Abstract

Public engagement in priority-setting for health is increasingly recognized as a means to ensure more ethical, inclusive and legitimate decision-making processes, especially in the context of Universal Health Coverage where demands outweigh the available resources and difficult decisions need to be made. Deliberative approaches are often viewed as especially useful in considering social values and balancing trade-offs, however, implementation of deliberative engagement tools for priority-setting is scant, especially in low- and middle-income settings. In order to address this gap, we implemented a context-specific public deliberation tool in a rural community in South Africa to determine priorities for a health services package. Qualitative data were analysed from seven group deliberations using the engagement tool. The analysis focused on understanding the deliberative process, what the participants prioritized, the reasons for these selections and how negotiations took place within the groups. The deliberations demonstrated that the groups often considered curative services to be more important than primary prevention which related to the perceived lack of efficacy of existing health education and prevention programmes in leading to behaviour change. The groups engaged deeply with trade-offs between costly treatment options for HIV/AIDS and those for non-communicable disease. Barriers to healthcare access were considered especially important by all groups and some priorities included investing in more mobile clinics. This study demonstrates that deliberative engagement methods can be successful in helping communities balance trade-offs and in eliciting social values around health priorities. The findings from such deliberations, alongside other evidence and broader ethical considerations, have the potential to inform decision-making with regard to health policy design and implementation.

Keywords: Priority-setting, community participation, resource allocation, decision-making, health care

Key Messages.

Deliberative engagement methods for including the public in the decision-making process for the development of health policy and services are important to ensure more ethical, legitimate and sustainable priority-setting

Communities can engage in trade-offs within the context of limited resources using a deliberative approach

Community priorities are may differ from priorities of experts and these should be considered when designing health service packages

Findings from such deliberative engagements should complement other cost effectiveness evidence and broader ethical considerations to determine priorities for Universal Health Coverage

Introduction

Public engagement in setting priorities for health refers to the active involvement of communities in the decision-making activities for the development of health policies and services (Florin and Dixon, 2004). This approach is increasingly recognized as a means to complement standard approaches like economic evaluations and to ensure more ethical, inclusive and legitimate decision-making processes (Terwindt et al., 2016). It is especially important as countries move towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC) in contexts where the demands on healthcare resources far outweigh the available resources (World Health Organisation, 2014; Weale et al., 2016).

The concept of public engagement is rooted in deliberative democratic principles which uphold the value of involving those whose lives are impacted by a particular decision in its development (Abelson et al., 2003). The inclusion of community voices in the decision-making process has potential benefits for both decision makers and communities. It ensures transparency which in turn promotes public acceptability of the decision-making process and its outcomes and increases the likelihood of successful policy implementation (Caddy and Vergez, 2001; Scuffham et al., 2014). It can also more accurately reflect communities’ health needs as well as barriers and facilitators to healthcare which can lead to more appropriate resource allocation decisions (Oladeinde et al., 2020).

Different methods exist for engaging the public in a priority-setting but deliberative approaches are viewed as more meaningful in considering social values, balancing trade-offs and developing consensus (Carman et al., 2013). Some key components of public deliberation include providing participants with factual information that enables a shared knowledge base, ensuring that individuals with diverse perspectives are represented and creating a setting where values and opinions can be voiced and challenged (Abelson et al., 2013). Deliberative methods encourage dialogue and debate and at times make use of tools that demonstrate the consequences of trade-offs. This is in contrast to non-deliberative approaches like surveys, opinion polling, discreet choice experiments, and others where the aim is to determine ‘top of mind’ responses and not to deeply consider and discuss issues (Solomon and Abelson, 2012).

There are a number of deliberation models. Some of these include community meetings, public panels, and deliberative forums (Abelson et al., 2013). In some countries where there are formal priority-setting institutions in place citizen groups play a role in the decision-making process. In Thailand, public representatives are involved in different stages of health benefit package development as part of the Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Programme (HITAP) (Slutsky et al., 2016).

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) makes use of a citizens’ council of representatives of the public, which provides the public’s views on non-technical considerations for benefit inclusion by the National Health Service (NICE, 2013). This type of engagement known as ‘minipublics’ has been used in other settings including Canada and Australia (Abelson et al., 2013). In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there is limited public deliberation in decision-making (Alderman, 2013).

South Africa is moving towards UHC which is slated to be financed through a national health insurance (NHI) scheme. Difficult resource allocation decisions will need to be made in order to improve health outcomes. In the interim, the challenge of priority-setting for health continues to prevail under the existing health system structure.

Currently, the health system is divided into a public and a private sector. The public sector is poorly resourced and overburdened serving 83% of the population. The private sector serves 17% of the population who derive benefit from private healthcare insurance (Competition Commission, 2019). Within the public health system, each of the nine provincial governments is responsible for service delivery decisions and the provision of healthcare services via a district-based healthcare model but are reliant on National Government for unconditional transfers or conditional grants to finance these healthcare services (Edoka and Stacey, 2020). The disproportionately low resource availability in the public sector relative to the private health sector is inequitable as more than half of financial and human resources are allocated to the private sector (Government of the Republic of South Africa, 2018).

Since 1994, South Africa is governed by its progressive Constitution which upholds participatory democratic principles and considers public engagement in the legislative process a constitutional requirement (Government of the Republic of South Africa, 1996). Various policy documents further entrench these principles. The National Policy Framework on Public Participation states that communities should influence decision-making, and The Parliamentary Public Participation Model asserts that ‘the intention of public participation and involvement in democratic processes is primarily to influence decision-making processes that reflects the will of the people’ (South African Legislative Sector, 2013; NCOP’, 2019). With regard to health, public engagement in priority-setting is formalized in the National Health Act 61 of 2003 (Amendment Act 12 of 2013), which makes provision for the establishment of community health committees (National Department of Health, 2003). The intention is that these committees ensure public participation in the priority-setting process for local clinics, but in reality, this does not happen (Padarath and Friedman, 2008). At both the national and provincial/local levels any public engagement that does occur is typically a passive event. It is not deliberative in nature and does not allow for the interrogation of what trade-offs the public might be willing to make within a constrained budget.

Despite the recognition of the importance of public engagement in priority-setting for health in South Africa, there are limited tools and applications that enable a deliberative approach and where communities are able to consider resource implications and balance individual and societal values in reaching consensus regarding trade-offs. This article focuses on the application of a modified deliberative engagement tool in a South Africa rural setting. It explores the group deliberations, what issues were prioritized by community members, the reasons for these selections and how negotiations took place within the groups. This is the first time a deliberative engagement tool has been implemented in South Africa which considers health priorities and trade-offs in the context of limited resources.

