Abstract

Purpose of review

Short stature is a common clinical manifestation in children. Yet, a cause is often unidentifiable in the majority of children with short stature by a routine screening approach. The purpose of this review is to describe the genetic approach for evaluating short stature, challenges of genetic testing, and recent advances in genetic testing for short stature.

Recent findings

Genetic testing, such as karyotype, chromosomal microarray, targeted gene sequencing or exome sequencing, has served to identify the underlying genetic causes of short stature. When determining which short stature patient would benefit from genetic evaluation, it is important to consider whether the patient would have a single identifiable genetic cause. Specific diagnoses permit clinicians to predict responses to GH treatment, to understand the phenotypic spectrum, and to understand any associated co-morbidities.

Summary

The continued progress in the field of genetics and enhanced capabilities provided by genetic testing methods expands the ability of physicians to evaluate children with short stature for underlying genetic defects. Continued effort is needed to elaborate new genetic causes of linear growth disorders, therefore, we expand the list of known genes for short stature, which will subsequently increase the rate of genetic diagnosis for children with short stature.

Keywords: Idiopathic short stature, genetic testing, exome sequencing

Introduction

Linear growth during childhood is a process regulated and affected by the many varying factors involved, such as prenatal, nutritional, hormonal, environmental, or genetic [1–4]. Impaired linear growth has been universally defined as a child with a height standard deviation score (SDS) < −2 for their respective age. In the vast majority of short stature cases, the child appears healthy but exhibits a lower rate of linear growth, which we often refer to as “idiopathic short stature”, thereby emphasizing the unknown etiology, or “isolated short stature”, which highlights the specificity of the presenting symptom [1–4]. Short stature can occur because the child follows the familial height patterns that are non-pathological; therefore, the short stature may be of minimal concern from a medical perspective, especially when both parental heights are at a low percentile on the growth chart (familial short stature, FSS) and the child’s projected height trajectory is within the range of mid-parental height (MPH). The short stature may be naturally resolved at a later stage of development as the child may just be experiencing a delayed pubertal maturation, which results in maintaining the prepubertal growth rate and the child temporarily falling “behind the curve” (Constitutional delay of growth and development, CDGP) [1–4]. However, even after excluding the proportion of aforementioned children with non-pathologically derived short stature, the majority of children that present with short stature remain frequently without adequate explanation of the etiology during their childhood.

Although certain causes of impaired growth can be readily identifiable with a history, physical examination, and biochemical studies (such as celiac/inflammatory bowel disease, initiation of ADHD medication, hypothyroidism, growth hormone deficiency), often physicians are unable to ascertain any underlying pathogenic cause for a patient’s short stature, resulting in diagnosis of ISS [1–4]. In a recent study on the etiology of severe short stature with height SDS < −3, approximately 30% of children had ISS, by far the category taking up the largest portion of cases analyzed [5]. In the study, 20% of children had syndromic short stature and 15% had organic disease, while growth hormone deficiency, small for gestational age (SGA), and skeletal dysplasia were observed in approximately 10% of children with severe short stature. This study indicates that approximately 50% of children with severe short stature may have a genetic etiology [5].

Several large-scale genome-wide association studies have shown that adult height is inheritable and is influenced by the combined impacts from each polymorphism in the linear growth-associated genes. We could speculate that the more deleterious variants in each of these genes could significantly impair childhood linear growth, leading to short stature originating from a single genetic cause [6–7]. However, to date, the pathological role of only a small portion of these genes were identified (or proven) in childhood linear growth disorders, highlighting the need for pursuing the genetic causes of short stature and rationalizing the efforts to push genetic discovery for these genes [6–7]. As research progressed, the cost-effectiveness and utility of genetic tools improved, resulting in enhanced diagnostic capabilities for identifying both previously known and novel genetic causes of short stature [3,4]. However, clinicians are often disappointed upon receiving the results of the genetic testing because 1) the rate of identifying the causative genetic causes using these genetic approaches is still low (~30%), especially with exome sequencing (ES) [8,9] and 2) the interpretation of the results is not always easy or sometimes leaves uncertainty, discouraging them to pursue the genetic studies. In addition, short stature patients in need of genetic testing may be turned away by the approval process of insurance companies unless they have additional significant syndromic features. However, despite these hurdles, making a genetic diagnosis for short stature brings many merits to patient care, such as diagnosis-based management, identifying associated co-morbidities, predicting the response to growth hormone, genetic counseling, and advancement in the field of relevant medical science [3]. Herein, we review updates on the genetic testing for short stature including how we should approach patients with genetic testing for short stature, challenges of genetic testing, and the progresses made in the past year.

