Patient-reported outcomes from the STRIVE trial: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study of erenumab in subjects with episodic migraine. Headache. 2017;57:198–199. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashina M, Brandes JL, Katsarava Z, et al. Patient-reported outcomes from the ARISE trial: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study of erenumab in subjects with episodic migraine. Headache. 2017;57:192. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rastenytė D, Mickevičienė D, Stovner LJ, Thomas H, Andrée C, Steiner TJ. Prevalence and burden of headache disorders in Lithuania and their public-health and policy implications: a population-based study within the Eurolight Project. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parikh SK, Young WB. Migraine: stigma in society. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(1):8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutberg S, Öhrling K. Migraine—more than a headache: women’s experiences of living with migraine. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(4):329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bishop KL, Holm JE, Borowiak DM, Wilson BA. Perceptions of pain in women with headache: a laboratory investigation of the influence of pain-related anxiety and fear. Headache. 2001;41(5):494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gvantseladze K, Do TP, Hansen JM, Shapiro RE, Ashina M. The stereotypical image of a person with migraine according to mass media. Headache. 2020;60(7):1465–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapiro RE. What will it take to move the needle for headache disorders? An advocacy perspective. Headache. 2020;60(9):2059–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shapiro RE, Araujo AB, Nicholson RA, et al. Stigmatizing attitudes about migraine by people without migraine: results of the overcome study. Headache. 2019;59:14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith TR, Nicholson RA, Banks JW. Migraine education improves quality of life in a primary care setting. Headache. 2010;50(4):600–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kindelan-Calvo P, Gil-Martínez A, Paris-Alemany A, et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic patient education for adults with migraine. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Med. 2014;15(9):1619–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arca KN, Starling AJ. Advocacy in headache medicine: tips at the bedside, the institutional level, and beyond. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(11):52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim S, Bae DW, Park SG, Park JW. The impact of pain-related emotions on migraine. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luedtke K, Basener A, Bedei S, et al. Outcome measures for assessing the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions in frequent episodic or chronic migraine: a Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e029855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Houts CR, McGinley JS, Nishida TK, et al. Systematic review of outcomes and endpoints in acute migraine clinical trials. Headache. 2021;61(2):263–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGinley JS, Houts CR, Nishida TK, et al. Systematic review of outcomes and endpoints in preventive migraine clinical trials. Headache. 2021;61(2):253–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cherkin DC. Are methods for evaluating medications appropriate for evaluating nonpharmacological treatments for pain?-challenges for an emerging field of research. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(3):328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banbury A, Nancarrow S, Dart J, Gray L, Parkinson L. Telehealth interventions delivering home-based support group videoconferencing: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(2):e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hahn SR, Lipton RB, Sheftell FD, et al. Healthcare provider-patient communication and migraine assessment: results of the American Migraine Communication Study, phase II. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(6):1711–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lipton RB, Hahn SR, Cady RK, et al. In-office discussions of migraine: results from the American Migraine Communication Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1145–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmes WF, MacGregor EA, Sawyer JP, Lipton RB. Information about migraine disability influences physicians’ perceptions of illness severity and treatment needs. Headache. 2001;41(4):343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Predictors of outcome in headache patients presenting to family physicians—a one year prospective study. The Headache Study Group of The University of Western Ontario. Headache. 1986;26(6):285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frymoyer JW, Frymoyer NP. Physician-patient communication: a lost art? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10(2):95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lechner CM, Partsch MV, Danner D, Rammstedt B. Individual, situational, and cultural correlates of acquiescent responding: towards a unified conceptual framework. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2019;72(3):426–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lipton RB, Hutchinson S, Ailani J, et al. Discontinuation of acute prescription medication for migraine: results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache. 2019;59(10):1762–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buse DC, Yugrakh MS, Lee LK, Bell J, Cohen JM, Lipton RB. Burden of illness among people with migraine and ≥4 monthly headache days while using acute and/or preventive prescription medications for migraine. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(10):1334–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Archibald N, Lipscomb J, McCrory DC. AHRQ technical reviews. In Resource Utilization and Costs of Care for Treatment of Chronic Headache. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (US); 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]