Methods

Study site

The Agincourt Health and Socio-Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) study area (https://www.agincourt.co.za/) is located in Bushbuckridge municipality in Mpumalanga Province. The area is typical of rural South Africa as it fits into the definition by the Comprehensive Rural Development Framework of

‘settlements in the former apartheid homelands, with no major economic base apart from migrant labour and remittances, typified by poverty and underdevelopment and where traditional authorities operate a land tenure system’ (Twine et al., 2016)

It has a population of ∼120 000 and life expectancy at birth is 61 for males and 70 for females (Kahn et al., 2012). There are two health centres, six satellite clinics and three district hospitals within 20–60 km from the villages. Sanitation systems are inadequate with pipe-borne water unavailable to 47% of the 20 000 households (Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System, 2020, unpublished data). Electricity is unaffordable for most and few tarred roads exist. Every village has at least one primary school and most have a high school but the quality of education is poor (Twine et al., 2016) with 54.9% of adults having passed matric. Unemployment rates are high and many households are dependent on government grants (Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System, 2020, unpublished data).

The deliberative engagement exercise

The Choosing All Together (CHAT) tool, which was originally developed by the US National Institutes for Health and Michigan State University, is a game-like exercise and aims to facilitate a deliberative and interactive process that encourages group decision-making as participants grapple with trade-offs (Goold et al., 2005). During the exercise, a trained facilitator guides participants through different rounds where they distribute a limited number of stickers on a board as they select from a range of options. The stickers, which represent the available budget, are only able to cover ∼60% of the options on the board.

The tool was modified for use in Bushbuckridge. This modification process included an iterative participatory approach that relied on policy analysis and engagement with experts and community members to identify health topics and related interventions specific to the Bushbuckridge context. This process is described in detail elsewhere (Tugendhaft et al., 2020). The outcome of the modification process was a context-specific bilingual CHAT board which included seven health topics/issues and costed options within each topic/issue to select from as part of a health services package through the allocation of funds represented by stickers.

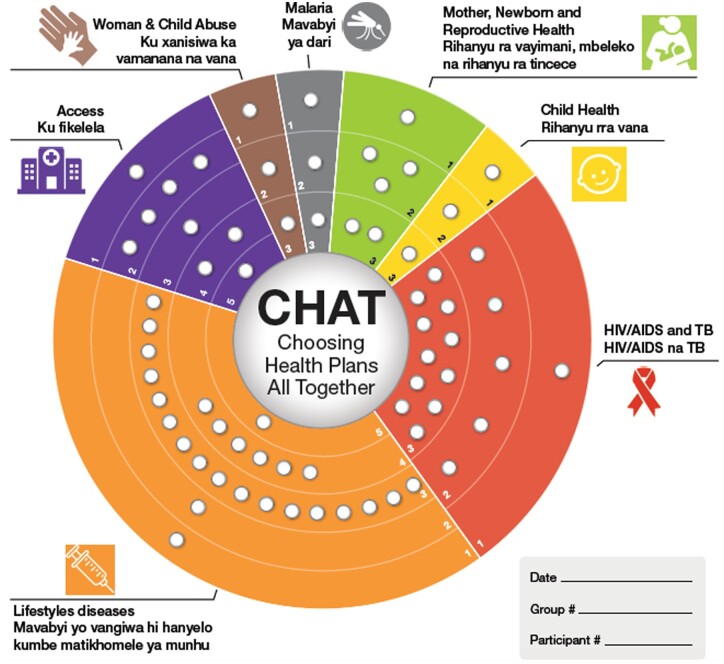

The CHAT SA board is shown in Figure 1, and the health package options are summarized in Table 1. The board is divided into different pie slices with different icons for each slice. Each pie slice represents a health topic or issue. The slices are further divided according to different categories of interventions. Interventions were grouped together and categorized using the common classification of the level of care for health interventions used in the South African health system: health promotion, prevention, diagnosis (screening), treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care (National Department of Health, 2003, 2015). The access slice included five unique categories. The total cost of the package of interventions is approximately R2 billion ($123 million) represented by 67 holes and each category of interventions per health topic/issue has a specific cost depicted by the sticker holes. Participants received 35 stickers which represented the funds they had available to allocate and that were able to cover 52% of the options on the board. This allocation was based on a starting point of 60% of stickers drawing on past CHAT exercises and was revised to allow for more meaningful rationing in the context of this specific board.

Figure 1.

CHAT SA board as adapted for use in Bushbuckridge in rural South Africa. Originally published in Tugendhaft et al. (2020).

Table 1.

Topics/issues and specific interventions of the CHAT board

| Mother, new-born and reproductive health (MNRH) |

| 1: Education and information |

| Two-month long media campaign on antenatal care (Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System) |

| Two-month long media campaign targeted at adolescents |

| Sex and reproductive education at schools |

| Mobile messaging for pregnant women |

| 2: Prevention and screening |

| Cervical cancer screening (three per lifetime) |

| HPV vaccine at schools |

| Contraceptive provision at schools |

| Improve and provide more ANC-training of healthcare workers in basic ANC |

| Exclusive breastfeeding—promotion and access to lactation specialists |

| Complementary feeding-demonstrations |

| 3: Treatment |

| Expanded services for termination of pregnancy—make available in communities. |

| Dedicated obstetric ambulances |

| Maternity waiting homes |

| Labour and delivery management |

| Emergency care for mothers and new-born |

| Child health |

| 1: Education and information |

| Media campaigns for immunization and handwashing |

| Workshops on child health |

| 2: Prevention |

| Hand washing promotion in community |

| Provision of food supplements for malnutrition and education |

| Immunisations (PHC level) |

| 3: Treatment |

| ORS for diarrhoea |

| Oral antibiotics: case management of pneumonia in children |

| HIV/AIDS and TB |

| 1: Education and information |

| 2 months long media campaign |

| 1 education workshop per year in every secondary school |

| 2: Prevention and screening |

| Increase provision of condoms |

| Youth friendly MMC services—include school friendly hours |

| Testing for HIV exposed babies |

| HIV counselling and Testing |

| Making HIV counselling and testing youth friendly (training; extra hours) |

| 3: Treatment |

| ART and mobile messaging reminders for adherence |

| Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (ARVs and breastfeeding choices) |

| TB treatment |

| Home based care |

| STI treatment |

| Youth Care Club |

| Lifestyle diseases (diabetes, hypertension, cancer) |

| 1: Education and information |

| Two-month long media campaign on NCDs |

| Educational workshop on lifestyle diseases at community level |

| 2: Prevention and screening |

| School vegetable garden |

| Increase screening and counselling in communities |

| 3: Chronic medication |

| Diabetic medication |

| Hypertension medication |

| Mobile messaging for adherence |

| 4. Treatment for complications and rehabilitation |

| Retinopathy |

| Dialysis |

| Amputations |

| Chemotherapy and radiation |

| Rehab session for stroke patients |

| 5: Palliative care |

| Palliative care (in-patient) |

| Palliative home based care |

| Access |

| 1: Improve staff attitudes (especially around FP services for adolescents) and improve management and M&E in clinics |

| 2: Make clinics operational for longer hours |

| 3: Increase number of mobile clinics from 5 to 10 |

| 4: Chronic Medicines (ARVs, diabetes meds, hypertension meds) available at community health centres |

|

5: Increase number of nurses in clinics and more pharmacists in clinics to dispense meds |

| Woman and child abuse |

| 1: Education and information |

| Education/life skills for children and adolescents, workshops on gender |

| Media messaging |

| Training and support workshops for families |

| 2: Management of rape and abuse |

| Care and support programmes, including counselling and comfort kit |

| Training of nurses |

| 3: Treatment |

| Treatment of injuries at clinics |

| PEP, 4 weeks PEP |

| Malaria |

| 1: Education and information |

| Annual education campaign |

| 2: Prevention and screening |

| ITN and indoor residual spraying |

| Screening at clinics |

| 3: Treatment |

| antimalarial medication for uncomplicated cases |

The categories and specific interventions for each category were explained in detail in a user manual written in simple language in the local language (Shangan) that accompanied the CHAT SA board. The detail provided included descriptions of the interventions, delivery mechanism and the cost of the intervention in sticker value. The manual made it clear that interventions did not overlap with one another and were independent of one another—i.e. one category of intervention (e.g. treatment for Malaria) could be selected without selecting another category under the same topic (e.g. prevention and screening for Malaria).