Understanding genetic approaches for short stature

Traditional medical evaluations for children with short stature have focused on hormonal etiologies, chronic disorders, and a small number of genetic causes. Prior research indicates that routine comprehensive screening has limited power to identify the cause in asymptomatic short children [10]. It has been suggested that genetic etiology may make up a larger portion of the causes of ISS during childhood [5], among them, approximately 22% of children with ISS may have a subtle skeletal dysplasia [3]. Previously identified genetic causes of linear growth disorders are highly heterogenous affecting various cellular pathways, and in general, these genetic variants impact growth plate chondrogenesis [7].

When genetic testing is considered for children with short stature, it is important to understand that patients may have multiple coexisting variants that minimally impact on an individual level but cumulatively lead to mildly impaired linear growth [11], which is termed “oligogenic” or “polygenic” (usually considered in patients with FSS) rather than a single genetic variant causing a child’s short stature, which is termed “monogenic”. Current genetic approaches are designed to identify the latter, monogenic, cases [11]. Therefore, when considering using a proper genetic approach, it is critical to select patients who likely have a single genetic cause of short stature for genetic testing. If this exclusion criteria is not established, genetic testing may easily fail to identify the cause for short stature.

If all biochemical studies show negative results and patients do not seem to have a particular phenotype, difficulties arise in determining the underlying cause of short stature solely based on patient history and physical exam. In this situation, clinicians may employ genetic testing, such as karyotyping for Turner syndrome, chromosomal microarray for chromosomal structural abnormalities, targeted gene panels for suspected genes (or accompanying symptoms), and ES for a broader genetic screening. In practice, how do we easily recognize patients with short stature due to one particular genetic cause? One of the methods to ascertain whether a patient has short stature due to a single genetic cause is through scrutinization of the parental heights (Figure 1). In addition to the parental heights, the pedigree of the extended family will help distinguish monogenic from oligo/polygenic conditions, especially when one parent also has short stature or the short stature was inherited in an X-linked fashion in boys.

Figure 1. Considerations for genetic testing based on parental heights.

ISS, idiopathic short stature; SDS, standard deviation score; TFT, thyroid function test; LFT, liver function test; PAH, predicted parental height; MPH, mid-parental height; FSS, familial short stature; CDGP, constitutional delay of growth and puberty.

If both parental heights are in a low percentile and the patient’s height deficit is similar to their parental height or the predicted adult height (PAH) is close to the MPH, then this patient may have FSS. Unfortunately, identifying the genetic cause of patients with FSS would be difficult, as mentioned above, because the short stature is likely caused by more than one genes, each contributing incremental impacts that produce a mild effect in conjunction together. However, if both parental heights are in a low percentile but the patient’s height deficit is more profound (< −2.5 SDS), then this patient may carry a single genetic defect [12].

If the patient has a similar height deficit as one parent, then the causal genetic defect for short stature may have been inherited from the parent in an autosomal dominant fashion. In this case, there may be multiple family members with short stature in the extended family as seen in patients with ACAN or SHOX mutations [13, 14]. Recently, Stavber et al. set out to determine whether diagnostic indicators, such as an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and the presence of advanced bone age could identify aggrecanopathy in children. The study successfully identified pathogenic ACAN variants in the study cohort (37.5%) and discovered six novel mutations [13].