Participants

Sixty-three individuals participated in seven group deliberations using CHAT, with 6–11 individuals in each group. Table 2 shows the group composition in terms of age and gender of the seven groups.

Table 2.

Group composition in terms of gender and age

| G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | G6 | G7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 7 |

| Female | 5 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Age range in years | 37–62 | 30–67 | 30–55 | 20–28 | 20–42 | 40–66 | 48–67 |

| Mean age in years | 42 | 43 | 39 | 23 | 25 | 52 | 55 |

Table 3Participant characteristics

| Participants characteristics (N = 63) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | n | % |

| Age | ||

| >35 | 35 | 56 |

| <35 | 28 | 44 |

| Gender | ||

| M | 27 | 43 |

| F | 36 | 57 |

| Education | ||

| No schooling | 7 | 11 |

| Primary school | 10 | 16 |

| Some high school | 26 | 41 |

| Completed high school (Matric) | 15 | 24 |

| Tertiary | 5 | 8 |

| Household income | ||

| ZAR 3000 ($185) and below | 36 | 57 |

| ZAR3001–5000 ($186-309) | 17 | 27 |

| >ZAR5000 ($309) | 10 | 16 |

| Income source | ||

| Government grants | 19 | 30 |

| Employment | 11 | 17 |

| Grants and employment | 23 | 37 |

| Other | 10 | 16 |

Sampling and recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to include participants from a range of six villages. These villages included three with clinics in the village and three without; three with tarred roads and three with dirt roads in order to ensure inclusion of villages with different levels of development as well as different barriers to accessing healthcare. The participants were selected to ensure a mix of females and males in each of the groups except for two which included one all-male group and another group which included predominantly females. The participants were also selected based on age in order to ensure a mix of age ranges. Seventy participants were recruited face to face by experienced fieldworkers who explained the purpose of the study and invited them to participate. The final number of participants comprised 63.

Study procedures

During each of the seven groups, after the facilitator explained the board, participants individually allocated the stickers to the health issues and interventions that they perceived to be the highest priorities for their own family (round 1). Once this was complete the group completed a board collectively in terms of their priorities for the entire community of Bushbuckridge (round 2: group round). The group rounds were led by a trained community facilitator who was guided by a detailed script (Supplementary Appendix A). The groups were expected to reach a consensus about how to allocate the stickers through a majority vote. The entire deliberation process was audio-recorded with consent from participants. Scenario cards were used by the facilitator to assist participants in thinking through the implications of the decisions that they made. During the final round (round 3), participants were again asked to complete the exercise individually thinking about which priorities they believed were most important for their own family. The entire exercise took half a day with the deliberations during the group round taking ∼2 h to complete.

An informed consent process was undertaken at the recruitment stage. Separate consent was obtained for audio recording. Participants were given a participant number in order to maintain their anonymity.

Data analysis

This article focuses on the verbatim transcripts from the audio-recordings of the group rounds to understand the deliberative process, what the priorities were, why some were selected over the others and how negotiations took place within the groups. The verbatim transcriptions were translated from the local language, Shangaan, into English. Content analysis was conducted. Initial codes were developed deductively based on the health topics/issues on the CHAT board. Sub-codes were developed based on the interventions under each health topic/issue and were classified according to promotion (education); prevention; diagnosis (screening); treatment; rehabilitation; palliative care. Inductive codes were identified through deep readings of the transcripts and definitions were developed. Inductive codes were mostly linked to the CHAT deliberative process. These codes included deliberations; trade-offs; resource allocation; and shift in prioritization.

Codes were reviewed by a second coder and revisions were made for greater clarity through discussions. The codes were then applied systematically to all transcripts supported by MAXQDA 20.

Results

Participant characteristics

The participants (n = 63) ranged from age 20 to 67 years with a mean age of 39 years. Fifty-seven percent were female and 43% male; 41% had some degree of secondary education but only 24% had completed high school (Matric). Most of the participants had a household income of ZAR3000 ($200) or less per month with 30% receiving government grants and 37% relying on a combination of government grants and either formal or informal employment.

Table 4 shows the final group choices for each health topic/issue and intervention category as well as the percentage of stickers (budget) that was required to cover each intervention category. The presence of an asterisk within the table demonstrates that the option was selected by the group or was not selected where an asterisk is absent. Every group selected a spread of some education, prevention and treatment although some treatment options were more prevalent. None of the groups selected palliative care, which only featured under non-communicable diseases (Lifestyle 5), nor did they select Access level 4 which was making chronic medication available at community health centres. Three areas that were picked by 6 of the 7 groups were treatment for HIV/AIDS and TB, prevention under child health which included food supplementation and immunizations, and Access level 3 which was increase the number of mobile clinics.

Table 4.

Group choices of interventions

| Health topic/issue displayed on the CHAT Board | % of stickers (budget) | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | G6 | G7 | Total number of groups selecting the topic/issue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Maternal, neonatal and reproductive health (MNRH) 1 (education) |

1.5 | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||

| MNRH 2 (prevention and screening) | 4.0 | * | * | 2 | |||||

| MNRH 3 (treatment) | 3.0 | * | * | 2 | |||||

| Child health 1 (education) | 1.5 | * | * | 2 | |||||

| Child health 2 (immunisations, food parcels) | 1.5 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | |

| Child health 3 (treatment- ORS and antibiotics) | 1.5 | * | * | * | 3 | ||||

| HIV/AIDS and TB 1 (education) | 1.5 | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||

| HIV/AIDS and TB 2 (counselling and testing, condoms) | 8.0 | * | * | 2 | |||||

| HIV/AIDS and TB 3 (ARVs and TB treatment) | 16.0 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | |

| Lifestyle diseases 1 (education) | 1.5 | * | * | 2 | |||||

| Lifestyle diseases 2 (prevention and screening) | 1.5 | * | * | * | 3 | ||||

| Lifestyle diseases 3 (chronic medication) | 25.0 | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||

| Lifestyle diseases 4 (tx for complications) | 9.0 | * | * | * | 3 | ||||

| Lifestyle diseases 5 (palliative care) | 1.5 | 0 | |||||||

| Access 1 (staff attitudes) | 1.5 | * | * | * | 3 | ||||

| Access 2 (clinics open for longer) | 6.0 | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||

| Access 3 (mobile clinics) | 1.5 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | |

| Access 4 (chronic medication at community centres) | 3.0 | 0 | |||||||

| Access 5 (increase number of nurses) | 1.5 | * | 1 | ||||||

| Women and child abuse 1 (education) | 1.5 | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||

| Women and child abuse 2 (management and counselling) | 1.5 | * | * | * | 3 | ||||

| Women and child abuse 3 (treatment) | 1.5 | * | * | * | * | 4 | |||

| Malaria 1 (education) | 1.5 | * | * | * | 3 | ||||

| Malaria 2 (prevention and screening) | 1.5 | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | ||

| Malaria 3 (treatment) | 1.5 | * | * | * | * | 4 |

Selected.

The results from the qualitative analysis help to understand the considerations behind the priorities, what types of negotiations took place, and what trade-offs were made within the groups in order to allocate the budget to a particular issue and intervention category.

Education vs prevention vs treatment trade-offs: medicalization of healthcare

Although all of the groups chose a spread of treatment, education and prevention options, much of the deliberations focused on the benefit of treatment options versus education and/or prevention.

Education/prevention as insufficient in leading to behaviour change

There was an overriding view across all groups that even with education and prevention programmes, disease would still be prevalent. This was influenced by the perception that existing health education and prevention programmes largely were ineffective in leading to behaviour change. In addition, many of the perceived underlying factors of ill-health, such as poor water and sanitation (and other social determinants of health), were outside of their control as individuals even where awareness was sufficient. Treatment, therefore, was considered important to address these issues.

‘[Community members] are just ignoring the knowledge [on malaria] that they have and there is nothing that can change them. So…it is better we don’t give education but we prevent them from dying’ (G5)

Treatment as HIV prevention, investment in future generations and to address NCD fatalities

Treatment was considered especially important when it came to HIV/AIDS and TB and NCDs. For these issues, the treatment options required significantly greater investments compared to education and prevention, but many of the groups traded off prevention and/or education for treatment. The reasons for allocating resources to treatment for HIV/AIDS included that it contributed to prevention by reducing the risk of transmitting HIV. It was also viewed by some participants as investing in future generations and supporting those who may have been infected during the perinatal period. There were also concerns around drug stock-outs and HIV treatment adherence, and an investment in treatment was viewed as a way to address these issues.

‘I have chosen treatment for HIV/AIDS because if we can adhere to treatment, HIV cannot continue to spread and the future generation can be HIV free.’ (G7)

In relation to NCD chronic medication treatment, many of the groups expressed concerns about NCDs being serious and fatal without treatment. There were specific mentions of type 2 diabetes and hypertension as silent killers and treatment was viewed as a means to prevent these fatalities.

‘…There are diseases that kill people instantly…the government needs to put a lot of money on the chronic diseases like high blood pressure… sugar diabetes etc. because their lives are at stake and if they miss taking their treatment…they are gone.’ (G5)

Education for reproductive health, HIV/AIDS and violence against women and children

Despite the view of participants that existing health education did not lead to desired changes, some groups considered that it had a role to play. The issues that garnered the most allocation for education were reproductive health, HIV/AIDS and violence against women (specifically rape) and children. All these topics related to sexual practices and/or violence, some focused specifically on adolescent sexual practices, and health education was seen as important in this regard. There was an emphasis on community and family education as opposed to existing school-based programmes which were viewed as ineffective, and there was a need identified for open communication between parents and their children. Some of the groups also spoke to the need for more effective sexuality education at schools.

‘…educate the youth in the villages [with] parents also assisting them. Some teenagers get pregnant because they get engaged in sexual activities without the knowledge and information [they need] education on the effects of unprotected sex’. (G5)

Group 3 and Group 6, both mixed groups of men and women and with a mean age of 39 and 52, respectively, prioritized health education across health topics more than the other groups. Group 3 was the only group that did not select treatment for HIV/AIDs and TB, and instead chose to invest in comprehensive sexuality education. There was a deliberation about changing the selection to include treatment for HIV/AIDS and TB but the group maintained their position and noted that they would like to make a case for increasing the budget rather than forgoing sexuality education:

…. I think that education is the most important thing on HIV/AIDS because people will learn and know what will lead them into contracting HIV…I think it will be a good thing if we [keep our allocation as is] and we will go back to the government and ask for more money to budget for some of the things that we think are as important (G3)

Sexuality education and inequitable gender norms

Across the groups, inequitable gender norms were expressed, including views that women were responsible for the violence perpetrated against them. In two group discussions, there was a strong endorsement of rape myths, e.g., that young women would not be raped if they dressed appropriately. Sexuality education was viewed as a way to ensure that young women controlled their sexuality and were less provocative towards men. This perspective was prevalent among both males and female group members. It showed that while health education was viewed as the solution to some of the issues that the community faced, the nature of the education that was proposed would endorse unequal gender power relations.

…if as a mother, you can sit down with your daughters and teach them the good way to dress because they can be raped because of the way they are dressed (G6)

Group 7, which was the only entirely male did group did not consider violence against women and children an issue at all and did not select anything under this topic.

I did not choose this health service because as men we are known to be the abusers and we are not abusing anyone. It’s just that [young girls] love money too much and they can even lie and say that they have been raped meanwhile they only want money.(G7)

Education to improve treatment efficacy

Another reason why some groups selected education, particularly for issues such as HIV/AIDS and malaria, was to improve treatment efficacy. Delays in diagnoses were viewed as one of the reasons why treatment started late, often resulting in poorer outcomes. Education was viewed as important to address these issues—participants wanted better information about symptoms to ensure early help-seeking with a quicker diagnosis and initiation on treatment.

They can read the signs and know what to do. they can go to the clinic while there is time than to delay going to the clinic to get the treatment. So education is good so that people will be able to go to the clinic and get the treatment in case they have malaria. (G5)

HIV/AIDS and TB treatment and NCD treatment trade-offs

In addition to the trade-offs between primary prevention interventions and treatment interventions, among some of the groups, there were explicit trade-offs that took place between treatment for HIV/AIDS and TB and treatment for NCDs (which included two separate categories of chronic medication and treatment for complications).

Treatment for HIV/AIDS and TB required 16% of the budget and was selected by all groups except for one (Group 3). Treatment for NCDs required the highest percentage of the budget (25% for chronic meds and 9% for the treatment of complications) and was prioritized by all groups 4 of 7 selected chronic medication and the 3 that did not select chronic medication selected treatment for complications. These three groups traded off their NCD chronic medication investment for treatment for HIV/AIDS and TB and compromised by investing in treatment for NCD complications so that they were able to include a treatment option within this topic that was less costly.

Other groups (3 of 7) that selected both chronic medication for NCDs and treatment for HIV/AIDS (36% of the budget combined) traded off other interventions, specifically within primary prevention and education across categories.

The reasons given why groups prioritized HIV/AIDS and TB treatment over chronic medication for NCDs were based on age. HIV was perceived to be a disease that affects younger people while NCDs were viewed as more common among older people. Another factor was whether treatment was viewed as able to cure/control disease. TB was viewed as curable while NCDs were not. There was a perception among some of the groups that NCDs lead to death even where medication is available.