When both parents have normal height but the patient has ISS, then there are several considerations to take into account. If the patient has a significant delay in bone age, a family history of delayed puberty, and a PAH close to MPH, then this patient may have CDGP. Otherwise, the patient may have a genetic cause that possibly occurred de novo, in an autosomal recessive or X-linked fashion (if the patient is a boy) [15].

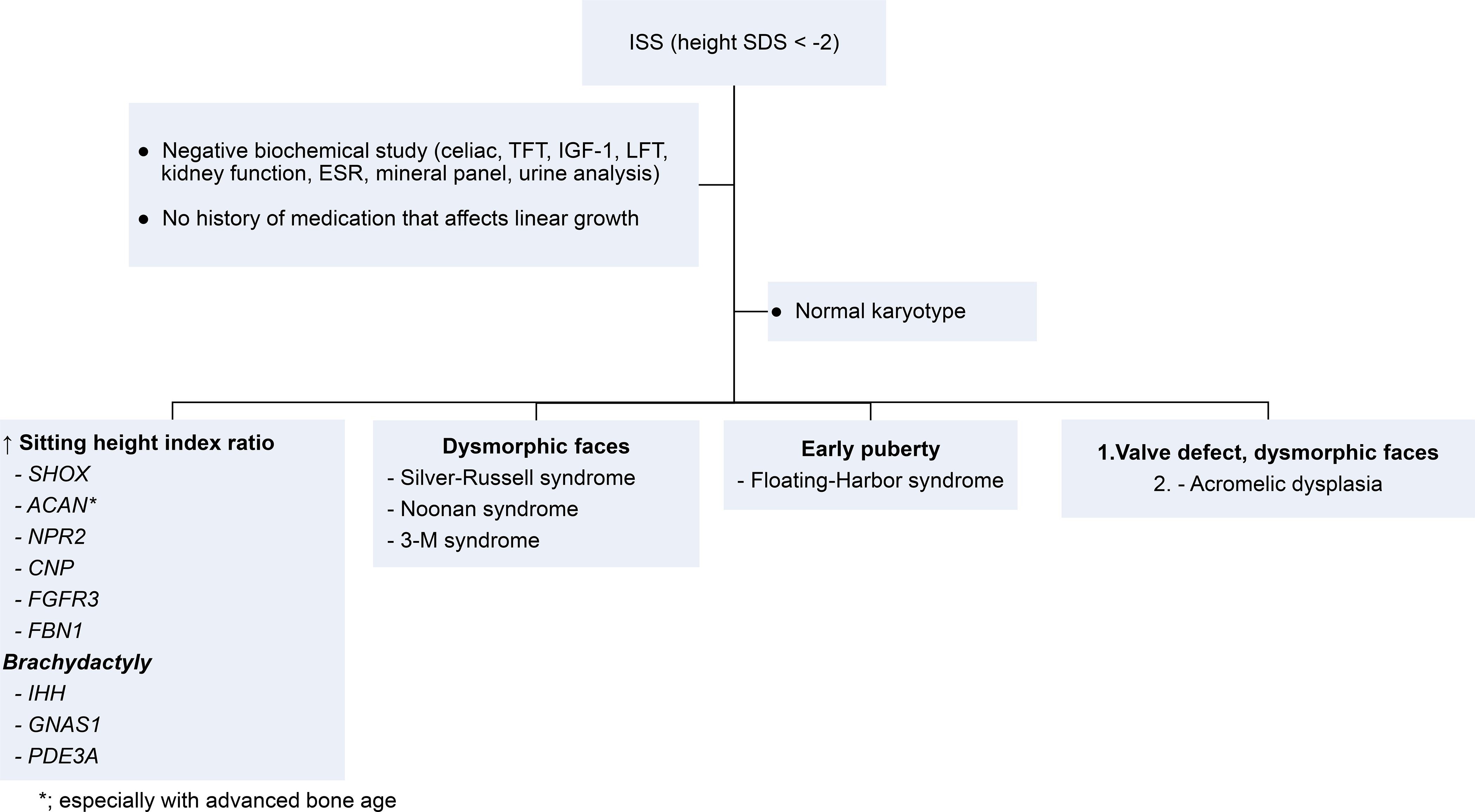

After assessing the possibility of genetic causes of ISS in patients, patient characteristics can also provide a clue for a certain genetic defect (Figure 2). Disproportionate short stature, especially when sitting height index (sitting height/standing height ratio) is greater than 95%, suggests genetic defects in SHOX, ACAN, NPR2, CNP, FGFR3, FBN1 or other genetic defects in growth plate chondrogenesis [16–17]. The presence of brachydactyly may suggest defects in IHH, GNAS1, PDE3A [19]. Each gene may be tested as a targeted gene sequencing or as part of gene panel at a CLIA-certified laboratory. If the patient has dysmorphic faces, then clinicians may order specific genetic testing corresponding to the syndrome, such as Silver-Russell, Noonan, or 3-M syndrome [20]. Certain genetic testing, such as SHOX or Silver-Russell syndrome, may be challenging because the genetic cause may not be found in a protein-coding region (e.g. SHOX) [14] or the genetic cause is not only found in methylation defect but also the variants in HMGA2 or IGF2 [21–22], which means a couple of different genetic testing should be considered to fully cover the genetic causes of Silver-Russell syndrome when it is suspected. If the patient with short stature has an earlier onset of puberty, then Floating-Harbor syndrome may be considered [23]. Although rare, patients with severe short stature, dysmorphic facies, and cardiac valvular defect may have acromelic dysplasia caused by defect in microfibrillar network, an important extracellular matrix component [24]. For patients with a history of significant developmental delay or intellectual disabilities, chromosomal microarray or referral to a geneticist may be considered [25]. For patients exhibiting significant short stature with or without accompanying physical features, exome sequencing may be used to screen for possible pathogenic changes in genes [11].