People who are living with HIV are able to live for a long with the treatment…and as for sugar diabetes, they don’t live for a long time even when they are taking the treatment. Once you have been diagnosed with sugar diabetes, you will die; there is no other way (G4)

One group (Group 4) debated at length selecting a chronic medication for NCDs, but later on, when discussing HIV/AIDS treatment made a strong case for removing the amount allocated to chronic medication for NCDs and giving it to treatment for HIV/AIDS.

I want treatment [for HIV/AIDS]. I understand that we can take our money from other areas because we are still budgeting…Why don’t we take the money that we have put on treatment for lifestyle diseases and put it on the treatment for HIV/AIDS and TB. (G4)

The group finally unanimously agreed on reallocation of funds. Their compromise was to allocate a percentage of their budget to treatment for complications under NCDs, which included amputations, treatment for strokes and chemotherapy.

Healthcare access trade-offs

Access to health care was considered important by all groups and was cross cutting. Access issues were predominantly discussed in relation to improving treatment interventions but were also considered important for family planning and antenatal care. Trade-offs primarily took place between the different categories under access as opposed to trading-off between access and other health issues. The top three priority issues included increasing the number of mobile clinics (selected by 6 of the 7 groups), longer operating hours at clinics (4 of 7), and improving nurse attitudes (3 of 7). Only one group selected increasing the number of nurses and pharmacists in clinics, and none of the groups invested in making chronic medications available at community centres.

Mobile clinics and longer hours to improve adherence to medication and healthcare access

Mobile clinics and clinics operational for longer hours were prioritized to improve adherence to chronic medication and ARVs, and to increase healthcare access for the elderly and disabled, especially in villages without clinics. Extended opening hours would overcome the challenges of individuals requiring emergency treatment after hours, which were compounded by limited household income which affected access to transport.

The number of mobile clinics [should] be increased because some families are…unable to pay the taxis to travel to the clinic. Some families are getting by through the social grants money and it is not enough. …It is a challenge if there is a member of that household that is ill and they are living under poverty, how can they travel to the clinic. (G3)

if there were clinics… and they were operating for 24 hours, at least [women] will go there to give birth …some lose their babies because they have to travel a long distance to the hospital. (G5)

There were some discussions about the need for primary health care clinics in every village, even though this was not an option on the CHAT board. One group (Group 5) discussed investing in additional clinics instead of mobile clinics. However, there was recognition that this would likely be unaffordable for the entire community of Bushbuckridge and so mobile clinics were viewed as an interim solution.

Nurse attitudes as a barrier to healthcare access

Nurse attitudes were perceived as barriers to HIV testing and treatment, which was related to stigma, and to family planning and ANC services, especially for young women and teenagers.

The nurses have their own gestures that they use to show each other that you are HIV positive. And for some people who are HIV positive… they have the fear that the people working in their local clinic will disclose their health status to other people. (G1)

Group 4 which was a younger Group (20–28 years) with 10 women and only one male were especially concerned about the nurse attitudes:

These nurses don’t know what they want us to do because if we go to the clinic for contraceptives, they tell us that we are still young for someone who is sexual active…And again if we go to the clinic for ante-natal care, they also tell us that we have fallen pregnant at an early age because we were not using the contraceptives; what do they want us to do exactly?(G4)

Improving nurse attitudes and increasing the number of mobile clinics did not require a substantial amount of the budget (both 3%), but participants commented that they were willing to spend even more on these areas.

Discussion

The implementation of the CHAT SA tool in a rural setting in South Africa demonstrates that the groups were able to engage with various trade-offs required when developing a health services package within the context of resource constraints and reach a consensus on priorities. There is evidence on expert opinions for priorities for UHC in South Africa, and limited work on community views on health system challenges to improve public sector services under NHI (Honda et al., 2015; Mathew and Mash, 2019). This is the first time a deliberative approach was used to consider the views of the public with regard to the design of a health services package under UHC and in the context of a constrained budget. The priorities and the justification behind the choices that emerged from the CHAT exercise reflect some of the social values of the community and could be useful in informing decisions about health services as South Africa moves towards UHC.

A predominant theme across groups was the medicalization of healthcare and prioritization of curative services over primary prevention options, and the need to invest in improvements of the former. This was linked to perceived inefficiencies in existing health programmes and services, which result in treatment delays and are compounded by barriers to access. The community priorities were also related to perceptions about disease progression. In relation to HIV/AIDS, there was an understanding and appreciation for the ability to continue to live a long life by adhering to ART, yet with regard to NCDs, there was a belief that they shortened people’s lifespan even with treatment. The misconceptions related to NCDs may be influenced by the fact that people with HIV/AIDS usually present at a much younger age than those with NCDs. These misconceptions are also likely influenced by delays in screening and diagnoses of NCDs which ultimately results in limitations regarding treatment efficacy in South Africa, as well as a historical country-level prioritization of HIV/AIDS testing and treatment with limited resources having been available for other illnesses like NCDs (Schutte, 2019; Madela et al., 2020). This speaks to the need to tackle health system failures not only to improve health outcomes but also to encourage a deeper understanding of disease and illness, which in turn is related to the shortcoming of current awareness programmes. This also supports the more recent approach of investing in NCD prevention and treatment.

None of the groups focused solely on health education and prevention services. Existing health education programmes were viewed as often being ineffective in leading to behaviour change. The finding indicates either a disjuncture between current prioritization and community need or that implementation of existing policies and programmes are ineffective at the community level. Where primary prevention was considered important it related predominantly to community-based sexuality education or was directly related to improving treatment efficacy and investing in children as the future generation through interventions like immunizations. This demonstrates that more of an emphasis should be placed on community-level programmes and that children are valued as important members of the community to preserve the future.

Access issues were the backbone of the deliberations and intertwined specifically with treatment efficacy considerations. Because the groups viewed health as being medicalized, access to treatment was important in order to improve these outcomes. Access issues were also linked to poverty especially with regard to transport costs to distant clinics and investing in mobile clinics was viewed as a way to address these challenges. None of the groups selected chronic medication availability at community health centres which is a current policy initiative in the country. South Africa is committed to more effective dispensing of chronic medication (including ARVs) often through community health centres in rural areas (Health Systems Trust, 2016). While the need for improved chronic medication provision is clear, the barriers to this type of service and the preference for allocation of resources toward other interventions like mobile clinics may have been overlooked by policymakers in the absence of meaningful public engagement. Some of these barriers may be due to specific issues that were raised by the groups which included stigma and discrimination that still prevails in relation to HIV/AIDS and the need for confidentiality around HIV testing and treatment (Pantelic et al., 2020). This may be easier to ensure through alternative collection points like mobile clinics, as opposed to community health centres.

While violence against women and children was recognized as an issue by most of the groups, gender attitudes of all groups, especially the all-male group, were untransformed with blame placed on women. This was specifically stated in relation to the manner in which women or young girls dress, which is often used as a justification of violence against women and perpetuates hegemonic masculinity (Smith et al., 2015). This prevailing view among the groups demonstrates that the findings of this study, as well as any public engagement process should be interpreted within a broader Human Rights lens which values ethical considerations like equity.

The groups also did not invest in palliative care but broader ethical consideration like the ease of suffering or dying with dignity would be important to consider for any context. This speaks to the need for priority-setting processes to incorporate public engagement with multiple community groups and to be governed by broader ethical consideration that may not emerge within the social values of the groups (Clark and Weale, 2012). Ethical frameworks for priority-setting alongside public engagement can be helpful in this regard.

South Africa is committed to public engagement in priority-setting for health, yet the views of communities are in reality not considered in policy and programme development which largely involves top down decision-making (Gilson and Daire, 2011). The implementation of the policies in turn is not evaluated in terms of responding to community needs. This perpetuates a cycle of policies and programmes that are often inappropriate and ineffective (Maphumulo and Bhengu, 2019). While South Africa’s National Parliamentary process includes public consultations and while there are mechanisms in place at the local level, like the Community Health Committees, these engagements have not been deliberative nor about what trade-offs the public would be willing to make within a constrained budget. The implementation of CHAT in a rural setting in South Africa demonstrates that deliberative engagement methods can be successful in helping communities balance trade-offs and in eliciting social values around health priorities. This is similar to findings from previous CHAT exercises which demonstrated that decisions were made that were not only based on personal preferences but on societal priorities and values (Dror et al., 2007; Danis et al., 2010; Schindler et al., 2018).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The way in which we designed the CHAT board meant that the intervention categories were independent of one another, e.g., treatment for complications under NCDs could be selected without selecting chronic medication which in turn did not allow for the cascading impact on the cost which would be a consideration in a real-life context. Our design was intentional in order to allow participants to prioritize between primary prevention and curative services but in doing so the true cost of the one option without selecting the other is not reflected. Other CHAT exercises have provided levels contingent on others, but it is still difficult to reflect changes in costs of some interventions after the selection of others. Any future virtual design of CHAT may benefit from including a feature that allows for the cost of interventions to be modified in real time as other interventions are selected. In addition, choices were constrained by prior selection of what is on the CHAT board. Our participatory methodology for modifying the CHAT board resulted in some topics/issues being excluded, e.g., mental health care, despite the fact that this is widely recommended. On the other hand, the benefit of CHAT is that there is room for deliberation so that expression of group preferences is not totally dictated by what is offered on the board, this was evident as the groups discussed the need for permanent primary health care clinics even though this was not an option on the board.

An additional limitation is that although the costs of interventions are captured by the sticker hole allocation on the CHAT board, cost effectiveness information is not depicted. The deliberations that result are therefore influenced by the costs of the interventions and the views of participants but not cost effectiveness data. Prevalence information is also not provided but the topics and interventions that were included in the CHAT board were reflective of the disease burden in Bushbuckridge.

A further limitation is that CHAT is a time-intensive exercise and in order for it to influence priority-setting it would need to be implemented with additional ‘publics’ or supplemented with a broader engagement strategy that makes use of mechanisms like online democratic forums. This speaks to the need to develop engagement tools that are a key component of priority-setting institutions and can impact decision-making in a timely fashion.

Another limitation is related to reconciling differences among the groups. While there were some overarching themes and clear convergence of priorities across groups there were also some divergent views, e.g., the importance of sexuality education. It is not clear if these divergent views represent entrenched differences in social values, personal experiences or conceptualization of issues but this could be further explored with additional CHAT exercises.

Conclusion

As South Africa moves towards UHC, economic evaluations will be important in guiding difficult coverage decisions. However, broader social values will need to be considered in order to ensure these decisions are appropriate. In addition, any priority-setting process for health would benefit from meaningful public engagement to enhance its legitimacy. While some criticism of public engagement focus on the complexity of resource allocation decisions and the inability of the lay public to grapple with such decisions (Carpini et al., 2004) the implementation of CHAT SA demonstrates that communities can appreciate the concept of trade-offs within the context of limited resources and that there is value in engaging with communities for priority-setting for health. The findings from such deliberations, alongside other cost effectiveness evidence and broader ethical considerations has the potential to inform decision-making at the different levels with regard to health policy design and implementation. This ultimately can lead to improved priority-setting processes so that health outcomes are more successful.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Health Policy and Planning online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Audrey Khosa for coordinating the project in Bushbuckridge and Meriam Maritze for facilitating the group deliberations.

Funding

This work was supported by The South African Medical Research Council [SAMRC-RFA-EMU-02-2018].

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa [Clearance certificate number M161009].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Appendix A CHAT facilitator Script

CHAT SA

‘Choosing Healthplans All Together for South Africa’

FACILITATOR SCRIPT

Note to Facilitator: Read the regular print out loud. The italicized print in parentheses provides the facilitator directions that are not meant to be read aloud

Introduction

(Prepare the room as follows: For each player lay out a packet containing two paper CHAT boards, two sets of stickers, an information manual and a pre- and post-exercise survey. Each of these packets and the material in them should be labelled with an assigned study number. Place the large CHAT board in the middle (or in sight of all participants) and have large stickers for use on the large board. If the session will be tape recorded, have the tape in the recorder ready to be turned on)

STUDY TITLE: Engaging the public in priority setting for health in a rural setting in South Africa

Welcome! I’m _______________ and these are my co-fieldworkers, _________________. Today you are taking part in an exercise called ‘CHAT.’ CHAT stands for Choosing Health-plans All Together. We are here to help you decide what health services are most important to you

You have each received a participant information sheet from the fieldworkers when they invited you to participate in the study and you have signed a consent form to participate as well as a form that consents to the audio and video recording of the exercise today. I would like to remind you that you will not be expected to share your name and it will not be connected with the recording or the transcript. You will not be identified by name in any of the reports or publications of this study or its results. The information that is collected will be used for educational and scientific purposes.

Taking part in this study is completely your choice. You have already agreed to participate but you can stop participating in the study at any time if you want. By agreeing to participate you must feel comfortable with the exercise being audiotaped and videotaped and if you are not comfortable with this you can choose not to participate without anything negative happening.

The information we collect from this exercise will be very helpful to us in understanding which health services are important to you. This project is an opportunity for you to voice your views about health services and we will try and feedback these views to the government who decides which services to provide. Thank you for taking the time to share this experience with us. We will answer all your questions as we go along. We hope you have fun.

You have each been given a packet of CHAT materials. Please note that we will collect this material at the end of the session, to use it with other groups. I will read these materials to you. We will know your choices later, when we have replies of many groups, by referring only to the study and participants number on these papers (point out the number on the papers). This way we will protect your privacy. We ask all of you to also keep private information you hear from each other during the game –private; please do not repeat what you heard after you leave this session.

OK, we will begin by filling out the first questionnaire. I will read each question and you can select the answer that fits best for you.

(READ each question and all the answers and make sure participants feel comfortable and understand how to answer each question.)

Thank you for answering the questionnaire.

Now as we begin the CHAT exercise, let me tell you a bit about the health service package.