Figure 2. Clinical clues that may indicate a certain genetic cause.

The listed genes and syndromes are the examples. ISS, idiopathic short stature; SDS, standard deviation score; TFT, thyroid function test; LFT, liver function test.

Challenges of genetic testing for short stature

While targeted gene panel or ES may be considered in clinical setting for patients with short stature, clinicians do not always receive interpretable results, especially when the identified variant is not previously reported in patients. In this case, the guidelines from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) are used to categorize the pathogenicity of the identified variants [26]. The potential impact of the identified variant is determined based on the population frequency, prediction of deleteriousness by silico prediction, cellular function, co-segregation in the family, and the known co-existing phenotype. Clinicians often receive results stating that the identified variants is of “unknown significance”, which means that the identified variant may or may not be the cause of short stature, leaving a decision of correlating the identified variant to short stature to clinicians. Sequencing the parents’ DNA may clarify the pathogenicity of the variant if it occurred de novo or if it was inherited from an affected or unaffected parent although this strategy is not always feasible. Recently, Hauer et al. demonstrated the power of family-based ES. Considering only genes previously associated with poor linear growth, the diagnostic yield with systematic phenotyping and targeted testing was 13.6%. However, the diagnostic rate increased to 33% when additional family-based exome sequencing was performed [15]. As the cost of clinical ES becomes cheaper, including parental DNA during the evaluation of patient’s genetic testing as a standard approach may improve the diagnostic rate and the accuracy in the future.