Sometimes people in your household become ill. When this happens, you try to help them as best you can. You take them to the clinic to get medicine. If you do not go to the clinic or get medicine your family member may be ill longer. If the illness gets terribly bad, your family member must go to the hospital. Sometimes people need to take medicine for their whole life, like if they have a chronic lifestyle disease like diabetes. The government tries to provide health services for everybody to make sure that those people who are sick are able to get the care and support that they need. The government also tries to stop people from getting sick in the first place by running things like education campaigns. All these things cost the government money and, just like in every country in the world, there sometimes isn’t enough money to pay for all the services that we need. The government needs to decide which health services are the most important and where they should spend their money. It’s the same as when you go to the shops. You have some money at the end of the month and you go to the shops to buy food for your family. You don’t have enough money to buy everything so you need to decide between milk, cereal, tinned food, meat etc. These are the choices that you make. In the same way, the government has to choose which health services to provide.

So in this exercise we want you to think about which health services you would like to see included in a health package. For example, it could be education and information for HIV/AIDS and TB or prevention and screening for lifestyle diseases, or you may think things like clinics being open for longer hours is important. You will make choices using the stickers that are available to you. The stickers are the money that is available and you will only be able to select as many options as the stickers can cover. We hope this exercise will help you to understand that not everything can be provided and will help you to choose the things that are most important.

As we begin, let me give you some instructions:

Purpose

The purpose of CHAT is to help people to choose the components of a health service package that they prefer and think are most important.

Taking part in CHAT

There are three Rounds in this CHAT exercise.

In the First Round, each of you will make a health package that you think is best for you and your family.

In the Second Round you will all work together to make a health package for a whole community (all people living in Bushbuckridge).

In the Third Round you will again make a health package for you and your family, using all you learned as you took part in the second round.

Let us make sure that we treat everyone with respect during this exercise and we give other people a chance to talk, please do not interrupt others or have your won conversations on the side

FIRST ROUND

Step 1. You determine your ideal Health Service Package for you and your family

Let’s start with the first Round. Does everyone have a CHAT Exercise Board, CHAT Booklet, and 35 stickers? (Hold up CHAT Game Board, CHAT Bookletand Stickers.) Your CHAT Board has 7 health service areas and in each of these areas there are different options to choose from, for example- education and information or prevention and screening or treatment. I will show you the picture, the colour, and the name of each of the service areas (Hold up the large CHAT Board and point to icon and name of each service area while reading the names out loud.) (Hold up CHAT Booklet.) Your CHAT Booklet explains these different services and the different options. (Open the CHAT booklet, point to the icon for each health service area and read the description of each option). Before you decide which services to pick from the board you must make sure you have read the booklet explaining the different components of the services. During the game if anyone needs help looking for things in the booklet please ask and we will help

(Hold up Stickers.) You make your choices by pasting stickers on the CHAT Board. This is why we give you 35 Stickers to paste. You can only choose services so long as you have stickers, so the game is to choose the health services you want most with the number of stickers you have.

For each health service you might choose to take it or leave it. Some services do not cost very much and only need 1 sticker while others cost more and need more sticker (Demonstrate the different options on theCHAT Board.).

Let’s begin Round One. Remember that you are making a package just for you and your family in round 1- Put your Stickers on your CHAT Board selections. Make the package you like using all the Stickers you have. You can decide to change your mind and move around your stickers at any point during round 1- Choose by yourself. Work on your own but if you need any help or advice using the board and the booklet please ask and we will be happy to help. You can take about 15 min for this step. Go ahead; begin.

( PAUSE. Allow players time to work. Be available to answer questions. Let players know when there are only a few minutes left. After about 30 min say)

Step 2. Test Your Health Package

Okay. Now that you finished making your choices you can’t change them anymore in this round- et’s test your package. You can see the results of the choices you picked by the CHAT health event cards which the fieldworkers will read. Each of the cards relates to one of the health services on the board. On the back of the card there is a medical problem you might face. The fieldworkers will read the cards. Some Event Cards are about men or women or children.

After we read the event card, please share your thoughts about how the health package you have designed in round 1 would help the medical problem or not and would you change anything about your package As you listen to the different medical stories on each card, you’ll get a better and better idea of what is important and what you want the health package to include.

Now the fieldworkers will read the cards

(PAUSE. Probe with additional questions such as: Did you package work the way you expected it to work? Would you consider changing your priorities? making different choices in the future? After completion of Round One, go to Round Two)

Second round

We’ve completed the First Round and will now move on to the Second Round. Now we’ll ‘Choose a Health package All Together’ as one big group. Now please think about a package of health services that is for everyone in the community, not just for your family. To do this, we’ll use this Big CHAT Board (Point to Board).

We’ll each take turns saying what we prefer, and try to convince the group to agree. We’ll go around the table asking each person to choose an option within one of the health service areas. We will ask you to tell us why you make this choice, and allow others to comment. If others agree, I’ll place stickers, on the Big CHAT Board. If someone disagrees with a suggestion, please raise your hand and tell us why. We will decide together whether it is a good idea to add the option and we will vote whether to include it. Please don’t be upset if what you want does not get included in the board- remember the way we decide is by majority vote-

(PAUSE for questions.)

Let’s begin making our recommendations. (Pick a person to start.), Let’s begin with you. What health service area and which option would you like to select? Why do you select this? (important to remember to ask WHY the participants select the options that they do and for fieldworkers to note)

(PAUSE. After completion of the second Round, go to the Third Round and say:)

Third ROUND

Now let’s move to the Third and last Round.

In this Round, each of you will repeat what you did in Round One: you’ll make a choice on your own to create a package for you and your family again, also think about the future and everything you learned in the group round-ith all that you’ve heard and thought about playing this game, take about 10 min to make the selection of services, using your 35 tickers and your CHAT Board. Once again, work on your own but please ask for help if you need it. Begin.

(PAUSE. Allow players time to work. After about 5 min say:)

If you’re finished, please wait for the Post-exercise questionnaire.

Now, let’s complete the questionnaire. I will read each question and you can check the answer that fits best for you.

(READ each question and all the answers and make sure participants feel comfortable and understand how to answer each question.)

Thank you for participating in the CHAT exercise. We hope you enjoyed it.

Post-exercise debriefing if time allows

(To make this a valuable debriefing, be prepared to probe the debriefing questions with follow up questions such as: Why? Why not? What do you mean? How do others feel about this?)

Now that you’ve participated in the CHAT exercise, we’d like to know

What did you think of it?

What about the exercise did you enjoy?

What did you not enjoy about the exercise?

Do you remember at the beginning, we said the purpose of CHAT was to help people to choose the components of a health service package that they prefer and think are most important. Do you think this exercise succeeded? Did it help you to make these choices?

What do you think about the final package made by the group? (Would you want this same package for your family?)

(As Facilitator, take cues from statements of Participants.)

(PAUSE. Allow time for general critique of the exercise and discussion of the exercise’s success in achieving its purpose. Then say:)

We hope you enjoyed the CHAT exercise. Thank You very much for joining in!'

Contributor Information

Aviva Tugendhaft, SAMRC/Wits Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science- PRICELESS, School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Karen Hofman, SAMRC/Wits Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science- PRICELESS, School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Marion Danis, Department of Bioethics, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Kathleen Kahn, MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit -Agincourt, School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Agnes Erzse, SAMRC/Wits Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science- PRICELESS, School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Rhian Twine, MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit -Agincourt, School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Marthe Gold, New York Academy of Medicine, New York City, NY, USA.

Nicola Christofides, School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

References

- Abelson J, Blacksher E, Li K, Boesveld S, Goold S.. 2013. Public deliberation in health policy and bioethics: mapping an emerging, interdisciplinary field. Journal of Public Deliberation 9. doi: 10.16997/jdd.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J. et al. 2003. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Social Science & Medicine 57: 239–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderman KB, Hipgrave D, Jimenez-Soto E.. 2013. Public engagement in health priority setting in low- and middle-income countries: current trends and considerations for policy. PLOS Medicine 10: e1001495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddy J, Vergez C.. 2001. Citizens as Partners: Information, Consultation and Public Participation in Policy-Making. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Carman KL, Heeringa JW, Heil SKR. et al. 2013. The Use of Public Deliberation in Eliciting Public Input: Findings from a Literature Review. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Effective Healthcare Program. [Google Scholar]

- Carpini MXD, Cook FL, Jacobs LR.. 2004. Public deliberation, discursive participation, and citizen engagement: a review of the empirical literature. Annual Review of Political Science 7: 315–44. [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Weale A.. 2012. Social values in health priority setting: a conceptual framework. Journal of Health Organization and Management 26: 293–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Competition Commission. 2019. Health Market Enquiry: Final Findings and Recommendations Report. https://www.hfassociation.co.za/images/docs/Health-Market-Inquiry-Report.pdf, accessed 24 September 2020.

- Danis M, Kotwani N, Garrett J. et al. 2010. Priorities of low-income urban residents for interventions to address the socio-economic determinants of health. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 21: 1318–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. 2015. White Paper on National Health Insurance. Governemnt Gazette No 39506. Department of Health Republic of South Africa (ed). Pretoria, South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201512/39506gon1230.pdf, accessed 14 July 2020

- Dror DM, Koren R, Ost A. et al. 2007. Health insurance benefit packages prioritized by low-income clients in India: three criteria to estimate effectiveness of choice. Social Science & Medicine 64: 884–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edoka IP, Stacey N.. 2020. Estimating a cost-effectiveness threshold for health care decision-making in South Africa. Health Policy and Planning 35: 546–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin D, Dixon J.. 2004. Public involvement in health care. BMJ 328: 159–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L, Daire J.. 2011. Leadership and Governance within the South African Health System In Padarath A, English R, South African Health Review 2011. Durban: Health Systems Trust. http://www.hst.org.za/publications/south-african-health-review-2011, accessed 24 August 2020

- Goold SD, Biddle AK, Klipp G, Hall CN, Danis M.. 2005. Choosing healthplans all together: a deliberative exercise for allocating limited health care resources. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 30: 563–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of South Africa. 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa.http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/SAConstitution-web-eng.pdf, accessed 16 July 2020.

- Government of the Republic of South Africa. 2018. Presidential Health Summit 2018 Report.https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201902/presidential-health-summit-report.pdf, accessed 6 August 2020.

- Health Systems Trust. 2016. CCMDD: A Vehicle Towards Universal Access to Anti Retrovirals and Other Chronic Medicines in South Africa.https://www.hst.org.za/hstconference/hstconference2016/Presentations/hst_conf_ccmdd_h_zeeman_28_04_2016.pdf, accessed 5 September 2020

- Honda A, Ryan M, van Niekerk R, McIntyre D.. 2015. Improving the public health sector in South Africa: eliciting public preferences using a discrete choice experiment. Health Policy and Planning 30: 600–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn K, Collinson MA, Gomez-Olive FX. et al. 2012. Profile: Agincourt health and socio-demographic surveillance system. International Journal of Epidemiology 41: 988–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madela S, James S, Sewpaul R, Madela S, Reddy P.. 2020. Early detection, care and control of hypertension and diabetes in South Africa: a community-based approach. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 12: e1–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maphumulo WT, Bhengu BR.. 2019. Challenges of quality improvement in the healthcare of South Africa post-apartheid: a critical review. Curationis 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew S, Mash R.. 2019. Exploring the beliefs and attitudes of private general practitioners towards national health insurance in Cape Town. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 17: e1–e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Department of Health. 2003. National Health Act 61 of 2003. National Department of Health (ed). Republic of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/documents/national-health-act, accessed 16 July 2020

- NCOP’. 2019. Public Participation Model.https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Pages/2019/august/19-08-2019_ncop_planning_session/docs/Parliament_Public_Participation_Model.pdf, accessed 10 September 2020.

- Oladeinde O, Mabetha D, Twine R, et al. 2020. Building cooperative learning to address alcohol and other drug abuse in Mpumalanga, South Africa: a participatory action research process. Global Health Action 13: 1726722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padarath A, Friedman I.. 2008. The Status of Clinic Committees in Primary Level Public Health Sector Facilities in South Africa. Durban: Health Systems Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Pantelic M, Casale M, Cluver L, Toska E, Moshabela M.. 2020. Multiple forms of discrimination and internalized stigma compromise retention in HIV care among adolescents: findings from a South African cohort. Journal of the International AIDS Society 23: e25488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler M, Danis M, Goold SD, Hurst SA.. 2018. Solidarity and cost management: Swiss citizens' reasons for priorities regarding health insurance coverage. Health Expectations 21: 858–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte A.2019. Urgency for South Africa to prioritise cardiovascular disease management. The Lancet Global Health 7: E177–E78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuffham PA, Ratcliffe J, Kendall E. et al. 2014. Engaging the public in healthcare decision-making: quantifying preferences for healthcare through citizens' juries. BMJ Open 4: e005437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RM, Parrott DJ, Swartout KM, Tharp AT.. 2015. Deconstructing hegemonic masculinity: the roles of antifemininity, subordination to women, and sexual dominance in men's perpetration of sexual aggression. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 16: 160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S, Abelson J.. 2012. Why and when should we use public deliberation? Hastings Center Report 42: 17–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South African Legislative Sector. 2013. Public Participation Framework for the South African Legislative Sector. http://sals.gov.za/docs/pubs/ppf.pdf, accessed 6 July 2020.

- Terwindt F, Rajan D, Soucat A.. 2016. Chapter 4: Priority setting for national health policies, strategies and plans. In Schmets G, Rajan D, Kadandale S (eds). Strategizing National Health in the 21st Century: A Handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Tugendhaft A, Danis M, Christofides N. et al. 2020. CHAT SA: modification of a public engagement tool for priority setting for a South African rural context. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. In press. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twine R, Kahn K, Scholtz A, Norris SA.. 2016. Involvement of stakeholders in determining health priorities of adolescents in rural South Africa. Global Health Action 9:29162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weale A, Kieslich K, Littlejohns P. et al. 2016. Introduction: priority setting, equitable access and public involvement in health care. Journal of Health Organization and Management 30: 736–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. 2014. Making Fair Choices on the Path to Universal Health Coverage: Final Report of the WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage.http://www.who.int/choice/documents/making_fair_choices/en/, accessed 6 July 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.