Updates on the genetics of short stature

There is on-going effort to continue identifying genetic variants in novel genetic causes in children with ISS [27–28]. One of the benefits of genetic diagnosis is to offer the opportunity to predict patient responses to GH treatment and improve precision medicine. Notably, Plachy et al. observed that compared to children harboring SHOX defects, children with NPR2 defects suggested significantly greater height improvement after GH therapy similar to patiets with SHOX deficiency [29]. Moreover, the type of mutation in a particular gene can also influence the efficacy of GH treatment. A recent study suggested that final adult height in patients who were homozygous for NPR2 mutations did not improve after GH therapy, while GH treatment in patients with heterozygous mutations effectively increased height [30–31]. Consistent with the previous reports, patients with the genetic variants in ACAN responded beneficially to GH therapy [32] and prepubertal children with short stature due to variants in IHH also showed favorable responses to GH therapy [18].

Conclusion

Childhood linear growth is a complex process influenced by numerous factors. Many children classified under ISS have underlying genetic causes for their short stature. Recent advances in molecular technologies are allowing for improved diagnosis for ISS patients through genetic approaches. Although the list of known genes for short stature remains limited to a small number, genetic testing can still serve as a useful tool to identify pathogenic variants responsible for short stature. As more novel genetic causes are identified and reported, the use of targeted gene panel or clinical ES will continue to improve in the clinical setting. Therefore, further research should continue to identify additional novel genetic causes in children with short stature.

Key points.

When considering using a proper genetic approach, it is critical to select patients who likely have a single genetic cause of short stature for genetic testing.

Including parental DNA during the evaluation of patient’s genetic testing as a standard approach may improve the diagnostic rate and the accuracy in the future.

Genetic diagnosis could offer the opportunity to predict patient responses to GH treatment and improve precision medicine.

Financial support and sponsorship

The research is supported by an NIH intramural research grant.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Polidori N, Castorani V, Mohn A, Chiarelli F. Deciphering short stature in children. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;25(2):69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inzaghi E, Reiter E, Cianfarani S: The Challenge of Defining and Investigating the Causes of Idiopathic Short Stature and Finding an Effective Therapy. Horm Res Paediatr 2019;92:71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray PG, Clayton PE, Chernausek SD. A genetic approach to evaluation of short stature of undetermined cause. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018July;6(7):564–574. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collett-Solberg PF, Ambler G, Backeljauw PF, et al. Diagnosis, Genetics, and Therapy of Short Stature in Children: A Growth Hormone Research Society International Perspective. Horm Res Paediatr. 2019;92(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kärkinen J, Miettinen P, Raivio T, & Hero M (2020). Etiology of severe short stature below −3 SDS in a screened Finnish population, European Journal of Endocrinology, 183(5), 481–488. * This study reports the identified causes of severe short stature in children confirming that the most common cause of severe short stature is genetic.

- 6.Vasques GA, Andrade NLM, Jorge AAL. Genetic causes of isolated short stature. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2019February;63(1):70–78. PMID: 30864634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yue Shanna, Whalen Philip, Jee Youn Hee. Genetic regulation of linear growth. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2019March;24(1):2–14. PMID: 30943674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazaridis KN, McAllister TM, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, et al. Implementing individualized medicine into the medical practice. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014;166C: 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji Jianling, Shen Lishuang, Bootwalla Moiz, et al. A semiautomated whole-exome sequencing workflow leads to increased diagnostic yield and identification of novel candidate variants. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2019April1;5(2):a003756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sisley S, Trujillo MV, Khoury J, Backeljauw P. Low Incidence of Pathology Detection and High Cost of Screening in the Evaluation of Asymptomatic Short Children. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2013October;163(4):1045–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dauber A Genetic Testing for the Child With Short Stature—Has the Time Come To Change Our Diagnostic Paradigm? The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2019July1;104(7):2766–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plachy Lukas, Strakova Veronika, Elblova Lenka, et al. High Prevalence of Growth Plate Gene Variants in Children With Familial Short Stature Treated With GH. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019October1;104(10):4273–4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stavber L, Hovnik T, Kotnik P, et al. High frequency of pathogenic ACAN variants including an intragenic deletion in selected individuals with short stature. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020March;182(3):243–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funari MFA, Barros JS, Santana LS, et al. Evaluation of SHOX defects in the era of next-generation sequencing. Clin Genet. 2019September;96(3):261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Zhuo, Sun Yu, Fan Yanjie, et al. Genetic Evaluation of 114 Chinese Short Stature Children in the Next Generation Era: a Single Center Study. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;49(1):295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauer NN, Popp B, Schoeller E, et al. Clinical relevance of systematic phenotyping and exome sequencing in patients with short stature. Genet Med. 2018June;20(6):630–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jee YH, Baron J, Nilsson O. New developments in the genetic diagnosis of short stature. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018August;30(4):541–547. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000653.PMID: 29787394; PMCID: PMC7241654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freire BL, Homma TK, Funari MFA, et al. Multigene Sequencing Analysis of Children Born Small for Gestational Age With Isolated Short Stature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019June1;104(6):2023–2030. * This study identifies the genetic variants in known genes to cause short stature in children who were born SGA but continue to have short stature.

- 19.Vasques GA, Funari MFA, Ferreira FM, et al. IHH Gene Mutations Causing Short Stature With Nonspecific Skeletal Abnormalities and Response to Growth Hormone Therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018February1;103(2):604–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dauber A, Rosenfeld RG, Hirschhorn JN. Genetic evaluation of short stature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014September;99(9):3080–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hübner CT, Meyer R, Kenawy A, et al. HMGA2 Variants in Silver-Russell Syndrome: Homozygous and Heterozygous Occurrence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020July1;105(7):dgaa273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia CL, Lyu Y, Li C, Li H, et al. Rare De Novo IGF2 Variant on the Paternal Allele in a Patient With Silver-Russell Syndrome. Front Genet. 2019November15;10:1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang S, Chen S, Qin H, et al. Novel genotypes and phenotypes among Chinese patients with Floating-Harbor syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019June14;14(1):144. * This study reports the case series of Floating-Harbor syndrome that may be underdiagnosed in our clinical setting.

- 24.Marzin Pauline, Thierry Briac, Dancasius Andrea, et al. Geleophysic and acromicric dysplasias: natural history, genotype–phenotype correlations, and management guidelines from 38 cases. Genetics in Medicine 2021. 23:331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moeschler John B, Shevell Michael, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics. Clinical genetic evaluation of the child with mental retardation or developmental delays. Pediatrics. 2006June;117(6):2304–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards Sue, Aziz Nazneen, Bale Sherri, et al. On behalf of the ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015May; 17(5): 405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perchard R, Murray PG, Payton A, et al. Novel Mutations and Genes That Impact on Growth in Short Stature of Undefined Aetiology: The EPIGROW Study. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(10):bvaa105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu X, Guo R, Guo J, et al. Parallel Tests of Whole Exome Sequencing and Copy Number Variant Sequencing Increase the Diagnosis Yields of Rare Pediatric Disorders. Front Genet. 2020;11:473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plachy L, Dusatkova P, Maratova K, et al. NPR2 Variants Are Frequent among Children with Familiar Short Stature and Respond Well to Growth Hormone Therapy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2020March1;105(3):e746–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hanley PC, Kanwar HS, Martineau C, Levine MA. Short Stature is Progressive in Patients with Heterozygous NPR2 Mutations. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2020October1;105(10):3190–202. * The study describes the characteristics of linear growth in patients with heterozygous NPR2 mutations.

- 31.Ke X, Liang H, Miao H, et al. Clinical Characteristics of short stature patients with NPR2 mutation and the therapeutic response to rhGH. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020November17;106(2):431–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang H, Miao H, Pan H, et al. Growth-Promoting Therapies May Be Useful In Short Stature Patients With Nonspecific Skeletal Abnormalities Caused By Acan Heterozygous Mutations: Six Chinese Cases And Literature Review. Endocr Pract 2020November;26(11):1255–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]